Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Connor, J.D. - Sartre and Cinema-The Grammar of Commitment

Uploaded by

Omar RodriguezOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Connor, J.D. - Sartre and Cinema-The Grammar of Commitment

Uploaded by

Omar RodriguezCopyright:

Available Formats

MLN

1045

Sartre and Cinema: The Grammar of Commitment

J. D. Connor

I. Medium of Exchange Even before his release from prison camp at Baccarat, Jean-Paul Sartre was worried about money. At rst, there was a backlog of funds being held for him at Nouvelle Revue Franaise12,855 francs; I said: twelve thousand eight hundred fty-ve francs.1 Although that would be enough to hold him and Beauvoir for some time, Sartre had to face again the prospect of earning a living by teaching. Once back at the lyce, and in between prayers for Allied bombing raids that would at least interrupt his classes (QM 264), he adopted a twofold strategy. First, he determined to make a great deal of money as quickly as possible by writing screenplays for Path. Second, during the window of nancial opportunity this afforded him, he would ratchet up his own literary production, intensifying his self-exploitation through the use of amphetamines. In the summer of 1943, when he was nishing the rst draft of the screenplay for The Chips are Down (Les Jeux sont faits) he received a payment of FF37,500, with the promise of more to come. So there is a strong chance, he wrote Beauvoir. Truly well be able to say piss off to the alma mater (QM 256). Although The Chips are Down was accepted, it was not until In the Mesh (LEngrenage) (see gure 1) was also taken by Path that Sartre and Beauvoir were on easy street.2 Still, the strategy was largely successful, and in its wake, critics have ignored Sartres early work on the cinema, assuming it was little more than a way out of the academy. (The Freud Scenario, fteen years away,

MLN 116 (2001): 10451068 2001 by The Johns Hopkins University Press

1046

J. D. CONNOR

has been an exception.) The strictly pecuniary motives behind Sartres rst screenplays combined with his later disavowals to erase them from the critical radar. He stressed that The Chips are Down was not existentialist, and he ordered his name removed from the credits for The Proud Ones (Les Orgueilleux) (as he later but more publicly did on Freud ). As for In the Mesh, it was never produced, and the publication of its screenplay in 1948, at the height of the Sartre boom, went largely unnoticed. All in all, as his bio-bibliographers Contat and Rybalka put it, His relationships with the movies have been . . . unfortunate because almost all the adaptations of his works

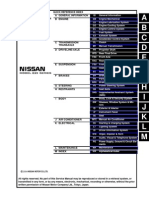

Figure 1: Leonard Rosomans cover for Sartres In the Mesh, rst British edition, Andrew Dakers, 1954.

MLN

1047

or original scripts have been, according to an expression which is no doubt excessive but is Sartres own, lamentable failures.3 The critical neglect notwithstanding, the mid-forties were a period when Sartres longheld affection for movieswe love the cinema he declared in his rst public lecture4joined his novels, philosophy, political essays and work for the legitimate theater in a multimedia assault. And like other elements of the Sartre enterprise, he surrounded the screenplays with criticism, some journalism and repeated attempts at a theorization. I want to focus on that last aspect here, tracing out a notion of repetition or iteration that itself recurs in Sartres cinematic writing of the forties. What he makes of repetitiongrammatically, narratively, politicallyconstitutes, I argue, one of the places we can best understand the movement from ontology (Being and Nothingness, 1943) to cultural politics (What is Literature?, 1947). Sartres episodic writing for and about lm reveals a shift from attention to lm as a medium to its political-narrative possibilities and then to the production system behind it. The writing about lm, however, does more than merely shadow the overall path of Sartres concerns. In these avowedly extraneous efforts Sartre accomplishes the transitions between the major zones of his theoretical concerns and formulates what might have been a decisive account of the relationship between the artist and the work had he been able to take it to heart. Finally, this complex negotiation with lm sheds fresh light on the lingering assumption that Sartre avoids the problem of language in order to concentrate on sociopolitical action. From the very rst commentaries on Sartres work, he has been chastised for failing to accord language its proper importance. As Iris Murdoch put it in what is still the most serious attempt to relate Sartres philosophy to the British analysts of the same period, his philosophical consciousness stop[s] short of a critical awareness of language.5 (To Murdochs credit, the point of her study is to dig out and explicate the romantic rationalism of what we might call Sartres philosophical unconsciousness.) Sartre was accused of a similar avoidance in the heated debate surrounding Jean Paulhans discourse on language, Les Fleurs de tarbes. For Paulhan, Sartres subordination of the problem of language to ontology meant that he had never really begun to talk about language.6 What is striking about this criticism (Murdoch and Paulhan are joined by Blanchot, Merleau-Ponty, Jameson, LaCapra and others) is that it steadfastly avoids the one place where (the early) Sartre does talk about

1048

J. D. CONNOR

language in detail. In the chapter of Being and Nothingness entitled The Situation, Sartre describes the relationship between the given and the situationthe central relationship from which the freedom of the for-itself (pour-soi ) emergesthrough an explication of grammar. For Sartre, linguistics makes a determinist error when it assumes that grammar is a set of rules that bind speakers when they assemble words into sentences. People in considering speech frequently will take speech that is dead (i.e., already spoken) and infuse into it an impersonal life and force, afnities and repulsions, all of which have in fact been borrowed from the personal freedom of the for-itself which spoke.7 Sartres image for this fundamental error is cinematic:

A word can indeed seem to have a life of its own if one comes upon it in sentences of various epochs. This borrowed life resembles that of an object in a lm fantasy; for example, a knife which by itself starts slicing a pear. It is effected by the juxtaposition of instantaneities; it is cinematographic and is constituted in universal time. (BN 5156)

Just as a number of slightly different images, when ickering, can produce motion on a screen, so a series of word uses can play on a linguistic phi -phenomenon. But these living words are the products of a kind of stop-action animation; they are a lm fantasy. [W]ords appear to live when one projects a semantic or morphological lm (BN 516). Sartre imagines the linguist who supposes that words have a meaning independent of any intention as the audience of a lm, a semantic lm of his or her own projection. And just as an audience will dupe itself (be duped) into believing that a knife moves itself, or, on the contrary, that a persons existence is determined, so the linguist can be duped (by himself or herself) into thinking that a word means something or that a persons speech is governed by laws not of the speakers own making. Sartres subordination of language to ontologyPaulhan was not wrong thererequires that the speaker be the concrete foundation of his speech (BN 515). For that to be the case, Sartre replaces the linguists conception of sentences as assemblies of words with the idea of sentences as synthetic unities: [T]he word is not the concrete element of speech . . . ; the elementary structure of speech is the sentence. It is within the sentence, in fact, that the word can receive a real function as a designation; outside of the sentence the word is just a propositional function (BN 514, ellipses added). At the same time, Sartres shift from the living word to the living speaker does not invalidate linguistic discoveries. [W]e do not thereby suppress the

MLN

1049

necessary technical connections or the connections in fact which are articulated inside the sentence. Better yet, we found this necessity (BN 517). Speaking, which Sartre wants to understand as a free project of the for-itself, is a process that is literally autonomous. Thus it is within the free project of the sentence that the laws of speech are organized; it is by speaking that I make grammar. Freedom is the only possible foundation of the laws of language (BN 517). I make the laws of language when I speak; they do not constitute a limit on my freedom. Sartre goes on to trace the origin of the linguists error. Grammatical rules exist only in and through this sentence; they are incarnated by it. At the same time, the sentence is a scheme to assume this given (these laws of word order and dialectal pronunciation). Sentences, then, must be incarnated (spoken, written) in order to substantiate the speakers freedom. But the incarnating function of the sentence makes the sentence appear as a free invention of its own laws. That is, the speaker, as a kind of meaning-projector, disappears, and the sentence stands on its own, the product of certain rules of linguistic assembly. In the repetitions of these quasifreestanding sentences, the linguist sees a pattern.8 He or she juxtaposes the instantaneities and concludes that the given produces the sentence. Semantic lm. The importance of the linguists error in understanding Sartre is not simply that its elaboration constitutes Sartres most direct discussion of grammar but also that it provides an example of the structure of philosophical thinking that underlies the idea of bad faith. In his description of language becoming lm, becoming an aesthetic object for the linguist, Sartre provides an outline for the broader question of how it is that ones life can seem to be external to oneself; how one can lie to oneself. And in the fundamental image of the phi phenomenon, he nds an image that conserves the appearance of an object while it accounts for the disappearance of the intention behind it. A comparison with Paulhan is illustrative. For Paulhan, whose frame of reference is linguistic, the speaker who wants to make a new language (the terrorist) must attend more than ever to the language that already exists: No writer is more preoccupied with words than the one who is determined at every turn to get rid of them, to get away from them, or even to reinvent them (DG 85). For Sartre, whose frame is ontological, the person in bad faith must know the truth very exactly in order to conceal it more carefully (BN 49). For Paulhan, the bind is inescapable, a mystery, but Sartre must

1050

J. D. CONNOR

account for the seemingly unlikely durability of bad faith: A person can live in bad faith (BN 50). The difculty with the notion of bad faith stems from the total translucency of consciousness, namely, How then can the lie subsist if the duality which conditions it is suppressed? How can one lie to oneself?9 Sartre does not opt for the easy out of a dual consciousness, whether temporal or spatial that would at a pinch allow us to reestablish a semblance of duality: a liar and (then) a lie. The psychoanalytic recourse to a split consciousness substitutes for the notion of bad faith, the idea of a lie without a liar (BN 51), thus repeating the linguists error of making a language which speaks itself (BN 516). Instead of these hardened dualities, Sartre wants to preserve the tenuousness of the split between liar and lied-to, for that is the very essence of the phenomenon he is describing. If consciousness is translucent, lying to oneself becomes a slippery enterprise, an evanescent phenomenon which exists only in and through its own differentiation. At this point, the cinematic metaphor appears implicitly, as the description of the most usual (or stable) kind of illusion: [T]here is in fact an evanescence of bad faith, which, it is evident, vacillates continually between good faith and cynicism. Even though the existence of bad faith is very precarious, and though it belongs to the kind of psychic structures we might call metastable, it presents nonetheless an autonomous and durable form. . . . A person can live in bad faith (BN 50, ellipses added). It vacillates (oscille). Sartre will elsewhere call this a icker (vacillement ). It is both unstable and durable, a characterological lm. This durability hinges on a process of aestheticization, a sealing off or forgetting of the good-faith agency that is lying. Like the linguist who juxtaposes instantaneities to project the semantic lm, a person in bad faith juxtaposes the instantaneities of consciousness (BN 45, 70) in order to project a characterological lm. In this way, the perception about linguistics as a kind of self-illusion that depended on the ickering of the lm becomes a perception about character which, appropriately, depends on the ickering of consciousness for its played-ness. Thus in the famous description of the waiter in the caf who is playing at being a waiter in a caf, the selfaestheticization appears as the conversion of himself into a mechanism (projector) while the metastable character of his bad faith appears as the tenuous balancing of his tray: [H]e returns, trying to imitate in his walk the inexible stiffness of some kind of automaton while carrying his tray with the recklessness of a tight-rope-walker by

MLN

1051

putting it in a perpetually unstable, perpetually broken equilibrium which he perpetually re-establishes by a light movement of the arm and hand (BN 59). The image almost perfectly captures the complications of bad faith. The waiter is completely responsible (all the verbs are his: he returns, he tries to imitate, he puts the tray in dangerous positions); the tray is vacillating in such a way that one cannot establish a dualitynow the waiter upsets it; now the waiter sets it rightbecause its every movement is a perpetual reestablishment of equilibrium (and not duality). The scene as a whole is imagined as the natural outcome of a prior choice that denes the situation: how else could one carry the tray on a tight-rope? It is the last aspect that carries the aestheticizing force of bad faith, the sealing off and integrating of it, what Sartre will call the faith of bad faith. In the terms of the waiters performance, this faith consists of the way he applies himself to chaining his movements as if they were a mechanism, the one regulating the other (BN 59). If his movements are the ickers of bad faith, his application is the faith of bad faith. But that faith, as Sartre describes it, only replicates the metastability of bad faith at the level of the disposition. And in fact, it is the potential for bad faith that is, he says, the actual eruption of bad faith. For me to have represented it [the disposition to bad faith] to myself as bad faith would have been cynicism; to believe it sincerely would have been in good faith (BN 68). As a result, the oscillation sets up again, one order removed from the characterological lm of the waiters movements. It may seem that this creates a daisy chain of reections, a faith of faith of faith, etc., and logically it might be so; but ontologically, the addition of a single further order to the street theater of bad faith exhausts its ramications. The faith of bad faith sufces because at that level it is the mode whereby consciousness assumes its facticity, the waiter assumes his waiting. At the level of his actions, the waiter could choose to occupy a number of positions other than that of waiter (a waiter who quits, who drops his tray, who is unemployed, etc.), but at the level of the meaning of his actions, the waiters choicehis applicationis not unconstrained. This inapprehensible fact of my condition, this impalpable difference, which distinguishes this drama of realization from drama pure and simple is what causes the for-itself, while choosing the meaning of its situation and while constituting itself as the founding of itself in situation, not to choose its position. . . . Without facticity consciousness could choose its attachment to the world in the same way as the souls in Platos Republic

1052

J. D. CONNOR

choose their condition (BN 83, ellipses added).10 The second order sufces, in other words, because the waiters attitude completely supplants the other possibilities of heeding the call of facticity. That is to say, facticity makes affectin Heidegger, the disclosedness of the world through ones moodparamount. The condemnation to freedom called facticity makes a necessity of choice and an option of affect: Whether in fury, pride, shame, disheartened refusal or joyous demand, it is necessary for me to choose to be what I am (BN 529). Put still another way, where an affect about an action is a change of order, an affect about an affect is not. It is still an affect. Sartres formulation here emphasizes the counterintuition that ones feelings, usually understood as reactions to a situation outside oneself, are chosen, or, more exactly, are the ways that one has chosen to be what one is. He puts it in this way, I think, because (as Heidegger discovered) the constancy of affect, or of mood, provides a way of cementing the necessity of choosing (of being open to the world); it answers the question, what is something I do all the time that can be like choosing all the time?11 Compelling a solution as this is, though, it raises the secondary problem of its aestheticization. Facticity, according to Sartre, is what separates the drama of realization from drama as such. But if one must have affects, how is one to know the difference between the world of free will and a world of determination?12 That of course assumes that there are affects in a world of determination, and it is this assumption that is the subject of Sartres rst screenplay for Path, The Chips are Down. II. Affects and Masses Sartre characterized The Chips are Down as bathed in determinism.13 At the same time, though, it is a screenplay bathed in affect. It tells the story of Eve and Pierre, she the wife of the chief of military police, he the leader of a group of conspirators. She is poisoned; he is shot by an informer. In a limbo world without passion that exists unseen and superimposed upon the city, they fall in love, and because of this exceptional occurrence, they are given a second chance at life. Thus far, the story is simply a more serious variation on the Stairway to Heaven -style post-war resurrection tale. But during their second chances, Pierre resolves to warn the conspirators (who have expelled him for his association with Eve) that they are being set up. He calls Eve to tell her and she protests. Simultaneously the informer res at Pierre, and Eve, still at the other end of the phone, collapses [c]omme

MLN

1053

frappe par les balles.14 They meet again in the limbo-afterlife, but have no feeling for each other, and part. As a solution to the determinist problem, The Chips are Down has the characteristic existential ambiguity. On the one hand, the second chance appears worthless since the outcome is the same. Things appear determined, so much so that the love that Eve and Pierre share is meaningless once they have died again. No transcendence is available. On the other hand, the second chance appears to conrm that things are not determined. In choosing as they do, Eve and Pierre simply box themselves in again. The motivated explanations for their second deaths make their rst deaths explicable not as outside forces acting upon them but as the product of a set of choices we simply did not see. These alternatives are encapsulated in the two deaths: the rst appears determined, the second chosen. Reconciling them is a matter of choosing between them, between the poles of the determinist problem, and that choice appears to be one of mere affect. And it is affect that gives Sartre his out. If one cannot decide between explanations in terms of behaviordo they or dont they choose?one can decide in terms of affect. Those who are alive have affects. This is such an axiomatic principle that its converse is felt to be a moral imperative for the death-administration: if you have affects (fall in love), you should be alive. (If you are incapable of having affects, you are determined.) The existence of affects is supposed to constitute sufcient evidence for choice; we know Eve and Pierre choose themselves in their situations because they have a set of feelings about that choice. To leave the explanation there, though, is impossible. The determination of the events in the lives of Eve and Pierre is inescapable. They have a determined character because they are characters. They are the drama as such of the drama of realization. Just as I make grammar for my listener when I speak, so Sartre makes destiny for his characters when they are written. It is impossible for the characters in Sartres screenplay to exercise free will because his decision to write such a story belies their freedom. Their determination is thus a gure for their literary status, and that determination is then regured in the character of the informer, Lucien Derjeu, a man who is the game himself. (The German article can be explained by his association with frenchied German things like the military police or the transom, a petit vasistas, through which he shoots Pierre [138].) The informer, who passes from transmitter to assassin, res rageusement (138). This adverbial affect of the informer-technician

1054

J. D. CONNOR

gures the affect of the writer. The denial of choice to the deathadministration is the converse. In bringing Eve and Pierre back to life, Sartre-God (although no God is seen, only heard) denies his agency by claiming that it is the characters affects that impose the imperative on him. At the end of the screenplay, then, it is the writerinformers passion that facilitates the end of the love affair by reclaiming the affect, the guarantee of free will, that was his all along. The determinist bath that cleansed The Chips are Down of affect substitutes one kind of entailment (they are characters; they are determined) for the more usual kind (they are people; they are free). Whether this was a defeat for Sartres theory, a conrmation of it, or, as he described it, a bit of fun, he was still preoccupied with the notion of how one could represent freedom on the screen. He takes up that problem, again indirectly, in his brief manifesto-ish piece, A Film for the Post-War, which appeared in Les Lettres franaises while The Chips are Down was still in preproduction. The lm industry has inherited a set of constraints from Vichy, Sartre says, which banned representations of collectivities. Milieux are not depicted; crowds are rigorously proscribed from the screen. Rootless characters, isolated in an abstract world, love, desire, hate as if they were the only survivors of a great cataclysm.15 This is the Beckettian backdrop for a cinema Sartre does not say of Hollywood realism, but the framework is therein which screenwriters wrack their brains searching for a characters motive in leav[ing] the living room for the kitchen. One could hardly expect there to be much free will in such a situation. In this context, The Chips are Down is an attempt to take up the problem of de-situated affect, make that problem more explicit and then plug it back into the situation that subtends it, to replace love stories or individual conicts in their social context (milieu social ). The explicitation of the problem of affect occurs, obviously enough, in the death administration; the representation of social context in the sounds of marching feet, the conspirators meetings, the scenes at the caf. This may seem to be merely the extension to lm of Sartres characteristic plea for a theater of situations. In the usual theorization of such a theater, Sartre contends that it replaces the conict of character with a conict of rights. But in The Chips are Down, the conict of rights is between the right to ones emotional lifeto love whom one wantsand the right of the group (the conspirators, the caf patrons, etc.) to require allegiance. In other words, it is a conict between character and social context. And just as the story apparently wavers between determinism and its opposite, so

MLN

1055

the motivation for its resolution wavers between allegiances to the group and to oneself. The Sartre who recaptures his affects in shooting Pierre (and Eve) reinforces the inescapability of the social at the same time. The Chips are Down thus represents a twofold progress in Sartres conception of the cinema over Being and Nothingness. On the one hand, it represents his commitment to a determinist understanding of the relationship between author and character. This is his commitment to a higher realism or a genetic realism. On the other hand, it represents his commitment to the social as overwhelming or supplanting the characteristic. The ontological dramatization that gave rise to the problem of responsibility for character now gives way to the social (or political) as the primary object of choice. The degree of Sartres commitment can be seen in imagining a contrary plot for the lm: were Pierre to choose Eve over his comrades (the English Patient version), the conspirators would be defeated, Eves husbands power would be consolidated further and their love would be impossible, given the militarists personal hatreds and his support for rigid class demarcations. The political undergirds the emotional. The movement from the depiction of character to the depiction of social milieu parallels a shift in Sartres understanding of cinema. In A Film for the Post-War Sartre lays out the distinction between cinema and theater as a distinction precisely between their inherent capacities for presenting the social:

On the screenand on the screen aloneis there a place for a crowd, maddened, furious or receptive. The novelist can evoke the masses; the theater, if it wants to represent them on stage, must symbolize them in a half-dozen characters who take the name and function of the chorus; only the cinema lets them be seen. And it is to the masses themselves that it shows them: to fteen million, twenty million viewers. Thus lm can speak of the crowd to the crowd.16

The elevation of sociopolitical context now issues in another repetition: the masses mimesis, de la foule la foule. The requirements of a genetic realism, Sartre implies, are circumvented by the image of a crowd placed before an actual crowd. On the screenon the screen aloneis there a place for a crowd, maddened, furious or receptive. But this repetition is acceptable only because the delay inherent in it might be overcome. In the Sartrean cinematic utopia, the masses in the movie theater somehow coincide with the masses on the screen; time is transcended; delay is erased.

1056

J. D. CONNOR

III. America Day by Day It was with the conception of postwar cinema as the opportunity to show the crowd to the crowd in mind, and his still unlmed screenplay for The Chips are Down behind him that Sartre made his rst trip to America. That trip resulted in two further important pieces of work on cinema: a series of articles on the Hollywood studio system and a review of Citizen Kane. This convergence is more than fortuitous. The studio articles are concerned with the typical industrial processes of the classical era: the quasi-rationalized system of story development, the typical political lm (Wilson) and labor threats to the systems continued viability (Mexico, where Sartres Typhus would become The Proud Ones). The review of Kane takes it up as a most atypical production, the production of one man. From the outset, then, what singles out Kane is its industrial status. No director had been more individual that Orson Welles. His legendary contract with RKO brought him into the system to be an auteur. In the newsreels and the newspapers, it appeared that the studio was bowing to the demands of the sovereign author-provocateur, that the enfant terrible was going to stand Hollywood on its head. Five years later, when the lm had nearly opped nancially and Welless Hollywood career had, again to all appearances, come apart, French criticism was only beginning catch up with his cultivated individuality. For all lm-lovers who had reached the age of cinematic reason by 1946, wrote Andr Bazin, the great critical mediator of genius and system, the name of Orson Welles is identied with the enthusiasm of rediscovering the American cinema; still more, he epitomizes the conviction, shared by every young critic at the time, of being present at a rebirth and a revolution in the art of Hollywood.17 In America, that revolution, or at least Welless central role in it, was already nearly dead; yet Sartre was still in thrall to Welless singularity. Citizen Kane is rst of all the work of one man. Orson Welles did everything: he is the lms scenarist, director and main actor.18 And like any auteur, Welles has a politics. Citizen Kane nds its place in a series of activities that all have the same meaning and the same goal: anti-fascism. Welles is an admirably gifted man whose primary concern is political, and the shared meaning of all his undertakings is . . . to win the American masses over to the cause of liberalism (601). Sartres easy shift from discussion of the lms production to discussion of the lms politics foreshadows, however dimly, much recent work on Hollywood. But his perception stems from the delay

MLN

1057

between the production and the reception, a delay that Sartre had already marked out as necessary to allow the viewer to reach the proper political understanding of a lm. Like hundreds of other American lms of the war years, Kane (RKO 1941) was kept out of France until 1946.19 In that time, Sartre found the distance to ask the most pertinent industrial-political questions: If everything Welles did was anti-fascist, and the fascists had been defeated, what was left to be done? And if everything he did was pro-liberal, yet he did everything himself, wasnt his practice at odds with his beliefs? In other words, the Rooseveltian arrogation of authority that could appear to be a temporary necessity in the struggle against fascism in 1940 was now, in 1946, either useless or dangerous. Sartre thus translates the distinction between production and reception into the distinction between the war and the postwar. But that distinction is also legible as the distinction between the lm and the culture it is part of. As Sartre puts it, Citizen Kane is surprising and new for America since it attacks American customs (60). Sartre calls this relationship intellectual (60). The project of the review, then, is to discover from Kane the limits of Welless politics in order to resolve the more general contradictions of the intellectual position. Sartre arrives in America with an understanding that the critical problem of postwar lm is to show the masses to themselves. After his trip, though, he places more emphasis on the show-er, the intellectual who mediates between the masses and their on-screen representations. But if his time in America convinces him of the overweening importance of the conditions of production, it does not entirely efface his central cinematic obsession with repetition. In America, repetition is reunited with its constitutive shadow concept: delay.20 This is what attracts Sartre to Kane. Instead of the usual stylistic hallmarksceilings and deep focus Sartre is attracted to the seemingly standard montages of the Kanes eating breakfast and Susan Alexander singing. This sort of montage usually appears, he says, in the margin of the main action to show political opinion or the inuence of an action on a collectivity or, in most cases, to indicate a transition (64). In other words, these montageslike the abortive newspaper distribution sequence in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington are those places where the masses appear to themselves. But in Kane the montage is not about articulating individual actions with collectives. Nor is it about bringing individual actions at different times into a coherent line, as the transition from, say, starlet to star is often shown in a series of newspaper headlines

1058

J. D. CONNOR

which sets the background for a transition from innocent aspirant to consummate cynic. In Kane, the montages do not provide narrative articulation at all. They characterize. This period of her life is summed up by a dozen or so shots of her face, miserable and laughable, with her sad eyes and mouth wide open, while we see always new and always different orchestras and spectacles, and newspapers that are emblazoned, in increasingly large characters, with the name of the singer (63). The montage creates the idea of lived generality as such. Where the unique narrative incident can only symbolize, working rhetorically, the reiteration of Susan Alexanders performance in Salammb, or the Kanes at the breakfast table does something else. Sartre explains:

[A]bove all else, there is a strange technique (but not really as new as all that) which gives certain images the value of a frequentive. In this story, indeed, we observe, He forced his wife to sing in all the theaters of America. This condenses into a single phrase a very large number of events lived from day to day. We wont nd the equivalent of that in It Happened One Night or Stagecoach where the adventure, which is singular and very short, is lived minute by minute. In Citizen Kane, Welles excels in that sort of abridgment which generalizes. (63) 21 It is as if the narrator told us: He forced his wife to sing everywhere; it was too much for her; she tried to tell him, etc. The result is that we understand exceedingly well the character and life passions of Kane. (64)

Sartre likens the characterizing generalization of the montage to the frequentive mood, a grammatical construction exemplied better in Andr Bazins paraphrase of Sartres example: For three years he obliged her to sing on all the stages of America. Susans anxiety would grow, each show would be an ordeal for her, one day she could no longer stand it . . . (AB 81). The frequentive mood is not to be confused with the incompleteness or usualness of the activity in the imperfect tense (she kept on performing). In English, the older frequentive gave us the class of -le verbs that represent the ongoing and slightly abstract action of the common verb: from wrest to wrestle or daze to dazzle. The frequentive is precisely the mood that conveys character, one in which the character is predetermined (Kanes in particular). All the actions that Kane repeats, or compels Susan to repeat, are characteristic examples. They are part of the pattern. Sartre associates the frequentive predetermination of character with the past tense narration of the Kane story as a wholethe ongoing investigation of the meaning of Rosebud (62). The mean-

MLN

1059

ing of the word is determined by the identity of the man, and, because he is dead, that identity is xed. In what Sartre calls the cinema of adventure, identity is in ux, the events are uncertain, The die is not yet cast [Les jeux ne sont pas faits.] In Citizen Kane, the die is cast (62). Thus at the time when for Sartre the ideal cinema will show the masses to themselves, Welles uses a technique ordinarily associated with the appearance of collectivities on screen and deploys it instead in the name of a deterministic theory of character. The technique is perverted, the notion it conveys is wrong, and the overall effect is of bad faith redoubled: Kanes bad faith becomes Welless bad faith in Kane. Citizen Kane wants to prove something (61). It proves that the American intelligentsia is rootless and totally cut off from the masses (64).22 Just as Sartre wanted the lm for the postwar to be one in which the masses could see themselves, coincide with themselves (seeing themselves seeing themselves), he wanted the writing of Les Chemins to make contact with the precise moment in which their reading began, i.e., the Liberation; the postwar. For Denis Hollier, Sartre alternates between recognizing the impossibility of simultaneity and repressing it. Something similar happens with characterological freedomsomething that Adorno, for example, draws attention to. But The Chips are Down does not vacillate. Instead, it drives home the lesson of the frequentive in Kane. And yet, as Sartre was completing it, he was writing What is Literature?, which is, for Hollier and Adorno, the central text for Sartres alternately redundant and impossible project. One would look in vain in the knot of texts that Sartre produced after the war for a series of recognitions or blindnesses that could add up to a cumulative change of heart. He does not discover something while writing The Chips are Down and forget it while writing What is Literature? The simpler and perhaps more elegant hypothesis is that Sartre knows something about cinema and he knows something else about theater and something else about criticism. The thing that Sartre knows about cinema, that, according to Hollier, he never quite learns about novels, is that his work as a writer is completely alienated from him long before the product reaches its audience. One can imagine that in speaking with someone my words are understood immediately, that in writing a note on a sheet of paper and sliding it across the table to its addressee an unfortunate but small gap is introduced, and that in writing a novel, having it typed, sending it off, getting it approved, getting it edited, having it composed, checking the galleys and nally succeeding in having

1060

J. D. CONNOR

it published an even more unfortunate gap has been introduced between my intention and its audience. But in writing for lm there is never for Sartre the illusion that it is his lm the way it is his novel, and so there is no desire to patch over the accidents of production. In his description of typical Hollywood writing, Sartre equates the assembly line work of making movies with delay and repetition:

The adaptation is entrusted to a writer, a screenwriter generally under contract. This imposes a variable delay, but one which is the longer the more important the lm. When the screenwriters work is done, he submits it to a producer whothis is the ruleis not satised and calls in a second screenwriter to rewrite it from beginning to end. It is thus not rare to see three or four writers successively modify a script.23

Screenwriting is thus a task far more amenable to the recognition of alienation. So inherent are the splits between the writers intention, its realization, and its reception that one suspects that the recognition in The Chips are Down of characterological dependence is not, in fact, a recognition at all. Instead, the violent reassertion of authorial or directorial control over the fates of characters who are, if not independent, then independent of them seems more an allegory of the writers own dependence and a desperate attempt to reestablish the preeminence of writerly intention. The writers pen must be Lucien Derjeus gun in order to cover the distance between intention and character, and it must magically transmit force as Derjeus gun shoots Eve over the phone line. If Sartre found the desperate subjection of characters to his will an excusable and necessary result of his industrial powerlessness, he faults Welles for asserting dramatic control in addition to his industrial power. Since Welles is not alienatedKane is his he has no allegorical reason to resort to the past-tense narration and the frequentive. He has the control that would allow him to realize his politics and chooses not to. Instead, he chooses to nd himself cast off from the masses. His separation is not inherent and industrial; it is accidental. Uniquely positioned to solve the intellectual problem, Welles fails. No wonder, for Sartre, he has abandoned the cinema for political journalism (60). If Welles, in 1946, is nally reuniting with his audience through the daily press that is because he was never a cineaste by profession, but rather a political jack-of-all-trades (60). By the same token, when Hollywood does manage to unite with its audience, it is not a transcendence of the limitations of the assembly line. Instead, it is, in

MLN

1061

the mathematical sense, a degenerate reunion. Sneak previews which are in principle a good thing (the principle here is the one that operates in A Film for the Post-War) have been a bit degenerate for some time. The publics taste, its sympathies, its antipathies are hardly fresh: it is Hollywood that for some years has made public opinion. As a result, its reactions are conditioned and, through the public, Hollywood consults itself.24 In the Hollywood system, then, both sides of the exchange between the screenwriter and audience are alienated; the writer from the audience, the audience from itself. IV. Mechanization Thus chastened by his American visit, Sartre returned to screenwriting and produced In the Mesh. The story is fairly simple. Jean Aguerra, the revolutionary dictator of a small country dependent on its oil production, is overthrown and put on trial. At that trial, the reasons for his forced mechanization of agriculture, his failure to nationalize the oil industry and his arrogation of power are gradually revealed. Aguerra is condemned to death, and his replacement nds himself in exactly the same binds. The trial also reunites Aguerra with his best friends widow, Hlne. She forgives him for having imprisoned and effectively killed her husband, ultimately declaring her love for Jean. Sartre claimed that the use of multiple points of view in the trial was a technique that was in the air. And to an extent it was. But the examples Sartre remembered in 1968 were Kane and Rashomon (1950), and only Kane had been made when he wrote In the Mesh. More than plural points of view, though, Sartre takes from Kane precisely the mood he most criticized in it: the frequentive. In the Sartrean frequentive, though, the repetition is not of a characteristic action, but one that inheres in the situation. I thought of a country in which it was really impossible to do anything else. A small, oil-rich country, for instance, which was wholly dependent on foreign countries for its livelihood.25 So in the small country of In the Mesh the frequentive becomes something like this: Every ve years the masses would revolt and their leader would be entrusted to nationalize oil. He would recognize that immediate nationalization would result in foreign invasion and would turn to his valet and ask for a whiskey. A more character-centered version of the frequentive is also legible in The Chips are Down. Imagine a summary such as this: Each life, Eve would be killed by her husband and Pierre would be shot by an

1062

J. D. CONNOR

informer. They would meet in death and be resurrected only (to choose) to meet the same death again. Sartre passed off The Chips are Down as a bit of determinist fun. But the political frequentive of In the Mesh proved harder to excuse. In 1968, Sartre described it this way: It was in 1946, too, that we began to discover the havoc caused by Stalinism. . . . One question worried me, and that was what, in a period of collectivization, is forcible and what is not? Which is the governing forcenecessity or man? As a matter of fact, Stalinism itself was not the issue. I simply started from a widely current assertion that Stalin could not have done other than what he did (ST 317). As he describes it, In the Mesh starts from Stalinism, but isnt about Stalinism. Instead, it is about a particular claim about Stalinism. Yet by writing the Stalinists apologetic absolute constraint into the situation, Sartre deprived himself of any purchase on the question Which is the governing force? since that force is necessity. By this charactercentered account, In the Mesh is the tragedy of a sincere Stalin, a man who came to power with revolutionary intentions . . . yet who nally resigned himself to a policy precisely the reverse because of the demands of a powerful neighbor (ST 317). As a political tract, In the Mesh runs counter to Sartres avowed politics; its compelling story is something like this: in cases where one really cannot do otherwise, at least revolution provides the occasion for voicing ones true though difcult feelings. Let the revolution come if it means that Hlne can proclaim her love for Jean. No doubt In the Mesh has its place in a narrative of Sartres postwar political career in which irtations with inimical positions (determinism, Stalinism) nally overwhelm his abilities at self-inoculation (fun, a worrisome question), culminating in The Communists and the Peace (1953). But there is another account available, the allegorical, and that account gives In the Mesh a place in the more exploratory history of Sartres study of cinema. Again the key comparison is the frequentive. Where the frequentive in The Chips are Down is legible as an index of Eve and Pierres ontological status as ctional characters, the political frequentive of In the Mesh is an index of Sartres industrial status as an alienated laborer. In order to capture that alienation, and Sartres understanding of it, I want to examine his representations of labor in In the Mesh as an allegory of that position. In the Mesh opens with a scene of absent work: A huge oil eld on the outskirts of a great city. Wells, storage tanks, cracking towers, warehouses. No sign of life. The alleys between the workshops are deserted, the machines at a standstill. Not a man at work. Even in

MLN

1063

ashback, the oil eld is the scene only of strikes, that is, of workers not working (but active in other ways). In the retrospective scenes of agricultural collectivization, the peasants are being led away in columns as their houses burn. Labor goes unseen throughout the screenplay, with one exception. When Lucien, Hlnes husband, Aguerras friend and a journalist committed to opposing Aguerras tyranny, appears in a cellar with four other men. They are printing a paper reduced in size on a hand press. The hand press, though, is atavistic. Luciens prior articles have appeared almost magically, the way newspapers appear in Hollywood lms, A rotary press spitting out newspapers. Huge headlines: The oil question. When shall we have elections? Oil again. Oil and democracy. Here we have a montagea frequentive montagethat Sartre puts to the classical Hollywood use of show[ing] political opinion or the inuence of an action on a collectivity (holding off showing the collectivitybut we know the masses have been led to revolt). At the same time, it is translatable as sentences that show us the character of the country a land of unceasing demands. Aguerras response to those demands is twofold. First, he tells Lucien (in the scene immediately preceding the rotary press) that the clamor for nationalization, a free press, and free elections is too early. Too early! Second, he drinks. The scene with the press is immediately followed by another frequentive montage:

Jean at his desk is reading a number of La Lumire. He looks dark and furious. He beckons to his valet. Whisky. The valet serves him and Jean drinks. Jean in uniform, standing. Whisky. The valet serves him and Jean drinks. In the same ofce Jean is seen in different costumes at different moments, ordering Whisky, whisky . . . and drinking. Jean in full dress uniform gets up from his desk, glass in hand. He walks straight but one feels that he is not entirely sober.

I want to juxtapose these frequentives (too early, the press, the drinking) a bit more precisely in order to elicit what one might call the industrial logic of In the Mesh. First, the argument between Aguerra and Lucien is about delay, in particular about Aguerras failure as the government to execute the demands of the people. That failure occurs in his ofce, across the desk where Aguerra will

1064

J. D. CONNOR

issue his decrees forcing the mechanization of agriculture. It is, in other words, an argument about the failure of Aguerras writing to coincide with his audiences demands. Second, the rotary press produces opinions that exactly and precisely coincide with the countrys demands, however premature. At the same time, though, we do not see Lucien writing. It is a mechanical coincidence. Third, the scenes of Aguerras drinking, which one wants to read as his guilt over not being able to meet his friend and the masses demands, take place as scenes of reading at his desk.26 The opposition, however implicit, between a retardatory, psychologically deep desk-writing (hand writing) and an instantaneous, agent-free machine-writing (journalism) is also and more apparently an opposition between the writing of a leader frustrated by his inability to control opinion and the writing of one who has merged with his apparatus, even if that entails a degenerate relationship to mass opinion. In their relationships to public opinion, Aguerra and Lucien act out and invert the two poles of the Hollywood system: Aguerra is the would-be idealist screenwriter who has made a necessity of delay; Lucien a would-be hack in the fortunate position of being on the side of freedom. That fortunate location allows him to go into independent production, controlling the writing (we nally see him at his desk), manning the hand press (collectively, ideally), and then, somehow, getting the samizdat La Lumire distributed despite truncheon-wielding policemen. He is a throwback to the industrial era of the eponymous brothers. The utopian moment of underground or resistance authorship aside,27 there is only one person who is in a position to comprehend the two sides of the industrial/political equation: Hlne. Between the publication of La Lumires last edition and Luciens arrest, she sits at her secretarys desk in Aguerras ofce, on edge. She stares at the clock, whose hands show ten oclock, then the hands disappear and a black disk which whirls rapidly on its own axis blots out the dial. . . . The whirling disk at last bursts with the noise of an explosion and Hlne falls forward on her table, her head in her hands. The mechanism and the manual (her mains) cross here, just as Lucien and Aguerra cross in Hlne. Although she is not a mass readership, she is here the viewer of something remarkably like a lm, projected (for us) as the black disk; a lm of a lm spool, the evolution of the rotary press from the earlier montage. It is as though her body cannot take the stress on it from the relentless repetitions of the dilemma, Jean or Lucien; delay or instantaneity.

MLN

1065

By 1946, then, Sartres understanding of cinema has in a sense returned to his earlier concentration on lm as a medium. But in the return Sartre now understands the irruption of the material as either a brief utopian moment of absolute presence, of absolute control of the entire process (Luciens hand-pressing) or as an unsustainable and momentarymetastableconsciousness of the opposition between Luciens instantaneity and Aguerras insistence on delay. That opposition is then visualizable as precisely the lmic mechanism (delay and movement) behind which lies the ickering that was so important to Being and Nothingness. There, ickering was the emblematic exhibition of bad faith; here it captures Hlnes bad faith in her denial of her attraction to Jean. It encapsulates Sartres own dilemma: his recurrent desire for immediate connection with the masses and his knowledge that, in the cinema, alienation is inevitable.

NOTES

1 Jean-Paul Sartre, Quiet Moments in a War: The Letters of Jean-Paul Sartre to Simone de Beauvoir, 19401963, ed. Simone de Beauvoir, tr. Lee Fahnestock and Norman MacAfee (New York: Charles Scribners Sons, 1993), 251. Further citations in the text. 2 QM 254. Sartres Typhus, later lmed as The Proud Ones, was purchased later. 3 Michel Contat and Michel Rybalka, The Writings of Jean-Paul Sartre, tr. Richard C. McCleary (Evanston, IL: Northwestern UP, 1974), 1:601. Their appendix on the cinema is still the best source for considerations of Sartres contributions, gathering as it does many of Sartres interviews. 4 Contat and Rybalka, 2:53. 5 Iris Murdoch, Sartre: Romantic Rationalist (New Haven: Yale UP, 1953), ix. In one of the few discussions of the passages on language from Being and Nothingness, Dominick LaCapra (A Preface to Sartre [Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1978], 138) makes the standard deconstructive point about Sartres linguistics:

This metaphysics of meaning reduces language to the opposition between a living truth of the intentional, self-projecting for-itself and a deadly counternality of rule-bound structure (parole and langue in another formulation of the metaphysical opposition)an opposition that language both generates and overows. In this conception, Sartre does not see language as simultaneously decentering the speaking subject and enabling the speaking subject to attempt to center language on himself and his projects. He unproblematically presents language as centered on the intentional subject or agent.

That Sartre felt the difculties of this position, and that most of his discussion is an attempt to refute the possibility that language is the active agent and that the speaker/writer/man is an effect of that language is absent from this description. From a complementary perspective, Denis Hollier says that for Sartre, the experience of language is no more than a local, belated and secondary modality of a private experience of meaning preceding and encompassing it. Like Roland Barthess prototypal man, Sartres can be called Homo signicans. But it is not because he speaks; it is because he exists (The Politics of Prose: Essay on Sartre, tr., Jeffrey Mehlman [Minneapolis: U Minnesota P, 1991], 59). For LaCapra, Sartre

1066

J. D. CONNOR

6 7

10

11

12

13 14 15 16 17 18

19

has underestimated the autonomy of language and consequently fallen into a metaphysical trap; for Hollier, Sartre has overestimated the importance of meaning and hence underestimated the uniqueness of language. Michael Syrotinski, Defying Gravity: Jean Paulhans Interventions in Twentieth-Century French Intellectual History (Albany, NY: SUNY P, 1998), 12. Further citations to DG. Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness, tr. and introd. Hazel E. Barnes (New York: Gramercy, 1956), 516. Further citations to BN in the text. I cite this early translation because it captures the most inuential version of the text in English. This gives rise to a characteristic Sartrean problem. On the one hand, he does not wish to invalidate a priori the study of linguistics. On the other, if there are no consequences to his understanding of grammar, then it becomes interchangeable with linguistic explanations (as, for example, force models and energy models can yield the same physics). One might think of this as a simultaneous fear of nominalism on the one side and pragmatism on the other. For Ludwig Wittgenstein in his critical phase, one simply cannot, just as one cannot give oneself money (he uses the image of one hands passing it). In the second part of the Philosophical Investigations, though, that quick rejection is withdrawn, and self-delusion is again a eld of study. The self-consciousness of the waiters imitation puts him on the line between these two dramas, a line that Sartre later associates with Jean Genet (and homosexuality in general) in Saint Genet. Whether this is an elaboration of bad faith or (what seems more likely given the gap between the formulations) a change in the nature of the concept is of less importance here. The question of whether the waiter wants to be the waiter he imitates or whether he simply wants to imitate would require additional, institutionally-funded research. It is the need to escape from needing to choose all the time (from needing to think or feel anything all the time) that drives Wittgensteins examination of knowing a word. Sartres recourse to grammar here has certain similarities with William Jamess account of these same difculties in Psychology (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1981), 1007. Contat and Rybalka 1:163, quoting Le Figaro, April 29, 1947. Jean-Paul Sartre, Les Jeux sont faits (London: Nagel, 1947), 138. Further citation in the text. Jean-Paul Sartre, Un lm pour laprs guerre, Lcran franais incorporated in Les Lettres franaises, April 1944, 3. The translation is mine. Ibid. Andr Bazin, Orson Welles: A Critical View, tr. Jonathan Rosenbaum (Los Angeles: Acrobat, 1991), 33. Further citations to AB in the text. Jean-Paul Sartre, Citizen Kane, tr. Dana Polan, Post-Script 7 (Fall 1987): 605, 60. Further citations in the text. The article was published as Quand Hollywood veut faire penser in Lcran franais, August 1, 1946. The triggering mechanism for this was the Blum-Byrnes accord, signed May 28, 1946. Comparative statistics are available in Patricia Hubert-Lacombe, Laccueil des lms amricains en France pendant la Guerre Froide (19461953), Revue dhistoire moderne et contemporaine 33 (April 1986): 30113; Jacques Portes describes the background of the accords and their reception in Les origines de la lgende noire des accords Blum-Byrnes sur le cinma, Revue dhistoire moderne et contemporaine 33 (April 1986): 31429. Portes compellingly argues that the reaction to the

MLN

1067

20

21 22

23

24

25

26

accords set the pattern for anti-Americanism (and then anti-Marshall Plan sentiment) in France and that this in turn forced the State Department to consider cinema as an important element in international cultural relations. Denis Hollier nds that it is characteristic of Sartres work of this period that its production coincides with its reception. He also assumes that Sartre is, if not exactly unaware of this requirement, immune to its impossibility. (See Hollier, The Politics of Prose: Essay on Sartre.) While that may be the case with Les Chemins de la libert, it is not the case with the review of Citizen Kane. Why that is not the case I address below in my discussion of the relationship between screenwriter and character. I have altered the English translation from frequentative to frequentive to accord with general American usage. This is perhaps the place to say that whatever the relationship between intellectuals and masses might have been in America in the 1940s, Welless understanding of that relationship is not best understood through the montages Sartre is so attracted to. Instead, one would do well to look at the scenes involving commercial signs and windows, particularly when the newspaper circulation gures begin to appear in them. There are not, in any usual sense, masses depicted in Citizen Kane; there are, however, large numbers, which are the relevant operationalizations of masses in classical Hollywood. Sartre, Comment les amricains font leurs lms, Combat, March 30, 1945, 1. The series of ve articles on Hollywood for Combat has never, to my knowledge, been reproduced (much less translated). Translations are my own. Ibid. This image of the Hollywood lm as directed at itself not in the modernist sense of drawing attention to its own elaboration or materiality but in the sense of its success amounting to having sealed itself against any exterior reaction has certain similarities with Horkheimer and Adornos account. The differences that Sartre sees Hollywood, and Disney in particular, evolving toward the thinking picture that will carry an educational message (good Zanuck) while for Horkheimer and Adorno the signicance of Donald Duck is that he takes his punishment so the audience will learn to take theirsare legion. What interests me is the assumption that Hollywood lms have (naturally) reached this point of socio-aesthetic closure, an assumption more prevalent in Dialectic of Enlightenment than in Sartres Combat articles. Given the massive outlay of energy and capital on the part of the major studios to rationalize the reception of their products, it seems less the case that Hollywood was in fact consulting itself and more that Hollywood wanted to. In other words, Horkheimer and Adorno and Sartre are guilty of believing the studio hype. Jean-Paul Sartre, Sartre on Theater (New York: Pantheon, 1976), 316. The material on In the Mesh comes from observations Sartre made to Bernard Pingaud. They were published in Thtre de la ville, November 1968. Further citations to ST in the text. These scenes help show just how denitively Sartre was inuence by Kane, a lm, if one needs to be reminded, centrally about newspapers and their opinion, and that Sartres eventual approval of Welles (if not Kane) stems from his having given up movies for journalism. More particularly, after Susan Alexanders opening performance, Kanes best friend Jedediah (Joseph Cotton) is supposed to write a glowing review. Instead, he begins a pan and then drinks until he passes out. Kane steps in and nishes the review as negatively as Jed began it; then res him. Whatever the complicated motives of Kane (and they are complicated enough that one would object to Sartres characterization of his character on these

1068

J. D. CONNOR

grounds alone), this scene of a man writing his own critique is at least a theoretical possibility in In the Mesh. Who is to say that Aguerra might not be (or imagine himself to be) the author of the rotary press headlines? We do not see them written for a reason. 27 Sartre rhapsodizes about this moment, and justies the postwar purge, in The Republic of Silence, The Atlantic Monthly, December 1944, 3940.

You might also like

- Unit6 Motorbikes Pg128 - 147Document20 pagesUnit6 Motorbikes Pg128 - 147Omar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Intelligent Business Elementary WBDocument97 pagesIntelligent Business Elementary WBrogervin88% (8)

- LTDocument48 pagesLTOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Glasses, Window System & Mirrors: SectionDocument24 pagesGlasses, Window System & Mirrors: SectionOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Maintenance: SectionDocument42 pagesMaintenance: SectionOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Front Suspension: SectionDocument16 pagesFront Suspension: SectionOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- ENGINE LUBRICATION SYSTEMDocument24 pagesENGINE LUBRICATION SYSTEMOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Accelerator Control System: SectionDocument4 pagesAccelerator Control System: SectionOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- MTDocument38 pagesMTOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- LTDocument48 pagesLTOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Alphabetical Index: SectionDocument7 pagesAlphabetical Index: SectionOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Instrument Panel: SectionDocument6 pagesInstrument Panel: SectionOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- FLDocument18 pagesFLOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- FWDDocument2 pagesFWDOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- ExDocument6 pagesExOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Front Axle: SectionDocument8 pagesFront Axle: SectionOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- ExDocument6 pagesExOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- FLDocument18 pagesFLOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- EmDocument204 pagesEmOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- EiDocument32 pagesEiOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- CLDocument16 pagesCLOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- EiDocument32 pagesEiOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Body, Lock & Security System GuideDocument40 pagesBody, Lock & Security System GuideOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- DiDocument44 pagesDiOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Brake Control System: SectionDocument30 pagesBrake Control System: SectionOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Nissan Electronic Service Manual: 1998 ModelDocument1 pageNissan Electronic Service Manual: 1998 ModelOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- CoDocument48 pagesCoOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- BRDocument34 pagesBROmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Audio, Visual & Telephone System: SectionDocument12 pagesAudio, Visual & Telephone System: SectionOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Accelerator Control System: SectionDocument8 pagesAccelerator Control System: SectionOmar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Absence of MaliceDocument4 pagesAbsence of MaliceSagun BhartiyaNo ratings yet

- The Lifecycle of A Television Cult Classic Through The Lens of TwinDocument12 pagesThe Lifecycle of A Television Cult Classic Through The Lens of Twinapi-317588381No ratings yet

- Sangeet Sandhya 3Document6 pagesSangeet Sandhya 3architect AJNo ratings yet

- Epic Fail Live Chat TranscriptDocument20 pagesEpic Fail Live Chat TranscriptinkpopNo ratings yet

- Movie Review: The Little PrinceDocument14 pagesMovie Review: The Little Princedella sonniaaNo ratings yet

- 800 OnwardsDocument3 pages800 Onwardssharmaishita6311No ratings yet

- The Lion King - NarrativeDocument2 pagesThe Lion King - NarrativeFitrianingsih FitriiNo ratings yet

- CCVF BrochureDocument35 pagesCCVF BrochurekamalchakilamNo ratings yet

- Movie Assignment Data DictionaryDocument4 pagesMovie Assignment Data DictionaryManjunath DvsNo ratings yet

- Dil Ne Yeh Kaha Hai Dil Se Hindi Love Song LyricsDocument5 pagesDil Ne Yeh Kaha Hai Dil Se Hindi Love Song LyricsHushein RasheethNo ratings yet

- Irrigation & CAD DepartmentDocument2 pagesIrrigation & CAD DepartmentA. D. PrasadNo ratings yet

- 1942: A Love Story Is A 1994 Indian Hindi Patriotic RomanceDocument5 pages1942: A Love Story Is A 1994 Indian Hindi Patriotic RomanceRajesh Reghu Nadh NadhNo ratings yet

- ProRes 422 WhitepaperDocument11 pagesProRes 422 WhitepaperffwdcoNo ratings yet

- The New Wave and Dogma95Document9 pagesThe New Wave and Dogma95ThisgirlisnotonfireNo ratings yet

- PVR Cinemas SWOT and 7Ps analysisDocument8 pagesPVR Cinemas SWOT and 7Ps analysisPreethi Rajasekaran50% (2)

- Psychological Outlook of CinemaDocument10 pagesPsychological Outlook of CinemaDevesh PurbiaNo ratings yet

- Durban International Film Festival - 2010 ProgrammeDocument120 pagesDurban International Film Festival - 2010 ProgrammeSA Books50% (2)

- Auslander, Philip - Surrogate Performances - On Performativity - Walker Art Center PDFDocument22 pagesAuslander, Philip - Surrogate Performances - On Performativity - Walker Art Center PDFLaura SamyNo ratings yet

- Delhi High Court: Page NoDocument392 pagesDelhi High Court: Page Nomedhasingh1498No ratings yet

- Photography and CinemaDocument161 pagesPhotography and Cinemaapollodor100% (6)

- Carol Vernallis TheoryDocument2 pagesCarol Vernallis TheorylatymermediaNo ratings yet

- Historical Dictionary of French CinemaDocument495 pagesHistorical Dictionary of French CinemaAndreea Alexandra Vraja100% (1)

- Around The World in 80 DaysDocument9 pagesAround The World in 80 DaysIhsan1991 YusoffNo ratings yet

- Naah Lyrics - Hardy Sandhu FeatDocument6 pagesNaah Lyrics - Hardy Sandhu FeatAli100% (1)

- Batch 1: (9:00 Am - 12:00 NN)Document20 pagesBatch 1: (9:00 Am - 12:00 NN)Klaribelle VillaceranNo ratings yet

- RDB - FilmatographyDocument3 pagesRDB - FilmatographychandrabhanooNo ratings yet

- Classic Horror Films and The Literature That Inspired Them (2015) PDFDocument373 pagesClassic Horror Films and The Literature That Inspired Them (2015) PDFWanda Mueller100% (7)

- Details of Apios, Pios & Appellate Authorities Department of Horticulture, T.S., HydDocument3 pagesDetails of Apios, Pios & Appellate Authorities Department of Horticulture, T.S., HydvijaykannamallaNo ratings yet

- Urdu MSDocument6 pagesUrdu MSWaseem AkramNo ratings yet

- HappiestMinds Rajyotsava 2017 PosterDocument29 pagesHappiestMinds Rajyotsava 2017 PosterCvblrNo ratings yet