Professional Documents

Culture Documents

LM 6190 - Final Paper - PLCs - Peirce

Uploaded by

jlpeirceCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

LM 6190 - Final Paper - PLCs - Peirce

Uploaded by

jlpeirceCopyright:

Available Formats

Jennifer Peirce LM 6190 August 5, 2013 Final Paper School Librarians Role in School-Based Professional Learning Communities

Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) have proven to be an effective means for improving teacher practice and an opportunity for meaningful collaboration between teachers and library media specialists. In PLCs, teachers and other staff members work together to improve instruction and student learning by reflecting on current practices, looking for areas in which to focus and develop, putting those changes into practice, and assessing the outcomes of those changes. Librarians can contribute to PLCs in many important and unique ways leading to the improvement of the quality of PLCs, increased opportunities for collaboration with teachers, and promotion of the school library program. In order for a school librarian to take and active and successful role in school-based PLCs, especially when he or she has never worked with PLCs before, it is important to understand what PLCs are, what the characteristics of effective PLCs are, and the different roles they may play in PLCs in order to most effectively meet teachers needs. PLCs are a form of collaborative professional development in which teachers and other staff in a school meet in groups based on grade level, subject area, or another common interest or need. The members of a group meet regularly to plan collaboratively and make changes to improve their teaching and learning for their students. PLC groups often select an area of focus related to improving the quality of instruction and learning and reflect on their understandings, beliefs, and practices in this area. They discuss their ideas with other members of the PLC and work together to solve problems, plan, and learn. This learning is generally self-directed with the

experiences and collective knowledge of the group serving as a source of information. (Linder, Post, & Calabrese, 2012) PLC groups may also utilize professional literature or professional development focused on their needs to improve their practice. Group members may observe one another and provide feedback. PLCs are characterized by a number of core beliefs: (1) that staff professional development is critical to improved student learning; (2) that this professional development is most effective when it is collaborative and collegial; and (3) that this collaborative work should involve inquiry and problem solving in authentic contexts of daily teaching practices (Servage, 2008, p. 63). These core beliefs are reflected in a number of attributes that are generally associated with PLCs. Administrators provide support to PLC groups, but they share leadership with the other staff members by allowing them to make decisions regarding the direction of the PLC (Brasfield, 2011). PLCs also utilize the collective creativity of the group members through the sharing of ideas and working together to solve problems; plan lessons, units, or courses of action; and learn from each other (Brasfield, 2011). PLC groups work together with a shared purpose (Servage, 2008) as well as shared values and vision with clear goals and standard norms for participation in these groups (Brasfield, 2011). It is important that there are supportive conditions within a group in order to create a level of trust in which members of the group feel comfortable sharing and working together (Brasfield, 2011). According to Linder, Post, and Calabrese (2012), PLCs are most effective when group members have common interests and a mutual purpose and when there is a sense of autonomy within the group by them being able to decide what they would like to focus on, how they want to study, and what activities they want to implement in their classrooms. They also found that regularly scheduled meetings and a final presentation on the groups findings will also help PLCs

to be most effective. This presentation increases ownership and accountability, as does posting group meeting agendas and minutes for the entire school community to see. This practice has the added benefit of allowing school community members outside of the immediate PLC group, such as a school librarian or an administrator, to contribute their expertise or other resources when they see a need. Dees, Mayer, Morin, and Willis (2010) also identify several elements that contribute to the success of learning communities. Groups must have effective communication, a clear set of goals, and administrative support. The focus must be on improving teaching and learning. Planning for instructional needs should be data driven. Group members share their collective knowledge and individual expertise. By allowing teachers to select the topic and work together, professional development becomes meaningful and engaging. Brasfield (2011) notes that successful professional learning communities have full participation and system-wide support and the changes in teaching practices should be driven by research and results observed within the school. Servage (2008) asserts that in order for PLCs to create transformative learning experiences that lead to systemic and sustained changes in teaching practices, teachers need to understand the philosophies behind the changes, be guided by shared norms and values, and be willing and able to critically explore, articulate, negotiate, and revise their beliefs about themselves, their students, their colleagues, and their schools (p. 70). PLCs need to create opportunities for teachers to hold open-ended conversations regarding their educational beliefs and values, what it means to teach and to learn, and the characteristics of their school communities (Servage, 2008).

Professional development opportunities allow for school librarians to share their knowledge and make connections to the school library for teachers and administration and gives the school library program a larger role in the school (Harvey, 2013). Participation in PLCs is an important way for school librarians to build relationships with teachers and to be seen as valuable members of the school community by allowing them to share their knowledge and creating opportunities for collaboration with teachers. Working with PLCs also allows school librarians to promote technology integration as well as reading and literacy (Dees, Mayer, Morin, & Willis, 2010). Because school librarians have a unique position within a school by having access to so many resources and a whole-school perspective, they are in a key position to be involved in significant ways in PLCs (Brasfield, 2011). Hughes-Hassel, Brasfield, and Dupree (2012) offer eight different roles a school librarian can play in a PLC: information specialist, staff developer, teacher and collaborator, critical friend, leader, researcher, learner, and student advocate. An obvious role librarians can play within a PLC is as an information specialist. As an information specialist, they may be able to suggest and provide relevant professional literature and research for PLC members to use to inform themselves (Brasfield, 2011). Brasfield also suggests that school librarians participating in PLCs read professional literature in advance in order to better anticipate the needs of the group and help jump-start conversation within the group. They may suggest resources and technology tools to be used in instruction, share alternative pedagogical and assessment strategies, and demonstrate their use to teachers. Coming to PLC meetings with strategies and ideas already in hand can help teachers to see the school librarian and the school library program as a valuable resource (Hughes-Hassel, Brasfield, &

Dupree, 2012). As information specialists, it is very important that school librarians stay informed about new resources and continually share them with teachers. In a PLC setting, staff development should be focused, sustained, collaborative, and results-oriented. This perspective opens up a myriad of opportunities for school librarians to provide ongoing, personalized, just-in- time staff development (Hughes-Hassel, Brasfield, & Dupree, 2012, p. 32). Because school librarians often work with multiple PLCs within a school and know the curriculum taught throughout the school, they are in a unique position to know what professional development teachers may want and need (Brasfield, 2011). They may target training opportunities for the whole school, small groups, or individuals, depending on what teachers need or desire. A school librarian might meet with a PLC to do training on a resource and then create a follow up plan to work individually with teachers for further training or collaboration (Harvey, 2013). Because teachers, working in their PLC groups, have identified these needs, they would be more likely to participate in these trainings and utilize what they have learned in their teaching. The opportunity for continued support form the school librarian can also increase the likelihood of implementation of changes in teaching practice. As a teacher and collaborator, a school librarian can work within a PLC setting to help teachers plan units that integrate a variety of curriculum areas, incorporate information literacy and technology, and foster inquiry-based learning (Harvey, 2013). As Harvey puts it, PLCs are a collaboration gold-mine, presenting many opportunities to work with teachers on projects. B y collaborating with teachers in planning and instruction, librarians are able to integrate information and technology standards into classroom instruction. They also should align library instruction with the PLC teams goals (Hughes-Hassel, Brasfield, & Dupree, 2012). They may also train both teachers and students in using new technology tools or resources that would be

useful within a content area by modeling the tool for teachers and students, setting up accounts when necessary, and facilitating the use of this tool by the teacher and students (Brasfield, 2011). Successful collaboration will beget more opportunities for collaboration as other teachers will want to have the same learning experiences for their students (Dees, Mayer, Morin, & Willis, 2010). Collaborating with teachers on projects also opens up opportunities to be a critical friend within a PLC setting. After collaborating on a unit or lesson, the teacher and school librarian can reflect together on what worked and what could be improved upon or changed (Hughes-Hassel, Brasfield, & Dupree, 2012). This reflection can be very valuable to both the teacher and to the librarian. Participating in this reflective practice will also build stronger partnerships between the teacher and school librarian, which also serves to improve the outcome of future collaborations (Hughes-Hassel, Brasfield, & Dupree, 2012). When working with a PLC group, school librarians can also lead and model the practice of critical reflection and feedback in order to help standardize the practice within and amongst school PLC groups, increase its effectiveness, and reduce the likelihood of it causing distrust or discomfort when teachers use this practice in their PLCs (Brasfield, 2011). School librarians have an important role in a school and, therefore, should act as a teacher leader within the school and as a leader in PLCs. Taking on the role of leader in a PLC will help the school librarian to build relationships with teachers and influence change (Hughes-Hassel, Brasfield, & Dupree, 2012). As a leader, school librarians can also facilitate discussions in a PLC that can help teachers to see beyond their own curriculum standards and consider alternative methods and strategies for instruction. As a leader, it is important that school librarians not solve the problems of the group for them or take over. Instead, to be most effective in their leadership

role, they should use their skills to identify and promote the leadership in others. In every collaboration, a leaders primary goal should be identifying and promoting the qualities of the other, so the capacity of that individual grows (Mackley, 2013, p. 25). This leadership opportunity can also allow librarians to share the vision of the library and demonstrate the connection between the school library program and student learning (Hughes-Hassel, Brasfield, & Dupree, 2012). Because action research plays a critical role in a PLC, school librarians experience and knowledge of research strategies can be very beneficial to a PLC group. Not only can they share their knowledge in this area, but they can also use and improve their own research skills by conducting action research with teachers. In doing so, librarians can help to establish themselves as instructional leaders and demonstrate the school librarys value in relation to learning and achievement (Hughes-Hassel, Brasfield, & Dupree, 2012). By participating in a schools content area PLCs and in school librarian PLCs, school librarians can also act in the role of learner (Hughes-Hassel, Brasfield, & Dupree, 2012). When working with content area PLCs, school librarians can learn more about effective teaching practices and the curriculum within a subject area. This can help to strengthen their knowledge of the schools curriculum, which can enable the school library program to better meet the instructional needs of the classroom. Participating in school librarian PLCs can help librarians to improve their skills as librarians and to improve the library program to better meet the needs of student learning (Hughes-Hassel, Brasfield, & Dupree, 2012). A final role school librarians might play in a PLC is that of a student advocate. They can act to help teachers foresee the needs of the students and to become aware of students differing learning styles (Brasfield, 2011). They can then help teachers and students to find resources that

will most appropriately meet those needs. The wider view of a school that school librarians tend to have can make them a true and important advocate for students (Hughes-Hassel, Brasfield, & Dupree, 2012). No matter what role a school librarian takes within a PLC, there are a few more strategies that can help school librarians to be successful when interacting with PLCs. Even if unable to attend a PLC meeting, school librarians should stay informed about what is occurring in the PLCs by attending school leadership team meetings, reading the minutes and agendas of the PLC group meetings, and by meeting with PLC team leaders (Brasfield, 2011). They can then go to individual teachers with resources and ideas (Dupree, 2012). Dupree also notes the importance of forging personal relationships with teachers, to have a good understanding of where the teachers are coming from of their struggles and concerns and to work with them to help brainstorm ways of improving instruction. The ultimate goal is for your teachers to see you as an instructional partner and a valuable resource in increasing student achievement (Dees, Mayer, Morin, & Willis, 2010, p. 10)

Bibliography Brasfield, A. L. (2011). School Librarian Participation in Professional Learning Communities. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, School of Information and Library Science, Chapel Hill, NC. Cox, E. (2011). Vital Conversations: Professional Learning Communities and School Librarians. School Library Monthly , 27 (7), 35-36. Dees, D., Mayer, A., Morin, H., & Willis, E. (2010, October). Librarians as Leaders in Professional Learning Communities through Technology, Literacy, and Collaboration. Library Media Connection , 10-13. Dupree, D. (2012). A Case Story: A New School and PLCs. School Library Monthly , 28 (7), 11-17. Harvey, C. A. (2013). Putting on the Professional Development Hat. School Library Monthly , 29 (5), 32-34. Hughes-Hassel, S., Brasfield, A., & Dupree, D. (2012). Making the Most of Professional Learning Communities. Knowledge Quest , 41 (2), 30-37. Linder, R. A., Post, G., & Calabrese, K. (2012). Professional Learning CommunitiesL Practices for Successful Implementation. The Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin , 13-22. Mackley, A. (2013). Murmuration: Building a Participatory Culture. Teacher Librarian , 40 (4), 23-27. Servage, L. (2008). Critical and Transformative Practices in Professional Learning Communities. Teacher Education Quarterly , 63-77.

You might also like

- Grants For School LibrariesDocument2 pagesGrants For School LibrariesjlpeirceNo ratings yet

- SIRS Issues Researcher User GuideDocument2 pagesSIRS Issues Researcher User GuidejlpeirceNo ratings yet

- Collection Assessment PlanDocument2 pagesCollection Assessment Planjlpeirce0% (1)

- Reflection On UELMA ConferenceDocument4 pagesReflection On UELMA ConferencejlpeirceNo ratings yet

- NoodleTools Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesNoodleTools Lesson PlanjlpeirceNo ratings yet

- Library Media Center Policy and Procedures Manual For Kearns High SchoolDocument27 pagesLibrary Media Center Policy and Procedures Manual For Kearns High SchooljlpeirceNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Amendments LucidPress Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesConstitutional Amendments LucidPress Lesson PlanjlpeirceNo ratings yet

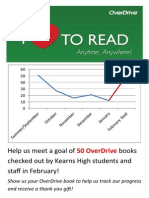

- Help Us Meet A Goal of Books Checked Out by Kearns High Students and Staff in February!Document1 pageHelp Us Meet A Goal of Books Checked Out by Kearns High Students and Staff in February!jlpeirceNo ratings yet

- Kindle Use Agreement For StudentsDocument1 pageKindle Use Agreement For StudentsjlpeirceNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 1994Document12 pages1994Marcelo RufinoNo ratings yet

- San Antonio Village Scout RegistrationDocument8 pagesSan Antonio Village Scout RegistrationRogelio GoniaNo ratings yet

- Registration No.:: Confirmation Page For Ctet - Sept 2015 (For Candidate Record)Document1 pageRegistration No.:: Confirmation Page For Ctet - Sept 2015 (For Candidate Record)Shaikh JilaniNo ratings yet

- IELTS Blog CohesionDocument5 pagesIELTS Blog CohesionSaidriziNo ratings yet

- Rubrics For Classroom Cleanliness AssessmentDocument5 pagesRubrics For Classroom Cleanliness AssessmentJae Tuffie Katnees88% (8)

- Analytical Exposition Text ExplainedDocument5 pagesAnalytical Exposition Text ExplainedNadya LarasatiNo ratings yet

- Check Your English VocabularyDocument2 pagesCheck Your English VocabularyLenonNo ratings yet

- Masacupan Resume 6.30.2011Document1 pageMasacupan Resume 6.30.2011Melorie MasacupanNo ratings yet

- Thematic Unit For 6th GradeDocument3 pagesThematic Unit For 6th Gradeapi-295655000No ratings yet

- tmc1 OrientationDocument19 pagestmc1 OrientationEmmerNo ratings yet

- Active Learning: An Introduction Richard M. Felder Rebecca BrentDocument7 pagesActive Learning: An Introduction Richard M. Felder Rebecca BrentGedionNo ratings yet

- AmeriCamp BrochureDocument12 pagesAmeriCamp BrochureAmeriCampNo ratings yet

- School Learning Action Cell SLAC TopicsDocument1 pageSchool Learning Action Cell SLAC TopicsNadine CasumpangNo ratings yet

- CV-Academic QualificationDocument2 pagesCV-Academic QualificationSAHANA BHARATHNo ratings yet

- ENG 154-C Catch Up Plan Q3 2016-2017Document6 pagesENG 154-C Catch Up Plan Q3 2016-2017buboybeckyNo ratings yet

- Science Quest CampDocument3 pagesScience Quest CampMapleGroveSchoolNo ratings yet

- TSCI Paper Educ516Document12 pagesTSCI Paper Educ516james100% (1)

- School Board Meeting ReflectionDocument3 pagesSchool Board Meeting Reflectionapi-302398531No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan of Writing Integrating GrammarDocument3 pagesLesson Plan of Writing Integrating GrammarMohamad AzmanNo ratings yet

- "Engineering Design of Products" (E/ME105) Focus: Guatemala Fall Quarter 2006-2007Document45 pages"Engineering Design of Products" (E/ME105) Focus: Guatemala Fall Quarter 2006-2007Alex CortezNo ratings yet

- Grade 2 MathDocument36 pagesGrade 2 Mathrica villanueva100% (2)

- Improving Fluency in Young Readers - Fluency InstructionDocument4 pagesImproving Fluency in Young Readers - Fluency InstructionPearl MayMayNo ratings yet

- Class XI English Hornbill PDFDocument127 pagesClass XI English Hornbill PDFprashanthNo ratings yet

- Hundred Volume 1 Chapter 1Document30 pagesHundred Volume 1 Chapter 1Suryo UtomoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 SummaryDocument1 pageChapter 3 Summaryapi-250139422No ratings yet

- Persuasive EssayDocument4 pagesPersuasive EssayJhonfred VelascoNo ratings yet

- Ah102 Syllabus 20180417Document7 pagesAh102 Syllabus 20180417api-410716618No ratings yet

- Narrative Writing UnitDocument47 pagesNarrative Writing Unitapi-290541111No ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan for Teaching Respect for One's CountryDocument1 pageDaily Lesson Plan for Teaching Respect for One's CountryNorizah BabaNo ratings yet

- Esl ResumeDocument2 pagesEsl Resumeapi-240469865No ratings yet