Professional Documents

Culture Documents

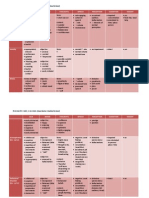

DSM 5 Chart

Uploaded by

Jose Luis Gonzalez Celis100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

795 views7 pagesDSM-5 diagnostic criteria do not reflect significance of language content and form. Diagnostic features indicate that nonverbal communication should be assessed "relative to cultural norms" individual will be given a diagnosis of "autism spectrum disorder" with three levels of severity.

Original Description:

Original Title

DSM-5-Chart

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentDSM-5 diagnostic criteria do not reflect significance of language content and form. Diagnostic features indicate that nonverbal communication should be assessed "relative to cultural norms" individual will be given a diagnosis of "autism spectrum disorder" with three levels of severity.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

795 views7 pagesDSM 5 Chart

Uploaded by

Jose Luis Gonzalez CelisDSM-5 diagnostic criteria do not reflect significance of language content and form. Diagnostic features indicate that nonverbal communication should be assessed "relative to cultural norms" individual will be given a diagnosis of "autism spectrum disorder" with three levels of severity.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 7

DSM-5

(Criteria and Major Changes for SLP-Related

Conditions)

ASHA Comments*

(ASHA Recommendations Compared to

DSM-5 Criteria)

Potential Practice Implications

Austism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Individuals meeting the criteria will be given a

diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder with

three levels of severity based on degree of

support needed.

Diagnostic criteria include deficits in social

communication and social interaction; and

restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior,

interest or activities, which cause significant

impairments in daily functioning.

Eliminates pervasive developmental disorder

and its subcategories (autistic disorder, Retts

disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder,

Aspergers disorder, pervasive developmental

disorder-not otherwise specified [PDD-NOS]).

Rett syndrome, a genetic disorder, is not

included in DSM-5, although girls with Rett

syndrome often have ASD symptoms and may

be diagnosed with ASD if they meet the criteria.

Omits criterion related to delay in or lack of

development of spoken language. Rather, the

evaluator is to specify whether the ASD occurs

with or without accompanying language

impairment.

Changes the age of onset from prior to age 3

years in DSM-IV to symptoms present in the

early developmental period.

DSM-5 consolidated subcategories in ASD.

ASHA supported this change due to lack of

evidence for discrete categories.

ASHA recommended including disorders of

language content (semantics), form (phonology,

syntax) and use (pragmatics, social

communication) in the diagnostic criteria for

ASD. DSM-5 diagnostic criteria do not reflect

the significance of language content and form in

defining ASD. However, the severity specifiers

and diagnostic features capture language

deficits in more detail.

ASHA suggested that DSM-5 criteria indicate

that nonverbal communication behaviors vary

within and across cultures. Although the ASD

diagnostic criteria in DSM-5 do not mention

cultural variation, the diagnostic features, which

describe the criteria in greater detail, indicate

that nonverbal communication should be

assessed relative to cultural norms. Sections

detailing culture and gender-related diagnostic

issues also were added in DSM-5.

Under new DSM-5 criteria, individuals will

receive a diagnosis of ASD, rather than

previous subcategories. There is concern that

those who are higher functioning may not

receive an ASD diagnosis and may not get the

services they need.

Social (pragmatic) communication disorder is

a more appropriate diagnosis than ASD for a

client who has difficulties with social skills but

doesnt show restricted or repetitive patterns of

behavior. SLPs will be instrumental in making

this differential diagnosis.

Because the language component is

downplayed in the ASD criteria, SLPs will need

to advocate for the inclusion of language in

intervention plans for those with ASD.

SLPs will need to ensure that people with

ASD receive a comorbid diagnosis of language

disorder (a component of communication

disorders) when they meet the criteria for both

conditions.

There is a need to ensure that services arent

limited to those with higher severity levels.

The more descriptive and clear DSM-5

criteria for ASD may benefit children by

leading to earlier diagnosis and intervention.

Communication Disorders

Diagnostic categories for communication

disorders include Language Disorder,

Speech Sound Disorder, Childhood-Onset

Fluency Disorder (Stuttering), Social

(Pragmatic) Communication Disorder, and

Unspecified Communication Disorder. This

represents a change from the DSM-IV

categories of Expressive Language Disorder

and Mixed Receptive-Expressive Language

Disorder.

Language Disorder. The diagnostic criteria

for language disorder include persistent

difficulties in the acquisition and use of

language across modalities (i.e., spoken,

written, sign language, or other) due to deficits

in comprehension or production, language

abilities that are substantially and quantifiably

below age expectations.

Social (Pragmatic) Communication

Disorder. The diagnostic criteria for social

(pragmatic) communication disorder are

persistent difficulties in the social use of verbal

and nonverbal communication, which include

deficits in using communication for social

purposes , impairment in the ability to

change communication to match context or the

needs of the listener, difficulties following

rules for conversation and storytelling, and

difficulties understanding what is not explicitly

statedand nonliteral or ambiguous meaning of

language.

Speech Sound Disorder. The key diagnostic

criterion for speech sound disorder includes

persistent difficulty with speech sound

production that interferes with speech

intelligibility or prevents verbal communication

ASHA recommended including a statement that

a regional, social, or cultural or linguistic

variation (e.g., dialect) of language is not a

language disorder. DSM-5 indicates that

regional, social, or cultural/ethnic variations of

speech should be considered before making the

diagnosis. DSM-5 also states in the

introduction to this section that speech,

language, and communication assessments

must take into account the individuals cultural

and language context, particularly for

individuals growing up in bilingual

environments. Also indicated is that

standardized measures must be relevant for the

cultural and linguistic group.

ASHA did not recommend having a separate

category for social communication disorder.

ASHA indicated that difficulties in use of

language (e.g., impairments in discourse) were

already part of the criteria for a language

disorder. However, the criteria for Language

Disorder were reframed and were defined

primarily around vocabulary and grammar.

Social (Pragmatic) Communication Disorder

includes verbal and nonverbal communication

in a social context.

ASHA recommended indicating that speech

sound disorder may co-occur with a language

disorder. DSM-5 accepted this

recommendation.

ASHA asked that diagnostic criteria for

cluttering be added. However, cluttering is not

included.

ASHA recommended that motor speech

disorders, voice disorders and resonance

disorders not be included in DSM-5 because

It is essential that individuals with other

conditions, particularly ASD, specific learning

disorder, ADHD and intellectual disability, also

be diagnosed with a communication disorder

when they meet the diagnostic criteria for both.

SLPs will need to make sure to that individuals

with ASD be assessed for a language disorder.

Individuals with social (pragmatic)

communication disorder, however, cannot be

dually diagnosed as having ASD.

ASD must be ruled out before a diagnosis of

social (pragmatic) communication can be made.

SLPs will be key team players in making these

diagnoses.

Diagnosis of social communication, including

pragmatics, has been and will continue to be a

challenge, and we clearly need more research in

this area. Assessment needs to be contextually

based and involve multiple settings and

communication partners. Social communication

skills do not fit easily within a single

assessment tool. Multiple observations,

checklists, structured tasks, and assessment

measures are needed. Recognition of cultural

and linguistic variations is paramount,

particularly for this area of assessment.

Some may be concerned that individuals

diagnosed with social (pragmatic)

communication disorder may be given a lower

priority with respect to workload than

individuals diagnosed with ASD. However,

services should be based on need, not on

diagnostic labels or severity levels.

of messages.

Childhood-Onset Fluency Disorder

(Stuttering). The diagnostic criteria for

childhood-onset fluency disorder (stuttering) are

disturbances in the normal fluency and time

patterning of speech and the disturbance

causes anxiety about speaking.

The onset of symptoms for communication

disorders is in the early developmental

period. However, social communication

deficits may continue to unfold with increasing

social communication demands. Adult-onset

fluency disorders are not included in DSM-5.

they are physiological problems rather than

mental or developmental disorders. DSM-5

does not include these disorders.

ASHA suggested refraining from using

developmental in the description of

childhood-onset fluency disorder because this

disorder is not developmental in nature, but

rather is applicable to individuals whose

stuttering has an observed onset during

childhood. DSM-5 indicates that the onset of

symptoms is in the early developmental period

and indicates that childhood-onset fluency

disorder is also called developmental

stuttering, but does not use the term

developmental as a diagnostic criterion or in

the description of the diagnostic features.

Intellectual Disability (Intellectual Developmental Disorder)

Change in terminology from Mental

Retardation to Intellectual Disability

(Intellectual Developmental Disorder).

Diagnostic criteria include deficits in

intellectual functions confirmed by both

clinical assessment and individualized,

standardized intelligence testing and deficits

in adaptive functioning. This represents a

move away from a specific IQ level and

expands the role of clinical assessment.

Onset is in the developmental period. In

DSM-IV, onset was indicated as before 18

years.

DSM-IV had distinct classifications of mild,

ASHA supported the change from Mental

Retardation to Intellectual Disability.

ASHA agreed with the need for alignment

with the American Association of

Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

(AAIDD) terminology and other

professionals and consumers who use this

more contemporary terminology.

ASHA recommended the elimination of

classification by IQ and severity level.

ASHA recommended use of the AAIDD

definition, which characterizes intellectual

disability by significant limitations both in

intellectual functioning (reasoning,

learning, problem solving) and in adaptive

Individuals with intellectual disabilities

may have a co-occurring condition such as

communication disorder, specific learning

disorder, or ASD when all of the diagnostic

criteria are met. SLPs will play a pivotal

role in making these differential diagnoses.

SLPs will be critical members of a

diagnostic and intervention team to ensure

that individuals receive ongoing support,

AAC systems, and involvement of

communication partners.

More individuals may be diagnosed with

intellectual disability because the diagnosis

does not require a specific IQ score.

moderate, severe, and profound mental

retardation based on IQ level. DSM-5 has a

single category of intellectual disability rather

than divisions by severity level. There are

specifiers now for various levels of severity

that are defined by adaptive functioning

across conceptual, social, and practical

domains.

The category of Global Developmental

Delay may apply for children under the age

of 5 years when severity level cannot be

assessed reliably. Unspecified Intellectual

Disability (Intellectual Developmental

Disorder) is limited to individuals older than

5 years when assessment is difficult or

impossible due to associated sensory,

physical, or other conditions.

The need for assessment tools for intellectual

and adaptive functioning that are culturally

appropriate is mentioned in the section on

diagnostic features.

behaviors. (www.aaidd.org).

ASHA recommended including assessment

of support needs such as augmentative and

alternative communication systems (AAC)

and involvement of communication

partners. DSM-5 recognizes the need for

ongoing support to address limits in

adaptive functioning. The diagnostic

features indicate that standardized measures

should be used with knowledgeable

informants.

Major and Mild Neurocognitive Disorders

Dementia is no longer a separate diagnostic

category; replaced by major and mild

neurocognitive disorders (NCD).

Dementia as described in DSM-IV is

classified under major NCD.

Mild cognitive impairment can now be

diagnosed and coded under the new mild

NCD sub-category.

The term dementia can be used to reflect

ASHA supported the change of diagnostic

category from Delirium, Dementia,

Amnestic, and Other Geriatric Cognitive

Disorders to Neurocognitive Disorders

because it is broader in scope and includes

cognitive deficits related to traumatic brain

injury.

ASHA did not support the differentiation

between major and mild

neurocognitive because the differences

between the categories appear to be

May increase referrals of individuals with

mild NCD disorders for cognitive services.

Clinicians and consumers may be confused

when the severity markers are applied to a

major NCD. For example, it is now

possible to receive a diagnosis of a mild

major NCD.

etiological subtypes (e.g., Alzheimers

dementia).

Diagnostic criteria for different etiological

subtypes are either elaborated (vascular &

Alzheimers disease) or revised and

separately delineated (frontotemporal NCD,

Lewy bodies, traumatic brain injury (TBI),

Parkinsons disease, HIV infection,

Huntingtons disease, prion disease,

substance/medication-induced NCD, another

medical condition, multiple etiologies and

unspecified).

Cognitive domains (deficits in), which are the

basis of the NCD diagnosis, are clearly

specified.

arbitrary.

ASHA recommended that the severity

specifiers be excluded for neurocognitive

disorders since a diagnosis such as severe

mild NCD would be confusing. As per

these recommendations, the severity

specifiers for mild NCD have been

excluded. However, the severity markers of

mild, moderate and severe are included as

specifiers for major NCD.

ASHA did not support describing deficits in

mild NCD as insufficient to interfere with

independence. ASHAs recommended

revisions were accepted.

ASHA recommended retaining the explicit

description of symptoms of mild TBI

provided in DSM-IV, and adding

difficulty concentrating as a feature of

mild TBI. Both of these recommendations

were accepted.

Selective Mutism

Now classified as an anxiety disorder (rather

than Other Disorder of Infancy, Childhood ,

or Adolescence in DSM-IV)

No change in the diagnostic criteria.

ASHA did not make recommendations

pertaining to the diagnostic criteria for

selective mutism.

SLPs will continue to be involved as team

members in the diagnosis and treatment of

selective mutism.

Specific Learning Disorder

Characterized as difficulties learning and

using academic skills. Diagnostic criteria

include difficulty with word reading,

understanding the meaning of what is read,

word meaning, spelling, written expression,

ASHA expressed concern about the

omission of oral language as a diagnostic

criterion for specific learning disorder.

DSM-5 indicates that a specific learning

disorder is frequently, but not invariably

Omission of reference to oral language

significantly misrepresents the constellation

of learning disabilities. As a consequence,

individuals may be excluded from receiving

the services they need and research

number use and calculation, and

mathematical reasoning. Combines

diagnoses, which were separate in DSM-IV,

of reading disorder, disorder of written

expression, mathematics disorder, and

learning disorder not otherwise specified.

Determines academic performance through

standardized achievement measures and

comprehensive clinical assessment. Notes

that clinical synthesis should occur based

on the individuals developmental, medical,

family, and educational histories, school

reports, and psycho-educational assessment.

Affected academic skills must be

substantially and quantifiably below those

expected based on chronological age (or

average achievement that is sustainable only

by extraordinary high levels of effort or

support).

Deficits must cause significant interference

with academic or occupational performance,

or with activities of daily living.

Severity levels are specified separately for

impairments in reading, written expression,

and mathematics.

Does not include disorders of spoken

language (speaking and listening) as a

diagnostic criterion.

preceded, in preschool years, by delays in

attention, language or motor skills that may

persist and co-occur with specific learning

disorder.

ASHA argued against the use of

standardized measures as the sole basis for

diagnosis of specific learning disorder.

DSM-5 recognizes the need to include

multiple sources of data to make an

accurate diagnosis. ASHA supports the use,

when available, of culturally and

linguistically appropriate, age-appropriate,

and psychometrically sound standardized

measures as part of an assessment battery

in which assessments are conducted with

fidelity and repeated over time. Use of

inappropriate measures can lead to an

increase in false positives and false

negatives in diagnosing any disorder.

ASHA stressed the need to use culturally

and linguistically appropriate measures.

DSM-5 includes a section on culture-

related diagnostic issues for a specific

learning disorder. This section includes

assessment considerations for English

language learners and the need to consider

cultural and linguistic contextual factors for

assessment.

ASHA preferred the term specific learning

disability, well-established clinical and

research term, rather than specific learning

disorder. Disability addresses the impact of

a disorder and represents a lifelong

problem. However, DSM-5 recognizes that

a specific learning disorder can have

populations may be identified inaccurately.

SLPs will need to be vigilant about

ensuring that individuals with a specific

learning disorder, who also meet the

diagnostic criteria for a language disorder,

receive both diagnoses.

SLPs who are part of the diagnostic team

should emphasize that language can be in

any modality, such as spoken, manually

coded (e.g., signing, cued speech), or other

type of augmentative and alternative

communication system.

Because a specific learning disorder

comprises multiple disorders, it is

important that SLPs and other professionals

recognize that need for comprehensive

assessment and multiple intervention

strategies, which may change over time.

negative functional consequences across

the lifespan.

*Note: ASHA provided comments during the three public comment periods.

References and Resources

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fifth Edition.

Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Resources, www.dsm5.org

Highlights of Changes from DSM-IV-TR to DSM-5 http://www.dsm5.org/Documents/changes%20from%20dsm-iv-tr%20to%20dsm-5.pdf

Frequently Asked Questions on the DSM-5 http://www.dsm5.org/about/Pages/faq.aspx

Fact Sheets on Whats New http://www.dsm5.org/

You might also like

- The Dsm-5 Survival Guide: a Navigational Tool for Mental Health ProfessionalsFrom EverandThe Dsm-5 Survival Guide: a Navigational Tool for Mental Health ProfessionalsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- DSM 5 OverviewDocument78 pagesDSM 5 Overviewoyehello23No ratings yet

- ASWB EXAMINATION IN SOCIAL WORK [ASWB] (1 VOL.): Passbooks Study GuideFrom EverandASWB EXAMINATION IN SOCIAL WORK [ASWB] (1 VOL.): Passbooks Study GuideNo ratings yet

- Writing DSM 5 DiagnosisDocument2 pagesWriting DSM 5 Diagnosiscristina83% (6)

- LMSW Exam Prep Pocket Study Guide: Intervention Methods and TheoriesFrom EverandLMSW Exam Prep Pocket Study Guide: Intervention Methods and TheoriesNo ratings yet

- A Survival Guide to Understanding the DSM-5Document73 pagesA Survival Guide to Understanding the DSM-5Luke Bacon100% (2)

- Foundations of Clinical Psychiatry Fourth EditionFrom EverandFoundations of Clinical Psychiatry Fourth EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- DSM 5 EssentialsDocument8 pagesDSM 5 EssentialsAlyssa Gervacio100% (2)

- Psychotherapist'S Guide To Psychopharmacology: Second EditionFrom EverandPsychotherapist'S Guide To Psychopharmacology: Second EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (6)

- DSM 5 DiagnosesDocument1 pageDSM 5 DiagnosesGen Feliciano100% (4)

- Joel Paris-The Intelligent Clinician's Guide To The DSM-5®-Oxford University Press (2013)Document265 pagesJoel Paris-The Intelligent Clinician's Guide To The DSM-5®-Oxford University Press (2013)JC Barrientos100% (7)

- DSM 5 ChartDocument2 pagesDSM 5 ChartJanie VandeBerg93% (27)

- What's New With DSM 5? (Formerly Known As DSM V) : 1 Credit Continuing Education CourseDocument15 pagesWhat's New With DSM 5? (Formerly Known As DSM V) : 1 Credit Continuing Education CourseTodd Finnerty44% (9)

- DSM VDocument9 pagesDSM VAddie Espiritu100% (4)

- More Than Just Words and Numbers:: The Top 15 Fundamental Changes To The Dsm-5 & The Transition To Icd-10Document107 pagesMore Than Just Words and Numbers:: The Top 15 Fundamental Changes To The Dsm-5 & The Transition To Icd-10Hilma Harry'sNo ratings yet

- DSM-5 List of Mental DisordersDocument2 pagesDSM-5 List of Mental DisordersIqbal Baryar100% (1)

- DSM 5 SummaryDocument61 pagesDSM 5 Summaryroxxifoxxi87% (15)

- Case of JessicaDocument2 pagesCase of JessicaElaine Joyce PasiaNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Rating Scales-RRFINALDocument45 pagesPsychiatric Rating Scales-RRFINALnkivc100% (1)

- Mental Health NotesDocument21 pagesMental Health Notesbazahoor97% (33)

- DSM-5 Diagnosis Reference GuideDocument2 pagesDSM-5 Diagnosis Reference GuideDeAn White100% (1)

- Changes From Dsm-IV-tr To Dsm-5Document19 pagesChanges From Dsm-IV-tr To Dsm-5Sofia Cabezas Ordóñez100% (1)

- Misophonia assessment toolsDocument12 pagesMisophonia assessment toolsSoraia RomanelliNo ratings yet

- DSM 5 Update 2016Document33 pagesDSM 5 Update 2016Monica Putri Damayanti100% (1)

- DSM-5 Personality DisordersDocument2 pagesDSM-5 Personality DisordersIqbal BaryarNo ratings yet

- DSM 5 Cross Cutting Over ViewDocument9 pagesDSM 5 Cross Cutting Over Viewapi-4201886000% (1)

- Common Psychiatric MedicationsDocument1 pageCommon Psychiatric MedicationsDan Kiarie92% (12)

- Intellectual DisabilitiesDocument4 pagesIntellectual Disabilitieslevs rivers100% (1)

- DSM 5 Clinicalcases SoftDocument226 pagesDSM 5 Clinicalcases SoftSophie100% (5)

- Resident's Guide To Clinical PsychiatryDocument412 pagesResident's Guide To Clinical PsychiatryJP Rajendran88% (16)

- PSYCHIATRY Course NotesDocument43 pagesPSYCHIATRY Course NotesNisha PillaiNo ratings yet

- Psychiatry: Mental State ExaminationDocument3 pagesPsychiatry: Mental State ExaminationSok-Moi Chok100% (3)

- Charles Scott-DSM-5® and The Law - Changes and Challenges-Oxford University Press (2015) PDFDocument305 pagesCharles Scott-DSM-5® and The Law - Changes and Challenges-Oxford University Press (2015) PDFfpsearhiva personala100% (3)

- Clinical Psych NotesDocument9 pagesClinical Psych Notesky knmt100% (1)

- Psych CardsDocument10 pagesPsych CardsJennifer Rodriguez96% (23)

- DSM 5 - DSM 5Document7 pagesDSM 5 - DSM 5Roxana ClsNo ratings yet

- The Biopsychosocial Formulation Manual A Guide For Mental Health Professionals PDFDocument178 pagesThe Biopsychosocial Formulation Manual A Guide For Mental Health Professionals PDFLeidy Yiseth Cárdenas100% (4)

- PTSD Clinical Case ExampleDocument10 pagesPTSD Clinical Case Exampleapi-552282470No ratings yet

- DSM 5 CriteriaDocument6 pagesDSM 5 CriteriaCarmela ArcillaNo ratings yet

- DSM-5 Survival Guide Formatted FinalDocument73 pagesDSM-5 Survival Guide Formatted FinalrobajonesincNo ratings yet

- DSM-5 Insanely Simplified: Unlocking The Spectrums Within DSM-5 and ICD-10 - PsychiatryDocument5 pagesDSM-5 Insanely Simplified: Unlocking The Spectrums Within DSM-5 and ICD-10 - Psychiatrylucebycu0% (1)

- DSM 5 TR What's NewDocument2 pagesDSM 5 TR What's NewRafael Gaede Carrillo100% (1)

- DSM-5 LCA Case Formulation Rev.Document31 pagesDSM-5 LCA Case Formulation Rev.Khadeeja Rana100% (3)

- Screening For Personality Disorders Among PDFDocument14 pagesScreening For Personality Disorders Among PDFDrMartens AGNo ratings yet

- Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory TestDocument26 pagesMinnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory TestGicu BelicuNo ratings yet

- Antidepressant Comparison ChartDocument3 pagesAntidepressant Comparison Chartiggyputtty100% (29)

- Biopsychosocial Formulation PocketmodDocument1 pageBiopsychosocial Formulation Pocketmodluming7100% (1)

- Example Dap NoteDocument5 pagesExample Dap NoteLindsey Jo Townsend80% (5)

- 1001 Biopsychosocial Assessment (PIHP) (Handwritten)Document26 pages1001 Biopsychosocial Assessment (PIHP) (Handwritten)Sharon Price-James100% (3)

- The Mental Status Exam: A Systematic ApproachDocument35 pagesThe Mental Status Exam: A Systematic ApproachMohamad Faizul Abu HanifaNo ratings yet

- Notes On Mood DisordersDocument21 pagesNotes On Mood DisordersPrince Rener Velasco Pera67% (3)

- Behavioral Guide To Personality Disorders - (DSM-5) (2015) by Douglas H. RubenDocument275 pagesBehavioral Guide To Personality Disorders - (DSM-5) (2015) by Douglas H. RubenCristianBale100% (6)

- DSM5 Workshop PresentationsDocument185 pagesDSM5 Workshop PresentationsMichel Haddad100% (2)

- DSM 5 DiagnosingDocument107 pagesDSM 5 DiagnosingMichel Haddad100% (1)

- HTTP WWW - Nami.org Template - CFM Section Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) &template ContentManagement ContentDisplayDocument20 pagesHTTP WWW - Nami.org Template - CFM Section Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) &template ContentManagement ContentDisplayCorina MihaelaNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Clinical SkillsDocument376 pagesPsychiatric Clinical SkillsSamuel Agunbiade100% (5)

- Case FormulationDocument22 pagesCase FormulationELvine Gunawan100% (5)

- The Master Disorder Document SPR 2015Document6 pagesThe Master Disorder Document SPR 2015api-261267976100% (1)

- Suicide Risk Assessment Summary.08Document1 pageSuicide Risk Assessment Summary.08Pintiliciuc-aga MihaiNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Assessment ToolDocument53 pagesPsychiatric Assessment ToolLori100% (4)

- Utility of BAI Factors in Screening Anxiety DisordersDocument15 pagesUtility of BAI Factors in Screening Anxiety DisordersMilos Beba Ristic100% (1)

- Management Guidelines For Anxiety Disorders in Children and AdolescentsDocument23 pagesManagement Guidelines For Anxiety Disorders in Children and AdolescentsHari HaranNo ratings yet

- Brief Psychiatric Rating ScaleDocument1 pageBrief Psychiatric Rating ScalesilmarestuNo ratings yet

- 21 - Smith2014Document33 pages21 - Smith2014stupidshitNo ratings yet

- Psychological Disorders Chapter 13: Defining and Diagnosing Mental Disorders/TITLEDocument34 pagesPsychological Disorders Chapter 13: Defining and Diagnosing Mental Disorders/TITLEannaNo ratings yet

- Psych 1 Phobia ProjectDocument3 pagesPsych 1 Phobia ProjectalexlaneNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Psychodynamic Psychotherapies - An Update (2015) PDFDocument14 pagesThe Effectiveness of Psychodynamic Psychotherapies - An Update (2015) PDFmysticmdNo ratings yet

- A Different Approach To Rising Rates of ADHD DiagnosisDocument1 pageA Different Approach To Rising Rates of ADHD DiagnosisPaul AsturbiarisNo ratings yet

- Child Depression Inventory Cdi InterpretationDocument2 pagesChild Depression Inventory Cdi InterpretationGerlinde M Schmidt75% (4)

- Ab Psych Exam by Sir ThanksDocument15 pagesAb Psych Exam by Sir ThanksSteffiNo ratings yet

- Borderline Personality DisorderDocument368 pagesBorderline Personality Disordercarlesavila224678% (9)

- Child and Adolescent DisorderDocument38 pagesChild and Adolescent DisorderZeref KakarotNo ratings yet

- Letter For Wayne McGuinness' Ride For Mental HealthDocument2 pagesLetter For Wayne McGuinness' Ride For Mental Healthscribd-jNo ratings yet

- Libro The Oxford Handbook of Depression and Comorbidity PDFDocument673 pagesLibro The Oxford Handbook of Depression and Comorbidity PDFToñitoo H. Skelter100% (2)

- Mania & ADHDDocument47 pagesMania & ADHDbabarsaggu100% (1)

- CBT Reading ListDocument6 pagesCBT Reading ListrzeczywistoscgryzieNo ratings yet

- You Probably Have AdhdDocument3 pagesYou Probably Have AdhdNur Amaleena GafarNo ratings yet

- Kleptomania and HomoeopathyDocument7 pagesKleptomania and HomoeopathyDr. Rajneesh Kumar Sharma MD HomNo ratings yet

- Catatonia: FeaturesDocument6 pagesCatatonia: FeaturesfirehuNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Foundations of Mental Health Care 3rd Edition Morrison ValfreDocument11 pagesTest Bank For Foundations of Mental Health Care 3rd Edition Morrison ValfreAnthonyRiveraqion100% (43)

- Ocd in dsm-5 2014Document15 pagesOcd in dsm-5 2014Dilan RasyidNo ratings yet

- Delusion and HallucinationDocument4 pagesDelusion and HallucinationRiezky FebriyantiNo ratings yet

- Psychiatry SamsonDocument12 pagesPsychiatry Samsonamina100% (1)

- Parental Substance AbuseDocument8 pagesParental Substance Abuseapi-458338612No ratings yet

- Child Psychiatry - Introduction PDFDocument7 pagesChild Psychiatry - Introduction PDFRafli Nur FebriNo ratings yet

- Don'T Hide Behind Happiness, Live in ItDocument3 pagesDon'T Hide Behind Happiness, Live in ItChacha D. LoñozaNo ratings yet

- Social Anxiety Disorder PDFDocument14 pagesSocial Anxiety Disorder PDFhamoNo ratings yet

- Anxiety DisordersDocument18 pagesAnxiety DisordersAzahed ArturoNo ratings yet

- Adhd - David JesselsonDocument12 pagesAdhd - David Jesselsonapi-311051259100% (1)

- Psychiatry 1 Dr. Anastasia Ratnawati Biromo, SPKJ - Identifying Anxiety and Somatization and Its Treatment in General PracticeDocument23 pagesPsychiatry 1 Dr. Anastasia Ratnawati Biromo, SPKJ - Identifying Anxiety and Somatization and Its Treatment in General PracticeThomas KweeNo ratings yet

![ASWB EXAMINATION IN SOCIAL WORK [ASWB] (1 VOL.): Passbooks Study Guide](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/402068986/149x198/afec08b5ad/1617230405?v=1)