Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Vomiting in Cancer and Mecanism

Uploaded by

Venansius Ratno KurniawanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Vomiting in Cancer and Mecanism

Uploaded by

Venansius Ratno KurniawanCopyright:

Available Formats

Nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer

Dylan G. Harris

*

Department of Palliative Care, Cwm Taf Health Board, Merthyr Tydfil, South Wales, UK

Nausea and vomiting are distinct symptoms, commonly occurring together but

which should be assessed separately. Both are prevalent in patients with advanced

cancer. Data are taken from The Cochrane Library (2010) and Ovid MEDLINE

(19662010). Most current guidelines advocate an aetiology-based approach to

the management of nausea and vomiting. Choice of anti-emetic is based on a

clinical assessment of the likely pathophysiological component of the emetogenic

pathway that is being triggered and selecting an anti-emetic drug that blocks the

key receptors involved. Some authors propose a more empirical approach. The

limited available evidence would suggest that both an empirical or aetiology-

based approach may have similar overall efcacy. There are no published studies

directly comparing the two. Standardized assessment and outcome tools are

needed to enable well-designed studies to establish efcacy for conventional

agents and also compare efcacy with the newer, more expensive ones.

Keywords: nausea/vomiting/cancer/emesis

Accepted: August 22, 2010

Introduction

Nausea and vomiting is common in advanced disease. The prevalence

in patients with advanced cancer is up to 70% and up to 50% in non-

malignant advanced disease such as heart failure, chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease and renal failure.

18

Nausea and vomiting appear

to increase in prevalence as disease progresses.

9

Nausea may be defined as an unpleasant feeling of the need to vomit,

often accompanied by autonomic symptoms such as pallor, cold sweat,

salivation, tachycardia and diarrhoea,

5,7,10

whereas vomiting is the for-

ceful expulsion of gastric contents through the mouth through a

complex reflex involving coordinated activities of the gastrointestinal

tract, diaphragm and abdominal muscles.

5,7,10

Although the two symptoms are often clinically associated, they

should be assessed separately.

1,5

Patients may use the term vomiting

to describe a variety of problems including expectoration and regurgi-

tation and a careful history is therefore important.

British Medical Bulletin 2010; 96: 175185

DOI:10.1093/bmb/ldq031

& The Author 2010. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

For permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions@oxfordjournals.org

*Correspondence address.

Palliative Medicine,

Prince Charles Hospital,

Merthyr Tydfil CF47 9DT,

UK. E-mail: dgharris@

doctors.org.uk

Published Online September 30, 2010

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

p

r

i

l

1

1

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

b

m

b

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

Physiology of the emetogenic pathway

The current approach to managing nausea and vomiting in advanced

cancer is largely based on physiological principles, an understanding of

which is therefore required to appreciate the rationale behind current

recommendations.

The afferent and efferent reflexes that result in nausea and vomiting

are thought to be integrated by two distinct centres at brainstem level

(Fig. 1):

(i) The chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) is located in the floor of the

fourth ventricle and is outside the bloodbrain barrier.

5,1012

Rather than

being a specific anatomical area, the CTZ is likely to exist as interconnect-

ing neural networks penetrating into the nucleus of the tractus solitarius.

12

The CTZ is stimulated by chemicals in cerebrospinal fluid and blood as

well as vestibular and vagal afferents.

1,5,10

It contains receptors for dopa-

mine (D2), serotonin (5HT3), acetylcholine (ACH) and opioids (MU2).

5

(ii) The vomiting centre (VC) is situated in the medulla oblongata and has a

bloodbrain barrier.

5,10

The VC, again a diffuse interconnecting neural

network rather than a distinct anatomical structure, receives afferent input

from the CTZ; the glossopharyngeal and splanchnic nerves; cerebral

cortex; thalamus; hypothalamus; and, the vagus nerve through the stimu-

lation of stretch of mechanoreceptors and activation of 5HT3 receptors in

the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

1

Fig. 1 The emetogenic pathway.

1,7,9,10,13

D. G. Harris

176 British Medical Bulletin 2010;96

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

p

r

i

l

1

1

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

b

m

b

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

The end result of the above pathways is the vomiting reflex, which

results in peristalsis of the upper GI tract, relaxation of the pylorus and

oesophagus and contraction of the intercostal muscles, diaphragm and

abdominal wall culminating in forced expulsion of gastric contents

through the mouth past a closed glottis. It is postulated that stimuli

insufficient to trigger vomiting may nevertheless produce nausea

through the same pathway.

1

At least 17 potential neurotransmitters or receptors have been ident-

ified in the CTZ and nucleus of the tractus solitariu.

8,13

Numerous

receptors have been identified at the CTZ and VC and many more may

exist (Fig. 1). Furthermore, there is some evidence that the efficacy of

an anti-emetic drug is directly related to its binding affinity for a

specific receptor.

14,15

There are now five known dopamine receptors (D1D5); historically

only D2 receptors were associated with the emetogenic pathway (antag-

onized by drugs such as haloperidol and metoclopramide) but D3 recep-

tors are also now felt to be involved on the basis of animal studies.

12

There are several groups of serotonin receptors of which 5HT3 has

had the most interest since metoclopramide was found to be a weak

5HT3 receptor antagonist. Selective 5HT3 receptor antagonists were

subsequently developed with ondansetron being one of the first drugs

in this category.

8,12

Other important receptors involved in the emetogenic pathway

include histamine, ACH, endorphins, gamma-aminobutyric acid and

cannabinoids.

12

In contrast to other anti-emetics, cannabinoids appear

to exert their effect by agonism at the cannabinoid (CB1) receptor.

12

The above pathophysiological process forms the basis of most current

guidelines: choice of anti-emetic is based on a clinical assessment of

which component of the emetogenic pathway is being triggered, which

receptors are involved and selecting an anti-emetic drug which there-

fore blocks those specific receptors (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

1,4

Clinical application

On the above basis, current recommendations advocate a structured

approach to choosing an anti-emetic in clinical practice.

1,3,4,7,911,13

(i) Clinical assessment to ascertain the most likely cause of the symptoms

(history, examination and appropriate investigations).

(ii) Identify the pathway by which each cause triggers the emetogenic

pathway and vomiting reflex.

(iii) Treat any reversible cause, e.g. hypercalcaemia.

Nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer

British Medical Bulletin 2010;96 177

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

p

r

i

l

1

1

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

b

m

b

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

(iv) Identify the likely neurotransmitter receptor(s) involved in each

pathway.

(v) Choose an anti-emetic that antagonizes the receptor(s) identified.

(vi) Give each anti-emetic by a route that ensures absorption (therefore unli-

kely to be oral in the frequently vomiting patient).

(vii) Give regularly, titrate the dose and reassess the patients symptoms.

(viii) Use non-pharmacological measures in combination with the selected

pharmacological agents.

Common mechanisms in advanced cancer are delayed gastric emptying

( prevalence of 3544% in case series

3,16

), chemical ( prevalence of

3033% in case series

3,16

) and gastrointestinal causes such as bowel

obstruction and constipation ( prevalence of 3132% in case

series

3,16

).

Clearly the effectiveness of aetiology-based guidelines depends on the

ability to identify the underlying cause of the nausea/vomiting. It is

suggested that this can be done clinically in 90% of cases.

4,16,17

This

figure can obviously only be an estimate as there is no gold standard

diagnostic test for nauseavomiting aetiology against which it can be

tested. Furthermore, many patients (up to 25% in some studies) may

have multiple causes.

3,16,18

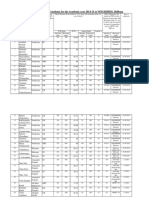

Table 1 Aetiology-based classication of nausea and vomiting.

710,16

Aetiology Examples Appropriate rst-line antiemetic and

typical starting dose

Chemical Drugs, e.g. opioids, digoxin, antibiotics,

cytotoxics; toxins, e.g. ischaemic bowel,

infection; metabolic, e.g. hypercalcaemia

Haloperidol, 1.5 mg bd or 5 mg

subcutaneously over 24 h

Delayed gastric

emptying

Drugs, e.g. opioids, tricyclic

antidepressants; ascites

Metoclopramide, 10 mg qds or 40 mg

subcutaneously over 24 h

Hepatomegaly; autonomic dysfunction Domperidone, 10 mg qds

Gastrointestinal Bowel obstruction Hyoscine butylbromide, 60 mg

subcutaneously over 24 h or cyclizine,

150 mg subcutaneously over 24 h.

Consider adding haloperidol and/or

dexamethasone. If partial obstruction

and/or abdominal colic consider

metoclopramide instead

Radiation colitis, post-chemotherapy Ondansetron, 8 mg bd-tds

Cranial Raised intracranial pressure, e.g. from

tumour or intracranial bleed; meningeal

inltration

Cyclizine, 50 mg tds or 150 mg

subcutaneously over 24 h (in conjunction

with dexamethasone)

Vestibular Drugs, e.g. opioids; vestibular neuritis

and labyrinthitis

Cyclizine, 50 mg tds or 150 mg

subcutaneously over 24 h

Cortical Anxiety, anticipatory nausea, pain Benzodiazepines, e.g. oral lorazepam,

0.5 mg as required

Bd, twice daily; tds, three times daily; qds, four times daily.

D. G. Harris

178 British Medical Bulletin 2010;96

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

p

r

i

l

1

1

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

b

m

b

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

Specific anti-emetics

Metoclopramide

Metoclopramide is a pro-kinetic anti-emetic (through agonism of

5HT4 receptors, antagonism of peripheral D2 receptors and possible

antagonism of 5HT3 receptors) and therefore useful in nausea and

vomiting related to gastric stasis.

3,7

There are a few small placebo-

controlled trials to support its efficacy.

4

Pro-kinetic agents which act

through 5HT4 receptors require ACH as a mediator at the myenteric

plexus and so are, in theory, antagonized by anticholingeric medication

(cyclizine may potentially therefore antagonize the pro-kinetic effect of

metoclopramide).

5,7

Domperidone is an alternative pro-kinetic to meto-

clopramide: it does not cross the blood-brain barrier and extrapyrami-

dal side effects are therefore less likely.

7

Haloperidol

Haloperidol is an anti-emetic principally acting in the area postrema.

3

It is a very potent D2 antagonist.

1

It is widely used in palliative care,

usually in the context of chemical causes of nausea and vomiting.

19

A

systematic review of its efficacy in the management of nausea and

vomiting found that evidence of use is limited to case reports and case

series with no controlled studies.

19

Consensus-based recommendations

advocate use in chemical or metabolic causes of nausea and

vomiting.

6,7

Cyclizine

Cyclizine is classified as an H1-antihistaminic anticholinergic

anti-emetic and principally acts by decreasing excitability of the inner

ear labyrinth and blocking conduction in the vestibularcerebellar path-

ways as well as acting directly at the vomiting centre in the brain-

stem.

3,9

It is particularly advocated for nausea and vomiting where the

underlying aetiology is felt to be increased intracranial pressure, motion

sickness, pharyngeal stimulation or mechanical bowel obstruction.

5,20

Current recommendations for use are largely based on consensus

(based on clinical experience).

9

As mentioned above, pro-kinetic agents

such as metoclopramide are potentially antagonized by anticholinergic

medication such as cyclizine and should not in theory be used together.

Levomepromazine

Levomepromazine is a phenothiazine which antagonizes 5HT2, hista-

mine, alpha-adrenergic receptors, D2 and muscarinic cholinergic

Nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer

British Medical Bulletin 2010;96 179

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

p

r

i

l

1

1

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

b

m

b

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

receptors.

7

It is a broad-spectrum anti-emetic often used where first-

line options have failed, particularly for nausea and vomiting of mul-

tiple or indeterminate cause.

13,21,22

There are no randomized con-

trolled trials to support its use in this context but there is some

evidence from open label studies.

6,22

Typical starting doses are 6.25 mg

once daily. Drowsiness can be the main dose limiting side effect.

21

Steroids

Steroids are used as a prophylactic anti-emetic for chemotherapy and

may have a wider adjuvant role in the management of nausea and

vomiting.

5

In the context of chemotherapy, studies have demonstrated

that dexamethasone improves the effect of other anti-emetics (metoclo-

pramide and more recently 5HT3 and NK1 receptor antagonists) in

preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

6,12

It has also

been shown to have a beneficial effect over placebo when used alone in

this context.

6

Dexamethasone (and possibly other corticosteroids) poss-

ibly act by reducing the permeability of the area postrema (where the

chemoreceptor trigger zone is located) and the bloodbrain barrier to

emetogenic substances.

7,21

Alternatively, its action may also relate to

depleting the inhibitory amine gamma-aminobutyric acid.

7,13

In symp-

tomatic bowel obstruction there is some evidence that corticosteroids

(e.g. 616 mg daily) may help resolve the obstruction with a number

needed to treat of six (but confidence interval 3 to infinity).

13,23

There

is some anecdotal evidence of benefit in nausea due to other causes in

terminal cancer (e.g. liver metastases).

7,13

Dexamethasone has a half-

life of up to 36 h which allows once-daily dosing.

5

Benzodiazepines

Anticipatory nausea and vomiting can be a learned response, e.g. fol-

lowing previous chemotherapy, but can also occur without prior

specific experiences depending on patient emotional distress and expec-

tations of the patient. Benzodiazepines have been documented to help

in adult patients in combination with psychological techniques.

24

5HT3 receptor antagonists

5HT3 receptor antagonists, e.g. ondansetron, granisetron, tropisetron,

dolasetron and palonosetron. 5HT3 receptors are implicated in the

emetogenic pathway in relation to massive release of 5HT from entero-

chromaffin cells in the bowel wall, immediately following

D. G. Harris

180 British Medical Bulletin 2010;96

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

p

r

i

l

1

1

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

b

m

b

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

chemotherapy for example (and block the amplifying effect of 5HT on

the vagal nerve).

9,10

Serotonin antagonists appear to exert their

anti-emetic effect via 5HT3 receptors both peripherally (enterochro-

maffin cells of the enteric nervous system) and centrally (nucleus

tractus solitaries and CTZ).

7

There is good evidence of efficacy in redu-

cing acute vomiting in patients receiving chemotherapy compared with

metoclopramide-based regimes ( particularly cisplatin-based chemother-

apy).

68

Previously there has been limited use in palliative care practice

outside the context of chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting and

concern about side effects, particularly constipation. There is some

argument, and a small amount of evidence, that these agents may be at

least as effective, or possibly even more effective, than anti-emetics tra-

ditionally used.

4,6,25,26

Current consensus guidelines advocates use for

chemical causes of nausea and vomiting refractory to haloperidol and

levomepromazine or when clinically it is felt that the cause of the

symptoms may relate to massive release of 5HT/serotonin from entero-

chromaffin cells, e.g. bowel obstruction and renal failure, as well as the

more recognized indications related to chemotherapy and

radiotherapy.

7,9

Olanzapine

Olanzapine is an atypical antipsychotic agent which blocks multiple

receptors including dopaminergic (D1D4), serotonergic (5HT2,

5HT3), histaminic (H1) and muscarinic.

7,9,12

This mode of action at

multiple receptors has therefore led to its experimental use as a second-

line anti-emetic in patients with refractory nausea.

18,27

Small uncon-

trolled studies have shown efficacy in this context.

18,27

Substance P antagonists (NK1 receptor antagonists)

Substance P is a neuropeptide found in the gut and central nervous

system and may induce nausea by binding the specific neuroreceptor

neurokinin1 (NK1). Several NK1 receptor antagonists have been

developed in the context of chemotherapy-induced nausea and

vomiting and post-operative nausea and vomiting.

5,8,28

Aprepitant

does not appear to be superior to ondansetron or granisetron in the

context of chemotherapy-induced vomiting (and to a lesser extent

nausea) but may increase their efficacy when used together with

dexamethasone.

8,12,13,20

Nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer

British Medical Bulletin 2010;96 181

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

p

r

i

l

1

1

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

b

m

b

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

Cannabinoids

Initially reports of a lower incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea

and vomiting amongst marijuana smokers led to exploration of canna-

binoids in the treatment of nausea and vomiting.

13

A brainstem canna-

binoid receptor has now been identified but as some of the anti-emetic

effects of synthetic cannabinoids are reversed by naloxone part of their

action may be at the opioid mu receptor.

13

A systematic review found

that the cannabinoids oral nabilone, oral dronabinol and intramuscular

levonantradol were more effective in reducing nausea and vomiting in

patients receiving chemotherapy than prochlorperazine, metoclopra-

mide, chlorpromazine, haloperidol, domperidone and alizapride.

20

They were however also associated with significant greater side effects

such as sedation, euphoria, dizziness, depression, hallucinations and

paranoia and a significantly higher patient withdrawal rate from

studies because of adverse effects.

20

As yet cannabinoids are not widely

used in this context in clinical practice, particularly as they often

appear to be associated with a high burden of side effects.

9,20

Non-pharmacological strategies

Non-pharmacological strategies are very important in the overall man-

agement of the patient. Examples include avoiding food with strong

tastes and smells; small but frequent meals; control of malodour from

wounds or ulcers, behavioural approaches (e.g. distraction, relaxation)

and acupuncture/acupressure.

7,8,10,11,13

There are positive Cochrane

reviews for acupuncture in the prevention of post-operative nausea and

vomiting

29

and chemotherapy-induced nausea.

21

Evidence base

A previous systematic review of the efficacy of anti-emetics in advanced

cancer found 21 appropriate published studies, which included two sys-

tematic reviews, seven randomized controlled trials and 12 uncon-

trolled studies.

4

A more recent systematic review of nausea and

vomiting in people with cancer and other chronic diseases found nine

studies that met the inclusion criteria.

6

Difficulties encountered in the

quality of these studies included small sample sizes; high attrition rates;

difficulty controlling for confounding variables ( patients with

advanced cancer are a very heterogeneous population); and, differing

outcome measures. These problems in methodology are common in

studies in palliative care.

30

D. G. Harris

182 British Medical Bulletin 2010;96

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

p

r

i

l

1

1

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

b

m

b

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

Evidence for individual anti-emetics is weak or non-existent.

4,8,19

However, little or no evidence does not mean they are ineffective:

absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

31

There are some

small placebo-controlled trials for some anti-emetics such as metoclo-

pramide.

6,32,33

A systematic review of the efficacy of haloperidol was

unable to find enough studies of sufficient quality to draw any specific

conclusions but it is advocated by consensus-based guidelines.

6,19

There is however a greater evidence base for treatment-related causes

of nausea and vomiting (radiotherapy and chemotherapy).

6

The latter

seems to be an area that has attracted more interest from the pharma-

ceutical industry and hence drug development (such as the 5HT3

antagonists).

Whilst the above aetiology-based approach to treating nausea and

vomiting is widely endorsed in palliative care guidelines it should be

noted that there is limited evidence to support the recommendations

(through a paucity of evidence rather than negative studies). In practice

it may sometimes be difficult to clinically ascertain the specific emeto-

genic pathway and therefore receptors involved.

The few studies and retrospective audits that have been conducted

have shown generally favourable outcomes through use of the above

approach with improvement in nausea in 5682% of patients and

vomiting in 8493%.

3,13,16,17

These studies have largely been uncon-

trolled, and the few randomized controlled studies that have been

performed have shown lower response rates. Of note, similar response

rates have been found when an empirical drug selection method has

been used.

13,16,17,25,3235

There has been no direct comparison

between the two approaches.

11

Conclusion

The aetiological-based approach to choice of anti-emetic is a useful

overall framework and remains the recommended practice in most

current guidelines. As with many areas of palliative care, the lack of

evidence for current practice is due to an absence of evidence rather

than evidence of absence (i.e. lack of robust clinical studies rather than

a collection of negative ones).

However, considering the multifactorial nature of nausea and vomit-

ing in many patients with advanced cancer; the multidimensional

aspects to nausea and vomiting (with anxiety and other psychological

factors playing an important role); and, the fact that many anti-emetic

drugs are known to affect multiple receptors, it is important to think

outside a mono-mechanistic treatment approach when facing a patient

with nausea and vomiting.

Nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer

British Medical Bulletin 2010;96 183

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

p

r

i

l

1

1

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

b

m

b

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

Future research in this area should include randomized controlled

trials of the empirical versus aetiology-based approaches, as well as

direct comparisons of the newer anti-emetic agents with those

historically used in a wider context than trials of chemotherapy-

induced emesis alone. On-going basic science research to enhance our

understanding of the neurophysiology of the emetogenic pathway is

also fundamental to identify new potential mechanisms of anti-emetic

drug action.

References

1 Mannix KA. Palliation of nausea and vomiting. CME Cancer Med 2002;1:1822.

2 Solano JP, Gomes B, Higginson I. A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced

cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease. J Pain

Symptom Manage 2006;31:5869.

3 Stephenson J, Davies A. An assessment of aetiology-based guidelines for the management

of nausea and vomiting in patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer

2006;14:34853.

4 Glare P, Pereira G, Kristjanson LJ et al. Systematic review of the efficacy of antiemetics in the

treatment of nausea in patients with far-advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer

2004;12:43240.

5 Davis MP, Walsh D. Treatment of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer. Support Care

Cancer 2000;8:44452.

6 Keeley PW. Nausea and vomiting in people with cancer and other chronic diseases. Clin Evid

(Online) 2009; January 13. pii:2406. http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/evidence/

background/2406.html. (6 September 2010, date last accessed).

7 Glare PA, Dunwoodie D, Clark K et al. Treatment of nausea and vomiting in terminally ill

cancer patients. Drugs 2008;68:257590.

8 Naeim A, Dy SM, Lorenz KA et al. Evidence-based recommendations for cancer nausea and

vomiting. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:390310.

9 Twycross R, Wilcock A. Palliative Care Formulary 3. 3rd edn. Nottingham:

Palliativedrugs.com Limited, 2007.

10 Twycross R, Back I. Nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer. Eur J Palliative Care

1998;5:3944.

11 Wood GJ, Shega JW, Lynch B et al. Management of intractable nausea and vomiting in

patients at the end of life: I was feeling nauseous all of the time . . . nothing was working.

JAMA 2007;298:1196207.

12 Herrstedt J. Antiemetics: an update and the MASCC guidelines applied in clinical practice.

Nat Clin Pract Oncol 2008;5:3243.

13 Mannix KA. Palliation of nausea and vomiting. In: Doyle D, Hanks G, Gherny N, Calman K

(eds). Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine, 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

2005,45968.

14 Peroutka SJ, Snyder SH. Anti-emetic: neurotransmitter binding predicts therapeutic actions.

Lancet 1982;319:6589.

15 Ison PJ, Peroutka SJ. Neurotransmitter receptor binding studies predict anti-emetic efficacy

and side effects. Cancer Treat Reports 1986;70:63741.

16 Bentley A, Boyd K. Use of clinical pictures in the management of nausea and vomiting: a pro-

spective audit. Palliat Med 2001;15:24753.

17 Lichter I. Results of antiemetic management in terminal illness. J Palliat Care 1993;9:1921.

18 Srivastava M, Brito-Dellan N, Davis MP et al. Olanzapine as an antiemetic in refractory

nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003;25:57882.

D. G. Harris

184 British Medical Bulletin 2010;96

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

p

r

i

l

1

1

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

b

m

b

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

19 Critchley P, Plach N, Grantham M et al. Efficacy of haloperidol in the treatment of nausea

and vomiting in the palliative patient: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage

2001;22:6314.

20 Tramer MR, Carroll D, Campbell FA et al. Cannabinoids for control of chemotherapy

induced nausea and vomiting: quantitative systematic review. BMJ 2001;323:1621.

21 Ezzo J, Richardson MA, Vickers A et al. Acupuncture-point stimulation for chemotherapy-

induced nausea or vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;2:CD002285. DOI: 10.1002/

14651858.CD002285.pub2.

22 Eisenchlas JH, Garrigue N, Junin M et al. Low-dose levomepromazine in refractory emesis in

advanced cancer patients: an open-label study. Palliat Med 2005;19:715.

23 Feuer DJ, Broadley KE. Corticosteroids for the resolution of malignant bowel obstruction in

advanced gynaecological and gastrointestinal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2000;2:CD001219.

24 Aapro MS, Molassiotis A, Olver I. Anticipatory nausea and vomiting. Support Care Cancer

2005;13:11721.

25 Mystakidou K, Befon S, Liossi C et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of tropisetron,

metoclopramide, and chlorpromazine in the treatment of emesis associated with far advanced

cancer. Cancer 1998;83:121423.

26 Bartlett N, Koczwara B. Control of nausea and vomiting after chemotherapy: what is the

evidence? Intern Med J 2002;32:4017.

27 Jackson WC, Tavernier L. Olanzapine for intractable nausea in palliative care patients.

J Palliat Med 2003;6:2515.

28 Abbrederis K, Lorenzen S, Rothling N et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting

in the treatment of gastrointestinal tumors and secondary prophylaxis with aprepitant.

Onkologie 2009;32:304.

29 Lee A, Fan LTY. Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point P6 for preventing postoperative

nausea and vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;2:CD003281. DOI: 10.1002/

14651858.CD003281.pub3.

30 Jordhoy MS, Kaasa S, Fayers P et al. Challenges in palliative care research; recruitment, attri-

tion and compliance: experience from a randomized controlled trial. Palliat Med

1999;13:299310.

31 Sagar C. Evidence of absence. http//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evidence_of_absence. (6 Septem-

ber 2010, date last accessed).

32 Bruera E, Belzile M, Neumann C et al. A double-blind, crossover study of controlled-release

metoclopramide and placebo for the chronic nausea and dyspepsia of advanced cancer.

J Pain Symptom Manage 2000;19:42735.

33 Hardy J, Daly S, McQuade B et al. A double-blind, randomised, parallel group, multina-

tional, multicentre study comparing a single dose of ondansetron 24 mg p.o. with placebo

and metoclopramide 10 mg t.d.s. p.o. in the treatment of opioid-induced nausea and emesis

in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2002;10:2316.

34 Bruera ED, MacEachern TJ, Spachynski KA et al. Comparison of the efficacy, safety, and

pharmacokinetics of controlled release and immediate release metoclopramide for the man-

agement of chronic nausea in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer 1994;74:320411.

35 Wilson J, Plourde JY, Marshall D et al. Long-term safety and clinical effectiveness of

controlled-release metoclopramide in cancer-associated dyspepsia syndrome: a multicentre

evaluation. J Palliat Care 2002;18:8491.

Nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer

British Medical Bulletin 2010;96 185

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

p

r

i

l

1

1

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

b

m

b

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

You might also like

- Role of Transcranial Approaches in The Treatment of Sellar and Suprasellar LesionsDocument28 pagesRole of Transcranial Approaches in The Treatment of Sellar and Suprasellar LesionsVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- ARTICULODocument4 pagesARTICULOALFREDO JUNIOR LEON ALEJONo ratings yet

- Protective Dural Flap For Bone Drilling at The Paraclinoid Region and Porus AcusticusDocument3 pagesProtective Dural Flap For Bone Drilling at The Paraclinoid Region and Porus AcusticusVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Arterial Gas Embolism in A Professional Diver With A Persistent Foramen OvaleDocument3 pagesCerebral Arterial Gas Embolism in A Professional Diver With A Persistent Foramen OvaleVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Bubble-Induced Platelet Aggregation in A Rat Model of Decompression SicknessDocument5 pagesBubble-Induced Platelet Aggregation in A Rat Model of Decompression SicknessVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Immersive Surgical Anatomy of The Pterional ApproachDocument25 pagesImmersive Surgical Anatomy of The Pterional ApproachVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Biomolecules 10 00389 v2Document19 pagesBiomolecules 10 00389 v2Venansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- AboutHydrocephalus-A Book For Families Dec08Document40 pagesAboutHydrocephalus-A Book For Families Dec08rudy.langeNo ratings yet

- Definitions of Intracranial Aneurysm Size and Morphology - A Call For StandardizationDocument7 pagesDefinitions of Intracranial Aneurysm Size and Morphology - A Call For StandardizationVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Corticotropinoma (Cushing's Disease)Document2 pagesCorticotropinoma (Cushing's Disease)Venansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Altitude Illness - Risk Factors, Prevention, Presentation, and TreatmentDocument8 pagesAltitude Illness - Risk Factors, Prevention, Presentation, and TreatmentVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Problems in DiversDocument2 pagesCardiovascular Problems in DiversVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Risk of Neurological Decompression Sickness in The Diver With A Right-To-Left Shunt - Literature Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument5 pagesRisk of Neurological Decompression Sickness in The Diver With A Right-To-Left Shunt - Literature Review and Meta-AnalysisVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Arterial Gas Embolism and DCSDocument6 pagesArterial Gas Embolism and DCSVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Parameter in A Mixed-Sex Swine Study of Severe Dcs Sickness Treated With The Emulsified Perfluorocarbon OxycyteDocument9 pagesCardiovascular Parameter in A Mixed-Sex Swine Study of Severe Dcs Sickness Treated With The Emulsified Perfluorocarbon OxycyteVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Pathogenesis of Dengue Viral InfectionsDocument7 pagesPathogenesis of Dengue Viral InfectionsVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Biophysical Basis For Inner Ear Decompression SicknessDocument6 pagesBiophysical Basis For Inner Ear Decompression SicknessVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- An Autopsy Case of Decompression Sickness - Hemorrhages in The Fat Tissue and Fat EmbolismDocument4 pagesAn Autopsy Case of Decompression Sickness - Hemorrhages in The Fat Tissue and Fat EmbolismVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Sanofi Pasteur CYD14 Full Results 11 July FINAL enDocument4 pagesSanofi Pasteur CYD14 Full Results 11 July FINAL enVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- A Case of Decompression Illness During Saturation DivingDocument2 pagesA Case of Decompression Illness During Saturation DivingVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Decompression Sickness Treatment: First AidDocument8 pagesDecompression Sickness Treatment: First AidVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- AKI Due To DCSDocument3 pagesAKI Due To DCSVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- The Mechanism of Decompression IllnessDocument4 pagesThe Mechanism of Decompression IllnessVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Vaccine DengueDocument9 pagesVaccine DengueVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Asthma During Pregnancy - Mechanisms and Treatment ImplicationsDocument20 pagesAsthma During Pregnancy - Mechanisms and Treatment ImplicationsVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Adenomyosis and ReproductionDocument3 pagesAdenomyosis and ReproductionVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- EDH Is Surgery Alway Mandatory ?Document6 pagesEDH Is Surgery Alway Mandatory ?Venansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Pathopysiology of AdenomyosisDocument11 pagesPathopysiology of AdenomyosisVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- What Decides the Outcome of Viral Infection: Host or VirusDocument23 pagesWhat Decides the Outcome of Viral Infection: Host or VirusVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Differentiating Dengue Virus Infection From Scrub Typhus in Thai Adults With FeverDocument3 pagesDifferentiating Dengue Virus Infection From Scrub Typhus in Thai Adults With FeverVenansius Ratno KurniawanNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Report SampleDocument11 pagesReport SampleArvis ZohoorNo ratings yet

- ......... NCP CaseDocument34 pages......... NCP Casevipnikally80295% (19)

- Wellness massage exam questionsDocument3 pagesWellness massage exam questionsElizabeth QuiderNo ratings yet

- Case Report: Communication Strategies For Empowering and Protecting ChildrenDocument9 pagesCase Report: Communication Strategies For Empowering and Protecting ChildrennabilahNo ratings yet

- Cyclone Shelter Construction Maintenance and Management Policy 2011Document21 pagesCyclone Shelter Construction Maintenance and Management Policy 2011MAHABUBUR RAHAMANNo ratings yet

- BS EN 752-2 Drains & Sewer PDFDocument21 pagesBS EN 752-2 Drains & Sewer PDFsefaz50% (2)

- SGLGB Form 1 Barangay ProfileDocument3 pagesSGLGB Form 1 Barangay ProfileMark Lenon Par Mapaye100% (1)

- SImOS Nano-Tera 2013Document35 pagesSImOS Nano-Tera 2013nanoteraCHNo ratings yet

- Radiographic Cardiopulmonary Changes in Dogs With Heartworm DiseaseDocument8 pagesRadiographic Cardiopulmonary Changes in Dogs With Heartworm DiseaseputriwilujengNo ratings yet

- Gurr2011-Probleme Psihologice Dupa Atac CerebralDocument9 pagesGurr2011-Probleme Psihologice Dupa Atac CerebralPaulNo ratings yet

- MBSR Standards of Practice 2014Document24 pagesMBSR Standards of Practice 2014wasdunichtsagst100% (1)

- A6013 v1 SD Influenza Ag BrochureDocument2 pagesA6013 v1 SD Influenza Ag BrochureYunescka MorenoNo ratings yet

- FreezingDocument59 pagesFreezingManoj Rathod100% (1)

- Handbook of Laboratory Animal Science - Vol IIIDocument319 pagesHandbook of Laboratory Animal Science - Vol IIICarlos AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Experential and Relationship Oriented Approaches 1Document12 pagesExperential and Relationship Oriented Approaches 1Mary Ann CabalejoNo ratings yet

- Management of Class I Type 3 Malocclusion Using Simple Removable AppliancesDocument5 pagesManagement of Class I Type 3 Malocclusion Using Simple Removable AppliancesMuthia DewiNo ratings yet

- GIGITAN ULAR BERBISA: GEJALA, PENANGANAN DAN JENIS ULAR PALING BERBISADocument19 pagesGIGITAN ULAR BERBISA: GEJALA, PENANGANAN DAN JENIS ULAR PALING BERBISAYudhistira ArifNo ratings yet

- Admission For 1st Year MBBS Students For The Academic Year 2014-2015Document10 pagesAdmission For 1st Year MBBS Students For The Academic Year 2014-2015Guma KipaNo ratings yet

- Labcorp: Patient ReportDocument4 pagesLabcorp: Patient ReportAsad PrinceNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Pengetahuan Sikap Penderita Penyakit Malaria FalciparumDocument63 pagesHubungan Pengetahuan Sikap Penderita Penyakit Malaria FalciparumEsty GulsanNo ratings yet

- College Women's Experiences With Physically Forced, Alcohol - or Other Drug-Enabled, and Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault Before and Since Entering CollegeDocument12 pagesCollege Women's Experiences With Physically Forced, Alcohol - or Other Drug-Enabled, and Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault Before and Since Entering CollegeGlennKesslerWP100% (1)

- 11 - Chapter 7 PDFDocument41 pages11 - Chapter 7 PDFRakesh RakiNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument11 pagesDrug StudyHennah Reblando100% (3)

- As 2550.5-2002 Cranes Hoists and Winches - Safe Use Mobile CranesDocument8 pagesAs 2550.5-2002 Cranes Hoists and Winches - Safe Use Mobile CranesSAI Global - APACNo ratings yet

- Week 6 - LP Modeling ExamplesDocument36 pagesWeek 6 - LP Modeling ExamplesCharles Daniel CatulongNo ratings yet

- Influence of Social Capital On HealthDocument11 pagesInfluence of Social Capital On HealthHobi's Important BusinesseuNo ratings yet

- Wto Unit-2Document19 pagesWto Unit-2Anwar KhanNo ratings yet

- Municipal Ordinance No. 05-2008Document5 pagesMunicipal Ordinance No. 05-2008SBGuinobatan100% (2)

- Design and Estimation of Rain Water Harvesting Scheme in VIVA Institute of TechnologyDocument4 pagesDesign and Estimation of Rain Water Harvesting Scheme in VIVA Institute of TechnologyVIVA-TECH IJRINo ratings yet

- Roberts Race Gender DystopiaDocument23 pagesRoberts Race Gender DystopiaBlythe TomNo ratings yet