Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The 20marcgraf 20map 20of 20brazil

Uploaded by

MateusNavaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The 20marcgraf 20map 20of 20brazil

Uploaded by

MateusNavaCopyright:

Available Formats

qua parte facet

BIAGI

*

.

r. Jr

yaye .' , , , theri

fact, the vignettes so dominate the map that the coastline with its

rivers and place-names seems of secondary importance.

The illustrations on early maps, and especially those purport-

ing to show native peoples and their milieu, are often several

steps from reality, being idealised from crude sketches or merely

adapted from previous engravings. Those on the Marcgraf map

are altogether of a different class. They were drawn by the Dutch

artist Frans Post (1612-80) of Haarlem, one of the most talented

artists employed in Brazil by Johan Maurits and a man with an

almost fanatical preoccupation with detail, as can be seen in the

many subsequent paintings that he built up from sketches

brought back to Europe in 1644. Furthermore, the vignettes do

not show famous episodes, heroic battles, native 'types' looking

like Europeans in feathers and beads, or mythical animals: they

illustrate everyday colonial life. Outside the sugar mill, negroes

play music and dance, while the mill owner in a broad-brimmed

hat leans over his balcony, apparently conversing with another

on horseback. Every operational detail of the sugar and manioc

mills is carefully spelled out, so that such mills could probably be

reconstructed from these drawings. Of exceptional interest are

the scenes of the Tapuya Indians, dancing, drinking, hunting

`ostriches' (presumably rheas), and in one vignette clubbing,

dismembering and roasting their enemies. Did Frans Post

witness such cannibalism? Only twice are Tapuyas shown in his

paintings, so that these vignettes may well be a most precious

supplement to Post's documentation of Brazil. Taken as a whole,

the vignettes probably offer a more realistic view of life in an

exotic land than those of any other map of the period.

Yet another aspect of great interest in this Brazil map is its

printing history. It first appeared as four plates in the Rerum per

octennium in Brasilia . . . historia, the panegyric published in

1647 (the same year as the Blaeu map) by Caspar van Baerle or

Barlaeus on the eight years that Johan Maurits was Governor-

General of Dutch Brazil. These maps showed successively the

coasts of the captaincies of Sergipe, southern Pernambuco,

northern Pernambuco with Itamaraca, and Paraiba with Rio

Grande. The last two maps included the vignettes of the sugar

mill and the Tupinamba village, but the upper four vignettes (a,

b, c, d. See illustration) were not used (except for a part of the

seine-netting scene on the second map). The remaining illustra-

tions in Barlaeus were engraved from ink and wash drawings by

Frans Post, which are now in a bound volume in the Department

of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum (No 197* a2; 31

drawings and one unused). Unfortunately, the original drawings

for the four map vignettes are not known. Possibly they

remained with Blaeu, together with the original draft for the

map, and could thus have been lost in the fire at the Blaeu works

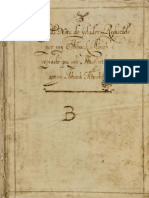

in 1672. What may be part of an early draft of the map, or

perhaps a copy, is in the Algemeen Rijksarchief in The Hague. It

does not conform to the Barlaeus divisions, overlapping parts of

both the first and second maps, but bears the same explanation

and attribution to Marcgraf (here Latinized as Marggrafius, not

Marggraphius).

The four Barlaeus maps were of different shapes and did not

include the four vignettes and title (upper right part of the map),

nor the explanatory text and decoration (lower left part of the

map). In making a rectangular wall map of these, Blaeu fitted

them together, leaving edges where they could be glued and

adding four irregular sheets for the vignettes top right and an L-

shaped sheet bottom left, thus making nine awkward sheets plus

two narrow strips to fill in gaps. Below this, in Latin, Dutch and

French, he added a long text on Brazil based on Barlaeus. The

map itself was 163.7 cm wide and 102.0 cm deep (or 148.8 cm

deep including the text). In the Klenck version the boundaries

are hand-coloured in green, pink and yellow.

Unexpectedly, the Klenck Atlas is not unique. In the

Deutsche Staatsbibliothek in East Berlin is an almost identical

atlas presented to Friedrich Wilhelm, the Great Elector, by none

other than Johan Maurits in 1664 (they were cousins and the

Elector had earlier taken Johan Maurits into his service). Athird

Below:

The main title of Allard's edition of 1659, unlike Blaeu's, includes captions (left to right beginning at the top): Tamandua guaer ofte mieren eeterZyn Tonge is langh 7

Vierendel van een ellen dick gelyck a/s een bas snaer(Tamandua guaer [misreading for guacu] or anteater his tongue is long as four and a part ells [ell=69 cm] thick as a

bass string); Ai ofte Luyaert gaende s dags omterent 20 Passen weeghs a/s hy zy best doet (ai or sloth going per day about twenty paces when he does his best);

Brasiliense muffs (Brazilian mouse); Brasiliaenen Vtfelucht over de Victori van haer batalien (Brazilian joy over victory of their battle); de Bradery (the roasting); de Strut's

Jacht (the ostrich hunt). (By courtesy of Leiden University Library).

Count Johan Maurits of Nassau-Siegen was Governor-General of the

Dutch West India Company holdings in Brazil from 1637 to 1644. He

employed Georg Marcgraf as one of a team recording the new land.

This poi trait of Maurits in oils is by Jan de Baen.

The Marcgraf

Map of Brazil

by Peter J. Whitehead

4

Joan Blaeu produced his own (wall-map) edition of the Marcgraf map later in 1647. The

illustration has been marked to show how the nine irregular sheets forming the map were pasted

together. Allard in 1659 and de Jonghe in 1664 rationalised the sheets into nine more or less

equal rectangles. (By courtesy of the British Library)

Dr Whitehead is aPrincipal Scientific Officer in the Zoology

Department of the British Museum (Natural History), specialising

in the taxonomy of herring-like fishes. For many years he has had

adeep interest in the Dutch period in Brazil and has published a

number of articles on the subject. His book on Dutch Brazil, with

fellow ichthyologist Martin Boeseman of Leiden, published

recently, explores the pictorial record of this episode in Dutch

colonial history. Here he examines the famous wall-map of Brazil

in the Klenck atlas.

ONE OF THE great treasures of the map collection in the

British Library is the enormous Klenck Atlas, 1.7 metres high

and opening to a spread of almost 2 metres (5'/zft x 6'/2ft), so

large in fact that it stands in a special glass case and must be

wheeled out into the Students Room of the Map Library. It was

presented to Charles II on his accession in 1660 by a group of

Amsterdam merchants headed by Johannes Klenck (misspelt

Klencke), Professor of Philosophy at the University. The Klenck

Atlas is also noteworthy because it includes one of only four

known copies of the famous wall map of Brazil published by Joan

Blaeu in 1647. Although parts of this map had appeared in book

form in the same year, and the complete map was later twice

copied, it is the original Blaeu version that is the most

celebrated. Not only is it one of the most elegant Dutch maps of

that period, but it remained for over a century the best guide to

north-eastern Brazil.

This map can be dubbed the `Marcgraf map' after its author,

Georg Marcgraf (1610-43), a young German polymath from

Liebstadt near Dresden, who was serving as cartographer,

astronomer, zoologist and botanist to Count Johan Maurits of

Nassau-Siegen, Governor-General from 1637 to 1644 of the

Dutch West India Company holdings in Brazil. Marcgraf's

authorship seems to have gone unrecorded in the West India

Company documents, apart from occasional statements that he

was occupied in cartographic work, but it is attested in a caption

to the map which reads: Quam proprijs observationibus ac

dimensionibus, diturnau peregrinationi ase habitis, fundamentali-

tur superstruabat & delineabat Georgius Marggraphius Germa-

nus, Anno Christi 1643. Marcgraf was one of a team of scientists,

artists, craftsmen and others brought out to Brazil by Johan

Maurits to explore and record every detail of this new land. He

had been a wandering scholar, visiting ten different universities

in about as many years and studying medicine, mathematics,

astronomy and botany, but never apparently with a formal

training in cartography. It is curious, therefore, that Marcgraf

was chosen for such a large project when the well-known

cartographer Cornelis Golijath, one of the best of Dutch

mapmakers, was employed in 1638-41 to make a general map of

the Dutch territories in Brazil. The Golijath map was never in

fact published and is known only through two manuscript copies

made by Johannes Vingboons (son of Philips Vingboons, author

of the 1637 Brasilysche Paskaert). One copy is in the H. G. Born

Atlas in the Instituto Archeologico Pernambucano in Recife,

while the other is in volume 2 of the Vingboons Atlas in the

Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana in Rome. In general, the

Marcgraf map is superior in cartographic indications, whereas

the Golijath/Vingboons map is richer in place names and other

details. This seems to imply that the two did not pool their

information. Certainly, Golijath left Brazil in 1641 to attend the

coronation of Joao IV of Portugal (which would have given

Marcgraf the opportunity to replace him), but his 1648 map of

the Recife area has sufficient up-to-date information that one

can suspect that Golijath returned. Nevertheless, the Blaeu map

bears Marcgraf's name and makes no mention of Golijath. It

would be interesting to discover the true relationship between

the two men's work, but in any event it is clear that Marcgraf was

no simple plagiarizer.

The Marcgraf map has much more of interest, however,

besides its cartographic information. This was the great period of

Dutch wall-maps, elegant pieces to be hung in bourgeois homes,

as seen in the interiors by Vermeer and others. Such maps

required vignettes, decorative borders, informative texts, in fact

all those elements of story-telling that could transform specialist

cartography into popular geography. The Marcgraf map is no

exception. Every spare part is crowded with aspects of Brazilian

life. They show small scenes characteristic of the four groups of

inhabitants the Europeans as colonists and landowners, the

negroes as slaves in the sugar industry, the `savage' Tapuyas

(correctly Tarairius) with a reputation for eating their enemies,

and the more `civilised' Tupinambas settled in aldeias or villages

under Dutch supervision. Combined with this ethnographic

programme are scenes of economic activity (a sugar mill, a

manioc plantation and mill, fishing with a seine net), typical

Brazilian animals (anteater, sloth, boa constrictor, etc.), and in a

festoon under the main title BRASILIA quaparte paret BELGIS

some examples of Indian weapons and musical instruments. In

iF

The vignettes include a

seine-netting scene with

manioc and sugar

plantations below. Allard

gives the following captions

(left to right, top to bottom):

Schilt wacht omt'

Waerschouwen wanner

d'Visschers met Vis aen

coomen (Watch to warn

when the fishermen come

with the fish); Faringe

Planttagie wiens Wortelin

plaetse Van broot werdt

genutticht ( Manioc

plantation whose root was

eaten in place of bread);

Faringe werdt alhiergerast

[geraspt] en gedroocht (Flour

was here ground and dried);

Thugs van d'Heer van een

SukckerMoolen (House of

the master of a sugar mill).

(By courtesy of Leiden

University Library).

The third edition of the Marcgraf map was that published by

Clement de Jonghe of Amsterdam in 1664. At least three copies

exist: in the British Library, in the Maritiem Museum 'Prins

Hendrik' in Rotterdam, and in the Ministerio das Relacoes

Exteriores (Ministry of Foreign Relations) in Rio de Janeiro. De

Jonghe followed Allard in using nine more or less equal sheets,

thus again elongating the left vignette, but there are some

puzzling differences. Although he copied Allard (or Barlaeus) in

omitting the procession and also the palms at the top of Paraiba

with Rio Grande, he took only some of the Allard captions (with

some spelling changes), leaving out most of those describing the

scenes. Once again, the copying of topographical detail and

place-names is very exact, although the engraver was sometimes

rather careless, as when he dated the fourth sea battle as An

MDXL and entirely forgot to inscribe Rio Grande on the banner

below the arms for that captaincy.

In the history of cartography there are a number of truly great

maps, great because of their subject or their unique survival or

their association with some famous figure in a particular phase of

the art. The Marcgraf map of Brazil is perhaps in a more modest

category. Yet its elegance, its balance between cartographic and

socio-ethnographic information, its power to evoke lost scenes of

colonial life, its considerable accuracy and the recognition that

was accorded to it at the time (by inclusion in the Klenck and

other prestigious atlases) give it a rather special place in the

evolution of maps.

It was Allard and de Jonghe, furthermore, who recognised a

need for further editions of the complete wall-map with its

vignettes and it is much to their credit that they took such pains

to reproduce every cartographic and pictorial detail with

exactness. In this way, at least nine examples have come down to

us as a record of the skills of Georg Marcgraf, Frans Post, some

unrecorded engravers and above all the marvellous energy and

enthusiasm of a colonial governor, Johan Maurits, who con-

ceived and largely financed the project.

Amore detailed analysis of the map, together with full

bibliographic references, is given by:

P. J. P. Whitehead &M. Boeseman, 1987. A portrait of

Dutch seventeenth century Brazil. animals, plants and people

by the artists of Johan Maurits of Nassau. Amsterdam:

Koninklijkc Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen and

North-Holland Publishing Company.

References:

1. Wall-maps in Dutch paintings are sometimes of such accuracy that they can help

to elucidate the history of the map itself (see for example James A. Welu, 1978.

'The map in Vermeer's art of painting', Imago Mundi, 30. pp 9-30. The

Marcgraf map is not known from any painting, but the 1630 'news map' of

Recife by Claes Jansz. Visscher appears in a Dutch interior by Jacob Duck.

2. The Berlin atlas has been rebound with wooden boards and rather ugly baroque

metal decoration, but the Rostock atlas has an original binding almost identical

to that of the Klenck, being a series of diamond shapes (occupied by roses,

fleurs-de-lys, thistles or harps in the Klenck version). Their parentage is the

same, the Klenck being inscribed on the spine Kees Dierkz. et filius D. K.

compegerunt anno 1660 and the Rostock Kors Dierksen et filius D. Korsen

compegerunt anno 1664. Since the Klenck and Berlin atlases were gifts to very

prominent men, one would expect the same of the Rostock atlas, but its

provenance is unknown.

3. In some, perhaps many. copies of Barlaeus one or more second state maps have

been substituted for the originals. Thus the British Library copy (formerly

owned by Sir Joseph Banks) has no negro on the watch tower (map 2), nor

procession with horseman and palanquin (map 3), whereas in the coloured copy

of Barlaeus in the Royal Geographical Society Map Room these elements are

present (second state). In the copy of Barlaeus used by S. P. 1'H. Naber for his

Dutch translation (1923) map 4 was in the second state (additional palms, texts

for sea battles IiIV).

4. Acoloured copy of the Dutch edition (1665) was examined in the Royal

Geographical Society Map Room, entitled Derde deel van 't achste stuck der

aerdrycks-beschrvving, welck vervat America. The text and maps occupy

signatures S2S7, the four maps being out of their Barlaeus order map (1 S3;

map 3 S4; map 2 S5; map 4 S6), as correctly indicated by Koeman (Atlantes

neerlandici, 1:244). 1 am indebted to Francis Herbert of the Royal Geographical

Society for drawing my attention to this and to their coloured Barlaeus and for

much helpful criticism of my text.

20

S :. . erwcr

. a m . / . . . 1. 4,0f

77,C. <. 7"rre. 4. -irkvier073. 4. . ,,,,Ocect:

it' &wefts, d.sii4y1/47b....,

o. 7:16

1

. . . e4texti. er,". .

v

. 27

1,44 ,

Res il

j,-114cter

Ca"

.

.ArZSZrge t rtile el

1.7'n et 11,ays..

r ,

gs. F. Priluleilens.

mit ialay

zem et ftirier .

69, 7, ; (.4

ecps.

Above:

The Marcgraf Blaeu map of Brazil was first published as four plates in 1647 in Barlaeus's Rerum per octennium in Brasilia . . . historia. The detail shown here is from the

map of northern Pernambuco and Itamaraca. (By courtesy of the Royal Geographical Society, London)

such huge atlas is in the University Library at Rostock in East

Germany.2

Both the Berlin and the Rostock atlases include the Marcgraf

map (sheets 35 and 32 respectively). Yet another copy of this

Blaeu map, and apparently the only known example that still

exists as a traditional wall-map, was in the possession of the

Utrecht dealer R. C. Bracken in 1983. It differs from the other

three in that the Latin text is mounted vertically down the right

side, the Dutch replaces the Latin at the bottom, while the

French runs down the left side; also, it is uncoloured.

The Barlacus maps can be considered as a first state.

Presumably Blaeu, who was the publisher of the Barlaeus book,

had seen the possibility of making a complete map and

commissioned the vignettes from Frans Post. Why he should

have allowed the second Barlaeus map to be of a different width

(southern Pernambuco almost 10 cm narrower than the rest) is

mysterious, although the heights are much the same. The

overlap areas were already marked by lines on the Barlaeus

sheets, showing that a pasted-up complete version was planned.

Curiously, however, Blaeu then decided to make several small

alterations. For example, he placed a negro on the watch tower

overlooking the seine netting scene, added a procession with a

palanquin, woman with basket and man on horseback below the

sugar mill, placed two extra palms at the top of Paraiba with Rio

Grande, and supplied captions to the sea battles numbered H-

IV. With the addition of the vignettes, this can be considered as

the second state of the map.3

The Blaeu edition can be instantly recognised by the large

palm on the right of the sugar mill buildings and a smaller one

above the Tupinamba village buildings (both on the Paraiba with

Rio Grande map). Both the later Allard and the de Jonghe

editions have a honey bee and a grasshopper below the swags of

flowers in the top right vignette, as well as at least some captions

to the animals and scenes. The Allard alone has a small palm

added to the left of the manioc scene, just below the fishermen,

while the de Jonghe edition is immediately recognisable by

provision of the motto Honi soit qui mal y pense around the arms

of Prince Frederik Hendrik, the Stadholder, who had been

nominated knight of the Order of the Garter in 1627 (his are the

righthand arms hung from the festoon below the main title).

Blaeu re-issued the four maps in editions of his Atlas Major

(Latin, 1662; Dutch, 1665), using the second state, but otherwise

in the form used in the Barlaeus book.4

The subsequent printing history of the Marcgraf map poses

tantalising questions regarding copyright, pirating and the

economics of producing other editions of maps. Twelve years

after the Blaeu edition of 1647, Huych Allard (or Huijch Allart)

of Amsterdam published a new edition of the map. Careful

comparison of the details shows that although the topographical

lines and the place names are almost identical, they were in fact

re-engraved. Allard sensibly rationalised the awkward Blaeu

arrangement by making nine more or less equal sheets of

approximately 38.5 by 52.7 cm. He extended the bottom to give

more room for the sea battles, which meant elongating the

vignette on the left side, and he provided Dutch captions for the

animals and the scenes. It seems possible that he re-engraved the

two right maps (northern Pernambuco and Paraiba with Rio

Grande) from original Barlaeus examples, since the procession

in the first and the two palms in the second are missing. An

incomplete copy of the Allard map (top right sheet missing) is in

the Bodel Nijenhuis collection, p. 219, No. 60, in the Universi-

teitsbibliotheek in Leiden, while a complete copy was offered for

sale by Sotheby's recently (October 23, 1986, item 141,

illustrated on p. 77 of catalogue); it was suggested in the

catalogue that the imprint date of 1659 had been altered from

1657.

19

You might also like

- The original drawings for the Historia naturalis Brasiliae of Piso and Marcgrave (1648Document14 pagesThe original drawings for the Historia naturalis Brasiliae of Piso and Marcgrave (1648Sergio Ríos DíazNo ratings yet

- Jacob Van Deventer - OdtDocument2 pagesJacob Van Deventer - OdtPilar Rubio SabugueiroNo ratings yet

- Braun and Hogenberg's Civitates Orbis Terrarum AtlasDocument2 pagesBraun and Hogenberg's Civitates Orbis Terrarum AtlasMichaelNo ratings yet

- The Miller AtlasDocument29 pagesThe Miller AtlasTuls FdezNo ratings yet

- World in Maps Booklet v5 AccessibleDocument15 pagesWorld in Maps Booklet v5 AccessibleLoveGeneration for ever100% (1)

- Map of World 00 SantDocument70 pagesMap of World 00 Santmarcoapina33% (3)

- The Vesconte Maggiolo World Map of 1504 in Fano, Italy: Second EditionDocument100 pagesThe Vesconte Maggiolo World Map of 1504 in Fano, Italy: Second EditionallingusNo ratings yet

- HES & DE GRAAF Catalogue 2012Document16 pagesHES & DE GRAAF Catalogue 2012HES&DEGRAAFNo ratings yet

- History of Cartography, Portolan Charts 13th Century To 15th CenturyDocument93 pagesHistory of Cartography, Portolan Charts 13th Century To 15th Centuryaa2900100% (2)

- Three Historic Atlases from the Golden Age of CartographyDocument12 pagesThree Historic Atlases from the Golden Age of Cartographyjanhuszar100% (2)

- Unraveling an Ancient EnigmaDocument20 pagesUnraveling an Ancient Enigmamarco spada100% (1)

- 1b The Middle KingdomDocument13 pages1b The Middle KingdomAsmaa MahdyNo ratings yet

- Map TavolaDocument2 pagesMap TavolajorgericharNo ratings yet

- A Forgotten Ptolemy: Harley Codex 3686 in The British LibraryDocument23 pagesA Forgotten Ptolemy: Harley Codex 3686 in The British Librarymontag2No ratings yet

- Cartas Pre 1500Document93 pagesCartas Pre 1500Valdir de SouzaNo ratings yet

- The Spanish Gospel of Barnabas ManuscriptDocument7 pagesThe Spanish Gospel of Barnabas Manuscriptعبد الخالق الهاشمي العلويNo ratings yet

- 47 Maps and Descriptions of The WorldDocument17 pages47 Maps and Descriptions of The Worldyahya333No ratings yet

- History of Cartography Volume1 GalleryDocument32 pagesHistory of Cartography Volume1 GalleryAndré Mendes100% (1)

- Medieval Woodcut Illustrations: City Views and Decorations from the Nuremberg ChronicleFrom EverandMedieval Woodcut Illustrations: City Views and Decorations from the Nuremberg ChronicleRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied's Travels in BrazilDocument5 pagesMaximilian of Wied-Neuwied's Travels in Brazilmissinvisible71No ratings yet

- P15324coll10 198745Document66 pagesP15324coll10 198745Adriana CarpiNo ratings yet

- The Chronicle of the Discovery and Conquest of Guinea Vol. IFrom EverandThe Chronicle of the Discovery and Conquest of Guinea Vol. INo ratings yet

- Harti Vechi PDFDocument15 pagesHarti Vechi PDFdanyboy80No ratings yet

- The Arms of The RomansDocument97 pagesThe Arms of The RomansTheWracked100% (1)

- Aula Mapas CronológicosDocument27 pagesAula Mapas CronológicosBruno TeixeiraNo ratings yet

- Charlotte Du Rietz Rare Books - Catalogue 36Document32 pagesCharlotte Du Rietz Rare Books - Catalogue 36BaigalBaldandorjNo ratings yet

- Peter Wick Cat152nDocument39 pagesPeter Wick Cat152naldoremo19650% (1)

- Books: Rembrandt. The New Hollstein Dutch & Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts 1450-1700. by ErikDocument2 pagesBooks: Rembrandt. The New Hollstein Dutch & Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts 1450-1700. by Erik77bgfaNo ratings yet

- QuaritchDocument32 pagesQuaritchAlexNo ratings yet

- BARTHELMESS, Klaus. 2009. Basque Whaling in Pictures, 16th-18th CenturyDocument26 pagesBARTHELMESS, Klaus. 2009. Basque Whaling in Pictures, 16th-18th CenturyDiegoNo ratings yet

- Whitehead - A Portrait of Dutch 17th Century Brazil - 1989 - OCRDocument185 pagesWhitehead - A Portrait of Dutch 17th Century Brazil - 1989 - OCRRoger CodatirumNo ratings yet

- MP Cat 56 - USDocument40 pagesMP Cat 56 - USNikos VaxevanidisNo ratings yet

- Expert Analysis of Art Review from 1937Document3 pagesExpert Analysis of Art Review from 1937Samuel Vilella MartínezNo ratings yet

- The Story of Geographical Discovery: How the World Became KnownFrom EverandThe Story of Geographical Discovery: How the World Became KnownNo ratings yet

- Frans Post's Brazil - Fractures in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Colonial Landscape PaintingsDocument22 pagesFrans Post's Brazil - Fractures in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Colonial Landscape PaintingsBlue LangurNo ratings yet

- Eng7921 7586Document4 pagesEng7921 7586NUR ZAEYRY AHMAD HASHIMNo ratings yet

- Lowlands Sixteenth Century Cartography Mercators BirthDocument17 pagesLowlands Sixteenth Century Cartography Mercators BirthFelipe ReyesNo ratings yet

- Leopold Von Ranke: History of The Popes Vol 1 (1902)Document396 pagesLeopold Von Ranke: History of The Popes Vol 1 (1902)krca100% (1)

- BuacheDocument8 pagesBuachewalid ben aliNo ratings yet

- Making of Modern Europe 1648 1780Document87 pagesMaking of Modern Europe 1648 1780René Lommez GomesNo ratings yet

- Christian Art Influence in ChinaDocument24 pagesChristian Art Influence in ChinakarlkatzeNo ratings yet

- Napoleon and the Archduke Charles: A History of the Franco-Austrian Campaign in the Valley of the Danube 1809From EverandNapoleon and the Archduke Charles: A History of the Franco-Austrian Campaign in the Valley of the Danube 1809Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Early Modern History Tutorial 2 PrepDocument6 pagesEarly Modern History Tutorial 2 PrepBronte HargreavesNo ratings yet

- Collectanea Napoleonica - Napoleon I and His Times (1769-1821) - Daniell 1900Document194 pagesCollectanea Napoleonica - Napoleon I and His Times (1769-1821) - Daniell 1900Kassandra M Journalist100% (1)

- 1.weigel Topographical Turn 2009Document15 pages1.weigel Topographical Turn 2009janfalNo ratings yet

- Collaboration in A Fourteenth-Century Psalter The Franciscan Iconographer and The Two Flemish Illuminators of MS 3384, 8o in The Copenhagen Royal Library by Kerstin B. E. CARLVANTDocument36 pagesCollaboration in A Fourteenth-Century Psalter The Franciscan Iconographer and The Two Flemish Illuminators of MS 3384, 8o in The Copenhagen Royal Library by Kerstin B. E. CARLVANTneddyteddyNo ratings yet

- Bibliographical Summary of The Seventeen Editions of The First LetterDocument9 pagesBibliographical Summary of The Seventeen Editions of The First LetterRadioactivetoyNo ratings yet

- The Surprising Adventures of Baron MunchausenFrom EverandThe Surprising Adventures of Baron MunchausenRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (137)

- Psy7541 6154Document4 pagesPsy7541 6154Nur Amaliyah PutriNo ratings yet

- Mapping The Traveled SpaceDocument15 pagesMapping The Traveled SpaceAnonymous yAH8LaVDUCNo ratings yet

- SAmagra 2010 Vol&6 Page 01 11Document11 pagesSAmagra 2010 Vol&6 Page 01 11Kp RajeshNo ratings yet

- Genealogical Records of the Aboab FamilyDocument27 pagesGenealogical Records of the Aboab FamilykatiaferesNo ratings yet

- (1885) Katalog Der Ausgestellten GemaldeDocument340 pages(1885) Katalog Der Ausgestellten GemaldeHerbert Hillary Booker 2ndNo ratings yet

- 378 Dauphin PDFDocument41 pages378 Dauphin PDFSaulo CastilhoNo ratings yet

- European Crowns: 1700-1800 / by John S. DavenportDocument334 pagesEuropean Crowns: 1700-1800 / by John S. DavenportDigital Library Numis (DLN)100% (6)

- Albert Eckhout's portraits reveal insights into Dutch colonial BrazilDocument32 pagesAlbert Eckhout's portraits reveal insights into Dutch colonial BrazilJoaquim AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- The Catalan Atlas of 1375 and Competing Eschatological Views Among Jews and ChristiansDocument21 pagesThe Catalan Atlas of 1375 and Competing Eschatological Views Among Jews and ChristiansAna Isabel Sanchez RomeroNo ratings yet

- Cantino PlanisphereDocument4 pagesCantino PlanisphereNidhy KhajuriaNo ratings yet

- Personal PronounsDocument4 pagesPersonal Pronounsstar0157No ratings yet

- Word Bank HalloweenDocument2 pagesWord Bank HalloweenEray KaraNo ratings yet

- 21-26 Raggedy Ann Saved Fido 0Document6 pages21-26 Raggedy Ann Saved Fido 0MateusNavaNo ratings yet

- 16-20 Raggedy Ann and The Painter 0Document5 pages16-20 Raggedy Ann and The Painter 0MateusNavaNo ratings yet

- Raggedy Ann KittensDocument7 pagesRaggedy Ann KittensMateusNavaNo ratings yet

- Traditional Songs General Activities PDFDocument70 pagesTraditional Songs General Activities PDFnittty_wittyNo ratings yet

- 27-31 Raggedy Anns Trip On The River 0Document5 pages27-31 Raggedy Anns Trip On The River 0MateusNavaNo ratings yet

- Raggedy Ann Learns Not to Take Without AskingDocument5 pagesRaggedy Ann Learns Not to Take Without AskingMateusNavaNo ratings yet

- A Beautiful MindDocument31 pagesA Beautiful MindIrfan AshrafNo ratings yet

- InvençõesDocument3 pagesInvençõesMateusNavaNo ratings yet

- Script Sherlock HolmesDocument159 pagesScript Sherlock HolmesMateusNavaNo ratings yet

- Stylistic Analysis of McGough's "40-LoveDocument3 pagesStylistic Analysis of McGough's "40-LoveVanina Oroz De GaetanoNo ratings yet

- Raggedy Ann StoriesDocument83 pagesRaggedy Ann StoriesMateusNavaNo ratings yet

- 2005 GerzymischArbogast HeidrunDocument15 pages2005 GerzymischArbogast HeidrunMateusNavaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 MafinDocument36 pagesChapter 9 MafinReymilyn SanchezNo ratings yet

- Tle-Bpp 8-Q1-M18Document14 pagesTle-Bpp 8-Q1-M18Michelle LlanesNo ratings yet

- 5 - Econ - Advanced Economic Theory (Eng)Document1 page5 - Econ - Advanced Economic Theory (Eng)David JackNo ratings yet

- Blaise PascalDocument8 pagesBlaise PascalBosko GuberinicNo ratings yet

- Parashara'S Light 7.0.1 (C) Geovision Software, Inc., Licensed ToDocument5 pagesParashara'S Light 7.0.1 (C) Geovision Software, Inc., Licensed TobrajwasiNo ratings yet

- PHILIPPINE INCOME TAX REVIEWERDocument99 pagesPHILIPPINE INCOME TAX REVIEWERquedan_socotNo ratings yet

- Assisting A Tracheostomy ProcedureDocument2 pagesAssisting A Tracheostomy ProcedureMIKKI100% (2)

- PIC16 F 1619Document594 pagesPIC16 F 1619Francisco Martinez AlemanNo ratings yet

- Psychology - A Separate PeaceDocument2 pagesPsychology - A Separate PeacevasudhaaaaaNo ratings yet

- Personal Weaknesses ListDocument3 pagesPersonal Weaknesses ListKinga SzászNo ratings yet

- Comic Conversations – Lesson Plan & TemplatesDocument15 pagesComic Conversations – Lesson Plan & TemplatesShengdee OteroNo ratings yet

- Life and Works of Jose RizalDocument5 pagesLife and Works of Jose Rizalnjdc1402No ratings yet

- Merry Almost Christmas - A Year With Frog and Toad (Harmonies)Document6 pagesMerry Almost Christmas - A Year With Frog and Toad (Harmonies)gmit92No ratings yet

- Epithelial and connective tissue types in the human bodyDocument4 pagesEpithelial and connective tissue types in the human bodyrenee belle isturisNo ratings yet

- Comparative Ethnographies: State and Its MarginsDocument31 pagesComparative Ethnographies: State and Its MarginsJuan ManuelNo ratings yet

- Aiatsoymeo2016t06 SolutionDocument29 pagesAiatsoymeo2016t06 Solutionsanthosh7kumar-24No ratings yet

- Simple Past Tense The Elves and The Shoemaker Short-Story-Learnenglishteam - ComDocument1 pageSimple Past Tense The Elves and The Shoemaker Short-Story-Learnenglishteam - ComgokagokaNo ratings yet

- Operations Management 2Document15 pagesOperations Management 2karunakar vNo ratings yet

- The Pantheon of Greek Gods and GoddessesDocument2 pagesThe Pantheon of Greek Gods and Goddessesapi-226457456No ratings yet

- Forms and Types of Business OrganizationDocument2 pagesForms and Types of Business Organizationjune hetreNo ratings yet

- The Meaning of Al FatihaDocument11 pagesThe Meaning of Al Fatihammhoward20No ratings yet

- AwsDocument8 pagesAwskiranNo ratings yet

- Circumstances Which Aggravate Criminal Liability People vs. Barcela GR No. 208760 April 23, 2014 FactsDocument8 pagesCircumstances Which Aggravate Criminal Liability People vs. Barcela GR No. 208760 April 23, 2014 FactsJerome ArañezNo ratings yet

- Understanding Deuteronomy On Its Own TermsDocument5 pagesUnderstanding Deuteronomy On Its Own TermsAlberto RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Engineering Economy Course SyllabusDocument11 pagesEngineering Economy Course Syllabuschatter boxNo ratings yet

- Ashe v. Swenson, 397 U.S. 436 (1970)Document25 pagesAshe v. Swenson, 397 U.S. 436 (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Crossing To The Dark Side:: Examining Creators, Outcomes, and Inhibitors of TechnostressDocument9 pagesCrossing To The Dark Side:: Examining Creators, Outcomes, and Inhibitors of TechnostressVentas FalcónNo ratings yet

- Web Search - One People's Public Trust 1776 UCCDocument28 pagesWeb Search - One People's Public Trust 1776 UCCVincent J. CataldiNo ratings yet

- Intrinsic Resistance and Unusual Phenotypes Tables v3.2 20200225Document12 pagesIntrinsic Resistance and Unusual Phenotypes Tables v3.2 20200225Roy MontoyaNo ratings yet

- Network Monitoring With Zabbix - HowtoForge - Linux Howtos and TutorialsDocument12 pagesNetwork Monitoring With Zabbix - HowtoForge - Linux Howtos and TutorialsShawn BoltonNo ratings yet