Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Case of Swine Flu Superinfected With Carbapenem Resistant Klebsiella

Uploaded by

rajdiphazraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Case of Swine Flu Superinfected With Carbapenem Resistant Klebsiella

Uploaded by

rajdiphazraCopyright:

Available Formats

120 Asian Journal of Medical Sciences | Jul-Sep 2014 | Vol 5 | Issue 3

INTRODUCTION

Swine fu is primarily a respiratory disease caused by a

reassortant virus. Though it is usually species specifc (pigs),

occasionally it crosses species barrier and infects humans.

1

First isolation of swine infuenza virus from a human

was done in 1974

2

. In the past, though cases of person to

person transmission have been reported, it resulted in small

outbreaks only.

2

Then in March and April 2009, there was

an outbreak of swine H1N1 infuenza A virus in Mexico

with subsequent cases being detected later in several other

countries including United States and India

3

(so called 2009

fu pandemic). The signs and symptoms of swine fu caused

by H1N1 infuenza A virus are similar to those in seasonal

infuenza virus.

4

However, secondary bacterial pneumonia

may complicate viral pneumonia, especially in pediatric age

group.

4

But among adults, bacterial coinfection is a rarity.

4

Here, we report a case of swine fu superinfected with

carbapenem resistant klebsiella.

CASE REPORT

A 65 years old female patient presented to us with

history of abrupt onset high grade fever along with

chill, headache, dry cough, sore throat, myalgia, malaise

and anorexia of one week duration. The patient was

disoriented, dehydrated and tachypneic. The cough was

nonproductive and nonpurulent. There was no history of

diarrhea or vomiting. Neck rigidity was absent. There was

diminished movement of right side of chest. Also, there

was impaired resonance on percussion. On auscultation

of right side of chest, bronchophony and tubular breath

sounds were found especially in the mid portion. On

routine investigations, neutrophilic leukocytosis (total

white blood cell [WBC] count 13,400 /cu mm with 84%

neutrophil) and moderate anemia (hemoglobin 8.95 g/dL)

were found. Liver function test (LFT) showed elevated

SGPT (serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase- 3706.0

U/L) level. Chest x-ray PA (posteroanterior) view showed

homogenous opacity involving right middle lobe of lung

with no mediastinal shift. Initially she was diagnosed as

a case of viral hepatitis with encephalopathy and chest

infection and treated symptomatically with empirical

antibiotics (co-amoxiclav 1.2 g and metronidazole 500 mg,

both thrice daily intravenously) and adequate hydration.

However on the very next day, the real-time reverse

transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) swine

fu panel was done on throat swab specimen and it showed

a positive result for swine fu (as per report from National

Institute of Cholera and Enteric Diseases [NICED],

Kolkata). Subsequently, neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir

75 mg twice daily through Ryles tube (patient was

disoriented) was started without any delay. For initial couple

A case of swine fu superinfected with carbapenem

resistant Klebsiella

Rajdip Hazra

1

, Manjunatha S.M.

1

, Md Babrak Manuar

1

, Sisir Chakraborty

2

, Kaushik Ghosh

3

1

Department of Anesthesiology, Nilratan Sircar Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, India,

2

Department of Medicine, College of Medicine

and Sagore Dutta Hospital, Kolkata, India,

3

Department of Medicine, Malda Medical College and Hospital, Malda, India

A B S T R A C T

CASE REPORT ASIAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Access this article online

Website:

http://nepjol.info/index.php/AJMS

Submitted: 10-09-2013 Revised: 21-01-2014 Published: 10-03-2014

Address for Correspondence:

Dr. Rajdip Hazra, Department of Anesthesiology, Nilratan Sircar Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal, India.

E-mail: rajdiphazra_nrs@yahoo.co.in; Phone: +918013436607. Copyright AJMS

Swine fu is caused by antigenic shift of infuenza A virus with clinical features similar

to seasonal infuenza virus. Majority of the morbidity and mortality due to swine fu are

attributable to pneumonia and the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Bacterial

superinfection can occur, though it is rare in adults. Here we report a case of swine fu

superinfected with carbapenem resistant Klebsiella, which is often coined as Klebsiella

superbug.

Key words: Swine fu, Bacterial superinfection, Carbapenem resistant Klebsiella

Hazra, et al.: Swine fu with carbapenem resistant Klebsiella

Asian Journal of Medical Sciences | Jul-Sep 2014 | Vol 5 | Issue 3 121

of days, the patient responded with reduced total leukocyte

count (12,200 /cu mm) and SGPT level (402.8 U/L). On

5

th

day of admission, the patient became unconscious,

dyspneic with peripheral desaturation (oxygen saturation

of peripheral arterial blood [SpO

2

] <85%) and crepitations

throughout both lung felds. Arterial blood gas analysis

showed mild respiratory alkalosis (pH) with PaO

2

(partial

pressure of oxygen in blood) of 55 mm Hg. The patient

was immediately intubated and put on mechanical ventilator

on volume control mode (with tidal volume 6 ml/kg of

predicted body weight and positive end expiratory pressure

[PEEP] of 10 cm H

2

O maintaining plateau airway pressure

below 30 cm H

2

O). Antibiotic regimes were changed to

linezolid (600 mg twice daily intravenously) and ceftazidime

(2 g thrice daily intravenously). Chest x-ray PA view revealed

diffuse, bilateral, interstitial and alveolar infltrates. Steroids

(hydrocortisone 100 mg twice daily on intravenous route

and budesonide respules 0.5 mg/2 ml, 4 times a day

through nebulisation) and bronchodilator (salbutamol

respules 5 mg/2.5 ml, 4 times a day through nebulisation)

were added. With these measures, vital hemodynamic

parameters (pulse, respiratory rate, non-invasive blood

pressure and oxygen saturation) became stable. Acute

respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was suspected.

Graveness of the situation was explained to patient party.

Suction material from endotracheal tube was sent for

bacteriological culture and sensitivity maintaining adequate

sterility. Next day, the culture and sensitivity reports were

received. The VITEK 2 Advanced Expert System

TM

(AES) phenotypically identifed the organism as Klebsiella

spp. with ESBL (extended spectrum beta lactamase) +

Carbapenemase (Metallo- or KPC i.e., Klebsiella pneumonia

Carbapenemase) resistance mechanism sensitive only to

colistin (minimal inhibitory concentration [MIC] <0.5

mcg/ml) and intermediate sensitivity to tigecycline (MIC

4 mcg/ml). Then, the patient was started on tigecycline

(100 mg bolus followed by 50 mg every 12 hours through

intravenous route). The rRT-PCR was repeated on throat

swab specimen and it was negative for swine fu virus (as per

report from NICED). Inspite of the treatment, the patient

gradually developed hypoxia followed by type I respiratory

failure. Over next two days, she developed shock and

azotemia. Vasopressor was added (noradrenaline infusion

started initially at 12 mcg/min and later titrated as per blood

pressure). The patient experienced a rapid and progressive

downhill course over the next four days by developing multi

organ dysfunction syndrome. Subsequently, the patient died

on the thirteenth day of admission.

DISCUSSION

Infuenza occurs in seasonal epidemics affecting mainly

those with extremes of ages (<6 months or >65 years) or

with comorbid medical illness. About 80% of infuenza

deaths and most severe disease are attributable to H3N2

strains of infuenza A.

5

In early months of 2009, a novel

H1N1 infuenza A virus descendent of the 1918 pandemic

strain, appeared in Mexico.

3

It was suffciently different

from previously circulating seasonal H1N1 viruses to

qualify as an antigenic shift and its resultant spread

around the world has been classifed as 2009 fu pandemic.

This new strain of H1N1 infuenza A virus is known as

pandemic H1N1 or pH1N1, novel H1N1, SOIV (swine

origin infuenza virus) or swine fu.

Infuenza epidemics due to seasonal strain used to occur

as a result of minor changes in the antigenic characteristics

of the hemaglutinin and neuraminidase glycoproteins

of the infuenza viruses (antigenic drift).

6

Morbidity and

mortality associated with seasonal infuenza outbreaks are

signifcant, especially in older patients.

5

However, infuenza

pandemics like that of swine fu, occur less frequently due

to major changes of surface glycoproteins of the viruses

(antigenic shift). Groups at risk of getting affected with

swine fu include those with underlying cardio-pulmonary

disease, having immunosuppression, pregnancy, lactation,

diabetes, obesity or neurological disabilities.

7

The clinical

features of uncomplicated infuenza are that of other

respiratory viral infections.

Majority of the morbidity and mortality due to swine fu are

attributable to pneumonia and the acute respiratory distress

syndrome (ARDS).

8

Pneumonia may be primary viral or

mixed viral and secondary bacterial. Those progressing

to ARDS have the worst prognosis.

8

Secondary bacterial

infection is much more prevalent in swine fu affected

patients than their seasonal counterpart. A study on

lung specimens from 77 fatal cases of pH1N1 infection

found 29% prevalence of bacterial superinfection and

Pneumococcus, Staphyococcus aureus, and Streptococcus

pyogenes being the commonest.

4

However, Klebsiella superinfection in a swine fu patient is a

rare fnding. To the best of our present knowledge, it is the

frst case report of swine fu superinfected with carbapenem

resistant Klebsiella. Carbapenemase producing bacteria are

often referred to as superbugs because infections caused

by them are diffcult to treat. Sometimes, such bacteria

are sensitive to polymyxins or tigecycline

9

(in our case,

it was sensitive to colistin and intermediately sensitive

to tigecycline). In 2009, a Swedish national travelling

India, developed UTI (urinary tract infection) caused by

carbapenem resistant Klebsiella sensitive to tigecycline

and colistin. After genotypic analysis of the isolate, a new

strain was found which is known today as NDM-1 or New

Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-1.

10

Unfortunately in our

case, genotypic analysis could not be done.

Hazra, et al.: Swine fu with carbapenem resistant Klebsiella

122 Asian Journal of Medical Sciences | Jul-Sep 2014 | Vol 5 | Issue 3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors like to acknowledge Infectious Disease and

Beliaghata General (ID & BG) Hospital, Kolkata, India

for providing necessary support. None of the authors has

any confict of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Jafri SSI, Ilyas M and Idrees M. Swine fu: A threat to human

health. Biotechnology and Mol Biol 2010; 5(3):46-50.

2. Myers KP, Olsen CW and Gray GC. Cases of swine infuenza

in humans: a review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 2007;

44(8):1084-1088.

3. Zimmer SM and Burke DS. Historical perspective Emergence

of infuenza A (H1N1) Viruses. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:

279-285.

4. Bacterial coinfections in lung tissue specimens from fatal

cases of 2009 pandemic infuenza A (H1N1) - United

States, May-August 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep

2009;58:1071-1074.

Authors Contribution:

RH & MSM Prepared the initial draft. RH, MBM, SC, KG Contributed to the manuscript. RH Reviewed and helped in fnal preparation

of the manuscript.

Source of Support: Nil, Confict of Interest: None declared.

5. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Bridges

CB, Cox NJ, et al. Infuenza-associated hospitalizations in the

United States. JAMA 2004; 292:13331340.

6. Lai CJ, Markoff LJ, Sveda MM, Lamb RA, Dhar R and Chanock

RM. Genetic variation of infuenza A viruses as studied by

recombinant DNA techniques. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1980; 354:162-

171.

7. Hospitalized patients with novel infuenza A (H1N1) virus

infection - California, April-May 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly

Rep 2009; 58:536-541.

8. Rello J, Rodrguez A, Ibaez P, Socias L, Cebrian J, Marques

A, et al. H1N1 SEMICYUC Working Group. Intensive care adult

patients with severe respiratory failure caused by Infuenza A

(H1N1)v in Spain. Crit Care Med 2009;13:148.

9. Health Protection Agency. Multi-resistant hospital bacteria

linked to India and Pakistan. Health Protection Report 2009;

3. Available from: http://www.hpa.org.uk/hpr/archives/2009/

news2609.htm.

10. Yong D, Toleman MA, Giske CG, Cho HS, Sundman K, Lee

K and Walsh TR. Characterization of a new metallo-beta-

lactamase gene, bla(NDM-1), and a novel erythromycin

esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella

pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India. Antimicrob Agents

Chemother 2009; 53(12):50465054.

You might also like

- Assignment 7Document2 pagesAssignment 7rajdiphazraNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3: Literature Review: 1 PointDocument3 pagesAssignment 3: Literature Review: 1 Pointrajdiphazra0% (1)

- Assignment 5Document2 pagesAssignment 5rajdiphazraNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2: Formulating Research Question: 1 PointDocument2 pagesAssignment 2: Formulating Research Question: 1 PointrajdiphazraNo ratings yet

- Assignment 4Document3 pagesAssignment 4rajdiphazraNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1Document2 pagesAssignment 1rajdiphazraNo ratings yet

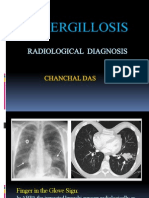

- Aspergillosis: Radiological DiagnosisDocument12 pagesAspergillosis: Radiological DiagnosisrajdiphazraNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Defence Mechanism of Oral CavityDocument15 pagesDefence Mechanism of Oral CavityANUBHANo ratings yet

- Diuretics: Dr. Sadat MemonDocument28 pagesDiuretics: Dr. Sadat MemonCham PianoNo ratings yet

- The Current Strategy in Hormonal and Non-HormonalDocument25 pagesThe Current Strategy in Hormonal and Non-HormonalJulio YulitaNo ratings yet

- PneumoniaDocument41 pagesPneumoniapaanar100% (2)

- Daftar Pustaka: Universitas Sumatera UtaraDocument3 pagesDaftar Pustaka: Universitas Sumatera UtaraYuliana WiralestariNo ratings yet

- Case Study MiDocument23 pagesCase Study Mianamika sharma100% (6)

- Pediatric Mechanical VentilationDocument36 pagesPediatric Mechanical VentilationrizalNo ratings yet

- Head To Toe Exam: ChestDocument2 pagesHead To Toe Exam: Chestnicolas lastreNo ratings yet

- AvantGen Awarded Contract From NIH To Expedite The Commercialization of Its AccuRate COVID-19 SelfCheck OTC TestDocument3 pagesAvantGen Awarded Contract From NIH To Expedite The Commercialization of Its AccuRate COVID-19 SelfCheck OTC TestPR.comNo ratings yet

- Hem OccultDocument2 pagesHem OccultfidofidzNo ratings yet

- Rectum: Malueth AbrahamDocument19 pagesRectum: Malueth AbrahamMalueth AnguiNo ratings yet

- Phacoemulsification Versus Small Incision Cataract Surgery (SICS) A Surgical Option For Immature Cataract in Developing Countries.Document5 pagesPhacoemulsification Versus Small Incision Cataract Surgery (SICS) A Surgical Option For Immature Cataract in Developing Countries.Ragni MishraNo ratings yet

- Facial Feminization Surgery FFS Surgeon ListingsDocument46 pagesFacial Feminization Surgery FFS Surgeon ListingsTrinity Rose Transsexual100% (2)

- 1 - Pharmaceutical Dosage FormsDocument41 pages1 - Pharmaceutical Dosage Formspanwar_brossNo ratings yet

- Disorders of The Eye LidsDocument33 pagesDisorders of The Eye Lidsc/risaaq yuusuf ColoowNo ratings yet

- Acute Otitis Media: Jama Patient PageDocument1 pageAcute Otitis Media: Jama Patient PageS. JohnNo ratings yet

- Physiotherapy in Shoulder Impigement SyndromeDocument181 pagesPhysiotherapy in Shoulder Impigement SyndromePraneeth KumarNo ratings yet

- MDI Major Depression Inventory - English PDFDocument3 pagesMDI Major Depression Inventory - English PDFcmenikarachchiNo ratings yet

- Test Preparation & ReviewDocument4 pagesTest Preparation & Reviewhelamahjoubmounirdmo100% (1)

- NICU 2021clinical Reference Manual For Advanced Neonatal Care FINALDocument254 pagesNICU 2021clinical Reference Manual For Advanced Neonatal Care FINALTewodros Demeke100% (7)

- Orthopaedic vs Orthodontic TherapyDocument3 pagesOrthopaedic vs Orthodontic Therapyاسراء فاضل مصطفى100% (1)

- Tool Box Talk - Snake BitesDocument1 pageTool Box Talk - Snake BitesNicole AnthonyNo ratings yet

- Bip03051f UgDocument2 pagesBip03051f UgdellalalaNo ratings yet

- CKHA 2013 Salary DisclosureDocument2 pagesCKHA 2013 Salary DisclosureChatham VoiceNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular System Lecture 1 2020 2021Document5 pagesCardiovascular System Lecture 1 2020 2021olawandeilo123No ratings yet

- Circulation Case Study Week 4Document10 pagesCirculation Case Study Week 4Caroline GamboneNo ratings yet

- Free TOEFL Practice Questions About The TOEFLDocument39 pagesFree TOEFL Practice Questions About The TOEFLDieu-Donné NoukounwouiNo ratings yet

- EFM Teaching Didactic FINALDocument81 pagesEFM Teaching Didactic FINALNadia RestyNo ratings yet

- St. Paul College of Ilocos Sur Nursing Department Clinical CourseDocument3 pagesSt. Paul College of Ilocos Sur Nursing Department Clinical CourseMarie Kelsey Acena Macaraig100% (1)

- Antibodies To Watch in 2020 PDFDocument25 pagesAntibodies To Watch in 2020 PDFFranciscoNo ratings yet