Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Health-Related Quality of Life After Ischemic Stroke: The Impact of Pharmaceutical Interventions On Drug Therapy (Pharmaceutical Care Concept)

Uploaded by

Dhila- Nailatul Fadhilah0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views7 pagesjnjnjmn

Original Title

1477-7525-8-59

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentjnjnjmn

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views7 pagesHealth-Related Quality of Life After Ischemic Stroke: The Impact of Pharmaceutical Interventions On Drug Therapy (Pharmaceutical Care Concept)

Uploaded by

Dhila- Nailatul Fadhilahjnjnjmn

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 7

Hohmann et al.

Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2010, 8:59

http://www.hqlo.com/content/8/1/59

Open Access RESEARCH

2010 Hohmann et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in

any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Research

Health-Related Quality of Life after Ischemic Stroke:

The Impact of Pharmaceutical Interventions on

Drug Therapy (Pharmaceutical Care Concept)

Carina Hohmann*

1,2

, Roland Radziwill

2

, Juergen MKlotz

1

and Andreas H Jacobs

3

Abstract

Background: Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) after stroke is an important healthcare measure. Pharmaceutical

Care (PC) is an evolving concept to optimize drug-therapy, minimize drug-related problems, and improve HRQoL of

patients. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of PC on HRQoL, as determined by Short Form 36 (SF-

36) among patients after TIA or ischemic stroke one-year following their initial entry in hospital.

Methods: Patients were assigned to either an intervention (IG) or a control group (CG). The individual assignment of

the patient to IG or CG depended on the community pharmacy to which the patients were assigned for care.

Community pharmacies either delivered standard care (CG) or provided intensified PC (IG). Pharmacists who are

members of the "Quality Assurance Working Group" (QAWG) provided PC for patients in IG.

Results: 255 patients were recruited (IG: n = 90; CG: n = 165) between 06/2004 to 01/2007. During the study, the

HRQoL of the patients in IG did not change significantly. In the CG, a significant decrease in the HRQoL was observed in

7/8 subscales and in both summary measures of SF-36.

Conclusions: This is the first follow-up study in Germany involving a major community hospital, rehabilitation

hospitals, community pharmacies and general practitioners investigating the impact of PC on HRQoL of patients after

ischemic stroke. Our findings indicate that an intensified education and care of patients after ischemic stroke by

dedicated pharmacists based on a concept of PC may maintain the HRQoL of IG patients.

Background

Stroke is one of the leading causes of death in Europe and

the major cause of disability in the elderly [1,2]. Health-

related quality of life (HRQoL) related to stroke and life

satisfaction after stroke are important healthcare out-

comes that have not received sufficient attention in the

literature. HRQoL assessment includes at least 4 dimen-

sions: physical, functional, psychological, and social

health [3,4]. The physical health dimension refers to dis-

ease-related symptoms. The functional health comprises

self-care, mobility, and the capacity to perform various

familiar and work roles. The psychological dimension

includes cognitive and emotional functions and subjec-

tive perceptions of health and life satisfaction. The social

dimension includes social and familiar contacts [3]. Short

Form 36 is a widely and frequently used, generic, patient-

report instrument for measuring quality of life [5]. It has

also been validated in patients with stroke [5,6].

Pharmaceutical Care (PC), first outlined by Hepler and

Strand in 1990, has been the subject of intensive research

in Germany for several years. PC is the provision of drug

therapy by a responsible pharmacist for the purpose of

achieving a definite outcome to improve the patients'

quality of life [7]. PC is a patient-tailored, outcome ori-

ented pharmacy practice that requires that the pharma-

cist work in concert with the patient and the patient's

other healthcare providers to promote health, to prevent

disease, and to assess, monitor, initiate, and modify medi-

cation use to assure that drug therapy regimens are safe

and effective. Thus, PC is a concept to optimize drug

therapy, minimize drug-related problems, and improves

self-management; it can directly affect the HRQoL of

patients. The pharmacist is a part of the health care team,

* Correspondence: carina.hohmann@klinikum-fulda.de

1

Klinikum Fulda gAG, Department of Neurology, Pacelliallee 4, 36043 Fulda,

Germany

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

Hohmann et al. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2010, 8:59

http://www.hqlo.com/content/8/1/59

Page 2 of 7

and extensive communication between pharmacist, phy-

sician, and the patient is necessary to achieve a defined

health care outcome [7]. The goal of Pharmaceutical Care

is to optimize the patient's HRQoL, and achieve positive

clinical outcomes, within realistic economic expendi-

tures. The positive influence of PC on HRQoL has been

demonstrated in several trials [8,9].

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the

impact of PC on the HRQoL, as determined by Short

Form 36 (SF-36) among patients after TIA or ischemic

stroke one-year following their initial entry into the hos-

pital.

Methods

Setting

A major community hospital in Germany (Klinikum

Fulda gAG), several rehabilitation hospitals, community

pharmacies and general practitioners were involved in

this study. The Stroke Unit of the Klinikum Fulda gAG

serves diagnosis and treatment of over 700 patients with

acute stroke each year.

Patients

Patients with TIA or ischemic stroke with a Barthel index

of over 30 points at the time of discharge from the hospi-

tal and living at home were included between June 2004

and January 2007. The follow-up-period for the patients

was 12 months. Demographic and clinical data were col-

lected from medical records and by interview.

The patients were assigned either to an intervention

group (IG) or a control group (CG). The individual

assignment of the patient to the IG or CG depended on

the community pharmacy to which patients were

assigned for care. Pharmacists (n = 23) who are members

of the "Quality Assurance Working Group" (QAWG) pro-

vided PC for patients in the IG. Pharmacists of the

QAWG met on a regular basis (once a month) to discuss

specific drug-related issues and to ensure proper imple-

mentation of PC in their pharmacies. The PC process in

this study comprises medication reviews and counselling

interviews with regards to medicines, especially those for

secondary prevention, and to specific actions, side

effects, and drug-interactions as well as cardiovascular

risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and

hyperlipidemia. Hypertension remains a major modifiable

risk factor for cardiovascular diseases. The diagnosis of

hypertension is made when the average of two or more

diastolic blood pressure (BP) measurements on at least

two subsequent visits is more than 90 mm Hg or when

the average of multiple systolic BP readings on two or

more subsequent visits is consistently more than 140 mm

Hg [10]. Diabetes mellitus is a group of metabolic dis-

eases characterised by chronic hyperglycemia resulting

from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both

[11]. Hyperlipidemia is defined as an abnormal plasma

lipid status. Common lipid abnormalities include ele-

vated levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein

(LDL) cholesterol, lipoprotein (a), and triglyceride; as well

as low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) choles-

terol. These abnormalities can be found alone or in com-

bination [12]. Furthermore, the pharmacists had to detect

and solve drug-related problems (DRPs). The community

pharmacists received education and training in PC with

respect to patients with stroke in several workshops. Top-

ics included causes of stroke, risk factors, symptoms, def-

inition of PC, identifying and solving DRPs and designing

a PC plan. Risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes

mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and atrial fibrillation as well as

secondary prevention and individual patient problems

were discussed. The other community (control) pharma-

cists (n = 39) delivered standard care for the patients

within the CG.

Pharmaceutical Care

The PC process for the patients in the IG consists of three

sections:

(i) At hospital: Patients and their relatives received a

counselling interview from the clinical pharmacist

about the current medication, their effects, the dos-

age and important side effects as well as administra-

tion advice. A medication record with detailed

information about the drug name, the dosage and

administration advice was provided.

(ii) Seamless care: At the time of discharge from hos-

pital, the general practitioner, the rehabilitation hos-

pital, and the community pharmacist received a

detailed care plan for the patient from the clinical

pharmacist.

(iii) In the ambulatory setting: PC was continued by

the attending pharmacist for 12 months during this

study. At least one counselling interview between the

pharmacist and the patient every three months was

obligatory. The attending pharmacist was required to

document the medication, the DRPs and the counsel-

ling interview.

Standard Care

Patients of the CG received a medication record at the

time of discharge from hospital and received standard

care from their community pharmacy. There is no

defined standard care process for the community phar-

macy and it depends on each pharmacist. General issues

are for example dispensing medicine, giving advice on

medicine, and information about side effects and drug-

interactions.

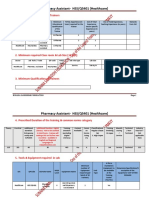

The steps taken over 12 months of the study are sum-

marized in Figure 1.

Hohmann et al. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2010, 8:59

http://www.hqlo.com/content/8/1/59

Page 3 of 7

Health-related quality of life

To evaluate the patient's HRQoL, the SF-36 was used

upon entry into the hospital and after 12 months. It pro-

vides a valid, subjective measure of physical and mental

health after stroke. Two types of SF-36 scores can be gen-

erated: the 8 SF-36 scales provide a comprehensive profile

of health status, and the two summary measures have fea-

tures that make them more advantageous for clinical tri-

als [5]. The SF-36 consists of 8 subscales: physical

functioning (PF), physical role (RP), bodily pain (BP),

general health (GH), vitality (VT), social functioning

(SF), emotional role (RE), and mental health (MH), and

the 2 summary measures are the Physical Component

Summary (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary

score (MCS).

Subscales and the summary scores range from 0 to 100,

with higher values representing better quality of life.

Different sociodemographic and medical variables were

recorded, including age, sex, cerebrovascular risk factors,

the type of cerebral ischemia (transient ischemic attack

(TIA), or ischemic stroke), and the Barthel Index.

The study was conducted in compliance with the

requirements of the institutional review board, Philipps

University, Marburg (Germany). All patients signed the

informed consent.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed by SPSS version

12.0 for Windows. Sample size calculations targeting a

power of 80% (2-sided test of = 5%) to improve the

patient's HRQoL after stroke on the basis of PC demon-

strated that 116 patients were needed for each group.

The evaluation of the HRQoL was based on a "per-pro-

tocol" analysis; only those patients were analyzed who

completed the entire trial.

Data are shown as means. The chi-squared test was

used for assessing differences in proportions. The stu-

dents t-test was used to compare the means of both

groups. In order to determine the normal distribution of

the variables the Kolmogorov-Smirnov-test was used.

The non-parametric rank-sum test according to Mann

and Whitney was used to compare the distribution of

ranks between the groups. The Wilcoxon Rank sum test

was chosen to identify differences in each group at base-

line and after 12 months. A two-tailed probability value

of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Over the entire period of enrolment (20 months), 1316

patients were admitted to the Stroke Unit. In total, 911

patients (69.2%) were excluded from the study due to

intracranial haemorrhage or other diagnoses, for example

migrainous aura, seizures, Barthel index < 30 points at

discharge from hospital, fatal ischemic stroke or living in

a nursing home. A total of 405 patients met the inclusion

criteria, 150 patients of these (37.0%) declined participa-

tion in the study. Reasons for refusal were an excellent

support by the family or general practitioner, no need for

further information or intensive care, or the patient was

not familiar with PC. Of the remaining 255 patients, n =

90 were recruited into IG and n = 165 into CG (Figure 2).

Patients' baseline characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. Between IG and CG, there were no significant

differences with regards to age (p = 0.952), sex (p = 0.554)

or subtype of cerebral ischemia (p = 0.814), and Barthel

Index (p = 0.101). The most frequent cardiovascular risk

factor in both groups was arterial hypertension (37%); the

second most frequent was a combination of hypertension

and hyperlipidemia.

During the study period 17 patients (18.9%) in the IG

and 8 patients (4.9%) in the CG were lost during follow-

up. Reasons for patients' drop-out were withdrawal from

informed consent, moving of the patient to another town,

transfer to a nursing home or no specific reasons. One

patient in the IG and five patients in the CG died (Figure

2). No differences in sex, ages, and diagnosis were found

in both groups at time of discharge from hospital.

Figure 1 The sequence and structure in the intervention and con-

trol group for 12 months.

Intervention group (IG) Control group (CG)

Individual assignment to IG or CG depended on the community

pharmacy to which the patients were assigned for care

medication review process

patients health-related quality of life (SF-36)

medication record

Stroke Unit /

neurological

ward

counselling interview

Seamless

care

Care plan for the community

pharmacy, rehabilitation hospi-

tal and general practitioner from

the clinical pharmacist

Community

pharmacy

Pharmaceutical Care

medication review process

counselling interview (secon-

dary prevention, cardiovascular

risk factors and their medicines)

Detecting and solving drug-

related problems

Standard Care (it depends on

the pharmacist in the commu-

nity pharmacy

After 12

months

patients health-related quality of life (SF-36)

Hohmann et al. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2010, 8:59

http://www.hqlo.com/content/8/1/59

Page 4 of 7

Health-related quality of life

Eight subscales

The distribution of SF-36 scores in the IG (n = 64) and in

the CG (n = 119) is shown in Figure 3, 4, 5, 6. Upon

admission patients of both, IG and CG, groups showed

no significant differences in the 8 subscales (Figure 3).

After 12 months, the subscale vitality was significantly

lower in CG patients than in IG patients (p = 0.027) (Fig-

ure 4).

The HRQoL of patients in IG remained stable over the

entire observation period. Only the subscale bodily pain

decreased significantly over time (p = 0.001) (Figure 5). In

contrast, HRQoL parameter of patients in CG deterio-

rated significantly in 7 of the 8 subscales over time (Fig-

ure 6).

Two summary measures

The mean scores of both summary measures, PCS and

MCS, are shown in Table 2. Upon entry into the study

Figure 3 Score distribution of the SF-36 (8 subscales) IG and CG at

hospital (mean and standard deviation).

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

PF RP BP GH VT SF RE MH

m

e

a

n

IG (hospital) CG (hospital)

Figure 4 Score distribution of the SF-36 (8 subscales) IG and CG

after 12 months (mean and standard deviation).

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

PF RP BP GH VT SF RE MH

m

e

a

n

IG (12 months) CG (12 months)

*

Figure 2 Flow chart for patients' inclusion and exclusion criteria

and their participation.

A total of 1316 patients were admitted to the stroke unit

Excluded (n=1061)

- inclusion criteria not met

(n=911)

- declined the participation

(n=150)

Included (n=255)

Intervention group (n=90) Control group (n=165)

Lost to follow-up (n=17):

- withdraw from informed-consent

(n=12)

- moving to another town (n=1)

- transfer to a nursing home (n=2)

- no specific reason (n=2)

death (n=1)

Lost to follow up (n=8):

- withdraw from informed consent

(n=1)

- moving to another town (n=1)

- transfer to a nursing home (n=2)

- no specific reason (n=4)

death (n=5)

Outcome data Outcome data

Table 1: Baseline characteristics

Characteristics Interventio

n Group

n = 90

Control

Group

n = 165

Age, mean SD (years) 68.2 ( 9.7) 68.1 ( 10.8)

Min 45 23

Max 85 85

Sex, n (%)

female 35 (38.9%) 58 (35.2%)

male 55 (61.1%) 107 (64.8%)

subtype of cerebral ischemia, n (%)

TIA 28 (31.1%) 49 (29.7%)

Ischemic stroke 62 (68.9%) 116 (70.3%)

Barthel Index, mean SD 92,8 ( 7,5) 89,4 ( 14,3)

cardiovascular risk factors

hypertension 33 (36.7%) 61 (37.0%)

hyperlipidemia 6 (6.7%) 5 (3.0%)

diabetes mellitus 1 (1.1%) 2 (1.2%)

hypertension+hyperlipidemia 31 (34.4%) 46 (27.9%)

hypertension+diabetes mellitus 4 (4.4%) 20 (12.1%)

diabetes

mellitus+hyperlipidemia

-- 2 (1.2%)

hypertension+diabetes

mellitus+hyperlipidemia 7 (7.8%) 15 (9.1%)

None 8 (8.9%) 14 (8.5%)

SD = Standard deviation

Hohmann et al. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2010, 8:59

http://www.hqlo.com/content/8/1/59

Page 5 of 7

there was no significant difference in the two summary

measures in either group. At follow-up, there were also

no significant differences in HRQoL between the groups

(Table 2). For the CG, a significant decline in PCS and

MCS was observed between baseline and at follow-up

(PCS: p = 0.023; MCS: p = 0.001). For the IG, changes in

PCS and MCS between study entry and at follow-up were

not statistically significant.

Discussion

This is the first study in Germany to investigate the

impact of intensive pharmaceutical care (PC) versus stan-

dard care in a larger patient population with ischemic

stroke. This study demonstrates that PC is able to prevent

deterioration of most HRQoL parameters over a 12

months period. Our findings indicate that PC as per-

formed in the hospital and in the community setting is

feasible and has a clear benefit and positive impact on

patient's HRQoL. Moreover, this study is a step forward

towards monitoring the implementation of PC within

hospitals and within the community setting and towards

evaluating the role of pharmacists within a specific thera-

peutic team. We found that a PC concept stabilizes the

HRQoL in several scales as a result of an intensified

involvement by pharmacists.

In a comparison of the subscales and the summary

measures in both groups upon study entry there were no

significant differences, thus providing an optimal starting

point for measuring the impact of PC on HRQoL. After

12 months the comparison of the HRQoL of the patients

who received intensified PC with those who received

standard care showed that the vitality of the patients in

CG was significantly lower than of patients in IG. The

other subscales and the summary measures showed

lower, but not significant, HRQoL scores in CG indicat-

ing inferior HRQoL as compared with the patients in IG.

Due to ethical considerations community pharmacies

were not restricted from delivering PC as it did not seem

appropriate to keep the control pharmacists from provid-

ing PC in the case that DRP became apparent. For this

reason the comparison may not to be statistically signifi-

cant.

Most importantly, there was a significant deterioration

of 7 of 8 subscales as well as both summary measures of

the HRQoL over the 12 months period in the CG. That

means that patients who do not receive intensified PC

have a higher chance of deteriorating HRQoL. For the IG,

there was only a significant deterioration in bodily pain at

follow up. The deterioration of the HRQoL in patients

with cerebrovascular diseases has been reported in previ-

ous trials in several parameters [3,13,14]. The quality of

the patient's recovery can be evaluated on the basis of the

activity of daily living (ADL), social activities, and return

to work. Independently of ADL significant deleterious

effects in HRQoL result from continuing loss of function

due to the stroke. The deterioration in the HRQoL can be

caused by the presence of anomalous perception and dis-

satisfaction in patients with minor disability levels that

were incompletely restored after the stroke. Thus, the

consequences of mild to moderate stroke can affect all

dimensions of HRQoL despite the patient achieving full

independence as measured in ADL [3].

By participating in this study the HRQoL of the patients

in the IG was stable in several subscales and both sum-

mary measures indicating that the HRQoL can be main-

tained by intensified PC. Several studies have also

demonstrated that PC may have a positive impact on the

patients' HRQoL for example in patients with asthma or

hypertension [8,15,16]. Graesel et al. investigated the

impact of an intensified transition concept between inpa-

tient neurological rehabilitation and home care of

patients with stroke. The intensified transition concept

included four additional elements: a psycho-educational

seminar for family carers; an individual training course

for carers; therapeutic weekend care at home before dis-

charge; and finally, telephone counselling three months

Figure 5 Score distribution of the SF-36 (8 subscales) IG in hospi-

tal and after 12 months (mean and standard deviation).

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

PF RP BP GH VT SF RE MH

m

e

a

n

IG (hospital) IG (12 months)

***

Figure 6 Score distribution of the SF-36 (8 subscales) CG in hospi-

tal and after 12 months (mean and standard deviation). PF: physi-

cal functioning. RP: physical role. BP: bodily pain. GH: general health. VT:

vitality. SF: social functioning. RE: emotional role. MH: mental health. *

= p < 0.05. ** = p < 0.01. *** = p < 0.001.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

PF RP BP GH VT SF RE MH

m

e

a

n

CG (hospital) CG (12 months)

***

***

*

***

*** **

**

Hohmann et al. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2010, 8:59

http://www.hqlo.com/content/8/1/59

Page 6 of 7

after discharge. The results show that this concept did

not lead to any significant benefit, neither to functional

status nor to HRQoL [17]. This finding may indicate that

the standard transition already contains effective ele-

ments of preparation for home care and that therefore no

further decisive advantage can be attained. Otherwise the

number of patients (n = 62) as well as the observation

period (n = 6 months) in the study was limited, thus

excluding long-term effects.

The HRQoL of the patients in the CG decreased signif-

icantly in the subscales and in both summary measures.

The deterioration of the physical role was significant

while physical functioning did not significantly deterio-

rate, which may indicate that patients perceived a decline

in their physical conditions.

There is a large difference in the frequency of diabetes

mellitus in both groups (IG: n = 12 (= 13.3%); CG: n = 39

(= 23.6%)). Diabetes mellitus has detrimental effects on a

range of health outcomes including HRQoL; for example

people with diabetes have lower scores at the SF-36 [18].

Thus, the higher proportion of patients with diabetes in

the CG may possibly cause the deterioration of HRQoL.

It should be pointed out that a considerably higher pro-

portion of subjects in the IG than in the CG refused to

participate. Those patients who refused to participate had

comparable demographic data, but may have had more

medical, social or psychological problems which could

have affected the HRQoL. The difference in HRQoL after

one year could be due to selection bias.

The mortality rate in both groups seems to be remark-

ably low (IG: n = 1; CG: n = 5); which is due to the fact

that patients with a Barthel index of less than 30 points at

discharge from hospital and/or who live in a nursing

home were excluded from this study. These exclusion cri-

teria were defined because only patients mobile enough

to go the pharmacy can be given PC.

An important difficulty in the analysis of HRQoL in

stroke patients is that few studies use the same measure-

ment tools and the same period of follow up. Further-

more, there are no data in the literature from the patients'

HRQoL from before the cerebrovascular event.

Limitations

The limitations of the present study include the fact that

no blinding or randomization could be performed. A tar-

get number of 116 participants were calculated for each

group. However, only 90 patients could be recruited for

the IG, as many patients refused to participate. The time

of enrolment was extended from 12 to 20 months and

then stopped. Moreover, patients who were lost to follow-

up were not evaluated for HRQoL, because no follow-up

data were available. It should be pointed out that, due to

ethical considerations, it did not seem to be appropriate

to keep the control pharmacists from caring in the case

that DRP became apparent. Furthermore, we did not have

any information on socioeconomic status, financial

resources or caregiver support in patients of either group,

which could have influenced the outcome of the patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this is the first follow-up study in Germany

involving a major community hospital, rehabilitation hos-

pitals, community pharmacies and general practitioners

demonstrating the potential impact of intensified phar-

maceutical care for patients with ischemic stroke on

HRQoL. Our findings indicate that an intensified educa-

tion and care of patients after ischemic stroke by dedi-

Table 2: Score distribution of the SF-36 (2 summary measures) at hospital and after 12 months (per-protocol-analysis)

IG (n = 64) CG (n = 119) After 12 months

Between group comparison

SF-36 Scales time mean

( SD)

mean

( SD)

p-Value

PCS Hospital 41.8 ( 9.8) 41.2 ( 10.8)

After 12 months 41.5 ( 11.0) 38.1 ( 11.6) 0.090

p-Value Differences between baseline and after

12 months

0.313 0.023*

MCS Hospital 49.5 ( 10.6) 49.6 ( 11.7)

After 12 months 48.1 ( 11.3) 45.0 ( 10.9) 0.077

p-Value Differences between baseline and after

12 months

0.831 0.001***

SD = Standard deviation.

= The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the distribution of ranks between the groups.

= The Wilcoxon Rank sum test was chosen to identify differences in each group at baseline and after 12 months.

Hohmann et al. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2010, 8:59

http://www.hqlo.com/content/8/1/59

Page 7 of 7

cated pharmacists based on a concept of PC may have a

positive impact on HRQoL.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CH has made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition

of data, analysis and interpretation of data. RR, and JMK have made substantial

contributions to conception and design. All authors have been involved in

interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for impor-

tant intellectual content and have given final approval of the version to be

published.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participating patients, community pharmacists and

physicans who supported our study. We would also like to thank the Foerderini-

tiative Pharmazeutische Betreuung e.V., Berlin, Germany and the Dr. August und Dr.

Anni Lesmueller Stiftung, Munich, Germany for funding this project.

Author Details

1

Klinikum Fulda gAG, Department of Neurology, Pacelliallee 4, 36043 Fulda,

Germany,

2

Klinikum Fulda gAG, Department of Pharmacy and Patient

Counselling, Pacelliallee 4, 36043 Fulda, Germany and

3

European Institute for

Molecular Imaging - EIMI, University of Muenster, Technologiehof L1,

Mendelstrasse 11, 48149 Muenster, Germany

References

1. Kolominsky-Rabas P, Sarti C, Heuschmann PU, Graf C, Siemonsen S,

Neundoerfer B, Katalinic A, Lang E, Gassmann KG, Ritter von Stockert T: A

prospective community-based study of stroke in Germany - The

Erlangen stroke project (ESPro) - Incidence and case fatality at 1, 3, and

12 months. Stroke 1998, 29:2501-2506.

2. Manolio TA, Kronmal RA, Burke GL, O'Leary DH, Price TH: Short-term

predictors of incident stroke in older adults: The Cardiovascular Health

study. Stroke 1996, 27:1479-1486.

3. Carod-Artal J, Egido JA, Gonzlez JL, de Seijas EV: Quality of life among

stroke survivors evaluated 1 year after stroke: Experience of a stroke

unit. Stroke 2000, 31:2995-3000.

4. de Haan R: Measuring quality of life after stroke using the SF-36. Stroke

2002, 33:1176-1177.

5. Hobart JC, Williams LS, Moran K, Thompson AJ: Quality of life

measurement after stroke: uses and abuses of the SF-36. Stroke 2002,

33:1348-1356.

6. Anderson C, Laubscher S, Burns R: Validation of the Short Form 36 (SF-

36) Health Survey questionnaire among stroke patients. Stroke 1996,

27:1812-1816.

7. Hepler CD, Strand LM: Opportunities and responsibilities in

pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm 1990, 47:533-543.

8. Schulz M, Verheyen F, Mhlig S, Mller JM, Mhlbauer K, Knop-

Schneickert E, Petermann F, Bergmann KC: Pharmaceutical Care Services

for Asthma patients: a controlled intervention study. J Clin Pharmaol

2001, 41:668-676.

9. Paulos CP, Nygren CEA, Celedon C, Carcamo CA: Impact of a

Pharmaceutical Care Program in a Community Pharmacy on Patients

with Dyslipidemia. Ann Pharmacother 2005, 39:939-943.

10. Carretero OA, Oparil S: Essential Hypertension: Part I: Definition and

Etiology. Circulation 2000, 101:329-335.

11. Craig ME, Hattersley A, Donaghue KC: Definition, epidemiology and

classification of diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatric Diabetes

2009, 10(Suppl 12):3-12.

12. Ballantyne CM, O'Keefe JH, Gotto AM: Overview of Atherosclerosis and

Dyslipidemia. In Dyslipidemia & Atherosclerosis Essentials Volume Chapter

1. Fourth edition. Physicians's Press. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett;

2009:5.

13. Suenkeler IH, Nowak M, Misselwitz B, Kugler C, Schreiber W, Oertel W, Back

T: Timecourse of health-related quality of life as determined 3, 6 and 12

months after stroke. Relationship to neurological deficit, disability and

depression. J Neurol 2002, 249:1160-1167.

14. Hackett ML, Duncan JR, Anderson CS, Broad JB, Bonita R: Health-related

quality of life among long-term survivors of stroke: results from the

Auckland Stroke Study, 1991-1992. Stroke 2000, 31:440-447.

15. Mangiapane S, Schulz M, Muhlig S, Ihle P, Schubert I, Waldmann H:

Community pharmacy-based pharmaceutical care for asthma patients.

Ann Pharmacother 2005, 39:1817-1822.

16. Cote I, Moisan J, Chabot I, Gregoire J-P: Health-related quality of life in

hypertension: impact of a pharmacy intervention programme. Journal

of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 2005, 30:355-362.

17. Graesel E, Biehler J, Schmidt R, Schupp W: Intensification of the transition

between inpatient neurological rehabilitation and home care of stroke

patients. Controlled clinical trial with follow-up assessment six months

after discharge. Clinical Rehabilitation 2005, 19:725-736.

18. Wee HL, Cheung YB, Li SC, Fong KY, Thumboo J: The impact of diabetes

mellitus and other chronic medical conditions on health-related

Quality of Life: Is the whole greater than the sum of its parts? Health

and Quality of Life Outcomes 2005, 3:2.

doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-59

Cite this article as: Hohmann et al., Health-Related Quality of Life after Isch-

emic Stroke: The Impact of Pharmaceutical Interventions on Drug Therapy

(Pharmaceutical Care Concept) Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2010, 8:59

Received: 8 March 2010 Accepted: 18 June 2010

Published: 18 June 2010

This article is available from: http://www.hqlo.com/content/8/1/59 2010 Hohmann et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2010, 8:59

You might also like

- MSC1551 NAC Asthma COPD Medications Chart 2018 HR InternalDocument1 pageMSC1551 NAC Asthma COPD Medications Chart 2018 HR InternalDisha Jalan100% (1)

- Bangladesh National Formulary (BDNF) 5th Version 2019 PDFDocument924 pagesBangladesh National Formulary (BDNF) 5th Version 2019 PDFMSKC78% (9)

- Reduce Modifiable Cardiac Risk Factors in AdultsDocument4 pagesReduce Modifiable Cardiac Risk Factors in AdultsevangelinaNo ratings yet

- Impact of PharmacistDocument5 pagesImpact of PharmacistLeny MeiriyanaNo ratings yet

- A Descriptive Study of Adherence To Lifestyle Modification Factors Among Hypertensive PatientsDocument23 pagesA Descriptive Study of Adherence To Lifestyle Modification Factors Among Hypertensive PatientsSt. KhodijahNo ratings yet

- 2 Effects of A Pharmaceutical Care Intervention Coronary Heart DiseaseDocument16 pages2 Effects of A Pharmaceutical Care Intervention Coronary Heart DiseaseRosalinda Marquez VegaNo ratings yet

- Patterns of Antihypertensive Drug Utilization in Primary CareDocument11 pagesPatterns of Antihypertensive Drug Utilization in Primary CareIvan LiandoNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of A Pharmaceutical Care Program For Hypertensive Patients in Rural PortugalDocument7 pagesEvaluation of A Pharmaceutical Care Program For Hypertensive Patients in Rural PortugalNOorulain HyderNo ratings yet

- Antihypertension Non AdherenceDocument16 pagesAntihypertension Non AdherencebezieNo ratings yet

- Annals of General PsychiatryDocument9 pagesAnnals of General PsychiatryPutu Agus GrantikaNo ratings yet

- Makalah KesehatanDocument9 pagesMakalah KesehatanNini RahmiNo ratings yet

- Approach by Health Professionals To The Side Effects of Antihypertensive Therapy: Strategies For Improvement of AdherenceDocument10 pagesApproach by Health Professionals To The Side Effects of Antihypertensive Therapy: Strategies For Improvement of AdherenceSabrina JonesNo ratings yet

- DeJonge P 2003Document6 pagesDeJonge P 2003Camila AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Science 6Document12 pagesScience 6Shinta Dian YustianaNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Patients' Knowledge and Medication Adherence Among Patients With HypertensionDocument8 pagesRelationship Between Patients' Knowledge and Medication Adherence Among Patients With HypertensionWina MariaNo ratings yet

- Effect On Blood Pressure of A Continued Nursing Intervention Using Chronotherapeutics For Adult Chinese Hypertensive PatientsDocument9 pagesEffect On Blood Pressure of A Continued Nursing Intervention Using Chronotherapeutics For Adult Chinese Hypertensive PatientsadeliadeliaNo ratings yet

- Impact of A Designed Self-Care Program On Selected Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing HemodialysisDocument18 pagesImpact of A Designed Self-Care Program On Selected Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing HemodialysisImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Hypertension Treatment Adherence ADocument7 pagesDeterminants of Hypertension Treatment Adherence ADr YusufNo ratings yet

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine As Part of Primary Health Care in GermanyDocument8 pagesComplementary and Alternative Medicine As Part of Primary Health Care in GermanyNancy KawilarangNo ratings yet

- JHH 20168Document8 pagesJHH 20168Anonymous bgcWQhRNo ratings yet

- 1471 2474 13 180 PDFDocument8 pages1471 2474 13 180 PDFDini BayuariNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument75 pagesResearchArun AhirwarNo ratings yet

- Identifying and Measuring Outcomes 6MN3hDocument16 pagesIdentifying and Measuring Outcomes 6MN3hYazeed AsrawiNo ratings yet

- Impact of Pharmacist Clinical Interventions On Treatment Outcomes in Hypertensive Patients An Outcomes StudyDocument6 pagesImpact of Pharmacist Clinical Interventions On Treatment Outcomes in Hypertensive Patients An Outcomes StudyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Asgedom2018 Article AntihypertensiveMedicationAdheDocument8 pagesAsgedom2018 Article AntihypertensiveMedicationAdhehendriNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia Treatment & Management - Approach Considerations, Antipsychotic Pharmacotherapy, Other PharmacotherapyDocument13 pagesSchizophrenia Treatment & Management - Approach Considerations, Antipsychotic Pharmacotherapy, Other PharmacotherapydilaNo ratings yet

- JJJGJHGJHGHDocument6 pagesJJJGJHGJHGHTaufik NurohmanNo ratings yet

- Article - The Devil Is in DetailDocument23 pagesArticle - The Devil Is in DetailHishamudin KadiranNo ratings yet

- Rubio Valera2013Document10 pagesRubio Valera2013Marcus Fábio leite AndradeNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Self-Efficacy and Quality of Life in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study From PalestineDocument13 pagesCardiac Self-Efficacy and Quality of Life in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study From Palestineشبلي غرايبهNo ratings yet

- RRL Hypertension ComplianceDocument30 pagesRRL Hypertension ComplianceAngelaTrinidadNo ratings yet

- M Ramirez Nurs660 TherapeuticstableDocument17 pagesM Ramirez Nurs660 Therapeuticstableapi-273459660No ratings yet

- Journal of Psychosomatic Research: M.C. Shedden-Mora, B. Groß, K. Lau, A. Gumz, K. Wegscheider, B. LöweDocument8 pagesJournal of Psychosomatic Research: M.C. Shedden-Mora, B. Groß, K. Lau, A. Gumz, K. Wegscheider, B. LöweSeva RenandoNo ratings yet

- Goudarzi 2020Document7 pagesGoudarzi 2020Herick Alvenus WillimNo ratings yet

- Bahan 2-DikonversiDocument11 pagesBahan 2-DikonversiMaya ismayaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal BING Kel 6Document11 pagesJurnal BING Kel 6Nisya Andesita HNo ratings yet

- Counseling Overweight Patients: Analysis of Preventive Encounters in Primary CareDocument7 pagesCounseling Overweight Patients: Analysis of Preventive Encounters in Primary CareAgil SulistyonoNo ratings yet

- HBM 3Document10 pagesHBM 3renzelpacleb123No ratings yet

- Polypill, Indications and Use 2.1Document12 pagesPolypill, Indications and Use 2.1jordiNo ratings yet

- PJMS 34 959Document5 pagesPJMS 34 959Husni FaridNo ratings yet

- The Determinants of Hypertension Awareness, Treatment, and Control in An Insured PopulationDocument7 pagesThe Determinants of Hypertension Awareness, Treatment, and Control in An Insured PopulationHugo Suarez RomeroNo ratings yet

- Psychological Interventions For The Management of Bipolar DisorderDocument9 pagesPsychological Interventions For The Management of Bipolar DisorderFausiah Ulva MNo ratings yet

- Validation of The Short Form of The Hypertension Quality of Life Questionnaire (MINICHAL)Document35 pagesValidation of The Short Form of The Hypertension Quality of Life Questionnaire (MINICHAL)Adi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Hypertension Control Programs in Occupational Settings: Yield Benefit, Pound Including 600,000 LeadingDocument6 pagesHypertension Control Programs in Occupational Settings: Yield Benefit, Pound Including 600,000 LeadingGrace LNo ratings yet

- Articles: Backgro UndDocument8 pagesArticles: Backgro UndHaryaman JustisiaNo ratings yet

- Coping Strategies and Blood Pressure Control Among Hypertensive Patients in A Nigerian Tertiary Health InstitutionDocument6 pagesCoping Strategies and Blood Pressure Control Among Hypertensive Patients in A Nigerian Tertiary Health Institutioniqra uroojNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Medication Adherence in Lebanese Hypertensive PatientsDocument11 pagesEvaluation of Medication Adherence in Lebanese Hypertensive PatientsDoddo IndrayanaNo ratings yet

- Diabetes ComparativosDocument9 pagesDiabetes ComparativosMarlon Salguedo MadridNo ratings yet

- Adherence To Hiv Treatment: Drug Adherence Counselling Programme DevelopmentDocument6 pagesAdherence To Hiv Treatment: Drug Adherence Counselling Programme DevelopmentmakmgmNo ratings yet

- HPCP Assignment 2Document8 pagesHPCP Assignment 2mokshmshah492001No ratings yet

- Study of Drug Use in Essential Hypertension and Their ComplianceDocument13 pagesStudy of Drug Use in Essential Hypertension and Their ComplianceRachmat MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Anty - Hypertensive Need A Change RegimenDocument4 pagesAnty - Hypertensive Need A Change RegimenSyifa MunawarahNo ratings yet

- Etminani 2020Document18 pagesEtminani 2020José Carlos Sánchez-RamirezNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument12 pagesResearch ArticletiarNo ratings yet

- Antidepressants and Health-Related Quality of Life For Patients With DepressionDocument14 pagesAntidepressants and Health-Related Quality of Life For Patients With Depressionjohndoe691488No ratings yet

- The Effects of Self-Management Education Tailored To Health Literacy OnDocument7 pagesThe Effects of Self-Management Education Tailored To Health Literacy OnDINDA PUTRI SAVIRANo ratings yet

- Journal Review Final PaperDocument10 pagesJournal Review Final Paperapi-464793486No ratings yet

- Jurnal Endokrin7Document8 pagesJurnal Endokrin7Anonymous a9Wtp0ArNo ratings yet

- BMC Cardiovascular DisordersDocument11 pagesBMC Cardiovascular DisordersjlventiganNo ratings yet

- Drug Adherence in Hypertension and Cardiovascular ProtectionFrom EverandDrug Adherence in Hypertension and Cardiovascular ProtectionMichel BurnierNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Risks from Prescription and Nonprescription Drugs: Mechanisms and Approaches to Risk ReductionFrom EverandDiabetes Risks from Prescription and Nonprescription Drugs: Mechanisms and Approaches to Risk ReductionNo ratings yet

- Finding the Path in Alzheimer’s Disease: Early Diagnosis to Ongoing Collaborative CareFrom EverandFinding the Path in Alzheimer’s Disease: Early Diagnosis to Ongoing Collaborative CareNo ratings yet

- Patient With Intra-Cranial Mass.: 3.1a. Pre-Contrast Axial T1 WTD MRI 3.1b. Post-Contrast Axial T1 WTD MRIDocument11 pagesPatient With Intra-Cranial Mass.: 3.1a. Pre-Contrast Axial T1 WTD MRI 3.1b. Post-Contrast Axial T1 WTD MRIDhila- Nailatul FadhilahNo ratings yet

- Ispei (: Klinik NnuroiogiDocument12 pagesIspei (: Klinik NnuroiogiDhila- Nailatul FadhilahNo ratings yet

- Level 2 Lesson 1: Future TenseDocument3 pagesLevel 2 Lesson 1: Future Tensedomon46No ratings yet

- Presentation Title: Subheading Goes HereDocument2 pagesPresentation Title: Subheading Goes HereDhila- Nailatul FadhilahNo ratings yet

- Projects Documents Team Links What's New: Insert Workgroup Logo On Slide MasterDocument2 pagesProjects Documents Team Links What's New: Insert Workgroup Logo On Slide MasterDhila- Nailatul FadhilahNo ratings yet

- DISPENSINGmanual Act. 2Document4 pagesDISPENSINGmanual Act. 2sybyl formenteraNo ratings yet

- Cotizacion Farmacia 17.08.2022Document48 pagesCotizacion Farmacia 17.08.2022Alicia OrtizNo ratings yet

- Pharmacy Assistant-HSS/Q5401 (Healthcare) : 1. Minimum Qualification For TrainersDocument7 pagesPharmacy Assistant-HSS/Q5401 (Healthcare) : 1. Minimum Qualification For TrainersBabar AliNo ratings yet

- TS Circ02 2015 PDFDocument22 pagesTS Circ02 2015 PDFAnonymous 9NlQ4n2oNo ratings yet

- M.pharm SyllabusDocument47 pagesM.pharm SyllabustusharphaleNo ratings yet

- Generic Name of Medicine (With Dosage Form and Strength) Brand Quantity Total Cost Supplier Manufacturer Acquisition CST Per UnitDocument72 pagesGeneric Name of Medicine (With Dosage Form and Strength) Brand Quantity Total Cost Supplier Manufacturer Acquisition CST Per UnitAlex SibalNo ratings yet

- Evaluation Enzyme Inhibitors Drug Discovery PDFDocument2 pagesEvaluation Enzyme Inhibitors Drug Discovery PDFKarlaNo ratings yet

- Applications of Communication Skills in Patient Care ServicesDocument2 pagesApplications of Communication Skills in Patient Care ServicesPooja agarwalNo ratings yet

- Module Health CLB 4 Going To PharmacyDocument4 pagesModule Health CLB 4 Going To PharmacyDanniNo ratings yet

- Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier SystDocument1 pageCrit Rev Ther Drug Carrier SystBiswarup DasNo ratings yet

- PHAR 7633 Chapter 15 Multiple Oral Dose Administration: CP EquationDocument4 pagesPHAR 7633 Chapter 15 Multiple Oral Dose Administration: CP EquationSonia BaruaNo ratings yet

- Midterm Exam Reviewer: Surgical Handwashing QuizDocument9 pagesMidterm Exam Reviewer: Surgical Handwashing QuizOfficially RandomNo ratings yet

- Paarenteral ProductionDocument32 pagesPaarenteral ProductionHanuma KanthetiNo ratings yet

- Brochure 3rd World Congress On Pharmacology and Clinical TrialsDocument9 pagesBrochure 3rd World Congress On Pharmacology and Clinical TrialsbapaknyanadlirNo ratings yet

- Tgs Tgsan PKL - Copy BEnar BeDocument129 pagesTgs Tgsan PKL - Copy BEnar BeLuqiNo ratings yet

- InnovaDocument29 pagesInnovasanjay_gawaliNo ratings yet

- Final Pico Question InformaticsDocument5 pagesFinal Pico Question Informaticsapi-310396820No ratings yet

- Recent Advances in The Development of Anti-Tuberculosis Drugs Acting On Multidrug-Resistant Strains: A ReviewDocument18 pagesRecent Advances in The Development of Anti-Tuberculosis Drugs Acting On Multidrug-Resistant Strains: A Reviewmalik003No ratings yet

- Scale Up and Postapproval Changes (Supac) Guidance For Industry: A Regulatory NoteDocument9 pagesScale Up and Postapproval Changes (Supac) Guidance For Industry: A Regulatory NoteAKKAD PHARMANo ratings yet

- Pharma Entrepreneurship - Guidlines For Developing Pharma EntrepreneurshipDocument96 pagesPharma Entrepreneurship - Guidlines For Developing Pharma EntrepreneurshipkandyjoshiNo ratings yet

- Work Immersion Portfolio: Jhon Carlo Cera CatindoyDocument22 pagesWork Immersion Portfolio: Jhon Carlo Cera CatindoyJoel DufaleNo ratings yet

- List of Substandard Drugs2008Document8 pagesList of Substandard Drugs2008Mohammad Shahbaz AlamNo ratings yet

- Registered Medicine List 2014 FMHACADocument162 pagesRegistered Medicine List 2014 FMHACASindy ElfasNo ratings yet

- FDA Foia Log - May 2019Document56 pagesFDA Foia Log - May 2019Faiz RasoolNo ratings yet

- Pharmacy Business Plan - Executive SummaryDocument4 pagesPharmacy Business Plan - Executive SummaryI.k sidneyNo ratings yet

- A2. Syringe Labelling Critical AreasDocument34 pagesA2. Syringe Labelling Critical AreasAyusafura MuzamilNo ratings yet

- BCS 1 1 PDFDocument38 pagesBCS 1 1 PDFHely PatelNo ratings yet

- Abdi Ibrahim 02Document3 pagesAbdi Ibrahim 02jj_kkNo ratings yet