Professional Documents

Culture Documents

FD

Uploaded by

Christian JaraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

FD

Uploaded by

Christian JaraCopyright:

Available Formats

Factitious diarrhea

Author

Arnold Wald, MD

Section Editor

Lawrence S Friedman, MD

Deputy Editor

Shilpa Grover, MD, MPH

Disclosures

All topics are updated as new evidence becomes available and our peer review pro

cess is complete.

Literature review current through: Nov 2013. | This topic last updated: Jun 24,

2013.

INTRODUCTION The term factitious (or factitial) has been used in medical parlance

to imply covert human activity. The consideration of such a possibility often c

hanges the patient-physician relationship, leading the physician to feel deceive

d and the patient to feel mistrusted. However, the pejorative connotation with w

hich factitious illness has been encumbered requires softening because some pati

ents with factitious disease suffer through no fault of their own. (See "Factiti

ous disorder and Munchausen syndrome".)

When a thorough search for the etiology of an illness is unrevealing, the possib

ility of a self-induced illness must be considered. Factitious illness occurs mo

re frequently than is probably recognized, since it falls outside the usual expe

ctations concerning causation of disease. Nonetheless, such a condition is a tru

e illness, although the pathogenesis must be redefined as emotional rather than

physical. Factitious diarrhea is a characteristic example of such an illness.

The clinical manifestations and diagnosis of factitious diarrhea will be reviewe

d here. This topic review will also consider factitious illnesses in general, wi

th emphasis on the most severe form of this disorder, Munchausen syndrome.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF FACTITIOUS DIARRHEA Factitious diarrhea may be charac

terized by a true increase in stool volume, which is self-induced, or the creati

on of an apparent increase in stool volume by the addition of various substances

to the stool. Surreptitious laxative abuse is the most frequent cause of factit

ious diarrhea, and often presents as chronic watery diarrhea of unknown etiology

. As many as 15 percent of patients referred to tertiary care centers for evalua

tion of chronic diarrhea were found to have laxative abuse as the cause of their

diarrhea [1]. Prior to making this diagnosis, an evaluation to rule out common

organic causes of diarrhea should be performed. (See "Approach to the adult with

chronic diarrhea in developed countries".) It is important to emphasize that no

t all patients with factitious diarrhea abuse laxatives since some individuals m

ay be unaware of the relationship between laxatives and diarrhea or that medicat

ions used for other conditions contain substances that can cause diarrhea.

Patient characteristics More than 90 percent of patients with factitious diarrhea

are women, many of whom are from higher socioeconomic classes, are often intell

igent and educated, and may be employed in a medical field. These patients often

seek care from many physicians, and have multiple hospital admissions in an eff

ort to establish the cause of the diarrhea. They also have a higher incidence of

anorexia nervosa, suggesting a common underlying psychiatric abnormality [2].

Clinical manifestations

Laxative abuse often presents as watery diarrhea that is high in frequency and v

olume [3,4]. Patients report between 10 and 20 bowel movements a day, with 24-ho

ur stool volumes ranging from 300 to 3000 mL. More than 50 percent of patients c

omplain of nocturnal bowel movements, which are not characteristic of functional

diarrhea, such as irritable bowel syndrome. Some patients also have blood in th

e stool, making the true diagnosis even more difficult to determine.

The diarrhea is often associated with crampy abdominal pain. This is a direct ef

fect of many laxatives, which increase the fluid content of the stool and enhanc

e gastrointestinal motility.

Weight loss is common, and can be severe enough to result in cachexia. Multiple

factors may contribute to weight loss other than the diarrhea. These include con

current nausea or vomiting (which may be seen with laxative abuse alone or in pa

tients with anorexia and bulimia who use laxatives in an effort to lose weight)

and diminished nutrient absorption. Some laxatives have a direct inhibitory effe

ct on nutrient absorption. As an example, rhein (an anthraquinone) and bisacodyl

(a diphenolic laxative) impair glucose absorption. These compounds may also cau

se mild steatorrhea and gastrointestinal protein loss.

Lethargy and generalized weakness, in addition to muscle weakness, are prominent

symptoms of laxative abuse. Malnutrition, dehydration, and hypokalemia may resu

lt.

Laxative abuse may also be associated with a number of fluid and electrolyte dis

orders:

Volume depletion, which can lead to orthostatic hypotension due to sodium and wa

ter loss in the stool.

Hypokalemia is frequently present due primarily to losses in the diarrheal fluid

. Hypovolemia-induced secondary hyperaldosteronism may also contribute by increa

sing colonic potassium secretion. Interestingly, urinary potassium excretion is

not increased by secondary hyperaldosteronism since the stimulatory effect of al

dosterone is offset by the decrease in sodium delivery to the potassium secretor

y site in the collecting tubule.

Diarrhea, particularly severe acute diarrhea, is classically associated with met

abolic acidosis due to the rapid loss of large amounts of bicarbonate [5,6]. How

ever, the chronic diarrhea caused by laxative abuse often results in metabolic a

lkalosis [3-5]. The alkalosis may be due in part to hypokalemia impairing the in

testinal reabsorption of chloride, thereby diminishing bicarbonate secretion int

o the intestinal lumen via chloride-bicarbonate exchange. Loss of a high-chlorid

e, low-bicarbonate solution can raise the plasma bicarbonate concentration, and

both volume depletion and hypokalemia prevent excretion of the excess bicarbonat

e in the urine. (See "Pathogenesis of metabolic alkalosis".)

Moderate to severe hypermagnesemia can occur if a magnesium-containing cathartic

is used, particularly in those patients where urinary magnesium excretion is im

paired because of volume depletion [7,8].

EVALUATION FOR FACTITIOUS DIARRHEA In addition to the history, evaluation of the

patient with suspected factitious diarrhea consists of stool analysis, attempted

detection of chemical laxatives, and endoscopic and/or radiologic examination [

9]. An adequate evaluation for suspected laxative abuse can usually be performed

on an outpatient basis. After organic causes of chronic diarrhea are ruled out,

the following flow chart may be used to evaluate the cause of factitious diarrh

ea (algorithm 1). (See "Approach to the adult with chronic diarrhea in developed

countries".)

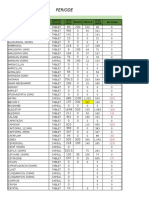

Stool analysis Stool analysis consists of measurement of stool osmolality, and so

dium, potassium, and magnesium concentrations [9]. An osmolal gap (calculator 1)

indicates the presence of an unmeasured solute which can be due to laxatives co

ntaining magnesium, sorbitol, lactose, lactulose, or polyethylene glycol as the

active ingredients. The osmotic gap in these settings usually exceeds 50 mosmol/

kg compared to a gap that is generally less than 50 mosmol/kg in secretory diarr

heas. The other disorders that can cause a secretory diarrhea are shown in the T

able (table 1).

The osmolar gap is calculated by subtracting twice the measured concentrations o

f sodium and potassium from 290-300 mosmol/kg which is the expected osmolality o

f freshly passed diarrheal stool.

Measurement of stool magnesium may be helpful if there is a substantial osmotic

gap [7]. A value above 108 mg/dL (45 mmol/L or 90 mEq/L) suggests magnesium-indu

ced diarrhea. Screening of stool water or urine by thin layer chromatography (se

e below) will not detect magnesium-containing cathartics.

Measurement of stool osmolality can also detect factitious diarrhea resulting fr

om the addition of water to the stool [9-11]. This diagnosis should be suspected

if the measured stool osmolality is lower than that of plasma since the colon c

annot dilute stool to an osmolality which is less than that of plasma.

Stool osmolality significantly higher than plasma (particularly with a high sodi

um concentration) raises the possibility that urine has contaminated the stool.

This can be confirmed by demonstrating high concentrations of urea and creatinin

e in the stool water. The stool osmolality may also increase if the stool is not

examined quickly due to breakdown by bacteria of carbohydrates into smaller, os

motically active molecules [9].

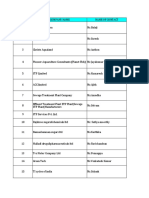

Detection of chemical laxatives Laxatives can be detected in the serum, stool, an

d urine. Serum concentrations are generally low, and reach maximal levels one to

two hours after ingestion. Urine concentrations may be up to 10 times higher th

an plasma concentrations; thus, testing the urine provides the best yield for la

xative detection (table 2). Many over-the-counter laxatives used to contain phen

olphthalein, which was reclassified because of carcinogenic effects in animals,

and is no longer available over-the-counter in the United States. Phenolphthalei

n could be identified using a test that can be performed at the bedside. Stool s

amples turn pink-red when alkalinized with NaOH [3]; another laxative, bisacodyl

, turns purple-blue in this setting [9]. Such assays should be abandoned because

they are not sufficiently sensitive; they should be replaced by spectrophotomet

ric or chromatographic assays [9].

Broad screening methods for both diphenolic laxatives and anthraquinones can be

done in most hospital laboratories with mass spectrometry or gas chromatography,

although the accuracy of these methods is incompletely understood [12]. Polyeth

ylene glycol containing laxatives should specifically be measured in the stool o

r urine because of the widespread use of these agents [13]. The sample may be se

nt in a small plastic container, and the use of serum separator tubes is not rec

ommended. To date, there have been no reported cases of factitious diarrhea asso

ciated with polyethylene glycol use. Many patients consume one or more of these

agents at a time, or may rotate agents, necessitating screening for all types of

laxatives. As noted above, these methods will not detect magnesium. Repeated an

alyses of stool and urine is wise, since patients may ingest laxatives intermitt

ently.

Endoscopic or radiologic examination Endoscopic or radiologic examination of the

colon may be helpful in some patients. Melanosis coli is a lesion that occurs on

ly with the use of anthraquinone-containing laxatives; it is not seen with osmot

ic or diphenolic agents. Melanosis coli can develop within four months of the on

set of laxative ingestion and can disappear in the same amount of time if laxati

ve use in discontinued. It appears as a dark brown discoloration of the colon wi

th lymph follicles shining through as pale patches (picture 1). These findings m

ay be evident in the rectum and sigmoid colon, although the entire colon may be

involved. If not evident on endoscopy, melanosis coli may be demonstrated histol

ogically by finding pigment in the macrophages of the lamina propria [14]. It mu

st be emphasized that melanosis coli is not specific to exposure to anthraquinon

e laxatives.

Cathartic colon is a rarely seen but severe manifestation of prolonged laxative

use. It is characterized by dilation of the large bowel, with decreased or absen

t haustrations noted on plain abdominal films or barium enema. The changes are u

sually most marked in the right colon, but can affect the entire colon.

Room search Searching the patient's room and possessions for laxatives or paraphe

rnalia used for deception is often a successful method used to support a diagnos

is of factitious diarrhea. Although it raises an ethical dilemma concerning inva

sion of the patient's privacy, it may be justified on grounds that a correct dia

gnosis will eliminate further diagnostic testing, and accelerate the initiation

of appropriate therapy.

Although often highly successful in confirming a suspected diagnosis of laxative

abuse, a room search should be considered as a diagnostic procedure which requi

res informed consent from the patient. There is no clear legal precedent which a

llows the physician to conduct a room search without the patient's consent and,

if a search is performed without consent, there is the possibility of civil liti

gation for invasion of privacy [15].

MUNCHAUSEN SYNDROME The syndrome of "factitious illness" includes a broad spectru

m of diagnoses that have a similar psychiatric etiology, yet a wide range of pre

sentations. It is to be emphasized that most patients with Munchausen syndrome d

o not present with factitious diarrhea and that not all causes of factitious dia

rrhea are examples of Munchausen syndrome.

In its milder forms, factitious illness can manifest merely as an exaggeration o

f physical symptoms in an effort to avoid responsibilities and gain sympathy (hy

pochondriasis).

More serious presentations involve feigning illness to obtain drugs or avoid pro

secution (malingering).

Munchausen syndrome is the most extreme form, and is characterized by the feigni

ng of severe illness to the point of undergoing multiple invasive procedures and

operations.

Whereas the malingerer has obvious motives of which he or she is fully aware, th

e patient with Munchausen syndrome has no ulterior motive other than to assume t

he role of a patient. Although the actions of such patients are deliberate and p

urposeful, they are used to pursue goals that are involuntarily adopted and esse

ntially hidden from the patient.

In contrast to patients with factitious diarrhea, malingerers are frequently per

ipatetic men of lower socioeconomic class who have a lifelong pattern of social

maladjustment, and who frequently are characterized as pathologic liars.

Characteristic features of Munchausen syndrome include the simulation of a sever

e or dramatic illness requiring hospitalization, disease often produced by self-

mutilation, multiple hospitalizations often at widely separated geographic locat

ions, pathological lying, aggressive and evasive behavior, and premature self-di

scharge from the hospital against medical advice when confronted by the medical

team.

These patients are medically sophisticated, often showing evidence of prior trea

tment including extensive hospital records and often multiple surgical scars. Th

eir behavior in the hospital is often disruptive, and they make frequent demands

for analgesic medications without signs or symptoms of withdrawal when they are

discontinued. Their symptoms shift from one organ system to another, and they t

olerate painful, invasive procedures without complaint [16].

The gastroenterologist is most likely to encounter patients with this syndrome w

hen they present with severe abdominal pain or other gastrointestinal complaints

. One case report, for example, described a young former nurse who presented wit

h severe abdominal pain and passage of blood and mucus rectally [17]. A barium e

nema showed severe inflammatory disease involving the rectum and sigmoid colon,

which eventually led to colectomy with creation of an ileostomy. Subsequently, t

he patient was found to have been self-instilling caustic soda into the rectum.

Munchausen syndrome by proxy (Polle syndrome) involves the induction of factitio

us illness in children by their parents. There are multiple reports on this sad

form of child abuse, several of which describe the induction of factitious diarr

hea in children by administration of laxatives [3]. (See "Munchausen syndrome by

proxy (medical child abuse)".)

Treatment The prognosis for patients with Munchausen syndrome is generally poor.

It is more favorable in those who exhibit a depressive-masochistic personality d

isorder, and least favorable in those with a predominantly antisocial personalit

y. Early psychiatric consultation should be requested, and if confrontation is t

o be undertaken at all, it should be done by the primary physician in a nonpunit

ive manner and without hostility. The most important aspect of management is ear

ly recognition of the disorder and avoidance of further invasive diagnostic or t

herapeutic interventions.

Ultimately, there is a change in the overall therapeutic goal from cure of the s

imulated disease to coping with the Munchausen syndrome. Some patients may be al

lowed to use the factitious illness as a means for maintaining contact with the

physician so that appropriate psychotherapy, behavior modification, and pharmaco

therapy aimed at treating the psychiatric disorder may be given.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Factitious diarrhea may be characterized by a true increase in stool volume, whi

ch is self-induced, or the creation of an apparent increase in stool volume by t

he addition of various substances to the stool. (See 'Introduction' above.)

Surreptitious laxative abuse is the most frequent cause of factitious diarrhea.

Laxative abuse often presents as watery diarrhea that is high in frequency and v

olume. The diarrhea is often associated with crampy abdominal pain. Lethargy and

generalized weakness, malnutrition, dehydration, and electrolyte abnormalities

may result. (See 'Clinical manifestations' above.)

In addition to the history, evaluation of the patient with suspected factitious

diarrhea consists of stool analysis and attempted detection of chemical laxative

s. Stool analysis consists of measurement of stool osmolality, and sodium, potas

sium, and magnesium concentrations. An osmolal gap (calculator 1) indicates the

presence of an unmeasured solute which can be due to laxatives containing magnes

ium, sorbitol, lactose, lactulose, or polyethylene glycol as the active ingredie

nts.

Colonoscopy may reveal melanosis coli and a cathartic colon may be seen on bariu

m enema. After organic causes of chronic diarrhea are ruled out, the following a

lgorithm may be used to evaluate the cause of factitious diarrhea (algorithm 1).

(See 'Evaluation for factitious diarrhea' above.)

Use of UpToDate is subject to the Subscription and License Agreement.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- HERING Law FalseDocument5 pagesHERING Law FalseVirag PatilNo ratings yet

- High Times - November 2023Document84 pagesHigh Times - November 2023miwoga7814No ratings yet

- Coma ManagementDocument5 pagesComa ManagementElena DocNo ratings yet

- Final Project MSWDocument57 pagesFinal Project MSWSaurabh KumarNo ratings yet

- 2019 SEATTLE CHILDREN'S Hospital. Healthcare-Professionals:clinical-Standard-Work-Asthma - PathwayDocument41 pages2019 SEATTLE CHILDREN'S Hospital. Healthcare-Professionals:clinical-Standard-Work-Asthma - PathwayVladimir Basurto100% (1)

- Excerpt From Treating Trauma-Related DissociationDocument14 pagesExcerpt From Treating Trauma-Related DissociationNortonMentalHealth100% (3)

- Enero: #Codigo Eess Resultado Prueba Fecha Fecha TamizajeDocument10 pagesEnero: #Codigo Eess Resultado Prueba Fecha Fecha TamizajeChristian JaraNo ratings yet

- Acute Respiratory Failure: Recognition and Early InterventionDocument31 pagesAcute Respiratory Failure: Recognition and Early InterventionChristian JaraNo ratings yet

- References: Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 22 (4), pp.547-553Document2 pagesReferences: Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 22 (4), pp.547-553Christian JaraNo ratings yet

- Tiki Taka CK InfectionsDocument6 pagesTiki Taka CK InfectionsChristian JaraNo ratings yet

- TiKa TaKa PediatricsDocument86 pagesTiKa TaKa PediatricsEmad MerganNo ratings yet

- Far MacoDocument28 pagesFar MacoChristian Jara100% (1)

- May Have - . - Might Have - . - Could Have - . .: Used To Give Explanations For Past EventsDocument19 pagesMay Have - . - Might Have - . - Could Have - . .: Used To Give Explanations For Past EventsChristian JaraNo ratings yet

- Neonatal PneumoniaDocument29 pagesNeonatal PneumoniaChristian JaraNo ratings yet

- Objective: Curriculum Vitae Md. Motaher Hossain Contact & DetailsDocument2 pagesObjective: Curriculum Vitae Md. Motaher Hossain Contact & DetailsNiaz AhmedNo ratings yet

- Summative Test Science Y5 SECTION ADocument10 pagesSummative Test Science Y5 SECTION AEiLeen TayNo ratings yet

- Format OpnameDocument21 pagesFormat OpnamerestutiyanaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Desistance From Crime Laub and SampsonDocument70 pagesUnderstanding Desistance From Crime Laub and Sampsonchrisgoss1No ratings yet

- Pe2 Lasw11w12Document4 pagesPe2 Lasw11w12christine mae picocNo ratings yet

- Analytical Customer UpdationDocument16 pagesAnalytical Customer UpdationSathish SmartNo ratings yet

- Activity 2: General Biology 2 (Quarter IV-Week 3)Document4 pagesActivity 2: General Biology 2 (Quarter IV-Week 3)KatsumiJ AkiNo ratings yet

- CSEC Biology June 2012 P2Document17 pagesCSEC Biology June 2012 P2Joy BoehmerNo ratings yet

- Lüscher Colour TestDocument1 pageLüscher Colour TestVicente Sebastián Márquez LecarosNo ratings yet

- Operation Management ReportDocument12 pagesOperation Management ReportMuntaha JunaidNo ratings yet

- QR CPG TobacoDisorderDocument8 pagesQR CPG TobacoDisorderiman14No ratings yet

- Sex Should Be Taught in Schools: Shafira Anindya Maharani X IPS 1 /29Document11 pagesSex Should Be Taught in Schools: Shafira Anindya Maharani X IPS 1 /29Shafira Anindya MaharaniNo ratings yet

- Selenia Ultra 45 EOL Letter v4Document1 pageSelenia Ultra 45 EOL Letter v4srinibmeNo ratings yet

- Gefico Maritime SectorDocument28 pagesGefico Maritime SectorAugustine Dharmaraj100% (1)

- Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: The History, Current View and New PerspectivesDocument14 pagesDiffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: The History, Current View and New PerspectivesPepe PintoNo ratings yet

- (Norma) Guia Fda CovidDocument14 pages(Norma) Guia Fda CovidJhovanaNo ratings yet

- Planning PlaygroundDocument16 pagesPlanning PlaygroundAdnan AliNo ratings yet

- Safe Operating Procedure Roller: General SafetyDocument4 pagesSafe Operating Procedure Roller: General SafetyRonald AranhaNo ratings yet

- CRANE SIGNAL PERSON TRAINING SlidesDocument73 pagesCRANE SIGNAL PERSON TRAINING SlidesAayush Agrawal100% (1)

- SUMMATIVE English8Document4 pagesSUMMATIVE English8Therese LlobreraNo ratings yet

- ErpDocument31 pagesErpNurul Badriah Anwar AliNo ratings yet

- Insomnia: Management of Underlying ProblemsDocument6 pagesInsomnia: Management of Underlying Problems7OrangesNo ratings yet

- Mosh RoomDocument21 pagesMosh RoomBrandon DishmanNo ratings yet

- Araldite - GT7074Document2 pagesAraldite - GT7074maz234No ratings yet