Professional Documents

Culture Documents

IA NYLJ Extent of Court Review 040308 16

Uploaded by

Irina CraciunOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

IA NYLJ Extent of Court Review 040308 16

Uploaded by

Irina CraciunCopyright:

Available Formats

INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION LAW

BY EMMANUEL GAILLARD

Ext ent of Court Revi ew of Publ i c Pol i cy

t is universally accepted that court

review of arbitral awards at the seat of

the arbitration or in the country where

recognition and enforcement is sought

includes an examination on the ground of

that particular jurisdictions conception of

international public policy. This principle

has been embodied, in particular, in

Article V(2)(b) of the New York

Convention on the Recognition and

Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards of

J une 10, 1958.

The content of international public

policy may, however, vary from one

jurisdiction to the other, both as regards

public policy requirements concerning the

merits of a dispute and as regards public

policy requirements concerning the arbitral

procedure (see E. Gaillard and J . Savage

(eds.), FOUCHARD GAILLARD

GOLDMAN, Kluwer, 1999, paragraphs

1645-1662 and 1710-1713). Each

jurisdictions understanding of international

public policy encompasses the set of

fundamental values a breach of which could

not be tolerated by that particular legal

order, even in international cases.

Economic Public Policy

The question of the content of

international public policy may arise in

some areas more acutely than in others, in

particular as regards economic public

_________________________________

Emmanuel Gaillard heads the

International Arbitration Group of

Shearman & Sterling. He is also a

Professor of law at University of Paris XII.

Yas Banifatemi, a partner in the firms

international arbitration group in Paris,

assisted in the preparation of this article.

Disclosure: The author represented Socit

SNF SAS SA in the proceedings between

SNF SAS SA and Cytec Industries before

the Paris Court of Appeals referred to in

this article.

policy. In European Union countries for

example, European antitrust law, as

embodied in particular in the provisions of

European Commission (EC) Treaty

Articles 81 and 82, is regarded as a matter

of public policy. EC Treaty policy. EC

Treaty Article 81 prohibits as

incompatible with the common market: all

agreements between undertakings,

decisions by associations of undertakings

and concerted practices which may affect

trade between Member States and which

have as their object or effect the

prevention, restriction or distortion of

competition within the common

market. EC Treaty Article 82 in turn

provides that [a]ny abuse by one or more

undertakings of a dominant position within

the common market or in a substantial part

of it shall be prohibited as incompatible

with the common market insofar as it may

affect trade between Member States.

As fundamental requirements of

European economic public policy, these

provisions must be applied by arbitral

tribunals, in order for the resulting award

to be fully enforceable in member states of

the European Union, in any dispute to

which the antitrust rules of the European

Union apply. This principle results in

particular from the Eco Swiss decision of

the European Court of Justice (ECJ ) (Eco

Swiss China Times Ltd. v. Benetton

International NV, J une 1, 1999, available

on the ECJ Web site):

35. it is in the interest of

efficient arbitration proceedings

that review of arbitration awards

should be limited in scope and that

annulment of or refusal to

recognise an award should be

possible only in exceptional

circumstances.

36. However,Article 81 EC (ex

Article 85) constitutes a

fundamental provision which is

essential for the accomplishment

of the tasks entrusted to the

Community and, in particular, for

the functioning of the internal

market. The importance of such a

provision led the framers of the

Treaty to provide expressly, in

Article 81(2) EC (ex

Article 85(2)), that any agreements

or decisions prohibited pursuant to

that article are to be automatically

void.

37. It follows that where its

domestic rules of procedure

require a national court to grant an

application for annulment of an

arbitration award where such an

application is founded on failure to

observe national rules of public

policy, it must also grant such an

application where it is founded on

failure to comply with the

prohibition laid down in

Article 81(1) EC (ex Article

85(1)).

38. That conclusion is not affected

by the fact that the New York

Convention of J une 10, 1958 on

the Recognition and Enforcement

of Foreign Arbitral Awards, which

has been ratified by all the

Member States provides that

recognition and enforcement of an

arbitration award may be refused

only on certain specific grounds

[reference to Article V(1)(c) and

(e)].

39. For the reasons stated in

paragraph 36 above, the provisions

of Article 81 EC (ex Article 85)

I

NEW YORK J OURNAL THURSDAY, APRIL 5, 2007

may be regarded as a matter of public

policy within the meaning of the New

York Convention.

The courts of a nonmember state may

refuse to recognize European antitrust law

as falling within their conception of

international public policy. Of particular

interest is, in this respect, the J udgment of

March 8, 2006 rendered by the Swiss

Federal Tribunal in the case of Tensacciai

SpA v. Freyssinet Terra Armata R.L. (see

English translation and commentary by

Charles Poncet, in WORLD

ARBITRATION & MEDIATION

REPORT, vol. 17, No. 7, J uly 2006, 221, at

227):

After reviewing once again the concept

of public policyand after examining

further the nature of European Competition

Lawthis Court holds that there is no more

room for doubt: the provisions of

competition laws, whatever they may be, do

not belong to the essential and broadly

recognized values which, according to the

concepts prevailing in Switzerland, would

have to be found in any legal order.

Consequently, the violation of such a

provision does not fall within the scope of

art. 190(2)(e) PILA. The possibility of such

a violation affecting one of the principles

that case law deducted from the concept of

material public policy is hereby

reserved.As European or Italian

competition laws do not belong to the realm

of public policy as stated in art. 190(2)(e)

PILA, this appeal can only be rejected

without further analysis of the way in which

that law was applied by the Arbitral

Tribunal.

Conversely, in European Union

countries, where European antitrust law is

regarded as a matter of economic public

policy, the question would arise as to the

extent to which the application of European

antitrust law by the arbitrators must be

controlled by the courts when determining

whether an award complies with

international public policy. This particular

question was tested recently in parallel

court proceedings in France and in Belgium

in the matter of the ICC arbitration SNF

SAS S.A. v. Cytec Indutries.

The SNF Awards

The French company SNF SAS SA

(SNF) had entered in 1993 into an

agreement with Dutch company Cytec

Industries BV (Cytec) for the purchase of

acrylamide monomer, a chemical

component used for water treating, paper,

mining, and oil field chemicals, coatings

and adhesives. The 1993 agreement

replaced a previous three-year agreement of

1991. In 2000, Cytec initiated arbitration

proceedings after SNF sought the

termination of the 1993 agreement based on

its breach of EC Treaty Articles 81 and 82.

The arbitration was subject to French law

and had its seat in Brussels (Belgium).

In a partial award on the principle of

liability dated Nov. 5, 2002, the Arbitral

Tribunal held that the 1993 agreement was

null and void ab initio because its object

and purpose was to prevent SNF from

accessing for eight years the European

market of acrylamide monomer and thus

constituted a restriction of competition

within the common market in breach of EC

Treaty Article 81. The tribunal further held

that Cytec had not abused a dominant

position within the meaning of EC Treaty

Article 82.

The tribunal also determined that the

parties had shared responsibility as both

SNF and Cytec should have known that

their agreement was null and void. In its

final award of J uly 28, 2004, the tribunal

granted damages exclusively to Cytec,

covering the unsold volumes of acrylamide

monomer on the basis of the 1991

agreement and the applicable higher

purchase price, as well as damages for the

period from J uly 1995 to J anuary 2000

under the 1993 agreement. Compound

interest at the rate of 7 percent was applied

on the entire amounts awarded to Cytec

until J une 30, 2004. SNFs compensation

requests were rejected in their entirety on

the basis that SNF had not established that

it could have obtained from Cytec more

favorable purchase conditions than those

under the 1993 agreement or that it could

have purchased acrylamide monomer at

better prices from other producers.

SNF challenged the two awards

separately before the French courts where

enforcement was sought and the Belgian

courts of the seat of the arbitration. Before

the Paris Court of Appeals, SNF appealed

on Oct. 6, 2004 against two enforcement

orders of Sept. 15, 2004 by the president of

the Paris Tribunal de grande instance

relating to the two awards of 2002 and

2004. Before the Brussels Tribunal de

premire instance, SNF applied on May 19,

2005 for the setting aside of the two

awards of 2002 and 2004. SNFs

applications in both instances were based,

among others, on the awards being

contrary to European antitrust law as a

matter of public policy, as embodied in the

provisions of EC Treaty Articles 81 and

82.

Whether control of public policy

should be restricted only to

manifest violations or should

concern any violations is a question

before the French Cour de

cassation.

Manifest Violations

In the French proceedings, SNFs

application was rejected and the Paris

Court of Appeals confirmed the

enforcement orders. The Court held in

essence that:

Considering that although it is

correct, as reminded by company SNF-

SAS, that under Article 1502 of the

New Code of Civil Procedure, the Court

of Appeals exercises its power of

review on the basis of the enumerated

grounds by seeking in law and in fact,

and without limitation, all factors

establishing a breach, the Court, which

is not sitting in judgment of the trial but

of the award, exercises only an extrinsic

control as regards the breach of

international public policy as only the

recognition or the enforcement of the

award is examined in light of its

conformity with international public

policy at the time it is presented to the

judge.

The court held that the tribunal had

complied with international public

policy in applying European antitrust

law and declaring the 1993 agreement

null and void on the basis of EC Treaty

Article 81 and rejecting SNFs

allegation relating to Cytecs abuse of

dominant position. The court further

held that the assessment of the elements

of fact and law in light of Articles 81

and 82 came within the tribunals power

and that it could not substitute its own

assessment for that of the tribunal

without engaging into a review of the

merits, and that the consequences in

terms of damages did not fall within the

courts control under Article 1502, 5,

of the New Code of Civil Procedure.

The court, however, recognized that

SNF was challenging the result of the

awards rather than the tribunals ability

to understand and apply European

antitrust laws. It is, indeed, not the

abstract rule of law applied by the

arbitrators which must be measured

against the requirements of international

public policy, but the actual result

reached by the arbitrators, as

established by the Paris Court of

Appeals decision in the Reynolds case

(Paris Court of Appeals, Lebanese

Traders Distributors & Consultants

LTDC v. Reynolds, Oct. 27, 1994, 10

INT.L ARB. REP. E7 (February 1995);

see also FOUCHARD GAILLARD

NEW YORK J OURNAL THURSDAY, APRIL 5, 2007

GOLDMAN, cited above, paragraph 1649):

the scrutiny of the Courtmust

bear not upon the evaluation made by

the arbitrators with regard to the cited

requirements of public policy, but on

the solution given to the dispute,

annulment only being incurred if

enforcement of that solution violates

the aforementioned public policy.

The Paris Court of Appeals reluctance

to go beyond an extrinsic control of

public policy in order to avoid engaging in

a review of the merits dates back to its well-

known decision in the Euromissile case of

2004 (Paris Court of Appeals, SA Thales

Air Dfense v. Euromissile, Nov. 18, 2004,

French version in 2005 REVUE DE

LARBITRAGE 751). In an award of

Oct. 23, 2002, the tribunal in that case held

Thales liable for unlawful breach of

contract under its contractual arrangements

with Euromissile, but did not declare such

arrangements null and void pursuant to EC

Treaty Article 81. Considering that the

effect given by the tribunal to such

arrangements was contrary to the

prohibition of restrictions of competition

laid down in Article 81, Thales sought the

annulment of the award on the basis that the

awards recognition or enforcement would

be contrary to international public policy

under Article 1502, 5, of the New Code of

Civil Procedure.

The Paris Court of Appeals noted in

Euromissile that the parties had never

raised the issue of the conformity of their

contractual arrangements with EC Treaty

Article 81 before the Arbitral Tribunal but

that Thales could nevertheless challenge the

conformity of its contractual arrangements

with European antitrust law to the extent

that the enforcement of the award would

result in a violation of Article 81. At the

same time, the court laid emphasis on its

control being confined to situations where

the recognition or enforcement of awards

would breach the French legal order in an

unacceptable manner, such breach

constituting a manifest violation of an

essential rule or a fundamental principle

such as Article 81.

The court held, however, that it was not

in a position to assess the parties

arguments in light of European antitrust law

without a legal and economic analysis and

that, in the context of annulment

proceedings, it could not conclude whether

the arrangements between Thales and

Euromissile constituted a restriction of

competition within the common market in

breach of Article 81.

The court concluded that the violation

of international public policy within the

meaning of Article 1502, 5, of the New

Code of Civil Procedure must be manifest,

actual and specific [flagrante, effective et

concrte], and that, although it could,

within its powers, make a determination in

fact and in law, it could not determine the

merits of a complex dispute regarding the

possible illegality of contractual

arrangements that had never been argued

by the parties and never assessed by the

arbitrators (for a similar reasoning by

Italian courts as regards European antitrust

law, see Florence Court of Appeals, X.

S.A.. v. Y., March 21, 2006, summarized in

French GAZETTE DU PALAIS, Oct. 15-

17, 2006, at 57).

The expression used by the Paris Court

of Appeals in Euromissile seems to have

been introduced by the French Cour de

cassation in an unpublished decision of

March 21, 2000, holding that the violation

of international public policy within the

meaning of Article 1502, 5, of the New

Code of Civil Procedure, assessed at the

time when the recognition and the

enforcement of the award is sought, must

be manifest, actual and specific [flagrante,

effective et concrte].

This reasoning has been approved by a

number of authors (see, in particular, the

commentaries of the Thales v. Euromissile

decision by L. G. Radicati di Brozolo,

Lillicit qui crve les yeux: critre de

contrle des sentences au regard de lordre

public international ( propos de larrt

Thals de la Cour dappel de Paris), 2005

REVUE DE LARBITRAGE 529; T. Clay,

2005 DALLOZ Pan. 3050; A. Mourre, 132

J OURNAL DU DROIT

INTERNATIONAL 357 (2005)) and

criticized by others (see also commentaries

of the Thales v. Euromissile decision by E.

Loquin, 2005 REVUE TRIMESTRIELLE

DE DROIT COMMERCIAL 263; C.

Seraglini, Laffaire Thals et le non-usage

immodr de lexception dordre public

(ou les drglements de la

drglementation), 2005 GAZ. PAL.-LES

CAHIERS DE LARBITRAGE 5 (No. 2);

S. Bolle, 2006 REVUE CRITIQUE DE

DROIT INTERNATIONAL PRIVE 111).

Control, Manifest Violations

By contrast, in the Belgian proceedings,

the Brussels Tribunal de grande instance

clearly distanced its approach from that of

the Paris Court of Appeals and held that

any violation of international public policy

must be sanctioned under the applicable

provisions of Belgian law (Article 1704,

2, of the Judicial Code), and not only

manifest, actual and specific violations

within the meaning of the Euromissile

decision of the Paris Court of Appeals:

Pursuant to Article 1704, 2, any

violation of public policy must be

sanctioned by the annulment of the

award and not only violations that are

manifest, actual and specific

[flagrantes, effectives et concrtes]

(terms of the Thales Decision,

Paris, Nov. 18, 2004 [references].

Applying this approach, the Brussels

Tribunal decided that the Tribunal had

rightly decided that in the circumstances

of the case an abuse of dominant

position by Cytec had not been

established pursuant to EC Treaty

Article 82. However, as regards the

conformity of the awards with EC

Treaty Article 81 and SNFs argument

that the enforcement of the awards

resulted in implementing illicit

agreements at higher prices than if the

agreements had not been declared null

and void, the Brussels Tribunal decided

to set aside the awards in their entirety

on the basis that the Arbitral Tribunals

reasoning was contradictory in essence.

Indeed, the Brussels Tribunal

determined that the Arbitral Tribunal

could not decide, on the one hand, that

the 1993 agreement constituted a

restriction of competition because it was

intended to prevent SNF from entering

the common market as a producer of

acrylamide monomer and was thus null

and void ab initio pursuant to Article 81

and, on the other hand, that in free

market conditions SNF would have

nevertheless continued to purchase

acrylamide monomer from Cytec for the

same period, at higher prices and

without being in a position to enter the

production market of acrylamide

monomer. The Brussels Tribunal

concluded that such contradiction

undermined the effectiveness of

European antitrust law because, as a

result of the annulment of the 1993

agreement, Cytec ended up obtaining in

damages higher amounts than those it

would have obtained if the agreement

had continued to be implemented while

SNF, who had sought the annulment of

an agreement contrary to public policy,

ended up in a worse situation than it

would have been in had it continued the

implementation of the 1993 agreement.

Importantly, the Brussels Tribunal

found that the anticompetitive nature of

the 1993 agreement was not related to

the fact that the agreed prices were

below market prices, but resulted from

the fact that it prevented, for a long

time, SNF from entering the production

market of acrylamide monomer. The

annulment of the awards is based on the

Brussels Tribunals determination that

the awards were contrary to EC Treaty

Article 81 to the extent that, through

their solution to the dispute, they

result[ed] in giving effect to an

agreement that was determined to be

anti-competitive (emphasis added).

NEW YORK J OURNAL THURSDAY, APRIL 5, 2007

The tribunal thus measured the actual result

reached by the arbitrators against the

requirements of public policy embodied in

European antitrust law.

The disparity between the two lines of

reasoning in light of European antitrust law

as a matter of public policy-annulment by

the Brussels Tribunal of the awards based

on the violation, by the solution reached, of

Article 81, as compared to the refusal by

the Paris Court to enter into what it

considered to be a review of the meritsis

all the more remarkable in that the two

courts were seized of exactly the same facts

and the same legal arguments. The Paris

Courts reluctance can be justified even less

when one considers the courts own

jurisprudence establishing an in concreto

control of public policy in light of the

solution given to the dispute by the

arbitrators (Reynolds case cited above).

Under the manifest violation test, on the

other hand, the very notion of public policy

would be undermined as a violation of

economic public policy would almost never

be manifest.

Conclusion

The question of whether the control of

public policy should be restricted only to

manifest violations or whether it should

concern any violations is now a question

before the French Cour de cassation, SNF

having appealed from the Paris Court of

Appeals decision to the French supreme

court. Considering that court control of

compliance with international public policy

is already carried out very sparingly, it is

hoped that the Cour de cassation will decide

that there is no room for a further

attenuation of public policy, in particular of

economic public policy, by restricting the

courts review to only manifest

violations.

_________________________________

Reprinted with permission from the April 5, 2007

edition of the New York Law J ournal 2007 ALM

Properties, Inc. All rights reserved. Further duplication

without permission is prohibited. For information,

contact 212-545-6111 or visit www.almreprints.com.

#070-09-07-0006

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Sample Opposition To Motion To Strike Portions of Complaint in United States District CourtDocument2 pagesSample Opposition To Motion To Strike Portions of Complaint in United States District CourtStan Burman100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- How To Create A Powerful Brand Identity (A Step-by-Step Guide) PDFDocument35 pagesHow To Create A Powerful Brand Identity (A Step-by-Step Guide) PDFCaroline NobreNo ratings yet

- 1934 PARIS AIRSHOW REPORT - Part1 PDFDocument11 pages1934 PARIS AIRSHOW REPORT - Part1 PDFstarsalingsoul8000No ratings yet

- SPH4U Assignment - The Wave Nature of LightDocument2 pagesSPH4U Assignment - The Wave Nature of LightMatthew GreesonNo ratings yet

- Hotel ManagementDocument34 pagesHotel ManagementGurlagan Sher GillNo ratings yet

- Guide To Growing MangoDocument8 pagesGuide To Growing MangoRhenn Las100% (2)

- FIRE FIGHTING ROBOT (Mini Project)Document21 pagesFIRE FIGHTING ROBOT (Mini Project)Hisham Kunjumuhammed100% (2)

- G.R. No. 185449, November 12, 2014 Del Castillo Digest By: DOLARDocument2 pagesG.R. No. 185449, November 12, 2014 Del Castillo Digest By: DOLARTheodore DolarNo ratings yet

- BS 8541-1-2012Document70 pagesBS 8541-1-2012Johnny MongesNo ratings yet

- 312 Nyac I in One DocumentDocument492 pages312 Nyac I in One DocumentIrina CraciunNo ratings yet

- 1835 Lesser Wallach 12 Deadly SinsDocument11 pages1835 Lesser Wallach 12 Deadly SinsIrina CraciunNo ratings yet

- Applicable Laws ProceduresDocument11 pagesApplicable Laws ProceduresIrina CraciunNo ratings yet

- Foundations of DemocracyDocument102 pagesFoundations of DemocracyIrina CraciunNo ratings yet

- Doterra Enrollment Kits 2016 NewDocument3 pagesDoterra Enrollment Kits 2016 Newapi-261515449No ratings yet

- Missouri Courts Appellate PracticeDocument27 pagesMissouri Courts Appellate PracticeGeneNo ratings yet

- Aircraftdesigngroup PDFDocument1 pageAircraftdesigngroup PDFsugiNo ratings yet

- Building Program Template AY02Document14 pagesBuilding Program Template AY02Amy JaneNo ratings yet

- Amare Yalew: Work Authorization: Green Card HolderDocument3 pagesAmare Yalew: Work Authorization: Green Card HolderrecruiterkkNo ratings yet

- 90FF1DC58987 PDFDocument9 pages90FF1DC58987 PDFfanta tasfayeNo ratings yet

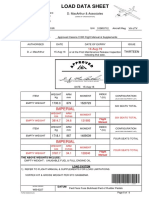

- Load Data Sheet: ImperialDocument3 pagesLoad Data Sheet: ImperialLaurean Cub BlankNo ratings yet

- Forecasting of Nonlinear Time Series Using Artificial Neural NetworkDocument9 pagesForecasting of Nonlinear Time Series Using Artificial Neural NetworkranaNo ratings yet

- Accomplishment ReportDocument1 pageAccomplishment ReportMaria MiguelNo ratings yet

- A Novel Adoption of LSTM in Customer Touchpoint Prediction Problems Presentation 1Document73 pagesA Novel Adoption of LSTM in Customer Touchpoint Prediction Problems Presentation 1Os MNo ratings yet

- BSCSE at UIUDocument110 pagesBSCSE at UIUshamir mahmudNo ratings yet

- Cam Action: Series: Inch StandardDocument6 pagesCam Action: Series: Inch StandardVishwa NNo ratings yet

- Draft Contract Agreement 08032018Document6 pagesDraft Contract Agreement 08032018Xylo SolisNo ratings yet

- Extent of The Use of Instructional Materials in The Effective Teaching and Learning of Home Home EconomicsDocument47 pagesExtent of The Use of Instructional Materials in The Effective Teaching and Learning of Home Home Economicschukwu solomon75% (4)

- Brochure Ref 670Document4 pagesBrochure Ref 670veerabossNo ratings yet

- Ytrig Tuchchh TVDocument10 pagesYtrig Tuchchh TVYogesh ChhaprooNo ratings yet

- Binary File MCQ Question Bank For Class 12 - CBSE PythonDocument51 pagesBinary File MCQ Question Bank For Class 12 - CBSE Python09whitedevil90No ratings yet

- Hayashi Q Econometica 82Document16 pagesHayashi Q Econometica 82Franco VenesiaNo ratings yet

- Business Environment Analysis - Saudi ArabiaDocument24 pagesBusiness Environment Analysis - Saudi ArabiaAmlan JenaNo ratings yet

- Functions of Commercial Banks: Primary and Secondary FunctionsDocument3 pagesFunctions of Commercial Banks: Primary and Secondary FunctionsPavan Kumar SuralaNo ratings yet

- Simoreg ErrorDocument30 pagesSimoreg Errorphth411No ratings yet