Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Listening Review

Uploaded by

ungulata0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views5 pagesMaterial is obviously pixelated and the colours are what we might expect. There is a fuzziness to many of the images that stands in direct contrast to the sharpness and precision of Xenakis's ideas. The book is littered with typographical errors and mistakes, of which only some of the most excruciating.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentMaterial is obviously pixelated and the colours are what we might expect. There is a fuzziness to many of the images that stands in direct contrast to the sharpness and precision of Xenakis's ideas. The book is littered with typographical errors and mistakes, of which only some of the most excruciating.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views5 pagesListening Review

Uploaded by

ungulataMaterial is obviously pixelated and the colours are what we might expect. There is a fuzziness to many of the images that stands in direct contrast to the sharpness and precision of Xenakis's ideas. The book is littered with typographical errors and mistakes, of which only some of the most excruciating.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

material is obviously pixelated, and the colours

are what we might expect when we print our

holiday snaps on cheap copy paper using an

ink-jet printer. There is a fuzziness to many of

the images that stands in direct contrast to the

sharpness and precision of Xenakiss ideas.

Moreover, the size of the reproduced sketches

sometimes makes the written notes on them

partially indecipherable: they still function as il-

lustrations, but may prove frustrating for

readers with more than a musical amateurs

interest in the architectural and engineering

issues involved.

The poor standard of production is not just

limited to the illustrations. The book is littered

with typographical errors and mistakes, of

which the following are only some of the most

excruciating. In the list of abbreviations at the

books beginning, Le Corbusier is written as

Le Cobusier. On page 8, in one and the same

column, the piece Xenakis created for the

Pavilion is listed once as Concert PH (wrong)

and once as Concret PH (right). At one point,

avant-garde is written as as avant-guard while

at another the otherwise correctly titled

Gravesaner Blatter become the Gravesano Blatter

(p. 165). On page 76, at the bottom of a

column, the end of a sentence has simply dis-

appeared. Footnotes and footnote cues are

another source of frustration: page 152 has two

footnotes numbered 15, one of which is

referenced in the text as 16; on the next page,

the footnotes in the footer itself are listed as 7,

18, 9 instead of 17, 18, 19 like the corresponding

footnote cues in the main text. Finally, in Sven

Sterkens appendix, which even by the stand-

ards of the rest of the volume has an appalling

number of typing errors, Xenakiss own name

is at one point chopped down to nakis, while

on page 313, in a single and rather short

column, his daughters name is spelt variously

as Ma khi and Ma hki.

Presumably, costs were a major consideration

in the production of this volume and in one

way we should probably be grateful that this

important material has been made available at

what is a relatively low price. But at what cost

the low price? Expense has been the death

knell of many an architectural vision, including

several projects by Xenakis discussed in this

book. And though it is traditionally music that

is portrayed as a fleeting, temporal art, we can

still listen to the music Vare' se and Xenakis

created for the Philips Pavilion, but the

Pavilion itself is gone. Few of us will ever be

able to get a real sense of the space, scale, and

impact in their local settings of Xenakiss archi-

tectural works, not to mention his Polytopes.

Thus, this reviewer can only conclude with a

plea for a new, deluxe edition, with larger and

legible illustrations on photo-quality paper, a

professionally proofread text, clearer organiza-

tionin short, an edition that really would

provide a lasting and inspiring testimony to

Xenakiss dual musical and architectural

genius.

M. J. GRANT

Georg-August-Universitat Gottingen

doi:10.1093/ml/gcq046

Listening. By Jean-Luc Nancy. Trans. by Char-

lotte Mandell. pp. xiv 85. (Fordham Uni-

versity Press, New York, 2007, $16. ISBN

978-0-8232-2773-0.)

Listening is a short but significant contribution

to the Continental philosophy of music by one

of Frances leading thinkers. Dense and poetic,

its prose is grounded in the rich post-

phenomenological tradition, and this volume

sets itself a challenging twofold task: to reunite

sensation and understanding in the figure of lis-

tening, and to restore timbre (as resonance)

back to its pride of place within the musical

event.

The title essay, Listening, begins with the

question of philosophys limitations: whether it

can approach listening in an appropriate

manner: Is listening something of which phil-

osophy is capable? Or . . . hasnt philosophy

superimposed upon listening, beforehand and

of necessity, or else substituted for listening,

something else that might be more on the order

of understanding? (p. 1). Given that Between

sight and hearing there is no reciprocity

(p. 10), Nancy develops an argument comparing

the simultaneity of the visible and the contempor-

aneity of the audible (p. 16): the fact that

sonorous presence is an essentially mobile at

the same time (p. 16), and that in the case of

the ear, is there withdrawal and turning

inward, a making resonant, but, in the case of

the eye, there is manifestation and display, a

making evident (p. 3). The following extrapola-

tion is key: the visual is tendentially mimetic,

and the sonorous tendentially methexic (that

is, having to do with participation, sharing, or

contagion), which does not mean that these

tendencies do not interact (p. 10). Contagion

is an important mechanism for resonance, for

it allows Nancy to enter the following phenom-

enology of sonority: The sonorous, on the

other hand, outweighs form. It does not

467

dissolve it, but rather enlarges it; it gives it an

amplitude, a density, and a vibration or undula-

tion whose outline never does anything but

approach. The visual persists until its disap-

pearance; the sonorous appears and fades away

into its permanence (p. 2).

Considering the opposition of sense and

truth, Nancy asks, shouldnt truth itself . . . be

listened to rather than seen? (p. 4). Pursuing

the notion that truth is emergent as sonority,

Nancy frames his trajectory with a note on the

type of philosophical attitude he is trying to

open up: Here we want to prick up the philosophic-

al ear (p. 3), and this is because To listen is

tendre loreilleliterally, to stretch the earan

expression that evokes a singular mobility,

among the sensory apparatuses, of the pinna of

the earit is an intensification and a concern,

a curiosity or an anxiety (p. 5). Nancy

expands this point with reference to the etymol-

ogy of ecouter back through its roots in auris and

auscultare. The point of lending, stretching, and

straining the ear is less what presents itself to

viewform, idea, painting, representation,

aspect, phenomenon, composition, and more

what arises instead in accent, tone, timbre, res-

onance, and sound (p. 3). A superficial, and

largely correct, reading of this point notes that

this is a turn from structure to meaning, from

what sonorous presence expresses to what it

affords. It is also something more: a significant

turn away from transcendental phenomenology

towards a qualitatively different mode of

thought. Indeed, whether it is a mode of

thought that is sought in the turn from repre-

sentation and phenomenon is itself part of the

question.

Having asked if truth should be listened to,

Nancy asks a related, ontological question:

What does it mean for a being to be immersed

entirely in listening, formed by listening, or in

listening, listening with all his being? (p. 4);

What does it mean to exist according to listen-

ing, for it and through it? (p. 5). At this point,

Nancy begins to articulate his own contribution:

the sound that is musically listened to, that is

gathered and scrutinized for itself, not,

however as an acoustic phenomenon (or not

merely as one) but as a resonant meaning, a

meaning whose sense is supposed to be found in

resonance, and only in resonance (p. 7).

Taking up the notion of straining towards the

listening object, he develops a phenomenology

of listening intention (noting caveats about the

very concept of intention) with implications for

the direction of the subject and its constitution

as, and in relation to, listening: To be listening

is always to be on the edge of meaning, or in

an edgy meaning of extremity, and as if the

sound were precisely nothing else than this

edge, this fringe, this margin (p. 7). Ultimately,

according to Nancy, it must be argued that

A self is nothing other than a form or function

of referral: a self is made of a relation to self, or

of a presence to self (p. 8). In this sense, it is

worth noting the grammar of the frequent

phrase To be listening is to be x, by which

being is phrased in terms of its ontological con-

stitution as listening: to be listening as in to be

old or to be a musician alongside the more

obvious to be currently engaged in the activity

of listening. The lesson is that listening is a

question of being: listening . . . can and must

appear to us not as a metaphor for access to

self, but as the reality of this access, a reality

consequently indissociably mine and other,

singular and plural, as much as it is

material and spiritual and signifying and

a-signifying (p. 12).

Nancy describes the kind of self towards

which listening strains: When one is listening,

one is on the lookout for a subject, something

(itself) that identifies itself by resonating from

self to self, in itself and for itself, hence outside

of itself, at once the same as and other than

itself (p. 9). He comes close to articulating

a proto-sociology of musical subjectivity,

articulating it as a kind of pathologyisnt

sense first of all, every time, a crisis of self ?

(p. 9)in which the singularity of sonorous

presence (p. 10, et passim) is both what drives

the subject towards itself (referral) and divides

or separates it from itself (resonance). Indeed,

for Nancy, the significance of this is that it

shows how listening is paradigmatic of the

subject and an essential constituent of subjectiv-

ity: Listening thus forms the perceptible singu-

larity that bears in the most ostensive way the

perceptible or sensitive (aisthetic) condition as

such: the sharing of an inside/outside, division

and participation, de-connection and conta-

gion (p. 14). The point is also not just that lis-

tening is a matter of ethics, but that it is an

ontological issue concerning the sense of the

world. Indeed, the issue lies above and beyond

secondary debates about the role of Music

(which is, after all, only one way of

appropriating and channelling listening) in

such secondary matters as self-expression and

social identity.

The reality of this access is a matter of

sonorous time, and sonorous time takes place

immediately according to a completely differ-

ent dimension, which is not that of simple suc-

468

cession (corollary of the negative instant). It is a

present in waves on a swell, not in a point on a

line; it is a time that opens up, that is hollowed

out, that is enlarged or ramified, that envelops

or separates, that becomes or is turned into a

loop, that stretches out or contracts, and so on

(p. 13). There is a question here about whether

the surprise of sonorous presence presents a

problem for the subject. As resonance is set in

motion, and the subject summoned into some

form of proto-being, how does the subject cope

with the rhythmic rise and fall of resonance?

Rhythm, Nancy writes, is nothing other than

the time of time, the vibration of time itself in

the stroke of a present that presents itself by

separating it from itself, freeing it from its

simple stanza to make it into scansion (rise,

raising of the foot that beats) and cadence (fall,

passage into the pause). Thus, rhythm separates

the succession of the linearity of the sequence

or length of time: it bends time to give it to

time itself, and it is in this way that it folds and

unfolds a self (p. 17). Temporality, moreover,

defines the subject as what separates itself, not

only from the other or from the pure there,

but also from self (p. 17). Nancy is ambivalent

as to whether or not this separation, this

rhythmic division of the self from itself, is plea-

surable, painful, traumatic, or a crisis (p. 9),

especially given his comment elsewhere that

the intimacy of music is an intimacy more

intimate than any evocation or any invocation

(p. 59) and his insistence throughout Listening

that resonance is a matter, not of listening style

(over which the subject may exercise choice),

but of fundamental ontology (through which

the subject is chosen). The question is twofold:

first, whether an underlying or primal event of

separation with that kind of tone motivates lis-

tening (listening for fear of losing the self,

perhaps); and second, whether attending and

concentrating the mind (i.e. one side of listen-

ing) is not only a necessary response to

sonorous presence and a mode of emergent

activity, but itself a creative act of making

sense both of and in the worldchanging,

bending, manipulating, and transforming time,

and thus difficult and sometimes stressful.

Nancy draws together arguments about the

arrival of sonorous presence and about the

self-separation of the subject in order to draw

a line under standard phenomenological

accounts of the subject and temporality (pp.

18^22, 28^30), and to draw out both the transi-

tive sense of etre and a non-intentional concep-

tion of subjectivity. He proposes that music (or

even sound in general) is not exactly a phenom-

enon; that is to say, it does not stem from a

logic of manifestation. It stems from a different

logic, which would have to be called evocation,

but in this precise sense: while manifestation

brings presence to light, evocation summons

(convokes, invokes) presence to itself (p. 20).

This has important implications for the

question of the subject and subjectivity. It is a

question, then, of going back from the phenom-

enological subject, an intentional line of sight,

to a resonant subject. . . .The subject of the lis-

tening or the subject who is listening . . . is not

a phenomenological subject (p. 21), and is

subject less to a criterion of cognitive consis-

tency than to a certain poetic consistency that

affords the aesthetic the opportunity to deter-

mine the specific details of the resonance, its

precise timbre and affective quality. Alongside

intention, sound is what places its subject,

which has not preceded it with an aim, in

tension, or under tension (p. 20); indeed, there

is only a subject . . .that resounds, responding

to a momentum, a summons, a convocation of

sense (p. 30).

For Nancy, musical listening is like the per-

mission, the elaboration, and the intensification

of the keenest disposition of the auditory

sense (pp. 26^7); it is the paradigmatic usage

of the ears. Meaning, sense, and direction

begin, not with intention, but with listening,

with the resounding return of resonance;

indeed, Sense reaches me long before it leaves

me, even though it reaches me only by leaving

in the same moment (p. 30; cf. p. 20).

At this point, Nancy introduces the concept of

timbre, which he places at the centre of listen-

ing: the first consistency of sonorous sense as

such (p. 40). By first Nancy means that

Rather than speaking of timbre and listening

in terms of intentional aim, it is necessary to

say that before any relationship to object, listen-

ing opens up in timbre (p. 40); he also could

be taken to mean that the first event of and in

listening (the passing of aspect perception) is

timbral in nature. According to Nancy, reso-

nance is at once listening to timbre and the

timbre of listening (p. 40); Timbre is the reso-

nance of sound: or sound itself (p. 40). By this

he means that timbre becomes a sharing that

becomes subject (p. 41), and is thus the begin-

nings of the echo of the subject (p. 39). While,

as he says, there is obviously no sound without

timbre (pp. 39^40), his interest is in the possibil-

ity of timbre without sound, by which he

means before sound. Nancy expands on the

fact that Timbre is above all the unity of a

diversity that its unity does not absorb (p. 41),

469

an emergent property of music, singular in

quality and multiple in composition. This is

why, as Nancy notes, timbre draws music into

other perceptible registers (p. 42), namely the

metaphors associated with and coming from

other modalities and senses. It draws music

into the wider world (p. 84 n. 36).

This might be taken to be the heart of

Nancys argument: the irruption of ethics into

aesthetics. Nancy says: I would say that timbre

is communication of the incommunicable:

provided that it is understood that the incom-

municable is nothing other, in a perfectly

logical way, than communication itself (p. 40).

Indeed, it should be noted that Nancy writes,

in words hinting at the opening of a community

and thence a sociology of music listeners, that

sonorous presence is a place-of-its-own-self, a

place as relation to self, as the taking-place of a

self, a vibrant place as the diapason of a subject

or, better, as a diapason-subject. (The subject,

a diapason? Each subject, a differently tuned

diapason? Tuned to selfbut without a known

frequency?) (pp. 16^17).

The second and third essays in Listening are

much shorter than the first. March in Spirit in

Our Ranks makes a historical point. After a

prologue referring to Nietzsches Bizet, Nancy

states: not only did Nazism treat and mistreat

in its way the musical art it found before it . . . ;

but Nazism also benefited from an encounter,

which was not a chance one, with a certain

musical disposition, just as it also benefited

from a similar encounter with a certain new

condition, often the most modern, of dance and

of architecture (p. 50). Nancy describes music

as an art of expansion, and as dangerously

implicated in the propagation of a subjectivity

(p. 51). This darker side to the obsession with

musical subjectivity and subject position

provides him with a clue to the ways in which

subjectivity is historically determined and con-

tingent upon particular ideologies, the narra-

tive of which he describes as follows:

conquest transforms its schema in a radical

way: mastery of a territory (one that is rela-

tively indifferent to the capture of souls), and

even the submission and domination of popula-

tions, are followed by the capture and penetra-

tion of identities. Capture gives way to control,

absorption to administration, penetration to

simple jurisdiction (p. 52). Nancy notes

Goebbelss comment that Art is nothing other

than what shapes feeling. It comes from feeling

and not from intelligence (quoted on p. 56), in

order to argue that if this is the case, then the

problem is that the operation [of forming

communities around and upon music] passes

through music (or any art) and over it: the

direction that forms it is added to it as a

finality that music itself does not have. The inef-

fable is charged with speaking (pp. 56^7). This

creates impossible demands for justice in which

feelings cannot be spoken of without being

silenced or betrayed. Nancy concludes the essay

by remarking that What truly betrays music

and diverts or perverts the movement of its

modern history is the extent to which it is

indexed to a mode of signification and not to a

mode of sensibility. Or else the extent to which

a signification overlays and captures a sensibil-

ity (p. 57), and ignores its resonance.

The third essay, How Music Listens to

Itself , reads like a refraction of the argument

in Listening. Nancy starts with a straw man

position: somebody who listens without

knowing anything about itas we say of those

who have no knowledge of musicology (p. 63).

The rhetoric is couched in negative terms, and

it would be useful to develop the mirror image

of this description, namely a sense of what the

non-specialist listener does (rather than does

not) and is (rather than is not). The straw man

position adopted by Nancy generates, almost

automatically, a series of oppositions or differ-

ences, which he works over towards a feeling

for the aesthetic work they might produce.

Thus, for example, Nancy writes that musical

listening allows one to link sensory apprehen-

sion to analysis of composition and execution

(p. 63), while a little further on he asks, How

are the musicianly and the musical shared or

intermingled? (p. 64), describing the pair as a

technical apprehension and a sensory apprehen-

sion (p. 64). Nancys conclusion is reasonable:

musical listening worthy of that name can

consist only in a correct combination of the

two approaches or of the two dispositions, the

compositional and the sensory (pp. 63^4).

In summary, Listening is a careful working

through of the ears essential mechanisms

that unfolds alongside the errors of post-

Enlightenment Western thought and opens up

new soundscapes for listening. Along the way,

it affords a new form of subject phrase in the

resonance of feelings and their linkages, and

shows how resonance articulates feeling, how

feelings become phrases, and how articulating

phraseslisteningmight actually be ethical,

prudent, and sensitive to the event. Like

Andrew Bowies magisterial Music, Philosophy,

and Modernity (Cambridge, 2007; reviewed by

James Garratt in this volume, p. 429), though in

a quite different register, it demonstrates that

470

music has a thing or two to teach us, whether

we are philosophers, musicians, both, or neither.

ANTHONY GRITTEN

Middlesex University

doi:10.1093/ml/gcq035

The Rock Canon: Canonical Values in the Reception of

Rock Albums. By Carys Wyn Jones. pp.

xii 169. Ashgate Popular and Folk Music

Series. (Ashgate, Aldershot and Burlington,

Vt., 2008, 50. ISBN 978-0-7546-6244-0.)

Talking to The Guardian newspaper in 2002, the

poet and critic Tom Paulin complained about

A-level, the British school-leaving examination

that prepares for university: I think A-level

History is still a very good subject, but English

is very watery now. Alan Bennett is on the cur-

riculum, for fucks sake! Imagine giving an

18-year-old Alan Bennetts monologues. From

such tiny seeds do canons grow: taste strutting

around as value, highbrow sneering at

best-selling author much admired, and the

public, national playground of school, with its

door-opening qualifications, student numbers

by the busload, bonanza sales for authors who

luck out. The Rock Canon plunges energetically

into these watery waters, figuring how

so-called popular music finds itself saddled

with an idea lumbered with the baggage of

English literature and so-called classical music.

The Rock Canon was Carys Wyn Joness

doctoral thesis at Cardiff, where her daily work

centred on ten records and the critical writing

around them. The choice of albums matters a

lot, and is mostly the hundred greatest albums

ever made as voted by critics for Dadrock

magazine Mojo in August 1995, corroborated

by statistician Henrik Franzon (pp. 26^7).

Alongside the writing specific to the albums,

including single-author monographs, reference

is made to other commentaries: essays in The

Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock and Roll,

for example, or, with curious frequency, John

Lennons 1970 interview with Jann Wenner for

Rolling Stone magazine. All this is of great

interest for those about to rock, as Brian

Johnson would say, but perhaps few besides.

However, another cluster of literature presents

the material alongside debates in musicology

referring to classical music, writers such as

Joseph Kerman, Marcia Citron, and William

Weber, and edited collections Disciplining Music

(1992) and The Musical Work (2000). Finally, a

first chapter brings on debates around the

canon in literary studies, writers such as

Harold Bloom, Frank Kermode, Barbara

Herrnstein Smith, and John Guillory, both his

useful article in Critical Terms for Literary Study

(1990) and impenetrable book, Cultural Capital

(1993). Thus The Rock Canon should prove useful

both for courses limited to popular music, and

for courses in musicology that aim to take a

broad or long view; it is also a subject of intrin-

sic and general interest.

The first chapter, Defining the canon, is a

handy summary recommended for students

working to an essay deadline and teachers

looking for a rapid seminar fix. Over the fol-

lowing three chapters, the ten albums and their

critics take centre-stage, as Wyn Jones looks for

aspects of canon formation in rock music

similar to and different from those of literature

or classical music. Among many others, useful

and interesting topics include genius, art, influ-

ence, the test of time, romantic myths of creativ-

ity, and list-making. A fifth chapter examines

the relationship between what Clive James

termed the metropolitan critic and writers

based in universities (Tom Paulin straddles

both). The final chapter betrays its roots in

academic examination, with unnecessarily

tepid conclusions, such as: there is a case for

and against a canon in rock music (p. 139)

andsomething so winsome Princess Di might

have said ithaving a canon of albums might

ultimately be a matter of individual perception

(p. 139). We dont really find out what Wyn

Jones thinks; right-on enough to declare canon

to be inherently elitist (p. 25), and temporary,

contingent, and subjective (p. 15), but good-

girl enough to insist that a field without

categories is simply a mess (p. 140). Consider-

able time and effort may have gone in establish-

ing only something non-contentious from the

start: when asked, and as part of the job, critics

postulate, parade, police, and pooh-pooh histor-

ically transcendent value judgements. Its inter-

esting and salutary to learn that writers on

Anglo-American rock music use ideas similar

to those used of classical and romantic music,

and The Rock Canon is, if nothing else, a

splendid digest of hacks trembling before their

favourite records: the prize goes to Amy

Raphael on the Stone Roses (what we are left

with is the art, the music, p. 97). This aspect is

often expertly done: see the eagle eye for the

slack use of quantum leap (at p. 59), or Patti

Smiths use of the word canonizing on the

sleeve-note of Horses (at p. 76). Readers might

want to read Wyn Jones and her critics along-

side an underrated book, Robert Pattisons The

471

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Online Application Guide for S&I Selection ProcessDocument10 pagesOnline Application Guide for S&I Selection ProcessungulataNo ratings yet

- 978 962 996 435 1 PrefaceDocument35 pages978 962 996 435 1 PrefaceungulataNo ratings yet

- Wai-Lim Yip - Diffusion of DistancesDocument267 pagesWai-Lim Yip - Diffusion of DistancesungulataNo ratings yet

- Graduation Project on Anne Frank and Journey to the WestDocument1 pageGraduation Project on Anne Frank and Journey to the WestungulataNo ratings yet

- Week Month Events Public Holidays / Students' Recess: First Working Day After Immaculate ConceptionDocument2 pagesWeek Month Events Public Holidays / Students' Recess: First Working Day After Immaculate ConceptionungulataNo ratings yet

- Portable Computer DistributionDocument4 pagesPortable Computer DistributionungulataNo ratings yet

- Academic Calendar 2014/2015: August 2014Document2 pagesAcademic Calendar 2014/2015: August 2014ungulataNo ratings yet

- Second Book of Sanskrit - RG Bhandarkar - OriginalDocument220 pagesSecond Book of Sanskrit - RG Bhandarkar - Originalungulata100% (1)

- The Rhetoricity of Ovid's Construction of ExileDocument77 pagesThe Rhetoricity of Ovid's Construction of ExileungulataNo ratings yet

- A Practical Grammar of The Sanskrit LanguageDocument408 pagesA Practical Grammar of The Sanskrit LanguageungulataNo ratings yet

- Translating PaceDocument4 pagesTranslating PaceungulataNo ratings yet

- Form and Spirit in Poetry TranslationDocument12 pagesForm and Spirit in Poetry TranslationungulataNo ratings yet

- Redefining Chinese CitizenshipDocument17 pagesRedefining Chinese CitizenshipungulataNo ratings yet

- IslamDocument145 pagesIslamHaneefa Ch100% (8)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Blinded Tab by As I Lay Dying - Rhythm L - Distortion Guitar Songsterr Tabs With Rhythm 2Document1 pageBlinded Tab by As I Lay Dying - Rhythm L - Distortion Guitar Songsterr Tabs With Rhythm 2Daniel GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Satellite CommunicationsDocument14 pagesSatellite CommunicationsNicole ButlerNo ratings yet

- Euphoria 106 The Next Episode 2019Document67 pagesEuphoria 106 The Next Episode 2019Ahmed SamehNo ratings yet

- YAMAHA YAS-62 ManualDocument12 pagesYAMAHA YAS-62 ManualTimikiti JaronitiNo ratings yet

- I and You: Lauren GundersonDocument68 pagesI and You: Lauren Gundersonalioliver9100% (4)

- Art Appreciation 5Document8 pagesArt Appreciation 5Asher SarcenoNo ratings yet

- Being The SolutionDocument46 pagesBeing The Solutionsheelam54761No ratings yet

- Hall V Swift DismissalDocument16 pagesHall V Swift DismissalTHROnline100% (6)

- File Test 3 Grammar, Vocabulary, and Pronunciation ADocument6 pagesFile Test 3 Grammar, Vocabulary, and Pronunciation ASofia Llanos0% (1)

- GSM Mobile CommunicationsDocument81 pagesGSM Mobile CommunicationsPalash Sarkar100% (1)

- Test OdtDocument4 pagesTest OdtkanwaljitsinghchanneyNo ratings yet

- Academy Travel Tour Program January To December 2020Document100 pagesAcademy Travel Tour Program January To December 2020dieschnelleNo ratings yet

- CENTURY OF REVOLUTION (Music Edition) - Assignment 2 For Music Appreciation 1Document30 pagesCENTURY OF REVOLUTION (Music Edition) - Assignment 2 For Music Appreciation 1xan chong zhu XuNo ratings yet

- Ia - Electronics LM Grade 7 & 8 P&DDocument124 pagesIa - Electronics LM Grade 7 & 8 P&DAngel Jr Arizo Lim82% (11)

- Gumshoe 1st 10 PagesDocument11 pagesGumshoe 1st 10 PagesPat DowningNo ratings yet

- LAS PLAYAS DE RIO (Guion) PDFDocument40 pagesLAS PLAYAS DE RIO (Guion) PDFAngel Ibañez BlesaNo ratings yet

- Case Studies On Descriptive StatisticsDocument4 pagesCase Studies On Descriptive StatisticsSHIKHA CHAUHANNo ratings yet

- Total Shuffled World TourDocument498 pagesTotal Shuffled World TourIndira Luz Sanchez AlbornozNo ratings yet

- Conjunctions Test with Cool MusicDocument4 pagesConjunctions Test with Cool Musicjaffar wamaiNo ratings yet

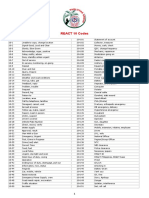

- React 10 Codes PDFDocument2 pagesReact 10 Codes PDFPaul Anselmo Dela Cruz100% (3)

- The Butch ManualDocument121 pagesThe Butch Manualfreakazoid66624% (38)

- Sound Development: Warm-Up Exercises For Tone and TechniqueDocument4 pagesSound Development: Warm-Up Exercises For Tone and TechniqueEmmanuel Camelo QuinteroNo ratings yet

- BRTL32 BDA User ManualDocument3 pagesBRTL32 BDA User Manualkhoalang202No ratings yet

- Boplicity MulliganDocument4 pagesBoplicity MulliganAnonymous mWKciEMJ4yNo ratings yet

- Ancient dance history and benefits of movementDocument3 pagesAncient dance history and benefits of movementKrystal JungNo ratings yet

- REQUEST LETTER DRRMDocument2 pagesREQUEST LETTER DRRMJayson Catungal100% (1)

- (Clarinet - Institute) Klose - Complete Method For The Clarinet PDFDocument194 pages(Clarinet - Institute) Klose - Complete Method For The Clarinet PDFAndres Jimenez Garcia100% (1)

- Filipino artists and awardeesDocument1 pageFilipino artists and awardeesLiza Joy A. RamirezNo ratings yet

- Stone Sour TaciturnDocument6 pagesStone Sour TaciturnDavid NewmanNo ratings yet

- Ryanair Magazine January-February 2012Document154 pagesRyanair Magazine January-February 2012Sampaio RodriguesNo ratings yet