Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Food Away From Home

Uploaded by

ch_yepCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Food Away From Home

Uploaded by

ch_yepCopyright:

Available Formats

Determinants of Malaysian Household Expenditures of

Food-Away-From-Home

Helen Lee

Former Graduate Research Assistant

School of Social Sciences

Universiti Sains Malaysia

11800 Minden, Penang

Malaysia

Email: ngandy76@hotmail.com

Andrew Tan

Senior Lecturer

School of Social Sciences

Universiti Sains Malaysia

11800 Minden, Penang

Malaysia

Email: atan@usm.my

Contributed paper prepared for presentation at the International Association of

Agricultural Economists Conference, Gold Coast, Australia,

August 12-18, 2006

Copyright 2006 by Helen Lee and Andrew Tan. All right s reserved. Readers may make

verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided

that this copyright notice appears on all such copies.

2

Determinants of Malaysian Household Expenditures of

Food-Away-From-Home

Introduction

Malaysians have traditionally apportioned the largest amount of household

expenditures on food products. This includes consumption of food-at-home (FAH) and

food-away-from-home (FAFH). However, while spending on FAH has declined steadily

from a share of 33.7% in 1973 to 22.2% in 1999, spending on FAFH rose from 4.6% in

1973 to 10.9% in 1999 (Department of St atistics Malaysia 2000). This reflects the

changing lifestyle of Malaysian households, whereby, having a meal at home is becoming

less often while eating out has become more frequent.

As Malaysians eat out more often, this has paved the way for the development of

the FAFH industry. From 1999-2003, the Malaysian consumer foodservice market

increased by 16% to a t otal of 20,235 consumer food service units. During the same

period, consumer food service transactions and market worth grew by 22% and 39%

respectively to 1,026 million and RM16,312 million (US$4,315 million) in current value

terms. The home delivery or take-away food sector also grew by 60% in unit terms from

1999-2003 due to the increasingly busy work schedules of Malaysian households.

Besides the fast-food sector, cafs and street st alls also registered high growth rates in

unit terms over the period of 1999-2003 (Euromoniter International Report, 2004).

Despite its upward growth trend and economic significance, certain aspects of the

Malaysian FAFH industry have been neglected over the years. While micro-level demand

studies of FAFH in Western cultures have been extensively conducted using household

consumption data (Stewart et al., 2004; Capps, Jr., and Park, 1997; Byrne et al., 1996;

McCracken and Brandt, 1987; Redman, 1980), an extensive review of the literature

3

revealed that little or no research attention has been devoted to examining the FAFH

consumption patterns of gastronomes in the local region. By simply concluding that

demand is on the uptrend and will likely continue to do so in the near future would be

impetuous, as little is known about the drivers of the consumer demand function related

to changes in the socio-demographic characteristics of the Malaysian population.

As such, this study aims to gain a better understanding of how socio-demographic

factors influence the amount of money spent on FAFH in Malaysia. Understanding how

these factors affect household expenditure patterns on FAFH is important to food service

strategy and consumer insight analysts who are interested in knowing the characteristics

that define their industry. In addition, a better understanding of these factors enables the

public authorities to be aware of the structure of the food distribution industry and

nutritional intake of Malaysian households.

Theoretical Framework

Beckers (1965) theory of household production is often used to model household

expenditure analysis. The theory extends to consider how households choose the best

combination of commodities to maximize utility, while subject to time, resources, and

technology constraints. Following Manrique and Jensen (1998), a household maximizes:

U = U(Z

1

, Z

2

, , Z

j

, , Z

n

) (1)

where, U = household utility function; and, Z

j

= quantities of home-produced commodity

j. This function is subject to constraints such as tot al time available for the household

4

(opportunity cost of time), total expenditures on market-purchased good being equal to

the sum of non-wage income and wage income of household members, and household

characteristics (Manrique and Jensen, 1998).

From the solution of (1) using cross-sectional data, Manrique and Jensen (1998)

noted that the following expenditure function can be derived:

E

i

=

i

(T, M, d) i = 1, 2, , n (2)

where, E

i

= total household expenditures for the i

th

household; T = the hours of

participation in the workforce by the i

th

household; M = wage and non-wage income for

the i

th

household; and, d

= a vector of socio-demographic variables (e.g. age, gender, race,

household size) hypothesized to affect the households expenditures on a particular good.

Empirical Model

In this study, the dependent variable (Y

i

) measures the total monthly household

expenditures by the i

th

respondent on FAFH. Given the nature of disaggregated cross-

sectional data, it is conceivable that households not recording any FAFH expenditures

during the specified survey period but otherwise having complete records of socio-

demographic characteristics are included in the sample. Total expenditures containing

zero as well as positive amounts are consequently distributed over a limited range

1

. In

such instances, the censored Tobit model (Tobin, 1958) is appropriate given that its

1

However, altering or disposing of such zero observations results in the loss of valuable information on

users and non-users (Heckman, 1979). The use of ordinary least squares regression, on the other hand,

results in biased, inconsistent, and inefficient parameter estimates (Greene, 2003).

5

specifications allow for the presence of zero observations attributable to corner solutions.

The standard censored or Tobit model for the research study is written as:

Y

i

*

= X

i

'

+ u

i

, i = 1, 2, , n

Y

i

= Y

i

*

if Y

i

*

> 0, (3)

Y

i

= 0 if Y

i

*

0,

where, Y

i

= observed dependent variable (total monthly household FAFH expenditures);

Y

i

*

= latent variable (the optimal amount of expenditures of the respondent or the

solution to a utility maximization problem);

'

i

X = k -dimensional vector of socio-

demographic regressors as listed in Table 1; = k -dimensional vector of unknown

parameters; u

i

= stochastic disturbance term assumed to be N(0,

2

).

The maximum likelihood method is used to estimate the coefficients. Since this

method assures the consistency of large sample and the asymptotic normality of the

estimated coefficients, conventional tests of significance are applicable. The likelihood

function for the Tobit model is given by:

L

X Y X

i i i

( )

( )

' '

_

,

1

]

1

1

]

1

1

0

1

1

, (4)

where,

0

= the product over values of i where

*

i

y 0;

1

= the product over values

of i where

*

i

y > 0; = (

2 '

, ); and and = cumulative distribution function and

probability density function, respectively, of the standard normal variable (Greene, 2003).

6

Model Regressors

The selection of variables likely to influence Malaysian household expenditures

on FAFH relies on the previous studies by Stewart et al. (2004), Capps, Jr., and Park

(1997), Byrne et al. (1996), Capps, Jr. et al. (1985), McCracken and Brandt (1987), and

Redman (1980). The following socio-demographic characteristics are therefore

hypothesized to influence the amount of money spent on FAFH in the current study: (1)

age of household head or meal planner, (2) location, (3) ethnicity/race, (4) gender, (5)

education level, (6) total monthly household income, and (7) household size (Table 1).

INSERT TABLE 1

Age of household head (in years) is selected as an explanatory variable in the

current study as Capps, Jr., and Park, (1997) and McCracken and Brandt (1987) have

shown that both younger and older people are assumed to have differences in tastes and

preferences for food, eating habits, lifestyles, and opportunities to socialize. In addition,

given the fast paced routines and tight schedules rising from rapid structural

transformation and urbanization process that Malaysia is currently undergoing,

households may find it hard to break the eating out cycle as consumers demand fast and

easy meal solutions t o fit their busy lifestyles. Hence, the convenience of FAFH serves as

an attractive option to most urban households that face production time constraints.

(Mihalopoulos and Demoussis, 2001; Nayga, Jr. and Capps, Jr., 1993).

McCracken and Brandt (1990) suggest that a dummy variable based on ethnicity

be included in household food expenditure studies to allow for the possibility of cultural

7

and ethnic differences to influence purchase decisions. Therefore, ethnicity is grouped

under Malay (Race1), Chinese (Race2), and Indian/others (Race3) (base group) in the

present study given the unique Malaysian scenario of three distinct races amongst its

multi-ethnic population (i.e. Malay, Chinese, Indian and a small proportion consisting

those of various other races). At the same time, gender of hous ehold head is selected as

one of the dummy explanatory variables in the current study as participation rates of

women in the Malaysian workforce have been st eadily increasing from 44.8% in 2000 to

46.7% in 2004 (Ministry of Finance Malaysia, 2004). This emerging trend may lead to an

increase in demand for FAFH amongst women and households who have less time to

cook at home (Binkley, 2005; Byrne, et al. 1996; Nayga, Jr. and Capps, Jr. 1993).

Formal education of the household head (in number of years) is another

explanatory variable selected in this study due to its effect on lifestyles and health-related

behaviours. Individuals with different levels of education may have different knowledge

and perception about diet and health, and consequently may perceive FAFH in different

manners. This variable also acts as a proxy for the opportunity cost of time since the data

does not have information on the number of hours worked. In essence, higher educated

respondents have higher opportunity cost of time and may prefer to eat out more often.

Similarly, total gross monthly household income (in RM) is used as an

explanatory variable in the current study. While wealthier households are assumed to

spend more on products and services (including leisure and other dining amenities such

as full service and ambience), consuming FAFH may be considered as a form of leisure

as well (Binkley, 2005; Stewart et al., 2004; Mihalopoulos and Demoussis, 2001).

Finally, household size may influence FAFH expenditures as larger households have a

8

higher household burden and would be less able to afford the higher cost of eating-out. In

general, food prepared at home may be more economical for larger households.

Furthermore, larger size families with pre-school children may spend less on FAFH due

to the inherent characteristics of small children themselves, such as poss ible behavior

problems in restaurants and smaller stomach capacities (Redman, 1980).

Data

The data in this study is from the Malaysian Household Expend iture Survey

1998/1999 (MHES), conducted from July 1998 and continued through June 1999 by the

Department of Statistics Malaysia. This secondary data set is the most recent available of

the national household food expenditure survey. The sample was designed using a

stratified multi-stage, area probability sampling method, thus ensuring that socio-

demographic and geographical considerations are taken into account to reflect the

Malaysian population. Household heads in the survey were asked to record their monthly

expenditures on FAFH, in addition to information on their socio-demographic

characteristics

2

. From the total number of 9198 households, only 9184 were retained for

this study after discarding those with suspect or incomplete information.

Characteristi cs of Survey Respondents

The descriptive statistics of variables in the statistical models are presented in

Tables 2. For the total sample, the average age of the household head is 44.8 years, with

the youngest being 16 years old and the oldest 98 years old. About 57% of the total

2

Respondents not recording purchases during the specified period but having otherwise complete records

of soci oeconomic and demographic characteristics are included in the sample. Monthly expenditures

containing zero as well as positive (RM) amounts are thus consequently distributed over a limited range.

9

sample resides in urban areas while 43% reside in rural areas. In terms of ethnicity, 50%

of the entire sample household heads are Malay; 29% Chinese; and 21% Indian/other

races. The whole sample consists of about 83% male and 17% female household heads,

with an average household size of approximately 4 persons, consisting of a single person

to 23 persons in a household (Table 2). From the sub-sample, whereby respondents are

categorized under FAFH purchasers or non-purchasers, 6608 (72%) respondents reported

that they purchased FAFH, while 2576 (28%) respondents reported that they did not

purchase any FAFH at all during the survey period (Table 2)

3

.

INSERT TABLE 2

Estimation Results

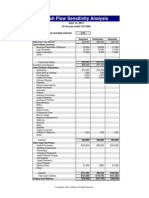

Summary statistics of the Tobit model are reported in Table 3, with the estimated

coefficients () and the probability for z-statistic presented in the first and the second

columns, respectively. Based on McDonald and Moffitt (1980), the marginal effect of

each of the explanatory variables on the expected value of the dependent variable

(amount of expenses evaluated at the means) for all observations (third column) and for

observations above the limit (fourth column) are also presented. The fifth column depicts

the marginal effect on changes in the probability for those who did not spend on FAFH,

but might, thus referring to those observations at the limit

4

.

3

In this study, respondents reporting FAFH expenditures of RM30.00 (US$8) and below were also

classified as non-purchasers. This amount was derived based on a nominal amount of spending of RM1.00

(US$0.26) per day for subsistence spending awayfrom home.

4

A more comprehensive discussion of the results of the Tobit analysis can be obtained from the authors

upon request.

10

Out of the total of nine explanatory variables, only location, Race2 (Chinese) and

household income are statistically significant in explaining household expenditures on

FAFH. In contrast, the variables that are statistically insignificant are age, Race1

(Malay), Race3 (Indian), gender, education level, and household size. The Log

Likelihood Ratio (LR) and Wald statistics are 1924.852 and 246.518, with probability

values of almost zero. Hence, the model is concluded as having a good fit.

INSERT TABLE 3

Conclusions and Policy Implications

Results of this study may have important implications for the food industry in

Malaysia as it indicates that household income, race, or location of residence of

households significantly affect total monthly expenditures on FAFH, ceteris paribus.

Specifically, as household income increases, total monthly expenditures on FAFH are

expected to increase. At the same time, Chinese households or urban residents have

significantly higher FAFH expenditures than their non-Chinese or rural counterparts.

Several notable implications can be culled from these results. First, similar to the

trend in other countries, it is expected that the shift in Malaysian food expenditure

patterns toward FAFH will continue to transpire with increased income and urbanization

arising from economic growth. As such, this provides great business opportunities for the

development of the away-from-home foodservice industry in Malaysia. Second, when

considering the viability of future business locations, the foodservice industry may target

markets consisting of ethnic Chinese households, urban locales, or those with high

disposable incomes. These socio-demographic characteristics are found to define those

11

who are willing and able to spend on FAFH to satisfy their lifestyle and nutritional needs.

Third, since FAFH is typically high in fat, sodium, and calories content, public health

policies aimed at ensuring optimal nutrient intake should target Chinese households and

those in the urban settings to be more selective of their dietary intake. Fourth, more food

review columns in popular Malay and Indian language-based news-media, or even

regional radio advertisement programmes should also be considered in order to promote

FAFH outlets amongst these ethnic groups. At present, such promot ional strategies are

still lacking. Lastly, advertising and promotional efforts focusing on age groups, gender,

or even education may have limited effects on FAFH expenditure patterns.

Finally, while this study acts as a catalyst to further research on Malaysian

household expenditure patterns of FAFH, several limitations exists due to the secondary

nature of the data. First, since only information on the value of total monthly household

expenditures is available, the dependent variable is assumed to implicitly capture the

interaction between prices and quantities (demand) in the FAFH market. Second, while

additional information such as marital status, number of working adults, age and number

of children, purchasing outlet (fastfood, hawker, restaurants), working hours, and reasons

for consumption or non-consumption may provide a more comprehensive indication of

socio-demographic effects, these information were not readily available.

12

References

Becker, G. S. 1965. A Theory of Allocation of Time. Economics Journal, 75: 493-508.

Binkley, J.K., 2005. The Effect of Demographic, Economic, and Nutrition Factors on the

Frequency of Food Away from Home. Selected paper presented at the American

Agricultural Economics Association Annual Meetings, Providence, Rhode Island,

July 24-27, 2005.

Byrne, P.J., O. Capps, Jr. and A. Saha. 1996. Analysis of Food-Away-From-Home

Expenditure Patterns for U.S. Households, 1982-89. American Journal of

Agricultural Economics, 78, pp. 614-627.

Capps, Jr., O. and L.J. Park. 1997. Demand for Prepared Meals by U.S. Households.

American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 79, pp. 814-824.

Capps, Jr., O., J.R. Tedford and J. Havlicek, Jr. 1985. Household Demand for

Convenience and Nonconvenience Foods. American Journal of Agricultural

Economics, 67, pp. 862-869.

Department of Statistics Malaysia. 2000. Report on Household Expenditure Survey,

Malaysia (1998/99). Department of Statistics Malaysia, Putrajaya, Malaysia.

Euromonitor International Report. 2004. Executive Summary, April. [Internet] Available

from: <http://www.euromonitor.com/Consumer_Foodservice_in Malaysia>

[Accessed 14 May 2005].

Greene, W.H. 2003. Econometric Analysis. 5

th

Edition. United States of America:

Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

Heckman, J.J. 1979. Sample Selection Bias as a Specification Error. Econometrica, 47,

pp. 153-161.

Manrique, J. and H.H. Jensen. 2001. Spanish Household Demand for Seafood Products.

Journal of Agricultural Economics. 52:23-37.

Ministry of Finance Malaysia. 2004. Economic Report 2004/2005. Kuala Lumpur,

Malaysia.

McCracken, V.A. and J.A. Brandt. 1987. Household Consumption of Food Away From

Home: Total expenditure and by type of food facility. American Journal of

Agricultural Economics, 69, pp. 274-284.

McDonald, J.F. and R.A. Moffitt. 1980. The Uses of Tobit Analysis. Review of

Economics and Statistics, 60, pp. 318-321.

13

Mihalopoulos, V.G. and M.P. Demoussis. 2001. Greek Household Consumption of Food

Away from Home: A Microeconometric Approach. European Review of

Agricultural Economics, 28, pp. 421-432.

Nayga, Jr., R.M. and O. Capps, Jr. 1993. Analysis of Socio-Economic and Demographic

Factors Affecting Food Away from Home Consumption. Journal of Food

Distribution Research, 24, pp. 69-86.

Redman, B.J. 1980. The Impact of Women s Time Allocation on Expenditure for Meals

Away From Home and Prepared Foods. American Journal of Agricultural

Economics, 62, pp. 234-237.

Stewart, H., N. Blisard, S. Bhuyan, and R. Nayga, Jr. 2004. The Demand for Food Away

From Home: Full-Service or Fast Food? [Internet] Available from:

<http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/AER829/> [Accessed 15 November 2004]

Tobin, J. 1958. Estimation of Relationships for Limited Dependent Variables.

Econometrica, 26, pp. 24-36.

14

Table 1

Description of Explanatory Variables in the Statistical Model

Variable Description

Age Age of household head (in years)

Race1 1 if Malay household head; 0 if non-Malay

Race2 1 if Chinese household head; 0 if non-Chinese

Race3 1 if Indian/other household head; 0 if non-Indian/other

Education Formal education of the household head (in years)

Gender 1 if male household head; 0 if female

Household Size Total number of family members in the household

Household Income Total gross monthly household income (in Ringgit)

Location 1 if household resides in urban area; 0 if rural

15

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics of Variables in the Statistical Models

Those who Those who

purchased FAFH DID NOT purchase FAFH Total Sample Population

(n

1

= 6608) (n

2

= 2576) (N = 9184) Average

Variables Mean Min Max Mean Min Max Mean Min Max

Tot. Expenditures (RM) 197.63 30 5311.9 - - - 142.20 0 5311.9 1621.00

Age (years) 43.66 16 91 47.70 16 98 44.80 16 98 26.3

Race1 (dummy) 0.49 0 1 0.52 0 1 0.50 0 1 54%

Race2 (dummy) 0.35 0 1 0.12 0 1 0.29 0 1 26%

Race3 (dummy)

*

0.16 0 1 0.36 0 1 0.21 0 1 20%

Education (years) 8.74 0 17 5.75 0 17 7.90 0 17 -n/a-

Gender (dummy) 0.85 0 1 0.79 0 1 0.83 0 1 50.4%

Household Size (no. occup) 4.43 1 23 4.26 1 17 4.40 1 23 4.6

Household Income (RM) 2776.14 1 56638 1197.56 64 55000 2333.36 1 56638 2472.00

Location (dummy) 0.65 0 1 0.36 0 1 0.57 0 1 62%

* Refers to the omit ted category in the analysis

16

Table 4

Summary Statistics for Tobit Analysis of

Household Expenditures on FAFH

1 2 3 4 5

Explanatory

Variables

Coefficients

()

Z-statist.

i

X

E(Y)

i

X

0) Y E(Y

> |

i

X

0) P(Y

>

Constant -1.4387 -0.0384 -0.9161 -0.6398 -0.0014

Age -0.5833 -1.0689 -0.3714 -0.2594 -0.0006

Race1 13.8761 0.8096 8.8363 6.1706 0.0134

Race2 122.9893 6.6376* 78.3196 54.6930 0.1186

Education 2.0601 1.1748 1.3119 0.9161 0.0020

Gender 19.8454 1.0392 12.6376 8.8252 0.0191

Household Size -3.2764 -1.1026 -2.0864 -1.4570 -0.0032

Household Income 0.0357 36.3021* 0.0227 0.0159 0.00003

Location 36.9724 2.4913* 23.5440 16.4415 0.0356

Note: The unconditional expected value of y (at mean x) = 233.593; the conditional expected value of y

(at mean x) = 366.82317; the standard error around the Tobit model index = 389.2126; the predicted

probability that y>0 (at the mean x) = 0.6368; z = 0.35; f(z) = 0.3752.

* at 5% level of significance

Source: Columns 3-5 computed by authors

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Microsoft Academy Return On Investment (ROI) White Paper CalculatorDocument3 pagesMicrosoft Academy Return On Investment (ROI) White Paper Calculatorch_yepNo ratings yet

- Financial KpiDocument4 pagesFinancial Kpich_yepNo ratings yet

- Accounting KpiDocument5 pagesAccounting Kpich_yepNo ratings yet

- Makakalikasan SSG Ppa Accomplishment Report Template EditedDocument4 pagesMakakalikasan SSG Ppa Accomplishment Report Template Editedjunapoblacio100% (3)

- Fire Extinguisher Training Manual v2 1Document12 pagesFire Extinguisher Training Manual v2 1ch_yep100% (1)

- Cash Flow Sensitivity AnalysisDocument1 pageCash Flow Sensitivity Analysisch_yepNo ratings yet

- Discounted Dividend Valuation USDocument9 pagesDiscounted Dividend Valuation USch_yepNo ratings yet

- Present5 Sensitivity AnalysisDocument8 pagesPresent5 Sensitivity Analysisch_yepNo ratings yet

- Ver. Per Month USDocument30 pagesVer. Per Month USch_yepNo ratings yet

- How To Identify Food Trends White PaperDocument11 pagesHow To Identify Food Trends White Paperch_yepNo ratings yet

- Sales KpisDocument8 pagesSales Kpisch_yepNo ratings yet

- Production KpisDocument15 pagesProduction Kpisch_yepNo ratings yet

- 09 Standardized Drink and Product AbbreviationsDocument1 page09 Standardized Drink and Product Abbreviationsch_yepNo ratings yet

- Phone Answering and Reservation ProcedureDocument2 pagesPhone Answering and Reservation Procedurech_yepNo ratings yet

- Checklist For Registration Under Section 54Document1 pageChecklist For Registration Under Section 54ch_yep0% (1)

- List Off From JakimDocument14 pagesList Off From Jakimch_yepNo ratings yet

- Employee Vacation Requests: Department Name: Supervisor NameDocument1 pageEmployee Vacation Requests: Department Name: Supervisor Namech_yepNo ratings yet

- Procedures For Cleaning Ice MachinesDocument2 pagesProcedures For Cleaning Ice Machinesch_yepNo ratings yet

- Nagomi Standard Operation Procedure: Prawn. Are You Allergic To Any Other Kind of Seafood?" Asking Questions WillDocument1 pageNagomi Standard Operation Procedure: Prawn. Are You Allergic To Any Other Kind of Seafood?" Asking Questions Willch_yepNo ratings yet

- Rs Op 13 Pest ControlDocument2 pagesRs Op 13 Pest Controlch_yepNo ratings yet

- Chemical Dish Machine Monitoring Form: Restaurant Name: - Month, YearDocument2 pagesChemical Dish Machine Monitoring Form: Restaurant Name: - Month, Yearch_yepNo ratings yet

- Personnel Planning and Recruiting: Chapter-5Document15 pagesPersonnel Planning and Recruiting: Chapter-5Dayittohin JahidNo ratings yet

- Org Management Week 10Document15 pagesOrg Management Week 10Jade Lyn LopezNo ratings yet

- Deregulation of Essential CommoditiesDocument130 pagesDeregulation of Essential CommoditiesRajagopal RaoNo ratings yet

- 0445 IV Semester 5 Year B.B.A. LL.B. (Hons.) Examination, Dec. 2012 International BusinessDocument11 pages0445 IV Semester 5 Year B.B.A. LL.B. (Hons.) Examination, Dec. 2012 International Business18651 SYEDA AFSHANNo ratings yet

- Natural Ice CreamDocument12 pagesNatural Ice CreamAkash Malik0% (1)

- Exercise - Sesi 11Document2 pagesExercise - Sesi 11GomiNo ratings yet

- Q2e LS5 U07 VideoTranscriptDocument2 pagesQ2e LS5 U07 VideoTranscriptTrần Chí Bảo XuyênNo ratings yet

- Ifs Cia 1Document12 pagesIfs Cia 1sachith chandrasekaranNo ratings yet

- Farewell Address WorksheetDocument3 pagesFarewell Address Worksheetapi-261464658No ratings yet

- Arrow and The Apparel IndustryDocument6 pagesArrow and The Apparel IndustryShikha Prakash0% (1)

- Managerial Remuneration Checklist FinalDocument4 pagesManagerial Remuneration Checklist FinaldhuvadpratikNo ratings yet

- Case 1 AnswersDocument3 pagesCase 1 AnswersMuhammad SulemanNo ratings yet

- Surf ExcelDocument13 pagesSurf Excelpushkargtm100% (2)

- Cma Intermediate Youtube Faculties LinksDocument6 pagesCma Intermediate Youtube Faculties LinksPAVITHRA MURUGANNo ratings yet

- India Map in Tamil HDDocument5 pagesIndia Map in Tamil HDGopinathan M0% (1)

- Car Policy 2022 - 2023Document2 pagesCar Policy 2022 - 2023Shakshi TomarNo ratings yet

- Alice's Adventures in WonderlandDocument2 pagesAlice's Adventures in WonderlandDavid SaguaNo ratings yet

- Price LisDocument9 pagesPrice LisDssp StmpNo ratings yet

- CIR Vs Kudos, GR 178087, May 5, 2010Document4 pagesCIR Vs Kudos, GR 178087, May 5, 2010katentom-1No ratings yet

- SCP APPLIED ECONOMICS LessonDocument6 pagesSCP APPLIED ECONOMICS LessonCamille Flor MagdasalNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument10 pagesReportNeeraj KishoreNo ratings yet

- "Power Genrating Tires ": B.E. Iv Year, Sem-Vii Mechanical EngineeringDocument6 pages"Power Genrating Tires ": B.E. Iv Year, Sem-Vii Mechanical EngineeringKeshav CarpenterNo ratings yet

- Management Accounting Report BudgetDocument42 pagesManagement Accounting Report BudgetBilly Maravillas Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Payment SystemDocument24 pagesPayment SystemTooba HashmiNo ratings yet

- Ref - No. 9895444-17168677-8: Vidavaluru Nuthan Phanidhar ReddyDocument8 pagesRef - No. 9895444-17168677-8: Vidavaluru Nuthan Phanidhar ReddyTrip TechnoNo ratings yet

- Digested CasesDocument36 pagesDigested CasesJepoy Nisperos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Coins PH Buy SellDocument10 pagesCoins PH Buy Selljoshann251No ratings yet

- B-Com-Honors Semester CourseDocument113 pagesB-Com-Honors Semester CourseAakar ManglaNo ratings yet

- Cabinet Members 2020Document2 pagesCabinet Members 2020AMNo ratings yet