Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Scoring Methods for Defects of the Alveolar Process

Uploaded by

WellyAnggaraniOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Scoring Methods for Defects of the Alveolar Process

Uploaded by

WellyAnggaraniCopyright:

Available Formats

D.

Muller

Faculty of De&~,

State Univc*sity at Utrecht,

Sorbonnelaan 16, 3584 CA

Utrecht, The Netherlana!s

The&o l of Defects of the Alveolar

SfI Process in uman Crania

Scoring methods for interalveolar and alveolar resorption, furcation

involvement, fenatrations and dehiscences in the alveolar process of

human skull material are presented.

W. R. K. Perizonius

Institute of Human Biology*,

State Universify at Utwcht,

Achter ae Dom 24, 3512 JP

Utrecht, The Netherlands

Received 21 October 1978

and accepted 26 April 1979

Kcywwak: alveolar resorption,

furcation involvement, fenestra-

tion, dehiscence, periodontal

disease.

In order to obtain consistent paleopathological and/ or paleogenetical data on populations

represented by skeletal remains, it is necessary to use standardized methods of investiga-

tion.

A description will be given of revised methods used to determine the extent of patho-

logic as well as physiologic (with possible genetic background) defects of the alveolar

process in dry skull material. Four types of bony defects are distinguished:

1. interalveolar and alveolar resorption

2. furcation involvement (equivalent to interradicular resorption)

3. fenestration

4. dehiscence.

The first two are lesions typical of periodontal disease. The latter two possibly increase

the susceptibility for periodontal disease, but may be accepted as normal genetic varia-

tions in the bony structure (Schectman, Ammons, Simpson & Page, 1972).

When these four types of defects are scored according to the methods presented, not

only the prevalence of each of these defects in different populations may be calculated but

also information about differences in localization, morphology and/ or severity of the bony

changes is obtained. Paleodemographic (in particular longevity), paleogenetic and

paleoenvironmental (climate, diet, way of life, medical care) data may provide specific

insight into the pathogenesis of these defects, which is not to be obtained from investiga-

tions only of recent populations. Vice versa the study of these defects may contribute to

these paleogenetic and paleoenvironmental data.

The scoring methods are based on the appearance of defects in early medieval crania

from one of the cemeteries (de Heul) of the Dutch Carolingian commercial town

* Supported by grant no. 28-93 of the Netherlands Organization

for the Advancement of Pure Research (Z.W.O.) and by the

Netherlands Foundation for Human Biology.

Paper presented at the 2nd European meeting of the Paleopatho-

logical Association, held in Turin (Italy) on 2&22 October 1978.

Journal qf Human Evolution (1980) 9, 113-l 16

0047-2484/80/020113+04 302.00/O

@ 1980 Academic Press Inc. (London) Limited

114 D. MULLER AND W. R. K. PERIZONIUS

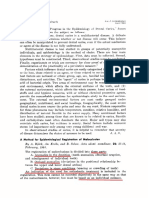

Figure 1. Scoring form with an example.

right

moxillo / mondibulo

left

interolv. defects

(per interolv. ore0 1

olv. resorption

(per tooth in situ )

st. presens (teeth)

St. presens ( proc. olveoloris)

furcotion involvement

(per molar in situ 1

fenestrotion and

dehlscence

(per alveolus 1

max.

man.

Bi

I 4

El8

3 2

El6

. 5

- P

BE

,

Dorestad, recently excavated in the Netherlands. The methods will be explained following

the scoring form (Figure 1).

First the teeth and parts of the alveolar process subject to scoring are presented in a

status presens.

In order to make a detailed scoring of the interalveolar defects the interalveolar area is

devided into 5 sections on the scoring form (Figure 2). The area in which the cortical

plate displays periodontal destruction is shaded. In this way the horizontal distribution of

the defect is indicated. The division of the area is made so that it is possible to denote

specific types of defects as craters, hemisepta and inconsistent margins (Prichard, 1965).

In order to obtain information about the alveolar resorption in a vertical direction, the

distance from the cemento-enamel junction along the root surface to the alveolar crest is

measured (Figure 3). The measurement is done on four sides of each tooth; mesial,

vestibular, distal and lingual. The vestibular and lingual measurement of mandibular

molars are taken on the mesial roots. In the case of maxillary molars the buccal measure-

ments are taken on the mesiobuccal root. Obviously these measurements can only be

performed on teeth in situ.

To score defects in the interradicular region (furcation involvement), measurements are

taken by placing a periodontal probe (Hu-Friedy, Williams) buccally into the furcation

Figure 2. Scoring interalveolar defects.

SCORING DEFECTS OF THE ALVEOLAR PROCESS 115

(Figure 4). The probe must rest on the crestal bone and must be kept parallel to the

occlusal plane. The calibrations are read by looking along the buccal surface of the tooth,

so that both buccal roots can be seen in a direct line. The classification is as follows:

Figure 3. Scoring alveolar re-

sorption, vestibular measurement.

Q

I

1 :

1 I

\

\

I

I

\

\ I

\

,I .

\ \

\ \

3

Figure 4. Scoring furcation involvement.

appraximal view buccal view

0: no observable furcation.

1: entrance of possible furcation Q 1 mm accessible.

2: entrance of possible furcation >I mm accessible, but not passable.

3: open fur-cation, passable, one can see through it, or pass the probe through.

In case of classification 1 and 2 the possibility of a root fusion cannot be excluded.

Fenestration and dehiscence are quite similar types of defects.

The occurrence of both

appear to be influenced by the size and form of the alveolar process as well as the thickness

and curvature of the roots and their location in the dental arch.

116 D. MULLER AND W. R. K. PERIZONIUS

Afenestration is defined as a circumscribed perforation in the vestibular or lingual plate of

the alveolar process. If present, the size of the defect (length in millimeters, measured in

the longitudinal direction of the root) is recorded (Figure 5).

A dehiscenceis difficult to define clearly. It can be described as a defect in the vertical

direction from the alveolar crest of the bony covering of the root. It must be bordered

mesially and distally by alveolar bone in order to distinguish it from large interproximal

defects. To distinguish a dehiscence from shallow dips of the alveolar crest it was decided

that the length of the defect must be greater than the cervical width. This length is

defined as the distance from an imaginary continuous alveolar crest to the apex of the defect

and expressed in millimeters (Figure 5). Post-mortem loss of the teeth does not interfere

with the scoring of fenestration and dehiscence. Both defects are scored per alveolus and

on both the vestibular and the oral side.

Figure 5. Scoring fenestration (a)

and dehiscence (b).

The classifications of various defects of the alveolar process presented here are prefered

to those already in use. The classification of infrabony pockets (i.e. osseous defects

caused by periodontal disease) according to the number of osseous walls present (being

either three, two, or one, or a combination of these situations) as developed by Goldman &

Cohen (1958) and the classification of various types of infrabony pockets by Prichard

(1965), (craters, hemisepta, inconsistent margins), are designed for clinical use and seem

to be less applicable when used on skull material. It is felt that the scoring methods

presented here are more pertinent in the examination of skull material. An investigation

using these methods in order to determine periodontal destruction in samples of medieval

Dutch skulls is in progress.

Goldman, H. M. & Cohen, D. W. (1958). The hfrabony pocket: Classification and treatment. J omud of

Pmiodiwlblo~29,272-291.

Richard, J. (1965). Aa&anccd PniodonkJ LXseus#: Sur&al and Pro&& Mamgmcnt. Philadelphia and

London: W. B. Saunders.

Schectman, L. R, Ammona, W. F., Simpson, D. M. & Pqc, R. C. (1972).

periodontal diacase II. J oumd of Psridaull Rmmh 7, 195-212.

Host tissue raponrc in chronic

You might also like

- Jurnal Ilmu Konservasi Gigi: PSA Pada Supernumery RootDocument6 pagesJurnal Ilmu Konservasi Gigi: PSA Pada Supernumery RootAchmad Zam Zam AghazyNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Furcation-Involved TeethFrom EverandDiagnosis and Treatment of Furcation-Involved TeethLuigi NibaliNo ratings yet

- Oral Exostoses: An Assessment of Two Hundred Years of Research Les Exostoses Orales: Bilan de Deux Siècles de RecherchesDocument22 pagesOral Exostoses: An Assessment of Two Hundred Years of Research Les Exostoses Orales: Bilan de Deux Siècles de RecherchesYusuf DiansyahNo ratings yet

- Tumor Odontogenico EscamosoDocument4 pagesTumor Odontogenico Escamosoメカ バルカNo ratings yet

- The Radix Entomolaris in Mandibular First Molars: An Endodontic ChallengeDocument12 pagesThe Radix Entomolaris in Mandibular First Molars: An Endodontic Challengeratacha chingsuwanrojNo ratings yet

- Position of Teeth in Edentulous Maxilla DeterminedDocument6 pagesPosition of Teeth in Edentulous Maxilla DeterminedShafqat HussainNo ratings yet

- "Taurodontism" An Endodontic Challenge A Case ReportDocument4 pages"Taurodontism" An Endodontic Challenge A Case ReportDr.O.R.GANESAMURTHINo ratings yet

- dmf2SA Presentasi01Document5 pagesdmf2SA Presentasi01Iftinan LQNo ratings yet

- Annals of Anatomy: Reinhard E. Friedrich, Carsten Ulbricht, Ljuba A. Baronesse Von MaydellDocument12 pagesAnnals of Anatomy: Reinhard E. Friedrich, Carsten Ulbricht, Ljuba A. Baronesse Von MaydellVinay KumarNo ratings yet

- 4pulp Space MorphologyDocument68 pages4pulp Space Morphologyraghh roooNo ratings yet

- Ćosić2013Document6 pagesĆosić2013aida dzankovicNo ratings yet

- Odontogenic FibromaDocument5 pagesOdontogenic FibromaGowthamChandraSrungavarapuNo ratings yet

- Lateral Periodontal CystDocument8 pagesLateral Periodontal CystTejas KulkarniNo ratings yet

- ABGD Written Study Questions 2007Document291 pagesABGD Written Study Questions 2007velangni100% (1)

- Maxillary Lateral Incisor with Four Root CanalsDocument5 pagesMaxillary Lateral Incisor with Four Root Canalsdentace1No ratings yet

- Ge 2016Document9 pagesGe 2016Amani AouameurNo ratings yet

- Abstract-The Adverse Effects of Periodontal Disease On Dental Pulp Have Been Debated For ManyDocument11 pagesAbstract-The Adverse Effects of Periodontal Disease On Dental Pulp Have Been Debated For ManySri RahmawatiNo ratings yet

- Classification of Cleft Lip and Cleft PalateDocument14 pagesClassification of Cleft Lip and Cleft PalateRahul Kumar DiwakarNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 21 Ameloblastoma PeriferDocument3 pagesJurnal 21 Ameloblastoma PerifersriwahyuutamiNo ratings yet

- The Radix Entomolaris and Paramolaris: Clinical Approach in EndodonticsDocument6 pagesThe Radix Entomolaris and Paramolaris: Clinical Approach in EndodonticsPankajkumar GuptaNo ratings yet

- Missed Anatomy - Frequency and Clinical ImpactDocument29 pagesMissed Anatomy - Frequency and Clinical ImpactFerdi gamerNo ratings yet

- Maxillary First Molar Canal Configuration and Its Significance for Endodontic TherapyDocument7 pagesMaxillary First Molar Canal Configuration and Its Significance for Endodontic Therapyshamshuddin patelNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of Tonsilloliths and Other Oral and Maxillofacial Soft Tissue Calcifications On PanoramicDocument6 pagesThe Prevalence of Tonsilloliths and Other Oral and Maxillofacial Soft Tissue Calcifications On PanoramicInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- TMJ MorphologyDocument6 pagesTMJ MorphologyHossam BarghashNo ratings yet

- Diagnostico y Epidemiologia de Defectos OseosDocument14 pagesDiagnostico y Epidemiologia de Defectos OseosMariaNo ratings yet

- Calcifying Odontogenic Cyst and Denti - 2004 - Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery CLDocument7 pagesCalcifying Odontogenic Cyst and Denti - 2004 - Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery CLlaljadeff12No ratings yet

- A Method For Epidemiological Registration of MalocclusionDocument2 pagesA Method For Epidemiological Registration of Malocclusiontravolta0No ratings yet

- Large Cemento-Ossifying Fibroma of The Mandible Involving TheDocument4 pagesLarge Cemento-Ossifying Fibroma of The Mandible Involving TheDessy Dwi UtamiNo ratings yet

- Influence of Maxillary Posterior Discrepancy On Upper Molar Vertical Position and Facial Vertical Dimensions in Subjects With or Without Skeletal Open BiteDocument8 pagesInfluence of Maxillary Posterior Discrepancy On Upper Molar Vertical Position and Facial Vertical Dimensions in Subjects With or Without Skeletal Open BiteFlor GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- DA Vol 19 3Document36 pagesDA Vol 19 3Silvana Flores CastilloNo ratings yet

- Case ReportDocument4 pagesCase ReportAjeng Narita CaustinaNo ratings yet

- Erupted compound odontomas: A report of two casesDocument4 pagesErupted compound odontomas: A report of two casesmohamed ibrahimNo ratings yet

- 333 FullDocument6 pages333 FullImara BQNo ratings yet

- Paradental Cyst ArticleDocument6 pagesParadental Cyst Articlerohit singhaiNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Diagnosis of A Third Root Canal in First and Second Maxillary Premolars A Challenge For The ClinicianDocument7 pagesPreoperative Diagnosis of A Third Root Canal in First and Second Maxillary Premolars A Challenge For The ClinicianS S Saad SaadNo ratings yet

- Lobodontia Case Report: Unravelling the Wolf TeethDocument3 pagesLobodontia Case Report: Unravelling the Wolf TeethInas ManurungNo ratings yet

- Crim Medicine2013-407967Document3 pagesCrim Medicine2013-407967Greisy Saym Cruz FelixNo ratings yet

- Four Impacted Fourth Molars in A Young Patient: A Case ReportDocument5 pagesFour Impacted Fourth Molars in A Young Patient: A Case ReportPo PowNo ratings yet

- Impacted Maxillary Canines-A Review. - American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 101-159, 1992 PDFDocument13 pagesImpacted Maxillary Canines-A Review. - American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 101-159, 1992 PDFPia ContrerasNo ratings yet

- !!! Root Canal Morphology and It's Relationship To Endodontic Procedures - Frank J. Vertucci !!!Document27 pages!!! Root Canal Morphology and It's Relationship To Endodontic Procedures - Frank J. Vertucci !!!Puscas Madalina100% (1)

- Labiomandibular Paresthesia Caused by Endodontic Treatment - An Anatomic and Clinical Study PDFDocument13 pagesLabiomandibular Paresthesia Caused by Endodontic Treatment - An Anatomic and Clinical Study PDFAlexandra DumitracheNo ratings yet

- Bilateral Adenomatoid Odontogenic Tumour of The Maxilla in A 2-Year-Old Female-The Report of A Rare Case and Review of The LiteratureDocument7 pagesBilateral Adenomatoid Odontogenic Tumour of The Maxilla in A 2-Year-Old Female-The Report of A Rare Case and Review of The LiteratureStephanie LyonsNo ratings yet

- Palatal Rugae in Forensic Odontology - A ReviewDocument5 pagesPalatal Rugae in Forensic Odontology - A ReviewIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Plugin PtpmcrenderDocument3 pagesPlugin PtpmcrenderSaif SufyanNo ratings yet

- Shape and Volume of Craniofacial Cavities in Intentional Skull DeformationsDocument10 pagesShape and Volume of Craniofacial Cavities in Intentional Skull DeformationsGastón SalasNo ratings yet

- JDS 17 370Document15 pagesJDS 17 370Ferry HendrawanNo ratings yet

- !!! Missed Anatomy - Frequency and Clinical Impact !!!Document32 pages!!! Missed Anatomy - Frequency and Clinical Impact !!!Puscas MadalinaNo ratings yet

- Root Apex SumiDocument84 pagesRoot Apex SumiVinod S VinuNo ratings yet

- A Case of Enchondroma From Carolingian Necropolis of St. Pere de Terrassa (Spain) - An Insight Into The Archaeological Record Mcglynn2017Document5 pagesA Case of Enchondroma From Carolingian Necropolis of St. Pere de Terrassa (Spain) - An Insight Into The Archaeological Record Mcglynn2017Girafa ElefanteNo ratings yet

- Radix Entomolaris and Paramolaris: A Case Report of Mandibular First Molars with Three RootsDocument7 pagesRadix Entomolaris and Paramolaris: A Case Report of Mandibular First Molars with Three RootsRavi KanthNo ratings yet

- GargulioDocument8 pagesGargulioAnonymous vguBSSeGIDNo ratings yet

- Dens invaginatus classification and prevalenceDocument14 pagesDens invaginatus classification and prevalenceAndrew HuNo ratings yet

- E SpaceDocument6 pagesE SpaceNicolasFernandezNo ratings yet

- Dagenais 1992Document7 pagesDagenais 1992MarouaBOUFLIJANo ratings yet

- ABGD Written Study Questions 2007Document291 pagesABGD Written Study Questions 2007Almehey NaderNo ratings yet

- Knife-Edge Residual Ridges: A Clinical: Material and MethodsDocument4 pagesKnife-Edge Residual Ridges: A Clinical: Material and MethodsSyed Abdul BasitNo ratings yet

- Dehiscence and Fenestration in Skeletal Class I, II, and III Malocclusions Assessed With Cone-Beam Computed TomographyDocument8 pagesDehiscence and Fenestration in Skeletal Class I, II, and III Malocclusions Assessed With Cone-Beam Computed TomographysujeetNo ratings yet

- Ludwig AnginaDocument3 pagesLudwig AnginaWellyAnggaraniNo ratings yet

- 2013 14 8 Trigeminal Nerve Anatomy in Neuropathic and Non Neuropathic Orofacial Pain Patients 865 872Document8 pages2013 14 8 Trigeminal Nerve Anatomy in Neuropathic and Non Neuropathic Orofacial Pain Patients 865 872WellyAnggaraniNo ratings yet

- 02 Schwartz, Robbins Joe 2004Document13 pages02 Schwartz, Robbins Joe 2004anatomimanusiaNo ratings yet

- Bruxism and Premature Occlusal ContactsDocument6 pagesBruxism and Premature Occlusal ContactsWellyAnggarani100% (1)

- Dr. Azizah FKG - Nutrition in Infancy & ChildhoodDocument29 pagesDr. Azizah FKG - Nutrition in Infancy & ChildhoodWellyAnggaraniNo ratings yet

- SSCDocument5 pagesSSCWellyAnggaraniNo ratings yet

- ProsthodonticmanagementofendodonticallytreatedteethDocument35 pagesProsthodonticmanagementofendodonticallytreatedteethLisna K. RezkyNo ratings yet

- Two-Phase Treatment of Class II Malocclusion in Young Growing PatientDocument5 pagesTwo-Phase Treatment of Class II Malocclusion in Young Growing PatientWellyAnggaraniNo ratings yet

- Use of A Modified Anterior Inclined Plane in Dentoskleletas Class 2Document4 pagesUse of A Modified Anterior Inclined Plane in Dentoskleletas Class 2WellyAnggaraniNo ratings yet

- Use of A Modified Anterior Inclined Plane in Dentoskleletas Class 2Document4 pagesUse of A Modified Anterior Inclined Plane in Dentoskleletas Class 2WellyAnggaraniNo ratings yet

- Use of A Modified Anterior Inclined Plane in Dentoskleletas Class 2Document4 pagesUse of A Modified Anterior Inclined Plane in Dentoskleletas Class 2WellyAnggaraniNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Dental Structur Loss Procedure During Replacement AmalgamDocument5 pagesEvaluation of Dental Structur Loss Procedure During Replacement AmalgamWellyAnggaraniNo ratings yet

- Swelling and Tumor Mucosa Lesions Swelling and Tumor Mucosa LesionsDocument17 pagesSwelling and Tumor Mucosa Lesions Swelling and Tumor Mucosa LesionsWellyAnggaraniNo ratings yet

- Flap TechnicDocument8 pagesFlap TechnicWellyAnggaraniNo ratings yet

- Mechanisms and Control of Pathologic Bone Loss in PeriodontitisDocument15 pagesMechanisms and Control of Pathologic Bone Loss in PeriodontitisWellyAnggaraniNo ratings yet

- Types of Veneers in Dental WorldDocument6 pagesTypes of Veneers in Dental WorldLenutza LenutaNo ratings yet

- Brain Wave Vibration PDFDocument26 pagesBrain Wave Vibration PDFnikanor1100% (4)

- Questionsheet 1: Disease / Immunology A2.15Document6 pagesQuestionsheet 1: Disease / Immunology A2.15Nabindra RuwaliNo ratings yet

- 365 STRONG Eat Like A BodybuilderDocument10 pages365 STRONG Eat Like A BodybuilderSlevin_KNo ratings yet

- DietPlan14DayLowCarbPrimalKeto 5Document131 pagesDietPlan14DayLowCarbPrimalKeto 5josuedsneto100% (5)

- Rupert Pupkin: Narcissistic Personality DisorderDocument3 pagesRupert Pupkin: Narcissistic Personality DisorderShreya MahourNo ratings yet

- Diabetic Foot Wound OffloadingDocument8 pagesDiabetic Foot Wound OffloadingTBNo ratings yet

- Rifaximin For The Treatment of TDDocument11 pagesRifaximin For The Treatment of TDAnkur AgrawalNo ratings yet

- CvadDocument11 pagesCvadNjideka A.No ratings yet

- Tetracycline Drug Reporting-2Document21 pagesTetracycline Drug Reporting-2Shynne RPhNo ratings yet

- Exercises For Diastasis Recti - Rehabilitative Workout FromDocument2 pagesExercises For Diastasis Recti - Rehabilitative Workout Fromjmbeckstrand83% (6)

- Integrated Management of Childhood IllnessDocument2 pagesIntegrated Management of Childhood Illness지창욱No ratings yet

- Algoritma Penanganan Kejang AkutDocument1 pageAlgoritma Penanganan Kejang AkutEwa ClaudiaNo ratings yet

- Dialysis PowerpointDocument10 pagesDialysis Powerpointapi-266328774No ratings yet

- CCO Myeloma Nursing TU13 SlidesDocument47 pagesCCO Myeloma Nursing TU13 SlidesLaura TololoiNo ratings yet

- Opthalmology Visuals New PDF-1Document100 pagesOpthalmology Visuals New PDF-1singh0% (1)

- The Top 70 Microbiology RegulationsDocument3 pagesThe Top 70 Microbiology RegulationsRudra RahmanNo ratings yet

- Interpreting and Implementing The 2018 Pain, Agitation:Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption Clinical Practice Guideline - Balas2018Document7 pagesInterpreting and Implementing The 2018 Pain, Agitation:Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption Clinical Practice Guideline - Balas2018RodrigoSachiFreitasNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research InterviewsDocument8 pagesQualitative Research InterviewsDaniel Fancis Amabran BarrientosNo ratings yet

- Research Paper: Coaching and Counseling - What Can We Learn From Each Other?Document11 pagesResearch Paper: Coaching and Counseling - What Can We Learn From Each Other?International Coach AcademyNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Palsy in ChildrenDocument17 pagesCerebral Palsy in Childrenapi-320401765No ratings yet

- International Journal of Pharmaceutics: Shuai Qian, Yin Cheong Wong, Zhong ZuoDocument11 pagesInternational Journal of Pharmaceutics: Shuai Qian, Yin Cheong Wong, Zhong ZuomoazrilNo ratings yet

- Risperdal ConstaDocument32 pagesRisperdal ConstammoslemNo ratings yet

- Cure For All DiseasesDocument4 pagesCure For All DiseasesNiquezNo ratings yet

- Debridement PDFDocument4 pagesDebridement PDFWahyu IndraNo ratings yet

- Working in The Heat & Cold in AlbertaDocument96 pagesWorking in The Heat & Cold in Albertacanadiangrizzer1100% (1)

- Anaesthesiology Faculty and Trainees at Medical CollegeDocument9 pagesAnaesthesiology Faculty and Trainees at Medical CollegeSubhadeep SarkarNo ratings yet

- Belazo Alkali Sealer MSDSDocument4 pagesBelazo Alkali Sealer MSDSrumahsketchNo ratings yet

- High End Dental and Facial Aesthetics Design Feasability and Research DocumentDocument115 pagesHigh End Dental and Facial Aesthetics Design Feasability and Research DocumentNatalie JamesonNo ratings yet

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (402)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo ratings yet

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (78)

- Techniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementFrom EverandTechniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (40)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (169)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- The Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesFrom EverandThe Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (34)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (327)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsFrom EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNo ratings yet

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeFrom EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (253)

- The Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingFrom EverandThe Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (41)

- The Stress-Proof Brain: Master Your Emotional Response to Stress Using Mindfulness and NeuroplasticityFrom EverandThe Stress-Proof Brain: Master Your Emotional Response to Stress Using Mindfulness and NeuroplasticityRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (109)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (33)

- The Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossFrom EverandThe Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (8)