Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Prieto - State's Brief

Uploaded by

Chris GeidnerCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Prieto - State's Brief

Uploaded by

Chris GeidnerCopyright:

Available Formats

Nos.

13-8021, 14-6226

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

ALFREDO PRIETO,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

v.

HAROLD C. CLARKE, Director; A. DAVID ROBINSON, Deputy Director; E.

PEARSON, Warden,

Defendants-Appellants.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA (Hon. Leonie M. Brinkema) (1:12-cv-1199)

OPENING BRIEF OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS

MARK R. HERRING

Attorney General of Virginia

CYNTHIA E. HUDSON

Chief Deputy Attorney General

LINDA L. BRYANT (VSB #35010)

Deputy Attorney General,

Public Safety & Enforcement

RICHARD C. VORHIS (VSB #23170)

Senior Assistant Attorney General

rvorhis@oag.state.va.us

KATE E. DWYRE (VSB #82065)

Assistant Attorney General

kdwyre@oag.state.va.us

STUART A. RAPHAEL (VSB #30380)

Solicitor General of Virginia

sraphael@oag.state.va.us

TREVOR S. COX (VSB #78396)

Deputy Solicitor General

tcox@oag.state.va.us

Office of the Attorney General

900 East Main Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

(804) 786-7240 Telephone

(804) 371-0200 Facsimile

Counsel for Appellants

March 24, 2014

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 1 of 77

10/28/2013 SCC - 1 -

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

DISCLOSURE OF CORPORATE AFFILIATIONS AND OTHER INTERESTS

Disclosures must be filed on behalf of all parties to a civil, agency, bankruptcy or mandamus

case, except that a disclosure statement is not required from the United States, from an indigent

party, or from a state or local government in a pro se case. In mandamus cases arising from a

civil or bankruptcy action, all parties to the action in the district court are considered parties to

the mandamus case.

Corporate defendants in a criminal or post-conviction case and corporate amici curiae are

required to file disclosure statements.

If counsel is not a registered ECF filer and does not intend to file documents other than the

required disclosure statement, counsel may file the disclosure statement in paper rather than

electronic form. Counsel has a continuing duty to update this information.

No. __________ Caption: __________________________________________________

Pursuant to FRAP 26.1 and Local Rule 26.1,

______________________________________________________________________________

(name of party/amicus)

______________________________________________________________________________

who is _______________________, makes the following disclosure:

(appellant/appellee/petitioner/respondent/amicus/intervenor)

1. Is party/amicus a publicly held corporation or other publicly held entity? YES NO

2. Does party/amicus have any parent corporations? YES NO

If yes, identify all parent corporations, including grandparent and great-grandparent

corporations:

3. Is 10% or more of the stock of a party/amicus owned by a publicly held corporation or

other publicly held entity? YES NO

If yes, identify all such owners:

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 9 Filed: 12/30/2013 Pg: 1 of 2

13-8021 Alfredo Prieto v. Harold Clarke, et al.

Harold Clarke

Appellant

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 2 of 77

- 2 -

4. Is there any other publicly held corporation or other publicly held entity that has a direct

financial interest in the outcome of the litigation (Local Rule 26.1(b))? YES NO

If yes, identify entity and nature of interest:

5. Is party a trade association? (amici curiae do not complete this question) YES NO

If yes, identify any publicly held member whose stock or equity value could be affected

substantially by the outcome of the proceeding or whose claims the trade association is

pursuing in a representative capacity, or state that there is no such member:

6. Does this case arise out of a bankruptcy proceeding? YES NO

If yes, identify any trustee and the members of any creditors committee:

Signature: ____________________________________ Date: ___________________

Counsel for: __________________________________

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

**************************

I certify that on _________________ the foregoing document was served on all parties or their

counsel of record through the CM/ECF system if they are registered users or, if they are not, by

serving a true and correct copy at the addresses listed below:

_______________________________ ________________________

(signature) (date)

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 9 Filed: 12/30/2013 Pg: 2 of 2

s/Kate E. Dwyre 12/30/2013

Harold Clarke

12/30/2013

Katherine M. Gigliotti, Esquire

Michael E. Bern, Esquire

Daniel I. Levy, Esquire

Lantham&Watkins, LLP

555 Eleventh Street, NW, Suite 1000

Washington, DC 20004-1304

E-mail: katherine.gigliotti@lw.com

s/Kate E. Dwyre 12/30/2013

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 3 of 77

10/28/2013 SCC - 1 -

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

DISCLOSURE OF CORPORATE AFFILIATIONS AND OTHER INTERESTS

Disclosures must be filed on behalf of all parties to a civil, agency, bankruptcy or mandamus

case, except that a disclosure statement is not required from the United States, from an indigent

party, or from a state or local government in a pro se case. In mandamus cases arising from a

civil or bankruptcy action, all parties to the action in the district court are considered parties to

the mandamus case.

Corporate defendants in a criminal or post-conviction case and corporate amici curiae are

required to file disclosure statements.

If counsel is not a registered ECF filer and does not intend to file documents other than the

required disclosure statement, counsel may file the disclosure statement in paper rather than

electronic form. Counsel has a continuing duty to update this information.

No. __________ Caption: __________________________________________________

Pursuant to FRAP 26.1 and Local Rule 26.1,

______________________________________________________________________________

(name of party/amicus)

______________________________________________________________________________

who is _______________________, makes the following disclosure:

(appellant/appellee/petitioner/respondent/amicus/intervenor)

1. Is party/amicus a publicly held corporation or other publicly held entity? YES NO

2. Does party/amicus have any parent corporations? YES NO

If yes, identify all parent corporations, including grandparent and great-grandparent

corporations:

3. Is 10% or more of the stock of a party/amicus owned by a publicly held corporation or

other publicly held entity? YES NO

If yes, identify all such owners:

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 10 Filed: 12/30/2013 Pg: 1 of 2

13-8021 Alfredo Prieto v. Harold Clarke, et al.

A. David Robinson

Appellant

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 4 of 77

- 2 -

4. Is there any other publicly held corporation or other publicly held entity that has a direct

financial interest in the outcome of the litigation (Local Rule 26.1(b))? YES NO

If yes, identify entity and nature of interest:

5. Is party a trade association? (amici curiae do not complete this question) YES NO

If yes, identify any publicly held member whose stock or equity value could be affected

substantially by the outcome of the proceeding or whose claims the trade association is

pursuing in a representative capacity, or state that there is no such member:

6. Does this case arise out of a bankruptcy proceeding? YES NO

If yes, identify any trustee and the members of any creditors committee:

Signature: ____________________________________ Date: ___________________

Counsel for: __________________________________

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

**************************

I certify that on _________________ the foregoing document was served on all parties or their

counsel of record through the CM/ECF system if they are registered users or, if they are not, by

serving a true and correct copy at the addresses listed below:

_______________________________ ________________________

(signature) (date)

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 10 Filed: 12/30/2013 Pg: 2 of 2

s/Kate E. Dwyre 12/30/2013

A. David Robinson

12/30/2013

Katherine M. Gigliotti, Esquire

Michael E. Bern, Esquire

Daniel I. Levy, Esquire

Lantham&Watkins, LLP

555 Eleventh Street, NW, Suite 1000

Washington, DC 20004-1304

E-mail: katherine.gigliotti@lw.com

s/Kate E. Dwyre 12/30/2013

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 5 of 77

10/28/2013 SCC - 1 -

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

DISCLOSURE OF CORPORATE AFFILIATIONS AND OTHER INTERESTS

Disclosures must be filed on behalf of all parties to a civil, agency, bankruptcy or mandamus

case, except that a disclosure statement is not required from the United States, from an indigent

party, or from a state or local government in a pro se case. In mandamus cases arising from a

civil or bankruptcy action, all parties to the action in the district court are considered parties to

the mandamus case.

Corporate defendants in a criminal or post-conviction case and corporate amici curiae are

required to file disclosure statements.

If counsel is not a registered ECF filer and does not intend to file documents other than the

required disclosure statement, counsel may file the disclosure statement in paper rather than

electronic form. Counsel has a continuing duty to update this information.

No. __________ Caption: __________________________________________________

Pursuant to FRAP 26.1 and Local Rule 26.1,

______________________________________________________________________________

(name of party/amicus)

______________________________________________________________________________

who is _______________________, makes the following disclosure:

(appellant/appellee/petitioner/respondent/amicus/intervenor)

1. Is party/amicus a publicly held corporation or other publicly held entity? YES NO

2. Does party/amicus have any parent corporations? YES NO

If yes, identify all parent corporations, including grandparent and great-grandparent

corporations:

3. Is 10% or more of the stock of a party/amicus owned by a publicly held corporation or

other publicly held entity? YES NO

If yes, identify all such owners:

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 11 Filed: 12/30/2013 Pg: 1 of 2

13-8021 Alfredo Prieto v. Harold Clarke, et al.

E. Pearson

Appellant

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 6 of 77

- 2 -

4. Is there any other publicly held corporation or other publicly held entity that has a direct

financial interest in the outcome of the litigation (Local Rule 26.1(b))? YES NO

If yes, identify entity and nature of interest:

5. Is party a trade association? (amici curiae do not complete this question) YES NO

If yes, identify any publicly held member whose stock or equity value could be affected

substantially by the outcome of the proceeding or whose claims the trade association is

pursuing in a representative capacity, or state that there is no such member:

6. Does this case arise out of a bankruptcy proceeding? YES NO

If yes, identify any trustee and the members of any creditors committee:

Signature: ____________________________________ Date: ___________________

Counsel for: __________________________________

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

**************************

I certify that on _________________ the foregoing document was served on all parties or their

counsel of record through the CM/ECF system if they are registered users or, if they are not, by

serving a true and correct copy at the addresses listed below:

_______________________________ ________________________

(signature) (date)

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 11 Filed: 12/30/2013 Pg: 2 of 2

s/Kate E. Dwyre 12/30/2013

E. Pearson

12/30/2013

Katherine M. Gigliotti, Esquire

Michael E. Bern, Esquire

Daniel I. Levy, Esquire

Lantham&Watkins, LLP

555 Eleventh Street, NW, Suite 1000

Washington, DC 20004-1304

E-mail: katherine.gigliotti@lw.com

s/Kate E. Dwyre 12/30/2013

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 7 of 77

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENTS ...................................................... ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................... iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................................................................... vi

J URISDICTIONAL STATEMENT .......................................................................... 1

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW ..................................................................... 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .................................................................................. 3

STATEMENT OF FACTS ........................................................................................ 8

A. Prietos crimes, trials, and convictions. ................................................ 8

B. Virginias other offenders currently on death row. .............................11

C. The professional judgment of Virginias prison officials about the

importance of segregating death-row offenders. .................................14

D. Virginias prison-housing policies. .....................................................16

E. Prietos complaints about conditions on death row. ...........................20

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ...............................................................................27

ARGUMENT ...........................................................................................................31

I. The Supreme Court and Fourth Circuit have repeatedly emphasized

the substantial deference owed to prison officials judgments

concerning conditions of confinement. ......................................................... 31

II. Prieto has no State-law liberty interest in being considered for

placement in the general prison population that entitles him to any

protection under the Due Process Clause. ..................................................... 35

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 8 of 77

iv

A. State law, not federal law, determines if prisoners enjoy a liberty

interest in avoiding prison conditions that, as in this case, do not

otherwise violate the Constitution. ......................................................36

1. Wolff and Meachum. ................................................................. 36

2. Greenholtz through Hewitt. ....................................................... 38

3. Sandin establishes a second barrier to State-law liberty

claims: the condition must impose atypical and

significant hardship compared to the relevant prisoner

baseline. ..................................................................................... 39

4. The Supreme Court has not yet instructed lower courts

how to determine the relevant baseline for deciding when

a prisoner is exposed to atypical hardship. ............................ 41

5. Lower courts have regularly applied Sandins twin

barriers to recognizing State-created liberty interests. ............. 43

B. Each of Sandins barriers independently requires judgment for

Virginia in this case. ............................................................................45

1. Virginia law creates no reasonable expectation that

capital offenders will be housed anyplace other than

death row. .................................................................................. 46

2. Because death row is sui generis, the relevant baseline

for comparison is death-row housing, not general

prisoner housing. ....................................................................... 47

C. Prieto ignored the requirement to ground the liberty interest in State

law. ......................................................................................................50

D. Even if it were legally relevant to compare Virginias death row to

death row in other States, Virginias segregation of death-row inmates

is not unique. .......................................................................................52

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 9 of 77

v

III. The District Court improperly second-guessed the professional

judgment of Virginias prison officials that death-row offenders are

too dangerous to house in the general prison population. ............................. 54

IV. The injunction is invalid because it violates Federal Rule 65 and the

Prison Litigation Reform Act. ....................................................................... 56

V. The Court should also vacate the award of attorneys fees and costs. .......... 58

CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................58

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENET ...........................................60

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE .......................................................................60

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ....................................................................................

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 10 of 77

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

CASES

Apanovitch v. Wilkinson,

32 F. Appx 704 (6th Cir. 2002) ..........................................................................50

Austin v. Wilkinson,

No. 4:01-cv-71, 2008 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 24032 (N.D. Ohio Mar.

11, 2008) ..............................................................................................................49

Beard v. Banks,

548 U.S. 521 (2006) ...................................................................................... 34, 35

Bell v. Wolfish,

441 U.S. 520 (1979) .............................................................................................33

Beverati v. Smith,

120 F.3d 500 (4th Cir. 1997)..................................................................... 4, 28, 47

Braun v. Maynard,

652 F.3d 557 (4th Cir. 2011)......................................................................... 32, 56

Brown v. McGinnis,

No. 05-cv-758S, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 10847 (W.D.N.Y. J an.

20, 2012) ..............................................................................................................44

Burns v. Virginia,

261 Va. 307, 541 S.E.2d 872,

cert. denied, 534 U.S. 1043 (2001) ......................................................................12

Cagle v. Hutto,

177 F.3d 253 (4th Cir. 1999)......................................................................... 57, 58

Conway v. Wilkinson,

No. 2:05-cv-820, 2005 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 31294 (S.D. Ohio Dec.

6, 2005) ......................................................................................................... 49, 56

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 11 of 77

vii

Filarsky v. Delia,

132 S. Ct. 1657 (2012) .........................................................................................46

Florence v. Bd. of Chosen Freeholders,

132 S. Ct. 1510 (2012) ...................................................................... 32, 33, 34, 35

Frazier v. Coughlin,

81 F.3d 313 (2d Cir. 1996) ...................................................................... 43, 44, 45

Gaston v. Taylor,

946 F.2d 340 (4th Cir. 1991)................................................................................33

Gray v. Virginia,

274 Va. 290, 645 S.E.2d 448 (2007),

cert. denied, 552 U.S. 1151 (2008) ......................................................................11

Green v. Venable,

No. 3:09-cv-154, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 85928 (E.D. Va. Aug.

10, 2010) ..............................................................................................................44

Greenholtz v. Nebraska Penal Inmates,

442 U.S. 1 (1979) .......................................................................................... 38, 39

Guilbert v. Sennet,

235 F. Appx, 823 (2d Cir. 2007) ........................................................................44

Hewitt v. Helms,

459 U.S. 460 (1983) ................................................................................ 39, 40, 43

Hill v. Lockheed Martin Logistics Mgmt., Inc.,

354 F.3d 277 (4th Cir. 2004)................................................................................31

Hudson v. Palmer,

468 U.S. 517 (1984) ...................................................................................... 32, 35

Juniper v. Virginia,

271 Va. 362, 626 S.E.2d 383,

cert. denied, 549 U.S. 960 (2006) ........................................................................12

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 12 of 77

viii

Lawlor v. Virginia,

285 Va. 187, 209, 738 S.E.2d 847,

cert. denied, 134 S. Ct. 427 (2013) ......................................................................12

Lee v. Gurney,

No. 3:08-cv-130493, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 130493 (E.D. Va.

Dec. 9, 2010) ........................................................................................................44

Lisle v. McDaniel,

No. 3:10-cv-00064, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 170471 (D. Nev. J uly

5, 2012), adopted by 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 170467 (D. Nev.

Nov. 30, 2012) ......................................................................................................49

Lolavar v. de Santibanes,

430 F.3d 221 (4th Cir. 2005)................................................................................45

Mathews v. Eldridge,

424 U.S. 319 (1976) .............................................................................................39

McKune v. Lile,

536 U.S. 24 (2002) ...............................................................................................34

Meachum v. Fano,

427 U.S. 215 (1976) .............................................................. 36, 37, 38, 46, 50, 51

Morva v. Virginia,

278 Va. 329, 683 S.E.2d 553 (2009),

cert. denied, 131 S. Ct. 97 (2010) ................................................................. 12, 13

Olim v. Wakinekona,

461 U.S. 238 (1983) .............................................................................................39

Overton v. Bazetta,

539 U.S. 126 (2003) ................................................................................ 32, 34, 35

Parker v. Cook,

642 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1981)................................................................................50

Pearson v. Callahan,

555 U.S. 223 (2009) .............................................................................................45

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 13 of 77

ix

Pell v. Procunier,

417 U.S. 817 (1974) .............................................................................................35

Peterkin v. Jeffes,

855 F.2d 1021 (3rd Cir. 1988) .............................................................................50

Porter v. Virginia,

276 Va. 203, 661 S.E.2d 415 (2008),

cert. denied, 556 U.S. 1189 (2009) ......................................................................13

Prieto v. Clarke,

No. 1:12-cv-1199, 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 161783 (E.D. Va. Nov.

12, 2013) ...................................................................................................... passim

Prieto v. Davis,

No. 3:13-cv-849 (E.D. Va. 2014) ........................................................................11

Prieto v. Virginia,

133 S. Ct. 244 (2012) ...........................................................................................10

Prieto v. Virginia,

278 Va. 366, 682 S.E.2d 910 (2009) ..................................................... 8, 9, 10, 55

Prieto v. Virginia,

283 Va. 149, 721 S.E.2d 484,

cert. denied, 133 S. Ct. 244 (2012) ............................................................... 10, 55

Prieto v. Warden of the Sussex I State Prison,

286 Va. 99, 748 S.E.2d 94 (2013) ........................................................................10

Puranda v. Hill,

No. 3:10-cv-733, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 84238 (E.D. Va. 2012) ......................44

Puranda v. Johnson,

No. 3:08-cv-00687, 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 93226 (E.D. Va. Sept.

30, 2009), appeal dismissed, 367 F. Appx 453 (4th Cir. 2010) ............ 44, 45, 51

Rossignol v. Voorhaar,

316 F.3d 516 (4th Cir. 2003)................................................................................31

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 14 of 77

x

Sandin v. Conner,

515 U.S. 472 (1995) ..................................................................................... passim

Schaffer v. Weast,

554 F.3d 470 (4th Cir. 2009)................................................................................58

Smith v. Coughlin,

748 F.2d 783 (2nd Cir. 1984) ...............................................................................50

Teleguz v. Virginia,

273 Va. 458, 643 S.E.2d 708 (2007),

cert. denied, 552 U.S. 1191 (2008) ......................................................................13

Thornburg v. Abbott,

490 U.S. 401 (1989) .............................................................................................35

Turner v. Safley,

482 U.S. 78 (1987) .................................................................................. 32, 33, 34

VCA Cenvet, Inc. v. Chadwell Animal Hosp., LLC,

No. 13-1369, 2014 U.S. App. LEXIS 869 (4th Cir. J an. 16, 2014).....................31

Vitek v. Jones,

445 U.S. 480 (1980) .............................................................................................38

Wilkinson v. Austin,

545 U.S. 209 (2005) .................................................... 6, 28, 42, 45, 47, 49, 51, 52

Williams v. Wetzel,

No. 12-944, 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 184000 (W.D. Pa. Dec. 9, 2013),

adopted by 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 7428 (W.D. Pa. J an. 22, 2014). ...................48

Wolff v. McDonnell,

418 U.S. 539 (1974) .............................................................. 36, 38, 41, 46, 50, 51

STATUTES

18 U.S.C. 3626(a)(1)(A) ................................................................................ 30, 57

18 U.S.C. 3626(a)(1)(B) ................................................................................ 30, 57

18 U.S.C. 3626(b)(2)...................................................................................... 30, 57

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 15 of 77

xi

28 U.S.C. 1331 ........................................................................................................ 1

28 U.S.C. 1915A ..................................................................................................... 3

42 U.S.C. 1983 ....................................................................................... 1, 3, 46, 48

2013 Md. Acts ch. 156 .............................................................................................53

Va. Code Ann. 19.2-264.2 (2009) ........................................................................55

1965 W. Va. Acts ch. 40,

codified at W. Va. Code Ann. 61-11-2 (2013) ..................................................53

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

U.S. Const. amend VIII ............................................................................. 3, 4, 34, 35

U.S. Const. amend. XIV ....................................................... 3, 35, 36, 37, 39, 41, 52

RULES

Fed. R. App. P. 4(a)(5) ...........................................................................................1, 7

Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(d) ......................................................................................... 30, 56

REGULATIONS

Va. Dept of Corrections, Operating Procedure 460.A .............................. 17, 46, 57

Va. Dept of Corrections, Operating Procedure 830.2 ......................... 17, 19, 46, 57

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Bryan A. Garner, Garners Dictionary of Legal Usage (3d ed. 2011) ...................... 8

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 16 of 77

1

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

The District Court had jurisdiction, under 28 U.S.C. 1331, over this

prisoner civil rights claim brought by a death-row inmate pursuant to 42 U.S.C.

1983. The District Court entered an order on November 12, 2013, enjoining

Defendants either to provide him with an individualized classification

determination for his prison housing, using procedures that are the same or

substantially similar to the procedures used for all non-capital offenders, or to

improve his conditions of confinement so they do not impose an atypical and

significant hardship. (J A 850-51.) Appellants timely noted their appeal from that

Order on December 9, 2013 (docketed December 12, 2013). (J A 857.) On

J anuary 10, 2014, the District Court denied Defendants motion to stay the

injunction pending appeal. (J A 897.)

The District Court entered a separate order awarding attorneys fees and

costs to plaintiff on December 13, 2013. (J A 858.) On J anuary 27, 2014,

Appellants filed a motion with the District Court, within the time allowed under

Fed. R. App. P. 4(a)(5), to extend the time to note a separate appeal from that

award. (J A 13.) On February 4, 2014, the District Court entered an order stating

that it did not believe that defendants need to file a second Notice of Appeal to

contest the award of attorneys fees and costs to plaintiff because that award is part

of the final judgment of the Court, but the District Court nevertheless granted

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 17 of 77

2

their motion, finding good cause to extend the time to appeal it. (J A 899.)

Appellants timely noted the appeal on February 6, 2014. (J A 901.)

This Court consolidated the two appeals on February 20, 2014. (Doc. 20.)

The Court has appellate jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. 1291.

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

Under Sandin v. Conner, courts evaluate due process challenges to prison

conditions by asking if the State imposes atypical and significant hardship on the

inmate in relation to the ordinary incidents of prison life, and by determining if

State law has created a liberty interest with regard to the entitlement claimed.

515 U.S. 472, 484 (1995). Neither the Supreme Court nor this Court has applied

Sandin in the context of death-row inmates.

Virginia houses its capital offenders in highly secure, segregated

confinement on death row. Non-death-row prisoners, by contrast, are assigned to

prisons with varying security levels based on a series of individualized factors.

The District Court ordered Virginias prison officials to apply the same or similar

system of individualized factors to Plaintiff, a death-row inmate, or to improve his

current conditions of confinement so they do not impose an atypical and

significant hardship.

The questions presented are whether the baseline for determining if death-

row confinement is atypical under Sandin is the death-row population or the

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 18 of 77

3

general prison population, and whether Virginia has created a valid liberty

interest on the part of death-row inmates to be considered for housing in the

general prison population.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On October 24, 2012, Plaintiff Alfredo Prieto brought a pro se prisoner civil

rights claim against Virginias prison officials under 42 U.S.C. 1983. (J A 2, 14.)

He claimed that the conditions of his solitary confinement on death row constituted

cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment, and that the

refusal of prison officials to allow him privileges enjoyed by inmates in the general

prison population, and to consider him for housing there, violated the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. (J A 18-20.)

Screening his claim under 28 U.S.C. 1915A, the District Court, the Hon.

Leonie M. Brinkema presiding, dismissed Prietos Eighth Amendment claim but

concluded that Prieto had stated a claim that his due process rights have been

violated by his indefinite placement in a special housing unit. (J A 179.)

On November 27, 2012, Prieto appealed the District Courts dismissal of his

Eighth Amendment claim. (J A 186.)

On December 10, 2012, pro bono defense counsel entered an appearance for

Prieto in the District Court. (J A 3.)

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 19 of 77

4

On J anuary 25, 2013, defendant prison officials, represented by the Office of

the Attorney General of Virginia, filed an answer and motion for summary

judgment. (J A 188, 193.)

On February 6, 2013, this Court dismissed Prietos appeal of his Eighth

Amendment claim for failure to prosecute it. (J A 202, 828.)

As for the due process claims remaining in the District Court, Prietos new

counsel argued that summary judgment was premature because discovery was

needed. The District Court agreed, denying Defendants motion without prejudice;

extensive discovery ensued. (J A 828.)

At the close of discovery, Defendants renewed their summary judgment

motion and Prieto cross-moved for summary judgment. (J A 9.) The District Court

heard oral argument on September 6, 2013. (J A 785.)

On November 12, 2013, the District Court issued a memorandum opinion

granting summary judgment to Prieto and denying it to Defendants. Prieto v.

Clarke, No. 1:12-cv-1199, 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 161783 (E.D. Va. Nov. 12,

2013) (J A 822). The District Court concluded that, under this Courts decision in

Beverati v. Smith, 120 F.3d 500, 504 (4th Cir. 1997), the relevant baseline for

comparing prison conditions on death row were the conditions in the general

prison population at Sussex I State Prison. 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 161783, at *14

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 20 of 77

5

(J A 834). The opinion did not address whether Virginia law created a liberty

interest on the part of death-row offenders to avoid segregated confinement.

Comparing conditions to the general population, the District Court

concluded that the conditions on death row are uniquely severe, and that death

row inmates like plaintiff are denied all freedom of movement and most freedom to

interact with others. There can be no dispute that almost every aspect of a death

row inmates life is controlled and monitored. Id. at *17 (J A 836-37). The

court [found] it significant that plaintiff has already spent five years in this

placement, and there is no end in sight. Plaintiff has not even begun federal post-

conviction proceedings, which are likely to play out over the course of several

years and further delay the carrying out of his sentence. (J A 837.)

The District Court further found that the nature of plaintiffs confinement

furthers few, if any, legitimate penological goals, such as those that might justify

solitary confinement temporarily for valid punitive, protective, or investigative

purposes. Id. at *21 (J A 840). The court concluded that Prieto has been by all

accounts a model prisoner and had not engaged in any of the behaviors that

would normally support placement in segregated confinement. Id.

The District Court enjoined Virginia to:

provide plaintiff with an individualized classification

determination using procedures that are the same or

substantially similar to the procedures used for all non-

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 21 of 77

6

capital offenders, and/or that defendants improve

plaintiffs conditions of confinement such that the

confinement does not impose an atypical and significant

hardship. (J A 850-51.)

The courts opinion described that injunction as limited and identified two

ways that Virginia officials could comply:

First, defendants could provide plaintiff with an

individualized classification determination using

procedures that are the same or substantially similar to

the procedures used for all non-capital offenders, as

plaintiff requests. Doing so would likely comport with

the minimal due process requirements described in

Wilkinson [v. Austin, 545 U.S. 209, 226-27 (2005)].

Second, defendants could vary the basic conditions of

confinement on death row, if only slightly, such that

confinement there would no longer impose an atypical

and significant hardship on plaintiff. Id. at *30-31 (J A

848).

As to its second suggestion, the court did not specify which of Prietos many

complaints about the conditions of his confinement would have to be addressed so

that his confinement was no longer atypical compared to conditions in the

general prison population at Sussex I State Prison.

On November 25, 2013, Prieto moved for attorneys fees of $151,734.39 and

costs of $13,661.60. (J A 853). Defendants did not dispute the amounts claimed in

the event the underlying judgment were affirmed on appeal. (J A 855.)

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 22 of 77

7

On December 9, 2013, Defendants appealed the judgment (although the

appeal was not docketed until December 12, within the 30 days allowed). (J A

857.)

On December 13, 2013, the court awarded Prieto attorneys fees and costs in

the amount he requested. (J A 858.)

On December 20, 2013, Defendants moved to stay the injunction pending

appeal. (J A 12.) They explained at the hearing on J anuary 10, 2014, that in order

to do a meaningful classification of Mr. Prieto, [Virginia officials] would have to

change the classification system as it is now because it does not currently

contemplate a death sentence as it does life sentences; [i]ts asking the

Department to radically change how theyre housing death-sentenced inmates.

(J A 893.) The court responded that the majority of the states within the Fourth

Circuit, in fact, do house their death row inmates differently than does Virginia

(J A 892), that conditions on Virginias death row are inhumane (J A 894), and

that Prieto was entitled to the otherwise rational classification system Virginia

uses for its non-death-row prisoners (J A 895). So the Court denied the motion to

stay the injunction pending appeal. (J A 897.)

On February 4, 2014, the Court granted Defendants motion under Fed. R.

App. P. 4(a)(5) to extend the time to note an appeal from the December 13, 2013

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 23 of 77

8

Order awarding attorneys fees and costs (J A 899), and Defendants noted that

appeal on February 6, 2014 (J A 901). The appeals have been consolidated here.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Since October 30, 2008, Prieto has been confined in a special housing unit at

Sussex I State Prison, awaiting the imposition of the death penalty for two

convictions of capital murder. (J A 195, 203, 435.) The unit is commonly

referred to as death row. (J A 435). The phrase death row is used throughout

the United States; it is an Americanism dating from the early 1940s . . . . Bryan

A. Garner, Garners Dictionary of Legal Usage 248 (3d ed. 2011).

A. Prietos crimes, trials, and convictions.

Rachael A. Raver and Warren H. Fulton, III, both 22, were last seen alive

leaving a restaurant together, after midnight on December 4, 1988. Prieto v.

Virginia, 278 Va. 366, 377, 682 S.E.2d 910, 915 (2009) (Prieto I). Two days later,

Ravers partially nude body was found lying in a field . . . in Fairfax County.

Fultons fully clothed body was found about 100 feet away from Ravers body.

Ravers jeans, underpants, gloves, and shoes were found approximately halfway

between the two bodies. Id. Raver received a single gunshot wound to the back

and had scraping of the skin on her abdomen, legs, hands, and face, and a bruise

on her neck, caused by the pushing or pulling of her body . . . . Id. at 378, 682

S.E.2d at 915. Her body was found undressed from the waist down with her legs

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 24 of 77

9

spread apart on the ground . . . . Id. Biological residues from her thighs and

vagina were collected and preserved. Id. Fulton was killed by a single gunshot,

also into his back. Id. Although investigators attempted in early 1989 to identify a

suspect, there was no match at that time to the DNA evidence found on Ravers

body. Id. at 379, 682 S.E.2d at 915-16.

In September 2005, almost 17 years after the murders, DNA testing

connected Prieto to the crimes. Id. at 379-80, 682 S.E.2d at 916. Prieto was then

being held on death row in California for the rape and murder of a 15-year-old girl

who, like Raver, was found in a remote, open field, partially unclothed, and lying

on her back with her legs spread apart, and who was also killed by a single

gunshot wound. Id. at 380, 682 S.E.2d at 916.

A Fairfax County grand jury indicted Prieto in 2007 for, among other

crimes, the premeditated murder of Fulton and the willful, deliberate, and

premeditated killing of . . . Raver in the commission of or subsequent to rape. Id.

at 375, 682 S.E.2d at 914. After extradition to Virginia and one mistrial, a second

jury found Prieto guilty of two counts of capital murder, two counts of use of a

firearm in the commission of murder, rape, and grand larceny. Id. at 377, 682

S.E.2d at 914. The jury recommended the death sentence for both capital

convictions, and the trial judge imposed it. Id. The Supreme Court of Virginia

affirmed the convictions but vacated the death sentences, remanding for a new

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 25 of 77

10

penalty proceeding on the capital murder convictions. Id. at 418, 682 S.E.2d at

938.

On remand, a jury unanimously found both aggravating factors of future

dangerousness and vileness, either of which provides sufficient grounds for the

imposition of the death penalty . . . and again recommended two death sentences.

Prieto v. Virginia, 283 Va. 149, 157, 721 S.E.2d 484, 489 (2012) (Prieto II). The

evidence of Prietos prior crimes included felony convictions for:

a drive-by shooting of three people on or about August

25, 1984 and an escape committed on or about August

16, 1985 [;] . . . a series of crimes committed in

California on or about September 2, 1990: the rape and

murder of a 15 year old girl, two attempted murders, two

additional rapes, three kidnappings, two robberies, two

attempted robberies, and possession of a firearm by a

felon. Prieto I, 278 Va. at 380, 682 S.E.2d at 916.

On J anuary 13, 2012, the Supreme Court of Virginia affirmed the imposition

of the death sentence. Prieto II, 283 Va. at 157, 721 S.E.2d at 489. On October 1,

2012, the U.S. Supreme Court denied Prietos petition for certiorari. Prieto v.

Virginia, 133 S. Ct. 244 (2012) (Prieto III). On September 12, 2013, the Supreme

Court of Virginia denied his State habeas petition. Prieto v. Warden of the Sussex

I State Prison, 286 Va. 99, 748 S.E.2d 94 (2013) (Prieto IV). The District Court

for the Eastern District of Virginia has ordered Prietos counsel to file his federal

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 26 of 77

11

habeas petition by no later than April 2, 2014. Prieto v. Davis, Mem. Order, No.

3:13-cv-849 (E.D. Va. J an. 8, 2014) (ECF#21) (Prieto V).

B. Virginias other offenders currently on death row.

The other death-row inmates housed at Sussex I State Prison were also

sentenced to death for egregious crimes.

Ricky J avon Gray. Gray was convicted of murdering a family of four

Kathryn and Bryan Harvey, their 9-year-old daughter Stella, and their 4-year-old

daughter Rubyduring a New Years Day robbery in 2006. Gray v. Virginia, 274

Va. 290, 645 S.E.2d 448 (2007), cert. denied, 552 U.S. 1151 (2008). Gray forced

the family to the basement of their home, bound their hands and feet, slit their

throats with a razor knife, repeatedly bludgeoned their heads with a claw hammer,

and stabbed them with a knife; when the victims stopped moving, he set fire to

their house. Id. at 296-97, 645 S.E.2d at 452-53. Gray confessed to other crimes:

murdering three members of another family in a separate incident the same day, id.

at 299, 645 S.E.2d at 454; repeatedly stabbing another man the night before, id. at

300, 645 S.E.2d at 454-55; and bludgeoning his wife to death with a lead pipe, id.

at 299, 645 S.E.2d at 454.

Anthony Bernard J uniper. On J anuary 16, 2004, J uniper murdered his

girlfriend, Keshia Stephens, two of her daughters (ages 4 and 2), and Keshias

brother; he stabbed Keshia in the stomach with a knife and shot all the victims

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 27 of 77

12

multiple times. Juniper v. Virginia, 271 Va. 362, 376-77, 626 S.E.2d 383, 393-94,

cert. denied, 549 U.S. 960 (2006). While the two-year-old was still in her mothers

arms, J uniper shot the toddler four times, including firing a bullet into the crown of

the childs head. Id. at 376-77, 626 S.E.2d at 394.

William J oseph Burns. Burns was convicted of raping, anally sodomizing,

and murdering his 73-year-old mother-in-law in 1998. Burns v. Virginia, 261 Va.

307, 313, 541 S.E.2d 872, 877, cert. denied, 534 U.S. 1043 (2001). He inflicted

multiple injuries to her head and chest and caused 24 fractures to her ribs, one of

which may have punctured her heart. Id. at 315, 541 S.E.2d at 878-79. His other

convictions included felony theft, breaking and entering, malicious destruction of

property, resisting arrest, battery, assault, disorderly conduct, and a third-degree

sex offense. Id. at 318, 541 S.E.2d at 880.

Marc Eric Lawlor. Lawlor was convicted of the 2008 beating death of

Genevieve Orange, whom Lawlor also sexually assaulted. Lawlor v. Virginia, 285

Va. 187, 209, 738 S.E.2d 847, 859, cert. denied, 134 S. Ct. 427 (2013). Lawlor

bludgeoned her 47 times with various objects, including a metal pot and frying

pan. Id.

William Charles Morva. Morva was convicted of murdering two men in

2006 while in custody, awaiting trial on burglary and firearm charges. Morva v.

Virginia, 278 Va. 329, 683 S.E.2d 553 (2009), cert. denied, 131 S. Ct. 97 (2010).

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 28 of 77

13

While claiming to need medical attention, Morva escaped from the local hospital,

attacked and knocked unconscious a sheriffs deputy, stole his gun, and used it to

kill an unarmed hospital security guard by shooting him in the face from two feet

away, despite that the guard tried to surrender. Id. at 335-36, 683 S.E.2d at 557.

Before being apprehended the next day, Morva also killed a sheriffs deputy by

shooting him in the back of the head. Id. at 336-37, 683 S.E.2d at 557.

Thomas Alexander Porter. Porter was convicted for the 2005 murder of

Norfolk police officer Stanley Reaves after Reaves responded to reports that Porter

was brandishing a firearm and threatening a group of women in a nearby

apartment. Porter v. Virginia, 276 Va. 203, 216-17, 661 S.E.2d 415, 419-20

(2008), cert. denied, 556 U.S. 1189 (2009). When Officer Reaves arrived to

question him, Porter shot Reaves three times in the head and neck. Id. at 218, 661

S.E.2d at 420-21.

Ivan Teleguz. Teleguz was convicted of murder for hire in connection with

the 2001 slaying of Stephanie Sipe, his ex-girlfriend and mother of his infant son.

Teleguz v. Virginia, 273 Va. 458, 467, 643 S.E.2d 708, 714 (2007), cert. denied,

552 U.S. 1191 (2008). One of the two men hired by Teleguz, following his

instruction that he wanted Sipes throat cut, stabbed Sipe in her trachea, larynx

and esophagus, severing a major artery. Id. at 468, 643 S.E.2d at 714-15.

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 29 of 77

14

C. The professional judgment of Virginias prison officials about the

importance of segregating death-row offenders.

Prietos counsel deposed Virginias senior prison officials, including the

agency head and the warden at Sussex I State Prison. Defendant Harold C. Clarke

is the Director of the Virginia Department of Corrections, where he has served

since 2010. (J A 580, 583). He is the official responsible for promulgating the

Departments policies. (J A 593.) Director Clarke has worked as a corrections

professional for forty years (since 1974), including prior service as the Director of

the Nebraska Department of Corrections, the Secretary of Corrections for

Washington State, and the Commissioner of Corrections for the Commonwealth of

Massachusetts. (J A 583-84, 588, 591.)

The warden at Sussex I State Prison is Keith W. Davis. (J A 435.)

1

Davis

has worked for the Virginia Department of Corrections for 30 years. (J A 290.)

J ames Parks is the Director of Offender Management Services for the Department

of Corrections, where he has worked for 24 years. (J A 694, 698.) Defendant A.

David Robinson is Chief of Corrections Operations. (J A 340.)

The Defendants testified as to why, in their professional judgment, it was

important for death-row inmates to be confined in segregated conditions in a

single, maximum security facility, and not to be considered for housing among the

1

Defendant Eddie L. Pearson was the warden of Sussex I State Prison when Prieto

filed his lawsuit. (J A 195, 340.)

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 30 of 77

15

general prison population. (See, e.g., Clarke Dep. at J A 634-36, 639-48, 650-53,

656-60, 674, 678-79, 686-87; Robinson Dep. at J A 262, 573 (the propensity for

something to go wrong [is] a lot more severe and if it goes wrong, it could be very

serious); Davis Dep. at J A 286; Parks Dep. at 724, 753.)

As Director Clarke put it:

Theyre segregated because we see those individuals as

potentially the most desperate of all the offenders.

Again, they have been sentenced to die. They have

nothing to lose. They dont even look forward to a life in

prison in which they can improve themselves, change

their ways, [and] help other individuals for the rest of

their life until they die of natural causes. They have been

sentenced to die and as soon as the appeal process is

completed, a date is set, that sentence will carry out. (J A

639 (emphasis added).)

Clarke explained that, although death-row inmates may act out less often than

other prisoners, particularly when pursuing their legal efforts to avoid execution

(J A 653), they sometimes lash out when legal setbacks occur (J A 655). He also

testified how prisoners who may outwardly appear to have repented may simply

be playing games, cautioning that when we misread whats going on it can be

catastrophic. (J A 648.)

Director Clarke explained his concern that permitting death-row offenders to

congregate with other prisoners would pose an unacceptable safety risk. He

described an incident in the 1980s in which death-row inmates who had been

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 31 of 77

16

permitted to congregate at the maximum security prison in Mecklenberg staged a

mass escape, an incident that could have been catastrophic had they not been

apprehended. (J A 643.)

He further testified that, while no prisoner had yet escaped from Sussex I

State Prison, there was a much higher risk of escape from among the general

population housed there than from its death-row unit:

[O]ffenders in general population are moving about, they

can see the fences. They can plan. They can study staff

patterns of behavior and so forth and eventually find a

way out.

I have been in this business long enough where there

have been escapes from high security facilities where

offenders did just exactly what I said. They have all the

time in the world to sit in the yard, to become familiar

with staff, to become familiar with patterns of behaviors,

the way things are done, and they can execute. And

when they do it youll be left wondering where are they

as they found that one seam theyre able to get through.

And that is not something that we would want to ever

occur with an offender whos on death row. (J A 644-45.)

D. Virginias prison-housing policies.

The Virginia Department of Corrections operates more than three dozen

correctional units and other major facilities throughout the Commonwealth,

including Sussex I State Prison with its segregated unit for death-row prisoners.

2

2

See http://vadoc.virginia.gov/facilities/ (listing facilities).

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 32 of 77

17

The Department is responsible for approximately 39,000 prisoners. (J A 617-18.)

It has been quite successful in meeting its goals. (J A 713.) The Department, in

fact, has experienced relatively little unrest at its facilities and fewer prisoner

assaults compared to prison systems in other States. (Id.; J A 621 (very

successful).)

As noted above, death-row prisoners are automatically sent to death row at

Sussex I State Prison. Operating Procedure 830.2(D)(7) provides that [a]ny

offender sentenced to Death will be assigned directly to Death Row . . . . (J A

196, 199, 221.) The Procedure further states that they will not be considered for

reclassification to a different facility. (J A 199, 221, 227.19.) Operating Procedure

460.A(I), Security of Offenders Under the Sentence of Death, likewise establishes

a policy to prohibit death-row offenders from being housed with general

population prisoners. (J A 941.)

By contrast, all non-death-row prisoners are evaluated under a classification

system to determine where to house them. The scoring system decides their

placement at facilities ranging from minimum security, Level 1 facilities, to

maximum-security Level 5 facilities, to even more restrictive segregation for

disruptive and assaultive offenders at a Level S facility like Red Onion State

Prison. (J A 219, 622-23.)

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 33 of 77

18

The general prison-population housing at Sussex I State Prison is a Level 5

facility; approximately 1,000 prisoners are housed there. (J A 295). It has

approximately 126 prisoners in administrative segregation. (Id.) (The death row

unit is isolated from the rest of the prison and has 44 segregated cells. (J A 370).)

To decide where to place non-death-row prisoners, the Security Level

point-scoring system uses the following eight factors:

history of institutional violence;

severity of current offense;

prior offense history severity;

escape history;

length of time remaining to serve;

current age;

prior felony convictions; and

other stability factors. (J A 244.)

Then, based on various mitigating and aggravating factors, prison officials may use

their discretion to increase or decrease the prisoners score. (J A 220.) Additional

factors determine whether non-death-row prisoners qualify for administrative

segregation (solitary confinement), such as whether they have committed

aggravated assaults on staff, present serious escape risks, or have seized or held

hostages. (J A 223-24.) General population prisoners may also be held in

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 34 of 77

19

segregative confinement for disciplinary reasons, but disciplinary segregation does

not exceed 60 days. (J A 623.)

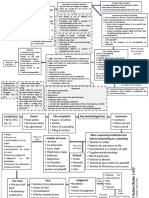

The scoring thresholds set forth in Operating Procedure 830.2 (at J A 219)

are as follows:

Thus, prisoners with a score of 32 points or higher would be sent to a Level 5

facility like Sussex I State Prison. Non-death-row prisoners are then evaluated

annually to review whether their placement is appropriate. (J A 221-23; 624-25.)

3

Because the computer system that tracks each prisoners place of

confinement requires inputting a Security Level number for all inmates, prisoners

sentenced to death are assigned the number 99 to reflect their categorical

assignment to death row. As the official responsible for operating the computer

system explained: Thats the only way the system will take it . . . . [The number]

99 has no other significance . . . . (J A 749.)

3

Misconduct by a prisoner may trigger a classification review before the annual

review. (J A 222-23.)

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 35 of 77

20

E. Prietos complaints about conditions on death row.

If Prieto were housed in the general population of a Level 5 facility like

Sussex I State Prison, his prison mates would include persons convicted of

offenses ranging from driving under the influence and violating parole, to habitual

offenders driving on suspended licenses, to more serious offenders convicted of

murder, robbery and rape. (J A 296.) Prietos counsel argued in the District Court,

however, that given Prietos good conduct since his arrival on death row, he would

score 25 points (before any discretionary adjustments) if death-row inmates like

him were evaluated as if they were serving a life-without-parole sentence for

murder. (J A 777-81.) A score of 25 would make him eligible to be housed in a

Level 3 facility. (J A 219.) His counsel allowed that discretionary review could

properly place Prieto instead in a Level 4 or Level 5 facility (J A 789, 791-92) but

said Prieto would object to it as disingenuous if prison officials used their

discretion to conclude that he should remain in segregated conditions based solely

on the capital offenses for which he has been sentenced to death (J A 813-14).

Prietos other complaints about his death-row housing included:

that he is kept in his cell for 23 hours a day and must take all three meals

there. (J A 204.) But the same is true of prisoners held in administrative

segregation (including those housed at Level S facilities). (J A 334-35, 684);

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 36 of 77

21

that he has minimal human contact. Other than interactions with the units

guards, infrequent visits by my attorneys, and when I occasionally cut

another inmates hair, I have almost no other human contact, he said. (J A

205.) But death-row inmates are also visited by a mental health practitioner

at least once a week and receive twice daily visits from medical personnel.

(J A 437.) They are also afforded the opportunity of out-of-cell recreation

for one hour a day, five times per week, unless security or safety concerns

dictate otherwise. (J A 204, 437.) During out-of-cell recreation, they may

see and converse with other death row offenders in the recreation area.

(J A 437.)

that he is not permitted to have contact visits with family members. (J A

206.) But the same is true of prisoners in administrative segregation and

Level S segregation. (J A 392.) Offenders on death row and in

administrative segregation are permitted, however, to have non-contact and

video visitation during the same visiting hours enjoyed by general popula-

tion prisoners. (J A 328, 392, 438.) And at the Wardens discretion, death-

row inmates may be permitted contact visits with immediate family

members every six months. (J A 392, 349-50, 681-82.) The record reflects

that none of the 11 contact-visit requests by death-row inmates between

September 2008 and December 2012 was granted (J A 350), but that statistic

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 37 of 77

22

sheds no light on the circumstances why. And although Prieto complained

that every request I have ever submitted to have a contact visit with

immediate family has been denied by the Warden, he admitted in the same

affidavit that [a]ll of my immediate family lives in California and I rarely

have visitors. (J A 206.)

that he has a poor view from his window. Indeed, Prietos prison-conditions

expert explained that poor-window views are common in solitary

confinement at prisons in other States, looking out on virtually nothing that

is visually appealing; some cells, like those at Pelican Bay in California,

have no window at all. (J A 408.) But the evidence below actually showed

that, while an inmate standing on the floor of a death-row cell at Sussex I

State Prison would see only sky, by elevating oneself (such as by standing

on the bed next to the window, see J A 938, 939), a person can see fields,

trees, things of nature. (J A 358.) The windows there are also the same size

as in general population cells, except that the windows in both death-row

and administrative-segregation cells have wire mesh across them to prevent

prisoners from burning holes in the Plexiglass through which to pass

contraband. (J A 278, 322.) Wire mesh is being installed on the windows in

the general population cells too, but not all have been outfitted yet; prison

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 38 of 77

23

officials started first with the cells on death row and in administrative

segregation units. (J A 322.)

that the cells are small and Prieto must rotate cells every month. (J A 205,

411.) But the cells on death row are comparable in size to cells in the

general population units. (J A 437.) The cells measure 71 square feet. (J A

343, 823; see Photographs at J A 938, 940.)

4

Offenders in the general

population, by contrast, must share a cell with another inmate. (J A 467.) So

death-row offenders actually have more personal space than general

population prisoners. And cell rotation is necessary to guard against escape

efforts, concealed weapons, and contraband. (J A 285.)

that death-row prisoners cannot attend religious services, unlike prisoners in

the general population. (J A 206, 309.) But death-row offenders are

permitted visits directly in their cell from the Institutional Chaplain and

approved religious volunteers, privileges not afforded to inmates in

disciplinary segregation. (J A 437.) Prieto, who is Catholic, admitted that he

4

The 71-square-foot figure comes from Director Clarkes sworn Interrogatory

Answers (J A 343) and was the figure found by J udge Brinkema in her

Memorandum Opinion (J A 823). Earlier estimates by Defendants used the figure

31.16 square feet. (J A 190, 196.) But Prietos expert pointed out that that estimate

was too low. (J A 410 n.7 (offering his impression . . . that the actual square

footage is closer to 50-60 square feet).) He noted that death-row cells nationwide

range from 55 to 90 square feet. (J A 406.)

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 39 of 77

24

did once successfully request a visit from a Catholic priest, although the

process was difficult. (J A 206.)

that death-row inmates have little to do to occupy their time. But they are

allowed to have a television and compact disc player in their cells, privileges

not afforded to offenders in administrative, Level S, or disciplinary

segregation. (J A 336, 355, 437, 684.) Death-row inmates may also

purchase commissary items, including food, whereas those in disciplinary

segregation may purchase only personal hygiene items and writing

materials. (J A 437, 688.) Death-row inmates also have the same telephone

privileges as prisoners in the general population8:30 a.m. to 9:30 p.m., 7

days per week. (J A 437.) Except, as Prieto explained, [i]f I need to make a

telephone call, a telephone is brought to my cell. (J A 205.)

that death-row inmates, like those in administrative segregation, are

ineligible to attend classes. (J A 325, 334.) But prison officials explained

that their limited resources do not allow for that. (J A 604-05, 641, 649-51,

656-58.) Similar resource constraints require denying such opportunities to

offenders serving life terms in the general prison population. (J A 605,

616.)

5

With regard to providing education and job training, the Department

places its priority on offenders who are closer in time to being released, in

5

Death-row offenders are the most expensive-per-inmate to house. (J A 266.)

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 40 of 77

25

order to facilitate their re-entry into civil society and reduce the risk of their

recidivism. (E.g., J A 602 (You can equate effective re-entry programming

with improved public safety . . . . Because when you do a good job with

effective reintegrating, they have options.).)

that he is not permitted to visit the law library; [s]ometimes [his] requests

for copies of legal decisions are delayed or ignored, and he cannot receive

legal texts, treatises or properly conduct legal research. (J A 205-06.) But

[w]ith regard to legal services, death row offenders have more access than

even offenders in the general population because of their ongoing appeals.

Death row offenders may request legal materials at any time, which are

delivered to their cells and [they] may request the phone to call their attorney

and set up a visit directly; offenders in disciplinary segregation must make a

request through their counselor for a legal call or visit. (J A 438; J A 463.)

that his cell is not totally dark at night; he may dim but not completely turn

off the nightlight in his cell, and he is not permitted to block out the light.

(J A 204.) But it is important, for safety and security reasons, for guards to

be able to see into an inmates cell at ANY time. (J A 200, 11.)

that his hands and feet are shackled whenever he leaves his cell. (J A 204.)

But the regulations require this for the safety of the guards and other

prisoners. (J A 167, 200.)

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 41 of 77

26

that he is permitted to shower three times a week and [t]here is no

temperature control. (J A 204.)

Prietos expert also opined that while Mr. Prieto was confined from 1992-

2006 on Californias death row at San Quentin, the conditions he experienced were

in some ways substantially less harsh. (J A 412.) In particular, he said, Prieto

could recreate 12 hours a week in a large yard at San Quentin, together with other

prisoners; use a punching bag; play cards, basketball, dominos, and ping pong with

other prisoners; and attend group religious activities. (Id.) Death-row inmates at

San Quentin also enjoyed liberal contact visits, and their cells had windows

allowing a pleasant view of the ocean, bridges, and boats passing by. (Id.)

But Director Clarke was not persuaded that Virginia should change its

approach. In his professional judgment, the risks were simply too great:

[W]e dont want to put ourselves in a position wherein

were going to treat this population as the general

population because of all of the things that could go

wrong. Theyre not similarly situated as offenders in the

general population . . . . [T]hey have been sentenced to

die and we expect that is going to go on anywhere from

seven, and as you said, to ten years. In the process -- in

the meantime theyre appealing the sentences and they're

being treated as humanly -- theyre given access to the

courts, doing all those things that are necessary and

mandated constitutionally. And to go beyond that I think

increases the level of risk that we will face in the

department and to which we will expose the people of the

Commonwealth . . . . (J A 678-79.)

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 42 of 77

27

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Federal courts reviewing prisoner complaints about the conditions of their

confinement are required to give substantial deference to the judgment of prison

officials. The Supreme Court and Fourth Circuit have repeatedly discussed the

inordinately difficult task of operating a prison and the need to defer to the expert

judgment of corrections officials in order to ensure the safety of prisoners, prison

staff, and the public at large. Deference to their professional judgment is required

even when prisoners claim that their conditions of confinement violate

fundamental constitutional rights, such as rights protected under the First, Fourth

and Eighth Amendments. J udicial deference is afforded not simply because prison

administrators have a better grasp of the conditions and dangers in the prisons they

operate, but because the task of prison administration is committed to the

responsibility of the executive and legislative branches. And where, as here, the

case involves a State penal system, federalism principles provide an additional

reason for deference.

This case involves no claim that conditions on Virginias death row

independently violate the Constitution. The District Court rejected Prietos Eighth

Amendment claim, and this Court dismissed his appeal because he failed to

prosecute it. Instead, the question here is whether Virginia law gives rise to a

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 43 of 77

28

State-created liberty interest on the part of capital offenders to be considered for

housing in the general prison population.

In addition to requiring the prisoner to identify a State-law liberty interest to

support his Due Process claim, however, the Supreme Court in Sandin v. Conner

imposed an additional barrier: the prisoner must show that his confinement

imposes atypical and significant hardship on the inmate in relation to the ordinary

incidents of prison life. 515 U.S. 472, 484 (1995). Sandin created that barrier

after the Court became concerned that its case law had created a disincentive for

prison officials to memorialize their procedures and an incentive for prisoners to

scour through prison regulations to find State-law grounds for demanding due

process. Sandin was meant to restrict condition-of-confinement claims, not to

make them easier to bring.

Sandin, and the Courts later decision in Wilkinson v. Austin, 545 U.S. 209

(2005), did not instruct lower courts how to decide the baseline for determining

whether the prison conditions in question are atypical. And neither Sandin nor

Wilkinson involved a claim by a death-row inmate. Nor has this Court decided the

relevant baseline for death-row offenders. Like Sandin and Wilkinson, Beverati v.

Smith, 120 F.3d 500 (4th Cir. 1997), involved general population prisoners who

were placed into segregative confinement. It did not evaluate condition-of-

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 44 of 77

29

confinement claims by death-row inmates, and nothing in Beverati suggests that

they should be compared to general population prisoners.

Death-row confinement is sui generis. Indeed, every court to consider the

question (with the exception, now, of the district court below) has held that the

baseline under Sandin for evaluating condition-of-confinement claims by death-

row inmates is the condition of confinement of other offenders that the State has

sentenced to death.

In any event, Prieto cannot satisfy the threshold requirement to identify a

liberty interest created under Virginia law that would entitle him to be considered

for housing in the general prison population. The Operating Procedures of the

Virginia Department of Corrections make clear that all capital offenders will be

housed on death row at Sussex I State Prison and will not be considered for

reclassification.

The District Court also erred by looking to death-row conditions in other

States. What other States may do is not probative of whether Virginia has created

a State-law entitlement on the part of death-row inmates to be considered for

housing in the general prison population. And the survey data Prieto introduced

into the record actually confirm that Virginia is not unique in its housing of death-

row offenders.

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 45 of 77

30

The District Court also erred in concluding that there is no difference

between death-row offenders and offenders sentenced to life in prison without

parole. Death-row offenders cannot be sentenced to death unless a jury or judge

has found that they pose a unique danger to society. Moreover, the District Court

improperly second-guessed the judgment of Virginias top corrections officials,

who gave extensive testimony below that it is important for security and the safety

of the public to house death-row offenders in segregative confinement, pending the

imposition of their sentence. Ignoring that testimony was error in light of the clear

directives of the Supreme Court and Fourth Circuit to defer to the professional

judgment of State prison officials. Virginias officials acted within their

reasonable professional judgment and expertise in determining that death-row

offenders have nothing to lose and present unique escape risks and dangers to other

prisoners and to the public.

The District Courts injunction is invalid on other grounds as well. It failed

to meet the requirements of Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(d) because it does not describe in

detail the acts required of Virginias prison officials. It also violated the Prison

Litigation Reform Act by overriding State law without including the required

findings that Federal law requires State law to be overridden, that such relief is

necessary to correct the violation of a Federal right, and that no other relief would

suffice.

Appeal: 13-8021 Doc: 22 Filed: 03/24/2014 Pg: 46 of 77

31

In this case, however, no injunction should have been entered at all because

Prieto failed to satisfy either of Sandins predicates for establishing a State-law

liberty interest. Accordingly, the complaint should be dismissed and the injunction

dissolved, and the award of costs and attorneys fees to Prieto should be vacated.

ARGUMENT

This Court reviews de novo a district courts decision to grant summary

judgment. Hill v. Lockheed Martin Logistics Mgmt., Inc., 354 F.3d 277, 283 (4th

Cir. 2004) (en banc). Where, as here, the Court is faced with cross-motions for

summary judgment, it should review each motion separately on its own merits

to determine whether either of the parties deserves judgment as a matter of law.

VCA Cenvet, Inc. v. Chadwell Animal Hosp., LLC, No. 13-1369, 2014 U.S. App.

LEXIS 869, at *5-6 (4th Cir. J an. 16, 2014) (quoting Rossignol v. Voorhaar, 316

F.3d 516, 523 (4th Cir. 2003)). In considering each individual motion, [the Court

should] resolve all factual disputes and any competing, rational inferences in the

light most favorable to the party opposing that motion. Id. at *6 (citation and

quotation omitted).