Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Getting Kids To Eat Their Vegetables

Uploaded by

WAMU885newsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Getting Kids To Eat Their Vegetables

Uploaded by

WAMU885newsCopyright:

Available Formats

Getting Kids to Eat Their Vegetables

By Caitlin Friess

November 22, 2013

RESEARCH

Professor Anastasia Snelling knows that, given a choice, elementary school students in

D.C. prefer to take their broccoli Asian-style, with a dressing of soy sauce, ginger, and

garlic. She learned this piece of information through a USDA-funded study of the

consumption of three vegetables throughout the year in order to implement a specific

behavioral economic strategy. This testin this case, a taste testincludes the

preparation of the target vegetable in three different ways, where students have the

opportunity to select which option they like the most. The next time that vegetable is

offered in the cafeteria, the winning preparation will be served.

Local- and national-level healthy eating policies usually include an increased

presentation of fresh fruits and vegetables to students, as well as whole grains, beans,

and lentils. That makes all of us feel good, that students are at least having these foods

offered to them, she says. But what has become very apparent is that offering a

vegetable doesn't necessarily mean a student will consume it.

Snelling and a group of graduate students from the health promotion management

program are conducting these test in eight schoolsfour in D.C. and four in Arlington

using broccoli, black beans, and spinach. All of the schools have greater than 50

percent of the students eligible for free or reduced lunch.

The difference in how D.C. and Arlington conduct their cafeterias has become key to the

study. D.C. has a serve model in place, whereas Arlington has an offer model. This

means that students in Arlington get to choose what goes on their plates while students

in D.C. just have the food given to them.

After collecting data for three months, it has become clear that a different behavioral

economic strategy may be necessary in Arlington. Every student has the same plate in

D.C. Snelling says. It all looks the same: a meat or protein entree, a starch,

vegetables, and fruits. Arlington students can choose the black bean corn salsa in the

taste test, but end up choosing the fruit in the cafeteria. What we have observed with

the offer versus serve food service model is that there is less waste with the offer

model, because if a student doesn't want it, it doesn't end up on their plate and

potentially in the trash.

In previous studies under the offer model, Snelling implemented what she calls an

appetizer strategy, where students can get a bite of the vegetable being served for

lunch while they are in line, and if they like it, the experience is at the forefront of their

thoughts, making them more likely to choose and eat the vegetable. It's a challenge,

but it's a good illumination of what's going on in the natural environment, Snelling says.

Basically, the reason we haven't been too successful in Arlington has come down to

too many food choices.

For their current research, broccoli is the only vegetable to have been through the whole

experimental cycle, which includes a baseline test, the taste test, and two follow-ups in

each school. We're using an iPhone application developed by Brigham Young

University called the V-Project, graduate student Devin Ellsworth says. The two

graduate students per school will be there for all lunch periods, and they're recording

the gender of the child, the lunch period, and how much of the vegetable student

consumed.

If the child did not eat any of the vegetable, it is recorded as a zero. If they tried even a

little of it, the students put it in as 50 percent, and if they finished all of the vegetable it is

recorded as 100 percent. The totals for each school give the researchers a percentage

of how many children tried the vegetable versus ate it all or didn't touch it. We get great

feedback from kids; they're really engaged in the process, Ellsworth says. It's funny

how deliberative they can be, how they taste it and sit there and think really hard about

it before they move on.

The group has seen overall positive results in D.C., with broccoli consumption going up

to 65 percent from 35 percent. In Arlington, they have seen more mixed results. We

believe we are nudging two behaviors in Arlington because of its offer model, Snelling

says. We have to nudge them to take the vegetable and then we have to nudge them

to eat it.

Snelling sees her research as an important part of the push for healthy eating. We're

really addressing the issue of health disparities very early in a childs life, trying to get

children exposed to good vegetable choices, she says. It's only one part of the health

disparity issue, but it is one way to reach the children who need these services the

most.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Council of Government Fire Chiefs Metro Rail Transit Fire Rescue AgreementDocument40 pagesCouncil of Government Fire Chiefs Metro Rail Transit Fire Rescue AgreementWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Young D.C. April 2000 IssueDocument2 pagesYoung D.C. April 2000 IssueWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Community Council Minutes, Dec. 3, 2014 MeetingsDocument8 pagesCommunity Council Minutes, Dec. 3, 2014 MeetingsWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Community Council Minutes, Sept. 17, 2014Document7 pagesCommunity Council Minutes, Sept. 17, 2014WAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- ACS 12 5YR S1001 DC GrandfamiliesDocument4 pagesACS 12 5YR S1001 DC GrandfamiliesWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Streetcar Logs From The State Safety Oversight OfficeDocument6 pagesStreetcar Logs From The State Safety Oversight OfficeWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Executive Action Poll Results From Latino DecisionsDocument3 pagesExecutive Action Poll Results From Latino DecisionsWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Maryland House Majority Leader Anne Kaiser's State of The State ResponseDocument3 pagesMaryland House Majority Leader Anne Kaiser's State of The State ResponseWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Preliminary Timeline of Deadly Incident On Yellow LineDocument2 pagesPreliminary Timeline of Deadly Incident On Yellow LineWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Two-Year Action Plan For moveDCDocument12 pagesTwo-Year Action Plan For moveDCWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Hispanic Children's Coverage: Steady Progress, But Disparities RemainDocument17 pagesHispanic Children's Coverage: Steady Progress, But Disparities RemainWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Basic Info and Stats About DREAMers For The DMV AreaDocument1 pageBasic Info and Stats About DREAMers For The DMV AreaWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Community Council Minutes, May 7, 2014Document6 pagesCommunity Council Minutes, May 7, 2014WAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Fairx County Memo On Unaccompanied MinorsDocument22 pagesFairx County Memo On Unaccompanied MinorsWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- State of D.C. Schools Speech by Kaya HendersonDocument7 pagesState of D.C. Schools Speech by Kaya HendersonWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

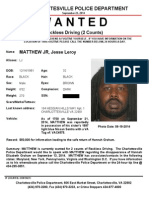

- Wanted Poster For Jesse MatthewDocument1 pageWanted Poster For Jesse MatthewWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Washington D.C. Rankings in ACSM American Fitness IndexDocument2 pagesWashington D.C. Rankings in ACSM American Fitness IndexWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Connecting Youth in Montgomery County To OpportunityDocument36 pagesConnecting Youth in Montgomery County To OpportunityWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Letter To The Kenyan Ambassador From Attorney For Lucia MwakaDocument5 pagesLetter To The Kenyan Ambassador From Attorney For Lucia MwakaWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Dangerous by DesignDocument20 pagesDangerous by DesignSAEHughesNo ratings yet

- Smithsonian Report On The Last Passenger PigeonDocument17 pagesSmithsonian Report On The Last Passenger PigeonWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Office of Consumer Protection ReportDocument4 pagesOffice of Consumer Protection ReportWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Minutes of The Feb. 19 Meeting of The WAMU 88.5 Community CouncilDocument5 pagesMinutes of The Feb. 19 Meeting of The WAMU 88.5 Community CouncilWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Letter For Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx To State Departments of TransportationDocument4 pagesLetter For Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx To State Departments of TransportationWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- DHS LetterDocument2 pagesDHS LetterWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Earth Force FlyerDocument1 pageEarth Force FlyerWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Arkansas Ave Safety Update 4 9 14Document6 pagesArkansas Ave Safety Update 4 9 14Michael PhillipsNo ratings yet

- State of The District Address 2014Document13 pagesState of The District Address 2014WAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- The Lieutenant Don't Know ExcerptDocument3 pagesThe Lieutenant Don't Know ExcerptWAMU885newsNo ratings yet

- Sweetapolita's Gingeriest Ginger Molasses CookiesDocument3 pagesSweetapolita's Gingeriest Ginger Molasses Cookiesluke.renaudNo ratings yet

- Module 11: Sugar - RefiningDocument35 pagesModule 11: Sugar - RefiningsenaNo ratings yet

- Dental Aligners: How Do Aligners Work?Document2 pagesDental Aligners: How Do Aligners Work?nevin vargheseNo ratings yet

- PT Q3 English 3Document7 pagesPT Q3 English 3Joanne Crystal AzucenaNo ratings yet

- Ramadan Philips Big Sale: e - CatalogueDocument7 pagesRamadan Philips Big Sale: e - Cataloguedidit_adithyaNo ratings yet

- Peter Ochieng Trade PROJECTDocument30 pagesPeter Ochieng Trade PROJECTNickson SangNo ratings yet

- Instant Noodles Product Overview and HistoryDocument65 pagesInstant Noodles Product Overview and Historyvivek_limbu100% (3)

- Processing Conditions For Producing French Fries From Purple-Fleshed SweetpotatoesDocument8 pagesProcessing Conditions For Producing French Fries From Purple-Fleshed SweetpotatoesBagas SamodroNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Flavor ChracterizationDocument515 pagesHandbook of Flavor Chracterizationbraun54000No ratings yet

- How To Kiss Care and Caress BreastsDocument40 pagesHow To Kiss Care and Caress BreastsRoel PlmrsNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Benefits and Risks of Moderate Alcohol Consumption - UpToDateDocument17 pagesCardiovascular Benefits and Risks of Moderate Alcohol Consumption - UpToDateAnca StanNo ratings yet

- Fortified Rice Pellets - A Game Changer in Context of Malnutrition - 111021Document3 pagesFortified Rice Pellets - A Game Changer in Context of Malnutrition - 111021Sayid Naiman AhmadNo ratings yet

- Ch6 Nutrition in HumanDocument10 pagesCh6 Nutrition in HumanNinjago Is PerfectNo ratings yet

- Statics and Probability Health DietDocument5 pagesStatics and Probability Health Dietkathyrin anocheNo ratings yet

- Yvette Schlee Publisherapplication 2Document2 pagesYvette Schlee Publisherapplication 2api-399286807No ratings yet

- Golf Clubhouse Design and Supporting Facilities Site PlanningDocument24 pagesGolf Clubhouse Design and Supporting Facilities Site PlanningSanjay KumarNo ratings yet

- Grammar For The Mid-TermDocument5 pagesGrammar For The Mid-TermNatia TughushiNo ratings yet

- FSSC 22000 V. 5 GAP ANALYSISDocument3 pagesFSSC 22000 V. 5 GAP ANALYSISMarc Dennis Angelo UgoyNo ratings yet

- Financial Analysis 4Document27 pagesFinancial Analysis 4Chin FiguraNo ratings yet

- Idiocracy ButtFuckers MenuDocument2 pagesIdiocracy ButtFuckers Menue86yeewy1zNo ratings yet

- Plano Ach (Ac1-Ac8)Document6 pagesPlano Ach (Ac1-Ac8)irpanhdtlhNo ratings yet

- Digestive System: Name: Azza Ferista Delvia Ninda Sa Ri O Kta Imelda Ikhda La Tifatun Naim Cla SS: 4BDocument7 pagesDigestive System: Name: Azza Ferista Delvia Ninda Sa Ri O Kta Imelda Ikhda La Tifatun Naim Cla SS: 4BMaulana RifkiNo ratings yet

- Occupational Health Hazards Faced by Workers in The Minor Chilli Processing IndustryDocument4 pagesOccupational Health Hazards Faced by Workers in The Minor Chilli Processing IndustryVivek Singh100% (2)

- Haccp: I. B. Agung Yogeswara, S.TP., M.SC, PHD (Cand)Document33 pagesHaccp: I. B. Agung Yogeswara, S.TP., M.SC, PHD (Cand)ANDI RANEVERNo ratings yet

- Erowid MAOI Vault - Foods To AvoidDocument12 pagesErowid MAOI Vault - Foods To AvoidWiktoria Klara WalęckaNo ratings yet

- Rotation 4 Roleplay ScriptDocument2 pagesRotation 4 Roleplay ScriptDwynwen Aleaume GumapacNo ratings yet

- Strategies 19-26Document8 pagesStrategies 19-26Tor ToteNo ratings yet

- ALH Starter Wordlist U5Document6 pagesALH Starter Wordlist U5Phạm Minh AnhNo ratings yet

- UV Cutoff: Solvents Arranged by Increasing UV Absorbance WavelengthDocument2 pagesUV Cutoff: Solvents Arranged by Increasing UV Absorbance Wavelengthjoy rajNo ratings yet

- Food Uses of GingerDocument7 pagesFood Uses of Gingerbash kinedNo ratings yet