Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ayala Surrealism Chilean Poetry

Uploaded by

valeriadelosrios0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

52 views20 pagesSurrealism In Latin America had an enormous infuence on literature during the frst half of the twentieth century, says matias ayala. In the second half of the century, surrealism was diluted by the general impact of the avant-garde, he says. Ayalsa: surrealism is paradoxically confronted with its inadaptability in a "pure" form.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentSurrealism In Latin America had an enormous infuence on literature during the frst half of the twentieth century, says matias ayala. In the second half of the century, surrealism was diluted by the general impact of the avant-garde, he says. Ayalsa: surrealism is paradoxically confronted with its inadaptability in a "pure" form.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

52 views20 pagesAyala Surrealism Chilean Poetry

Uploaded by

valeriadelosriosSurrealism In Latin America had an enormous infuence on literature during the frst half of the twentieth century, says matias ayala. In the second half of the century, surrealism was diluted by the general impact of the avant-garde, he says. Ayalsa: surrealism is paradoxically confronted with its inadaptability in a "pure" form.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 20

179

THE PHOTOGRAPHIC LEGACY OF SURREALISM

IN LATE-TWENTIETH-CENTURY CHILEAN POETRY

MATAS AYALA

Surrealism in Latin America had an enormous infuence on literature during

the frst half of the twentieth century, as evidenced by the many tributes and

publications from Mexico, Chile, Peru, and Argentina dedicated to the move-

ment.' Moreover, it is well known that concepts such as lo real maravilloso and

magical realism can be traced to the treatment of the uncanny and the fantastic

in surrealism. However, in the second half of the century, surrealist infuence in

Latin America was diluted by the general impact of the avant-garde. For exam-

ple, many avant-garde motifs and proceduressuch as chance, automatism,

and montagethat in Latin America appeared to be an infuence of surreal-

ism were likewise employed by Dadaism in diferent contexts and with difer-

ent results. Besides a handful of authors that clearly belong to the surrealist

hinterland, which persists today, the most important Latin American literary

movements (estridentismo [stridentism], ultrasmo [ultraism], creacionismo

[creationism]) and magazines (Martn Fierro, Amauta) did not adhere to the

tenets of surrealism.

Surrealism is, then, paradoxically confronted with its inadaptability in a

pure form. As the critic Valentn Fernidn states in a polemic article, surreal-

ism infuenced the most important poets of the Latin American avant-garde

(Oliverio Girondo, Pablo Neruda, Csar Vallejo), but none of them strictly

identifed themselves as surrealists. In Latin America, European surrealism

took on a new form, one mixed with romantic subjectivity, political programs,

and the discourse of trans-culturalism, as with the novelist Alejo Carpentiers

concept of lo real maravilloso. Taken as a whole, the poetry of Octavio Paz, the

foremost promoter of surrealism afer World War II, can at best be character-

ized as quasi-surrealist. Tere are books by Paz that are more clearly associated

with surrealism, such as guila o sol? (:,:; Eagle or Sun?, :,o), but his work

seems today to be an owl of Minerva fying at dusk, as his insistence on the

importance of this movement for twentieth-century literature is more in recog-

nition of its legacy than its validity as a future program for avant-garde poetics.

In the following pages, I will problematize some of this diluted surrealist

legacy by discussing three Chilean poets who emerged during the :,os and

:8os: Juan Luis Martnez (::,), Ral Zurita (b. :,o), and Claudio Bertoni

180

AYALA

(b. :o). None of them identifed himself as a surrealist, but all of them have

recognized the infuence of surrealism on their production. Although diver-

gent in their respective aesthetic projects, these poets all incorporated photog-

raphya medium that became an important documentary tool in a troubled

Chile during the :,os and :8osinto their literary works to create layers of

meaning and additional complexity, revealing the infuence of surrealist tech-

niques. Te relationship between surrealism and photography has been studied

from several viewpoints: photographys interaction with text in magazines and

books, photography as the unconscious of surrealism,` and the use of photog-

raphy to explore a variety of themes such as the city, desire, and orientalism.

I will show how these poets used photography to renew some classic surrealist

motifs, including the use of text and image as a conceptual enigma in the works

of Martnez, dream and fantasy as the occasion for redemption in Zurita, and

the city as a space of aleatory encounters in Bertoni.

Photography and the Marvelous in Juan Luis Martnezs La nueva novella

Juan Luis Martnezs La nueva novela (:,,; Te new novel) is both a hermetic

and a playful work. Tis is apparent from the cover of the book, where, in place

of the traditional name of the author, two names are crossed out (fg. :). Te

surrealist infuence is manifest in the books combination of estrangement and

humor, nonsense and play, and the uncanny and ludic. Indeed, Martnezs work

pushes the bounds of a traditional book of poetry. Te work can be justifably

characterized as an art book due to the consistent design,

which features the

repetition of diferent book elementsfor example, title, epigraph, numbered

parts, and footnotes. Te actual text, most of which is prose, is minimal and

eccentric. Much of La nueva novela comprises pastiches of citations, intertex-

tual references, images, and collages.

Te images in Martnezs work ofen move beyond a supplemental and dec-

orative function to become the centerpiece. Tese images have diverse prov-

enance: some are drawings by the author, others are photographs from books

and magazines, advertisements, and even reproductions of high art. More

important than the origin of these images is how the juxtaposition of text and

image creates multiple associations through repetition, doubling, cropping, and

collage. Allusion and fragmentation are brought to the fore, sacrifcing seman-

tic clarity. Martnez makes numerous direct references to Dadaist and surreal-

ist authors as he employs avant-garde practices such as the clear opposition

to realism, the negation of conventional notions of genre, and the rejection of

tradition as a source of authority. Just as with the classic works of European

surrealism, La nueva novela plays with the idea of the book and refects upon

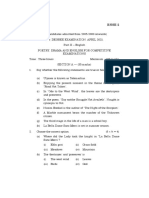

Fig. 1.

Cover of Juan Luis Martnez,

La nueva novela (Santiago:

Ediciones Archivo, 1985).

181

THE PHOTOGRAPHIC LEGACY OF SURREALISM

182

AYALA

language and extralinguistic codes, the transmission of knowledge, and the

ofen thin line between nonsense and meaning.

Te text El revlver de cabellos blancos (Te revolver with white hair)'

takes its title from a book of poetry by Andr Breton and reproduces an image,

inverted at a o-degree angle, of the white-haired French poet smoking a

pipe (fg. :). Te epigraph of Martnezs text is by the French writer Maurice

Blanchot: Ruptura, carencia, hueco, he aqu la trama de lo textual (lo de den-

tro, lo de fuera, el tejido capilar) (Rupture, absence, emptiness, here the text

is woven [what is lef in, what is lef out, the capillary tissue]). Te text atop

the upper part of the imagefragmented, cropped, and pasted like a paper

collagerewrites the epigraph, shifing the content from the textual realm

to reality:

Ruptura, carencia, hueco, he ah la trama de lo real: (la vida, la muerte: lo

de dentro, lo de fuera): la cabeza disparando desde la pgina(la fjacin

de la escritura)hacia el vaco que la bordea,(el retardo de la lectura)

destruyendo objetivamente la subjetividad: lo no textual. La fotografa y el

texto: la horizontal, la vertical: la forma de una pistola. (Rupture, absence,

emptiness, here reality is woven: (life, death: what is lef in, what is lef

out): the head taking of from the page[the fxation of writing]into the

emptiness that surrounds it,[the delay of reading]objectively destroy-

ing subjectivity: the nontextual. Te photograph and the text: the horizon-

tal, the vertical: the shape of a gun.)

Te collage itself has the schematic shape of a gun: the vertical text under

the image can be seen as the grip and the horizontal photograph as the barrel.

For this reason, the text at the bottom right of the image announces: El percu-

tor ya golpeado y el gatillo humeante como una pipa (Te hammer and trigger

beaten and smoking like a pipe). If the shape of the text and the image makes

a gun, Bretons pipe is the trigger and his head is the barrel. Te text below the

image, adopting a scientifc or technical discourse, gives a convincing expla-

nation of how hair turns gray.

Te title of Bretons book Le rvolver cheveux blancs (:,:; Te revolver

with white hair) refers to a typically surreal image, one that is playfully materi-

alized through Martnezs collage in a manner reminiscent of Dada. Martnez

defetishizes the image of the founder of surrealism, frst by changing its orienta-

tion from horizontal to vertical and then by spacing the relationship between

text and image. As critic Rosalind Krauss states with regard to Dadaist col-

lage, the white space between the letters and the image reamrms their separa-

tion, their formal exclusion, and their rearticulation and reinterpretation on

Fig. 2.

Page from Juan Luis Martnez,

La nueva novela (Santiago:

Ediciones Archivo, 1985),

60, featuring a collage by

Martnez.

183

THE PHOTOGRAPHIC LEGACY OF SURREALISM

184

AYALA

the page." In any event, Martnezs image-poem can be interpreted as both a

homage to Breton as well as a critical intervention. As Dawn Ades notes about

Max Ernst collages, this articulation of the comical and the marvelous is one

of the prominent features of surrealism.' By means of the juxtaposition of text

and image, sense and nonsense, the literary and the scientifc, La nueva novela

embodies the spirit of surrealism.

Martnezs work presents an extended parody of reasoning in which form

and syntax foreground the efect or sensation of truth while denying any

clear meaning. In a seminal essay, the poets Enrique Lihn and Pedro Lastra

state that in La nueva novela, the language makes fragile its criteria of truth

and reality.'" Surrealism as well as nonsense and absurdist literature (both the

works of Lewis Carroll and his photographs of Alice Liddell appear in La nueva

novela) are the antecedents of this procedure. Martnez multiplies the semi-

otic practices (photography, quotes, collages), which, instead of fxing meaning,

trigger unusual and marvelous permutations. La nueva novela hints at the infu-

ence of the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges, given its use of humor and its

conception of writing as a form of reading and quoting. But from a visual point

of view, Rosalind Krausss statement with regard to the French writer Georges

Bataille comes to mind: a production of images that do not decorate, but rather

structure the basic mechanisms of thought.''

As the Chilean critic Valeria de los Ros proposes, photography is a key

to reading La nueva novela, frst and foremost in its use of the positive/nega-

tive doubling of images and collages.' Building on the ideas of scholar Reese

Jenkins, de los Ros argues that Martnez employs photography to actualize the

cultural oppositions between science and art, positivism and romanticism that

emerged at the invention of photography in the nineteenth century.'` From

these observations, we can likewise conclude that La nueva novela tries to solve

the contradiction between these procedures by means of the surrealist marvel-

ous, which confates the real and the imaginary, the quotidian and the fantastic.

Ral Zuritas Purgatorio: Te Fragmented Self and Collective Fantasy

Troughout the :8os, Ral Zuritas Purgatorio (:,) became one of Chiles

most highly regarded literary works. Te book stands out at frst glance: the

front cover presents a close-up photograph of an unidentifable body part, per-

haps an opening in the skin, an eye and brow, a beard, the female pudenda, or

some uncanny hybrid of these (fg. ,). In an interview conducted at the time

of the books publication, the author stated that the photograph portrays the

scar of a self-inficted wound. Interestingly, Zuritas act of violence was neither

fully improvised nor well planned, neither a public performance (there were no

185

THE PHOTOGRAPHIC LEGACY OF SURREALISM

Fig. 3.

Front and back cover of Ral

Zurita, Purgatorio (Santiago:

Editorial Universitaria, 1979),

featuring a photograph by

Zurita.

cameras recording the event itself) nor truly private (a photograph taken later,

of the scar, appears on a book cover). Zurita described the event this way: It

was absolutely conscious and premeditated . . . I locked myself in the bathroom,

I put an iron in the fames of the hot water heater until it was red and I put it

to my lef cheek. Afer thatI dont know why, and maybe a psychiatrist could

explain it wellI felt that that action reunited me a little. I was in a state of total

dissociation. Afer a while I realized that if I were to write something, it had to

start from this.' Te same image appears on the back cover, with the accom-

panying text: Ahora Zurita / que rapado y quemado / te hace el arte // Santiago

de Chile / :,. (Now Zurita / shaved and burned / art makes you // Santiago

de Chile / :,.)

Here, we have a series of elements that are further developed in Zuritas

work. On the one hand, there is the literary construction of a subject in a state

of psychic fragmentation. Te self-inficted wound could be a way to over-

come this fragmentation through painful bodily presence. If the cut on the skin

is to be understood as a form of writing, it is marked through presence. In

the same fashion, the photograph of the scar functions as a testimony of that

186

AYALA

presence. On the other hand, the act of cutting, the wound, and the photo-

graph are supplemented twice with texts: frst, the interviewexcluded from

Purgatorio yet an important key to its interpretationand then the text on

the back cover. Both resignify the psychic sufering and the wound in terms

of art and writing. In this way, Zurita tries to blur the boundaries between

art and life, the body and text, and the subject and the Others gaze. Te rest

of the photographs in the book exhibit this same quality: they have an indexi-

cal function (in Charles Sanders Peirces terms) but are supplemented with a

text. For example, a spread at the beginning of the volume shows a low-quality

reproduction of the authors face that resembles a photocopy of an ID photo,

but on the opposite page (fg. ), the text reads: Me llamo Raquel estoy en

el ofcio desde hace varios aos. Me encuentro en la mitad de mi vida. Perd

el camino. (My name is Rachel. Ive been on the job for some years now.

Im halfway through my life and Ive lost my way.)' Tis text repurposes the

photograph from its testimonial function: although the subject of the image

Fig. 4.

Pages from Ral Zurita,

Purgatorio (Santiago: Editorial

Universitaria, 1979), 1213.

187

THE PHOTOGRAPHIC LEGACY OF SURREALISM

is the author, the text is in the frst-person singular and indicates a diferent

name and gender (Rachel) from that of the author (Ral Zurita). Te text here

also makes an allusion to the famous frst tercet of Dantes Divine Comedy:

Midway in the journey of our life / I came to myself in a dark wood, / for the

straight way was lost.'

As is evident from the title of Zuritas book, Dantes work is the primary

intertextual link to Purgatorio, both as a narrative of ascension and as a source

of Catholic fgures and motifs. At the bottom of this spread of Purgatorio, we

read in Latin, Ego sum qui sum (I am who I am), a tautological quotation

from the Bible (Exodus ,::) in which God declares the certainty of his exis-

tence and his power. Te line appears in a diferent font from the rest of the text

and is perfectly divided across the pages. Te image of the author and the two

texts combine a fragmentation of the self and the fantasy of a godlike certainty

an excessive certainty acquired only through the text.

Te photographic representation of the authors wound implies an intersub-

jective gaze. In readings that aim to historicize Zuritas work, this articulation

of a collapsed subjectivity is related to the repressed collective subject of the

nation of Chile under the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet, which

lasted from :,, to :8. In Margins and Institutions, Nelly Richard asserts that,

during this time in Chile, performance artists used the body to articulate the

private and public spheres of life. Zurita used bodily pain in particular as the

element of suture between the subjective and the collective.'' Pain, conceived as

the traumatic presence of the body, connects the identifcation of the artist with

collective sufering. As Richard states, Self-punishment merges with an us in

that it is both redeemer and redeemed in a tradition of communal sacrifce, or

the ritual exorcism of violence.'"

Another way of relating the subject and society is through the fantasy and

collective redemption of poetic text, as exemplifed by the numerous images

of the Chilean landscape in Zuritas work. In these images, the reader is con-

fronted with what the critic Walter Benjamin, referring to surrealist practices,

termed the profane illumination of the poetic image based on material.'' In

Purgatorio, diferent spaces interact: on one side are the virtual spaces of math-

ematics, text, and dreams; on the other, the real spaces of Chilean geography

and the printed page. Trough Zuritas text, various topologiesthe psychic,

the collective, the geographic, and the politicalcollapse in on one another. In

this new topology, dreams and reality communicate, the marvelous turns real,

life and work coincide, and language and context resignify each other. Tis is

exemplifed in Para Atacama del desierto (For Atacama of the Desert), named

for a ooo-mile strip of land located in the north of Chile that is said to be the

driest desert in the world:

188

AYALA

For Atacama of the Desert

i. Let us look then at the Atacama Desert

ii. Let us look at our loneliness in the desert.

So that desolate before these shadows the landscape becomes a cross

stretched out over Chile and the loneliness of my shadow then sees the

redeeming of the other shadows: My own Redemption in the Desert.

iii. Who would then credit the redeeming of my shadow

iv. Who would speak of the deserts loneliness

So that my shadow begins to touch your shadow and your shadow that

other shadow and so on until all Chile is just one shadow with open arms:

one long shadow crowned with thorns

v. Ten the Cross will be merely my shadow opening its arms

vi. We will then be the Deserts Crown of Torns

vii. Ten nailed shadow to shadow like a Cross stretched out over Chile we

will have seen forever the Solitary Expiring of the Atacama Desert. "

In this section of poems about the Atacama Desertas in the section reas

verdes (Green areas) of Purgatorio, where a Cartesian space overlaps with the

pastoral landscape of cows out to pasture, creating a sort of virtual realitythe

poet places a new or illusory reality of delirium or messianic delusion upon the

image of the desert. Here, imagination and reality merge and the text occupies

the locus of the unconscious in a gesture reminiscent of Bretons surrealism but

with the added space for collective redemption.

Claudio Bertoni and the Desire of Everyday Life

Claudio Bertoni is a poet, photographer, and visual artist who has succeeded

in incorporating these diferent media into coherent works. Among Chilean

poets, Bertoni has won a unique and numerous following as a former hippie,

a Buddhism specialist, and a connoisseur of soul and jazz music. In his

ofen transparently autobiographical poetry, Bertoni refers to himself in a

189

THE PHOTOGRAPHIC LEGACY OF SURREALISM

self-deprecating manner refecting everyday speech. His writing resembles a

diary, wherein he registers feeting thoughts and details of his private life, with

its many contretemps, regardless of how dull, absurd, silly, or bizarre they may

seem. Elements of mass culture, such as his favorite musical genres and TV

programs, are mixed with traditionally serious subjects such as God, illness,

death, and loneliness.

From the start, sex and desire have been important themes of Bertonis work,

particularly the fugitive desire and sexual attraction caused by aleatory encoun-

ters in the city. As Benjamin observes, in analyzing the French poet Charles

Baudelaire, Te delight of the city dweller is not so much love at frst sight as

love at last sight.' In the shocking moment of the visual encounter, the urban

dweller falls in love with someone he is never going to see again. Te fneur,

who relishes in the anonymity of the chance encounter, fnds an answer to his

desires in the city. Taken up by the surrealists, this motif was labeled objective

chance and has an important place in poet Louis Aragons Le paysan de Paris

(::o; Te Paris Peasant, :) and Bretons Nadja (::8), in which an enigmatic

anxiety is perceived in the people and objects found in the city. Bertoni takes

the Baudelairian and surrealist principle of the masculine gaze to its mundane

extremes. He looks for and fnds attractive women everywhere in the city: on

sidewalks and buses, in queues, cafs, and shops (fg. ,). Te urban space is

organized through women as well as time. Bertoni embodies the anxiety of

male desire in the modern city.

Te famous line by Pablo Neruda, Love is so short; forgetting, so long,

from Poema :o, was rewritten by Bertoni in a short poem titled Una vez

ms (Once more), which reads, Te miniskirt is so short; forgetting, so long.

Te sublimity of love and the complexity of mourning the object of desire are

reduced to the shock that the miniskirtand the fragmented female body

provokes in the poetic subject. Te miniskirt is an object of desire as wellnot

as something lost, but rather as an anonymous, ephemeral object that was never

possessed in the frst place. Te diferences between Neruda and Bertoni lie in

their tone (the former solemn and the latter playful) and their positioning of

the poetic subject. In Veinte poemas de amor y una cancin desesperada (::;

Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair, :o), Neruda embodies the romantic

subject prior to his avant-garde period, while in Una vez ms, Bertoni uses

humor: he references a common urban experience in which daily life is sud-

denly disrupted by the sight of an anonymous and attractive woman.

One remarkable feature of Bertonis poetry is its metonymic articulation

a predominant trope in his writingthrough which chance and desire inter-

sect in the urban landscape. Te poetic persona does not have to possess the

object of desire but only pass close enough to obtain a certain satisfaction. For

190

AYALA

example, in the text Algo es algo, (Somethings better than nothing), Bertoni

writes, I take a bus / and I see a woman / who will never be mine // I sit behind

her / and her hair caresses / my fngers.` Desire is fulflled, or at least subli-

mated, by an accidental, unconscious, and light caress of the womans haira

fragment of her body, fitting across the fngers of the poetic subject. Many of

Bertonis poems are so short that they could have been jotted down at the same

spot were the experiences took place, as a literary snapshot of the moment. Te

model for this writing is not only the diary but also photography.

Photographs of women caught in the street by chance supplement many of

Bertonis poems. A collection of these photographs taken in the :,os and :8os

was published recently in the book Chilenas (:oo). As a veteran street pho-

tographer, Bertoni carries his camera hanging around his neck, and when the

occasion arises, he has to point and shoot the photograph in an instant. Ofen

speed is more important than perfect composition in registering the passing

subject. Some of these photos exhibit an awkward framing, and the position of

the photographer does not always seem to occupy the most privileged point of

view (fgs. ,,).

Te act of taking a picture is ofen homologous to a violent act of possession,

in which the camera takes the place of a weapon or phallus. To photograph

Fig. 5.

Claudio Bertoni (Chilean,

b.1946).

Photograph from Claudio

Bertoni, Chilenas (Santiago:

Ocho Libros, 2009), 79.

Fig. 6.

Claudio Bertoni (Chilean,

b.1946).

Photograph from Claudio

Bertoni, Chilenas (Santiago:

Ocho Libros, 2009), 78.

Fig. 7.

Claudio Bertoni (Chilean,

b.1946).

Photograph from Claudio

Bertoni, Chilenas (Santiago:

Ocho Libros, 2009), 80.

191

THE PHOTOGRAPHIC LEGACY OF SURREALISM

attractive women in the street without their consent could be considered an

act of crass male aggression. In spite of the masculine impulse underlying his

project, Bertoni was a shy photographer; sometimes he did not even dare to

look through the viewfnder to focus and frame. Ofen, he seems to have taken

the picture without raising the camera up to eye level; the camera remained on

his chest while he shot the photograph, one could say, from the heart. Tese

pictures are not completely conscious in their focus and framing, and thus the

chance encounter in the city is reinforced by a chance snapshot that questions

the power of the male gaze.

It seems that blurred, unbalanced, and unfocused compositions enact the

transgressive form of desire itself: blind and undiscerning, brief in its explosion

but inexhaustible. Nevertheless, these unconscious, or half-conscious, snap-

shots are not violent in their representation of the fneurs surprise encounter

with desire in the urban landscape. Essentially, the instability of composition in

these snapshots undoes the violence of the masculine gaze by highlighting the

male subjects lack of intervention or agency. In this way, Bertoni reinterprets

surrealist automatism by inscribing desire in the work of art without making it a

romantic fetish. While avoiding the the creation of suggestive imagery through

the operations of chance, he remains close to the surrealist movement by

192

AYALA

recording feeting desire. In Bertonis work, both poetry and photographs are

elements of a project based on chance encounters with the objects of desire.

Bertoni recognizes this desire as a lack, and its literary and visual representation

is likewise always marked by absence.

Martnez, Zurita, and Bertoni use photography, an essentially technical

medium, to complement the romantic aspects of literary surrealism that ide-

alize the Other and that ofer synthesis among diferent elements. Martnezs

literary and visual games combine science and poetry, or knowledge and non-

senseopening marvelous and humorous interstices in the prosaic. In Zurita,

photographs with a referential function that combine life and art resignify the

psychic pain of the poets identity in crisis. Similarly, the geographical space

of fantasy provides the locus of collective redemption. Finally, in Bertoni, the

desire of the city dweller is set free through photography and poetry. Te male

gaze fnds diferent ways to compensate its desire, either by a metonymic pres-

ence or a sudden snapshot. Martnez, Zurita, and Bertoni, through the media-

tion of photography, open the literary to visuality, creating unclassifable works,

and in this way, revitalizing the legacy of surrealism in the Chilean neo-avant-

garde poetry of the seventies and eighties.

Notes

Tis article is part of the research project Fondecyt number :::oo:o, supported

by CONICYT, Chile. All translations are my own, unless otherwise noted.

:. Troughout Latin America, a handful of literary and artistic journals were devel-

oped as a way to experiment at a formal level, to criticize the cultural feld, and to

modernize through both the incorporation and reconfguration of metropolitan

procedures and techniques. Among others magazines, it is necessary to mention

Martn Fierro (Buenos Aires, :::,), Amauta (Lima, ::o,:), Contemporneos

(Mexico, ::8,:), Revista de avance (Havana, ::,,o), Mandrgora (Santiago,

:,8,).

:. Dawn Ades, Photography and the Surrealist Text, in Rosalind Krauss and Jane

Livingston, eds., LAmour Fou: Photography and Surrealism (Washington, D.C.:

Corcoran Galley of Art, :8,), :,,8.

,. Rosalind Krauss, Te Photographic Conditions of Surrealism, in idem, Te

Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge: MIT

Press, :8o), 8,::8.

. Ian Walker, City Gorged with Dreams: Surrealism and Documentary Photography

in Interwar Paris (Manchester: Manchester Univ. Press, :oo:).

,. David Bate, Photography and Surrealism: Sexuality, Colonialism and Social

Dissent (London: I.B. Taurus, :oo).

o. Juan Luis Martnez, La nueva novela (Santiago: Editiones Archivo, :,,).

193

THE PHOTOGRAPHIC LEGACY OF SURREALISM

,. Martnez, La nueva novela, oo.

8. Krauss, Photographic Conditions, :oo,.

. Dawn Ades, Photomontage (London: Tames & Hudson, :8), ::o.

:o. Enrique Lihn and Pedro Lastra, Seales de ruta de Juan Luis Martnez (Santiago:

Ediciones Archivo, :8,), :o.

::. Rosalind Krauss, Corpus Delicti, October ,, (:8,): ,:,:, ,,.

::. Valeria de los Ros, La fotografa como clave de lectura de La nueva novela,

Estudios flolgicos (:oo): ,o.

:,. De los Ros, Fotografa, ,,.

:. Ral Zurita, Ral Zurita: Abrir los ojos, mirar hacia el cielo, in Juan Andrs

Pia, Conversaciones con la poesa Chilena: Nicanor Parra, Eduardo Anguita,

Gonzalo Rojas, Enrique Lihn, Oscar Hahn, Ral Zurita (Santiago: Pehun, :o),

:,:,,, :o.

:,. Ral Zurita, Purgatorio (Santiago: Editorial Universitaria, :,), :::,. Ral

Zurita, Purgatorio, :,o:,,, trans. Jeremy Jacobson (Pittsburgh: Latin American

Literary Review Press, :8,), ::.

:o. Tis translation by Robert Hollander of Dantes La divina commedia (ca. :,o8::)

is taken from the Princeton Dante Project, http://etcweb.princeton.edu/dante/

(:o May :o:o). Te Divine Comedy is divided into three major sections: Inferno,

Purgatory, and Paradise.

:,. Nelly Richard, Margins and Institutions (Melbourne: Art & Text, :8o), o,.

:8. Richard, Margins and Institutions, oo, o8

:. Walter Benjamin, Surrealism: Te Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia,

in Selected Writings, vol. :, ::,:, ed. Michael W. Jennings et al., trans.

Rodney Livinstones et al. (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap, :), ::,.

:o. Zurita, Purgatorio, :,o:,,, o:.

::. Walter Benjamin, Te Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire, in idem,

Selected Writings, ed. Michael W. Jennings, vol. , :8:o, trans. Edmund

Jephcott et al., ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge, Mass.:

Belknap, :oo:), :,.

::. Claudio Bertoni, Jvenes buenas mozas (Santiago: Cuarto Propio, :oo:), ,o.

:,. Bertoni, Jvenes buenas mozas, :.

:. Claudio Bertoni, Chilenas (Santiago: Ocho Libros, :oo).

:,. Krauss, Corpus Delicti, ,.

Getty Research Institute

Issues & Debates

Edited by DAWN ADES, RITA EDER, and GRACIELA SPERANZA

SURREALISM IN

LATIN AMERICA

VIVSIMO MUERTO

THE GETTY RESEARCH INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS PROGRAM

Tomas W. Ga ehtgens, Director, Getty Research Institute

Gail Feigenbaum, Associate Director

:o:o J. Paul Getty Trust

Published by the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Getty Publications

::oo Getty Center Drive, Suite ,oo

Los Angeles, CA oo-:o8:

www.getty.edu/publications

Tobi Kaplan, Lauren Edson, John Hicks, and Laura Santiago, Manuscript Editors

Tobi Kaplan, Production Editor

Catherine Lorenz, Designer

Amita Molloy, Production Coordinator

Diane Franco, Typesetter

Stuart Smith, Series Designer

Type composed in Minion and Trade Gothic

Printed in TK through TK

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

[TK]

Front cover: [caption TK]

Back cover: [caption TK]

Frontispiece: Francis Als (Belgian, b. :,), Hopscotch (Rayuela), :o:o, preparatory sketch for an intervention

in the exhibition Domin canbal (PAC MURCIA, :o:o), Sala Vernicas, Murcia, Spain.

Tis volume evolved from Vivsimo Muerto: Debates on Surrealism in Latin America, a symposium held at

the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, :,:o June :o:o.

[Frontispiece]

Francis Als (Belgian,

b.1959). Hopscotch

(Rayuela), 2010, preparatory

sketch for an intervention in

the exhibition Domin canbal

(PAC MURCIA, 2010), Sala

Vernicas, Murcia, Spain.

Collection of the artist.

vi Acknowledgments

1 Introduction

DAWN ADES, RITA EDER, AND GRACIELA SPERANZA

Part One. Surrealist Love Letters:

The Art and Poetry of Csar Moro

00 We Who Have neither Church nor Country:

Csar Moro and Surrealism

DAWN ADES

00 Semiotics of the Body and the Passions in

Csar Moros Love Letters and Poems

YOLANDA WESTPHALEN

00 Making the Stone Speak: Csar Moro and the Object

KENT DICKSON

Part Two. Surrealist Encounters in the New World:

Pre-Columbian and Northwest Coast Art

00 Benjamin Pret and Paul Westheim:

Surrealism and Other Genealogies in the Land of the Aztecs

RITA EDER

00 Anthropology in the Journals Dyn and El hijo prdigo:

A Comparative Analysis of Surrealist Inspiration

DANIEL GARZA USABIAGA

00 Wolfgang Paalen: Te Totem as Sphinx

ANDREAS NEUFERT

Part Three. Revisiting the Surrealism Revolution:

Ideology and Action

000 Andr Bretons Anthology of Freedom:

Te Contagious Power of Revolt

MARIA CLARA BERNAL

000 My Goddesses and My Monsters:

Maria Martins and Surrealism in the s

TERRI GEIS

CONTENTS

vi

Part Four. The Surrealism Effect: Legacies and Reception

in Art, Literature, and Politics

000 A Note Concerning Causality: Julio Cortzar and Surrealism

GAVIN PARKINSON

000 Te Photographic Legacy of Surrealism in

Late-Twentieth-Century Chilean Poetry

MATAS AYALA

000 Wanderers: Surrealism and Contemporary Latin American Art

and Fiction

GRACIELA SPERANZA

000 Biographical Notes on Contributors

00 Illustration Credits

000 Index

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Lesson Plan in Grade 7 PoemDocument2 pagesLesson Plan in Grade 7 PoemMire-chan Bacon75% (4)

- Yahuwshua Is Not Jesus - Book of DisclosureDocument24 pagesYahuwshua Is Not Jesus - Book of Disclosuretotalise80% (5)

- Davis HurstonDocument19 pagesDavis HurstonDanica StojanovicNo ratings yet

- Gopal GovindDocument3 pagesGopal Govindvrohit308No ratings yet

- Islamabad Academy MZD: Pre-Board Test 2016Document2 pagesIslamabad Academy MZD: Pre-Board Test 2016Prince ArsalNo ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension Strategies For Students With Autism - A GuidDocument93 pagesReading Comprehension Strategies For Students With Autism - A GuidAl OyNo ratings yet

- 04 - The Rise of English Novel - Richardson and Fielding Summing UpDocument2 pages04 - The Rise of English Novel - Richardson and Fielding Summing UpArminParvinNo ratings yet

- The Affliction of MargaretDocument2 pagesThe Affliction of Margaretmik catNo ratings yet

- Lecture by HH Jayapataka Swami MaharajDocument7 pagesLecture by HH Jayapataka Swami MaharajRanjani Gopika Devi DasiNo ratings yet

- Commas and ClausesDocument5 pagesCommas and ClausescinziaagazziNo ratings yet

- A.K. RamanujanDocument2 pagesA.K. RamanujanLaiba Aarzoo100% (2)

- Fahrenheit 451 SummaryDocument46 pagesFahrenheit 451 SummaryLamyaa Amshouf0% (1)

- When I Look at A Strawberry, I Think of A Tongue - Édouard LevéDocument4 pagesWhen I Look at A Strawberry, I Think of A Tongue - Édouard LevéPaul HoulihanNo ratings yet

- Reference Image Text in German and Australian Ad PostersDocument15 pagesReference Image Text in German and Australian Ad PostersCynthia LohNo ratings yet

- Brahma Satyam Jagat MithyADocument7 pagesBrahma Satyam Jagat MithyASundararamanK100% (1)

- SoundArt Neuhaus PDFDocument1 pageSoundArt Neuhaus PDFJosé PereiraNo ratings yet

- Caitanya CandramrtaDocument22 pagesCaitanya CandramrtaMaria Celeste Camargo CasemiroNo ratings yet

- RNSE2Document7 pagesRNSE2George JeniferNo ratings yet

- Essay AssignmentDocument5 pagesEssay Assignmentapi-280539793No ratings yet

- Shota Rustaveli: The Man in The Panther's SkinDocument22 pagesShota Rustaveli: The Man in The Panther's SkintornikeNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of Masque of The Red DeathDocument1 pageCritical Analysis of Masque of The Red DeathCharity Anne Camille PenalozaNo ratings yet

- The Evidence For Women Priests in MandaeismDocument14 pagesThe Evidence For Women Priests in MandaeismisrarandaNo ratings yet

- Carmel LibraryDocument8 pagesCarmel Libraryapi-280660962No ratings yet

- Comparative Example EssayDocument2 pagesComparative Example EssayStephanieNo ratings yet

- InSpectres UnSpeakableDocument3 pagesInSpectres UnSpeakableTim RandlesNo ratings yet

- Shiv Tandav Stotra - Shiv Tandav Stotra - Shiv Tandav Stotra - Shiv Tandav Stotra - िशवताǷवˑोũम्Document9 pagesShiv Tandav Stotra - Shiv Tandav Stotra - Shiv Tandav Stotra - Shiv Tandav Stotra - िशवताǷवˑोũम्superangel2000in913No ratings yet

- IGNOU Lady LazarusDocument17 pagesIGNOU Lady LazarusAisha RahatNo ratings yet

- Creative Writing ModuleDocument230 pagesCreative Writing ModuleEMMAN CLARK NAPARANNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of A Well Formulated Research ProblemDocument3 pagesCharacteristics of A Well Formulated Research ProblemSpandan AdhikariNo ratings yet

- Ahlct 002Document10 pagesAhlct 002marija9996143No ratings yet