Professional Documents

Culture Documents

House-Tree-Person Projective Technique A Validation of Its Use in Occupational Therapy

Uploaded by

rspecuOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

House-Tree-Person Projective Technique A Validation of Its Use in Occupational Therapy

Uploaded by

rspecuCopyright:

Available Formats

CJOT Vol. 53 No.

4

House-Tree-Person Projective Technique: A

'a' ration of its Use in Occupational Th *a ^ y

by Helen Polatajko and Ethel Kaiserman

The acute care psychiatric setting

requires that the occupational thera-

pist comes to an early decision re-

garding client treatment. In order to

do this, the occupational therapist

needs to have available efficient, re-

liable and valid evaluation tools.

Projective techniques have often

been used in occupational therapy

for evaluation. Symbols are felt to

uncover the ideas and feelings of an

individual. Rosenfeld (1982) wrote

that projective tests help in the es-

tablishment of the individual's

Helen Polatajko, PhD., OT(C), is an Associate

Professor, in the Department of Occupational

Therapy, Faculty of Applied Health Sciences,

cross appointment to Department of Educa-

tional Psychology Faculty of Education,

University of Western Ontario, London,

Ontario.

Ethel Kaiserman, B.O.T., OT(C), is an

Occupational Therapist, with Community

Occupational Therapy Associates, Toronto,

Ontario. At the time of the study she was the

Senior Occupational Therapist, Psychiatry,

Occupational Therapy Services, University

Hospital, London, Ontario.

present concept of self and environ-

ment as well as his emotional self:

It has been considered that the ex-

pression of ideas and feelings which

are not completely understood by

the individual or currently accept-

able to the individual is possible

The H.T.P. data were

being used to develop an

O. T. problem list and to

select O. T. treatment

strategies.

through the use of symbols (Mosey,

196 8). Unfortunately, at the present

time, none of the projective tests

developed specifically for the use in

occupational therapy, are standard-

ized or well researched.

The House-Tree-Person Projec-

tive Technique (H-T-P) provides an

instrument with a well-standardized

system of administration. This in-

strument was developed in 1948 by

Buck, a psychologist, primarily as a

test of intelligence. However, as

more exact tests of intelligence were

developed, it ceased to be used for

this purpose. Rather, its secondary

use, the identification of personality

traits and factors, predominated. In

a formalized manner, the client is

asked to draw first a house, then a

tree and finally a person. This is

followed by the `post-drawing inter-

rogation' consisting of 6 4 specific

questions and a follow-up of any

leads resulting from the answers to

these questions. The drawings, to-

gether with their responses to the

questions, are then interpreted to

provide data concerning the per-

ceived developmental, traumatic or

environmental problems of the

client. Jones (1981) has provided a

manual to guide these interpreta-

tions.

The H-T-P has been in use by

occupational therapists at University

Hospital, London, Ontario, as part

of an assessment procedure with

October/Octobre 1986

197

CJOT Vol. 53 No. 4

acute psychiatric clients. The thera-

pists felt that the information col-

lected had implications for occupa-

tional therapy treatment. Thus,

H-T-P data were being used to

develop an occupational therapy

problem list and to select occupa-

tional therapy treatment strategies.

Subjectively, the therapists found

the use of the H-T-P to be an enjoy-

able and beneficial process giving

them greater insight into their

clients' problems and facilitating

rapport. It was also felt to provide

a forum for the establishment of a

consensus between therapist and

client regarding further assessment

and the treatment program. Howev-

er, the literature provided no empir-

ical evidence to support the use of

the H-T-P in this manner. The pur-

pose of the study was to investigate

the validity of the H-T-P in identify-

ing functional problems.

Literature Review

Initially, much of the work on the

H-T-P dealt with its use as a test of

intelligence. However, as indicated

above, with the advent of more valid

intelligence tests, its use and subse-

quently the research in this area

decreased a good deal (Kuhlman &

Bieliauskas, 1976; Kline & Svaste,

1981). This literature is not of inter-

est here and will not be discussed.

Of interest here is the use of the

H-T-P as a method of identifying

stress factors and personality char-

acteristics and its use in psychiatric

occupational therapy.

As with many projective tech-

niques, the H-T-P received its impe-

tus from psychoanalytical theory

and evolved from empiricism and

practical clinical observations

(Robin & Haworth, 1971). Symboli-

cally potent concepts such as house,

tree and person are thought to be

saturated with the emotional and

ideational experiences associated

with the personality's development,

the drawing of these images compel-

ling projection on the part of the

drawer (Hammer, 1978). In regard

to his choice of the specific items,

Buck (1981) considered that the

house, tree and person: a) were items

familiar to all; b) were more will-

ingly accepted than other items, as

objects for drawing by subjects of all

ages; and c) stimulated more frank

and free verbalization than did other

items.

As Hammer (1978) describes, the

house, as a dwelling place, has been

found to arouse within the subject

associations concerning home life

and intra-familial relationships. The

drawing of the house may reflect the

subject's domestic situation in rela-

tionship to his spouse or the child-

hood relationship to parental figures

may still be apparent as residual

attitudes. The drawing of the tree

appears to reflect the subject's relati-

vely deeper and more unconscious

feelings about himself, whereas the

drawn person becomes the vehicle

for conveying the subject's closer-to-

conscious view of himself and his

relationship with his environment.

In this manner, a picture of the

conflicts and defenses as set in the

hierarchy of the subject's personality

structure is provided.

The research evidence to support

the validity and reliability of the

H-T-P in its use in the identification

of personality factors or stress factors

is scant and can be easily criticized.

Nevertheless, based on research

available at the time the last review-

er of the H-T-P for the Mental Mea-

surements Year Book concluded that

the H-T-P is a valuable tool:

The H-T-P is now, and no doubt will

continue to be, used as a rewarding

clinical technique in work with both

adults and children. The amount of

meaningful projective data to be

derived from the drawings (and the

inquiry, if used) will depend on the

experience and o rientation of the cli-

nician. The test can serve as a non-

threatening `opener' before more for-

mal testing (Haworth, 1965, p. 436).

It should be noted that this review

is quite old. This is reflective of the

evolution of projectives in general,

i.e., there was a loss of interest in

such tests for a period of time due

to the difficulty encountered in es-

tablishing rigorous evidence of the

reliability and validity of such tests

(Robin and Haworth, 1971).

There have been some studies

concerning the H-T-P in the more

recent past. A number have used the

H-T-P as a measure of change with

a variety of patient populations. For

example, Gording and Match (1968)

reported on a preliminary study

using the techniques of free-hand

figure drawings of a house, tree and

person (H-T-P) to investigate per-

sonality changes in 33 contact lens

wearers. Ernst, Beran, Badashi, Ko-

sovsky and Kleinhauz (1977) used

the H-T-P with elderly people with

a diagnosis of "chronic brain syn-

drome", to investigate the effects of

bi-weekly sensory stimulation and

group therapy over a period of three

months. Perkins and Wagemaker

(1977) administered the H-T-P four

times to a chronic schizophrenic un-

dergoing hemodialysis. Platzer

(1976) used the H-T-P in pre/post

test fashion with 40 subjects with

deficits in gross-motor skills and

self-concept, randomly assigned to

experimental and control groups to

determine program effectiveness.

All of the above investigators

reported changes due to treatment,

having confidence in the test-retest

reliability of the H-T-P. However,

these data cannot clearly be inter-

preted as support for the instru-

ment's test-retest reliability. Such

data is difficult to obtain due to the

nature of both the instrument and

its intended use (Haworth, 1965).

A number of studies have used the

H-T-P to identify differences in per-

sonality between various groups.

Wildman, Wildman and Smith

(1967) asked hospital ward person-

nel to select 30 extroverted patients

and 30 introverted patients. Both

groups were asked to draw same sex

drawings according to H-T-P test

instructions. Extroverts did not make

significantly larger drawings than

introverts. Even when extreme cases

of expansiveness or constriction were

used, the predictions of the H-T-P

were only slightly above chance.

Davis and Hoopes (1976) com-

pared the H-T-P drawings of a

matched sample of 80 deaf and 80

hearing, 7-10 year olds to assess

differences related to the handicap,

and the capacity of the H-T-P to

distinguish between children rated

by their teachers as poorly adjusted

and those rated well adjusted. No

differences were found between deaf

and hearing children in the drawing

198

October/Octobre 1986

CJOT Vol. 53 No. 4

of the ear or mouth of the human

figure, although there were signifi-

cant differences in the drawing of the

branch structure of the tree. Also, no

differences were found in the num-

bers of indicators of disturbance be-

tween the drawings of the subjects

rated as more and less well adjusted.

Kuhlman and Bieliauskas (1976)

administered the H-T-P to 30 black

and 30 white adolescents, matched

for sex, age, intelligence and socio-

economic level. No significant dif-

ferences were found between the two

groups on either the H-T-P, IQ mea-

sures or the adjustment ratings.

Hoover (1978) attempted to con-

struct a composite personality profile

for skydivers. Eighteen active ' sky-

divers (median age 24-6 years), were

administered the Rorschach,'' the

Hand, the H-T-P and Draw-A=Per-

son tests. No statistically significant

differences were found between the

skydivers and a matched group of

controls.

Gasparrini, Shealy and Walters

(1980) administered the H-T-P to 17

right hemisphere brain-damaged

patients, 19 left hemisphere brain-

damaged patients and 23 non brain-

damaged medical patients. Statisti-

cal analyses revealed significant

differences between groups in size

and spatial placement of drawings.

Blain, Bergner, Lewis and Gold-

stein (1981) conducted a study to

determine whether the H-T-P might

be used as a means to identify physi-

cally abused children. Protocols of

32 abused children, 32 nonabused

but disturbed children and 45 ap-

parently well-adjusted children. (ages

5-12 years) were examined for the

presence of 15 objectively scorable

items that emerged as good potential

discriminators from an earlier pilot

study. Results of several statistical

analyses indicate that (1) items taken

individually discriminated strongly

between abused and well-adjusted

subjects, but not between abused

and non-abused but disturbed sub-

jects; and (2) the 6 most discrimi-

nating individual items, discrimi-

nated reasonably well between

abused subjects and both of the

other groups.

In the six studies above, the inves-

tigators assumed differences be-

tween the groups being contrasted.

Three of the studies found some

differences (Davis et al. 1975;

Gasparrini et al. 1980; and Blain et

al. 1981). In all three studies the

groups being contrasted were credi-

bly different in some way, thus one

could assume the findings to support

the H-T-P as a valid indicator of

personality factors. However, it must

be remembered that unless there are

other external indicators of such dif-

ferences, the findings remain equiv-

ocal.

Similarly, for the studies that

failed to show differences between

groups it cannot be determined,

from these studies, if differences did

indeed exist or if the findings were

valid.

In some instances the

H. T.P. missed problems

while in others it

identified unique

problems not noted by

nursing or O. T.

Still other studies used the H-T-P

to investigate the characteristics of

a specific population. Doorbar

(1967) used the Wechsler Adult In-

telligence Scale, the Thematic Ap-

perception Test (TAT) and the

H-T-P with 34 transexuals.

Tropauer, Franz and Dilgard (1970)

studied 20 children with cystic fibro-

sis and 23 mothers of such children

using psychiatric interviews and the

H-T-P. Ullman, Moore and Reidy

(1977) compared the performance of

10 adult subjects with chronic atopic

eczema with matched controls on the

MMPI, H-T-P, selected TAT cards

and an open-ended psychiatric in-

terview. Seligman (1979) examined

personality and cognitive charac-

teristics of black foster children using

the Bender Gestalt Test, the H-T-P,

the Wide Range Achievement Test,

the Rorschach, a specially designed

sentence completion inventory, the

Weschler Intelligence Test and an

extensive interview.

These studies indicate the confi-

dence of their investigators in the

H-T-P's ability to assist in the identi-

fication of characteristics. However,

they do not substantiate this, partic-

ularly since these studies used the

H-T-P in conjunction with a number

of other instruments and no clear

indication is given of the relative

contribution of the individual tests

or the correlation between the tests.

Only a few studies looked at the

identification of stress factors using

the H-T-P. Cooper and Caston

(1969) studied the size of human

figure drawings before and after

stress, (the stress being the an-

nouncement of impending heart sur-

gery). They found a trend for post-

stress drawings to be larger than

pre-test drawings. Peyru and De

Pastrana-Borrero (1977) proposed a

psychotherapeutic method centred

on the evaluation of changes in the

patients central oedipal conflict.

They used a battery of psychological

tests administered at regular inter-

vals during the course of therapy;

the H-T-P, the Bender-Gestalt Test,

the Rorshach and the Phillipson

Test, to identify stress in the form

of a focal oedipal conflict.

Finally one study was found which

looked at the significance of a partic-

ular symbol. Devore and Fryrear

(1976) compared the H-T-P draw-

ings of 1,844 juvenile delinquents

and a sample of the adolescents who

drew the tree with a hole or scar to

76 adolescents who drew a tree with

no hole or scar. The two groups were

compared with respect to 22 vari-

ables, including age, sex, urban or

rural residence, total number of si-

blings, reading placement and 8

MMPI scales. The two groups dif-

fered significantly on two variables:

IQ and the mania scale of the

MMPI. Subjects who drew a tree

with a hole were significantly more

intelligent and scored lower on the

mania scale.

As is evident from the above liter-

ature, the summary of the H-T-P

literature by Haworth in 1965 still

applies. The studies that exist have

a number of methodological flaws,

many of which are inherent to the

investigation of projective tech-

niques. Consequently, little or no

external validation exists for charac-

teristics or problems identified by the

October/Octobre 1986

199

CJOT Vol. 53 No. 4

H-T-P. This is necessary before the

instrument can be considered valid.

It was the intent of this study to

examine problems identified by the

H-T-P against some external criteria.

Method

The purpose of this study was to

determine if the H-T-P could validly

and efficiently identify a problem list

for occupational therapy treatment.

In order to do this, a comparative

study using blinded procedures was

carried out.

Sample:

All the clients referred to occupa-

tional therapy between September,

1983 and April, 1984, were consid-

ered for the study. Criteria for

inclusion were: (1) admission to the

psychiatric unit at University Hospi-

tal in London; (2) referral to

occupational therapy; and (3) signed

informed consent. Criteria for exclu-

sion were: (1) acute psychosis; (2)

second admission during the tenure

of the study; (3) research officer's

vacation schedule precluding testing

at designated time for specific

clients; (4) marked motor impair-

ment.

The resulting sample consisted of

40 clients, 10 males, 30 females, be-

tween the ages of 17 and 73 (X =

37.68; SD = 15.42) with a variety

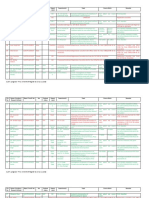

of occupations (see Table 1). The

average length of stay was 4 to 5

weeks (X = 34.68 days; SD =

17.14). The number of admissions

ranged from 1 10 with this being

the first admission for 15 clients and

the second for nine. The clients suf-

fered from a variety of psychiatric

conditions with depression being the

most frequent psychiatric diagnosis

(see Table 2).

Procedures:

H-T-P: Each subject was adminis-

tered the H-T-P by a trained re-

search officer (RO) within the first

two weeks of referral to occupational

therapy. The H-T-P was adminis-

tered as outlined in Buck's manual

(1981), in any available space in the

occupational therapy department

where there would be no interrup-

tion for the duration of the testing.

All testing was done in the late

afternoon. The testing took approxi-

mately 40 minutes. After the testing,

the RO scored and interpreted the

H-T-P using Jolies' manual (1981).

Finally, the RO generated the H-T-P

problem list using the H-T-P dic-

tionary (see below for description)

to translate the H-T-P terms into

occupational therapy terms. The

H-T-P protocols and the H-T-P

problem lists were kept in a place

where the case occupational thera-

pist did not have access to the results

in order to keep the process blind.

Furthermore, only code numbers

appeared on all protocols.

The RO was a qualified occupa-

tional therapist with experience in

psychiatry. She was trained in the

administration and interpretation of

the H-T-P by the senior occupational

therapist on the unit. The training

proceeded as follows: (1) The RO

familiarized herself with selected

material available on the adminis-

tration and interpretation of the H-

T-P, i.e. Bieliauskas, 1980; Buck,

1981; Hammer, 1981; Jolles, 1981;

Wenck, 1981, and then worked

through these with the senior, iden-

tifying issues and discussing prob-

lems. (2) Subsequently, the RO

watched the senior administer one

test and then both the senior and

the RO were videotaped administer-

ing the H-T-P. These tapes were used

to establish inter-rater agreement.

Each viewed the other's video and

then scored the H-T-P independent-

ly. In total, four H-T-P's were ad-

ministered in this fashion. Once 80%

agreement was achieved, data col-

lection started. Halfway through

data collection inter-rater agreement

was again evaluated in the same

manner described above. In all in-

stances, inter-rater agreement was

above 80% ranging from 81% to

100%.

Occupational Therapy Assessment:

Concurrently, but independently,

the occupational therapist assigned

to the case administered the occupa-

tional therapy assessment to the

client. In all cases the occupational

therapist was one of the two occupa-

tional therapists assigned to the psy-

chiatric unit, one of whom was the

senior mentioned above.

The occupational therapy assess-

ment consisted of three parts: (1)

interview, (2) concrete task (tile tri-

vet), and (3) abstract task (collage).

It should be noted that this was a

dynamic assessment process, i.e., it

did not preclude therapeutic input

200

October/Octobre 1986

..,v u Jt. 2

.. .. :'.5c.am g -s

esn..Josa

...r'CSv_.e,..

.4.n.=j diagnosis

ll.i:.^!l

pV!iK;Yi.`'.oc.

scr,;.zoyped pe1oii;: ^y

major p

grief c.;,._.n

.cr'erie :T_)ersons.lity der

CJOT Vol. 53 No. 4

during the assessment. All parts of

the assessment were administered on

a one-to-one basis in a setting similar

to that in which the H-T-P was ad-

ministered, although in this instance,

this was not always a private space.

The assessment was administered at

various times during the working

day, in four separate sessions lasting

for a total of approximately five

hours.

The interview, based on the Occu-

pational Therapy Services Initial In-

terview was always given first. (N.B.

This document, as other non-

published materials mentioned in

this paper are available from the

authors). This was followed by the

concrete task. In this task, the clients

were told where the tiles were and

asked to choose the color and design

for their trivet. They were then given

the glue and trivet and asked to glue

the tiles onto the trivet. After a

period of at least 24 hours (time for

the glue to dry) they were given

grout so that they could finish their

task. Throughout, discussion be-

tween the occupational therapist and

client centred on the choice of color

and pattern, any difficulties exhibit-

ed, and the relationship of these

difficulties to home and work.

The H.T.P. is an efficient

and useful tool,

particularly if it is

augmented by a work

assessment.

Lastly, the clients were asked to

produce a collage. They were given

the necessary equipment and asked

to pick a theme and pictures that

represented that theme. They were

then asked to cut these pictures out

and glue them on paper in any man-

ner they chose. Again, there was

discussion throughout, focusing on

the theme, the reason for the theme

and pictures chosen, their signifi-

cance to the client and any difficul-

ties in task performance.

At the end of this process, the

occupational therapist generated an

occupational therapy (OT) problem

list and placed it on the client's chart.

The RO did not have access to the

charts at this point in the study.

Nursing Evaluation:

This evaluation was carried out

within 48 hours of the admission of

the client to the unit. The evaluation

was always carried out on a one-to-

one basis by the nurse assigned to

the client. She/he did a nursing his-

tory and then generated the nursing

problem list which was placed on the

client's chart at that time.

October/Octobre 1986

201

CJOT Vol. 53 No. 4

Creation of the functional terms

Dictionary:

Given the difference in terminol-

ogy employed by the three profes-

sions involved in creating the 3

problem lists, (i.e., psychology in the

H-T-P, occupational therapy in the

O.T. assessment and nursing in the

nursing evaluation), it was necessary

to create a `dictionary' of terms. Par-

ticularly, it was the purpose of this

dictionary to provide a reference for

the translation of H-T-P terms into

OT terms. Initially, a one for one

translation was planned, however,

this proved to be impossible. Conse-

quently, it was necessary to establish

a list of major categories using

occupational therapy functional

words. Descriptors found on the

H-T-P were then grouped under

these categories (see Table 3 for ex-

amples).

The dictionary was given to 'ex-

perts' (psychiatric occupational ther-

apy faculty otherwise not associated

with this study) to: (1) evaluate the

face validity of the placement of

H-T-P descriptors under the various

categories and (2) expand the num-

ber of categories. The experts were

in agreement with the H-T-P terms

appearing under the various cate-

gories of the dictionary, only recate-

gorizing three terms.

The experts also did not create

new categories although they did

suggest the subdivision of the Activi-

ties of Daily Living category into two

subheadings (Dependence and

Independence). However, given the

nature of the occupational therapy

and the nursing data base, these

were inappropriate subheadings

and, therefore, were not used. This

was the dictionary used in all further

evaluation of the H-T-P problem

lists generated.

It should be noted that the use of

the dictionary resulted in a major

reduction of the data which must be

kept in mind in the interpretation

of the results of this study. This,

however, was unavoidable.

Comparison of Problem Lists:

Once all three evaluations were

completed with a client, the RO

transferred the three problem lists

from their respective sources onto a

summary sheet. The RO then com-

pared the problem lists and indicat-

ed on the summary sheet if there was

agreement between either the H-T-P

problem list and the OT problem list

or the H-T-P problem list ` and the

Nursing problem list. Often a judg-

ment was necessary to deem two

problems as the same.

To validate the judgments of the

RO and to remove any possible re-

searcher bias, the following steps

were taken by the two investigators:

(1) independent of the RO, all prob-

lems were extracted from the sum-

mary sheets to create separate, de-

tached lists of H-T-P problems,

nursing problems and OT problems.

(2) Each of these lists was then taken

on its own and the problems that

appeared to be essentially the same

were grouped under one subsumer,

e.g., the problems, major depression,

reactive depression, depressive neu-

rosis and recurrent depression were

all grouped under the subsumer de-

pression. (3) These subsumers were

then placed under the H-T-P dic-

tionary categories resulting in the

corresponding terms list (see

Table 4). From Table 4, it can be

seen that a number of subsumers

could not be placed under any of

the H-T-P dictionary categories. It

was, therefore, necessary to generate

a ninth category called `OTHER'

which was added to both the dic-

tionary and the corresponding terms

list. (4) The corresponding terms list

was then checked against the H-T-P

dictionary. Where there was a dis-

crepancy, the categorization of the

dictionary obtained. (5) For each

client, the corresponding list was

then used to check for matches be-

tween H-T-P problems and Nursing

problems and between H-T-P prob-

lems and OT problems, as appearing

on his/her individual summary

sheet. (6) The investigator's problem

match for each client was then veri-

fied against the RO's matched list

and percentage agreement between

RO and senior investigators was cal-

culated.

202

October/Octobre 1986

CJOT Vol. 53 No. 4

October/Octobre 1986

203

x 100

CJOT Vol. 53 No. 4

The mean percentage agreement

between the senior investigators and

the RO was 85.77% with a standard

deviation of 12.80. The mode was

100% which occurred for 10 clients

(25% of the population). This indi-

cates fairly good agreement and,

therefore, confidence in the data ob-

tained. Where there was a

disagreement between the RO and

the investigators, it was the decision

of the investigators as indicated on

Table 4 that obtained. This was

done because Table 4 was generated

`blind', whereas the RO's judgment

was not made blind.

These data were used to calculate

the parameters of validity: percent-

age agreement and percentage ac-

counted for.

Percentage agreement, calculated

by the formula:

total number of

matches

x100

total number of

H-T-P problems

is simply the percentage of the prob-

lems identified by H-T-P that were

also identified by either OT or nurs-

ing. Problems unique to the H-T-P

lists would automatically reduce the

percentage agreement between the

lists. Since it is not known (nor was

it the purpose of this study to deter-

mine) whether the unique problems

are valid problems, this is an impor-

tant calculation, a method of calcu-

lating which does not penalize the

H-T-P for unique problems is also

important.

Percentage accounted for, calcu-

lated by the formula:

total number of

matches with

Nursing (or OT)

total number of

nursing (or OT)

problems

is the percentage of the problems

identified by nursing or OT that were

also identified by the H-T-P. This

calculation is not influenced by

unique H-T-P problems.

Comparison of time:

The average time required to per-

form each of the evaluations was

estimated as accurately as possible

by the people involved with the ad-

ministration of the assessments and

compared at face value.

Materials:

The H-T-P drawing form and

post-drawing interrogation

folder and scoring folder

A Catalog for the Qualitative

Interpretation of the House-

Tree-Person (H-T-P) (Jolles,

1981)

Functional Terms Dictionary

OPencils and erasers

Tile trivet 6" x 6" trivet, 121

5/16" square tiles of various

colors

OGlue

OGrout

OA sheet of paper 18" X 24"

OMagazines

OScissors

Results

The number of problems identi-

fied by each of the three methods

of assessment per client appear in

Table 5. As can be seen, the H-T-P

identified the largest number of

problems but in all cases the actual

number of problems was small.

The observation that H-T-P tend-

ed to identify more problems indi-

cated that there were problems

unique to the H-T-P, i.e., problems

not identified by either nursing or

OT. At the same time, there were

missing problems, i.e., problems

identified by nursing or OT that were

not identified by the H-T-P. The

H-T-P identified an average of two

unique problems per client over the

team effort and missed an average

of 1.03 of the client problems as

identified by nursing and an average

of .95 of the client problems as iden-

tified by OT (see Table 5).

agreement

% accounted for

204

October/Octobre 1986

pr^, ar^s ces .-Deeeeee

0e: -

e

vs_

3

L

CJOT Vol. 53 No. 4

The percentage agreement and

percentage accounted for appear in

Table 6. As can be seen, in all cases,

the percentage accounted for is the

greater. Also, both percentage

agreement and the percentage ac-

counted for between OT and the

H-T-P were higher than for nursing.

The nature of the problems iden-

tified by the H-T-P spanned all the

functional categories set out at the

creation of the dictionary as did the

nature of the problems unique to the

H-T-P and the nature of missing

problems. In the majority of cases

the missing problems appeared in-

frequently (see Table 7).

Of interest in Table 7 are the

category specific discrepancies be-

tween H-T-P and Nursing and OT

problems. Namely, sexual problems

were identified 30 times by the

H-T-P and 28 of these were unique

to the H-T-P. Likewise, 14 of the 39

self-concept problems were identi-

fied by the H-T-P alone. Alternati-

vely, mood/affect problems were

missed 12 times compared to nurs-

ing. These misses were comprised of

4 different problems. Work problems

were identified 17 times in the H-T-P

but were missed 21 times when com-

pared to the OT lists. There were 6

different problems which were

missed repeatedly.

The H-T-P proved to be a consid-

erably more efficient tool compared

to the OT assessment. The average

time taken to administer the H-T-P,

including the post-drawing interro-

gation was 40 minutes. The interpre-

tation of the projective material and

the answers to the questions took

approximately another 50 minutes

per client, for a total of 90 minutes

for the complete administration of

the H-T-P. The OT assessment took

approximately 5 hours (300 minutes)

to complete per client.

Discussion

The H-T-P is clearly a more effi-

cient method of evaluation than the

OT assessment, taking 3+ hours less

to complete. Of particular impor-

tance here is the finding that this

gain in time is not accompanied by

a great loss of information. The

H-T-P identified 75.19% of the prob-

lems identified by the OT assess-

ment. Given that OT typically only

identified four problems, this means

that only one problem was missed.

If this is counter-balanced with the

observation that the H-T-P typically

identified two additional problems

over the OT list, it suggests that the

H-T-P is as proficient at identifying

problems as is the OT assessment.

In terms of the unique problems,

it must be remembered that there

was no method available to assess

the validity of these problems. How-

ever, the observation that many of

the unique problems were sexual

problems and, indeed, only 2 of the

30 sexual problems identified by the

H-T-P were identified elsewhere

suggests that the unique problems

may be indicative of areas where the

H-T-P is more proficient.

October/Octobre 1986

205

CJOT - Vol. 53 - No. 4

In terms of the missing problems,

a similar phenomenon is suggested.

The H-T-P only identified work

problems in 17 instances but missed

21 occurrences of the work problems

identified by OT. This again could

be interpreted as a statement on the

relative areas of proficiency of the

two instruments.

Thus, it would appear that the

H-T-P is an efficient and useful tool

relative to the OT assessment, par-

ticularly if it is augmented by a work

assessment.

In comparison to the nursing eval-

uation, again the H-T-P seems to

account for a substantial proportion

of the problems identified (66.42%)

typically missing no problems. (It

should be noted that the low per-

centage agreement relative to a

mode of zero for missing problems

is more reflective of the small num-

bers being dealt with here than of

poor agreement). The area most fre-

quently having missing problems

was mood/affect. This occurred in

12 instances although there were

only 4 different problems. Since the

H-T-P did identify 34 mood/affect

problems, 8 of which were unique,

it suggests that the H-T-P is not

deficient in this area but that specific

problems should be looked at - such

an analysis was beyond the scope of

this paper.

In interpreting the results of this

research and in considering the im-

plications of these for the identifica-

tion of specific problems, the proce-

dures used here must be

remembered. It must be recognized

that in the process of creating the

dictionary, specific problems were

incorporated into major categories

and thus a lot of specific data were

lost. While this was a necessary pro-

cedure to allow for comparisons be-

tween lists, it resulted in reduction

of data and loss of specificity. Thus,

the results presented here can only

be considered in general terms.

Conclusion

Percentage of agreement between

Nursing and H-T-P and between OT

and H-T-P are low. This is assumed

to be, in part, a consequence of the

number of unique problems identi-

fled by the H-T-P. The percentage

accounted for was considerably

higher. Since this parameter is not

affected by unique problems, it is

considered to be more meaningful.

It is important to remember that the

latter is true only if the unique prob-

lems identified by the H-T-P are true

problems. If not, then percentage

agreement is a more accurate reflec-

tion of the performance of the HT-

P. This study was not intended to

verify whether unique problems

were true or false. However, since

the unique problems were largely in

one area, it seemed to reflect the

differences in the orientation of the

instruments (e.g., sexual problems).

Thus, the percentage accounted for

may indeed be the more significant

parameter.

In summary: The problems iden-

tified by the H-T-P were the same

as those identified by nursing and

OT in 66.4% and 75.2% of the cases

respectively. In some instances, the

H-T-P missed problems while in

others it identified unique problems

not noted by nursing or OT. There-

fore, for a thorough assessment, all

three procedures should be used.

However, given the high percentage

of OT problems accounted for by the

H-T-P, if a quick assessment is re-

quired, the H-T-P alone would be

appropriate - taking special care to

look for work-related problems.

REFERENCES

Bieliauskas, V.J. (1980). The House Tree Per-

son (H-T-P) research review: 1980 edition,

Los Angeles, Western Psychological Serv-

ices.

Blain, G.H., Bergner, R.M., Lewis, M.L. &

Goldstein, M.A. (1981). The use of objecti-

vely scorable House-Tree-Person indica-

tors to establish child abuse. Journal of

Clinical Psychology, 37, 673.

Buck, J.N. (1981). The House-Tree-Person

Technique - revised manual: Los Angeles,

Western Psychological Services.

Cooper, L. & Caston, J. (1969). Size of figures

drawn before and after stress. Perceptual

& Motor Skills, 29, 57-58.

Davis, C.J. & Hoopes, J.L. (1976). Compari-

son of House-Tree-Person drawings of

young deaf and hearing children. School

Psychology Digest, 5, 29-35.

Devore, J.E. & Fryrear, J.L. (1976). Analysis

of juvenile delinquents' hole drawing

responses on the tree figure of the House-

Tree-Person Technique. Journal of Clinical

Psychology, 32, 731-736.

Doorbar, R.M. (1967). Psychological testing

of transsexuals: a brief report of results

from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence

Scale, The Thematic Apperception Test,

and the House-Tree-Person Test. Transac-

tions of the New York Academy of Sciences,

29, 455-462.

Ernst, P., Beran, B., Badash, D., Kosovsky,

R. & Kleinhauz, M. (1977). Treatment of

the aged mentally ill: further unmasking

of the effects of a diagnosis of chronic brain

syndrome. Journal of the American Geria-

trics Society, 25, 466-469.

Gasparini, B., Shealy, C. & Walters, D. (1980).

Differences in size and spatial placement

of drawings of left versus right hemisphere

brain-damaged patients. Journal of Con-

sulting Clinical Psychology, 48, 670-672.

Gording, E.J. & Match, E. (1968). Personality

changes of certain contact lens patients.

Journal of the American Optometric Associ-

ation, 39, 266-269.

Hammer, E.F. (1978). The Clinical Applica-

tion for Projective Drawings. Charles C.

Thomas. Springfield.

Hammer, E.F. (1981). The House-Tree-Person

(H-T-P) clinical research manual. Los An-

geles. Western Psychological Se rvices.

Haworth, M.R. (1965). H-T-P: House-Tree-

Person Projective Technique. In O.K.

Buros (Ed). The Sixth Mental Measure-

ments Yearbook. Highland Park, N.J.:

Gryphon Press, 6:214, 434-436.

Hoover, T.O. (1978). Skydivers: Speculations

of Psychodynamics. Perceptual & Motor

Skills, 47, 629-630.

Jokes, 1. (1981). A catalog for the qualitative

interpretation of the House-Tree-Person

(H-T-P). Los Angeles. Western Psycholo-

gical Services.

Kline, P. & Svaste, X.B. (1981). The House,

Tree, Person Test (HTP) in Thailand with

4 and 5 year old children: A comparison

of Thai and British results. British Journal

of Projective Psychology and Personality

Study, 26, 1-11.

Kuhlman, T.L. & Bieliauskas, V.J. (1976). A

comparison of black and white adolescents

on the HTP. Journal of Clinical Psychology,

32, 728-731.

Mosey, A.C. (1968). Occupational Therapy:

Theory and Practice. Unpublished manu-

script.

Occupational Therapy Department (undat-

ed). Occupational Therapy Se rvices Initial

Interview. University Hospital, London,

Ontario, Canada.

Perkins, C.F. & Wagemaker, H. (1977). Art

therapy with a dialyzed schizophrenic. Art

Psychotherapy, 4, 137-147.

Peyru, G. and De Pastrana-Borrero, A.G.

(1977). The position of conflict in Psycho-

therapy Acta Psiguiatrico Y Psicologia de

America Latina, 23, 58-66.

Platzer, W.S. (1976). Effect of perceptual

motor training on gross motor skill and

self-concept of young children. American

Journal of Occupational Therapy, 30, 422-

428.

206

October/Octobre 1986

CJOT Vol. 53 No. 4

Robin, A.l. and Haworth. M.R. (Eds.) (1971).

Projective Techniques with Children. Grune

and Stratton. New York.

Rosenfeld, M.S. (1982). A model for activity

inte rvention in disasterstricken communi-

ties. American Journal of Occupational

Therapy, 36. 229-235.

Seligman. L. (1979). Understanding the black

foster child through assessment. Journal of

Non-White Concerns in Personnel and

Guidance, 7, 183-191.

Tropauer. A., Franz, M.N. & Dilgard. V.W.

(1970). Psychological aspects of the care of

children with cystic fibrosis. American

Journal of Diseases of Children. /19. 424-

432.

Ullman. K.C.. Moore. R.W. & Reidy. M.

(1977). Atopic Eczema: A clinical psychia-

tric study. Journal of Asthma Research, 14.

91-99.

Wenck. L.S. (1981). House-Tree-Person draw-

ings: an illustrated diagnostic handbook.

Los Angeles. Weste rn Psychological Serv-

ices.

Wildman. R.W., Wildman. R.W. & Smith.

R.D. (1967). Expansiveness-Constriction

on the H-T-P as indicators of extroversion-

introversion. Journal of Clinical Psvcholo

gv. 23. 493-494.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge with appre-

ciation the ongoing assistance, direction and

encouragement of Arlene Shimeld. Manager.

Occupational Therapy Se rvices. Unive rs ity

Hospital.

Rsum

Cette tude a tmene dans le but de dterminer si le test de dessin

valeur projective H.T.P. (House, Tree, Person) de Buck s'est avr

une mthode permettant d'identifier d'une manire valable et efficace

une liste de problmes pour le traitement d'ergothrapie. cette fin,

on a menune tude comparative double insu. Un chercheur entran

a administr le test de personnalit H.T.P. quarante clients dont il

ne savait rien, ces clients prsentaient des problmes psychiatriques aigus.

Ils ont galement t valus sur le plan de l'ergothrapie par leur

ergothrapeute et sur le plan des soins infirmiers par l'infirmire qui

leur tait assigne. Dans chacun des cas, une liste de problmes a t

dresse, ces listes ont alors tcompares afin de dfinir le pourcentage

de concordance entre les problmes. ainsi que le pourcentage de problmes

dj connus et le temps ncessaire pour fournir les diffrentes listes.

Le pourcentage de concordance entre les listes de proh!cnes obtenues

grce au test H.T.P. et par l'valuation sur le plan des sinus infirmiers.

et le pourcentage de concordance entre les listes obtenues par le test

H.T.P. et par l'valuation ergothrapeutique ont t respectivement de

32.88 et de 47.18. Les pourcentages des problmes connus ont t de

66.42 et de 75.19 respectivement. Les diffrences sont examines. Le

temps ncessaire pour administrer le test H.T.P. s'est avr considrable-

ment infrieur l'valuation ergothrapeutique traditionnelle. Pour

conclure, le test H.T.P. s'est avr un outil de dpista apprciable.

October/Octobre 1986

207

You might also like

- A Beginner's Guide to Personal Construct Therapy with Children and Young PeopleFrom EverandA Beginner's Guide to Personal Construct Therapy with Children and Young PeopleNo ratings yet

- House Tree Person DrawingsDocument4 pagesHouse Tree Person DrawingsIvanNo ratings yet

- Practitioner's Guide to Assessing Intelligence and AchievementFrom EverandPractitioner's Guide to Assessing Intelligence and AchievementNo ratings yet

- House Tree PersonDocument6 pagesHouse Tree PersonJack FreedmanNo ratings yet

- BenderDocument1 pageBenderestellamarieNo ratings yet

- House Tree Person Test ReportDocument17 pagesHouse Tree Person Test ReportKaren Gail Comia100% (2)

- Kinetic Family DrawingDocument1 pageKinetic Family Drawingakraam ullah50% (2)

- House Tree PersonDocument34 pagesHouse Tree PersonJackylou Blanco100% (1)

- Rotter Incompelete Sentence Blank RisbDocument27 pagesRotter Incompelete Sentence Blank Risbbobbysingersyahoo100% (1)

- House Tree PersonDocument25 pagesHouse Tree PersonnatsmagbalonNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument5 pagesReportiqra uroojNo ratings yet

- Psychological Report WritingDocument28 pagesPsychological Report Writinggwuan31No ratings yet

- A Comparison of The Emotional Indicators On The House-Tree-Person PDFDocument214 pagesA Comparison of The Emotional Indicators On The House-Tree-Person PDFKrisdaryadiHadisubroto100% (1)

- Bender Gestalt scoring systems focus on visual-motor difficultiesDocument2 pagesBender Gestalt scoring systems focus on visual-motor difficultiesShalini DassNo ratings yet

- The House-Tree-Person (HTP) Projective Personality Test ExplainedDocument10 pagesThe House-Tree-Person (HTP) Projective Personality Test ExplainedRidaNo ratings yet

- Examples of Scoring in The RorschachDocument1 pageExamples of Scoring in The Rorschachkynedyha3826100% (2)

- Projective Techniques IntroductionDocument16 pagesProjective Techniques IntroductionIsabel SamonteNo ratings yet

- TatDocument4 pagesTatlove148No ratings yet

- The Thematic Apperception TestDocument4 pagesThe Thematic Apperception TestDeepika Verma100% (1)

- The Kinetic Family Drawing Test in Art TherapyDocument5 pagesThe Kinetic Family Drawing Test in Art TherapyArielle RamirezNo ratings yet

- HTPDocument27 pagesHTPKate BumatayNo ratings yet

- Psych ReportDocument4 pagesPsych ReportArscent Piliin100% (1)

- Bender Gestalt TestDocument2 pagesBender Gestalt TestIqbal Baryar100% (1)

- Psychological Test ReportDocument3 pagesPsychological Test Reportaids100% (1)

- A Study On The Kinetic Family Drawings by Children With Different Family StructuresDocument33 pagesA Study On The Kinetic Family Drawings by Children With Different Family StructuresInterfaith MarriageLB100% (1)

- RorschachDocument33 pagesRorschachNoDurianNo ratings yet

- House-Tree-Person test reveals personality traitsDocument1 pageHouse-Tree-Person test reveals personality traitsTrisha Mae Milca100% (1)

- Thematic Appreciation TestDocument66 pagesThematic Appreciation Testankydeswal50% (2)

- Drawing Interpretations for Assessing Student MaturityDocument5 pagesDrawing Interpretations for Assessing Student Maturitynicklan100% (2)

- Hermann RorschachDocument39 pagesHermann RorschachM.Phil. Clinical Psychology Batch 1920No ratings yet

- KFD by Robert Burns and KaufmanDocument124 pagesKFD by Robert Burns and KaufmanDi Hidalgo Cabanlit100% (8)

- Projective Personality TestsDocument43 pagesProjective Personality TestsTejus Murthy A G100% (1)

- Demographic and psychological assessment reportDocument3 pagesDemographic and psychological assessment reportmobeenNo ratings yet

- House Tree Person InterpretationsDocument2 pagesHouse Tree Person InterpretationsMrsJamesMcAvoy100% (1)

- Draw Me A Person Psychological TestDocument13 pagesDraw Me A Person Psychological Testfreedriver_13No ratings yet

- Thematic Apperception Test 8Document8 pagesThematic Apperception Test 8api-610105652No ratings yet

- Summary of Emotional Indicators (E. M. Koppitz)Document2 pagesSummary of Emotional Indicators (E. M. Koppitz)Nazema_SagiNo ratings yet

- House Tree Person TestDocument2 pagesHouse Tree Person TestDivina Gracia PettyferNo ratings yet

- MBTI - Validity and ReliabilityDocument28 pagesMBTI - Validity and Reliabilitypalak duttNo ratings yet

- 16 Personality Factors: By: AwakenDocument30 pages16 Personality Factors: By: AwakenArzoo Sinha100% (1)

- Malingering On The Personality Assessment Inventory: Identification of Specific Feigned DisordersDocument7 pagesMalingering On The Personality Assessment Inventory: Identification of Specific Feigned DisordersMissDSKNo ratings yet

- KFD Scoring MethodDocument12 pagesKFD Scoring MethodDorka9100% (3)

- Projective Tests PsychologyDocument4 pagesProjective Tests PsychologytinkiNo ratings yet

- Case Presentation 3Document4 pagesCase Presentation 3api-285918237No ratings yet

- Detailed ManualDocument37 pagesDetailed ManualRaymond I.100% (2)

- Understand WAIS-IV Indexes & Subtests for IQ TestingDocument4 pagesUnderstand WAIS-IV Indexes & Subtests for IQ TestingkamyuzNo ratings yet

- TESTING REPORT FinalDocument84 pagesTESTING REPORT FinalFaizan AhmedNo ratings yet

- Detailed Procedure of Thematic Apperception Test: PersonalityDocument15 pagesDetailed Procedure of Thematic Apperception Test: PersonalityTalala Usman100% (1)

- Buck 1948Document9 pagesBuck 1948Carlos Mora100% (1)

- Thematic Apperception Test, (T.A.T) : Presses and EnvironmentDocument17 pagesThematic Apperception Test, (T.A.T) : Presses and EnvironmentElishbah Popatia100% (1)

- Rorschach AdminDocument3 pagesRorschach Adminloanthi666No ratings yet

- Clinical AssessmentDocument26 pagesClinical Assessment19899201989100% (2)

- DAP Scoring Guide PDFDocument4 pagesDAP Scoring Guide PDFLeo Gondayao0% (1)

- Hose Tree Person (HTP)Document43 pagesHose Tree Person (HTP)mhrizvi_1279% (33)

- Cat TatDocument279 pagesCat TatAndreea DobreanNo ratings yet

- Factor in R PDFDocument4 pagesFactor in R PDFrspecuNo ratings yet

- Big Five Jap - OutDocument428 pagesBig Five Jap - OutrspecuNo ratings yet

- Measuremente of Burnout A ReviewDocument17 pagesMeasuremente of Burnout A ReviewrspecuNo ratings yet

- Augustus de Morgan-Elementary Illustrations of The Differential and Integral Calculus-Chicago, The Open Court Pub. Co. - London, K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co (1909)Document152 pagesAugustus de Morgan-Elementary Illustrations of The Differential and Integral Calculus-Chicago, The Open Court Pub. Co. - London, K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co (1909)rspecuNo ratings yet

- Kolmogorov A.n.-Foundations of The Theory of Probability-Chelsea (1956)Document92 pagesKolmogorov A.n.-Foundations of The Theory of Probability-Chelsea (1956)rspecuNo ratings yet

- Bach - Prelude and Fugue NoDocument5 pagesBach - Prelude and Fugue NorspecuNo ratings yet

- Donald W. Kahn-Topology - An Introduction To The Point-Set and Algebraic Areas-Dover Publications (1995)Document226 pagesDonald W. Kahn-Topology - An Introduction To The Point-Set and Algebraic Areas-Dover Publications (1995)rspecuNo ratings yet

- Spearman 1904aDocument31 pagesSpearman 1904amuellersenior3016No ratings yet

- Geometry of Rene DescartesDocument256 pagesGeometry of Rene DescartesrspecuNo ratings yet

- Drama Games For Acting ClassesDocument12 pagesDrama Games For Acting ClassesAnirban Banik75% (4)

- ESL Academic Writing ExtractsDocument7 pagesESL Academic Writing Extractsmai anhNo ratings yet

- Ph.D. Enrolment Register As On 22.11.2016Document35 pagesPh.D. Enrolment Register As On 22.11.2016ragvshahNo ratings yet

- 17th Anniversary NewsletterDocument16 pages17th Anniversary NewsletterDisha Counseling CenterNo ratings yet

- Lesson-Plan-Voc Adjs Appearance Adjs PersonalityDocument2 pagesLesson-Plan-Voc Adjs Appearance Adjs PersonalityHamza MolyNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Purposive CommunicationDocument13 pagesModule 1 Purposive CommunicationJoksian TrapelaNo ratings yet

- The What Why and How of Culturally Responsive Teaching International Mandates Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument18 pagesThe What Why and How of Culturally Responsive Teaching International Mandates Challenges and Opportunitiesapi-696560926No ratings yet

- Derewianka B. 2015 A new Grammar Companion for Teachers Chapter 2Document92 pagesDerewianka B. 2015 A new Grammar Companion for Teachers Chapter 2Xime NicoliniNo ratings yet

- Demonstration - ANANDDocument22 pagesDemonstration - ANANDAnand gowda100% (1)

- Math 1 Table of ContentsDocument4 pagesMath 1 Table of ContentshasnifaNo ratings yet

- Present Yourself SB L2-1Document14 pagesPresent Yourself SB L2-1Hanan HabashiNo ratings yet

- Srila Prabhupada On 64 Rounds - 0Document4 pagesSrila Prabhupada On 64 Rounds - 0Anton ArsenNo ratings yet

- Promising Questions and Corresponding Answers For AdiDocument23 pagesPromising Questions and Corresponding Answers For AdiBayari E Eric100% (2)

- Intro To Emails, Letters, Memos Teacher's Notes + Answers (Languagedownload - Ir) PDFDocument1 pageIntro To Emails, Letters, Memos Teacher's Notes + Answers (Languagedownload - Ir) PDFjcarloscar1981No ratings yet

- 1a.watch, Listen and Fill The GapsDocument4 pages1a.watch, Listen and Fill The GapsveereshkumarNo ratings yet

- Individual Student Profile-3Document8 pagesIndividual Student Profile-3api-545465729No ratings yet

- BALMES Module1 Assingment Autobiography GECUTS 18Document3 pagesBALMES Module1 Assingment Autobiography GECUTS 18Loki DarwinNo ratings yet

- McManus Warnell CHPT 1Document46 pagesMcManus Warnell CHPT 1CharleneKronstedtNo ratings yet

- Community Outreach PaperDocument7 pagesCommunity Outreach Paperapi-348346538No ratings yet

- Impact of Sports on Student Mental HealthDocument36 pagesImpact of Sports on Student Mental HealthPriyanshu KumarNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan EnglishDocument3 pagesLesson Plan EnglishagataNo ratings yet

- Commercial Arithmetics PDFDocument2 pagesCommercial Arithmetics PDFDawn50% (2)

- 2010 11catalogDocument313 pages2010 11catalogJustin PennNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Education Basic Features: EssentialismDocument2 pagesPhilosophy of Education Basic Features: EssentialismFerliza Cudiamat PacionNo ratings yet

- 0,,BBA 305, Business Values and EthicsDocument2 pages0,,BBA 305, Business Values and EthicsKelvin mwaiNo ratings yet

- Grade 6 Food Preservation Weekly LessonDocument67 pagesGrade 6 Food Preservation Weekly Lessonchona redillasNo ratings yet

- Informal Letter Choosing Laptop vs DesktopDocument28 pagesInformal Letter Choosing Laptop vs DesktopPuteri IkaNo ratings yet

- Ateneo Zamboanga Nursing FormsDocument17 pagesAteneo Zamboanga Nursing FormsRyan MirandaNo ratings yet

- MGT-303 EntrepreneurshipDocument10 pagesMGT-303 EntrepreneurshipAli Akbar MalikNo ratings yet

- English Teaching ProfessionalDocument64 pagesEnglish Teaching ProfessionalDanielle Soares100% (2)