Professional Documents

Culture Documents

S 0002934307003610

Uploaded by

Natalia Rafael0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views4 pagesRheumatoid arthritis is a chronic, systemic, inflammatory autoimmune disorder. It afflicts an estimated 25 men and 54 woman per 100,000 population. Early use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologics has improved outcomes.

Original Description:

Original Title

s 0002934307003610

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentRheumatoid arthritis is a chronic, systemic, inflammatory autoimmune disorder. It afflicts an estimated 25 men and 54 woman per 100,000 population. Early use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologics has improved outcomes.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views4 pagesS 0002934307003610

Uploaded by

Natalia RafaelRheumatoid arthritis is a chronic, systemic, inflammatory autoimmune disorder. It afflicts an estimated 25 men and 54 woman per 100,000 population. Early use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologics has improved outcomes.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

OFFICE MANAGEMENT

Rheumatoid Arthritis: Diagnosis and Management

Vikas Majithia, MD,

a,b

Stephen A. Geraci, MD

a,b

a

Department of Medicine, University of Mississippi School of Medicine, Jackson,

b

Medical Service, G.V. (Sonny) Montgomery Veterans

Affairs Medical Center, Jackson, Miss.

ABSTRACT

Accurate diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis may be difcult early in its course and demands high clinical

suspicion, astute examination, and appropriate investigations. Early use of disease-modifying antirheu-

matic drugs and biologics has improved outcomes but requires close monitoring of disease course and

adverse events. 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

KEYWORDS: Diagnosis; Review; Rheumatoid arthritis; Therapy

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic, systemic, inammatory

autoimmune disorder causing symmetrical polyarthritis of

large and small joints, typically presenting between the ages

of 30 and 50 years.

1

The most common inammatory ar-

thritis, it aficts an estimated 25 men and 54 woman per

100,000 population and is responsible for 250,000 hospital-

izations and 9 million physician visits in the US each

year.

1-3

The etiology of rheumatoid arthritis is not fully under-

stood but involves a complex interplay of environmental

and genetic factors. Genetics also play a role in disease

severity. A triggering event, possibly autoimmune or infec-

tious, initiates joint inammation.

2

Complex interactions

among multiple immune cell types and their cytokines,

proteinases, and growth factors mediate joint destruction

and systemic complications.

2

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis is primarily clinical.

The typical presentation is polyarticular, with pain, stiff-

ness, and swelling of multiple joints in a bilateral, symmet-

ric pattern. A minority of patients present with oligoarticular

asymmetric involvement.

1

The onset is usually insidious,

with joint symptoms emerging over weeks-months and of-

ten accompanied by anorexia, weakness, or fatigue. Patients

usually note morning stiffness lasting more than an hour.

Commonly involved joints are the wrists, proximal inter-

phalangeal, metacarpophalangeal, and metatarsophalangeal

joints, with distal interphalangeal joints and spinal joints

usually spared.

1

Typical examination ndings include

swelling, bogginess, tenderness and warmth of, with at-

rophy of muscles near, the involved joints. Weakness is

out of proportion to tenderness.

Rarely, patients may present with single joint involve-

ment or with severe systemic symptoms of fever, weight

loss, lymphadenopathy, and multiple organ involvement

such as lung or heart.

1

Infection-related reactive arthropathies, seronegative

spondyloarthropathies, and other connective tissue diseases

may have symptoms in common with rheumatoid arthritis,

as may an array of endocrine and other disorders. These

must be excluded in the initial diagnostic evaluation.

1

Table 1

lists some common diseases that should be considered in the

differential diagnosis.

There is no single test that conrms rheumatoid arthritis.

Initial laboratory tests should include a complete blood cell

count with differential, rheumatoid factor, and erythrocyte

sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein. Rarely, joint aspi-

ration also may be required, especially with monoarticular

presentations, to rule out infectious or crystal-induced ar-

thritis. Baseline renal and hepatic function tests are recom-

mended to guide medication choices.

3

Anticyclic citrulli-

nated peptide antibody carries high specicity and positive

predictive value but is present in fewer than 60% of rheu-

Requests for reprints should be addressed to Vikas Majithia, MD,

Division of Rheumatology and Molecular Immunology, Department of

Medicine, University of Mississippi School of Medicine, 2500 N. State

Street, Jackson, MS 39216.

E-mail address: vikasmajithia@medicine.umsmed.edu

0002-9343/$ -see front matter 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.04.005

The American Journal of Medicine (2007) 120, 936-939

matoid arthritis patients.

4

Tests to rule out other disorders in

the differential diagnosis (Table 1) should be performed as

clinically indicated.

The American College of Rheumatology criteria (Table 2)

are helpful in formally diagnosing and following rheu-

matoid arthritis patients in research trials.

5

In the clinical

setting, a denitive diagnosis using these criteria is not

possible in all the cases; they should be used only in com-

bination with all other available information in an individual

case.

KEY POINTS: DIAGNOSIS AND INITIAL

MANAGEMENT DECISIONS

There are 2 questions for the primary care physician when

evaluating a patient with arthritis: Is the diagnosis of rheu-

matoid arthritis likely? Does the patient need early treat-

ment or referral to a rheumatologist, or both? Findings

making rheumatoid arthritis the likely diagnosis and prompting

initiation of treatment are:

Joint swelling (and pain) of 3 or more joints

Metacarpal or metatarsal joint involvement (a positive

squeeze test, ie, signicant pain when squeezed across

these joints)

Morning stiffness lasting more than 30 minutes

Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive pro-

tein, and rheumatoid factor

Referral to a rheumatologist is indicated if the diagnosis

is unclear, more than 5 joints or large joints are involved

with accompanying signicant subjective symptoms, or lab-

oratory abnormalities are present.

TREATMENT

A comprehensive approach to managing rheumatoid arthri-

tis consists of patient education, physical/occupational ther-

apy, and drug treatment. Patients should be educated about

the disease and referred to these ancillary specialists to

maintain joint function and delay disability. Drug treatment

generally involves a 3-pronged approach: nonsteroidal anti-

inammatory drugs and low-dose oral or intra-articular glu-

cocorticoids; disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; and

consideration of biologic response modiers/biologics.

Nonsteroidal anti-inammatory drugs reduce joint pain and

swelling, but do not alter the disease course and should not

be used alone.

3

Steroids (prednisone 10 mg daily or equiv-

alent) relieve symptoms and may slow joint damage;

3

they

should be prescribed at a low dose for short duration, pri-

marily as bridge therapy, and with daily calcium (1500

mg) and vitamin D (400-800 IU) oral supplements to limit

bone demineralization.

3

All patients with rheumatoid arthritis should be evalu-

ated for disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs treatment.

3

Early use slows disease progression and improves overall

long-term prognosis.

3

Although there is consensus among

rheumatologists that rheumatoid arthritis should be treated

early and aggressively, a number of issues (choice of initial

therapy, timing and patient criteria for initiation of combi-

nation therapy, or use of biologics) remain under evaluation.

The following is an approach consistent with the avail-

able evidence. Patients with mild disease (typically 5

joints involved and mild subjective symptoms) and normal

radiographic ndings can receive hydroxychloroquine,

sulfasalazine, minocycline, or possibly methotrexate.

Methotrexate remains the initial treatment of choice in

moderate-severe disease (typically 5 joints or large joint

involvement with signicant subjective symptoms) or ra-

diographic changes of bone loss/erosion. The target dose

(15 mg/week) should be reached within 6-8 weeks if toler-

ated. When response is inadequate, leunomide, azathio-

prine, or combination therapy (methotrexate plus another

agent) may be considered. Combinations of disease-modi-

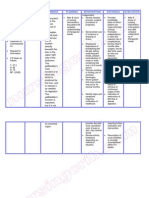

Table 2 Classication Criteria for Rheumatoid Arthritis*

Morning stiffness (lasting 1 hour)

Arthritis of 3 or more joint areas (areas are right or left

proximal interphalangeal, metacarpophalangeal, wrist,

elbow, knee, ankle, and metatarsophalangeal joints)

Arthritis of hand joints (proximal interphalangeal or

metacarpophalangeal joints)

Symmetric arthritis, by area

Subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules

Positive rheumatoid factor

Radiographic changes (hand and wrist, showing erosion of

joints or unequivocal demineralization around joints)

*At least 4 are needed for diagnosis. Adapted from Arnett et al:

5

Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315-324. Copyright John Wiley & Sons, Inc.,

1988, reprinted with permission of Wiley-Liss, Inc., a subsidiary of

John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Present for 6 weeks.

Table 1 Diseases that Can Mimic Rheumatoid Arthritis

Category Common Examples

Other connective

tissue syndromes

Systemic lupus erythematosus,

Systemic vasculitides,

Scleroderma

Systemic diseases Sarcoidosis, Stills disease, Infective

endocarditis, Rheumatic fever

Spondyloarthropathies Psoriatic arthritis, Reactive arthritis

Infectious arthritis Viral arthritides (esp. Parvo virus),

Bacterial arthritis, Gonococcal

arthritis

Crystal-induced

arthritis

Polyarticular gout

Endocrinopathies Thyroid disorders

Soft-tissue syndromes

and Degenerative

disorders

Fibromyalgia, Polyarticular

osteoarthritis

Deposition disorders Hemochromatosis

Malignancy

(paraneoplastic

syndromes)

Lung cancer, Multiple myeloma

937 Majithia and Geraci RA: Systemic, Inammatory Disease

fying antirheumatic drugs may be more effective than sin-

gle-drug regimens.

3

Women of childbearing age should use

adequate contraception when taking certain (teratogenic)

disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (Table 3).

Biologics, the latest generation of antirheumatic drugs,

have novel molecular mechanisms that target cytokines,

signaling molecules and cells involved in inammation and

joint destruction. These include the tumor necrosis factor

antagonists: adalimumab, etanercept, and iniximab (rst

line agents); the Interleukin-1 antagonist, anakinra; the

anti-B cell antibody, rituximab; and the down-regulator of

T-cell co-stimulation, abatacept. All biologics are associ-

ated with an increased risk of infection (bacterial, viral, and

fungal) and tuberculosis reactivation. Table 3 lists disease-

modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic dosing regi-

mens, times to onset of benet, adverse effects, and safety

monitoring.

3

It is important to note that there is disagreement among

rheumatologists about the choice of initial therapy. There is

evidence that combination of methotrexate and a biologic

agent is the most effective current therapy but the short- and

long-term risks, as well as the cost-effectiveness of biologic

agents, are not well dened.

3

Due to these unanswered

questions, common rheumatology practice is to begin meth-

otrexate alone as initial therapy.

Chronic treatment of rheumatoid arthritis is a continuous

process, and periodic patient re-assessment is paramount.

Patients should be evaluated every 2-3 months for control of

Table 3 Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment: Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs and Biologic Agents

Drug Dosage

Onset of

Effect Adverse Events Monitoring

Abatacept 500-1000 mg (weight

based) at 0, 2 and

4 weeks then every

4 weeks

2-12 weeks ISR, infections, hypersensitivity,

COPD exacerbation

Monitor for TB, other infections;

CBC, chemistry and LFTs at

baseline and with each

infusion

Adalimumab 40 mg sc biweekly 2-12 weeks ISR, infections, TBr;

demyelinating disorders (rare)

TB, fungal, other infections; CBC

and LFTs at baseline and then

every 2-3 months

Anakinra 100 mg sc daily 4-12 weeks ISR, leucopenia, infections,

hypersensitivity

CBC at baseline and every 3

months

Azathioprine 50-150 mg po daily 2-3 months GI intolerance, cytopenia,

hepatitis, infections

CBC, LFTs every 2-4 weeks

initially, then every 2-3

months

Cyclosporine 2.5-5 mg po daily 2-3 months GI intolerance, cytopenia,

infections, hypertension, renal

disease

Cr every 2 weeks at initiation,

then monthly; consider CBC,

LFTs, and K

Etanercept 25 mg sc twice/ week

or 50 mg sc weekly

2-12 weeks ISR, infections, TBr;

demyelinating disorders (rare)

TB, fungal, other infections; CBC

and LFTs at baseline and then

every 2-3 months

Hydroxychloroquine 200-400 mg po daily 2-6 months GI intolerance, Retinal toxicity Fundoscopy every 12 months

Iniximab 3 mg/kg at weeks 0,

2 and 4, then

every 8 weeks

2-12 weeks ISR, infection, TBr;

demyelinating disorders (rare)

TB, fungal, other infections; CBC

and LFTs at baseline and then

every 2-3 months

Leunomide 20 mg daily 4-12 weeks GI intolerance, skin rash,

hepatitis, cytopenia; highly

teratogenic

Hepatitis B and C serology in

high-risk patients; CBC, Cr and

LFTs monthly x6, then every

1-2 months; reduce dose or

stop if LFTs elevate

Methotrexate 15-25 mg orally, sc

or IM weekly

1-2 months GI intolerance, oral ulcers,

alopecia, hepatitis,

pneumonitis, cytopenia, rash;

teratogenic

CBC, Cr and LFTs monthly x6,

then every 1-2 months; adjust

dose or stop if LFTs elevate

Minocycline 100 mg twice daily 1-3 months Dizziness, skin pigmentation none

Rituximab 1000 mg at 0 and 15

days

2-12 weeks ISR, infection risk, new and

reactivation viral infections,

respiratory difculty,

cytopenia

Monitor for TB, other infections;

CBC, chemistry and LFTs at

baseline and 2 weeks, every

2-3 months thereafter

Sulfasalazine 2-3 gm daily 1-3 months GI intolerance, oral ulcers,

cytopenia, rash

CBC every 2-3 months

Sc subcutaneous; po orally; imintramuscularly; ISR injection site reaction; CBC complete blood count; LFTs liver function tests;

UA urinalysis with microscopic examination; Cr serum creatinine; TBr tuberculosis reactivation.

938 The American Journal of Medicine, Vol 120, No 11, November 2007

disease activity, extra-articular manifestations, medication

side effects, and functional capacity. Annual hand and feet

radiographs (for joint surface erosions and demineraliza-

tion) also are recommended.

3

KEY POINTS: MANAGEMENT

In managing chronic rheumatoid arthritis, the primary care

physician should assess course (improvement or progres-

sion), net disability, and medication side effects (including

osteoporosis with chronic steroid use). Ongoing surveil-

lance for infection, tuberculosis, and malignancy (age-ap-

propriate screening), osteoporosis and immunizations (in-

uenza vaccine and pneumovax) are essential components

of care. Cardiovascular risk factor reduction is warranted

due to a higher risk for development of coronary artery

disease related to the underlying disease or medications.

SUMMARY

Prompt and accurate diagnosis, early aggressive treatment,

including disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs or biolog-

ics, symptom control, and close monitoring of disease state

and medication toxicity are the keys to effective manage-

ment of the patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Subspecialty

referral should be considered in all patients with moderate-

severe disease or demonstrating incomplete response.

References

1. Harris ED. Clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Kelleys Text-

book of Rheumatology, 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders; 2005:

1043-1078.

2. Firestein GS. Etiology and pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. In:

Kelleys Textbook of Rheumatology, 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B.

Saunders; 2005:996-1042.

3. American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid

Arthritis Guidelines. Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid

arthritis: 2002 update. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:328-346.

4. Van-Gaalen FA, Linn-Rasker SP, van Venrooij WJ, et al. Autoantibod-

ies to cyclic citrullinated peptides predict progression to rheumatoid

arthritis in patients with undifferentiated arthritis: a prospective cohort

study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(3):709-715.

5. Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism

Association 1987 revised criteria for the classication of rheumatoid

arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315-324.

939 Majithia and Geraci RA: Systemic, Inammatory Disease

You might also like

- Chronic Virus Report of Three Cases Indolent Orofacial Herpes Simplex Infection in Chronic Leukemia: ADocument4 pagesChronic Virus Report of Three Cases Indolent Orofacial Herpes Simplex Infection in Chronic Leukemia: ANatalia RafaelNo ratings yet

- P1D 15 Playground Colors PDFDocument1 pageP1D 15 Playground Colors PDFNatalia RafaelNo ratings yet

- Pagina 324Document8 pagesPagina 324Natalia RafaelNo ratings yet

- 21 CFR 56 Comite de Revision Institucional 1998Document12 pages21 CFR 56 Comite de Revision Institucional 1998Natalia RafaelNo ratings yet

- Enf de Chron GuidelinesDocument11 pagesEnf de Chron GuidelinesNatalia RafaelNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- History TakingDocument4 pagesHistory TakingaliNo ratings yet

- Evaluation & Management CodingDocument14 pagesEvaluation & Management Codingsherrij1025No ratings yet

- Eng PDFDocument45 pagesEng PDFEll TabokomNo ratings yet

- Mod 6 CommunicationDocument43 pagesMod 6 CommunicationAhmad FarooqNo ratings yet

- Community Health NursingDocument2 pagesCommunity Health NursingCharissa Magistrado De LeonNo ratings yet

- English For The Professional NurseDocument12 pagesEnglish For The Professional NurseOryza SativaNo ratings yet

- Hyperemesis Gravidarum: Kelompok 5 Andi Cipta Andi Salma Vadhila Nur Alia Resmi Julita Putri RismayantiDocument7 pagesHyperemesis Gravidarum: Kelompok 5 Andi Cipta Andi Salma Vadhila Nur Alia Resmi Julita Putri RismayantiChayeol ParkNo ratings yet

- Nutrition - Dietetics CpdprogramDocument1 pageNutrition - Dietetics CpdprogramPRC BoardNo ratings yet

- Jason Christopher DecDocument71 pagesJason Christopher DecDave MinskyNo ratings yet

- Health Care Delivery SystemDocument40 pagesHealth Care Delivery SystemBhumika100% (1)

- CITY STAR November 2016 EditionDocument20 pagesCITY STAR November 2016 Editioncity star newspaperNo ratings yet

- JD RBSK DeicDocument2 pagesJD RBSK DeicAjay UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- General Competency Radiology In-Training Test Questions For Diagnostic Radiology ResidentsDocument9 pagesGeneral Competency Radiology In-Training Test Questions For Diagnostic Radiology ResidentsSabinaNo ratings yet

- Health Disparity and Literacy PaperDocument5 pagesHealth Disparity and Literacy PaperlameckwesiNo ratings yet

- Aspects of Early Movement Therapy in Line With The Medical DiagnosisDocument2 pagesAspects of Early Movement Therapy in Line With The Medical DiagnosisHajduGrétaNo ratings yet

- Susarla - Pediatric TraumaDocument1 pageSusarla - Pediatric TraumaRicardo GrilloNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Transplant Rating InstrumentDocument10 pagesPediatric Transplant Rating InstrumentcoxalfonsoNo ratings yet

- HE Teaching PlanDocument6 pagesHE Teaching PlanAiza ToledanaNo ratings yet

- Letter To B.C. Health MinisterDocument3 pagesLetter To B.C. Health MinisterThe Globe and MailNo ratings yet

- Canadanian Jurnal Diabetes PDFDocument342 pagesCanadanian Jurnal Diabetes PDFdyahNo ratings yet

- Ashley M Hannah - Resume 2017Document2 pagesAshley M Hannah - Resume 2017api-358481330No ratings yet

- C CCCCCCCCCCCC C C C CDocument20 pagesC CCCCCCCCCCCC C C C CZandra Kiamco MillezaNo ratings yet

- Arp2017 5627062Document6 pagesArp2017 5627062Syamsi KubangunNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan Cholecystectomy Gall Bladder RemovalDocument2 pagesNursing Care Plan Cholecystectomy Gall Bladder Removalderic100% (16)

- Ambuja Cement Foundation Visit ReportDocument5 pagesAmbuja Cement Foundation Visit ReportRavisinh ValaNo ratings yet

- HHMT Declaration Form Jan 14Document8 pagesHHMT Declaration Form Jan 14api-248499989No ratings yet

- Unit 3 Module Networking TemplateDocument17 pagesUnit 3 Module Networking Templateapi-562162979No ratings yet

- PEJC Prelim X Midterm ReviewerDocument20 pagesPEJC Prelim X Midterm Reviewerjessamae.bucad.cvtNo ratings yet

- Teaching PlanDocument2 pagesTeaching PlanalyNo ratings yet

- Course Code Description Units Pre-Requisite: Obe CurriculumDocument2 pagesCourse Code Description Units Pre-Requisite: Obe CurriculumShyla ManguiatNo ratings yet