Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2 Is Speeding A Real Antisocial Behav

Uploaded by

Edit RomanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2 Is Speeding A Real Antisocial Behav

Uploaded by

Edit RomanCopyright:

Available Formats

Accident Analysis and Prevention 39 (2007) 384389

Is speeding a real antisocial behavior? A comparison with

other antisocial behaviors

Damian R. Poulter, Frank P. McKenna

School of Psychology, University of Reading, Reading, Berkshire RG6 6AL, UK

Received 22 May 2006; received in revised form 20 July 2006; accepted 20 August 2006

Abstract

The relationship between speed and crashes has been well established in the literature, with the consequence that speed reduction through enforced

or other means should lead to a reduction in crashes. The extent to which the public regard speeding as a problem that requires enforcement is less

clear. Analysis was conducted on public perceptions of antisocial behaviors including speeding trafc. The data was collected as part of the British

Crime Survey, a face-to-face interview with UK residents on issues relating to crime. The antisocial behavior section required participants to state

the degree to which they perceived 16 antisocial behaviors to be a problem in their area. Results revealed that speeding trafc was perceived as the

greatest problem in local communities, regardless of whether respondents were male or female, young, middle aged, or old. The rating of speeding

trafc as the greatest problem in the community was replicated in a second, smaller postal survey, where respondents also provided strong support

for enforcement on residential roads, and indicated that traveling immediately above the speed limit on residential roads was unacceptable. Results

are discussed in relation to practical implications for speed enforcement, and the prioritization of limited police resources.

2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Speeding; Attitudes; Antisocial behavior

1. Introduction

Within professional circles the overall relationship between

speed and road crashes is uncontroversial (e.g., Aarts and van

Schagen, 2006; Finch et al., 1994; Richter et al., 2006). One

conclusion that obviously follows is that speed reduction, for

example through enforcement, should be effective in reducing

crashes. One conclusion that does not obviously follow is the

extent to which the public regard speeding as a problem that

merits enforcement. It is likely that an effective overall strat-

egy will require not only effective speed enforcement but also

a public that is concerned about speeding. We will argue that

without the latter, policy makers may not sanction the former.

At a practical level winning public support is a critical factor in

successful speed enforcement programs (Delaney et al., 2005b).

One efcient enforcement strategy has been the use of cam-

eras that automatically record speed choices. The use of safety

cameras to enforce speed limits has become common in some

parts of the world (Delaney et al., 2005b). For example, in Eng-

Corresponding author. Tel.: +44 118 378 8530; fax: +44 118 378 6715.

E-mail address: f.p.mckenna@rdg.ac.uk (F.P. McKenna).

land and Wales 91% of speeding offences are now detected by

cameras (Fiti and Murray, 2006). Cameras also have demonstra-

ble safety benets in terms of both vehicle speed reduction and

crash reduction (Chen et al., 2000; Gains et al., 2005; Retting

and Farmer, 2003). Despite the scientic evidence to support

the use of automated speed enforcement, there has been con-

siderable public debate. The importance of this debate has been

witnessed in Canada, where an automated speed enforcement

program in British Columbia was terminated following lobby-

ing by interest groups (Delaney et al., 2005a).

1.1. Media representation of speeding

In some countries where the use of cameras has been com-

mon, such as in Britain, there has been a discrepancy between the

national and local newspaper coverage. The reporting of cam-

eras in the local community where the camera has been placed

has generally been more positive than in the national newspapers

(Delaney et al., 2005a). For example, some parts of the national

media in Britain have taken an anti-camera stance, with con-

tinuing criticisms that the motorist is being targeted rather than

real criminals. In the Daily Mail newspaper the shadow Home

Secretary, David Davis, was quoted saying, This huge increase

0001-4575/$ see front matter 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.aap.2006.08.015

D.R. Poulter, F.P. McKenna / Accident Analysis and Prevention 39 (2007) 384389 385

in summary motoring offences shows the police are focusing too

much on motorists and not enough on catching serious criminals.

This has to change (Slack and Massey, 2005). In the Telegraph,

former Home Ofce minister, Anne Widdicombe, was reported

to argue for police prioritizing tackling burglars and other crim-

inals, rather than pursuing motorists, and was quoted to say, If

police pull over a motorist for hogging a middle lane, they may

well be asked about the progress they have made nding the bur-

glar that visited the motorists house. It would be a legitimate

question, given that the police have limited resources, and have

to prioritize their work (Day, 2004). Newspaper columnists

often use their platform to further the notion that the motorist

is unfairly penalized, The police cant catch criminals. So they

criminalize motorists instead . . . the two million drivers who

get done every year are the poor saps who do everything that

society asks them toapart from keeping to often absurdly low

speed limits . . . why are the police treating the average motorist

as a criminal? Because catching real criminals is beyond them

(Parsons, 2003).

1.2. Public attitudes to speeding and automated speed

enforcement

In other areas of national debate, research shows that news

media exerts a considerable inuence on the formation of public

opinion (e.g., Gamson and Modigliani, 1989). While national

media has tended to claimthat speeding is less serious in relation

to other crimes, and is largely anti-speed enforcement, it is less

clear whether this accurately reects public opinion.

In contrast to media representations, research on public atti-

tudes towards speed and speed enforcement has, on average,

been positive. In the United States, in a telephone survey of 500

residents in Washington, DC, 9 months after the start of a speed

camera enforcement program, residents were askedwhether they

thought speeding drivers were a problem in the district (Retting,

2003). Results showed that almost two-thirds of residents felt

speeding motorists were a problem (64%), with a greater per-

centage of drivers aged 60 years and older perceiving speeding

motorists as a problem (81%) than drivers aged 3059 (65%)

and 1829 (52%). With regards to speed enforcement, other

telephone surveys of communities where photo-radar enforce-

ment had been conducted or was being proposed revealed that

public acceptance of cameras was just under 60%, with disap-

proval at around 3540% (Freedman et al., 1990; Lynn et al.,

1992). In the Lynn et al. (1992) study, a greater percentage of

females (73.2%) reportedapproval for the proposedenforcement

than males (54.3%). Retting (2003) notes that overall support

for speed cameras (51%) was lower in his study than in the

Freedman et al. (1990) and the Lynn et al. (1992) studies, but

explains that this could in part be explained by a relatively high

percentage of respondents (56%) who had received, or knew

someone who had received a speeding ticket since the cam-

eras were in operation. Overall the Freedman et al. (1990) study

reported only 25% of drivers had received a ticket in the previ-

ous 3 years, and in the Lynn et al. (1992) study the speed cameras

were not yet installed.

As previously mentioned, automated speed enforcement is

more widespreadinAustralia andEurope thaninNorthAmerica,

and public opinion surveys have largely focused on attitudes

towards speed enforcement. Telephone surveys of Australians

have found a majority support (over 85%) for at least no change

or an increase in current levels of speed enforcement (Pennay,

2005; Mitchell-Taverner et al., 2003). Pennay (2005) found that

more females (46%) than males (31%) supported an increase in

the level of enforcement, and, less expected, more support for an

increase in enforcement by 1524-year-olds (43%), compared

to the 2539-year-olds (39%), the 4059-year-olds (38%), and

the 60+-year-olds (36%).

A European survey using face-to-face interviews on social

attitudes to road trafc risk with just over 24,000 car drivers in

23 European countries found a high degree of public support for

enforcement, with 76%of drivers in favor of more enforcement,

and just over 60% agreeing or strongly agreeing that penalties

for speeding should be more severe (SARTRE, 2004).

In Britain alone, an extensive survey of driving behavior

revealed that the majority of drivers thought the 30 mph speed

limit in towns were set at the correct speed (+80%), with a third

of drivers thinking the 30 mph speed limit in narrow residen-

tial streets was too high (Stradling et al., 2003). Approximately

50% of drivers thought speed limits on 30 mph roads should

not be broken at all, 79% thought the current penalty for speed-

ing was about right or too lenient, and 75% supported use of

speed cameras to enforce speed limits (Stradling et al., 2003). In

response to claims by opponents that speed cameras are deeply

unpopular, the Parliamentary Advisory Council for Transport

Safety (PACTS, 2003) reported that opinion polls generally nd

widespread public support for speed cameras (e.g., Gains et

al., 2005; Transport 2000, 2003). However, within government

there is evidence of a persisting perception that speed cam-

eras are controversial, with the Parliamentary Ofce of Science

and Technology (2004) stating, public attitudes to speed cam-

eras are mixed. The Parliamentary postnote continues, there

is widespread public and media debate about speed camera

effectiveness and the motives for their use. Experience overseas

indicate that public support is crucial to the success of speed

camera schemes.

1.3. Speed limit compliance

Before addressing public perception of speed, it is worth con-

sidering actual speed behavior, and levels of non-compliance on

roads, in particular urban roads. Non-compliance in the follow-

ing incidences refers to all vehicles traveling above the posted

speed limit, regardless of whether it is a minor or major infrac-

tion. Harkey et al. (1990) assessed speed characteristics and

compliance with posted limits for free-owing vehicles on road-

ways from 25 to 55 mph in four US states, and found that for

30 mph roads non-compliance with the speed limit was 76%.

More recently, in an investigation of the effectiveness of speed

reduction techniques in high density pedestrian areas in Min-

nesota, USA, Kamyab et al. (2002) found that 64% of vehicles

were exceeding the 30 mph speed limit prior to speed reduction

interventions taking place.

386 D.R. Poulter, F.P. McKenna / Accident Analysis and Prevention 39 (2007) 384389

A report by the European Transport Safety Council (1995)

detailed speed limit compliance across European countries, cit-

ing the percentage of cars exceeding the speed limit on 50 km/h

(31 mph) urban roads as 64%in France (ONSR, 1994), and 71%

in Spain (DGT, 1993). For the UK the percentage breaking the

30 mph speed limit was 50% (Department for Transport, 2006).

The evidence from driving behavior on urban roads across

countries, therefore, demonstrates that non-compliance with the

speed limit is high. This is coupled with public support for

speed reduction via enforcement as discussed earlier. What is

less known is the public perception of speeding in relation to

other antisocial behaviors.

1.4. Aims

Within the scientic literature the focus has largely been

on public attitudes to speed enforcement, and there has been

a lack of research on public attitudes to speeding in relation to

other community problems. Hence there is a lack of perspective

regarding the extent to which people perceive speeding motorists

to be a problem in comparison with other antisocial behavior in

the local community. If, as noted in the literature (a) the pri-

oritizing of police resources is an issue for public debate, and,

(b) public support for speed enforcement is a key element in

successful programs (Delaney et al., 2005b), then it would be

useful to determine how the public perceive the issue of speed-

ing relative to other forms of antisocial behavior. Attitudes to

speeding trafc and other antisocial behaviors were analyzed

from the latest British Crime Survey data (20032004). Given

the gender effects reported in attitude surveys earlier in the intro-

duction, coupled with the literature on gender differences in

driving behavior (e.g., Byrnes et al., 1999; French et al., 1993),

it was expected that females would rate speeding trafc as a

greater problem than males would. Likewise it was predicted

that older respondents would rate speeding as a greater problem

than younger respondents (French et al., 1993).

In addition to the analysis on the antisocial behavior data

from the BCS a smaller postal survey was conducted using an

alternative method to the BCS where antisocial behaviors were

generated by local communities in a pilot survey. This was done

in case behaviors in the BCSwere prescriptive and did not reect

antisocial behaviors as perceived by respondents. Fromthis data

the top 10 issues ranked as most problematic in the communities

were selected for the postal survey. Furthermore, the second sur-

vey included two items regarding attitudes towards speed limit

compliance and speed limit enforcement that were not present

in the BCS.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Analysis was conducted on survey data on perceptions of

antisocial behavior problems in the 20032004 BCS. Full details

of the survey design and measure are available from the Home

Ofce (2006). Briey, the 20032004 BCS is based on a rep-

resentative sample of 37,213 adults aged 16 and over in pri-

vate households in England and Wales between April 2003 and

March 2004 (response rate at initial telephone contact =74.1%).

Sampling was conducted using a multi-stage stratied random

sample, with the small user Postcode Address File used as the

general population sampling frame. Stratication was done by

Police Force Area, population density, and the proportion of

household heads in non-manual occupations.

One addition to the 20032004 BCS from previous years

was the new module on antisocial behavior, with the inclusion

of the item on speeding trafc. For the complete 16 items relat-

ing to perceptions of problems in local communities, a total

of 16,593 participants responded. For the speeding trafc item

alone, gender analysis included responses from 17,869 partici-

pants (male:female =7935:9934), and for age analysis there was

a total of 17,851 responses, spread across three age groups,

1629 years (n =2629), 3059 years (n =9374), and 60+ years

(n =5848).

In addition, a second postal survey was conducted in two local

communities in England. A total of 4200 questionnaires were

delivered by hand to all households in the two communities, with

a return rate of 29.0%, of which 1125 participants responded to

all 10 antisocial behavior items.

2.2. Procedure

The 20032004 BCS was a face-to-face survey of people

aged 16 and over living in private households in England and

Wales, conducted in peoples own household by an interviewer,

and included a variety of topics relating to their experience

of, and attitudes towards crime. For the module on antiso-

cial behavior, participants were asked to rate the degree to

which they perceived 16 antisocial behaviors to be a prob-

lem. The 16 antisocial behaviors included noisy neighbors or

loud parties (noisy neighbors), teenagers hanging around on

the streets (teenagers), people sleeping rough on the streets

or in other public places (rough sleepers), rubbish or litter

lying around (rubbish), vandalism, grafti and other delib-

erate damage to property and vehicles (vandalism/grafti),

people being attacked or harassed because of their skin color,

ethnic origin or religion (race attack), people using or dealing

drugs (drugs), people being drunk or rowdy in public places

(drunk), abandoned or burnt out cars (abandoned cars), peo-

ple being insulted, pestered or intimidated in the street (pes-

tering) uncontrolled dogs and dog mess (dogs), conicts or

disputes between neighbors (neighbor dispute), cars parked

inconveniently, dangerously or illegally (parked cars), re-

works being set off that are not part of an organized display

(reworks), people using or carrying airguns or replica guns

(airgun), and speeding trafc (speeding trafc). Participants

were asked to rate the degree to which they perceived each

antisocial behavior as a problem in their area, dened as an

area 15 min walk from their house, on a Likert scale from 1

to 4 (1 =not a problem at all; 2 =not a very big problem;

3 =fairly big problem; 4 =very big problem). Specic analy-

sis was conducted on ratings for the speeding trafc itemalone,

in order to explore any potential gender and age differences in

ratings.

D.R. Poulter, F.P. McKenna / Accident Analysis and Prevention 39 (2007) 384389 387

With regard to the postal survey, data from a pilot survey

revealed that the highest ranked problems in two local com-

munities were as follows: antisocial behavior from children or

youths, burglary, drug abuse/drug dealing, fear of going out at

night, y tipping, litter, noise at night, speeding motorists, under-

age drinking, and vandalism/criminal damage. These problems

largely overlapped with items in the British Crime Survey, with

the exception of burglary, fear of going out at night, and y

tipping. Fear of going out at night is not an antisocial behav-

ior per se, more a factor related to antisocial behavior, but was

included due to its selection by respondents in the pilot study.

Participants were required to rate their level of concern on a

Likert scale from 1 to 5 (1 =not at all concerned, 2 =a little con-

cerned, 3 =concerned, 4 =quite concerned, 5 =very concerned)

for all 10 problems. This was followed by two questions relat-

ing to driving behavior in relation to speed limits and speed

enforcement. Participants were asked to rate the extent to which

they agreed with the statements It is acceptable to drive down

30 mph residential streets at 35 mph, and it is acceptable to

enforce speed limits on 30 mph residential streets, again on a

ve point Likert scale (1 =totally disagree, to 5 =totally agree).

One member of each household was asked to complete the ques-

tionnaire in their own time before returning it by post. Afreepost

envelope was included with the questionnaire. All participants

were informed that the research teamwould be unable to identify

them from the information provided.

3. Results

An alpha level of .05 was used to determine statistical signif-

icance. Partial eta-squared (

2

p

) was calculated to indicate effect

size.

3.1. British Crime Surveyperceptions of antisocial

behavior

An initial comparison was made of rating of speeding traf-

c by vehicle owners (n =13,116) and non-vehicle owners

(n =3477). Vehicle owners ratings of speeding trafc as a prob-

lem (M=2.34, S.D. =0.96) were higher than non-vehicle own-

ers (M=2.20, S.D. =1.01). An independent t-test revealed this

difference was signicant (t(6066.62) =8.06, p <.05, 95% CI:

0.110.18). Both vehicle owners and non-vehicle owners gave

speeding trafc a signicantly higher rating than any other prob-

lem (p <.05), and therefore data was collapsed across the two

groups for the main analysis.

Overall, the problem given the highest average rating was

speeding trafc (M=2.30, S.D. =0.97), followed by rubbish

(M=2.03, S.D. =0.92), parked cars (M=2.02, S.D. =0.95),

and vandalism (M=1.98, S.D. =0.89).

Mauchlys test of sphericity revealed that the error covari-

ance matrix of the orthonormailised transformed dependent vari-

ables was not proportional to an identity matrix (W(119) =.15,

p <.01), and thus a Greenhouse-Geisser adjusted F-value was

adopted.

A repeated measures ANOVA (problem: noisy neighbors,

teenagers, rough sleeping, rubbish, vandalism, race attack,

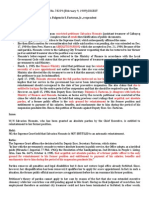

Fig. 1. Mean ratings for perceptions of all 16 types of behavior as a problem

on a scale from 1 to 4 (1 =not a problem at all, to 4 =a very big problem), with

95% condence interval bars.

drugs, drunk, abandoned cars, pestering, dogs, neighbor dis-

pute, parked cars, reworks, airguns, speeding trafc) was con-

ducted on participants rating of problems. Results revealed a

main effect of Problem (F(13, 2000695.5) =4252.07, p <.01,

2

p

=.20). Post hoc within-participants contrasts showed that

speeding trafc was signicantly greater than any other prob-

lem (p <.01). Results are displayed in Fig. 1.

An a priori independent t-test was conducted on ratings of

how much speeding trafc was perceived as a problem by

males (M=2.30, S.D. =0.95) and females (M=2.32, S.D. =.99).

Results revealed a non-signicant difference between males and

females (t(17277.567) =1.29, p =.20, 95% CI: 0.050.01). It

should also be noted that speeding motorists were rated higher

than all other antisocial behaviors by both males and females.

An a priori one-way ANOVA(age: 1629 years, 3059 years,

60+ years) on ratings of speeding trafc as a problem revealed

a signicant main effect of Age (F(2, 17,848) =71.55, p <.01,

2

p

=.01). Post hoc Tukey tests revealed that the 3059 years

group and the 1629 years group both rated speeding trafc

signicantly higher than the 60+ group (p =.01), but there was

no signicant difference between the 3059 years group and the

1629 years group (p =.08). Results are presented in Fig. 2. It

Fig. 2. Mean ratings for perceptions of speeding trafc as a problem by age

group (1629 years, 3059 years, 60+ years), with 95% condence interval

bars.

388 D.R. Poulter, F.P. McKenna / Accident Analysis and Prevention 39 (2007) 384389

should also be noted that all three age groups rated speeding

motorists higher than any other problem.

3.2. Postal survey of local community problems

Results of the postal survey replicated ndings fromthe BCS.

A repeated measures ANOVA (problem: antisocial behavior

from children or youths, burglary, drug abuse/drug dealing, fear

of going out at night, y tipping, litter, noise at night, speed-

ing motorists, under-age drinking, vandalism/criminal damage)

revealed a signicant difference in ratings of problems in the

community (F(7.54, 8471.25) =162.19, p <.01,

2

p

=.13), with

post hoc analysis showingspeedingmotorists ratedas the prob-

lemof most concern, signicantlygreater thanall other problems

(p <.01).

Independent t-tests on male and female ratings for the

two items relating to driver behavior with regards to speed

limits and speed enforcement were conducted. For the state-

ment It is acceptable to drive down 30 mph residential streets

at 35 mph, female participants (M=1.76, S.D. =0.98) rated

themselves as disagreeing with it to a greater degree than

male participants (M=1.94, S.D. =1.05). An independent t-

test revealed that this difference was signicant (t(1194) =3.14,

p <.01, 95% CI: 0.070.30). Female participants (M=4.35,

S.D. =0.91) rated themselves as agreeing with the statement

it is acceptable to enforce speed limits on 30 mph residential

streets more so than male participants (M=4.19, S.D. =0.98).

An independent t-test revealed that this difference was signi-

cant (t(1196) =2.82, p <.01, 95% CI: 0.050.26). Both females

and males rated themselves between 4: agree and 5: totally

agree.

4. Discussion

Law enforcement can present authorities with a dilemma.

Suppose that the majority of the population break a law. What

mandate do authorities have for imposing on the majority of

the people that they represent, a law that the majority break?

Examining the public mandate may be worthwhile in these cir-

cumstances. At a practical level it has been argued that public

debate can and has led to the collapse of an enforcement program

(Delaney et al., 2005a). What then informs this public debate?

While authorities may infer public opinion fromthe media there

are times when the media may not present authorities with an

accurate reection of public concern. In the case of speeding it

is not clear that the media have captured public concern. Indeed

analysis of data on public perceptions of antisocial behavior in

the latest British Crime Survey revealed that speeding trafc

is rated as the greatest problem in local communities. Males

and females both rated speeding trafc with the same degree

of concern, with 3059-year-olds and 1629-year-olds rating

it higher than the 60+ age group. Even when conducting anal-

ysis on the sub-groups, speeding trafc consistently came out

as the antisocial behavior perceived to be the greatest problem,

whether respondents were male or female, young, middle aged,

or old.

In contrast to previous research (e.g., Pennay, 2005; Lynn et

al., 1992) there was no signicant gender difference in the con-

cern for speeding trafc in the BCS. However, the gender differ-

ence was signicant in the second survey, with females reporting

greater support for speed limit compliance and endorsement of

speed limit enforcement than males did. With regards to age

effects, the nding that the younger age groups (1629 years,

3059 years) rated speeding trafc higher than the 60+ years

group contrasts with previous literature where older respon-

dents perceive speeding as a greater problem than their younger

counterparts (Retting, 2003). It should be noted that over half

the respondents in the Retting study had previously received a

ticket for speeding. The reverse trend found in our study could be

attributable to two factors: that the overall proportion of respon-

dents with speeding tickets differed between the two samples;

or, that the distribution of speeding tickets within each sample

was different across age groups. Unfortunately, data on speed-

ing tickets was unavailable in the BCS, and the distribution of

tickets across age groups in the Retting study was not reported.

On the basis of current results the police could argue that

any enforcement programcurrently operating is compatible with

public concern. As noted in the introduction there is an issue of

prioritizing limited police resources. Clearly if these were to be

allocated as a function of public concern then speed enforcement

in the UK would be considerable. It might be argued, however,

that voicing a concern does not automatically mean support for

enforcement. Two points are worth noting. The rst addresses

the issue of support for enforcement. We found that people did

support enforcement on 30 mph residential roads and did indi-

cate that traveling at 35 mph on a 30 mph residential road was not

acceptable. This is in line with previous evidence that the pub-

lic accept the practice of speed enforcement (e.g., Gains et al.,

2005; Lynn et al., 1992; Mitchell-Taverner et al., 2003; Pennay,

2005). The second point is that concern about speeding could

be realized through means other than enforcement. For exam-

ple, trafc engineering or instruments such as Speed Indication

Devices, which provide feedback rather than enforcement, could

be employed.

The potential contrast between concerns expressed about

speeding and action on the road is of interest. It is not entirely

clear whether those who express most concern about speeding

are different from those who actually speed. It is possible that

those who express concern about speeding do so in both their

attitudes and their behavior. Alternatively it is entirely possible

that peoples concern about speeding reects what they feel

they ought to do rather than what they actually do. Interestingly,

the percentage of drivers breaking the speed limit is decreasing.

In 1998 70% were observed to break the 30 mph speed limit

whereas in 2005 this gure has come down to 50% (Department

for Transport (2006). An important challenge for authorities

is how to deal with the concern that the public express about

speeding.

Acknowledgements

Material from Crown copyright records made available

through the Home Ofce and the UK Data Archive has been

D.R. Poulter, F.P. McKenna / Accident Analysis and Prevention 39 (2007) 384389 389

used by permission of the Controller of Her Majestys Sta-

tionery Ofce and the Queens Printer for Scotland. This work

was funded in part by the Thames Valley Police as part of an

ongoing research program. We would also like to thank Thames

Valley Safer Roads Partnership for their co-operation.

References

Aarts, L., van Schagen, I., 2006. Driving speed and the risk of road crashes: a

review. Accid. Anal. Prevent. 38, 215224.

Byrnes, J.P., Miller, D.C., Schafer, W.D., 1999. Gender differences in risk taking:

a meta-analysis. Psych. Bull. 125 (3), 367383.

Chen, G., Wilson, J., Meckle, W., Cooper, P., 2000. Evaluation of photo radar

in British Columbia. Accid. Anal. Prevent. 32, 517526.

Day, E., 2004. Prosecute motorway lane hogs, RAC says. http://www.telegraph.

co.uk/news/.

Delaney, A., Ward, H., Cameron, M., 2005a. The history and development of

speed camera use. Monash University Accident Research Centre, Report

No. 242.

Delaney, A., Ward, H., Cameron, M., Williams, A.F., 2005b. Controversies and

speed cameras: lessons learnt internationally. J. Public Health Policy 26 (4),

404415.

Department for Transport, 2006. Transport Statistics Bulletin: Vehicle Speeds

in Great Britain 2005. Department for Transport, London, UK.

DGT, Direccion General De Traco, 1993. Annuario estadistico general, Direc-

cion General De Traco, Madrid.

European Transport Safety Council, 1995. Reducing trafc injuries resulting

from excess and inappropriate speed, Brussels: European Transport Safety

Council. http://www.etsc.be/.

Finch, D.J., Kompfner, P., Lockwood, C.R., Maycock, G., 1994. Speed, speed

limits and crashes. Project Record S211G/RB/Project Report PR 58, Trans-

port Research Laboratory TRL, Crowthorne, Berkshire.

Fiti, R., Murray, L., 2006. Motoring offences and breath test statis-

tics: England and Wales 2004, Home Ofce Statistical Bulletin 05/06,

www.homeofce.gov.uk/rds.

Freedman, M., Williams, A.F., Lund, A.K., 1990. Public opinion regarding photo

radar. Transportation Research Record 1270, TRB, Washington, DC, pp.

5965.

French, D.J., West, R.J., Elander, J., Wilding, J.M., 1993. Decision making

style, driving style and self-reported involvement in road trafc accidents.

Ergonomics 36, 627644.

Gains, A., Nordstrom, M., Heydecker, B., Shrewsbury, J., Mountain, L., Maher,

M., 2005. The National Safety Camera Programme: Four-year Evaluation

Report. PA Consulting Group, UCL, University of Liverpool, and Napier

University.

Gamson, N.A., Modigliani, A., 1989. Media discourse and public opinion on

nuclear power: a constructivist approach. Am. J. Soc. 95, 137.

Harkey, D.L., Robertson, H.D., Davis, S.E., 1990. Assessment of current

speed zoning criteria. Transportation Research Record, 1281. Transporta-

tion Research Board, Washington, DC.

Home Ofce, 2006. Research and Statistics Directorate and BMRB. Social

Research, British Crime Survey, 20032004 (computer le). Colchester,

Essex, UK Data Archive (distributor). SN: 5324.

Kamyab, A., Andrle, S., Kroger, D., 2002. Methods to reduce trafc speed in

high pedestrian areas. Report no. MN/RC-2002-18. Minnesota Department

of Transport, St. Pauls, Minnesota.

Lynn, C.W., Garber, N.J., Ferguson, W.S., Lienau, T.K., Lau, R., Alcee, J.V.,

Black, J.C., Wendzel, P.M., 1992. Automated Speed Enforcement Pilot

Project for the Capital Beltway: Feasibility of Photo Radar. Virginia Trans-

port Research Council, Charlottesville, VA.

Mitchell-Taverner, P., Zipparo, L., Goldsworthy, J., 2003. Survey on speeding

and enforcement. Report no. CR214a, Australian Transport Safety Bureau,

ACT, Australia.

ONSR, Observatoire National Interministerial de Securite Routiere, 1994. Bilan

annuel statistiques et commentariesannee 1993. Arcueil: Observatoire

National Interministerial de Securite Routiere.

Parliamentary Advisory Council for Transport Safety and the Slower Speed

Initiative, 2003. Speed Cameras: 10 criticisms and why they are awed.

Research brieng, December 2003.

Parliamentary Ofce of Science and Technology, 2004. Postnote: Speed

Cameras, number 218, http://www.parliament.uk/documents/upload/

POSTpn218.pdf.

Parsons, T., 2003. Why trafc cops play silly burglars. http://mirror.

co.uk/news/tonyparsons/tm column date=14072003-name index.html.

Pennay, D., 2005. Community attitudes to road safety: community attitudes

survey, wave 17, 2004. Report no. CR 214. Australian Transport Safety

Bureau, ACT, Australia.

Retting, R.A., Farmer, C.M., 2003. Evaluation of speed camera enforcement in

the district of Columbia. Transport. Res. Rec. 1830, 3437.

Retting, R., 2003. Speed cameraspublic perceptions in the US. Trafc Eng.

Contr. 44 (3), 100101.

Richter, E.D., Berman, T., Friedman, L., Ben-David, G., 2006. Speed, road

injury, and public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 27, 125152.

SARTRE, 2004. European drivers and road risk, Part 1: Report on principal

analyses, 4971, Arcueil, France, Institut National de Recherche sur les

Transports et leur Securite INRETS.

Slack, J., Massey, R., 2005. Soft Target motoristshalf of all court cases are

driving offences. Daily Mail, October 25, 2005.

Stradling, S.G., Campbell, M., Allen, I.A., Gorell, R.S.J., Hill, J.P., Win-

ter, M.G., Hope, S., 2003. The speeding driving: who, how and why?

Scottish Executive Social Research Development Department Research

Programme Research Findings 170/2003. http://www.scotland.gov.uk/

Publications/2003/08/17977/24935.

Transport 2000, 2003. Polls show public want speed cameras. Press release:

November 29, 2003. www.transport2000.org.uk.

You might also like

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Flores V Mallare-Phillips - Case DigestDocument2 pagesFlores V Mallare-Phillips - Case DigestRae DarNo ratings yet

- Joseph Stevens IndictmentDocument114 pagesJoseph Stevens IndictmentBrian WillinghamNo ratings yet

- 3 - Padlan v. DinglasanDocument6 pages3 - Padlan v. DinglasanMiguel ManzanoNo ratings yet

- Lawsuit Against Dr. Blickman/University of RochesterDocument11 pagesLawsuit Against Dr. Blickman/University of RochesterNews 8 WROCNo ratings yet

- The Soriano Petition (GR 191032) : de Castro vs. JBC, GR 191002, 17 March 2010Document11 pagesThe Soriano Petition (GR 191032) : de Castro vs. JBC, GR 191002, 17 March 2010Berne GuerreroNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-30912 April 30, 1980 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. AGAPITO DE LA CRUZ, Accused-AppellantDocument19 pagesG.R. No. L-30912 April 30, 1980 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. AGAPITO DE LA CRUZ, Accused-AppellantRache BaodNo ratings yet

- Travel AffidavitDocument5 pagesTravel AffidavitFreeman6790100% (1)

- Documento 3Document3 pagesDocumento 3Anonymous PlKbc7z5No ratings yet

- Ipc ProjectDocument13 pagesIpc Projectanon_909832531No ratings yet

- Standing Orders ActDocument27 pagesStanding Orders ActAkhil DevNo ratings yet

- Sample RRL From The InterwebzDocument12 pagesSample RRL From The InterwebzRachel AsuncionNo ratings yet

- Nagcarlan Pre Charge Security Inspection APECDocument12 pagesNagcarlan Pre Charge Security Inspection APECMark Alexander FenidNo ratings yet

- Raynor v. Wentz, 10th Cir. (2009)Document3 pagesRaynor v. Wentz, 10th Cir. (2009)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Daniel Franco, 1st Cir. (1993)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Daniel Franco, 1st Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- (U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictDocument6 pages(U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictFauquier NowNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics NotesDocument100 pagesLegal Ethics NotesEliza Rodriguez-BarengNo ratings yet

- Monsato v. Factoran Jr.Document2 pagesMonsato v. Factoran Jr.Alan Orquinaza100% (1)

- Gonzales v. CADocument2 pagesGonzales v. CAMaria AnalynNo ratings yet

- Anser Unit 1legal Right in A Wider SenseDocument6 pagesAnser Unit 1legal Right in A Wider SenseVideh Vaish100% (1)

- Abela v. Golez, 131 SCRA 12Document5 pagesAbela v. Golez, 131 SCRA 12Okin NawaNo ratings yet

- People V Vera DigestDocument3 pagesPeople V Vera DigestLuis Teodoro Pascua100% (1)

- Terri Grier Transcript 08192016Document5 pagesTerri Grier Transcript 08192016Nathaniel Livingston, Jr.No ratings yet

- CrimPro CompilationDocument95 pagesCrimPro CompilationArvin Jay Leal100% (2)

- 2 Memorandum of Law in Support of MotionDocument33 pages2 Memorandum of Law in Support of MotionLaw&CrimeNo ratings yet

- Federal Rules of Civil Procedure OutlineDocument25 pagesFederal Rules of Civil Procedure OutlinecodyNo ratings yet

- Appeal To High Court Under Code of Civil ProcedureDocument2 pagesAppeal To High Court Under Code of Civil ProcedureShelly SachdevNo ratings yet

- Sample of Affidavit of WitnessDocument1 pageSample of Affidavit of WitnessmjpjoreNo ratings yet

- Forensic Hair and FiberDocument2 pagesForensic Hair and FiberJohn Lloyd PalaparNo ratings yet

- Oriel Magno v. CADocument2 pagesOriel Magno v. CAKaren Joy MasapolNo ratings yet

- Some Brief Thoughts (Mostly Negative) About Bad Samaritan Laws PDFDocument21 pagesSome Brief Thoughts (Mostly Negative) About Bad Samaritan Laws PDFWilliam KennedyNo ratings yet