Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Against Ditransitivity

Uploaded by

torreasturOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Against Ditransitivity

Uploaded by

torreasturCopyright:

Available Formats

Against ditransitivity

1

MARA CRISTINA CUERVO

Probus 22 (2010), 151180 09214771/10/022-0151

DOI 10.1515/prbs.2010.006 Walter de Gruyter

Abstract

The notion of ditransitivity is explored at the lexical, syntactic and surface

levels. By focusing on several types of ditransitive sentences in Spanish it is

revealed that there is a triple dissociation between these levels. First, it is

shown that the availability of a ditransitive structure (syntactic level) for a

certain verb does not depend on the verb being ditransitive (lexical level). Sec-

ond, causative structures with dative arguments are shown to be ditransitive

at the surface level, but not to have an underlying ditransitive structure. Fi-

nally, cases of unaccusative sentences with dative arguments are analysed as

instances of ditransitive structures without lexical or surface ditransitivity. The

paper argues that ditransitivity is at best a pre-theoretical, descriptive notion,

and that ditransitive verbs in fact belong to Levins (1999) non-core transitives:

ditransitives are just transitives compatible with taking a relation between two

individuals as complement. This analysis accounts for the intralinguistic and

crosslinguistic variation in the expression of the relation, both in terms of type

(two DPs related by a transitive preposition or an applicative head) and num-

ber of objects realized or omitted. Although the idea that there is no syntactic

ditransitivity that is, that no single verbal head can take two complements

has been implicit in most generative work of the last two decades, it has not

been directly explored. This investigation leads to the conclusion that a syntac-

tic property, binary branching, is at the basis of the impossibility of syntactic

and lexical ditransitivity. Thus, this result suggests that syntax restricts not only

possible structures but possible lexical meanings as well.

1. I would like to thank Violeta Demonte, Mara Luisa Zubizarreta and two anonymous Probus

reviewers for invaluable comments and suggestions. Funding for this research was provided

in part by a Connaught Grant from the University of Toronto.

152 Mara Cristina Cuervo

Ce pluriel est bien singulier.

J. L. Borges,

Las alarmas del doctor Amrico Castro.

1. Introduction

Ditransitives have been at the centre of research on argument structure and syn-

tactic theory. The very idea of a verb taking two internal arguments has given

rise to a series of challenges to linguists. Ditransitives have been a challenge

for theories of argument structure, theories which focus on the relation be-

tween lexical semantics and syntactic structure, and attempt to account for the

observed regularities in the relation between semantic role and syntactic posi-

tion. Minimally, ditransitives pose a challenge because intralinguistically they

participate in argument structure alternations (such as the dative and locative

alternations), and crosslinguistically, they exhibit interesting variation in terms

of the morphosyntactic expression of the arguments (such as case and word or-

der). Ditransitives have also been a problematic case for syntactic theory itself.

The initial idea that two selected semantic arguments of a verb are expressed

as two sisters to the verb has been challenged by data concerning asymmet-

ric hierarchical relations. These data have served as empirical evidence against

ternary branching, leaving binary branching as the only option. For theories

that only allow for binary branching be it a constraint on representations or

a consequence of the nature of syntactic operations however, the task of ac-

counting for the semantic selection of two arguments and the correct syntactic

relations between the arguments and the verb has not been straightforward.

The notion of ditransitivity itself seems fuzzy sometimes. There exists a ten-

sion between the notion of ditransitivity as a lexical property of verbs, as a

type of syntactic structure or a type of sentence with two argument DPs other

than the subject. Depending on which notion one is dealing with, the cases

that fall under the name of ditransitive change dramatically. As a lexical se-

mantic notion delimiting a class of verbs (which I will call lexical ditransi-

tivity), ditransitives are opposed to intransitives as well as to monotransitives,

covering verbs like give, send, tell but excluding dance, arrive, eat, cook and

break. Within this notion, there is no denite consensus on whether verbs like

put, extract and load, which usually take a DP and a PP, are equally ditransi-

tive. If, on the other hand, being ditransitive is a property of syntactic structure

(deep ditransitivity), the notion can cover any kind of structure where there

are two internal arguments of the verb, irrespective of whether there is an exter-

nal argument and, under Burzios generalization, accusative case. This type of

ditransitivity without transitivity is assumed by many for unaccusative dative

experiencer constructions in Italian and Spanish (as argued for by Belletti &

Against ditransitivity 153

Rizzi 1988). Finally, if ditransitive is dened as a type of sentence, the notion

crucially takes into account the morphosyntactic shape of the arguments (their

coding properties, in the sense of Levin 1999) and, in languages with a three

case systemsuch as Italian, Spanish, German, and Japanese, the notion involves

two DPs, one in accusative and one in dative case (surface ditransitivity).

In this work, I present a detailed study of the notion(s) of ditransitivity

through the analysis of ditransitives in Spanish. Spanish is a language in which

a dative argument can be added to practically any type of verb, therefore

exhibiting an immense array of cases which can be considered ditransitive un-

der at least one of the interpretations mentioned above. Although data comes

mainly from Spanish and English, I believe the conclusions generalize across

languages. The analysis leads to the conclusion that there is no real notion

of ditransitivity, that there are no verbs which license two internal arguments.

In other words, ditransitivity is not a theoretically meaningful notion either in

its lexico-semantic or in its syntactic versions. Although the idea that there is

no syntactic ditransitivity has been implied one way or another by most work

on ditransitives within generative approaches at least since Bakers (1988) in-

corporation and Larsons (1988) Single Complement Hypothesis, most work

continue to treat ditransitives as a well dened syntactic or semantic class.

This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, I present two main types

of analyses a derivational approach and a constructionist approach that

have been applied to the study of ditransitives in their three dimensions: lexi-

cal, syntactic (deep ditransitivity) and morphosyntactic (surface ditransitivity).

Through the analysis of double-object constructions in Spanish I show that

surface ditransitivity and deep ditransitivity equally apply to verbs that nobody

would consider lexically ditransitive. Section 3 deals with the structure of di-

transitive sentences with causative verbs. These data constitute a case of surface

ditransitivity which does not correspond either to lexical or to deep ditransitiv-

ity. Section 4 deals with one type of two-argument unaccusative structures,

analysed as double-objects, that is, cases of deep ditransitivity without lexi-

cal or surface (di)transitivity. In Section 5 I reconsider all the data and show

that there is a triple dissociation between the different notions of ditransitivity.

I argue that, in fact, the only notion of ditransitive we can keep is a surface,

pre-theoretical notion, which informally distinguishes a group of predicates,

within the general class of (non-causative) transitives, which tend to appear

with two arguments. Section 6 presents the general implications of this study

for a syntactic theory that determines argument structure and radically restricts

the relation between the lexicon and syntactic structure.

154 Mara Cristina Cuervo

2. Ditransitives and double-objects

The traditional denition of a ditransitive verb is a verb that takes or selects

three arguments, or two internal (i.e., non-subject) arguments. This selection

can be emphasized as a semantic or a syntactic selection. Within a view of

argument structure as the consequence of the lexical semantics of a verb (the

projectionist view), the verb selects two specic -roles which are then asso-

ciated with two types of phrases (typically, DP-DP or DP-PP); these, in turn,

are mapped into certain syntactic positions. Only a verb that requires two inter-

nal arguments is considered ditransitive, thus opposing monotransitives such as

eat, cook and admire to ditransitive tell, show, send. The syntactic expression

of a verb selecting two internal -roles turned problematic as soon as it was

observed that the relation of the two DPs with the verb wasnt the same, and

that there were hierarchical asymmetries between the objects (Chomsky 1981;

Barss & Lasnik 1986; Pesetsky 1995).

(1) a. Sara sent a bracelet to Maria.

b. Sara sent Maria a bracelet.

Larson (1988) proposed that the English double-object construction, as in (1b),

was derived from the prepositional counterpart (1a) by a passive-like move-

ment. Leaving details aside, the crucial aspect of his approach is that there are

two layers of VP, two parts of the verb, and each of the internal arguments is

related to the V head of a different layer. The preposition to is absorbed and

merges with the verb. This operation is similar to Bakers (1988) incorporation

as the source of applicative (double-object) constructions.

(2) a. Prepositional

VP

Spec V

V

send

i

VP

DP

a letter

V

V

t

i

PP

to Mary

Against ditransitivity 155

b. Double object (Larson 1988)

VP

Spec V

V

send

i

VP

DP

Mary

j

V

DP

a letter

V

t

i

DP

t

j

These derivational approaches, although inspiring and productive, raise several

problems. Among the most serious, they cannot capture the differences in the

interpretation of the arguments in the variants or the related restrictions on the

alternation (see Cuervo 2003; Demonte 1995; Krifka 2004; Oehrle 1976; etc.

for discussion). Moreover, it is difcult to understand what the trigger of the

syntactic operation is, as well as accounting for the optionality, obligatoriness

or impossibility of its application in the different cases.

There have also been non-derivational analyses of double-objects, which can

more naturally account for the observed interpretative contrasts between vari-

ants while maintaining the account of structural properties (denDikken 1995;

Harley 2002; Marantz 1993; Pesetsky 1995; Pylkknen 2008, among many

others). With the exception of Marantzs 1993 verbal applicative analysis, in

all these approaches the verb takes one complement either a PP, an Applica-

tive phrase, or a small clause within which the two internal arguments are

licensed.

2.1. Ditransitives as double-objects

In Spanish ditransitive sentences, the two internal arguments typically appear

postverbally in the order accusative >dative.

2

The dative argument is preceded

by a, which I take to be a case marker rather than a full preposition projecting a

2. The order dative-accusative is in most cases also possible, but it is a marked order, usually

accompanied by special intonation. Of course, either argument can appear sentence-initially

as topic or focus.

156 Mara Cristina Cuervo

PP (Demonte 1995; Kempchinsky 1992; Strozer 1976; among others). A dative

clitic, hosted by the verb, matches the person and number features of the dative

DP, irrespective of whether the dative argument is overt or null.

3

(3) a. Pablo

Pablo

le

cl.dat

mand

sent

una

a

postal

postcard

a Vicky.

Vicky.dat

Pablo sent Vicky a postcard.

b. Pablo

Pablo

nos

cl.dat.1P

dijo

told

la

the

verdad

truth

(a nosotros).

us.dat

Pablo told us the truth.

Although it had been previously assumed that there was no dative alternation

in Spanish (or other Romance languages, Kayne 1975), several authors in the

generative framework have argued that Spanish clitic-doubled ditransitive con-

structions have the crucial syntactic and semantic properties of the double-

object construction (Bleam 2003; Cuervo 2003; Demonte 1995; Zhang 1998).

In fact, this idea was more or less explicit 20 years before in Strozer 1976,

who argues for a correlation between clitic doubling and type of indirect ob-

ject. She claims that there are two kinds of indirect objects (dative arguments),

which she labels IND

1

and IND

2

. IND

1

are ordinary goals and can only

appear with verbs of transfer, e.g., give, sell, lend. IND

2

would be involved

goals, which can have different meanings in different verbal contexts.

Demonte (1995) builds on Larsons (1988) proposal to claimthere are double-

objects in Spanish which, beyond some morphosyntactic differences with En-

glish, exhibit many of the central properties of English double-objects. There

have also been non-derivational approaches to Spanish double-objects. De-

monte (1994) argues for a lexical approach to the dative alternation, each vari-

ant the consequence of a different lexico-conceptual structure associated with

the verb. Bleam (2003) takes Harleys have-clause approach, while Cuervo

(2003) builds on Pylkknens (2000, 2008) applicative analysis.

(4) Andrea

Andrea

le

Cl.DAT

envi

sent

un

a

diccionario

dictionary.ACC

a Gabi.

Gabi.DAT

Andrea sent Gabi a dictionary.

3. In the lasta dialect of Madrid, dative clitics also mark gender, specically, a third person

dative associated with an animate feminine dative appears as la (accusative feminine in most

other dialects).

Against ditransitivity 157

(5) TP

T

Andrea

v

Root

envi

ApplP

DP

Dat

a Gabi

Appl

le

DP

Acc

un diccionario

(Cuervo 2003)

In the structure above, the dative argument is licensed as the specier of an ap-

plicative head, the accusative object is licensed as the complement. In turn,

the applicative phrase combines as the complement of the verb. This posi-

tion below the verb (the verbal root) determines that ditransitives are a case

of Pylkknens low-applicative (as opposed to high applicatives which merge

above the verb). The low applicative expresses a dynamic possessive relation

between two individuals, the two internal arguments of ditransitive verbs. Ac-

cording to Pylkknen, the interpretation of so-called goals and benefactives

in double-object constructions can be generalized in the notion of recipient;

this interpretation arises as the meaning of one sub-type of low applicative

head, Appl-to.

(6) Pylkknens Low-APPL-TO (Recipient applicative):

4

x.y.f

es,t

.e. f(e,x) & theme (e,x) & to-the-possession(x,y)

In the case of verbs such as mandar, decir and enviar in (3)(4), all the levels

of ditransitivity coincide: the two non-agentive arguments of the verb, theme

and recipient (lexico-semantic ditransitivity) are expressed as two internal DPs

(deep, syntactic ditransitivity), which appear postverbally, one in accusative,

one in dative case (cf. Table 1).

4. The denotation of a low applicative head represented in (6) states that rst the head takes the

DP theme as an argument, then it relates that DP to the applied argument and nally relates

those arguments to the event (by taking the verb as its third argument).

158 Mara Cristina Cuervo

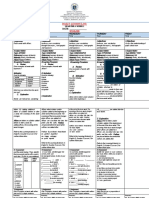

Table 1. Levels of ditransitivity for lexical ditransitives

Level

Lexical Deep Surface

Ditransitive verbs

2.2. Double-objects for monotransitives

Double-objects in Spanish alternate not only with prepositional variants with

goal meanings, but also with benefactive para, and locative en.

(7) a. Pablo

Pablo

compr

bought

un

a

libro

book

para

for

Tesi.

Tesi

Pablo bought a book for Tesi.

b. Pablo

Pablo

le

cl.dat

compr

bought

un

a

libro

book

a Tesi.

Tesi.dat

Pablo bought Tesi a book.

(8) a. Pablo

Pablo

puso

put

limn

lemon

en

in

el

the

t.

tea

Pablo put lemon in the tea.

b. Pablo

Pablo

le

cl.dat

puso

put

limn

lemon

al

the

t.

tea.dat

Pablo put lemon in the tea.

These cases, already analyzed in Masullo (1992), Demonte (1995) and Cuervo

(2003), can nevertheless be captured by the same applicative structure assumed

for lexical ditransitives. The interpretation of the dative DP variants of the

benefactive and locative PPs a Tesi (7) and al t (8) can be subsumed under

the notion of recipient or Strozers involved goals. In order for the involved

goal dative to be available for an inanimate dative DP, the entity to which the

direct object refers must become an integral part of the entity mentioned by the

dative, (9). In other words, the possessive relation must be inalienable.

5

This

restriction does not apply to animate datives.

(9) Pablo

Pablo

le

cl.dat

puso

put

limn

lemon

al

the

t

tea.dat

/

/

*a la

the

heladera.

fridge.dat

Pablo put lemon in the tea / in the fridge.

5. In many languages, DOCs are restricted to animate recipients; Spanish seems to be special in

this respect. The extent and motivations of this phenomenon, however, go beyond the scope

of this paper.

Against ditransitivity 159

There are many cases of the double-object construction in which the dative

DP is interpreted as the source rather than the recipient of the direct object.

Pylkknen accounts for this reversed direction in the transfer of possession

relation in terms of a different sub-type of low applicative, Appl-from.

(10) Low-APPL-FROM (Source applicative):

x.y.f

es,t

.e. f(e,x) & theme (e,x) & from-the-possession(x,y)

As Cuervo (2003) notes, this type of lowapplicative also exists in Spanish, with

all the same morphological and syntactic properties of recipient constructions.

The restrictions on inalienable possession also apply to source double-objects.

(11) Pablo

Pablo

le

cl.dat

sac

took-out

los

the

botones

buttons

a la

the

camisa

shirt.dat

/

/

*al

the

cajn.

drawer.dat

Pablo took the buttons out of the shirt/drawer.

Another important group of dative arguments in ditransitive sentences are the

DPs interpreted as the possessors of the entity expressed as the direct object

DP.

(12) Le

cl.dat

extirparon

they-took-out

el

the

diente

tooth

a Juan.

Juan.dat

They took out Juans tooth. (Demonte 1995: Ex. (43b))

Many authors have considered these structures as derived ditransitives, the

result of the raising of a possessive DP fromwithin the direct object DP. This is

the analysis of possessor datives in Hebrew or Spanish of Borer & Grodzinsky

1986, Demonte 1995, Landau 1999, and Masullo 1992 (see Jeong 2007 for a

generalized approach to low applicatives based on movement). The basis of

this idea is the assumption that the dative DP is not an argument of the verb

(i.e., it is not licensed by a ditransitive verb) but is licensed by the noun head

of the direct object. In contrast to these derivational approaches, Kempchinsky

(1992) and Cuervo (2003) propose that the dative possessor is generated in the

same position as datives with prototypical ditransitive verbs (see Cuervo 2003

for explicit arguments in favour of a non-derivational analysis of possessor

datives). In her analysis of Hebrew possessor datives, Pylkknen (2008) also

argues against a raising analysis of possessors and claims these are cases of

source applicatives.

In examples like (12) the dative DP can be understood as the possessive

source, given that extirpar take-out is a transfer predicate. There exist, how-

ever, many other cases in which there is no dynamic relation between the two

160 Mara Cristina Cuervo

arguments, making the source analysis less convincing.

6

This is the case with

verbs which, although dynamic, do not express transfer (besar kiss, lavar

wash) and with stative verbs (admirar admire, envidiar envy). Dative pos-

sessors are interpreted somewhat differently from genitive possessors within

DPs. I think Strozers concept of involvement best describes the difference:

dative possessors are involved possessors, possessors which act as participants

in the event described by the verb. They are not necessarily affected ((13b)

does not express or imply that Tesi is affected, as is also the case in the mono-

transitive Pablo admira a Tesi, Pablo admires Tesi) nor is the structure some

type of resultative with different aspectual properties in comparison with the

genitive variant or a recipient dative. If in some case the dative is interpreted as

affected, it is because it is the possessor of an affected direct object, as might

be the interpretation of (14).

(13) a. Pablo

Pablo

le

cl.dat

bes

kissed

la

the

mano

hand

a la

the

reina.

queen.dat

Pablo kissed the queens hand.

b. Pablo

Pablo

le

cl.dat

admira

admires

los

the

guantes

gloves

a Tesi.

Tesi.dat

Pablo admires Tesis gloves.

(14) Pablo

Pablo

le

cl.dat

aplast

crushed

la

the

mano

hand

a la

the

reina.

queen.dat

Pablo crushed the queens hand.

In order to cover these cases under the low applicative analysis, the idea that

low applicatives only express dynamic relations of possessive transfer must be

dropped. Cuervo (2003) proposes that there is a third type of low applicative,

which expresses a static possessive relation between two individuals: Appl-at.

(15) Low-APPL-AT (Possessor applicative):

x.y.f

es,t

.e. f(e,x) & theme (e,x) & at-the-possession(x,y)

Sentences in which the two arguments are animate highlight the important con-

trast in meaning between the genitive and the dative, low applicative variants.

(16) Pablo

Pablo

le

cl.dat

envidia

envies

la

the

hija

daughter.acc

a Valeria.

Valeria.dat

Pablo envies Valeria the daughter.

(17) Pablo

Pablo

envidia

envies

a la

[the

hija

daughter

de

of

Valeria.

Valeria].acc

Pablo envies Valerias daughter.

6. This is the case not only in Spanish but also in Hebrew and in just a few cases in English.

Against ditransitivity 161

The alternation represented by the sentences in (16)(17) is similar to that of

the sentences in (13) and their respective genitive variants. Sentences (16) and

(17), however, are clearly not paraphrases.

7

In (17), Pablo envies a woman,

who is identied as Valerias daughter. In (16), Pablo does not so much envy

a person as a situation or relationship (having a daughter, or having a daughter

as Valerias). In both congurations Valeria is related to the theme object. The

crucial difference is in the relation between Valeria and the event expressed by

the verb. In the genitive construction, Valeria is licensed as part of the theme

object and it is not related with the verb at all. In the dative construction, in

contrast, Valeria is licensed by Appl as an event argument and, after combining

with the theme object, relates to the verb as its complement. The semantics of

the double-object variant highlights, again, that there is a direct relationship

between the two objects, and that the whole constituent combines with the verb

(the two DPs have referential properties and are still interpreted as separate

participants in the event).

8

The structure of low applicatives allows us to express exactly that: the Ap-

plicative Phrase expresses a relation between two individuals that is embedded

under the verb. In the semantic interpretation of the Low-Applicative-at, there

are two variables for individuals that relate to the event: the theme and the pos-

sessor; in the interpretation of the genitive construction there would be only

one for the theme DP. The relevant structures of sentences (16) and (17) are

represented in (18) and (19), respectively.

7. The same contrast arises between the sentences below in British English and others who

accept (ib).

(i) a. Stephanie envies Daniels father.

b. Stephanie envies Daniel his father.

8. Pylkknens proposal for the semantic composition of low Appl depends, at least in part, on

her assumption of a fully neo-Davidsonian approach to object arguments (which are licensed

by a separate predicate Theme, as in Parsons 1990). If one abandons this position in favour of

a partial neo-Davidsonian approach (as proposed in Kratzer 1996), it is possible to view the

composition of the root with ApplP in the same terms a root combines with a transitive PP, as

in hide the books in the drawer. The formalization of this idea however, is outside the scope

of this paper.

162 Mara Cristina Cuervo

(18) Possessor dative construction

vP

v

Root

envid-

ApplP

DP

a Valeria

Appl

le

DP

la hija

(19) Genitive construction

9

vP

v

Root

envid-

DP

D

la

NP

hija

de Valeria

Notice that in order to spell out the difference in meaning between the dative

construction and the genitive construction, it was not necessary to make ref-

erence to the notion of affectedness, inalienability or transfer of possession.

In fact, none of these notions are relevant here. There is no sense in (16) that

Valeria is affected at all. Finally, we have seen that there is no sense in which

Valeria gets or loses anything.

9. That the de-PP is embedded under the DP, and not related to it as a PP relates to the DP theme

in prepositional ditransitives, is supported by the following contrast concerning pronominal-

ization.

(i) a. Pablo

Pablo

envidia

envies

[a la

the

hija

daughter

de

of

Valeria].

Valeria

*

Pablo

Pablo

la

envies

envidia

her

de

of

Valeria.

Valeria

b. Pablo

Pablo

sac

took

[la

the

pastilla]

pill

[de

of

la

the

caja].

box

Pablo

Pablo

la

took

sac

it

de

from

la

the

caja.

box

Against ditransitivity 163

Table 2. Levels of ditransitivity for non-lexical ditransitives

Level

Lexical Deep Surface

Benefactives NO

Sources NO

Possessors NO

Again, the morphosyntactic properties of the sentences in (13) are identi-

cal to the properties of prototypical double-objects in terms of case, word or-

der, clitic doubling, and the structural properties which depend on asymmet-

ric c-command (e.g., anaphor and possessive binding, weak cross-over, scope,

[Bleam2003; Cuervo 2003; Demonte 1995]). When we consider the properties

of the three sub-types of Spanish low applicatives, what emerges is a general-

ization at the syntactic (deep) and morphosyntactic (surface) levels of ditransi-

tivity which does not correspond to the lexico-semantic level, as is illustrated

in Table 2.

Irrespective of the particular analysis adopted (incorporation, passive-like

movement, possessor raising, low applicatives, base-generated Larsonian VP

shells), once we have a double-object construction, there is no way to distin-

guish structurally between ditransitive and non-ditransitive verbs. In ditransi-

tive sentences with ditransitive enviar send and poner put and monotran-

sitive comprar buy, admirar admire or besar kiss, the syntactic relation

between the two individuals and their relation with the verb is the same be the

dative DP selected by the verb or not.

10

In other words, there is no struc-

tural or morphosyntactic notion of adjunct (non-argumental or extra argument)

dative indirect object as opposed to an argumental dative object.

11

In sum, neither the interpretation of the arguments, nor the syntactic or mor-

phosyntactic properties of double-objects depend on whether the verb is lexi-

cally ditransitive or not.

12

Spanish double-objects show that there exists a dis-

sociation between lexico-semantic ditransitivity, and structural and surface di-

transitivity.

10. But see Demonte 1994 for a discussion of a contrast between possibility of passivization along

the lines of Strozers distinction between IND

1

and IND

2

.

11. One could make a distinction in terms of the possibility of omitting the dative: always possible

to omit the dative with monotransitives, not possible to omit it if the verb is ditransitive. For

discussion of omission, see Section 5.

12. Several of Demontes 1994, 1995 and Cuervos 2003 examples of Spanish double objects

that illustrate asymmetric c-command, scope and interpretative contrasts do not correspond

to lexical ditransitives, such as the equivalents of steal, buy, cook, wash, etc.

164 Mara Cristina Cuervo

3. Ditransitive sentences without ditransitive structure

The previous section presented the case of prototypical ditransitives in which

the three levels of ditransitivity can coincide. It also showed that in most other

cases of double-objects, deep and surface ditransitivity does not correlate with

lexical ditransitivity. In this section I present an analysis of another class of

ditransitive sentences, those with a causative verb. It will be shown that they

exhibit another kind of dissociation: Causatives with dative arguments are sur-

face ditransitives without lexical or deep ditransitivity.

13

In Spanish, causative verbs (i.e., synthetic causatives which participate in

the causative alternation) such as burn, break, melt, open, can appear with an

added dative argument (20). The morphosyntactic shape of these sentences is

that of double-objects, as seen in the previous section: The normal, wide focus

interpretation word order is postverbal Acc > Dat; the dative DP is preceded

by a and must be clitic-doubled; in terms of hierarchical relations, the dative

DP is higher than the accusative DP (see Demonte 1995 and Cuervo 2003).

(20) a. Madariaga

Madariaga

le

cl.dat

rompi

broke

la

the

impresora

printer

a Ana.

Ana.dat

Madariaga broke the printer on Ana.

b. Madariaga

Madariaga

me

cl.dat.1s

cambi

changed

todas

all

las

the

reglas.

rules

Madariaga changed all the rules on me.

In spite of morphosyntactic appearances, two issues compel me to suspect that

the structure of datives with causatives is not a double-object construction, i.e.,

not a low applicative. One reason is semantic, the other structural.

First, the interpretation of the dative DP does not correspond to any of the

three subtypes of low applicatives. Although examples similar to (20a) have

been presented as cases of possessor raising (Landau 1999), source applicatives

(Pylkknen 2000) or possessor applicatives (Cuervo 2003), the interpretation

is not necessarily that of a possessor of the direct object but of an individual

affected by the change of state of the object. In (20b), for instance, it cannot

be said that the speaker (corresponding to dative me) is the recipient (Appl-

to), or possessor of the rules (Appl-at), nor that she looses the rules (Appl-

from). The interpretation is, rather, that the speaker now has different rules:

the dative argument is presented as related to the new state of the object. Under

the assumption that this difference in interpretation with respect to double-

13. As an anonymous reviewer points out, analytical causatives with hacer make are another

(potential) case of surface ditransitivity without lexical or syntactic ditransitivity. I will nev-

ertheless concentrate here only on so-called lexical causatives without hacer.

Against ditransitivity 165

objects arises from compositional semantics, we are forced to conclude that

the underlying structure of ditransitive causatives must be different.

The second problem for a low-applicative analysis of causatives is struc-

tural. Low applicatives are dened semantically and syntactically as a relation

between two individuals, two DPs. The applied argument is licensed as a spec-

ier of the Appl head and relates to the DP the head takes as its complement.

On the other hand, many authors have proposed that the object of causatives is

licensed as a specier of the verb, which lexicalizes the resulting state (Hale &

Keyser 1993, 2002; Levin 1999; Levin & Rappaport 1995; Nash 2002; Harley

2006; Zubizarreta & Oh 2007; among others).

(21) V

1

V

1[CAUSE]

V

2

DP V

2

the pot V

2

Root

break

(H&K 2002: 3)

Going over the justication of this structure is beyond the scope of this work;

here I assume it is correct in that objects of causatives are licensed as inter-

nal speciers.

14

As a result, the causative structure, in which the object DP

is merged above the verb, is incompatible with low applicatives, dened as a

relation of two DPs below the verb.

(22) v

1

v

1

vP

2

Appl DP v

2

v

2

Root

*

The semantics of the sentence and the syntax of causatives both indicate that

the dative DP is applied not to the direct object but to the state of which the

direct object is the subject. This structure is represented in (23).

14. See Cuervo 2008 for evidence of the internal specier position of the objects of causatives in

terms of restrictions on bare nouns.

166 Mara Cristina Cuervo

(23) VoiceP

DP

Subj

vP

do

Voice ApplP

v

DO

/ 0

Appl

DP

Dat

Appl vP

BE

DP

Acc

v

BE

Root

The structure of causatives is complex, consisting of two subevents, each ex-

pressed by a verbal layer (vP). This contrasts with the simple, mono-eventive

structure of mono-transitives and the ditransitives seen in Section 2. The ap-

plicative is merged between the two subevents: it is the object of the higher,

dynamic event, and it takes the lower, stative vP as its complement. The ap-

plied dative DP participates in both subevents: this is the structural position

which denes affectedness as a congurational meaning (Alsina 1992, Marantz

1993). Affectedness is the common interpretation for datives with causatives

as those in (20). The possessive interpretation mentioned in previous analyses

may be part of the interpretation of these affected datives, but only as an in-

ference.

15

We might infer the dative DP is the possessor of the object DP as

the reason why the individual is presented as affected by the new state of the

object. Cases as (20b) show that possession of the object is not entailed. These

affected applicatives must be distinguished from low applicatives, then, both

semantically and syntactically. The two kinds of applicatives have a common

possessive nature, but the object of the possession is different: an entity in low

applicatives, a state in affected applicatives. The semantic difference might not

arise as a difference in the meaning of the applicative head per se, but as a

consequence of the different type of complement the applicative takes. In turn,

the fact that the applicative in (23) is embedded under another vP distinguishes

15. In Section 2.2, the opposite was shown to apply to double-objects: a possessive relation was

entailed while affectedness could be an inference or not.

Against ditransitivity 167

affected applicatives from Pylkknens high applicatives (dened as selecting

a VP under Voice).

16

To sum up, we have seen that there exists a type of sentence in Spanish with

all the surface morphosyntactic properties of ditransitives. These sentences,

however, do not correspond to the projection of verbs selecting two theta roles

or two arguments; rather, they are the expression of causative verbs with a

complex event structure, expressed as two vP layers in the syntax. Again, we

have morphosyntactic (surface) ditransitivity without lexical ditransitivity. In

the case of these affected applicatives, the dissociation is even deeper: these

ditransitive sentences do not even have a ditransitive structure in which there

are two DP arguments internal to the same vP, that is, they are not ditransitives

in the syntactic, deep sense.

4. Ditransitive unaccusatives

We have seen two cases of dissociation in the notion of ditransitivity: deep

and surface ditransitives without lexical ditransitivity, and surface ditransitives

without lexical or deep ditransitivity. We havent seen any case of ditransitiv-

ity at some level without surface ditransitivity. Is it possible to have such a

case? What would a ditransitive structure look like without the morphosyn-

tax of ditransitives? If deep ditransitivity involves two internal arguments, we

must look for this structure merged under a conguration without accusative

case (under the generalized view that dative case in Spanish is inherent case).

There are indeed many sentences in Spanish in which we nd two arguments,

one in nominative which triggers verb agreement and another dative DP,

and no possibility of an accusative DP.

(24) a. Pablo

Pablo

le

cl.dat

habl

talked

a la

the

reina.

queen.dat

Pablo talked to the queen.

b. A Pablo

Pablo

le

cl.dat

gustan

like.3p

los

[the

guantes

gloves

de

of

Tesi.

Tesi].nom

Pablo likes Tesis gloves.

c. A Pablo

Pablo

le

cl.dat

llegaron

arrived.3p

los

the

libros.

books.nom

The books arrived to Pablo. Pablo got the books.

16. As an anonymous reviewer points out, Pylkknens denition of high applicatives is based on

their complement being a VP. Although Pylkknen does not state that they merge immediately

under Voice, all her examples are of this nature. The fact that the (affected) interpretation of

the applied argument requires the consideration not only of the complement of Appl, but also

of the structure immediately above it seems to point towards a distinction.

168 Mara Cristina Cuervo

d. A Pablo

Pablo

se

se

le

cl.dat

quemaron

burnt.3p

los

[the

guantes

gloves

de

of

Tesi.

Tesi].nom

Tesis gloves got burnt on Pablo.

The rst sentence is arguably not a case of deep ditransitivity but a unergative

activity verb hablar with an external argument and an indirect object. There are

a few verbs in Spanish which can appear in this conguration, such as sonreir

smile, golpear hit, agradecer thank, gritar shout. In most cases the root

seems to lexicalize a direct object (sonreir as hacer una sonrisa make a smile,

golpear as dar un golpe give a blow).

The other three sentences are formed with different types of unaccusative

predicates: (24b) contains a psych predicate; (24c) contains a simple unac-

cusative, a process unaccusative in Masullos (1992) terminology; (24d) incor-

porates a dative DP to an inchoative the se intransitive variant of causative

verbs. Since these three sentences are arguably unaccusative, they are poten-

tial examples of deep ditransitivity without surface transitivity. This would be

the case if the two arguments are generated as internal arguments and one be-

comes a surface subject, as generally assumed. This double-object analysis has

been proposed by Belletti & Rizzi for Italian, and was followed by Masullo

(1992) and Bruhn de Garavito (2002) for Spanish psych predicates. Fernndez

Soriano (1999) and Cuervo (to appear), however, have questioned this analysis

and argued that the dative DP is not an internal argument and, therefore, psych

predicates do not have a double-object structure. The double-object structure

of inchoatives has also been called into question given facts of restrictions on

bare nouns for the postverbal nominative, and the apparent predicational rela-

tion between verb and nominative DP (Cuervo 2008).

In order to avoid confusion and controversy, then, I will focus on the struc-

tures of the poster case of Spanish unaccusatives: simple (se-less) verbs of

change or existentials, such as llegar arrive, salir go out, crecer grow,

faltar lack, sobrar be extra, quedar remain. Is this a case of deep ditran-

sitivity? Are datives in these constructions low applicatives in terms of their

semantics and their syntax? Lets start with their semantics. It seems that in-

deed, we nd cases in which the dative DP is interpreted as each one of the

three attested sub-types of low applicatives in ditransitive constructions.

(25) a. (Recipient) A Gabi

Gabi.dat

le

cl.dat

llegaron

arrived.pl

buenas

good

noticias.

news

Gabi got good news.

b. (Source) A Gabi

Gabi.dat

le

cl.dat

salieron

came-out.pl

tres

three

canas.

white hairs

Gabi got three white hairs.

Against ditransitivity 169

c. (Possessor) Al

the

ensayo

essay.dat

le

cl.dat

sobran

are-extra.pl

hojas.

pages

The essay has too many pages.

The possessive reading (either dynamic or static) is found in all the unac-

cusative sentences as those in (25). As in the case of double-objects with tran-

sitive predicates, the construction is available both for animate and inanimate

dative DPs, with inanimates being restricted to inalienable possession (part-

whole) relations.

(26) Al

the

rbol

tree.dat

/

/

*Al

the

patio

patio.dat

le

cl.dat

faltan

lack.pl

hojas.

leaves

The tree/the patio is missing some leaves.

In order to obtain this interpretation, the simple unaccusative structure is aug-

mented by the addition of an applied argument. Structure (27b) expresses the

right hierarchical relations and accounts for the semantics of the construction

in terms of a possessive relation between two individuals under a predicate of

change or existential (Cf. Fernndez Soriano 1999). As in other unaccusative

constructions in Spanish, the dative DP moves to preverbal position (the sen-

tence is about the dative DP) while the lower object receives structural case

in situ and triggers verbal agreement.

(27) a. Simple unaccusatives

vP

v

/ 0

Root DP

lleg- buenas noticias

b. Double-object unaccusatives (=(25a))

vP

v

/ 0

Root

lleg-

ApplP

DP

a Gabi

Appl

le

DP

buenas noticias

170 Mara Cristina Cuervo

Simple unaccusatives as those above present another kind of dissociation

among levels of ditransitivity. In this case, there is no lexical ditransitivity

(these predicates are never included in lists of ditransitives) nor morphosyn-

tactic, surface ditransitivity (there is no accusative, the normal word order is

Dat > Nom). The underlying structure is, however, that of a double-object, the

only difference being that the verb and its complement applicative phrase are

not embedded under a transitive v or Voice but under an unaccusative v which

does not license an external argument.

17

Although there is no lexical ditransitivity, there is semantic ditransitivity in

some sense. Unaccusative double-objects have the semantics of low applica-

tives, which arise from the meaning of the applicative head and compositional

semantics. If we dene at least some sense of ditransitivity as a (possessive or

locative) relation between two individuals below the verb (a possible rephras-

ing of two internal theta roles), these cases are ditransitive also semantically.

I address this issue in the next sections, when the dissociations are discussed

and an explanation is searched for.

5. Ditransitivity deconstructed

We started this work distinguishing three levels of ditransitivity, three levels

at which we should look for ditransitive properties: lexical, syntactic and mor-

phosyntactic. The lexical level corresponds to the semantic denition of di-

transitive verbs as verbs that select two theta roles and license two internal

arguments. The syntactic or deep level corresponds to the structure of a verb

with two VP-internal arguments (that is, two arguments internal to the same

vP, VP or RootP). Finally, the morphosyntactic properties of ditransitivity are

more language specic and correspond to the coding properties of the language

(case, word order, etc.), which determine the surface shape of sentences. As ex-

pected, in sentences with verbs considered ditransitive, the three levels coincide

and provide the prototypical case of ditransitivity. Spanish has shown, how-

ever, that prototypical cases are few and that ditransitivity can be distributed

unevenly across the three levels as illustrated in Table 3.

17. I assume here that what takes the ApplP as complement is a root, which becomes a verb

of a certain kind by combining with a verbalizing head v. This approach is not crucial for

the argument, however, and the argument stands within a theory without unaccusative v and

without v at all.

Against ditransitivity 171

Table 3. Levels of ditransitivity for several dative constructions

Level

Lexical Deep Surface

Ditransitives

Monotransitives NO

Causatives NO NO

Unaccusatives NO

NO

5.1. Lexical ditransitivity

Section 2 presented cases in which syntactic and morphosyntactic ditransitivity

is dissociated from lexical ditransitivity, specically, that being a ditransitive

verb is not a necessary condition for appearing in a ditransitive structure or

sentence. The idea is that there are no adjunct indirect objects: once there is

a second internal dative argument, we cannot tell syntactically or morphosyn-

tactically from that extra argument and a selected dative. This dissociation

is problematic for most theories of argument structure and for a central view

within linguistic theory: the projectionist view under which the meaning of a

verb determines the arguments that must appear in a sentence and their inter-

pretation. If it is the verb that semantically and syntactically licenses the two

arguments in the case of double-objects with send, give, tell and put, what is

responsible for their licensing in the case of double-objects with monotransi-

tives like buy, bake, envy, and robar steal and besar kiss? Once we have a

theory of how the licensing proceeds in the latter cases, should not the theory

cover lexical ditransitives as well?

This dissociation is also problematic for Bakers 1988 Uniformity of Theta

Assignment Hypothesis (UTAH) and related generalizations on the relation

between interpretation and position of arguments. UTAH states that identical

thematic relations are represented by identical structural relations. Thematic

relations are usually understood as determined by lexical meaning, and alter-

nations in the realization of arguments are considered the product of syntac-

tic rules, such as incorporation. As such, the hypothesis at most works only

in one direction: identical thematic relations may be represented by identical

base syntax (assuming transformational analyses of argument structure alter-

nations), but it is not the case that identical syntax corresponds to identical

thematic relations in the lexicon, since most ditransitive syntax does not corre-

172 Mara Cristina Cuervo

spond to lexical ditransitivity. As a result, UTAH suffers the same fate as the

projectionist theory.

18, 19

Even if one does not assume UTAH or the projectionist hypothesis, the dis-

sociations should be taken seriously because they pose further challenges to the

notions of verb classes, and even to the notion of transitivity and ditransitivity

as types of structures.

So far, in our discussion of lexical ditransitivity, we focused on the status

of the internal DPs of verbs which are not ditransitive. The reverse of this

case corresponds to ditransitive verbs which appear with less than two internal

arguments. The fact is that every ditransitive verb can appear in sentences with

one object omitted (or even both, in the right contexts), which seems to go

against the very idea of ditransitives selecting two arguments, in the sense of

requiring two arguments.

(28) a. A: Vas

go.2s

a

to

donar

donate

este

this

ao?

year

Will you make a donation this year?

B: No,

no

yo

I

ya

already

di.

gave

No, I have already given (to charity).

b. Le

cl.dat

retiro,

remove.1s

seora?

madam

Shall I take your plate, madam?

It can be argued that those omitted objects are implicit or null objects (either

syntactically active or not; see, e.g., Rizzi 1986; Campos 1986) and therefore

the verb remains ditransitive. The recourse to implicit arguments, however,

requires extreme caution. First, because, as Bosque (1990: 61) warns us, the

18. As an anonymous reviewer points out, the fact that under the low applicative analysis the syn-

tactic relation of the direct object with the verb is different depending on whether there is an

indirect object or not seems to imply that identical thematic relations need not be represented

by identical base syntax either. In turn, this suggests that UTAH cannot be maintained even

as a simple conditional. Note, however, that under Bakers 1996 analysis, Themes are always

projected as the specier of a lower VP irrespective of the projection of an indirect object or

PP complement of V and, therefore, this problem does not arise.

19. We can try to save UTAH by saying that the correlation is indeed biconditional but it is not

strictly about theta roles determined by the verb alone; rather, theta roles are determined

within a structure. The price of this move, however, is ever higher, since then UTAH would

not be a hypothesis about lexical meaning and syntactic structure but about compositional

semantics and syntactic structure. Given that compositional rules are normally understood as

performed on syntactic structures, then it is to be expected that the same thematic relations

would correspond to identical syntactic structures. This, however, is the equivalent of giving

up on the projectionist view that posits syntactic structure as determined and restricted by

semantics, not the other way around.

Against ditransitivity 173

various mechanisms of recovering absent information should not be confused

with structural properties of the heads. Second, this recourse just pushes the

question to why the arguments can be left implicit rather than having to be

overtly realized. Levin (1999) discusses some similar issues with respect to the

internal argument of transitive verbs. She notes that transitive verbs can be di-

vided in two groups according to, among other characteristics, the possibility

of omission of the complement. On the one hand, we have the core transitive

verbs, which are transitive across languages, whose objects are always required

and are always DPs rather than varying between DP and PP: causative pred-

icates such as burn, break, melt. On the other hand, the transitivity of verbs

expressing activities is typically more irregular: it varies intralinguistically and

crosslinguistically (request vs. ask for; look at vs. transitive mirar in Spanish),

the complement can be a DP or a PP (eat the cake, eat at the cake), and it

can behave as a direct argument in one language but as an oblique in another.

These are the non-core transitive verbs. Levin derives the different behaviour

of core and non-core transitive verbs (causatives and non-causatives) from the

way the internal argument is licensed. The obligatory object of causatives is

licensed as an argument of a semantic predicate in the event structure repre-

sentation associated with the verb constant (29a). This object projects onto the

argument structure, which in turn determines the syntactic structure of the sen-

tence. Levin calls this semantic and syntactic licensing.

(29) a. Core transitive: break [ [x act

<MANNER>

] cause [ become [ y

<broken> ] ] ]

b. Non-core transitive: sweep [x act

<SWEEP>

y ] (Levin 1999)

For Levin, the licensing of the object of non-causative verbs, in contrast, is

only semantic licensing, which she represents by adding an underlined vari-

able to the event structure associated with non-core transitives such as sweep

(29b). Semantic licensing depends exclusively on the idiosyncratic meaning

of the constant (root). In other words, semantic licensing by a constant is a

question of compatibility, not a syntactic requirement, and the interpretation

of the object does not derive from a systematic position as an argument in the

lexico-semantic representation. Within my syntactic approach, this means that

the internal argument of non-core transitives is licensed as complement of the

root.

Coming back to ditransitives, there are indications that they behave like non-

core transitives with respect to the licensing of internal arguments. First, unlike

the object of causatives, the objects of ditransitives can be omitted under certain

conditions, as illustrated in (28): ditransitives can appear with one, two or no

arguments (besides the subject). Second, there is variability not only in the

presence of the internal arguments of ditransitives, but also in their syntactic

expression as DP-DP or DP-PP. This variability is seen language-internally in

174 Mara Cristina Cuervo

the dative and locative alternations, and crosslinguistically in the numerous

cases in which a DP-PP structure in one language is expressed as a double-

object, applicative construction in another (see Peterson 2007 for a relevant

survey on cross-linguistic variation in applicative constructions).

Another distinctive behaviour of non-core transitives (and unergatives) noted

by Levin (1999) is that they can appear with out-prexation and an animate

object DP, with the meaning verb more than DP, as in (30a); core-transitives

are excluded from this pattern. Ditransitives can exhibit this pattern just like

non-core transitives, as in (30b) and (30c).

(30) a. I am no slouch in the food department, but she consistently out-

ordered and outate me.

b. I was younger and thinking about how little the widow was actu-

ally giving when she outgave all the rich giving extravagant gifts.

(http://dashboarddrummer.blogspot.com/2005/09/coins.html)

c. In Tarver-Jones III in October 2005, The Magic Man out-

threw Jones 620-320 overall (25 punches per round more) and

out-landed him 158-85.

(http://www.boxingscene.com)

These data suggest that ditransitive verbs are all non-core ditransitives. This

means that the internal arguments of prototypical ditransitive verbs are, in

terms of Levin, only semantically licensed by compatibility with the idiosyn-

cratic meaning of the root, not by the event structure. In syntactic terms, the

internal argument(s) of ditransitives are complements of the root.

The unsteady nature of the expression of lexical ditransitives can be nat-

urally captured if we analyse lexical ditransitives as a sub-class of non-core

transitives: verbs which typically license a relation.

20

This captures the fact

that the two internal arguments in ditransitive constructions relate to each other

and then, as a unit, they relate with the verb. The difference is apparent in

cases of double-objects and their PP variant (31a-b), as opposed to sentences

with a benefactive or locative adjunct (31c-d), in which the direct object has a

privileged, closer relation to the verb, not to the other argument.

(31) a. Peter bought [Stephanie an apple].

b. Peter bought [an apple for Stephanie].

c. Peter [jumped the fence] for Stephanie.

21

20. I refer here to semantic licensing by the meaning of the root and to syntactic composition

(licensing of a complement), leaving aside the exact mechanisms by which these structures

are interpreted by rules of semantic composition.

21. Several languages have non-prepositional variants of these benefactives (Baker 1988; Marantz

1993, Peterson 2007, among many others), which Pylkknen analyses as high-applicatives:

an (extra) argument related to an event (which take a VP or vP complement).

Against ditransitivity 175

d. Peter [bought an apple] in that store.

The idea that lexical ditransitivity does not involve a verb taking two inter-

nal arguments but one makes sense, given that the verbs prototypically ditran-

sitive express a directional movement (either possessive, metaphorical or lit-

eral), their complement specifying the object and, in most cases, the goal of

the movement. From a wide enough perspective, since they typically select a

relation, verbs like put and load are as ditransitive as give, which highlights the

similarity between the proposal that the complement of put is a PP (with a DP

in its specier and a DP as its complement) and that the complement of give in

a double-object construction is an applicative phrase.

The view that ditransitives are a sub-class of transitives, together with the

observation that the complement of ditransitives can be a PP or ApplP a

relation or just a DP an individual also captures the idea (already at least

in Levin 1999 and Marantz 1993) that there is no crucial difference in terms

of licensing between a complement DP and a complement PP.

22

Verbs taking

a specier-less PP as complement (look, think, reside, etc.) are, in this sense,

as transitive as a verb taking a DP complement. In fact, ditransitives belong to

the even more general structural class which includes, as argued for by Levin

1999, transitive and unergative activity and semelfactive verbs.

To sum up, ditransitives are a subgroup of monotransitives, the group which

is compatible with semantically licensing a relation. In turn, semantic licensing

by a verbal root is always licensing of one complement.

23

Simply put, this

amounts to saying that there is no lexical ditransitivity.

24

5.2. Syntactic ditransitivity

The analysis of causative and unaccusative ditransitives in Sections 3 and 4

revealed a different pattern of dissociation with respect to deep and surface

ditransitivity.

22. As an anonymous reviewer points out, of course there are verbs which would take one or the

other type of complement, but that seems to depend on idiosyncratic rather than structural

properties of verbs.

23. This means both that a lexical item (a root) can license at most one complement, and not two,

and that it can only select a complement, but not a specier. Grimshaws (1990) observations

on the fact that subjects of nouns are never obligatory point to the idea that subjects are

not licensed by the (lexical) verb either (Marantz 1984, Kratzer 1996), thus reducing the

licensing possibilities of verbs to internal arguments. In a similar fashion, now the licensing

possibilities of verbs, not being relational elements in themselves, are further reduced to one

internal argument.

24. Lexical is to be understood here as opposed to functional; in this sense the only ditransitive

elements (items that relate two individuals) are functional: Appl and P (see Hale and Keyser

1993, Borer 2005).

176 Mara Cristina Cuervo

Table 4. Levels of ditransitivity for causatives and unaccusatives

Level

Lexical Deep Surface

Causatives NO NO

Unaccusatives NO

NO

Abstracting away from the fact that these are not lexical ditransitives, the

cases in Table 4 amount to a double dissociation between the structural and

morphosyntactic correlates of ditransitivity: there are underlying ditransitive

structures that are not expressed as ditransitive sentences, and there are ditran-

sitive sentences that do not arise from ditransitive structures. Ditransitivity is,

at best, an epiphenomenon.

Given this double dissociation, the only meaningful notion of ditransitiv-

ity would be a deep syntactic notion: a verb that takes two internal argu-

ments. Transformational approaches to ditransitives (Baker 1988; Demonte

1995; Landau 1999; Larson 1988; Masullo 1992; among many others), how-

ever, propose that one of the two internal arguments is not really licensed by

the verb.

25

The proposal that the verb or a prepositional element moves and

merges with a higher verb is the acknowledgment that a simple verb can only

take one argument. This is explicitly proposed by Larson (1988) in the Single

Complement Hypothesis. It was this point that Jackendoff (1990a) reacted so

strongly about; interestingly, it is the aspect of Larsons analysis that had the

deepest consequences for theories of argument structure.

We nd similar ideas in non-transformational approaches: The lexical verb

(the root) always licenses one argument: a relation phrase, whose head is re-

sponsible for the licensing of the two arguments (as in Pylkknens low ap-

plicatives, in Pesetskys prepositional GP analysis, and in small clause analy-

ses [Cummins at al. to appear; den Dikken 1995; Hale & Keyser 1993; Harley

2002; Krifka 2004, among others]).

It seems, therefore, that every previous approach to ditransitives has already

been arguing, showing or implying that no verb takes two arguments; that there

is no syntactic ditransitivity. There are two important characteristics of the anal-

ysis developed here, however, which, taken together, distinguish it from pre-

vious approaches and are crucial to the understanding of ditransitivity. First,

here the two internal arguments are licensed within the same verbal layer (the

25. Similarly, in the decompositional lexico-semantic structures of lexicalist approaches to argu-

ment structure (Grimshaw 1990, Jackendoff 1990b, Levin & Rappaport 1995), it is always

more than one head or predicate responsible for the licensing of the internal arguments (as in

Jackendoffs cause go to

Poss

).

Against ditransitivity 177

root phrase). Second, the analysis makes a crucial distinction between com-

plements that are non-predicational relations (ApplP and transitive PPs) and

predicational complements, such as embedded vPs in causatives, small clauses

and resultatives. This distinction between simple and complex predicates, be-

tween mono-eventive ditransitives and bi-eventive causatives, was necessary to

uncover the dissociation between surface ditransitivity which includes datives

with causatives and deep ditransitivy which does not. Thus, this approach

differs from others which do not make distinctions among (di)transtives, either

presenting all ditransitive sentences as the result of several verbal layers (trans-

formational, incorporation and raising approaches), as having a causative struc-

ture (Hale &Keyser 2002; Harley 2002; Zubizarreta &Oh 2007), as the expres-

sion of low applicatives (Pylkknen 2008) or explicitly assuming no structural

differences between predicational and non-predicational complements (Cum-

mings et al. to appear).

6. Conclusions

Spanish shows that ditransitive sentences can be the morphosyntactic expres-

sion of diverse base structures; in other words, ditransitivity is an epiphe-

nomenon. This is a result consistent with recent work on transitivity which,

fromdiverse perspectives, argues that transitive sentences are the expression of

different lexical structures (Levin 1999) or can correspond to different under-

lying syntactic structures (Cuervo 2008; Folli and Harley 2005; Hale & Keyser

1993, 2002; Nash 2002; Zubizarreta & Oh 2007; among others). In the case of

ditransitivity, however, the problem is much deeper: ditransitivity is only a pre-

theoretical surface phenomenon. In terms of licensing of arguments by verbs,

we are left with no real ditransitivity at the lexical, semantic or syntactic levels.

Why wouldnt there be lexical or semantic ditransitivity? Why cant a verb

select or require two arguments to which it assigns a theta role, in contrast to

verbs which do so with only one argument? I believe the answer to this question

derives from the lack of (compositional) semantic ditransitivity which, in turn,

derives from the impossibility of syntactic (deep) ditransitivity.

At the beginning of this article we mentioned how it is impossible for a for-

mal syntactic theory like the one built within the framework of the Minimalist

Program (or Principles and Parameters, for that matter) to obtain a derivation

in which a head takes two complements. Any formal theory which allows for

two complements (or two XPs) to equally relate to a verb faces the problem

of accounting for the observed structural asymmetries between the two XPs

found in the prepositional and double-object constructions. Spanish shows that

these asymmetries cannot be accounted for by adding linear order to binding

theory (Demonte 1995; Cuervo 2003; contra Jackendoff 1990a). Transforma-

178 Mara Cristina Cuervo

tional approaches have attempted to derive lexical ditransitivity as composi-

tional semantic ditransitivity via syntactic movement, because there was no

way of linking two theta roles to two internal argument positions in argument

or syntactic structure directly. Ironically, all the work demonstrates that it is

impossible to express syntactic or semantic ditransitivity.

This study, and the view that emerges from it, has important implications for

the theory of argument structure. The idea that there are no verbs that select

and license two arguments is the natural and direct consequence of taking bi-

nary branching seriously (no head can license two complements).

26

The fact

that the impossibility of ditransitivity as a type of syntactic structure makes the

existence of real semantic and lexical ditransitivity impossible directly denes

the direction of determination between the lexicon and the syntax: there is no

strong sense in which the lexicon determines syntactic structure, but the other

way around. Possible syntactic structures, determined both by universal princi-

ples (e.g., binary branching) and language-particular selection and restrictions

(associated with functional heads) interact with the lexical meanings of roots.

Ultimately, it is the possible syntactic structures which determine possible ver-

bal meanings. The only semantics of verbs which does not directly depend on

structure, that is, lexical semantics, is drastically reduced to idiosyncratic or

encyclopaedic meaning and, with some limits, to the type of complement with

which it is most compatible.

27

This research suggests that every formal aspect

of verbal meaning which is relevant for syntactic structure is, in fact, semanti-

cally compositional; in other words, that those systematic aspects of meaning

are not lexical but derive from syntax.

University of Toronto

mc.cuervo@utoronto.ca

26. It is, in principle, possible for a verb to take two arguments maintaining binary branching if, as

proposed by Chomsky 1981, a ditransitive verb takes the direct object as its complement and

the indirect object as its specier, the subject being external to this relation. This position was

abandoned, however, or evolved into the split-VP hypothesis by which each internal argument

is licensed by a different layer of V. If internal arguments are arguments of the verbal root (as

argued for by Levin 1999, Nash 2002, and also here) the impossibility of a root taking two

arguments might derive from both binary branching and a restriction on verbalizing heads

that prevents them from merging with a root (a root phrase) that has a specier. Section 5

discussed semantic and syntactic motivations for proposing that the two internal arguments

of ditransitives are licensed below the root. See also Note 23.

27. This approach contrasts with a fully neo-Davidsonian approach such as Borers (2005), since

here objects are licensed by roots directly, without recourse to an additional event predicate

such as Theme or Quantity.

Against ditransitivity 179

References

Alsina, Alex. 1992. On the argument structure of causatives. Linguistic Inquiry 23. 517555.

Baker, Mark C. 1988. Incorporation: A theory of grammatical function changing. Chicago: Uni-

versity of Chicago Press.

Baker, Mark C. 1996. On the structural position of themes and goals. In Johan Rooryck and Laurie

Zaring (eds.), Phrase Structure and the Lexicon, 734. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Barss, Andrew & Howard Lasnik. 1986. A note on anaphora and double objects. Linguistic Inquiry

17. 347354.

Belletti, Adriana & Luigi Rizzi. 1988. Psych-verbs and theta theory. Natural Language and Lin-

guistic Theory 6. 291352.

Bleam, Tonia. 2003. Properties of the double object construction in Spanish. In Rafael Nez-

Cedeo, Luis Lpez & Richard Cameron (eds.), A Romance perspective on language knowl-

edge and use: Selected papers from the 31st linguistic symposium on Romance languages,

233252. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Borer, Hagit. 2005. The normal course of events. New York: Oxford University Press.

Borer, Hagit & Yosef Grodzinsky. 1986. Syntactic cliticization and lexical cliticization: The case

of Hebrew dative clitics. In Hagit Borer (ed.), The syntax of pronominal clitics. San Diego:

Academic Press.

Bosque, Ignacio. 1990. Las categoras gramaticales. Madrid: Editorial Sntesis.

Bruhn de Garavito, Joyce. 2002. La position syntaxique de thme des verbes exprienceur datif.

Revue qubcoise de linguistique 31(2). 137155.

Campos, Hctor. 1986. Indenite object drop. Linguistic Inquiry 17. 354359.

Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on government and binding. Dordrecht: Foris.

Cuervo, Mara Cristina. 2003. Datives at large. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT dissertation.

Cuervo, Mara Cristina. 2008. La alternancia causativa y su interaccin con argumentos dativos.

Revista de lingstica terica y aplicada 46(1). 5579.

Cuervo, Mara Cristina. To appear. Some datives are born, some are made. Selected proceedings

of the Hispanic Linguistics Symposium, Universit Laval, October 2008.

Cummins, Sarah, Yves Roberge & Michelle Troberg. To appear. Lobject indirect en franais:

sens, reprsentations et volution. In Vues sur le franais du Canada. Qubec: Presses de

lUniversit Laval.

Demonte, Violeta. 1994. La ditransitividad en espaol: lxico y sintaxis. In Violeta Demonte (ed.),

Gramtica del espaol, 431470. Mxico, D.F.: El Colegio de Mxico.

Demonte, Violeta. 1995. Dative alternation in Spanish. Probus 7. 530.

den Dikken, Marcel. 1995. Particles: On the syntax of verb-particle, triadic, and causative con-

structions. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fernndez Soriano, Olga. 1999. Two types of impersonal sentences in Spanish: Locative and dative

subjects. Syntax 2(2). 101140.

Folli, Raffaella & Heidi Harley. 2005. Flavours of v: Consuming results in Italian & English. In

Paula Kempchinsky &R. Slabakova (eds.), Aspectual enquiries, 95120. Dordrecht: Springer.

Grimshaw, Jane. 1990. Argument structure. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Hale, Ken & Samuel J. Keyser. 1993. On argument structure and the lexical expression of syn-

tactic relations. In Ken Hale & Samuel J. Keyser (eds.), The view from building 20, 53109.

Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Hale, Ken & Samuel J. Keyser. 2002. Prolegomenon to a theory of argument structure. Cambridge,

Mass.: MIT Press.

Harley, Heidi. 2002. Possession and the double object construction. Linguistic variation Yearbook

2. 3170.

Harley, Heidi. 2006. On the causative construction. Ms., University of Arizona.

Jackendoff, Ray. 1990a. On Larsons treatment of the double object construction. Linguistic In-

quiry 21. 427456.

180 Mara Cristina Cuervo

Jackendoff, Ray. 1990b. Semantic structures. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Jeong, Youngmi. 2007. Applicatives: Structure and interpretation from a minimalist perspective.

Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Kayne, Richard S. 1975. French syntax: The transformational cycle. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT

Press.

Kempchinsky, Paula. 1992. Syntactic constraints on the expression of possession in Spanish, His-

pania 75. 697704.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1996. Severing the external argument from its verb. In Johan Rooryck and

Laurie Zaring (eds.), Phrase structure and the lexicon, 109138. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Krifka, Manfred. 2004. Semantic and pragmatic conditions for the dative alternation. Korean Jour-

nal of English Language and Linguistics 4. 132.

Landau, Idan. 1999. Possessor raising and the structure of VP. Lingua 107. 137.