Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Quality Mauritus

Uploaded by

Ahmad Hafizan0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

59 views17 pagesdfs

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentdfs

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

59 views17 pagesQuality Mauritus

Uploaded by

Ahmad Hafizandfs

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 17

Principals Perceptions of the Use of Total Quality

Management Concepts for School Improvement in

Mauritius: Leading or Misleading?

Jean Claude Ah-Teck, Deakin University, Victoria, Australia

Karen Starr, Deakin University, Victoria, Australia

Abstract: As a small island country, Mauritius is relying on its human capital and innovative hi-tech

industry to ensure future economic viability in the global market. As such, Mauritian education author-

ities are seeking ways to raise educational standards. One idea being canvassed is that Total Quality

Management (TQM) could provide the framework for Mauritian school leaders to deliver imperatives

for change and improvement and to achieve the aim of world-class quality education. This paper

reports the fndings of a research into Mauritian principals current practices in line with TQM tenets

and their perceptions about the usefulness or otherwise of ideas implicit in TQM. The fndings indicate

that whilst principals agree with current progressive notions and thinking compatible with the TQM

philosophy, they have not fully translated them into their practice. The paper identifes challenges and

opportunities worthy of discussion for school improvement in twenty-frst century Mauritius with its

high-tech, world-class ambitions.

Keywords: Quality Education, Total Quality Management (TQM), Educational Leadership, School

Improvement, Mauritius Education System

Introduction

T

HE INCREASINGECONOMICneeds of Mauritius to position itself as an intelli-

gent nation state in the front line of global progress and innovation, increasing pres-

sures to improve the quality of schools, and the shortcomings of the various educa-

tional reforms of the past two decades have prompted education offcials to focus

on school leadership to deliver signifcant change. One idea is that Total Quality Management

(TQM), a leadership and management philosophy used extensively by business enterprises

to compete in a globalised world (Deming, 2000; Oakland, 2003), could provide the school

leadership framework to achieve the governments often-stated aim of achieving world-

class quality education (Ministry of Education and Human Resources, 2006; Ministry of

Education and Scientifc Research, 2003). Whether this assumption is correct is the focus

of this paper. It reports the fndings of research into Mauritian principals receptivity to the

main ideas inherent in TQM.

TQM embraces tenets that are consistent with much current literature about school im-

provement (e.g. Leithwood et al., 2006; Hargreaves and Fink, 2003). Extant research suggests

that TQM has been used to improve the quality of schools in a holistic manner and on a

continuing basis (e.g. Bonsting, 2001; Blankstein, 2004). However, no such research exists

in the Mauritian context.

The International Journal of Learning

Volume 18, Issue 4, 2012, http://www.Learning-Journal.com, ISSN 1447-9494

Common Ground, Jean Claude Ah-Teck, Karen Starr, All Rights Reserved, Permissions:

cg-support@commongroundpublishing.com

Total Quality Management in Education

The philosophy of TQM was developed by Deming and Juran (Deming, 2000; Juran, 1999).

Although TQM was originally intended for industry, Deming argued that his management

principles could equally be applied to the service sector, including education. TQMs strongest

emphases are leadership commitment and support of formal leaders in the quest for quality,

constancy of purpose, quality consciousness, empowerment, continuous improvement and

a systemic approach as a way of organisational life (Mukhopadhyay, 2005). Such ideas are

reinforced by Leithwood et al. (2006) who contend that school leadership should be based

on fexibility, persistent optimism, motivating attitudes and dispositions, commitment and

an understanding of ones actions on the daily lives of others.

De Jager and Nieuwenhuis (2005, p 254) describe the key principles of TQMin education

as leadership, scientifc methods and tools and problem-solving through teamwork. These

three specifc features are linked to form an integrated system that contributes to the organ-

isational climate, [professional learning] and provision of meaningful data with [stakeholder]

service at the centre of it all (see Figure 1). Another important TQMtenet commonly referred

to in the literature is a focus on systemic thinking about the school (e.g. Bonstingl, 2001;

Deming, 2000; Mukhopadhyay, 2005).

Figure 1: Key Principles of TQM in Education (De Jager and Nieuwenhuis, 2005, p 254,

Adapted)

Distributed Leadership

TQMendorses distributed, shared or collective notions of leadership (Gronn, 2000; Mukho-

padhyay, 2005), including an emphasis on teacher leadership (Starr and Oakley, 2008), re-

cognising the importance of collaboration, collective decision-making and teamwork to enable

stakeholders to contribute to the processes of visioning and implementing rather than simply

2

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LEARNING

accepting the formal leaders personal vision (Bush and Glover, 2003). In particular, prin-

cipals, as formal leaders, have a crucial role in creating genuinely shared leadership partner-

ships with teachers, especially in assisting them to learn and grow professionally (Starr and

Oakley, 2008), empowering them to effect decisions autonomously and recognising them

as leaders in their spheres of infuence (Gronn, 2000). It is not diffcult to see the basis of

the current appeal to the idea of distributed leadership as a form of participatory democracy

(Leithwood et al., 2007).

Focus on the Stakeholder

Akey TQMprinciple is the focus on stakeholders satisfaction through meeting and exceeding

their needs and expectations (Sallis, 2002), based on the principle that the stakeholder is the

supreme judge of the educational quality (Deming, 2000; Oakland, 2003). In the TQM

scenario, therefore, the organisational structure and decision-making are inverted so that

principals lead from the bottom up. Accordingly, educational programmes are designed by

teachers and school leaders based on students needs and expectations. This is a fundamental

paradigm shift in the culture of educational leadership, with leaders expected to be less pre-

scriptive and more supportive collaborators with other stakeholders.

TQM also entails a focus on external networks, emphasising cooperation rather than

competition (Deming, 2000; Oakland, 2003). Cooperation with parents, other schools, uni-

versities, future employers and the community enhances satisfaction and loyalty. In this way,

an effective chain of stakeholders is built through participation in decisions regarding pro-

gramme design and delivery improvements.

Commitment to Continuous Improvement

TQM espouses continuous improvement of knowledge, processes, products and services

(Bonstingl, 2001; Oakland, 2003; Sallis, 2002). Schools that are quality orientated engage

in continuous innovation and change that better meet their stakeholders expectations and

that support learning for students as well as teachers and leaders (Gandolf, 2006). Achieving

quality is a never-ending journey of improvement of people and processes (Bonstingl, 2001;

Sallis, 2002; Mukhopadhyay, 2005), realised through multi-functional teams, stakeholder

feedback, staff empowerment, and data collection methods and measurement (rather than

inspection regimes) to build quality into the systemand processes (Deming, 2000). Ultimately,

the focus of continuous quality improvement is on the optimisation of both individual and

collective potential within an organisation.

Leadership Based on Data

TQM aims at proactive and responsive (as opposed to reactive) decision-making based on

data and evidence (Deming, 2000; Mukhopadhyay, 2005). Importantly, it suggests developing

a data culture in the school which facilitates participative decision-making, to provide

transparent leadership and more reliable, locally-derived evidence to enable determinations

and problem solving (Deming, 2000).

3

JEAN CLAUDE AH-TECK, KAREN STARR

Professional Learning

Implementing TQM in schools calls for a high degree of delegation and decentralisation re-

quiring that all employees receive relevant professional learning opportunities. Professional

development should be ongoing and respond to practitioners needs in order to explore new

educational thinking and enhance group effectiveness (Wilms, 2003). To be true to Demings

philosophy, professional learning should also serve to create and promote a working envir-

onment in which collaboration and involvement of teachers fromdifferent subject disciplines

and departments prevail (Berry, 1997).

Teamwork

Deming (2000) is adamant of the need to break down barriers between departments and ab-

olish competition within the organisation. Thus, to build an effective TQMculture, teamwork

and cooperation should be extended throughout the school (Sallis, 2002). One of the most

prominent features of TQM concerns the restructuring of the school into semi-autonomous

or self-directed work teams, that communicate laterally while remaining connected to internal

and external stakeholders (Lycke, 2003; West-Burnham, 2004).

Focus on the System

TQMis based on systems thinking an analysis of the interrelationships and interdependence

of constituent units and sub-systems and interpretation of these interactions in predicting

what may happen in other parts of the system if certain changes are made elsewhere (Muk-

hopadhyay, 2005). In essence, systems thinking ensures that the intelligent school is a

living organisma dynamic systemthat is more than just the sumof its parts (Groundwater-

Smith, 2005, p 2).

Cultural Change

The TQM paradigm would represent a cultural change and fundamental shift in thinking

about leadership in many, if not most, Mauritian schools which adhere to traditional, hier-

archical conceptions of leadership (Gronn, 2003; Spillane, 2006). To be useful in education,

school leaders must work with stakeholders to understand clearly those TQM elements that

are most pertinent for quality improvement and customise them to suit their contexts.

Research Methodology

A mixed methods research was employed to investigate principals views about school and

systemic improvement and the usefulness or otherwise of TQM in raising quality (including

equity) in Mauritian schools. This paper reports specifcally on qualitative aspects of the

study related to data collected by means of semi-structured interviews conducted with a

purposive sample of six principals. (The quantitative data collected through a countrywide

questionnaire survey of all primary and secondary school principals will be the focus of a

forthcoming research article.) The research questions were:

4

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LEARNING

Do principals perceive their current leadership practices for school improvement bear

resemblance with the TQM philosophy?

Do principals perceive that TQM-like tenets could be usefully adapted for school im-

provement purposes?

Six schools were involved (two primary and four secondary schools), representing diversity

of sector, level of schooling, gender, location and socio-economic status of the enrolling

families. Three schools were in urban areas and three were rural, three were state and three

Catholic schools (also controlled by Mauritian education authorities). Two principals were

females, four were males. One school had children predominantly fromprofessional families,

another with a large population from working class families, and the others with students

from mixed backgrounds. Difference between schools was seen as valuable for the research

in exploring TQMs relevance and applicability in divergent contexts.

The qualitative phase of the research was an exercise in grounded theory building (Glaser

and Strauss, 1967). In this approach, theory emerges from the data gathered through an in-

ductive process whereby emerging research insights are analysed and continually tested,

producing further evidence and/or new theoretical insights (Corbin and Strauss, 2008). The

iterative processes of developing claims and interpretations is responsive to research situations

and the multiple layers of meaning produced by the people in them (Gray, 2009). Open

coding identifed several categories of causal conditions, phenomena, strategies, and con-

sequences. Axial coding identifed and classifed the data and enabled connections between

categories to be made, while selective coding refned the integration of categories.

Issues of reliability and validity were addressed using Guba and Lincolns (1989) set of

standards for establishing the quality or trustworthiness of data in qualitative research. The

participating principals were allowed to listen to their audio-recorded responses and read

the observational feld notes taken immediately after the interview, and were asked if these

refected what they intended them to mean. Transcripts or analysed results were taken back

to the interviewparticipants so that they could themselves legitimately judge the credibility

of the results. Transferability was enhanced by providing a detailed description of the re-

search context and the assumptions that were central to the research. Another technique was

the triangulation or multiple methods of data collection and analysis, which strengthens

dependability as well as credibility (Merriam, 1998).

Findings, Discussion and Implications for School Leadership

The data analyses and fndings fromthe interviews with the Mauritian principals are categor-

ised under the TQM principles identifed in the literature review, which are used as the or-

ganising framework to highlight themes. Because of the interdependence of the TQMprinciple

of cultural change with the other principles, the data are not analysed separately with ref-

erence to cultural change, but are captured and subsumed within the other principles/headings.

Distributed Leadership

A major fnding is that while the Mauritian principals were comfortable with the current

notion of distributed leadership and voiced compellingly that they put it into practice, in

many instances, their comments revealed contradictions to a genuinely collaborative approach.

These principals did not seem to trust a large array of stakeholders within the school com-

5

JEAN CLAUDE AH-TECK, KAREN STARR

munity. Instead, they placed more professional responsibility in the hands of those who

would buy into their vision and believe in and support their own ways of seeing and doing

things. It was a vision imposed from above and there was no readiness to move forward

towards change that involved everyones contribution. For example, principals stated:

Although I would describe my leadership style as democratic, sometimes I still need

to impose. These policy guidelines enable me to exercise control. The guidelines

also ensure that everybody knows exactly what is expected of them. (PA)

You cannot be on top of them (teachers). You have to be in the middle of them and

share your vision, and make it accepted in a democratic way so that they feel they have

ownership of it and they will therefore be more inclined to be committed to that vision.

(PA)

We empower all staff to make decisions and even hold them accountable for exercising

initiatives aligned with the schools common mission or educational purpose. The

idea is to give staff a sense that they have a real say in things that matter to them and

that affect them most. (PF)

These comments suggest an underlying autocratic leadership style which served principals

own interests.

Moreover, the responses of Mauritian principals infer that the formal school leader should

remain responsible and accountable and retain the right of veto in the strategic direction of

the school. The respondents therefore had an erroneous understanding which suggested that

that those in charge of the system are the only ones who could change that system by their

presence and commitment. It has to be noted that formal leaders are not the only agents of

change (Fullan, 2007). If leadership were truly distributed and decisions were made demo-

cratically, then everyone within the teamwould be a powerful agent of change. By and large,

principals agreed to the importance of promoting collaborative approaches and ensuring that

decision-making involved those most affected by outcomes, yet they remained evasive when

prompted into elaborating the sorts of decisions involving stakeholders.

In the conservative Mauritian context where school leadership is predominantly equated

with the actions of principals who are the sole leaders and managers of schools, the educa-

tional system expects and demands that they are in control. Principals are squeezed between

current progressive notions of school leadership and very autocratic government demands

for certain policies to be implemented, with principals being responsible for this (despite

government ideas about how school improvement might occur). They might wish to pursue

distributed leadership styles but change is always painstakingly slowand government demands

immediate (Hargreaves and Fink, 2003; Starr, in press). Thus they are left with no option

than to use their power and formal position to demand conformity from staff in autocratic

ways.

The distributed leadership perspective is borne out by much current literature in educational

leadership (e.g. Leithwood et al., 2006; Silins and Mulford, 2002). Moreover, [s]ustainable

leadership is distributed leadership as an accurate description of how much leadership is

already exercised, and also as an ambition for what leadership can, more deliberately, become

(Hargreaves, 2007, p 225). Surely, distributed leadership is an idea whose time has come

6

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LEARNING

(Gronn, 2000, p 333). Mauritian education authorities recognise the need for change through

its espoused support for TQM-like tenets, although demands for improvement appear to

overlook this aspect of the philosophy.

Focus on the Stakeholder

In this Mauritian study, principals perceived that their schools were not only focusing on

students and tapping into the resources of their staff in their educative mission, but were also

developing links with parents, other educational institutions, businesses and the community.

However, in practice principals main focus was to secure stakeholders attention through

marketing and public relation strategies, not through collaboration in the schools operations,

decision-making or governance. There were several instances of parents, for example, being

actively dissuaded from participating in decision-making. For example:

We believe that we have a better perspective than parents of what is necessary for the

school and helpful for their children. So we cant allow parents to intrude too much in

important decision-making in which they might not have the competence, anyway.

(PC)

Some parents use their infuence to control what goes on here when they volunteer, and

what decisions are made in school committees. They just violate their boundaries. Do

you think I can let this happen? (PF)

In general, it can be concluded that in all the sampled schools, parents and students as primary

stakeholders have less professional say than educators, consistent with provider capture,

a widespread phenomenon coined by Gannicott (1997) whereby schooling is controlled by

the people who produce it rather than by those who consume it. It is easy for the needs

and demands of central education authorities to take precedence in policy making and regu-

latory activities which result in their all encompassing bureaucratic arms controlling the

work of schools and in turn keeping stakeholders at arms length to abide by the decisions

of school leaders whose vested power allows them to act as intermediaries in implementing

decisions from above.

Yet, there is substantial evidence from the literature that supports the building of relation-

ships with all stakeholders inside and outside the school, with school leaders viewing

themselves as collaborators of one another and of teachers, students, parents, businesses and

community members (Bonstingl, 2001). This is perceived as essential for ensuring sustainable

improvements in quality performance (Deming, 2000; Oakland, 2003), and developing a

learning organisation (Gandolf, 2006; Senge et al., 2000) in which fear by gratuitous bur-

eaucratic rules and regulations is driven out (Deming, 2000) in favour of genuine distributed

leadership resulting in empowerment of people at all levels.

Commitment to Continuous Improvement

Like the rest of the world, schools in Mauritius are changing signifcantly. School improve-

ment, education reformand similar themes of renewal have been an integral part of Mauritian

education for the past twenty years and beyond if we consider earlier waves of reform

7

JEAN CLAUDE AH-TECK, KAREN STARR

(Ministry of Education and Scientifc Research, 1998, 2001a, 2001b, 2003). Learning how

to successfully implement changes in the current educational and economic contexts is par-

ticularly important, especially at a time of a huge variety of initiatives and innovations and

when there are competing government reforms being promoted in schools concurrently.

The empirical evidence in this study points out, however, that school leaders have a

mounting task in managing the level of resistance to change and in aligning teachers work

towards their vision and government objectives (see also Starr, in press). Some indicative

comments included:

Any school improvement plan should include goals that are aligned with the ministrys

initiatives. We dont have much choice, do we? Also, parents, students and other

stakeholders have conficting interests and demands, and we have to try to please

everybody. (PD)

Every fve years or so, a new government is elected, bringing a new educational reform

which contradicts and substitutes an earlier reformby the old regime. Anewgovernment

[thinks it] has to be seen to be doing things differently but they dont even consult

us. Here we go, abiding by orders fromabove and starting all over again. The situation

is really chaotic. (PF)

The study reveals that the heavy hand of government often imposes educational reforms

on schools, with school leaders acting as the gate-keepers of such major change agendas

(see also Starr, in press). Principals, however, are not partners in policy decisions. The failure

or inability of Mauritian principals to fully commit themselves to the TQM philosophy and

to achieve quality and genuine school improvement could largely be explained by autocratic

government demands for policy implementation, with principals positioning themselves as

middle managers and abiding by orders received from the upper echelons even though the

government itself espouses distributed leadership and a TQM approach. Principals feel they

have to be authoritarian and coercive to some extent because often policy change is unpop-

ular and major change is diffcult to lead (Starr, in press). This is exacerbated by the shifting

political interventions as the Mauritian government changes, with each newregime bringing

its own assortment of innovations which are often in confict with earlier ones. As Hargreaves

and Fink (2003, p 693) argue, [e]ducational change is rarely easy to make, always hard to

justify and almost impossible to sustain. It is perhaps no wonder that the structure of

schooling and practice of teaching in Mauritius have remained remarkably stable over decades

amidst radical but ephemeral reforms (see also Evans, 2001). However, if TQM demands

certain compliant behaviours at the micro level, then these should also occur at the national

level. The government needs to make overtures to trust schools and their principals.

Leadership Based on Data

The use of data, including benchmarking, to measure work quality and refnement was not

an area of strength of the principals. The principals responses are in agreement with the

observations made by Evans (2007) that measurement, analysis, and knowledge management

efforts are often the least advanced of the quality dimensions within organisations. Principals

lack of time and lack of confdence due to their inadequate knowledge of statistics were ad-

8

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LEARNING

ditional barriers to the use of tools and techniques for systematic data collection and analysis,

again corroborating with other research fndings (e.g. Schildkamp and Kuiper, 2010; Shen

and Cooley, 2008). Principals commented:

I think there is nothing wrong with using questionnaire surveys and other formal means

to gather information about peoples needs or complaints. The problem is that it takes

time and we have no time for that. We are also not trained to collect data systemat-

ically, let alone to analyse them statistically. (PE)

My staff will have to be trained to construct questionnaires to collect data and they will

need to have some knowledge of statistics to be able to analyse the information. But

not everyone is statistically minded and I guess that it will be hard for all people to

think in statistical terms. The [other] problem is that it will take so much time to carry

out systematic data collection. (PC)

Thus, decision-making based on facts and evidence, as a requirement of TQM, was not

totally substantiated in the Mauritian study. Yet there was strong agreement among the

principals as to potential advantages that would accrue fromdata usage for decision-making

purposes. Principals also believed, however, that to place an overwhelming importance on

data in making educational choices and decisions is to potentially deny the importance of

people, who are at the heart of the school improvement process, and their professional intuition

and judgement.

Hence, there is an urgency to determine the current level of leaders [and teachers] ex-

pertise in accessing, generating, managing, interpreting, and acting on data (Knapp et al.

2006, p 39). Care will have to be taken that unintended or undesirable effects do not occur

as a result of an overemphasis on data-driven decision-making for example, reduced mo-

tivation among teachers due to extra workload or narrow focus on the tested curriculum

(Schildkamp and Teddlie, 2008).

Professional Learning

Professional learning, together with distributed leadership, are the areas of leadership practice

in the sampled schools that were found to be the least aligned with the TQM paradigm. Ac-

cording to principals, professional learning opportunities were made available to staff in the

form of staff development programs for heads of department and heads of year, which they

claimed they were conducting themselves. One principal explained:

Staff development is effected via staff meetings and general workshops From

time to time, we organise whole-staff sessions and in-service sessions for heads of de-

partment and heads of section when either myself or my assistant would take the lead

to address issues as wide-ranging as classroom management, discipline, assessment,

teaching of mixed-ability classes. (PD)

However, the true purpose of these in-service training sessions seemed to be ad hoc orient-

ation sessions to disseminate school protocols and policies and, therefore, cannot be called

professional learning as such. Effective professional learning should instead be purposefully

9

JEAN CLAUDE AH-TECK, KAREN STARR

directed and focused on curriculum or pedagogy or both (Garet et al., 2001), and concerned

with creating and sustaining a school climate that empowers teachers to be the architects of

their own professional development and to foster their leadership capacity (Cherubini, 2007).

In other words, situational demands should determine professional development, and not

necessarily generic needs as the principals in this study suggested. A decline in resistance

to participation in professional development by educators was noted when the learning

happened in classroom contexts (see also Gallucci, 2008). Hence, in general, professional

learning does not have to stem from an expert, but rather requires collaborative efforts in-

volving teachers with a genuine desire to improve their practice by engaging with colleagues

and sharing ideas with knowledgeable others (Wayman, Jimerson and Cho, 2011).

Principals reported that teachers in their schools received support through in-service de-

partmental workshops supervised by heads of department with the aimof continually improv-

ing their knowledge and skills. However, learning which is compartmentalised into artifcial

subject felds is contrary to Demings systemic view of an organisation where quality is en-

hanced by demolishing barriers between traditional departments and promoting cooperative

ways of working. Improvement of student learning is an interdisciplinary task (Berry, 1997).

The interdependencies of real life which involve the combined use of a number of skills,

should suggest a direction for school activities such as mathematics, languages, science and

social studies but there was no evidence of such integrated learning and cross-discipline

collaborative endeavours. This line of reasoning is consistent with research evidence on or-

ganisational learning which suggests that connecting people who speak from diverse per-

spectives and experiences is essential to organisational health and effectiveness (Senge,

2006).

Teamwork

This study fnds that current Mauritian school leadership practice, at least in the sampled

schools, is focused on the formal leader and ignores the leadership capacity and potential

that exists throughout the school. Morally and practically, the emphasis on the leader is

inappropriate and needs to be replaced by recognition of leadership as a collective capacity

that is refected in structures, processes and relationships (West-Burnham, 2004, p 1). Teams

are likely to be a powerful way of developing potential and capacity. The most prominent

feature is that of teams communicating laterally and their closeness to internal and external

stakeholders (Lycke, 2003). Teams can be viewed as nurseries where there are abundant

opportunities to develop and learn the artistry of leadership in a secure and supportive envir-

onment (West-Burnham, 2004, p 5).

Principals adhered to a very traditional conception of teamwork where the school leader

or another manager would take control and preside over the destiny of the group of people

assembled for a specifc function or project. In all cases, formal school leaders were adamant

that they had to retain the right to oversee the strategic direction of the school or that they

were the only ones in charge of the system. One principal made it clear:

A parent could make inputs about school matters to the committee and the chairperson

would submit the input to the school leadership team. Committee members know,

however, that their powers are restricted and that the school [leadership] team has the

fnal say on policy matters. (PF)

10

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LEARNING

Principals made contradictory comments about an emphasis on building effective working

relationships, however. In general, while principals claimed their penchant to collaborative

approaches centred on issues such as curriculum pedagogy and assessment, their very own

comments revealed a major contradictionleadership was not distributed but was rather

concentrated at the top and was very much concerned with the implementation of policy

directives.

A most obvious departure from Demings notion of teamwork is that most principals felt

that professional learning ought to be a matter of the individual teachers own responsibility.

This was evident in comments such as:

Teachers are adults who know how to take care of themselves. They know what they

need to do to improve their own education and personal development. (PB)

It is required of teachers to put in all effort in the planning and preparation of their les-

sons and to be responsible for their own professional and personal development so as

to teach more effectively. (PE)

Deming (2000) makes a distinction between the impact of individual learning and that of

team learning, and recommends breaking down barriers between departments within the

organisation. If teams learn, they become micro-cosmic for learning throughout the organ-

isation. Teamaccomplishments can set the tone and establish standards for learning together

for the larger organisation. The key point is that teamwork recognises and uses complexity

in a way that individuals are unable to (Oakland, 2003).

Focus on the System

Another signifcant fnding in this study is that none of the principals assumed their leadership

role as a systemic one, but were rather concerned and focused on what was happening in

their own schools as stand-alone sites. Whatever the publicly stated vision of the participating

schools, in reality, principals were functioning in a mode which conceived their leadership

as bounded by their own interests or those of their schools. Collective responsibility in the

Mauritian educational system was a far cry from reality and, at least in the sampled schools,

the impetus to compete and succeed at the expense of other schools remained strong. Prin-

cipals also perceived that any gestures of assistance to other schools would be cynically re-

jected. As one principal explained:

Of course, we could have reached out to lowperforming schools to assist themin terms

of teaching methods, learning resources and management practice. As a leading

school, we could have set the example, but there is also the problem of other schools

not wanting to be shown how to do things. They would surely be saying say: But who

are you? or Do you think you are that perfect? (PA)

There is the suggestion in the above comment that there are problems with the teachers,

students and their parents in lower achieving schools, which are condemned and marginalised.

The reservation set by the principal is also an indication that some schools perceived them-

selves as quality schools, but did not see themselves having a role to produce a quality

education system at the national (or international) level.

11

JEAN CLAUDE AH-TECK, KAREN STARR

Mauritius is such a small country that the educational system can be viewed as a single

social organisation composed of many schools, similar to a school district in some other

countries. This larger system needs to constantly improve as an entity if Mauritius is to raise

educational standards over the long term. Besides, raising a countrys economic competitive-

ness necessitates curtailing competition in education, not increasing it (Caro, 2010). The

way forward in the drive towards total quality is to improve constantly and forever the system

by building partnerships of trust and cooperation among educational institutions to support

each others continuous improvement efforts. There is a burgeoning literature indicating that

partnerships can signifcantly improve the learning experience, achievement and life chances

of students (e.g. Higham and Yeomans, 2005; Lumby and Morrison, 2006). Such networks

of support at the macro level are essential for learning and improvement to be optimised at

the micro level (Bonstingl, 2001).

If school leaders, policy makers and central education authorities in Mauritius obstinately

continue to envision the educational leadership arena as delimited by the traditional structure

in which single schools function autonomously, then they will not refect cooperation and

mutuality in trusting partnerships with alignment of goals and values (Lumby and Morrison,

2006). Neither will the Mauritian educational systemliberate itself fromits present ingrained

competitive orientation which blatantly applauds the reinforcement of stratifed prestigious,

so-called star schools to the detriment of a signifcant majority of students in weaker

schools. Real educational leadership would be for school leaders and central education au-

thorities to challenge the so-called star-school system as an issue of social injustice. Research

suggests benefts for all students and staff through schools networking, clustering, merging

and connecting in tangible ways (Starr and White, 2008). By pooling resources and agreeing

on some degree of mutual development, schools could create new possibilities in ways that

would not otherwise have been possible.

Implications for Further Research

To the best of our knowledge, this is the frst ever study on TQM in primary and secondary

education in Mauritius at the national level. As there are no studies with which to compare

the fndings of the present study, they are certainly worth exploring in further studies. Future

research can improve upon the fndings of the present study by using larger samples of

principals and raters other than principals, such as deputy principals, heads of year group,

heads of department, teachers, students and parents. This type of research can potentially

triangulate the fndings of the present study, provide more comprehensive fndings about

successful school leadership practices and offer a richer and more accurate description of

leadership reality in Mauritius.

Conclusion

By and large, the fndings reported in this study paint a rather gloomy picture of school

leadership in Mauritius in relation to the application of effective practices embedded within

the TQM paradigm despite government aims. While critics might point out that TQM is an

ideal which is hard to achieve, it precisely serves the purpose of an ideal: that is, to provide

a benchmark and goal against which to measure progress. Principals responses in this study

indicate that TQM discourses are accepted and even applauded, but their fulfllment in

12

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LEARNING

practice will require considerable adjustments to current implicit leadership theory and

practices. However, education authorities reaffrm the governments vision of Mauritius as

a world player in the vanguard of global progress and innovation and to make the Mauritian

economy more internationally competitive, and hence a systematic initiative for quality im-

provement is required even though its implementation may be diffcult.

13

JEAN CLAUDE AH-TECK, KAREN STARR

References

Berry, G. (1997). Leadership and the development of quality culture in schools. International Journal

of Educational Management, 11(2), 5264.

Blankstein, A. M. (2004). Failure Is Not an Option: Six principles that guide student achievement in

high-performing schools. Thousand Oaks, CA: HOPE Foundation/Corwin Press.

Bonstingl, J. J. (2001). Schools of Quality (3

rd

ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Bush, T. and Glover, D. (2003). School Leadership: Concepts and evidence. UK: National College

for School Leadership.

Caro, J. (2010). The winner takes it all. Education Review, May, 2010, 1819.

Cherubini, L. (2007). Acollaborative approach to teacher induction: Building beginning teacher capacity.

Paper presented at the Association of Teacher Educators Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA.

Corbin, J. and Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of Qualitative Research (3

rd

ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

De Jager, H. J. and Nieuwenhuis, F. J. (2005). Linkages between total quality management and the

outcomes-based approach in an education environment. Quality in Higher Education, 11(3),

251260.

Deming, W. E. (2000). The NewEconomics for Industry, Government, Education (2

nd

ed.). Cambridge,

MA: MIT Press.

Evans, J. R. (2007). Impacts of information management on business performance. Benchmarking:

An International Journal, 14(4), 517533.

Evans, R. (2001). The Human Side of School Change: Reform, resistance, and the real-life problems

of innovation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Fullan, M. (2007). The New Meaning of Educational Change (4

th

ed.). New York, NY: Teachers

College Press.

Gallucci, C. (2008). Districtwide instructional reform: Using sociocultural theory to link professional

learning to organizational support. American Journal of Education, 114, 541581.

Gandolf, F. (2006). Can a school organization be transformed into a learning organization? Contem-

porary Management Research, 2(1), 5772.

Gannicott, K. (1997). Taking education seriously: A reform program for Australias schools. St. Le-

onards, NSW: Centre for Independent Studies.

Garet, M. S., Porter, A. C., Desimone, L., Birman, B. F. and Yoon, K. S. (2001). What makes profes-

sional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. American Educa-

tional Research Journal, 38(4), 915945.

Glaser, B. and Strauss, A. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for qualitative re-

search. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Gray, D. E. (2009). Doing Research in the Real World (2

nd

ed.). London: Sage.

Gronn, P. (2000). Distributed properties: A new architecture for leadership. Educational Management

and Administration, 28(3), 317338.

Gronn, P. (2003). The New Work of Educational Leaders: Changing leadership practice in an era of

school reform. London: Paul Chapman.

Groundwater-Smith, S. (2005). Through the keyhole into the staffroom: Practitioner inquiry into school.

AHIGS Conference. Shore School.

Guba, E. G. and Lincoln, Y. S. (1989). Fourth Generation Evaluation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Hargreaves, A. (2007). Sustainable leadership and development in education: Creating the future,

conserving the past. European Journal of Education, 42(2), 223233.

Hargreaves, A. and Fink, A. (2003). Sustaining leadership. Phi Delta Kappan, 84(9), 693700.

Higham, J. J. S. and Yeomans, D. J. (2005). Collaborative Approaches to 1419 Provision: An evalu-

ation of the second year of the 1419 Pathfnder Initiative. Nottingham: Department for

Education and Skills (DfES).

14

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LEARNING

Knapp, M. S., Swinnerton, J. A., Copland, M. A. and Monpas-Huber, J. (2006). Data-informed Lead-

ership in Education. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Center for the Study of

Teaching and Policy.

Leithwood, K., Day, C., Sammons, P., Harris, A., and Hopkins, D. (2006). Successful School Leadership:

What it is and how it infuences pupil learning. London: DfES.

Leithwood, K., Mascall, B., Strauss, T., Sacks, R., Memon, N., and Yashkina, A. (2007). Distributing

leadership to make schools smarter: Taking the ego out of the system. Leadership and Policy

in Schools, 6, 3767.

Lumby, J. and Morrison, M. (2006). Collective leadership of local school systems: Power, autonomy

and ethics. Paper presented at the Commonwealth Council for Educational Administration

Conference, Lefkosia, Cyprus, 1217 October.

Lycke, L. (2003). Team development when implementing TPM. Total Quality Management, 14(2),

205213.

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education (2

nd

ed.). San

Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Ministry of Education and Human Resources (MEHR) (2006). Quality Inititiatives for a World Class

Quality Education. Port Louis, Mauritius: MEHR.

Ministry of Education and Scientifc Research (MESR) (1998). Action Plan for a New Education

System in Mauritius. Port Louis, Mauritius: MESR.

Ministry of Education and Scientifc Research (MESR) (2001a). Ending the Rat Race in Primary

Education and Breaking the Admission Bottleneck at Secondary Level: The Way Forward.

Port Louis, Mauritius: MESR.

Ministry of Education and Scientifc Research (MESR) (2001b). Reforms in Education: Curriculum

Renewal in the Primary Sector. Port Louis, Mauritius: MESR.

Ministry of Education and Scientifc Research (MESR) (2003). Towards Quality Education for All.

Port Louis, Mauritius: MESR.

Mukhopadhyay, M. (2005). Total Quality Management in Education (2

nd

ed.). New Delhi: Sage.

Oakland, J. S. (2003). Total Quality Management: Text with cases (3

rd

ed.). London: Elsevier.

Sallis E. (2002). Total Quality Management in Education (3

rd

ed.). London: Kogan Page.

Schildkamp, K. and Kuiper, W. (2010). Data-informed curriculumreform: Which data, what purposes,

and promoting and hindering factors. Teaching and teacher education, 26(33), 482496.

Schildkamp, K. and Teddlie, C. (2008). School performance feedback systems in the USA and in the

Netherlands: A comparison. Educational Research and Evaluation, 14(3), 255282.

Senge, P. M. (2006). The Fifth Discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization (Revised

ed.). New York, NY: Doubleday/Currency.

Senge, P., Cambron-McCabe, N., Lucas, T., Smith, B., Dutton, J. and Kleiner, A. (2000). Schools That

Learn: A ffth discipline feldbook for educators, parents, and everyone who cares about

education. New York: Doubleday/Currency.

Shen, J. and Cooley, V. E. (2008). Critical issues in using data for decision-making. International

Journal of Leadership in Education, 11(3), 319329.

Silins, H. and Mulford, B. (2002). Leadership and school results. In Leithwood, K. and Hallinger, P.

(eds.). Second International Handbook of Educational Leadership and Administration (pp

561612). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Spillane, J. (2006). Distributed Leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Starr, K. (in press). Principals and the politics of resistance to change. Educational Management, Ad-

ministration and Leadership: 39/6, November 2011. Sage, UK.

Starr, K. and Oakley, C. (2008). Teachers leading learning: The role of principals. The Australian

Educational Leader, 30(4), 3436.

Starr, K. and White, S. (2008). The small rural school principalship: Key challenges and cross-school

responses. Journal for Research in Rural Education, 23(5), 112.

15

JEAN CLAUDE AH-TECK, KAREN STARR

Wayman, J. C., Jimerson, J. B. and Cho, V. (2011). Organizational considerations in educational data

use. Paper presented at the 2011 meeting of the American Educational Research Association,

New Orleans, LA.

West-Burnham, J. (2004). Building Leadership CapacityHelping Leaders Learn: An NCSL thinkpiece.

UK: National College for School Leadership.

Wilms, W. W. (2003). Altering the structure and culture of American public schools. Phi Delta Kappan,

84(8), 606615.

About the Authors

Jean Claude Ah-Teck

Deakin University, Australia

Prof. Karen Starr

Deakin University, Australia

16

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LEARNING

Copyright of International Journal of Learning is the property of Common Ground Publishing and its content

may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express

written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Early Childhood Care and Education Framework India - DraftDocument23 pagesEarly Childhood Care and Education Framework India - DraftInglês The Right WayNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- MAP ManualDocument239 pagesMAP ManualGeraldValNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- MCF Iyef Project ProposalDocument9 pagesMCF Iyef Project ProposalKing JesusNo ratings yet

- Classroom Communication and DeversityDocument253 pagesClassroom Communication and DeversityNgo Ngoc HoaNo ratings yet

- Statistical TreatmentDocument16 pagesStatistical TreatmentMaria ArleneNo ratings yet

- Primer On The PhilsatDocument24 pagesPrimer On The PhilsatOzkar KalashnikovNo ratings yet

- HRM ModuleDocument92 pagesHRM ModuleShyam Khamniwala100% (1)

- Agile Processes in Software Engineering and Extreme ProgrammingDocument311 pagesAgile Processes in Software Engineering and Extreme Programmingalfonso lopez alquisirez100% (1)

- Unit 2 Reflection-Strategies For Management of Multi-Grade TeachingDocument3 pagesUnit 2 Reflection-Strategies For Management of Multi-Grade Teachingapi-550734106No ratings yet

- Esp6 - q2 - Mod7 - Paggalang Sa Suhestiyon NG KapwaDocument27 pagesEsp6 - q2 - Mod7 - Paggalang Sa Suhestiyon NG KapwaAnna Liza B.Pantaleon100% (2)

- NatorpDocument1 pageNatorpIgnacio RojasNo ratings yet

- BBB PosterDocument1 pageBBB PosterAhmad HafizanNo ratings yet

- SamplingDocument21 pagesSamplingAhmad HafizanNo ratings yet

- Research Design: For Social ScienceDocument26 pagesResearch Design: For Social ScienceAhmad HafizanNo ratings yet

- Jack and The Beanstalk Tugas Narrative InggrisDocument2 pagesJack and The Beanstalk Tugas Narrative InggrisDARANo ratings yet

- Spi Bil 8 2016Document30 pagesSpi Bil 8 2016Anonymous 9lODNg100% (2)

- Amalan Dan Manfaat YES ALTITUDEDocument17 pagesAmalan Dan Manfaat YES ALTITUDEsaemahNo ratings yet

- Anti VirusDocument1 pageAnti VirusAhmad HafizanNo ratings yet

- Harta Awam 2Document17 pagesHarta Awam 2Ahmad HafizanNo ratings yet

- Celebration of The Independence Day in My School EssayDocument5 pagesCelebration of The Independence Day in My School EssayAhmad Hafizan44% (9)

- Audacity ManualDocument20 pagesAudacity ManualAhmad HafizanNo ratings yet

- Flyers Antivirus 3Document2 pagesFlyers Antivirus 3Ahmad HafizanNo ratings yet

- Bahan Latihan VLE-1Document6 pagesBahan Latihan VLE-1Roziah Md AminNo ratings yet

- Jadual Dorm Yaaser 2014Document2 pagesJadual Dorm Yaaser 2014Ahmad HafizanNo ratings yet

- Harta Awam 2Document17 pagesHarta Awam 2Ahmad HafizanNo ratings yet

- Nota Kuliah GeoDocument118 pagesNota Kuliah GeoAhmad HafizanNo ratings yet

- Farewell PartyDocument2 pagesFarewell PartyAhmad HafizanNo ratings yet

- Year2 Mat HSPDocument5 pagesYear2 Mat HSPazkoko09No ratings yet

- Farewell PartyDocument2 pagesFarewell PartyAhmad HafizanNo ratings yet

- Cleanliness CampaignDocument2 pagesCleanliness CampaignAhmad Hafizan100% (1)

- PengurusanDocument9 pagesPengurusanAhmad HafizanNo ratings yet

- Kuli Ah IntroDocument16 pagesKuli Ah IntroAhmad HafizanNo ratings yet

- Cleanliness CampaignDocument2 pagesCleanliness CampaignAhmad Hafizan100% (1)

- Mathematics Year 6: Sekolah Kebangsaan BakapDocument1 pageMathematics Year 6: Sekolah Kebangsaan BakapAhmad HafizanNo ratings yet

- IctDocument20 pagesIctAhmad HafizanNo ratings yet

- PengurusanDocument22 pagesPengurusanAhmad HafizanNo ratings yet

- Let's Play English!Document1 pageLet's Play English!Nicoleta DănilăNo ratings yet

- Eduardo Talaman Thesis Title Final Portrait 1Document13 pagesEduardo Talaman Thesis Title Final Portrait 1al alNo ratings yet

- Fillable-AAF 014Document2 pagesFillable-AAF 014JEULO D. MADRIAGANo ratings yet

- General Training IELTS Writing Task 1 - Greetings and Salutation - Jeffrey-IELTS BlogDocument4 pagesGeneral Training IELTS Writing Task 1 - Greetings and Salutation - Jeffrey-IELTS Blogkunta_kNo ratings yet

- Prospectus of Law 2019-20Document51 pagesProspectus of Law 2019-20SanreetiNo ratings yet

- Instructional Planning - Educational PsychologyDocument14 pagesInstructional Planning - Educational PsychologyDesales BuerNo ratings yet

- Immersion #1Document3 pagesImmersion #1joy conteNo ratings yet

- ANVESHAN 2023 FormDocument4 pagesANVESHAN 2023 FormVikrant KumarNo ratings yet

- Secondary School Records Form 3Document1 pageSecondary School Records Form 3yasmeenabelallyNo ratings yet

- KS2 - 2000 - Mathematics - Test B - Part 2Document11 pagesKS2 - 2000 - Mathematics - Test B - Part 2henry_g84No ratings yet

- Julia Sehmer Verdun Lesson 1Document3 pagesJulia Sehmer Verdun Lesson 1api-312825343No ratings yet

- Authentic PedagogyDocument3 pagesAuthentic PedagogyOladimeji mariamNo ratings yet

- TS247 DT de Tham Khao Thi Tot Nghiep THPT Mon Anh Bo GD DT Nam 2021 Co Video Chua 75716 1623572154Document18 pagesTS247 DT de Tham Khao Thi Tot Nghiep THPT Mon Anh Bo GD DT Nam 2021 Co Video Chua 75716 1623572154Ngan GiangNo ratings yet

- Fix 2Document11 pagesFix 2lutfiyatunNo ratings yet

- E10tim106 PDFDocument64 pagesE10tim106 PDFhemacrcNo ratings yet

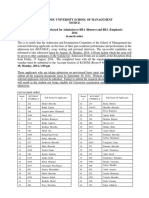

- Final List For BBA (Hons and Emphasis) KUSOM 2014Document3 pagesFinal List For BBA (Hons and Emphasis) KUSOM 2014education.comNo ratings yet

- ManualDocument25 pagesManualShailendra RamsahaNo ratings yet

- Central University of South Bihar Department of Political StudiesDocument2 pagesCentral University of South Bihar Department of Political StudiesNishant RajNo ratings yet

- Names NarrativeDocument23 pagesNames NarrativeJanine A. EscanillaNo ratings yet