Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Research

Uploaded by

jinny1_00 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views6 pagesarticle

Original Title

217

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentarticle

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views6 pagesResearch

Uploaded by

jinny1_0article

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

A randomised controlled trial of clinical

outreach education to rationalise antibiotic

prescribing for acute dental pain in the primary

care setting

J. M. Seager,

1

R. S. Howell-Jones,

2

F. D. Dunstan,

3

M. A. O. Lewis,

4

S. Richmond

5

and D. W. Thomas

6

Objective To assess the effect of educational outreach visits on

antibiotic prescribing for acute dental pain in primary care.

Study design Randomised controlled trial (RCT).

Setting General dental practices in four health authority areas in Wales.

Subjects and methods General dental practitioners were recruited

to the study and randomly allocated to one of the three study groups

(control group, guideline group or intervention group). Following the

intervention, practitioners completed a standardised questionnaire for

each patient that presented with acute dental pain.

Interventions The control group received no intervention. The guideline

group received educational material by post. The intervention group

received educational material by post and an academic detailing visit

by a trained pharmacist. The educational material included evidence-

based guidelines on prescribing for acute dental pain and patient

information leaflets.

Main outcome measures The number of antibiotic prescriptions issued

to patients presenting with dental pain and the number of inappropriate

antibiotic prescriptions. Antibiotics were considered to be inappropriate

if the patient did not have symptoms indicative of spreading infection.

Results A total of 1,497 completed questionnaires were received from

23, 20 and 27 general dental practitioners in the control, guideline

and intervention group respectively. Patients in the intervention group

received significantly fewer antibiotic prescriptions than patients in the

control group (OR (95% CI) 0.63 (0.41, 0.95)) and significantly fewer

inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions (OR (95% CI) 0.33 (0.21, 0.54)).

However, antibiotic and inappropriate antibiotic prescribing were not

1

Research Fellow, Department of Oral Surgery, Medicine and Pathology,

2*

Research

Assistant, Department of Oral Surgery, Medicine and Pathology,

3

Professor of Medical

Statistics, Department of Epidemiology, Statistics and Public Health,

4

Professor of

Oral Medicine, Department of Oral Surgery, Medicine and Pathology,

5

Professor of

Orthodontics, Department of Dental Health and Biological Sciences

6

Professor of Oral

Surgery, Department of Oral Surgery, Medicine and Pathology, Dental School, Wales

College of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, CF14 4XY

*Correspondence to: Miss Howell-Jones

Email: howell-jonesrs@cf.ac.uk

Refereed paper

Accepted 10 November 2005

DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4813879

British Dental Journal 2006; 201: 217222

significantly different in the guideline group compared to the

control group (OR (95% CI) 0.83 (0.55, 1.21) and OR (95% CI) 0.82

(0.53, 1.29) respectively).

Conclusions Strategies based upon educational outreach visits

may be successfully employed to rationalise antibiotic prescribing by

dental practitioners.

BACKGROUND

The management of acute dental pain is primarily based upon

an operative intervention, such as placement of a restoration,

extraction of a tooth or extirpation of the dental pulp. Despite

the general acceptance that antibiotic therapy is inappropriate as

a primary treatment of pain associated with inflammation of the

dental pulp,

1

antibiotics are frequently prescribed for this condi-

tion: a study of 1,069 patients in Cheshire attending emergency

dental clinics found 74% of patients with pulpitis were issued

with an antibiotic prescription without any surgical interven-

tion.

2

Furthermore, a previous study undertaken in Cardiff

demonstrated that 12% of 500 consecutive patients attending

a hospital emergency dental clinic were taking antibiotics at

the time of presentation.

3

Moreover, 57% of these patients had

received antibiotics in the absence of an appropriate clinical

indication. In addition to the over-prescription of antibiotics for

acute dental conditions, it has also been demonstrated that there

are wide variations in the type of antibiotic, frequency, dose and

duration of the therapy prescribed.

3-5

Inappropriate antibiotic usage, in addition to being an unneces-

sary cost, exposes the patients to the risk of adverse effects and may

contribute to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant organisms in the

community. It is, therefore, imperative that strategies are developed

to improve antibiotic prescribing for acute dental conditions in the

primary care setting by general dental practitioners (GDPs).

A Cochrane review has been published that examined the

impact of printed educational material on the quality and cost-

effectiveness of prescribing and concluded that the distribution

of educational material alone appears to have little effect on pre-

scribing behaviour.

6

However, other studies suggest that the distri-

bution of educational material followed by outreach visits using

a trained person (academic detailer) to meet face-to-face with the

I N BRI EF

Previous studies have shown that educational outreach visits (academic detailing) can reduce

inappropriate prescribing by medical practitioners.

This study sought to assess whether academic detailing combined with printed educational

material could be used to reduce antibiotic prescribing by dentists for acute dental pain.

Evidence based guidelines for the use of antibiotics and analgesics for acute dental pain were

produced.

Antibiotic prescribing by general dental practitioners for acute dental pain can be reduced

using academic detailing combined with guidelines. Guidelines alone do not affect antibiotic

prescribing.

RESEARCH

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 201 NO. 4 AUG 26 2006 217

VERIFIABLE

CPD PAPER

4p217-222.indd 217 16/8/06 14:39:54

health professional can be effective.

7,8

The role of the academic

detailer is to reinforce the educational material and emphasise

alternatives to the prescription of a particular drug or group of

drugs.

9-11

This type of intervention is often referred to as academic

detailing and examples of its previous use include interventions

to reduce use of benzodiazepines,

12

inappropriate antibiotics,

13-15

and non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,

16,17

and to improve

antidepressant prescribing in the elderly.

18

Patient expectation is an often cited explanation for the over-

prescription of antibiotics in medical practice.

19,20

Antibiotic use,

however, is only one of the reasons for patient attendance; symp-

tomatic relief and an explanation of the disease process are equally

important.

21

Intervention strategies, via educational material, tar-

geted at patients using primary care services have been shown to

reduce inappropriate prescribing.

7,22

The aim of this study was to rationalise unnecessary and inap-

propriate antibiotic prescribing for dental conditions in the pri-

mary care setting. A randomised controlled trial was undertaken to

test the effectiveness of interventions involving academic detail-

ing visits and patient-mediated educational material, in changing

prescribing habits for acute dental conditions. The objectives of

this project were to determine a rationale for antibiotic prescribing

for acute dental conditions, inform GDPs and patients regarding

appropriate prescribing habits and to assess the change in pre-

scribing habits as a result of active patient-mediated and practi-

tioner-mediated programmes.

METHODS

Study design and setting

The study was a randomised controlled trial involving primary

care GDPs in four health authority areas in Wales (Bro Taf,

Iechyd Morganwg, Dyfed Powys and Gwent). One practitioner

from each practice that provided services under the NHS was

initially eligible to participate. However, prior to randomisa-

tion, practitioners volunteering to participate who were also

registered as working at another practice from which a GDP

had already enrolled in the study, were excluded. This exclusion

was undertaken to reduce the risk of cross-group contamination.

Figure 1 shows the recruitment and flow of practitioners through

the study. Practices were stratified prior to randomisation by

their previous level of antibiotic prescribing (data from Health

Solutions Wales) and Health Authority. Stratified randomisa-

tion was then undertaken in the Department of Epidemiology,

Statistics and Public Health, Wales College of Medicine (using a

computer program developed in-house) and practices assigned to

one of three groups: control group, guideline group and inter-

vention group. Practitioners in the intervention group received

printed educational material by post and an academic detailing

visit, practitioners in the guideline group received educational

material by post with no academic detailing visit and the control

group received no intervention. Ethical approval for the study

was obtained from MREC for Wales and the respective Local

Research Ethics Committees.

The educational package

The educational package consisted of guidelines for the manage-

ment of acute dental pain, a laminated page summary of the rec-

ommendations and patient information leaflets. The primary aim

of the guidelines was to reduce the inappropriate prescribing of

antibiotic therapy. However, the guidelines also included recom-

mendations for the prescribing of analgesics and information on

emergency dental services in each local health authority.

The guidelines were developed in consultation with five GDPs

and three general medical practitioners. Medline, EmBase, DARE,

the National Research Register, the Oxford Pain Relief Database

and the Cochrane library were searched for systematic reviews,

randomised controlled trials and other relevant papers to ensure

the guidelines were as evidence-based as possible. This was sup-

plemented by a review of the bibliographies of recent reviews and

backed up by the expert knowledge of a consultant oral microbiol-

ogist. The guidelines were reviewed by an external consultant in

oral microbiology and by the Regional Pharmaceutical Advisors

and Directors of Dental Public Health in the four health authorities

involved in the study.

An information leaflet was designed for patients with acute

dental pain that provided details of dental services (including

emergency services in the relevant health authority) and pain

relief. Most importantly, the leaflet also explained that antibiotics

are not usually required for such a condition. The readability of

the leaflet was assessed using the Gunning Fog Index test and the

Fog reading score found to be nine years. The leaflet was reviewed

by external referees, as described above for the guidelines, as well

as by the Health Promotion Division in the National Assembly for

Wales and eight lay people. The lay people were recruited from the

Cardiff Dental Hospital Examination and Emergency Clinic wait-

ing room and their views elicited using two focus group discus-

sions facilitated by an experienced moderator. Clinicians and lay

people involved in the development phase of the study did not par-

ticipate in any other part of the main study.

Intervention

The educational package was posted to practitioners in the

guideline group and the intervention group. Each practitioner

in the intervention group was then visited by the academic

detailer (a pharmacist who had been closely involved with the

development of the guidelines) to discuss the content of the

guidelines and encourage the rational use of antibiotics and

analgesics when managing acute dental pain. The academic

detailer was trained in interpersonal skills and selling tech-

niques by a consultant experienced in training pharmaceutical

company representatives. This enabled the promotion of the

guidelines to be tailored according to the particular attitudes of

each practitioner. The academic detailer was blind to the level

of antibiotic prescribing (high, medium or low) of the practices

being visited.

Data collection

The effect of the intervention was evaluated using a dental pain

questionnaire which practitioners were asked to complete every

time an adult (aged over 16 years) presented with acute dental

pain. Information relating to the age, gender and registration

status of the patient, presenting complaint, findings on examina-

tion, dental treatment and advice given, antibiotics or analgesics

prescribed or recommended was collected. The questionnaire was

piloted in Cardiff Hospital Examination and Emergency Clinic.

Practitioners in the guideline and intervention groups were asked

to complete the questionnaires after receipt of the guidelines and

academic detailing visit respectively.

In order to assess whether patients who had not received an

antibiotic were as satisfied with their treatment as patients who

had received an antibiotic, a patient satisfaction questionnaire

was developed to use as a CATI (Computer Assisted Telephone

Interview). Practitioners were required to obtain each patients

consent before returning the dental pain questionnaire with the

patients telephone number. It was hoped that 10% of patients

would be systematically sampled throughout the study period

and contacted. However, many practitioners reported that obtain-

ing patient consent was time consuming and as a result, the rate

of return of questionnaires was slow. This part of the study was

therefore discontinued after contacting 156 consecutive patients.

Patients were excluded if they could not be contacted within two

weeks of their visit.

RESEARCH

218 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 201 NO. 4 AUG 26 2006

4p217-222.indd 218 16/8/06 14:40:57

RESULTS

Initially, 97 GDPs agreed to take part in the study, however,

following randomisation, 27 practitioners dropped out (Fig. 1).

Completed questionnaires were received from 23, 20 and 27

practitioners in the control, guideline and intervention group

respectively. The characteristics of the dental practitioners who

returned questionnaires, shown in Table 1, were found to be very

similar in the different arms of the study.

In total, 1,584 questionnaires were received from GDPs, of

which 87 had to be excluded as patients were under 16 years of

age. Therefore 1,497 questionnaires were analysed: 490, 451 and

556 questionnaires from the control, guideline and intervention

groups respectively. The characteristics of the patients are shown

in Table 1. The age and gender of patients were evenly distributed

between the groups but there were significantly more private reg-

istered patients in the intervention group than in the control and

guideline group (Chi-square test, P < 0.001).

Presenting complaint and findings on examination are shown

in Table 2. There were significantly more patients with a symptom

indicative of spreading infection (facial swelling, lymphadenopa-

thy, limited mouth opening, raised temperature, difficulty swallow-

ing or ANUG) in the intervention group than in the control group

(24.5% vs. 19%, Chi-square test, P = 0.03). The intervention group

and the guideline group, however, did not differ significantly (24.5

vs. 23.1%, Chi-square test, P = 0.60). The number of patients with a

symptom indicative of spreading infection decreased significantly

with age (Chi-square test, P < 0.05). The proportions of patients who

received dental treatment were 79.4%, 85.1% and 86.2% in control,

guideline and intervention group respectively, while the propor-

tions of patients who received advice in the control, guideline and

intervention groups were 76.5%, 71.8% and 75.5% respectively.

Data analysis

The main outcome measures analysed were the number of anti-

biotic prescriptions issued for patients presenting with acute

dental pain and the number of inappropriate antibiotic prescrip-

tions. Antibiotics were considered to be inappropriate if the

patient did not have facial swelling, lymphadenopathy, limited

mouth opening, raised temperature, difficulty swallowing or

acute necrotising ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG).

The data collected from the study were entered and analysed

in SPSS, while more advanced multilevel modelling was carried

out in MLWiN. Direct comparisons were made between the con-

trol, guideline and intervention groups using the Chi-square test,

one-way ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis test but the main analysis, to

assess the effect of the intervention on prescribing and to iden-

tify other factors which may influence prescribing, was carried

out using multilevel logistic regression to allow for within-

practice clustering. P values of <0.05 were considered to be

statistically significant.

Sample size

Practice, not practitioner, was the unit of randomisation and the

sampling was, therefore, a form of cluster sampling. The intra-

class correlation co-efficient was considered in the sample size

calculation since correlation between different patients from

the same practice inflates the required sample size. The intra-

class correlation coefficient was estimated from baseline data

to be 0.04. The study hoped to recruit 30 GDPs into each arm

of the study and to obtain data on 30 patients from each GDP.

This sample size was chosen to have 90% power for detecting a

change of one third in the prescribing rate of antibiotics, from

28% to 18%.

Guideline only group

(n=32)

Stratified randomisation

of practices (N=97)

Academic outreach

group (n=33)

Control Group

(n=32)

Guidelines received

(n=32)

Academic outreach

visit (n=29)

No intervention

(n=32)

GDPs returned

questionnaires

(n=20)

GDPs returned

questionnaires

(n=27)

GDPs returned

questionnaires

(n=23)

GDPs agreeing to

participate (n=111)

Invited GDPs (N=343)

451 questionnaires 556 questionnaires 490 questionnaires

No questionnaires

returned (n=2)

No visit (n=4)

No questionnaires

returned (n=12)

No questionnaires

returned (n=9)

The number of

questionnaires returned

by participating GDPs

No. ques. No. GDPs

>25 12

20-24 1

15-19 4

10-14 0

5-9 3

<5 3

The number of

questionnaires returned

by participating GDPs

No. ques. No. GDPs

>25 12

20-24 0

15-19 0

10-14 3

5-9 2

<5 3

The number of

questionnaires returned

by participating GDPs

No. ques. No. GDPs

>25 13

20-24 3

15-19 5

10-14 2

5-9 3

<5 1

Excluded from study (n=14)

1. Connected with another

practice in study (n=6)

2. Connected with development

of guidelines (n=4)

3. Stratification not possible due

to lack of prescribing data (n=4)

Explicit decline to participate (n=127)

Non response (n=216)

Fig. 1 Flowchart of GDP participation and study design

Table 1 Characteristics of GDPs (who returned questionnaires) and

patients

Arm of study

Control Guideline Intervention

Number of GDPs 23 20 27

Gender

Male (%) 65 75 81

Female (%) 35 25 18.1

Mean years since qualification

19.4

(SD 10)

21.2

(SD 8.2)

22.1

(SD 8.6)

Mean pop:wte in the LHB of

each practice

3724

(SD 735)

3927

(SD 818)

3938

(SD 924)

Number (%) of dentists with

post graduate qualifications

3 (13.0) 1 (5.0) 4 (14.8)

Number of patients 490 451 556

Mean age (years)

44.3

(SD 16.9)

43.7

(SD 16.2)

45.7

(SD 16.2)

Gender

Male (%) 45 42 44

Female (%) 55 58 56

Registration

Status

NHS (%) 75 70 65

Private (%) 8 8 20*

Not registered

(%)

16 20 15

Not specified

(%)

1 2 0

Pop:wte Ratio of mean population to whole-time equivalent dentists

LHB Local Health Board

*Significantly more privately registered patients in the intervention group than in the control

and guideline group (Chi-square-test, P < 0.001).

RESEARCH

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 201 NO. 4 AUG 26 2006 219

4p217-222.indd 219 17/8/06 16:36:21

In the analysis of antibiotic prescriptions there were two out-

come measures: 1) all antibiotic prescriptions and 2) inappropriate

antibiotic prescriptions. Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing was

defined as the provision of an antibiotic to a patient who did not

present with a symptom indicative of spreading infection. For all

antibiotics, and also for inappropriate antibiotics, the differences

between the groups were substantial. However, considerable vari-

ation occurred between practitioners within the three groups and,

therefore, multilevel modelling was used to reflect the hierarchical

data, with patients clustered within practitioners. Taking clustering

into account, a 95% confidence interval for the difference between

the intervention and control groups was (0.3%, 17%) for all antibi-

otic prescriptions while that for the difference between the guide-

line and control groups was (-6.4%, 12.4%). The odds ratios (OR),

comparing the chance of a patient being prescribed an antibiotic

and an inappropriate antibiotic in the separate study groups are

shown in Table 3. They were estimated using multilevel logistic

regression and show the chance of a prescription in the interven-

tion group to be significantly lower than the control group.

The influence of both patient and practitioner characteristics on

the tendency to prescribe was explored using multivariate multi-

level analysis. Patient characteristics were age, gender and regis-

tration status, while the practitioner characteristics were gender,

a postgraduate qualification, number of years since qualification

and the population to whole-time equivalent dentists ratio (pop:

wte) in the LHB of the dental practice. Table 4 shows the OR of an

antibiotic prescription associated with different levels of each fac-

tor. The individual factors were included in a model one at a time

in addition to the main factor of the study group.

The only factor other than the group that was statistically sig-

nificant was age; younger patients were significantly more likely

to receive antibiotics than older patients. Other factors showed

interesting trends but these were not statistically significant. The

variables for which the evidence of an association was weakest,

namely the genders of patient and dentist, the years since quali-

fication and the pop:wte levels, were left out of the model. The

resulting model parameters were as shown in Table 5. Inappropri-

ate prescribing was also modelled using multivariate multilevel

logistic regression. In this analysis, none of the patient or practi-

tioner factors, other than study group, was found to be significant,

including patients age.

Table 2 Presenting complaints and findings on examination by patients

(%) presenting at GDPs with acute dental pain

Control

group

n = 490 (%)

Guideline

group

n = 451 (%)

Intervention

group

n = 556 (%)

Presenting complaint

Toothache 327 (66.7) 315 (69.8) 377 (67.8)

Painful/infected gums 129 (26.3) 107 (23.7) 122 (21.9)

Fractured filling 34 (6.9) 29 (6.4) 26 (4.7)

Lost filling 40 (8.2) 25 (5.5) 21 (3.8)

Broken filling 72 (14.7) 70 (15.5) 44 (7.9)

Facial swelling 53 (10.8) 65 (14.4) 79 (14.2)

Other 5 (1.0) 1 (0.2) 4 (0.8)

Extraoral examination

Normal 388 (79.2) 328 (72.7) 412 (74.1)

Swelling 71 (14.5) 90 (20.0) 112 (20.1)

Lymphadenopathy 54 (11.0) 47 (10.4) 71 (12.8)

Limited mouth opening 25 (5.1) 29 (6.4) 39 (7.0)

Raised temperature 11 (2.2) 13 (2.9) 11 (2.0)

Difficulty swallowing 10 (2.0) 12 (2.7) 6 (1.1)

Other 2 (0.4) 4 (0.9) 1 (0.2)

Intraoral examination

Caries 135 (27.6) 163 (36.1) 134 (24.1)

Lost/broken fillings 110 (22.4) 75 (16.6) 74 (13.3)

Tender teeth 171 (34.9) 169 (37.5) 170 (30.6)

Loose teeth 64 (13.1) 81 (18.0) 66 (11.9)

Recent fractured tooth 58 (11.8) 40 (8.9) 34 (6.1)

Abscess/pus discharge 94 (19.2) 115 (25.5) 113 (20.3)

Gingival inflammation 118 (24.1) 98 (21.7) 106 (19.1)

ANUG 7 (1.4) 3 (0.7) 5 (0.9)

Other 2 (0.4) 4 (0.9) 10 (1.9)

Percentage of patients

with a symptom of

spreading infection

19.0% 23.1% 24.5%

Table 3 Antibiotic prescribing

Patients prescribed

antibiotics

Patients prescribed

antibiotics inappropriately

% OR (95% CI) % OR (95% CI)

Control group

(n = 490)

32 1 18 1

Guideline group

(n = 451)

29 0.83 (0.55, 1.21) 15 0.82 (0.53, 1.29)

Intervention group

(n = 556)

23 0.63 (0.41, 0.95) 7 0.33 (0.21, 0.54)

Table 4 Influence of study group, patient and practitioner characteristics

on antibiotic prescribing, explored using multivariate multilevel analysis.

Factor Unit of comparison Odds ratio (95% CI) P-value

Prescribing

Intervention vs. control

Guideline vs. control

0.59 (0.57, 0.93)

0.81 (0.50, 1.30)

0.022

0.40

Age of

patient

Difference of 10 years 0.82 (0.76, 0.89) <0.0001

Gender of

patient

Female vs. male 1.07 (0.84, 1.36) 0.58

Type of

registration

Private vs. NHS

Unregistered vs. NHS

1.41 (0.90, 2.20)

0.89 (0.62, 1.26)

0.13

0.50

Gender of

GDP

Female vs. male 1.02 (0.63, 1.61) 0.93

Postgraduate

qualification

Qualification vs. none 0.51 (0.26, 1.01) 0.05

Years since

qualification

of GDP

<15 against 16-30

<15 against 30

1.16 (0.73, 1.81)

1.36 (0.76, 2.41)

0.53

0.29

Pop: wte in

LHB

*

Medium vs. small

Large vs. small

1.23 (0.77, 1.93)

1.36 (0.84, 2.17)

0.37

0.21

Pop:wte Ratio of mean population to whole-time equivalent dentists

LHB Local Health Board

* The values of the pop:wte were divided into 3 categories, up to 2500, 2501-4000, and

more than 4000.

RESEARCH

220 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 201 NO. 4 AUG 26 2006

4p217-222.indd 220 16/8/06 14:44:13

The types of antibiotics prescribed are shown in Figure 2 and

the duration of antibiotic treatment summarised in Table 6. The

differences between the durations were not significant (Kruskal

Wallis test, P > 0.05).

Patient satisfaction survey

A total of 156 patients were contacted, 89 of whom were from

the control group and 67 from the guideline group. Twenty-nine

of the patients in the control group and 16 in the guideline group

had received a prescription for an antibiotic. Approximately 40%

of patients (36 from the control group and 25 from the guideline

group) stated that they thought their dental problem was caused

by an infection. However, only 23% of patients expected to get a

prescription for an antibiotic, and only 26% of patients hoped for

a prescription. Gender did not influence whether a patient hoped

for an antibiotic prescription (Chi-square test, P > 0.05), how-

ever, there was a significant difference in the mean age of those

patients that hoped for an antibiotic prescription (40.5 years) and

those that did not (49.8 years), (t-test, P < 0.05). The majority of

patients who had hoped for an antibiotic prescription did receive

one: only six patients hoped for a prescription for an antibiotic

but did not receive one but nine patients who did not want a pre-

scription did receive one. Of those patients that did not receive an

antibiotic, only three patients (all in the control group) answered

that they were dissatisfied with the dentists decision. In addition,

there was no evidence that patients who had not received a pre-

scription for an antibiotic were less likely to feel that the treatment

they had received had been effective, compared with patients who

had received an antibiotic (Chi-square test, P > 0.05).

Analgesic prescriptions or recommendations

Analgesic prescribing was found to be significantly higher

in the guideline (22.8% of patients) and intervention (20.3%

of patients) groups than the control group (2.7% of patients).

However, the difference between the guideline group and the

intervention group was not significant.

Antibiotics were used more frequently than analgesics by den-

tists in all three study groups. Patients prescribed antibiotics were

not significantly more likely to be prescribed an analgesic in any

of the study groups (OR (95% CI) for control group 1.85 (0.61,

5.60), guideline group 0.95 (0.58, 1.54) and intervention group

1.56 (0.98, 2.54)). Furthermore, fitting a multilevel model showed

no significant interaction between study group and analgesic on

antibiotic prescribing.

Ibuprofen was prescribed, or recommended, more than any

other analgesic in all three study groups, with paracetamol being

the second most frequently used analgesic. However, practitioners

in the intervention group prescribed or recommended paracetamol

significantly less than practitioners in the other two groups (Chi-

squared test, P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Several studies have demonstrated that educational outreach

visits can significantly affect prescribing, including antibi-

otic prescribing, by general medical practitioners.

12-14,16,17,23,24

However, this is the first study, to our knowledge, to assess the

effect of educational outreach visits on prescribing by GDPs. A

significant reduction in the number of antibiotic prescriptions

issued by dentists in the intervention group compared to dentists

in the control and guideline groups was obtained following edu-

cational outreach visits by a pharmacist. The chance that dentists

in the intervention group would write an antibiotic prescription

for patients presenting with acute dental pain was approximately

70% that of dentists in the control group.

Factors such as patient gender and registration status were

not found to significantly influence prescribing and neither did

practitioner characteristics such as gender, number of years since

qualification and ratio of the mean population to whole time

equivalent dentist (pop:wte) in the local health board. The only

factor that significantly influenced prescribing other than study

group was age; younger patients were more likely to receive anti-

biotics than older patients. However, this could be because older

patients were less likely to present with a symptom of spreading

infection (facial swelling, lymphadenopathy, limited mouth open-

ing, raised temperature, difficulty swallowing or ANUG) than

younger patients. Indeed, there was also a significant reduction

in the level of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions in the inter-

vention group compared to the control group, and here the age of

the patient did not significantly affect inappropriate prescribing.

The chance that dentists in the intervention group would write an

inappropriate antibiotic prescription for acute dental pain was a

third that of dentists in the control group.

20

10

0

30

40

50

60

*

*

+

*

+

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

a

n

t

i

b

i

o

t

i

c

s

Amoxicillin Erythromycinn Penicillin Metronidazole Other

antibiotic

Two

antibiotics

Control group

Guideline group

Intervention group

Fig. 2 The percentage of each antibiotic type prescribed by GDPs.

*Significantly different from the control group (Chi-square test, P < 0.05);

+

Significantly different from the guideline group (Chi-square test, P < 0.05)

Table 5 Influence of study group, patient and practitioner characteristics

on antibiotic prescribing, by multivariate multilevel analysis when the

variables for which the evidence of an association was weakest (the

genders of patient and dentist, the years since qualification and the pop:

wte levels) were left out of the model.

Factor Unit of comparison

Odds ratio

(95% CI)

P-value

Prescribing

Intervention vs. control

Guideline vs. control

0.62 (0.40, 0.97)

0.83 (0.55, 1.35)

0.033

0.47

Age of patient Difference of 10 years 0.82 (0.76, 0.89) <0.0001

Type of

registration

Private vs. NHS

Unregistered vs. NHS

1.41 (0.91, 2.21)

0.89 (0.62, 1.26)

0.12

0.50

Postgraduate

qualification

Qualification vs. none 0.58 (0.31, 1.01) 0.10

Pop:wte Ratio of mean population to whole-time equivalent

Table 6 Duration of antibiotic treatment

Control group

n (%)

Guideline group

n (%)

Intervention

group n (%)

Less than 3 days 2 (1) 3 (2) 5 (4)

3 or 4 days 32 (20) 13 (10) 27 (21)

5 days 109 (69) 96 (73) 77 (59)

More than 5 days 12 (9) 19 (15) 21 (16)

RESEARCH

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 201 NO. 4 AUG 26 2006 221

4p217-222.indd 221 17/8/06 16:37:23

Analgesic prescribing was very low in all three groups and den-

tists were more likely to use an antibiotic than an analgesic. Many

practitioners in the intervention group commented that dental pain

is considerably reduced following dental treatment and they feel

that analgesics are no longer required. It is not clear why analgesic

prescribing was so much lower in the control group compared to

the other two groups. Practitioners in the guideline and interven-

tion groups used the non steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, ibu-

profen, more often than any other analgesic, as recommended in

the guidelines. Several studies have shown that non steroidal anti-

inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen, are more effective than

paracetamol for relieving dental pain.

25,26

Questionnaires were used to assess prescribing in order to col-

lect diagnosis related data and to distinguish between antibiotics

prescribed for the management of acute dental pain and antibiotics

prescribed for prophylaxis. The fact that practitioners had to com-

plete a questionnaire each time they saw a patient with acute dental

pain might have focused the attention of practitioners in all three

groups and thus reduced their prescribing. However, this would

have reduced the possibilities of detecting prescribing differences

in the study. Furthermore, information on antibiotic prescribing

was not specifically requested and practitioners were not told that

the study was about antibiotic prescribing. Details of all prescrip-

tions were solicited and the guidelines included recommendations

for analgesic prescribing as well as antibiotic prescribing.

The number of questionnaires returned in this study was lower

than the a priori calculated sample size. The decreased numbers

will have reduced the power of the study to identify any differ-

ences between the groups and will have led to wider confidence

intervals for any effect sizes. However, the main comparison was

statistically significant and the likely effect of a larger sample

would have been to increase the precision with which the effect

size was estimated. It is possible that some of the differences in the

secondary outcomes may have been significant with the planned

sample size but the main objective was achieved.

Medical practitioners perception of patient expectation with

regard to issuing antibiotic prescriptions, as well as patients

hopes, has been shown to be a strong determinant in the decision

to prescribe.

20

In this study, a small number of patients who had

attended a general dental practitioner were surveyed to ascer-

tain whether there was a high level of expectation for receiving

an antibiotic. Only about one-quarter of patients said they hoped

to receive a prescription for antibiotics. Furthermore, only 3% of

those patients who did not receive an antibiotic were dissatisfied

with the dentists decision.

CONCLUSION

The results from this randomised controlled trial suggest that

evidence based guidelines alone do not improve prescribing

by general dental practitioners. However, educational outreach

visits by a pharmacist may be successfully employed to improve

prescribing.

Future research

Studies need to be undertaken that address the durability of

behaviour change following academic detailing, and assess

methods for reinforcing guidelines and maintaining changes in

clinical practice. Studies should also be undertaken to evaluate

the impact of reductions in antibiotic prescribing by general

dental and general medical practitioners on costs, outcomes and

antibiotic resistance in the community.

This study was funded in full by a grant from the NHS National R&D Programme

on Primary Dental Care.

1. Olson A K, Edington E M, Kulid J C, Weller R N. Update on antibiotics for the

endodontic practice. Compendium 1990; 11: 328-332.

2. Dailey Y M, Martin M V. Are antibiotics being used appropriately for emergency

dental treatment? Br Dent J 2001; 191: 391-393.

3. Thomas D W, Satterthwaite J, Absi E G et al. Antibiotic prescription for acute dental

conditions in the primary care setting. Br Dent J 1996; 181: 401-404.

4. Palmer N, Martin M. An investigation of antibiotic prescribing by general dental

practitioners: a pilot study. Prim Dent Care 1998; 5: 11-14.

5. Roy K M, Bagg J. Antibiotic prescribing by general dental practitioners in the Greater

Glasgow Health Board, Scotland. Br Dent J 2000; 188: 674-676.

6. Freemantle N, Harvey E L, Wolf F et al. Printed educational materials. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2004; 2.

7. Gill P S, Makela M, Vermeulen K M et al. Changing doctor prescribing behaviour.

Pharm World Sci 1999; 21: 158-167.

8. Thomson OBrien M A, Oxman A D, Davis D A et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on

professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000: 2.

9. Soumerai S B, Avorn J. Principles of educational outreach (academic detailing) to

improve clinical decision making. JAMA 1990; 263: 549-556.

10. Bernal-Delgado E, Galeote-Mayor M, Pradas-Arnal F, Peiro-Moreno S. Evidence

based educational outreach visits: effects on prescriptions of non-steroidal anti-

inflammatory drugs. J Epidemiol Comm Health 2002; 56: 653-658.

11. Freemantle N, Nazareth I, Eccles M et al. A randomised controlled trial of the effect

of educational outreach by community pharmacists on prescribing in UK general

practice. Br J Gen Pract 2002; 52: 290-295.

12. Berings D, Blondeel L, Habraken H. The effect of industry-independent drug

information on the prescribing of benzodiazepines in general practice. Eur J Clin

Pharmacol 1994; 46: 501-505.

13. Avorn J, Soumerai S B. Improving drug-therapy decisions through educational

outreach. A randomized controlled trial of academically based detailing. N Engl

J Med 1983; 308: 1427-1463.

14. Santoso B, Suryawati S, Prawaitasari J E. Small group intervention vs formal seminar

for improving appropriate drug use. Soc Sci Med 1996; 42: 1163-1168.

15. Ilett K F, Johnson S, Greenhill G et al. Modification of general practitioner prescribing

of antibiotics by use of a therapeutics advisor (academic detailer). Br J Clin Pharmacol

2000; 49: 168-173.

16. Stergachis A, Fors M, Wagner E H et al. Effect of clinical pharmacists on drug

prescribing in a primary-care clinic. Am J Hosp Pharm 1987; 44: 525-529.

17. Newton-Syms F A, Dawson P H, Cooke J et al. The influence of an academic

representative on prescribing by general practitioners. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1992;

33: 69-73.

18. van Eijk M E C, Avorn J, Porsius A J, de Boer A. Reducing prescribing of highly

anticholinergic antidepressants for elderly people: randomised trial of group versus

individual academic detailing. Br Med J 2001; 322: 1-6.

19. Britten N. Patients demands for prescriptions in primary care. Patients cannot take

all the blame for overprescribing. Br Med J 1995; 310: 1084-1085.

20. Britten N, Ukoumunne O. The influence of patients hopes of receiving a prescription

on doctors perceptions and the decision to prescribe: a questionnaire survey. Br Med

J 1997; 315: 1506-1510.

21. Hamm R M, Hicks R J, Bemben D A. Antibiotics and respiratory infections: are patients

more satisfied when expectations are met? J Fam Pract 1996; 43: 56-62.

22. Davis D A, Thomson M A, Oxman A D, Haynes R B. Changing physician performance.

A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA

1995; 274: 700-705.

23. McConnell T S, Cushing A H, Bankhurst A D et al. Physician behaviour modification

using claims data: tetracycline for upper respiratory infection. West J Med 1982;

137: 448-450.

24. Coenen S, Van Royen P, Michiels B, Denekens J. Optimizing antibiotic prescribing for

acute cough in general practice: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Antimicrob

Chemother 2004; 54: 661-672.

25. Cooper S A, Schachtel B P, Goldman E et al. Ibuprofen and acetaminophen in

the relief of acute pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

J Clin Pharmacol 1989; 29: 1026-1030.

26. Barden J, Edwards J E, McQuay H J et al. Relative efficacy of oral analgesics after third

molar extraction. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 407-411.

RESEARCH

222 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 201 NO. 4 AUG 26 2006

4p217-222.indd 222 16/8/06 14:46:40

You might also like

- Curry PowderDocument8 pagesCurry PowderMahendar Vanam100% (1)

- Assertmodule 1Document9 pagesAssertmodule 1Olivera Mihajlovic TzanetouNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of Impression Technique For ConventionalDocument7 pagesA Systematic Review of Impression Technique For ConventionalAmar BhochhibhoyaNo ratings yet

- Afpam47 103v1Document593 pagesAfpam47 103v1warmil100% (1)

- Stress Fatigue PrinciplesDocument12 pagesStress Fatigue Principlesjinny1_0No ratings yet

- Dental Anxiety QuestionnairesDocument4 pagesDental Anxiety QuestionnairesAmar BhochhibhoyaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal AntibiotikDocument5 pagesJurnal AntibiotikSela PutrianaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Systematic Oral Care in Critically Ill PatientsDocument7 pagesEffects of Systematic Oral Care in Critically Ill PatientsCarlene AlincastreNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument11 pagesIntroductionshrikantNo ratings yet

- Schwartz 2007Document8 pagesSchwartz 2007adriana Ortega CastilloNo ratings yet

- Advancing Infection Control in Dental Care SettingDocument12 pagesAdvancing Infection Control in Dental Care SettingEndang SetiowatiNo ratings yet

- Evidence Based Practise of Oral MedicineDocument10 pagesEvidence Based Practise of Oral MedicineshrikantNo ratings yet

- 10.1007/s00520 013 1942 0 PDFDocument13 pages10.1007/s00520 013 1942 0 PDFhendra ardiantoNo ratings yet

- Prescribing Trends of Systemic Antibiotics by Periodontists in AustraliaDocument27 pagesPrescribing Trends of Systemic Antibiotics by Periodontists in AustraliaMohammad HarrisNo ratings yet

- Clinical Efficacy of Local Delivered Minocycline in The Treatment of Chronic Periodontitis Smoker PatientsDocument5 pagesClinical Efficacy of Local Delivered Minocycline in The Treatment of Chronic Periodontitis Smoker PatientsvivigaitanNo ratings yet

- General Practitioner Antimicrobial Stewardship Programme Study (GAPS) : Protocol For A Cluster Randomised Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesGeneral Practitioner Antimicrobial Stewardship Programme Study (GAPS) : Protocol For A Cluster Randomised Controlled TrialAlexandrahautaNo ratings yet

- A Study of Prescription Pattern of Antibiotics in Pediatric In-Patients of Mc-Gann Teaching Hospital Shivamogga Institute of Medical Sciences (SIMS), Shivamogga, Karnataka.Document5 pagesA Study of Prescription Pattern of Antibiotics in Pediatric In-Patients of Mc-Gann Teaching Hospital Shivamogga Institute of Medical Sciences (SIMS), Shivamogga, Karnataka.International Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Swoope1977 PDFDocument8 pagesSwoope1977 PDFKrupali JainNo ratings yet

- Oral Care Practice For The Ventilated Patients in Intensive Care Units: A Pilot SurveyDocument7 pagesOral Care Practice For The Ventilated Patients in Intensive Care Units: A Pilot SurveyRochman MujayantoNo ratings yet

- Di Susun Untuk Memenuhi Tugas Mata Kuliah Mikrobiologi Dan ParasitologiDocument5 pagesDi Susun Untuk Memenuhi Tugas Mata Kuliah Mikrobiologi Dan ParasitologiJulfianas Bekti WahyuniNo ratings yet

- Study DesignsDocument36 pagesStudy Designsz6f9cw8vwvNo ratings yet

- Venugopalan2016 PDFDocument7 pagesVenugopalan2016 PDFSyahidatul Kautsar NajibNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of Malnutrition in Hospitals Can Be Reduced: Results From Three Consecutive Cross-Sectional StudiesDocument11 pagesThe Prevalence of Malnutrition in Hospitals Can Be Reduced: Results From Three Consecutive Cross-Sectional StudiesManlio Fabio FelixNo ratings yet

- Ab Round StewardshipDocument7 pagesAb Round StewardshipbpinsaniNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Basedprosthodontics: Fundamental Considerations, Limitations, and GuidelinesDocument17 pagesEvidence-Basedprosthodontics: Fundamental Considerations, Limitations, and GuidelinesRohan BhagatNo ratings yet

- Bell 2012Document13 pagesBell 2012badria bawazirNo ratings yet

- Oral Care in Ventilation MechanicDocument8 pagesOral Care in Ventilation MechanicRusida LiyaniNo ratings yet

- Patient Perceptions of The Role of Nutrition For Pressure Ulcer Prevention in HospitalDocument7 pagesPatient Perceptions of The Role of Nutrition For Pressure Ulcer Prevention in HospitalSher UmarNo ratings yet

- Contents DCLDocument3 pagesContents DCLpopy ApriliaNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Prescribing and Resistance:: Views From Low-And Middle-Income Prescribing and Dispensing ProfessionalsDocument42 pagesAntibiotic Prescribing and Resistance:: Views From Low-And Middle-Income Prescribing and Dispensing ProfessionalsFaozan FikriNo ratings yet

- Evid Based Nurs 2000 Treatment 75Document2 pagesEvid Based Nurs 2000 Treatment 75Dyana Fitri EningsihNo ratings yet

- 18factores Asociados Al Llamado Por Tto Oncologico Monestime Page 2020Document8 pages18factores Asociados Al Llamado Por Tto Oncologico Monestime Page 2020Milizeth VmNo ratings yet

- Knowledgeartyku PDFDocument9 pagesKnowledgeartyku PDFAhmed Abdulleh Al Hada'aNo ratings yet

- EBM of DyspepsiaDocument228 pagesEBM of DyspepsiaxcalibursysNo ratings yet

- Epic3 National Evidence-Based Guidelines For Preventing HCAI in NHSEDocument70 pagesEpic3 National Evidence-Based Guidelines For Preventing HCAI in NHSECarmen VarodiNo ratings yet

- ADA Adult Acute Dental Pain Guideline 2023Document25 pagesADA Adult Acute Dental Pain Guideline 2023Elaf AlBoloshiNo ratings yet

- Validity Two Methods For Assessing Oral Health Status of PopulationsDocument9 pagesValidity Two Methods For Assessing Oral Health Status of PopulationsSyarifah HaizanNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Dosage Prescribed in Oral Implant Surgery: A Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional SurveysDocument16 pagesAntibiotic Dosage Prescribed in Oral Implant Surgery: A Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional SurveysShounak GhoshNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices and Status of Oral Health Among Diabetic Patients at Kikuyu HospitalDocument2 pagesKnowledge, Attitudes, Practices and Status of Oral Health Among Diabetic Patients at Kikuyu HospitalNthie UnguNo ratings yet

- Williams Et Al-2019-Cochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsDocument4 pagesWilliams Et Al-2019-Cochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsErlinda AlfaNo ratings yet

- Emergency Dental Treatment Among Patients Waitlisted For The Operating RoomDocument5 pagesEmergency Dental Treatment Among Patients Waitlisted For The Operating RoomnatalyaNo ratings yet

- 17Document7 pages17bie2xNo ratings yet

- Compliance With Universal Precautions in A Medical Practice With A High Rate of HIV InfectionDocument6 pagesCompliance With Universal Precautions in A Medical Practice With A High Rate of HIV InfectionDirga Rasyidin LNo ratings yet

- Artigo - Compliance Oral Nutrition Supplement - ReviewDocument20 pagesArtigo - Compliance Oral Nutrition Supplement - ReviewFrancielle A.RNo ratings yet

- The Need For Pharmaceutical Care in An Intensive Care Unit at A Teaching Hospital in South AfricaDocument4 pagesThe Need For Pharmaceutical Care in An Intensive Care Unit at A Teaching Hospital in South AfricaAdibaNo ratings yet

- G AntibiotictherapyDocument3 pagesG AntibiotictherapyJavangula Tripura PavitraNo ratings yet

- Gibson 2010Document19 pagesGibson 2010fiora.ladesvitaNo ratings yet

- 0300060517740813Document13 pages0300060517740813Putu Ayu Krisna Sutrisni21No ratings yet

- The Use of Fibre OpticcarioDocument3 pagesThe Use of Fibre OpticcarioNelly AndriescuNo ratings yet

- Determinants Impacting The Use of Antibiotics Among Patients Visiting The Dental Clinic at Kampala International University Teaching Hospital in Bushenyi-Ishaka Municipality, WesteDocument15 pagesDeterminants Impacting The Use of Antibiotics Among Patients Visiting The Dental Clinic at Kampala International University Teaching Hospital in Bushenyi-Ishaka Municipality, WesteKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Angela M Berry 2011Document6 pagesAngela M Berry 2011M Farid AzNo ratings yet

- DyspepsiaDocument228 pagesDyspepsiaamal.fathullah100% (1)

- Editorials: Evidence Based Medicine: What It Is and What It Isn'tDocument4 pagesEditorials: Evidence Based Medicine: What It Is and What It Isn'tDanymilosOroNo ratings yet

- JIndianSocPedodPrevDent344348-3624096 100400Document6 pagesJIndianSocPedodPrevDent344348-3624096 100400drkameshNo ratings yet

- How Decisions Are Made Antibiotic Stewardship in DentistryDocument6 pagesHow Decisions Are Made Antibiotic Stewardship in DentistryMuhammad SdiqNo ratings yet

- Corresponding Author: Mojtaba Vaismoradi, Faculty of Professional Studies, Nord UniversityDocument24 pagesCorresponding Author: Mojtaba Vaismoradi, Faculty of Professional Studies, Nord UniversityTeddy Kurniady ThaherNo ratings yet

- JP Journals 10024 2084Document8 pagesJP Journals 10024 2084darwinNo ratings yet

- 747-Article Text-1365-1-10-20200430Document6 pages747-Article Text-1365-1-10-20200430Yogita DhurandharNo ratings yet

- Infection Control & Hospital EpidemiologyDocument9 pagesInfection Control & Hospital EpidemiologyRianNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument7 pagesResearch ArticleMohammed Falih HassanNo ratings yet

- The Timeliness of Patients Reporting The Side Effects of ChemotherapyDocument8 pagesThe Timeliness of Patients Reporting The Side Effects of ChemotherapyChristine SiburianNo ratings yet

- New Oral Care With ClorhedineDocument10 pagesNew Oral Care With ClorhedineZil FadilahNo ratings yet

- Advances in Managing Fistulizing Crohn’s Disease: A Multidisciplinary ApproachFrom EverandAdvances in Managing Fistulizing Crohn’s Disease: A Multidisciplinary ApproachNo ratings yet

- Groper's ApplianceDocument4 pagesGroper's Appliancejinny1_0No ratings yet

- E Adaproceedings-Child AbuseDocument64 pagesE Adaproceedings-Child Abusejinny1_0No ratings yet

- AAPD Policy On - FluorideUseDocument2 pagesAAPD Policy On - FluorideUsejinny1_0No ratings yet

- GicDocument5 pagesGicmrnitin82No ratings yet

- G - TMD-pedo MNGMT PDFDocument6 pagesG - TMD-pedo MNGMT PDFjinny1_0No ratings yet

- Pulp Therapy-Guideline AapdDocument8 pagesPulp Therapy-Guideline Aapdjinny1_0No ratings yet

- EEL 7 SpeakingDocument20 pagesEEL 7 SpeakingSathish KumarNo ratings yet

- Mucosa in Complete DenturesDocument4 pagesMucosa in Complete Denturesspu123No ratings yet

- Article-PDF-Amit Kalra Manish Kinra Rafey Fahim-25Document5 pagesArticle-PDF-Amit Kalra Manish Kinra Rafey Fahim-25jinny1_0No ratings yet

- Spacer Design Jips 2005 PDFDocument5 pagesSpacer Design Jips 2005 PDFjinny1_0No ratings yet

- GoldsDocument11 pagesGoldsjinny1_0No ratings yet

- DisinfectionDocument5 pagesDisinfectionjinny1_0No ratings yet

- KurthDocument18 pagesKurthjinny1_0No ratings yet

- Die HardnerDocument4 pagesDie Hardnerjinny1_0No ratings yet

- ResinDocument8 pagesResinjinny1_0No ratings yet

- Denture Base Resin CytotoxityDocument7 pagesDenture Base Resin Cytotoxityjinny1_0No ratings yet

- Oral Mucosal Lesions Associated With The Wearing of Removable DenturesDocument17 pagesOral Mucosal Lesions Associated With The Wearing of Removable DenturesnybabyNo ratings yet

- Implant AngulationDocument17 pagesImplant Angulationjinny1_0No ratings yet

- 7Document8 pages7jinny1_0No ratings yet

- Patient-Assessed Security Changes When Replacing Mandibular Complete DenturesDocument7 pagesPatient-Assessed Security Changes When Replacing Mandibular Complete Denturesjinny1_0No ratings yet

- 3Document7 pages3jinny1_0No ratings yet

- Avg Vs NormalDocument1 pageAvg Vs Normaljinny1_0No ratings yet

- AlginateDocument5 pagesAlginatejinny1_0No ratings yet

- 11Document7 pages11jinny1_0No ratings yet

- Long-Term Cytotoxicity of Dental Casting AlloysDocument8 pagesLong-Term Cytotoxicity of Dental Casting Alloysjinny1_0No ratings yet

- Kalitantra-Shava Sadhana - WikipediaDocument5 pagesKalitantra-Shava Sadhana - WikipediaGiano BellonaNo ratings yet

- ELS 15 Maret 2022 REVDocument14 pagesELS 15 Maret 2022 REVhelto perdanaNo ratings yet

- PresentationDocument6 pagesPresentationVruchali ThakareNo ratings yet

- Proposal For A Working Procedure To Accurately Exchange Existing and New Calculated Protection Settings Between A TSO and Consulting CompaniesDocument9 pagesProposal For A Working Procedure To Accurately Exchange Existing and New Calculated Protection Settings Between A TSO and Consulting CompaniesanonymNo ratings yet

- EVS (Yuva)Document88 pagesEVS (Yuva)dasbaldev73No ratings yet

- Project 2 Analysis of Florida WaterDocument8 pagesProject 2 Analysis of Florida WaterBeau Beauchamp100% (1)

- Competent Testing Requirements As Per Factory ActDocument3 pagesCompetent Testing Requirements As Per Factory Actamit_lunia100% (1)

- Mat101 w12 Hw6 SolutionsDocument8 pagesMat101 w12 Hw6 SolutionsKonark PatelNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Global Marketing Management 6th Edition Masaaki Mike Kotabe Kristiaan HelsenDocument34 pagesTest Bank For Global Marketing Management 6th Edition Masaaki Mike Kotabe Kristiaan Helsenfraught.oppugnerp922o100% (43)

- New Horizon Public School, Airoli: Grade X: English: Poem: The Ball Poem (FF)Document42 pagesNew Horizon Public School, Airoli: Grade X: English: Poem: The Ball Poem (FF)stan.isgod99No ratings yet

- Review Test 1: Circle The Correct Answers. / 5Document4 pagesReview Test 1: Circle The Correct Answers. / 5XeniaNo ratings yet

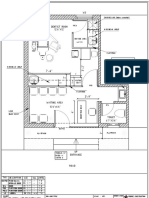

- Dental Clinic - Floor Plan R3-2Document1 pageDental Clinic - Floor Plan R3-2kanagarajodisha100% (1)

- M 995Document43 pagesM 995Hossam AliNo ratings yet

- Design of Ka-Band Low Noise Amplifier Using CMOS TechnologyDocument6 pagesDesign of Ka-Band Low Noise Amplifier Using CMOS TechnologyEditor IJRITCCNo ratings yet

- Manual ML 1675 PDFDocument70 pagesManual ML 1675 PDFSergio de BedoutNo ratings yet

- 3.1.1 - Nirmaan Annual Report 2018 19Document66 pages3.1.1 - Nirmaan Annual Report 2018 19Nikhil GampaNo ratings yet

- Recent Advances in Dielectric-Resonator Antenna TechnologyDocument14 pagesRecent Advances in Dielectric-Resonator Antenna Technologymarceloassilva7992No ratings yet

- Hamza Akbar: 0308-8616996 House No#531A-5 O/S Dehli Gate MultanDocument3 pagesHamza Akbar: 0308-8616996 House No#531A-5 O/S Dehli Gate MultanTalalNo ratings yet

- Alliance For ProgressDocument19 pagesAlliance For ProgressDorian EusseNo ratings yet

- MGN815: Business Models: Ajay ChandelDocument38 pagesMGN815: Business Models: Ajay ChandelSam RehmanNo ratings yet

- LADP HPDocument11 pagesLADP HPrupeshsoodNo ratings yet

- Alexander Fraser TytlerDocument4 pagesAlexander Fraser Tytlersbr9guyNo ratings yet

- Mywizard For AIOps - Virtual Agent (ChatBOT)Document27 pagesMywizard For AIOps - Virtual Agent (ChatBOT)Darío Aguirre SánchezNo ratings yet

- Encephalopathies: Zerlyn T. Leonardo, M.D., FPCP, FPNADocument50 pagesEncephalopathies: Zerlyn T. Leonardo, M.D., FPCP, FPNAJanellee DarucaNo ratings yet

- Vishakha BroadbandDocument6 pagesVishakha Broadbandvishakha sonawaneNo ratings yet

- Paper 11-ICOSubmittedDocument10 pagesPaper 11-ICOSubmittedNhat Tan MaiNo ratings yet

- The Life Cycle of Brent FieldDocument21 pagesThe Life Cycle of Brent FieldMalayan AjumovicNo ratings yet

- Annual Report 2022 2Document48 pagesAnnual Report 2022 2Dejan ReljinNo ratings yet

- Kaibigan, Kabarkada, Kaeskwela: Pinoy Friendships and School LifeDocument47 pagesKaibigan, Kabarkada, Kaeskwela: Pinoy Friendships and School LifeGerald M. LlanesNo ratings yet