Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2001 Ginger Thesis

Uploaded by

naveengargnsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

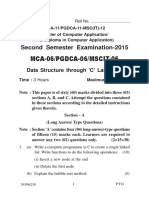

2001 Ginger Thesis

Uploaded by

naveengargnsCopyright:

Available Formats

Introduction

This paper has gone through so many permutations that it is nearly unrecognizable

from its original form. I began with the intent to compare Buddhist and Christian

liberation theology, a project born from my eperiences at a progressi!e "esuit high

school and a semester of Buddhist studies in #athmandu, $epal. %!entually I narrowed

my topic to the application of Buddhist and Christian liberation theologies in &sia. I

decided to focus on the wor' of a theologian named &loysius (ieris, a )ri *an'an "esuit

who attempts to combine Catholicism and Thera!adin Buddhism into a new social

message for &sia+s poor. &s of spring ,---, my plan was to use a ./0 grant to spend

the summer reading the wor's of (ieris and other theologians and then tra!el to India in

the fall with the &ntioch College Buddhist )tudies (rogram. I 'new that the &ntioch

program allows a month for independent study and tra!el, and loo'ed forward to !isiting

(ieris in )ri *an'a.

1uring the course of the summer, howe!er, the political situation in )ri *an'a

rapidly deteriorated, and I realized that proper compassion for my mother necessitated a

change of topic. I began to read boo's and articles by theologians who referred to

themsel!es as 1alit Christians, and through them I disco!ered &mbed'ar and the 1alit

Buddhists. I e!entually tra!eled to India, but instead of !isiting )ri *an'a I di!ided my

time for independent study between the Buddhists in Bombay and the Christians in

Bangalore, a center for Indian Christian acti!ity.

The month spent inter!iewing and reading about 1alit Buddhists and 1alit

Christians was perhaps the most stimulating academic eperience of my life, and it

2

spar'ed a near obsession with 1r. &mbed'ar and the social mo!ements that ha!e

de!eloped because of him. 3ere I use the term academic in the broadest possible sense,

for the power of this eperience lay in the fact that it prompted both intellectual and

personal reflection. 4or eample, I will ne!er forget the end of my inter!iew with

)amuel, a 1alit Christian and 5arist in Bangalore. 3e loo'ed at me and my friend and

said, )o, what are you going to do with this6 I began to eplain that I was wor'ing on

my honors thesis, the final project of my college career, but he soon cut me off. $o, he

said, I mean what are you going to do with this6 I can only hope that my inade7uate

response was subse7uently gi!en !alue by public and pri!ate eploration of what it

means to ta'e part in religious studies. )imilarly, before I tra!eled to Bombay my

education had barely touched upon the caste system, Indian politics, 1r. &mbed'ar, and

the 5ahars. 8hen I returned home, ready to wor' on my honors thesis, at !ery the least I

understood how much more there was for me to learn.

&s is clear from this paper+s title, I ha!e narrowed my focus further and dropped the

subject of 1alit Christians. This decision was dictated by time constraints only9

untouchables present an interesting challenge to the growing ecumenism of the Catholic

church and I hope one day to continue studying the de!elopments that are occurring in

)outhern India. 5y paper also lac's an in:depth analysis of the politics of untouchability,

a subject I began to learn about while writing a research paper on untouchable human

rights and Indian law. There will ne!er be enough time to include e!erything, but I

would li'e to say that &mbed'ar has influenced me most by illustrating the etent to

which religion and politics ha!e mutual influence on each other.

,

There are numerous people I+d li'e to than' for helping me with this project. *inda

3ess has shared my enthusiasm for &mbed'ar and has in turn shared of herself

immeasurably. Bob ;regg, and 5ar' 5ancall ha!e had tremendous impact on my

thin'ing and my )tanford eperience in general. (eter 4riedlander and %llen (osman

were my two guides from &ntioch, and I would not ha!e learned nearly so much from my

time in Bombay if I had not been able to compare notes with Tom, #aren, and Bec'y. It

is not an understatement to say that I was o!erwhelmed by the 'indness of the people I

inter!iewed in India. & few indi!iduals stand out< 1r. Borhale, 4r. 4ran'ie, and )amuel.

*astly, I want my parents to 'now that I appreciate the support and freedom they+!e

gi!en me=than' you for letting me tra!el so far and for being so fun to come home to.

>

Chapter 1

Purpose, Context, and Terminology

This paper eplores the relationship between &mbed'ar, Buddhism, and the 5ahars

?&mbed'ar+s subcaste, or jati@. It constitutes one method of eamining the process of

collecti!e redefinition that the 5ahars ha!e engaged in as a result of their con!ersion to

Buddhism. I begin with a brief o!er!iew of the untouchable situation and an eplanation

of my choice in terminology and subject. The second chapter then eplores the lin'ages

between &mbed'ar+s biography and the political history of the 5ahars. It places

&mbed'ar+s life within the contet of Indian politics and history and argues that his

interest in religious con!ersion was a product of that contet. The third chapter outlines

&mbed'ar+s !iews on religion and his conscious reconstruction of Buddhism as an ideal

religion for the 5ahars. The fourth chapter eamines the ways that contemporary

5ahars ha!e li!ed out &mbed'ar+s Buddhist message, and the fifth synthesizes

&mbed'ar+s theory with current 5ahar practice to create a typology of the 1alit

Buddhist myth. Throughout, I emphasize the political and religious continuities

between &mbed'ar+s eperience, the 5ahar+s eperience, and the form of Buddhism that

has resulted from the two. I conclude by drawing on contemporary 1alit *iterature to

summarize the 5ahars+ relationship to &mbed'ar.

0!er!iew of .ntouchability

The practice of untouchability in rooted in both the religion and culture of India.

&ncient 3indu tets such as the Aedas, pro!ide insight into how Brahman priests

B

concei!ed the caste system during the second millenium BC% ?4lood >C@. They describe

four main castes ?or varnas@ which loosely correspond to the occupations of priest,

warriorDruler, merchant, and laborer. There is little mention of untouchables, a fifth and

lowest group technically outside the system. The correctly order the uni!erse, ha!ing

been present since the creation of human beings. These groups are !iewed descending

order of 'armic worth and are determined by birth. .ntouchables, howe!er, are largely

ecluded from the 3indu epics, although %'ala!ya in the Mahabarata and )hambu'a in

the Ramayana are notable eceptions. Both tell the story of shoc'ing atrocities that are

committed against otherwise praiseworthy indi!iduals, thus gi!ing testimony to the

precariousness of untouchables+ place in ancient culture. The Manu Smriti, dated between

the second century BC% and the third century C%, argues that interactions between castes

should be go!erned by comple laws of ritual pollution ?4lood EC@. This tet condemns

untouchables to a life of segregation and degradation, lin'ed closely to the fact that they

perform polluting tas's such as disposing of human and cow carcasses. It states, Their

dress shall be the garments of the dead, they shall eat their food from bro'en dishes,

blac' iron shall be their ornaments, and they must always wander from place to place.

Their food shall be gi!en to them by others in a bro'en dish9 at night they shall not wal'

about in towns and !illages ?B2B:B2E@. 8hether or not the Manu Smriti describes the

situation of untouchables with historical accuracy, it is clear that Brahmanic 3induism

regarded untouchables as an anathema to the caste system.

5uch as Indian culture is often indistinguishable from 3indu culture, the caste

system and untouchability are integrated into nearly e!ery facet of Indian life. The

historical origins of caste are unclear, although some hypothesize that it stemmed from

E

racial differences between the &ryans, who are said to ha!e migrated to India from the

$orthwest, and the dar'er indigenous Indians ?the )ans'rit word for caste is varna, which

means color@ ?5endelsohn and Aicziany F@. Today, howe!er, e!en /oman Catholics in

southern India seat themsel!es according to caste during mass and follow principles of

ritual pollution in!ol!ing physical touch and food ?inter!iew, 4r. 4ran'ie@.

Contemporary anthropological theory of untouchability centers on the debate

between continuity and discontinuity with respect to untouchables and greater Indian

culture ?1eliege >-@. *ouis 1umont+s Homo Hierarchicus pro!ides the standard eample

of the former, which emphasizes the interdependence of all the groups in the caste system

?1eliege >G@. Both Brahmans and untouchables are ultimately dependent on each other

to maintain the dichotomy between ritual purity and impurity ?1eliege >G@. Thus the

caste system creates a unified, though stratified, culture. 3owe!er, a number of scholars

ha!e attempted to refute 1umont+s assertions, in general arguing against the

comprehensi!eness of the caste system as a form of societal go!ernance. They conclude

that untouchables do not subscribe to the !alues imposed on them by caste and that their

relationship to Indian society is characterized by systematic eclusion ?1eliege B>@.

*astly, some scholars, such as 1eliege, ha!e de!eloped the con!incing argument that

untouchables are both needed and ecluded by the caste system. &s 1eliege writes,

.ntouchables are indeed an integral part of Indian society, as their essential economic

and ritual roles show9 but they are, also and at the same time, ecluded from this society,

and their marginal position is constantly underscored through !arious taboos and

discriminations ?CF@.

C

8hate!er the origin and function of caste may be, it is clear that contemporary

untouchables suffer from a sense of shame that is associated with their low social and

ritual status. (. 5ohan *arbeer, an 1alit Christian, writes, 8hen I was doing my

se!enth standard, I came to 'now that I belonged to an untouchable communityHI felt

!ery lowly and embarrassed and I tried to hide myself inside a shell, acutely aware and

conscious of my caste, and a!oided discussing it ?>FE@. *arbeer+s use of the words

lowly and embarrassed highlights the etent to which many untouchables ha!e

de!eloped what of my informants referred to as a damaged psyche ?4r. 4ran'ie,

22DFD-2@. 1eliege+s sur!ey of untouchability, published in 2GGE, confirms that *arbeer+s

eperience can be generalized< 8hate!er their social position and merit, .ntouchables

are ashamed of their social bac'ground and try to conceal it whene!er possible. To be

forced publicly to ac'nowledge one+s caste is humiliating and insulting ?2E@. Before

they can mobilize to claim their fundamental human rights, untouchables must

themsel!es that they deser!e those rights in the first place. *i'e *arbeer, many

untouchables try to hide themsel!es in a shell because they lac' any sense of self:worth

that would allow them to be proacti!e about gaining social e7uality. Thus any

untouchable attempts to change Indian society must be accompanied by an alternati!e

way of defining the self.

The )tin'ing $ame

&mbed'ar writes, .nfortunately, names ser!e a !ery important purpose. They

play a great part in social economy. $ames are symbols. %ach name represents

association of certain ideas and notions about a certain object. It is a labelHThe name

F

.ntouchable is a bad name. It repels, forbids, and stin's ?&way from the 3indus,

B2G@. ;i!en the importance that &mbed'ar and his followers ha!e assigned to they

names they use to refer to themsel!es, I would li'e to eplain my choices in terminology.

There are currently se!eral words used to describe the group of indi!iduals referred to as

I)cheduled CastesI by the Indian go!ernment< harijan, e:untouchable, untouchable, and

dalit. Harijan is a name first proposed by 5.#. ;andhi, translating into %nglish as

children of ;od. It was chosen as an epression of all Indians+ e7uality under god, and

implies that untouchables deser!e access to the 3indu religious practices pre!iously

denied them. 3owe!er, many untouchables argue that the term is paternalistic and

condescending and, gi!en ;andhi+s own attitude towards untouchables, there seems to be

some merit to their criti7ue. This ma'es harijan an undesirable choice for academic

writing.

8hereas harijan is supposed to connote patient and pious suffering, the term e:

untouchable draws attention to the fact that all practices of untouchability were formally

outlawed in 2GE-, by &rticle 2F of the Indian Constitution. &s the rather aw'ward

terminology of the Indian Census and other legal documents suggest, technically there

are no untouchables in India today. 3owe!er, to use the term e:untouchable ignores the

fact that &rticle 2F was followed by the .ntouchability ?0ffenses@ &ct of 2GEE, the

creation of the (rotection for Ci!il /ights Cell in 2GF>, the )cheduled Castes and

)cheduled Tribes ?(re!ention of &trocities@ &ct of 2GJG, and the )cheduled Castes and

)cheduled Tribes ?(re!ention of &trocities@ /ules of 2GGE. In short, although the

Constitution declared untouchability illegal, it merely represents the first in a long series

of legal palliati!es that ha!e had little if any effect on the situation of untouchables. The

J

punishable acts listed by the (re!ention of &trocities /ules, which include forcing

someone to drin' or eat inedible or noious substances, forcing someone to beg or

become a bonded laborer, and murder, death, massacre, rape, mass rape, and gang rape,

permanent incapacitation and dacoity, gi!e ade7uate testimony to the fact that

untouchability has been remo!ed from India in name only ?&trocities /ules 2GGE@. &s

/obert 1eliege points out, referring to untouchables as e:untouchables disregards the

defining characteristics of their contemporary eperience ?2J@.

The term dalit has been chosen by untouchables to specifically emphasize

eperiences that ha!e often been ignored by the rest of Indian society. It is a 5arathi

word that means ground, bro'en or reduced to pieces generally, although some

contemporary 1alit Christians argue that it is also found in 3ebrew and )ans'rit ?Kelliot

,CF and 5assey 2@. By selecting the word dalit, untouchables self:consciously chose to

redefine themsel!es in terms of their social and psychological oppression. <hough dalit

is the word most !ocally supported by untouchables, it has certain political connotations.

It is associated specifically with the 1alit (anthers, more generally with 1alit Buddhists,

and has yet to gain wide acceptance beyond the 5ahar community. )e!eral scholars use

dalit because it is the only term resulting from the acti!e agency of untouchables, but I

ha!e hesitated to follow in their footsteps because it has only recently gained prominence

beyond &mbed'ar+s community ?1eliege 2C@. 1escribing all untouchables as dalits

implies a self:awareness of their situation that not all untouchables ha!e. It also might

imply that I support both &mbed'ar+s ideology and the political !iews of his followers.

This may be the case, but hope to achie!e academic impartiality in this writing and then

G

find other, more appropriate, !enues for con!incing others of the worthiness of

&mbed'ar+s cause.

Thus I use the term untouchable throughout the present paper ?2J@. 4ew Indians

use the term9 it is the property mainly of scholars and outside obser!ers ?1eliege 2F@. I

do, howe!er, use the word dalit when referring to members of the Dalit sahitya

mo!ement, as their community has clearly come to consensus about using the term. &s I

am both a student and a foreigner to Indian culture, my choice gi!es !oice to a distance

that already eisted between my subject and me. 3owe!er, it is etremely important to

note that this is not the word that 5ahars use to refer to themsel!es ?They would use

dalit, 1alit Buddhist, $eo:Buddhist, 5ahar, or &mbed'arite.@

I also ma'e a distinction between Buddhism, &mbed'ar+s Buddhism, and

1alit Buddhism. I use Buddhism only in reference to the teachings of the Buddha as

the Thera!ada, 5ahayana, or Aajrayana !ehicles traditionally understand them.

&mbed'ar+s Buddhism, on the other hand, refers to the specific reinterpretation of 1r.

B./. &mbed'ar. &s we will see, the differences between &mbed'ar+s Buddhism and

traditional Buddhism are great enough=at least according to contemporary definitions of

Buddhism=to warrant a separate term for each. Let I will also argue that Buddhism as

practiced by the 5ahars differs greatly from Buddhism as presented by &mbed'ar, and

thus I create a third category of Buddhism. I refer to this set of beliefs and practices as

1alit Buddhism. <ernati!ely, I could ha!e used the terms $eo:Buddhism or

&mbed'arism, but I chose 1alit Buddhism for the sa'e of consistency.

8hy the 5ahars6

2-

This paper focuses only on the ways in which &mbed'ar+s Buddhism was designed

for and li!ed out by the 5ahar community. I chose this approach for se!eral reasons.

4irst, all of my own obser!ations are of 5ahar Buddhists in Bombay. )econd, there is

more anthropological and historical data a!ailable on 1alit Buddhism and the 5ahars

than there is for other untouchable communities. This is largely due to the efforts of

%leanor Kelliot, but other researchers such as Timothy 4itzgerald, $eera Burra, and

"ohannez Beltz ha!e also chosen to focus on Buddhism in 5aharashtra. Third, the

5ahars constitute a di!erse community that defies easily generalization, and ma'ing

additional conclusions about more than one sub:caste warrants a much longer paper than

the one I intended to write. 4ourth, and most importantly, Buddhism has the greatest

number of adherents in the 5ahar community ?FEM of 5ahars claim to be 1alit

Buddhist@ ?Kelliot 2,F@. This is due largely to the fact that &mbed'ar was a 5ahar, and

we shall see that there is a clear cultural lin' between the 5ahars, &mbed'ar+s ideology,

and his interpretation of Buddhism.

3owe!er, the reader should note that &mbed'ar+s Buddhism was not intended for

eclusi!e use by the 5ahars. 0n the contrary, it was concei!ed as a religion for all of

India+s untouchables and for oppressed people of the world in general. <hough there

are clear parallels between the 5ahars+ social and political needs and &mbed'ar+s

Buddhist message, it would be a mista'e to thin' that &mbed'ar intended to create a

race:based or culturally determined religion.

22

Chapter 2

Ambedkar in the Context of the Mahars and Indian istory

&mbed'ar as 5ahar< %arly *ife and %ducation

&mbed'ar was born as a 5ahar, a member of the largest untouchable sub:caste in

the state of 5aharashtra. %leanor Kelliot describes the 5ahar+s traditional occupation as

that of the !illage ser!ant or, balutedar, whose duties re!ol!ed around mundane aspects

of maintaining !illage order such as mending walls, acting as watchman, arbitrating in

boundary disputes, informing landowners of their duty to pay !illage dues, and sweeping

roads ?JF@. Those 5ahars not in!ol!ed in balutedar wor' generally relied on agriculture

as a means of support. &dditionally, 5ahars remo!ed the carcasses of dead cattle from

the !illage and regularly ate carrion beef, two practices that justified their untouchability

in the minds of the caste 3indu ?Kelliot JJ@. &s Kelliot writes, The 5ahar+s duties were

performed in the contet of his untouchability9 his touch was polluting and he did not

come into direct contact with a caste 3indu or enter a caste 3indu home. The temple, the

school, the !illage well were closed to him ?JJ@. 4or eample, one of &mbed'ar+s

contemporaries remembers that he was not allowed to share the community water well

and was punished if he touched other students in school ?Borhale 22:,B:--@. The aspect

of ritual pollution permeated e!ery aspect of the 5ahar+s relationship with their

surrounding culture, and they were generally belie!ed to be dirty, fre7uent consumers of

alcohol, and morally la ?Kelliot C-@. 0ne un'nown poet wrote, Their ?the 5ahar+s@

houses are outside the !illage9 there are lice in their women+s hair9 na'ed children play in

the rubbish9 they eat carrion ?Kelliot C-@. Thus Kelliot cites a traditional 5arathi

2,

pro!erb< 8here!er there is a !illage there is a maharwada ?the designated area outside

the !illage where the 5ahars li!ed@ ?JF@. In %nglish, this phrase would approimate to,

There+s a blac' sheep in e!ery floc', and it illustrates the way the 5ahars were

inetricably bound to and yet rejected by the communities they li!ed in ?Kelliot JF@.

3owe!er, significant shifts in the 5ahars+ social and occupational status had ta'en

place during the two generations preceding &mbed'ar+s birth. Kelliot writes, 8ith the

ad!ent of British rule, other opportunities for wor' were opened to the 5ahar, his

traditional role being such that he was both free and pressed to ta'e whate!er new

!ocation presented itself ?JJ@. These new !ocations often too' the form of wor' on the

doc's and in railways, roads, tetile mills, and go!ernment industries such as ammunition

factories ?Kelliot JG@. 5any of these jobs re7uired 5ahars to mo!e to cities such as

Bombay, (une, and $agpur, and as urbanized members of the community pushed

increasingly for education and changes in social status, their relati!es in !illages followed

suit and began to shed both the duties and social customs that had once been associated

with their untouchability ?Kelliot JG@. 5any 5ahars also joined the British army, which

pro!ided another means of escaping the constraints of traditional social hierarchies before

the British de!eloped their theory of martial races that ecluded the 5ahars ?Barbara

"oshi E-@. Zelliot carefully documents the ways in which 19

th

century Mahar social

movements, led by men such as Jotirao hule and !o"al #aba $alan%&ar 'see (Mahar

and )on*#rahman Movements in Maharashtra+,- )he characterizes the 5ahars as an

upwardly mobile social group who were eager to use recent changes in occupation as a

platform for increased social change. &ll of these factors suggest that the culture

surrounding &mbed'ar during his youth was characterized by increasing political

2>

awareness and social mobility. &fter passing through the crucible of 5orningside

3eights, &mbed'ar was able to return to India with both the confidence and the 'now:

how to effect radical political change for the 5ahars.

The basic facts of &mbed'ar+s early life epitomize this rapid de!elopment of 5ahar

social consciousness that was in opposition to cultural and religious degradation.

&mbed'ar was born in 2JG2 in a small !illage outside of (une. 3is father mo!ed the

family to Bombay because the !illage schools would not admit low:caste children

?$ritin%s and S"eeches, .ol- 1/, B@. 3owe!er, &mbed'ar continued to suffer from caste:

based prejudice e!en while attending school in this new urban center ?5oon B@.

&mbed'ar studied at the Bombay (residency )chool and then at %lphinstone College in

Bombay. The 5aharaja of Baroda, a liberal reformer who funded many students from

Bombay (residency, paid for the latter part of his college education. &fter &mbed'ar+s

graduation, the 5aharaja also sent him to Columbia .ni!ersity in $ew Lor'. &t

Columbia, &mbed'ar recei!ed a 5aster+s 1egree and a 1octorate of (hilosophy in

%conomics, )ociology and (olitical and 5oral (hilosophy ?5oon E and Kelliot 2EF@.

&mbed'ar+s stay at Columbia coincided with a period of great de!elopment in political

and social thought. 5en such as "ohn 1ewey and the anthropologist &leander

;oldenweiser were in the midst of formulating theories that would become the

cornerstone of &merican thin'ing, and &mbed'ar made an effort to study under as many

of these great minds as he could ?J-@. Kelliot refers to &mbed'ar+s study at Columbia as

an eposure to optimistic, epansi!e, pragmatic body of 'nowledge ?J-@. 3e then

tra!eled to *ondon and recei!ed a 1octorate of )cience from the *ondon )chool of

%conomics and entrance to the Bar from ;rey+s Inn ?Kelliot 2EF@. 8hen &mbed'ar

2B

finally returned to Bombay in 2G,>, he was among India+s minority of college:educated

men and its most highly educated untouchable. 3e was also one of only three men in

Indian public life to ha!e had an etended stay in the .nited )tates ?Kelliot FG@.

Let &mbed'ar+s education, though etraordinary, was not necessarily an anomaly in

the contet of greater changes that were ta'ing place in 5ahar society. 4or eample,

&mbed'ar+s initial mo!e to Bombay reflects the 5ahar+s increasing tendency of 5ahar

to migrate from rural to urban settings. In turn, his education in the .nited )tates ga!e

him first hand eperience of the daily life and political theory of a country that did not

ad!ocate religiously based social hierarchies. Thus, after passing through the crucible of

5orningside 3eights, &mbed'ar was able to return to India with both the confidence and

the 'now:how to effect radical political changes for untouchables.

5ahar as (olitician< &mbed'ar+s (olitical Career

;ail 0m!edt argues that &mbed'ar established his role as a leader of untouchables

in three ways< by submitting testimony to the )outhborough Committee on /eforms,

appearing at two major untouchable conferences in 2G,-, and founding a journal named

Moo&naya&, or the Aoice of the 5ute ?2BE@. 0f these, the testimony to the

)outhborough Committee is most significant because it introduces the idea of distinct

untouchable socio:cultural identity to Indian political theory ?0m!edt 2BC@. In what

0m!edt refers to as an elo7uent assertion of identity and claim to autonomy, &mbed'ar

argued that the protection of the rights of untouchables was contingent upon direct

representation of untouchables in legislatures. In his words<

The right of representation and the right to hold office under the state are the two most

important rights that ma'e up citizenship. But the untouchability of the untouchables puts

these rights far beyond their reach. In a few places they do not e!en possess such

2E

insignificant rights as personal liberty and personal security. These are the interests of the

untouchables. &nd as can be easily seen, they can be represented by untouchables alone

?0m!edt 2BC@.

0ne should note that this argument for political preference contradicts the assertion of

cultural unity that was made by high caste leaders of the untouchable mo!ement=many

of whom had not e!en wanted untouchables to be able to testify before the Committee

?0m!edt 2BE@. 3ere, as elsewhere, he phrases the untouchables+ problems in terms of

fundamental rights, personal liberty, indi!idual security, and the fulfillment of citizenship.

Thus he creates a clear connection between untouchability, which is arguably a religious

phenomenon, and the rights of citizenship, which are primarily political. This allows him

to propose that a legal system ?legislature@ can pro!ide solutions for the problems raised

by a religious system ?3induism@. In prose reflecting the democratic optimism that

characterized the political theory of his &merican contemporaries, &mbed'ar !oices his

belief that democracy should be gi!en priority o!er 3induism. This fusion of religion and

politics largely foreshadows the justification he ga!e for religious con!ersion in the

2G>-+s. &t the time, howe!er, &mbed'ar+s argument was noteworthy because it

highlighted the differences between the methodology of untouchables and the

methodology of outside leaders of untouchables.

&mbed'ar was further established as leader of the untouchable mo!ement at the

5ahad )atyagraha of 2G,F ?0m!edt 2E-@. 1uring a staged protest, 2E-- untouchables

dran' out of a water tan' that had been recently opened to them by an act of legislation.

In a speech that made se!eral parallels between the struggles of untouchables and the

4rench /e!olution, &mbed'ar told his followers, 8e are not going to the Cha!adar *a'e

merely to drin' its water. 8e are going to the *a'e to assert that we too are human

2C

beings li'e others. It must be clear that this meeting has been called to set up the norm of

e7ualityH0thers will not do it ?oisoned #read ,,E@. Let caste 3indus attac'ed the

protestors, riots ensued, and Brahman priests insisted on cleansing the polluted water

tan'. &mbed'ar then organized another rally around the right to drin' water, and here he

burned a copy of the Manusmriti in front of a crowd of 2-,--- untouchables. 5any

untouchables now refer to the initial mo!e to drin' common water as .ntouchable

Independence 1ay ?0m!edt 2E,@.

4ollowing the 5ahad )atyagraha, the untouchable mo!ement was increasingly

bound to the construction of Indian independence. Between 2G,G and 2G>, the British

initiated a series of /ound Table Conferences with the goal of pro!iding a format for

dialogue among Indians about the framing of their national constitution. The issue of

untouchable representation in legislature was raised repeatedly throughout these

conferences. 0nce again &mbed'ar, as one of two untouchable representati!es, stated

that the 1epressed Classes constituted a distinct part of the greater 3indu community. In

the wa'e of similar demands that had been granted to 5uslim and Christian minorities,

he asserted that untouchables should be gi!en separate !oting electorates and a number of

reser!ed seats in the legislature ?Kelliot 2>,@.

5.#. ;andhi was the most !ocal opponent of &mbed'ar+s plan, arguing against

both separate electorates and reser!ed seats in the legislature. ;andhi belie!ed that

constitutional support of a distinct untouchable culture would create an irreparable rift in

Indian society ?Kelliot 2>,@. ;andhi had two primary objections to &mbed'ar+s line of

reasoning. 4irst, in star' contrast to &mbed'ar, ;andhi belie!ed that law would ne!er be

able to sol!e the problem of untouchability ?"oshi BB@. 1ue to what Barbara "oshi refers

2F

to as a deep distrust of the coerci!e powers of the state, ;andhi pressed for change in

the hearts and the minds of people o!er structural modifications of the political system

?BB@. ;andhi belie!ed that lasting social change would occur only if caste 3indus

recognized the injustices of the caste system and then changed their actions accordingly.

The second ideological difference between ;andhi and &mbed'ar was that ;andhi

opposed untouchability but did not reject the caste system. &n article that he wrote for

0oun% 1ndia in 2G,C outlines his thin'ing<

In accepting the fourfold di!ision ?of caste@, I am simply accepting the laws of $ature,

ta'ing for granted what is inherent in human nature, and the law of heredity. 8e are born

with some of the traits of our parents. The fact that a human being is born only in the

human species shows that some characteristics, i. e. caste, is determined by birth. There is

scope enough for freedom of the will inasmuch as we can to a certain etent reform some

of our inherited characteristicsH& Brahmana may, by doing the deeds of a )hudra, become

a )hudra in this !ery birth, but the world loses nothing in continuing to treat him as a

Brahmana ?"oshi B>@.

In later years ;andhi also defended the concept of hereditary occupations but not the

prohibition of intermarriage and inter:caste dining ?"oshi B>@. 3e argued that once people

understood the !alue of all occupations they would gi!e e7ual respect to all members of

society, and thus the caste system would pro!ide di!ision of labor without !alue

judgement. Let two problems arise for untouchables if one accepts ;andhi+s arguments.

4irst, his !iew differs little from that of classical Brahmanism, which does not bode well

for his aim to change hearts and minds without radical the use of institutional reform.

)econd, the last part of his statement, the world loses nothing in continuing to treat him

?the errant Brahmin@ as a Brahmana, seems to promote apathy in the face of mo!ements

for structural social change. $ot only does ;andhi fail to eplain eactly how a Brahmin

would be treated under the proposed system, but also one wonders if he means to imply

that the world loses nothing by continuing to treat a )udra as a )udra. If this is the case,

2J

then the ;andhian !ision of India lea!es little=if any=opportunity for social mobility

on the part of the depressed classes.

The &mbed'ar:;andhi conflict embodies the conflict surrounding untouchable

leadership. Could untouchables rely on anyone other than another untouchable to

procure and maintain their fundamental rights6 Both &mbed'ar and ;andhi laid claim to

the same role. &mbed'ar clearly structured all of his political thin'ing around the

concept of untouchability, yet ;andhi told the 5inorities Committee in 2G>2, I claim

myself in my own person to represent the !ast mass of .ntouchables ?0m!edt 2F2@.

Kelliot writes of the /ound Table Conferences<

The conflict between the two men ?;andhi and &mbed'ar@ can be defined in se!eral

ways< &mbed'ar+s stress upon the ri%hts of the 1epressed Classes !ersus ;andhi+s stress

upon the duty of the caste 3indus to do penance9 &mbed'ar+s complete rejection of caste

!ersus ;andhi+s defense of chaturvarnaHas necessary to 3induism9 &mbed'ar+s rational

democratic liberalism !ersus ;andhi+s appeals to traditional modes of thought9 and the

ine!itable clash between the aggressi!e demands of a minority group leader and the

slower, broader:based and somewhat paternalistic etension of rights by the majority

group reformer ?2>>@.

0m!edt is less neutral in her assessment of the difference in leadership that the two men

presented. )he writes<

The point is that ;andhi, who feared a political di!isionHin the !illages, ignored the

di!ision that already eisted9 in his warning against the spread of !iolence, he ignored the

!iolence already eisting in the li!es of the 1alits. Claiming to spea' in the name of

untouchables, claiming to represent their cause and their !ital interests, ;andhi was

not spea'ing from their perspecti!e9 he was not e!en spea'ing as a national leader9 he

was spea'ing as a Hindu in his appearance at this )econd /ound Table conference ?2F,@.

;andhi and &mbed'ar thus presented two radically differing !iews on the best way to

alle!iate the problems facing untouchables9 the first is rooted in the caste 3indu

perspecti!e and the second in the eperiences and aspirations of untouchables

themsel!es.

2G

Indeed, &mbed'ar+s assertion that the rights of untouchables could ne!er fully be

protected by caste 3indus seems to be pro!en correct when one eamines the series of

e!ents that lead to the (oona (act in 2G>,. &fter the Third /ound Table conference, the

British interceded into what they belie!ed was a stalemate between the depressed

classes and caste 3indus by issuing the /amsey 5ac1onald &ward. This compromise

document ga!e untouchables an altered form of the separate electorates they desired

?Kelliot 2CC@. ;andhi responded by underta'ing a fast unto death until the pro!ision

for separate electorates was remo!ed. Kelliot writes, ;andhi+s fast unto death against

separate electorates placed his life in &mbed'ar+s hands ?2>>@. If &mbed'ar refused to

gi!e up his ideal of separate electorates, the frail 5ahatma would surely ha!e died.

5oreo!er, once it became 'nown that the cause of his death was related to issues of

untouchables in legislature, caste 3indus would ha!e li'ely retaliated against the

untouchable community with etreme !iolence.

In light of the seriousness of ;andhi+s action, both in terms of the affects it would

ha!e had on his own person and the dangerous situation it created for untouchables, it is

important to note that his moti!ations were connected as much to caste:based prejudices

as they were to a desire to promote the welfare of the Indian people. Kelliot, for eample,

points out discrepancies between the reasons ;andhi used to justify his fast when tal'ing

to untouchables and the eplanation he ga!e close ac7uaintances. In a letter to

untouchable leaders he stated<

I ha!e not a shadow of a doubt that it ?separate electorates@ will pre!ent the natural growth

for the suppressed classes and will remo!e the incenti!e to honourable amends from the

suppressors. 8hat I am aiming at is a heart understanding between the twoH ?Kelliot 2CF@

Let the net day he remar'ed to one of his friends<

,-

)eparate electorates for all other communities will still lea!e room for me to deal with

them, but I ha!e no other means to deal with untouchables. These poor fellows will as'

why I who claim to be their friend should offer )atyagraha ?non:!iolent resistance, i.e. the

fast unto death@ simply because they were granted some pri!ilegesH.ntouchable

hooligans will ma'e common cause with 5uslim hooligans and 'ill caste:3indus ?Kelliot

2CF@.

Besides the fact that one statement appears to be moti!ated by ethical idealism and the

other by political epediency, one must as' how ;andhi could ha!e epected

honourable amends and a heart understanding between untouchables and people of

high caste when he himself referred to them as poor fellows and hooligans in the

company of friends. In another con!ersation, this one on the subject of untouchable

con!ersion to Christianity, he eclaimed, 8ould you preach the ;ospel to a cow6 8ell,

some of the untouchables are worse than cowsHI mean they can no more distinguish

between the relati!e merits of Christianity and 3induism than a cow ?"ohn 8ebster

22B@.

These remar's ha!e been selected to illustrate the formidable gap that can eist

between untouchables and e!en the most well:intentioned Indian leaders. ;andhi was a

!ocal opponent of untouchability and tra!eled some 2,,--- miles across India to educate

people about the problems that arise from its practices9 yet it is clear that his own !iew

was colored by paternalism and, as 0m!edt points out, it is unli'ely that he had a

thorough understanding of the untouchable eperience. 3e claimed to be a leader of the

untouchables but he could ne!er be a leader from the untouchables. (erhaps this would

not be so problematic if ;andhi did not seem to thin' that untouchables were incapable

of leading themsel!es. ;andhi+s beha!ior and the outcome of the (oona (act con!inced

many untouchables that they would ha!e to turn to a member of their own community=

namely &mbed'ar=if they wanted to effect real social change.

,2

&mbed'ar e!entually signed the (oona (act to ma'e ;andhi brea' his fast, and

doing so re7uired him to trade his goal of separate electorates for a significantly increased

number of reser!ed seats. 4or &mbed'ar, the (oona (act constituted a direct insult to the

untouchables+ cause and caused him to doubt the efficacy of using political means alone

for the creation of radical change. &s it turns out, &mbed'ar+s concern was not

unfounded. The system of reser!ation of seats as outlined in the (oona (act was

incorporated into the Indian Constitution in nearly eactly the same form, the end result

being that untouchables were consigned to !ote for their representati!e from

constituencies in which they are always a minority ?/obert 1eliege 2G>:2GB, )elected

&rticles of the Indian Constitution@. In short, the power of untouchable representation

was all but negated by the way in which their representati!es were elected.

&mbed'ar realized that he had forfeited a powerful political safeguard for

untouchables, and felt that he had been forced to do so because of a stubborn politician

who merely pretended to be a religiously moti!ated leader. 0ne of &mbed'ar+s recently

published papers, ;andhi and 3is 4ast, re:eamines the /ound Table conferences, the

/amsay 5ac1onald &ward, and the (oona (act. This F-:page document shows that

&mbed'ar ne!er reco!ered from the way in which the safeguards of the /amsay

5ac1onald &ward were lost. 3e concludes< Hthere has been a tragic end to this fight

of the untouchables for political rights. I ha!e no hesitation in saying that 5r. ;andhi is

solely responsible for this tragedy ?$ritin%s and S"eeches, .ol- . >EE@. Thus 0m!edt

writes that the (oona (act brought &mbed'ar to the final disillusionment with ;andhi

and with 3induism, pro!ing to him that untouchables would ne!er be able to gain the

e7uality they sought while remaining with their nati!e religion ?2FC@.

,,

Thus &mbed'ar+s approach to politics mar's the confluence of two distinct

mo!ements< the 5ahar struggle for social e7uality and the pan:Indian struggle for

independence. <hough the goals of these groups were not mutally eclusi!e, the socio:

cultural differences between their respecti!e leaders 7uic'ly lead to the perception of a

political dichotomy on both parts. 0n the one hand, there were Indian nationalists,

eemplified by ;andhi, who ad!ocated cultural and political unity as the only way of

preser!ing indigenous India in the face of the British raj. .ntouchable acti!ists, on the

other hand, ac'nowledged that in some ways their community had benifitted from British

go!ernment. In addition, their social project assumed the eistence of societal di!isions

along catse lines. <hough they ad!ocated independence, they also !iewed the creation

of a new go!ernment as a means for bringing their dream of social e7uality to fruition.

Thus the defining moment for the untouchable mo!ement occurred at an e!ent

orchestrated by both British and Indians< the signing of the (oona (act in 2G>,. The

e!ents surrounding the pact were significant, not only in pro!ing une7ui!ocally that

&mbed'ar was the political leader of India+s untouchables, but also in laying the

foundation for &mbed'ar+s con!ersion to Buddhism in 2GEC.

,>

Chapter !

Ambedkar and "eligion

In 2G>E &mbed'ar made the following public announcement< Because we ha!e the

misfortune of calling oursel!es 3indus, we are treated thusHI had the misfortune of

being born with the stigma of an .ntouchable. 3owe!er, it is not my fault9 but I will not

die a 3indu, for this is in my power ?Kelliot ,-C@. 1espite the radicalism of &mbed'ar+s

proclamation there were few internal protests from the 5ahar community, and one year

later a 5ahar conference in Bombay unanimously passed a resolution to con!ert from

3induism ?&mbed'ar $ritin%s and S"eeches B->, Kelliot ,-F@. 8e ha!e re!iewed the

political and historical factors that contributed to &mbed'ar+s decision to con!ert from

3induism. 3owe!er his choice also stemmed from a modern understanding of religion

and its functions. This understanding ga!e primacy to the social nature of religion, and it

would lead him to choose and reinterpret Buddhism as the ideal religion for the

untouchables.

.nderstanding of Con!ersion

& recently published manuscript entitled &way from the 3indus eplains

&mbed'ar+s understanding of religion and con!ersion. It responds to four common

arguments against the religious con!ersion of untouchables< 2@ con!ersion can ma'e no

real change in the status of untouchables, ,@ all religions are true and good, and thus

changing religion is futile, >@ the con!ersion of untouchables is moti!ated by political

rather than religious reasons, and B@ the con!ersion of untouchables is neither genuine nor

based on faith ?&mbed'ar B->@. &mbed'ar answers these objections in re!erse order,

,B

stating first that there are numerous eamples throughout history of groups that ha!e

con!erted because of compulsion, or deceit, or with the hope of political gain ?B-B@. In

contrast to these early con!ersions, and to contemporary religion ?referred to as a piece

of ancestral property@, the con!ersion of untouchables would follow their careful

eamination of what they !alue in religion, thus constituting the first case in history of

genuine con!ersion ?B-E@. )econd, &mbed'ar eplains that untouchables would gain no

new political protections under the constitutional law of India if they were to change their

religion ?B-E@. Third, he warns against essentializing religion. &mbed'ar writes that the

science of comparati!e religion has created the false notion that all religions are good

and that there is therefore no reason to discriminate between them ?B-C@. <hough he

gi!es no eamples, he states that religions clearly differ in their conceptions of the

good and that because of this it is possible to assess the merits of one religion with

respect to another ?B-C@.

These three arguments attempt to justify the act of con!ersion from historical,

political, and academic perspecti!es. 3e shows that religious con!ersion is an act

supported by past eamples, the newly emerging science of comparati!e religion, and

contemporary political realities. 3e associates it with ancient history and modern

scholarship. In this way he ad!ocates a contemporary act of con!ersion by placing it on a

continuum with both tradition and modernity. $ot only does con!ersion constitute a

symbolic act that has been ta'ing place for thousands of years, but also indi!iduals are

better e7uipped to ma'e con!ersions than they e!er ha!e been before. In short,

con!ersion is legitimate both in terms of the need it fulfills and the methods that are used.

,E

&mbed'ar then proposes that religious con!ersion will ser!e untouchables

positi!ely. 3e begins by eamining the content and function of religion. The primary

things in religion are its usages, practices and obser!ances, rites and rituals, he states,

Theology is secondary. Its object is merely to nationalize them ?B-F@. &mbed'ar+s

unorthodo use of the word nationalize implies a fundamental relationship between

religious and political systems. Theology, li'e the political process of nationalization,

unifies disparate groups and practice under a common=in this case religious=label. Let

just as distinct groups and indi!iduals comprise the heart of a modern nation:state, so

!aried practices and rituals pro!ide religion with its uni7ue characteristics. In this way

&mbed'ar tries to show that one who describes religion must gi!e priority to religious

practice of religious dogma.

&mbed'ar concludes that religion is fundamentally social in both origin and

function ?B-G@. It originated not through the supernatural but through what &mbed'ar

refers to as )a!age society9 its purpose is to emphasize and uni!ersalize social

!alues, and its function is to act as an agency of social control ?B2-@. 3e 7uotes the

2ncyclo"edia #ritannica<

The function of religion is the same as the function of *aw and ;o!ernmentHIt may not be

used consciously as a method of social control o!er the indi!idualH$onetheless the fact is

that religion acts as a means of social control. &s compared to religion, ;o!ernment and

*aw are relati!ely inade7uate means of social control ?B2-@.

Thus, as ;auri Aiswanathan notes, part of &mbed'ar+s project is to deconstruct the

commonly accepted dichotomy between religious and political systems ?,>E@. Let

whereas &mbed'ar used the lin' between religion and politics to argue for political

,C

solutions to untouchability before the )outhborough Committee, here he uses it to justify

an o!ertly religious act.

&mbed'ar+s choice of order in which to respond to the four criticisms of con!ersion

now becomes clear. 3a!ing legitimized comparati!e analysis of con!ersion, he can show

that this comparison should focus on the ways that religion go!erns society through ritual

and practice. $ot surprisingly, he turns to 3induism and uses a series of eamples to

demonstrate that 3induism cannot offer a model for society that is amenable to

untouchables ?B2,@. These eamples are organized around classical 3indu definitions of

untouchability that are pro!ided in tets such as the Manusmriti ?B2,@. 3e concludes that

untouchables suffer from two burdens as a result of 3induism< social isolation and a

sense of psychological inferiority ?B2>@.

&mbed'ar asserts both of these problems can be sol!ed through religious

con!ersion. & new religion will address the problem of social isolation by pro!iding a

new community, referred to as 'inship, which will counter old forms of social isolation.

&mbed'ar writes, If for the .ntouchables mere citizenship is not enough to put an end

to their isolation and the troubles which ensue therefrom, if 'inship is the only cure then

there is no other way ecept to embrace the religion of the community whose 'inship

they see' ?B2J@. 0nce again, it is clear that &mbed'ar+s thought has shifted since the

)outhborough Committee. &mbed'ar+s aim had been to de!elop true citizenship for

untouchables=defined in terms of representation and the right to hold office=through

the enactment of political controls. Let history presented &mbed'ar with a troubling

dilemma< untouchables were able to procure the rights to representation and office but,

due to the outcome of the (oona (act, they were still powerless in the realm of Indian

,F

politics. Thus he abandons citizenship in fa!or of 'inship a more nebulous term that

denotes membership in a common religious community. (olitical systems, he implies,

are too abstracted from common eperience to sol!e a problem that is rooted in the

untouchables basic understanding of himself and his relationships with others. 8hereas

he once !iewed the solution to untouchability in terms of the relationship of one

community to another ?i.e., untouchables and caste 3indus@, here he phrases it in terms of

a single community+s ability to impro!e its relationship with itself.

&mbed'ar argues that a corresponding label must accompany a new form 'inship.

This label is needed as an assertion of independence to indi!iduals outside the

community and it pro!ides the untouchable with a new way of regarding herself. This

section is the most forcefully worded portion of his essay, and it comes to the heart of

what religious con!ersion means to &mbed'ar<

.nfortunately, names ser!e a !ery important purpose. They play a great part in social

economy. $ames are symbols. %ach name represents association of certain ideas and

notions about a certain object. It is a labelHThe name .ntouchable is a bad name. It

repels, forbids, and stin'sHthe .ntouchables 'now that if they call themsel!es

.ntouchables they will at once draw the 3indu out and epose themsel!es to his wrath

and his prejudiceH4or to be a 3indu is for 3indus not an ultimate social category. The

ultimate social category is caste, nay sub:caste if there is a sub:caste ?B2G@.

This leads &mbed'ar to his final conclusion<

Htwo things are clear. 0ne is that the low status of the .ntouchables is bound upon with

a stin'ing name. .nless the name is changed there is no possibility of a rise in their

social status. The other is that a change of name within 3induism will not do. The

3indu will not fail to penetrate through such a name and ma'e the .ntouchable and

confer himself as an .ntouchable.

The name matters and matters a great deal. 4or, the name can ma'e a re!olution in the

status of the .ntouchables. But the name must be the name of a community outside

3induism and beyond its power of spoilation and degradation. )uch name can be the

property of the .ntouchable only if they undergo religious con!ersion. & con!ersion by

change of name within 3induism is a clandestine con!ersion which can be of no a!ail

?B,-@.

,J

These statements show that the content of religious con!ersion is, according to

&mbed'ar, a change in the way an indi!idual or group !iew themsel!es with respect to

society. It is a social phenomenon9 religious labels are li'e all other linguistic signifiers

in that they ha!e little !alue if there is no second party to witness their use. &mbed'ar

does argue that a change in this outward label will e!entually lead to interior changes

such as increased self:esteem, but it is important to note that personal enhancement is

contingent upon a change in how untouchables present themsel!es to the world. Thus

religious con!ersion allows untouchables to restructure, from the outside in, the

definitions that 3indu society has pre!iously projected upon them.

4ollowing his con!ersion speech of 2G>E, &mbed'ar began a public search for a

religion that would be most appropriate for untouchables. 3e considered Islam,

Christianity, )i'hism, &rya )amajism, and Buddhism, all of which openly recruited

&mbed'ar and his followers ?Kelliot ,-F@. %!entually he chose Buddhism, a religion that

was both nati!e to India and a minority in Indian culture ?there were only 2J-,---

Buddhists in India according to the 2GE2 census@ ?Kelliot 2JF@. It should be noted that

Buddhism+s Indian origins were etremely important to &mbed'ar, who fre7uently

referred Christianity and Islam as foreign religions that would further alienate con!erts

from Indian culture ?Aiswanathan ,>B@. 3owe!er, &mbed'ar formally outlines his

reasons for choosing Buddhism in an article for the Maha #odhi Journal entitled

Buddha and the 4uture of 3is /eligion. 3e writes that he prefers Buddhism to

Christianity and Islam because the Buddha ne!er claimed to ha!e di!ine origin or

powers, he prefers Buddhism to 3induism because the Buddha opposed the caste system

and stood for e7uality between indi!iduals ?>-, >2@. The social gospel of 3induism is

,G

ine7uality, he states, 0n the other hand Buddha stood for e7uality. 3e was the greatest

opponent of Chatur!arna ?>>@. Buddhism, in addition to pro!iding a new name for

untouchables, would assure that this name is fundamentally anti:caste and anti:Brahman.

The Buddhist label is also rooted in liberty, e7uality, fraternity and does not sanctify

or ennoble po!erty ?>J@. .ntouchables are liberated from insults in!ol!ing caste and

class and are pro!ided for in that po!erty will not tied to this new moral system.

Buddhism therefore pro!ides untouchable with a 'inship association that connotes

rationality, egalitarianism, and social change=all of which are re7uirements for a

religion which pro!ides just social go!ernance ?>J@.

&mbed'ar+s Buddhism

There are three primary components of &mbed'ar+s Buddhist message. The first is

the anti:Brahmanical, or destructi!e element. In this respect 1alit Buddhism is the most

recent in a long line of protest mo!ements that ha!e aimed to de:legitimize caste 3indu

appropriation of social and political power. The second component of 1alit Buddhism is

a myth of origin, and the third is a uni7ue form of Buddhist doctrine as presented in 3he

#uddha and His Dhamma. Together, the myth of origin and 3he #uddha and His

Dhamma comprise the constructi!e core of &mbed'ar+s Buddhism. In turn, the

destructi!e and constructi!e elements of 1alit Buddhism combine to pro!ide an alternate

world!iew that legitimizes and stimulates 5ahar social struggles.

4nti*#rahmanism

>-

Tre!or *ing states that that untouchables in modern India can use two methods to

achie!e social mobility. The first is to appropriate the symbols and lifestyle of the upper

castes, and the second is anti:brahmanism, which *ing defines as rejecting the culture

and !alues of the Brahmanical ;reat Tradition while adopting of alternati!e cultural

traditions ?F>@. Nuoting 5. 5. Thomas, *ing describes anti:Brahmanism as the one

modern pattern of social thought which is distinctly Indian in origin and characterH?it is@

the awa'ening of the non:Brahmans to their essential rights of human eistence which

caste has denied them for ages ?FB@. 3e gi!es eamples of se!eral social mo!ements in

India that ha!e used rejection of caste an impetus for action. 3e then places &mbed'ar

within this tradition of anti:Brahmanic social acti!ism ?FJ@. 3e cites well:'nown

eamples such as &mbed'ar+s announcement to con!ert to Buddhism and his depiction of

Brahmanism in 3he 4nnihilation of 5aste to demonstrate that &mbed'ar associated social

e7uality with the destruction of the caste system ?J-:J2@.

Buddhism pro!ides &mbed'ar with an alternati!e cultural tradition that ma'es his

rejection of caste:based 3indu !alues complete. This is most e!ident in the twenty:two

!ows that &mbed'ar prescribed for the con!ert from 3induism to Buddhism. )e!eral do

not e!en mention Buddhism9 and instead aim at separating new Buddhists from their

3indu past. The anti:Brahmanic !ows follow<

2. I shall not recognize Brahma, Aishnu and 5ahesh as gods, nor shall I worship them.

,. I shall not recognize /ama and #rishna as gods, nor shall I worship them.

>. I shall not recognize ;owrie and ;anpati as gods nor shall I worship them.

B. I do not belie!e in the theory of incarnation of ;od.

E. I do not consider the Buddha as the incarnation of Aishnu.

C. I shall not perform shradh for my ancestors, nor shall I gi!e offerings to ;od.

F. I shall not perform any religious rite through the agency of a Brahman.

2G. I hereby reject my old religion 3induism which is detrimental to the prosperity of

human 'ind which discriminates between man and man and accept Buddhism ?(andyan

2>J@.

>2

If one imagines B-,--- con!erts at $agpur as they repeat these !ows in unison she begins

to understand the sociological significance of the &mbed'arite rejection of 3induism.

&mbed'ar+s initial presentation of Buddhism includes an itemized list of forbidden 3indu

practices, and as con!erts swear to abstain from these practices they effecti!ely se!er

themsel!es from a 3indu past. In theory, there was no way of regarding a con!ersion to

Buddhism as anything other than a formal rejection of 3induism. Thus 1alit Buddhism,

in its destructi!e form, is both necessitated and defined by a desire to de:legitimize the

caste system.

Myths of 6ri%in

&mbed'ar+s myth of origin has both a politicalDhistorical and a religious aspect.

&mbed'ar de!elops the new account of untouchable origins most fully in $ho $ere the

Shudras7 How they came to be the 8ourth .arna in the 1ndo*4ryan Society and 3he

9ntouchables: $ho $ere 3hey and $hy 3hey #ecame 9ntouchables7 These boo's are

among the earliest attempts to ma'e a formal study of the Indian caste system, and their

eplicit aim is to present an alternate understanding of caste for both the uneducated and

the intellectual. Briefly, &mbed'ar+s thesis in 3he 9ntouchables is that untouchability

has no origin in race or occupational differences, and that it constitutes an unjust

discrimination concocted by Brahman 3indus ?,B,@. 3e refers to ancient untouchables

throughout as Bro'en 5en, an ancient tribe of indi!iduals who had a culture and

religion distinct from that of the 3indus ?,FG@. These Bro'en 5en were the first

Buddhists and the last ancient Indians to gi!e up the practice of eating beef. 3e ma'es a

special note, howe!er, that the Bro'en 5en were not the same as the Impure ?,B,@. 3e

>,

argues that untouchability was a product of Brahman contempt for Bro'en 5en, due to

their heretical religion and the continuation of eating beef ?,B,@. 3e states, The Bro'en

5en hated the Brahmins because the Brahmins were the enemies of Buddhism and the

Brahmins imposed untouchability upon the Bro'en 5en because they would not lea!e

Buddhism ?>2F@. Thus &mbed'ar se!ers untouchability from its pre!ious associations

with race, purity, and occupation, and lin's it instead to the practice of Buddhism.

&mbed'ar+s preface to 3he 9ntouchables implies that the new understanding of

untouchable origins was meant to be a starting point for further re!olutions in thought.

3e writes<

The eistence of these classes ?untouchables@ is an abomination. In any other country the

eistence of these classes would ha!e led to searching of the heart and to in!estigation of

their origin. But neither of these has occurred to the mind of the 3induH?,>G@

8hat is strange is that .ntouchability should ha!e failed to attract the attention of the

%uropean student of social institutionsHThis boo' may therefore, be ta'en as a pioneer

attempt in the eploration of a field so completely neglected by e!erybody. The boo', if I

may say so, deals not only with e!ery aspect of the main 7uestion set out for in7uiry,

namely, the origin of .ntouchability, but it also deals with almost all 7uestions connected

with it ?,B2@.

&mbed'ar+s boo' pro!ides an assertion of untouchable self:definition in the face of

intellectual apathy and religious discrimination. Its purpose is to shift the way

untouchables thin' about themsel!es and the way caste 3indus and scholars !iew

untouchables. Thus &mbed'ar+s response to the 7uestion of untouchable origins

constitutes of a dual triumph of rationality o!er uninformed religious tradition and of

e7uality o!er caste. <hough he admits to ha!ing used a certain amount of imagination

and hypothesis to fill in historical gaps, &mbed'ar clearly wants others to !iew his wor'

as an empirical historical study. I ha!e at least shown that there eists a preponderance

of probability in fa!our of what I ha!e asserted, he writes, It would be nothing but

>>

pedantry to say that a preponderance of probability is not sufficient basis for a !alid

decision ?#adam 2>@. This places his analysis of caste outside the traditional 3indu

paradigm9 therefore it challenges his critics to follow his mo!e if they wish to respond to

him in 'ind. &s both *ynch and Kelliot document, the notion of using mythic tradition to

eplain unpleasant social conditions was not new to untouchable communities.

&mbed'ar+s project, howe!er, was the first to accomplish this in the name of rational

historical in7uiry and the scientific method.

3he #uddha and His Dhamma

It is important to establish at the outset that &mbed'ar significantly altered the

teachings of the Buddha from pre!ious presentations in writing 3he #uddha and His

Dhamma. )ome critics ne!ertheless go to great lengths to pro!e that &mbed'ar+s

Buddhism does not depart from traditional Thera!adin orthodoy. 1.C. &hir, for

eample, attempts to associate each section of 3he #uddha and His Dhamma with the

(ali Canon, yet the chart he creates is !ague and difficult to !erify. &dditionally, when

&hir reaches his conclusion it becomes clear that the outcome of his project was

predetermined. 8here!er the modern Bodhisatt!a ?&mbed'ar@ has added something of

his own, &hir writes, it is only to present the Buddha+s teachings in the right

perspecti!e ?22,@. 0n the other hand, Christopher Nueen cites two unpublished studies

by &dele 4is'e which carefully analyze &mbed'ar+s use of (ali scriptures. 3e writes,

4is'e documents &mbed'ar+s repeated use of omission, interpolation, paraphrase, shift

of emphasis, and rationalization in passages that are presented as, in &mbed'ar+s words,

Osimple and clear statement?s@ of the fundamental Buddhist thoughts+ ?BJ@. /ichard

>B

Taylor assesses 3he #uddha and His Dhamma in a similar manner< 3e has ta'en what

seemed to him the most rele!ant parts of se!eral Buddhist traditions, edited them,

sometimes drastically, added material of his own, and arranged them in an order ?2BC@.

These remar's suggest that a discussion of 3he #uddha and His Dhamma should

dispense with the 7uestion of if &mbed'ar changed Buddhist doctrine and focus on why

and how this change occurred.

&mbed'ar himself ma'es no pretense of directly transmitting traditional Buddhist

doctrine, and his introduction outlines four ways in these teachings are lac'ing< 2@ The

Buddha could not ha!e had his first great realization simply because he encountered an

old man, a sic' man, and a dying man. It is unreasonable and therefore false to assume

that the Buddha did not ha!e pre!ious 'nowledge of something so common. ,@ The 4our

$oble truths ma'e the gospel of the Buddha a gospel of pessimism. If life is composed

entirely of suffering then there is no incenti!e for change. >@ The doctrines of no:soul,

'arma, and rebirth are incongruous. It is illogical to belie!e that there can be 'arma and

rebirth without a soul. B@ The Bhi''huPs purpose has not been presented clearly. Is he

supposed to be a perfect man or a social ser!ant6 ?Introduction, no page number

gi!en@. <hough there are numerous other ways in which &mbed'ar crafted his boo'

specifically to meet the needs of untouchables, an eamination of these four major

reinterpretations pro!ides sufficient illustration of &mbed'ar+s creation of a Buddhism

for untouchables. 5ore specifically, it shows that &mbed'ar+s Buddhism is centered on a

self:conscious acti!ism that meets the needs of untouchable social mo!ements.

&mbed'ar+s first major reinterpretation in!ol!es the Buddha+s reununciation of

worldly life. 8hereas traditional biographies of the Buddha emphasize the empathy the

>E

young prince felt when he first encountered sufferring, &mbed'ar highlights the strength

of the Buddha+s social conscience during a conflict o!er water rights. &ccording to

&mbed'ar, the Buddha ad!ocated rational and a peaceful resolution of a tribal water

conflict but was unable to gain political le!erage because he lac'ed a majority !ote ?,F@.

3e then went into ehile and became a renunciant because it was the only way to pre!ent

the )a'yas from going to war with a neighboring tribe ?,J@. &mbed'ar omits any

mention of old age, sic'ness, and death. In this account, Buddha+s renunciation is

moti!ated by political eigencies rather than a desire find ultimate truth. Thus the

Buddha becomes a figure similar to a minority politician in contemporary India< his

concerns are social and rational, he clearly has an eceptional moral conscience but he is

not a god, and his reality is shaped by politics that are ultimately beyond his control. The

Buddha+s political difficulties mirror the problems untouchables ha!e gaining proper

representation in the Indian parliament, and the discussion of water rights was a familiar

topic after the 5ahad )atyagraha. These changes, though unorthodo, create a character

for the Buddha that is easily understood by the untouchable community.

&mbed'ar subjects the 4our $oble truths to the same type of interpretation. 3is

description of the first sermon at 1eer (ar' follows<

The centre of his 1hamma is man and the relation of man to man in his life on earth. This

he said was his first postulate. 3is second postulate was that men are li!ing in sorrow, in

misery and po!erty. The world is full of suffering and that how to remo!e this suffering

from the world is the only purpose of 1hamma. $othing else is 1hamma. The recognition

of the eistence of suffering and to show the way to remo!e suffering is the foundation and

basis of his 1hammaH& religion which fails to recognise this is no religion at allHThe

Buddha then told them that according to his dhamma if e!ery person followed ?2@ the (ath

of (urity9 ?,@ the (ath of /ighteousness9 and ?>@ the (ath of !irtue, it would bring about the

end of all suffering ?2,2:2,,@.

&mbed'ar ma'es se!eral ob!ious changes to traditional Thera!adin doctrine. The first

$oble Truth of suffering becomes the second postulate, and the most important

>C

characteristic of Buddhism becomes its concern for human relationships. The second

$oble Truth, that suffering arises from mental cra!ing, is also described in social terms,

as sorrow, misery and po!erty. In turn he refers !aguely to the third $oble Truth of

Cessation as the remo!al of suffering. Nueen+s detailed analysis of &mbed'ar+s

presentation of the 4our $oble Truths re!eals still more ways in which they ha!e been

altered to create a message of social acti!ism. &s the Buddha+s teachings continue it

becomes clear that the (ath of (urity is the 4i!e (recepts, the (ath of /ighteousness is

the %ightfold (ath, and the (ath of Airture is the Ten aramitas, or perfections ?Nueen

EC@. Let &mbed'ar does not present any of these concepts in their traditional format.

)e!eral elements of the %ightfold (ath and the ten perfections are also reinterpreted for a

social contet. The goal of %ightfold (ath, for eample, is to remo!e injustice and

inhumanity that man does to man, rather than nir!ana ?Nueen EF@. $ir!ana itself is then

described as the realization of two fundamental problems< that there was suffering in the

worldHand how to remo!e this suffering and ma'e man'ind happy ?Nueen EF@.

These changes spea' specifically to untouchables in a number of ways. 4irst, there

is a distinct element of anti:Brahmanism in &mbed'ar+s rendering of the 4our $oble

Truths. $othing else is 1hamma, he states, and & religion which fails to recognize this

is no religion at all. <hough &mbed'ar does not criticize other religions in this section

=as he does in other chapters of the boo'=these statements bear close resemblance to

his earlier attac's on 3induism. It is li'ely that con!erts who read 3he #uddha and His

Dhamma would 'now eactly what he was referring to. By incorporating anti:

Brahmanism into the 4our $oble truths=by all accounts the central teaching of

Buddhism=&mbed'ar once again legitimizes the use of Buddhism to oppose old

>F

traditions that are unsatisfactory. )econd, as Nueen notes, &mbed'ar understands that the

traditional presentation of suffering=which places the blame on the cra!ings of each

indi!idual=would alienate Buddhism from the socially and politically oppressed ?EG@.

Thus suffering is described in transitory terms as sorrow, misery, and po!erty.

These unpleasant states lend themsel!es more easily to remedy than the traditional

Buddhist understanding of suffering as an intricate networ' of mental cra!ings. The

focus on cra!ing also lends itself to manipulation by people of power, who can ad!ocate

renunciation instead of responding to the materially based claims of the dispossessed.

Third, by placing the 4our $oble Truths, the %ightfold (ath, and the Ten (erfections in a

social contet he pro!ides religious justification for untouchable social mo!ements.

*astly, and perhaps most importantly, his definition of nir!ana is not only easily

understandable but theoretically attainable within a single lifetime.

&mbed'ar+s eplanation of 'arma and rebirth further legitimizes both the source

and the goal of untouchable social acti!ism. 3e defends the concept of rebirth but

changes the concept of the soul. %ach time a person is reborn his or her soul is then

di!ided and recombined with parts of many other peoples+ souls. There is no single soul

that is reborn o!er and o!er again ?>>>@. Thus &mbed'ar establishes that there is no

inheritance of traits from one lifetime to the net=a direct rebuttal to the ;andhian !iew

of caste. This negates the idea that current social injustices are a result of past misdeeds

and assures untouchables that their new framewor' does not contain the possibility for

religiously sanctioned hierarchy. 3e also eplains that 'arma wor's only within one

lifetime and cannot affect future li!es ?>B-@. & this:worldly emphasis on 'arma gi!es

added significance to societal changes, as each life is now a uni7ue and unrepeatable

>J

opportunity for change and growth. The tas' of impro!ing one+s situation in life thus

ac7uires the utmost importance. 8hereas traditional conceptions of 'arma and rebirth

render material changes insignificant on a cosmological scale, &mbed'ar+s

reinterpretation implies that they ha!e ultimate importance. Thus untouchables are

!indicated in their sense of social outrage and are informed once again of the importance

of social struggle.

*astly, &mbed'ar+s reinterpretation of the role of the mon' shows untouchables that

Buddhism ta'es a proacti!e stance towards radical change. 5on's should not be content

merely to ser!e society=they are instead the acti!e participants and creators of history.

3e writes that the Bhi''hu+s duties are to proselytize for Buddhism and ser!e the laity.

The bhi''hu is commanded specifically to fight to spread dhamma ?BBF@. 8e wage

war, 0 disciples, therefore we are called warriors, the &mbed'ar+s Buddha tells his

disciples, 8here !irtue is in danger do not a!oid fighting, do not be mealy:mouthed

?BBF@. 5on's are not hermetic ascetics who are focused on the attainment of

otherworldly states. /ather, they constitute the dri!ing force behind a re!olution in mind

and body. This and other statements show the reader that Buddhism is a dynamic and

forceful source of social change. 1hamma is the correct go!ernance for society and the

use of force is perfectly acceptable in the endea!or to spread it. In short, these passages

pro!ide precisely the 'ind of moti!ation that a burgeoning social mo!ement of oppressed

people would need.

It is now possible to summarize the salient characteristics of &mbed'ar+s Buddhist

doctrine. Buddhism for untouchables is a fundamentally social message. In addition, this

message must be understood as proacti!e instead of passi!e. It both demands and

>G

pro!ides a means for social change. It is impossible to interpret &mbed'ar+s Buddhism

as acceptance of the status 7uo, and se!eral 'ey elements such as the new understanding

of suffering, 'arma, and nir!ana are easily identifiable with the eperiences of the

oppressed. Therefore &mbed'ar+s Buddhism is self:consciously aware of what it is as

well as what it is not ?i.e. 3induism@. This and the other aspects of &mbed'ar+s

Buddhism mentioned abo!e relate directly to the eperiences of the untouchables, and

thus 3he #uddha and His Dhamma pro!ides an ideology suited specifically for the

present conditions of 5ahar life.

&mbed'ar+s /elationship to Buddhism

&mbed'ar+s relationship to Buddhism is characterized by a !ariety of political,

religious, and historical factors. 0n the one hand, it is clear that the political failure of

the (oona (act pro!ided the primary catalyst for his decision to con!ert to Buddhism.

&mbed'ar realized that citizenship would ne!er lead to full realization of rights if the

go!ernment did not also implement a correcti!e electoral framewor' for untouchables.

&s Aiswanathan writes<

&mbed'ar sought to epose the wide gap between the secular commitment to the remo!al

of ci!il disabilities and the secular state+s persistent functioning within a majoritarian ethic.

3is primary objecti!e thus lay in demonstrating that modern secularism was essentially a

uni!ersalist world!iew stalling the processes of enfranchisement and creating the

conditions for partial, rather than full, citizenship ?,2E@.

This analysis recognizes that &mbed'ar+s adoption of Buddhism was basically an attempt

to replace the ideal go!ernance of secular democracy with religious morality. 3a!ing

realized that an emphasis on rights in terms of citizenship and political participation

would ne!er procure e7uality for untouchables, he created an alternate system=based on