Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Livingston CNN Effect Reconsidered - Again - Problematizing ICT & Global Governance - 2011

Uploaded by

Bo0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views19 pagesThe CNN effect reconsidered (again): problematizing ICT and global governance in The CNN effect research agenda. Early CNN effect research considered policy effects associated with cumbersome satellite uplinks of limited capacity.

Original Description:

Original Title

Livingston CNN Effect Reconsidered_again_problematizing ICT & Global Governance_2011

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe CNN effect reconsidered (again): problematizing ICT and global governance in The CNN effect research agenda. Early CNN effect research considered policy effects associated with cumbersome satellite uplinks of limited capacity.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views19 pagesLivingston CNN Effect Reconsidered - Again - Problematizing ICT & Global Governance - 2011

Uploaded by

BoThe CNN effect reconsidered (again): problematizing ICT and global governance in The CNN effect research agenda. Early CNN effect research considered policy effects associated with cumbersome satellite uplinks of limited capacity.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 19

http://mwc.sagepub.

com/

Media, War & Conflict

http://mwc.sagepub.com/content/4/1/20

The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/1750635210396127

2011 4: 20 Media, War & Conflict

Steven Livingston

governance in the CNN effect research agenda

The CNN effect reconsidered (again): problematizing ICT and global

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism

can be found at: Media, War & Conflict Additional services and information for

http://mwc.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://mwc.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions:

http://mwc.sagepub.com/content/4/1/20.refs.html Citations:

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

What is This?

- Apr 8, 2011 Version of Record >>

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Article

MWC

Media, War & Conflict

4(1) 2036

The Author(s) 2011

Reprints and permission: sagepub.

co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1750635210396127

mwc.sagepub.com

Corresponding author:

Steven Livingston, School of Media and Public Affairs, Elliott School of International Affairs, George

Washington University, 805 21st Street, NW, Washington, DC 20052, USA.

Email: sliv@gwu.edu

The CNN effect reconsidered

(again): problematizing

ICT and global governance

in the CNN effect research

agenda

Steven Livingston

George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA

Abstract

Early CNN effect research considered policy effects associated with cumbersome satellite uplinks

of limited capacity. Today, nearly ubiquitous mobile telephony and highly portable satellite uplinks

enable high-speed data transmission, including voice and video streaming, from most remote

locations. Also, important geopolitical realignments have occurred since the end of the Cold

War. The US is now challenged by new economic and cultural powerhouses, and by the rise of

networked nonstate actors. It is not simply a matter of realignment among nation-states, as the

original CNN effects research noted, but also a realignment between the type, scope and scale

of actors involved in global governance. Rather than confining the argument to a consideration

of media effects on state policy processes, this article argues that important technological and

political developments call for a new research path, one that centers on the relationship between

governance and the nature of a given information environment.

Keywords

CNN effect, complex interdependence, crowdsourcing, event mapping, geographical information

systems (GIS), governance, information regimes, mobile telephony, scale shifting, Ushahidi

CNN effect research focuses on two core questions: first, how might global real-time

television affect state foreign policy processes? Second, how do geopolitical realign-

ments affect the probability and intensity of these potential policy effects?

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Livingston 21

Regarding the first question, researchers have considered whether global television

coverage of distant events accelerates decision cycles or alters policy by adding new

objectives or, conversely, by undermining public support or operational security for exist-

ing ones (Livingston, 1997; Livingston and Eachus, 1995). The second question draws

attention to the geopolitical context of potential media effects on foreign policy. The con-

fidence that policy makers have in the soundness of objectives and in the conduct of policy

reflects the conceptual clarity associated with a particular geopolitical context. The end of

the Cold War, for example, created policy uncertainty for the US (Robinson, 2000, 2002).

Although the CNN effect research agenda has proven quite creative and robust over

the years, it has failed to adjust to important changes in technology and politics.

1

We

should call to mind that initial CNN effect case studies were, on the whole, written prior

to the flourishing of the world wide web.

2

Changes involve more than technology.

Equally important geopolitical realignments have occurred since the end of the Cold

War. Although the US remains a dominant military and political power in the world, new

economic and cultural powerhouses are on the rise (Zakaria, 2008). What is more, inter-

national relations scholars point to the growing importance of nonstate actors in global

affairs (Rosenau and Czempiel, 1992; Singh and Rosenau, 2002). It is not simply a mat-

ter of realignment among nation-states, but also realignment between the type, scope and

scale of actors involved in global politics.

Rather than confine ourselves to consideration of media effects on state policy pro-

cesses, important developments call for a new path, one that centers on the relationship

between governance, on the one hand, and information and communication technology

(ICT) on the other. A more intellectually exciting and politically germane research question

is this: How does the nature of an information environment alter the nature of governance?

(Weiss, 2000; Weiss and Thakur, 2010; Wendt, 1992). Governance encompasses the

complex of formal and informal institutions, mechanisms, relationships, and processes between

and among states, markets, citizens and organizations, both inter- and non-governmental,

through which collective interests on the global plane are articulated, rights and obligations are

established, and differences are mediated. (Weiss and Thakur, 2010)

The point of this article is to suggest why this refocusing of research is necessary and impor-

tant for the development of political communication and international relations theory.

My argument comes in two part. First, I argue that theory building must take into

account the evolving nature of the central independent variable in CNN effects research:

the production of content. Significant changes in technology have removed, to a great

extent, the historical encumbrances to live newsgathering in remote locations. A news

managers decision calculus regarding the distribution of newsgathering resources no

longer involves the same extraordinary costs once associated with such a circumstance.

3

Second, I argue that analyses must look at systems-level effects of a given state of

technological development. It is not only a matter of specific technologies advancing in

ways that affect television, but rather how television itself is a part of and at times indis-

tinguishable from other technologies comprising what I shall refer to as an infosystem.

I will begin with a review of specific advances in satellite newsgathering (SNG) and

then take up the argument concerning infosystems and governance.

4

I close with an

assessment of the benefits and costs of my suggested approach.

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

22 Media, War & Conflict 4(1)

Satellite newsgathering

The 19901 Persian Gulf War was CNNs signature moment. On 17 January 1991, CNN

correspondents John Holliman, Peter Arnett and Bernard Shaw relayed dramatic audio

reports describing the opening hours of the coalition bombing campaign. They did so

using a four-wire circuit running from Baghdad to Amman, Jordan. This relatively

simple technology allowed CNN to offer live audio reports, even after the telephone

lines in Baghdad went dead. In coming days, veteran war correspondent Arnett remained

behind as his colleagues returned to the US. Switching to an Inmarsat-A satellite termi-

nal, he offered riveting and at times controversial reports about the bombing campaign.

Arnetts reporting and the technology he used provides a benchmark for measuring sub-

sequent developments in SNG technology.

Two weeks into the bombing campaign, another technology offered CNN its second

news coup of the war: a live television interview with Saddam Hussein. Unlike the audio-

only Inmarsat-A uplink, this second technology, a C-band flyaway unit, relayed live video.

It was not easy to use, however, as the Washington Posts Tom Shales made clear at the time.

A portable satellite uplink device known as a flyaway had to be taken to Baghdad from

Amman, Jordan, on a flatbed truck, with five more CNN crew members joining Arnett to rig

the device for transmission. Then it became a matter of aiming the portable satellite dish 23,000

miles out into space to the correct transponder of the correct satellite that would beam the image

back to Atlanta for broadcast on CNN. This is, apparently, what took hours and hours to

accomplish. (Shales, 1991)

All of this relied on a growing fleet of communication satellites. Telstar, the first satellite

to relay television transmissions, was launched in 1962. Two years later the first geosta-

tionary satellite, the Syncom 3, was in orbit. In rapid succession, a number of additional

satellites came online. For television news, the launch of Satcom 1 in 1975 was instru-

mental in establishing the technological feasibility of WTBS (in some ways the precur-

sor to CNN), HBO, and the Weather Channel.

5

As important as communication satellites are, the greater breakthrough in SNG may

be in the mobile uplink terminals. Arnetts live uplink in 1991 filled a flatbed truck, while

his Inmarsat-A was the size of a small filing cabinet. During the NATO bombing cam-

paign against targets in Kosovo and Serbia in 1999, television networks offered live

broadcasts from satellite uplink units mounted on the back of trucks similar in size to

those used by express mail delivery services. In Afghanistan in 2001, the rough terrain

meant even smaller uplink units were transported in several hardened containers.

The videophone has enabled television news crews to venture out into the danger

zone in northern Afghanistan, untethered to a customary satellite uplink they need to beat

the other guy on the air with a live shot.

Over rugged mountain routes, crews are able to

tote scaled-down versions of equipment that usually weighs in excess of a ton (Wasserman,

2001).

6

Flyaway satellite uplinks have continued their steady reduction in size, weight, and

expense. Rather than filling cargo holds, flyaway satellite uplinks today fill suitcase-

sized containers. By 2008, Ku-band satellite uplinks came in compact cases and were

found mounted on the rooftop of BMW Mini Coopers (Higgins, 2008). Advances in

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Livingston 23

Codex Video compression have also been a key aspect of the greater capacity to transmit

live from remote locations. Compression reduces the amount of digital information

required to transmit and view video streams (Bier, 2006).

Yet the most significant change in satellite uplink capacity is probably found in

Inmarsat terminals. Originally founded in 1979 as a maritime emergency communication

system, the International Maritime Satellite Organization (Inmarsat) became a private

company in 1999 (Inmarsat, 1999). Today, a BGAN X-Stream terminal transmits at

speeds in excess of 384 kbps for live video broadcasting. As a point of comparison, the

Inmarsat-A used by Arnett offered analog FM voice and telex services at 56 or 64 kbps.

The X-Stream also supports Integrated Services Digital Network (ISDN) at 64 kbps,

allowing it to support email and internet, including the use of Voice Over Internet

Protocol services such as Skype. It can also send large file attachments over a secure

connection at speeds up to 492 kbps. Inmarsat is probably correct in its claim that: As

video quality is vastly improved, news companies can now consider replacing their SNG

trucks with BGAN terminals that use BGAN X-Stream, thus saving money (Inmarsat,

2010). Inmarsat terminals can be carried in a shoulder case, used around the globe with-

out restrictions from satellite frequency regulators, and operated by non-technical per-

sonnel. Set up and satellite connectivity takes minutes.

7

Changes such as these, and many more not taken up in this limited space, have almost

certainly altered the nature of news content and, therefore, possible policy effects

(Livingston and Bennett, 2003; Livingston and Van Belle, 2005). Yet, as important as

these advances in SNG are, they are best understood as a small part of a much greater

revolution in digital technology. The second point of my argument goes beyond a consid-

eration of specific technological effects on policy outcomes. I argue that analyses must

also look at systems-level effects.

Satellite uplinks and other accoutrements of SNG are generally available to wealthy

institutional users, such as news organizations. They allow organizations to temporarily

reach into geographical spaces that are otherwise inaccessible. To use the language of

network theory, an uplink can be thought of as a mobile node that establishes temporary

connections in previously unconnected spaces. Although this is politically important, a

more interesting development involves the use of technologies that help people reach out

of previously inaccessible locations. The greater technological revolution is found in

simple technologies that empower people through the creation of more stable and endur-

ing networks. The extraordinary development of cellular telephony and related technolo-

gies does exactly that. To see the broader contours of the information environment and

its effect on governance, we must spend time outlining these developments.

Cellular telephony and networks

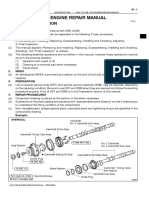

Cellular telephony has been the most rapidly adopted technology in history (International

Telecommunication Union, 2010). By the beginning of 2009, half the global population

paid, in some way, to use a cell phone (see Figure 1). There were an estimated 4.6 billion

mobile phone subscriptions (a number that is growing rapidly), or 6 of every 10 persons on

the planet. This of course underestimates the total population of users, for not all users pay

for the service. Most of the growth in recent years has occurred in the developing world.

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

24 Media, War & Conflict 4(1)

Africa, for example, has had the fastest mobile growth rate in recent years. Mobile pene-

tration soared from 2 percent at the turn of the century to 28 percent by the end of 2009.

Growth rates in some sectors have been nothing less than astonishing. With a total national

population of 38.5 million people, Kenya mobile phone subscriptions jumped from just

200,000 in 2000 to 17.5 million in 2009. About half of all Kenyans subscribe to a mobile

service, with many more using phones made available by friends and family (Engeler,

2010). Ghana recorded a mobile penetration rate that exceeded 60 percent by the end of

2009. It stood at just 22 percent three years before (Nonor, 2009).

Mobile phone penetration in Latin America and the Caribbean was approximately 80

percent in early 2009, well above the world average.

8

Jamaica mobile penetration rate

was 115 percent, Argentina 110 percent, Uruguay 109 percent, and Venezuela 101 per-

cent. Bolivia at 48 percent, Costa Rica at 48 percent, Nicaragua at 52 percent, and Cuba

at 2.9 percent trailed behind (Von/Xchange, 2009). In Asia, India and China are in a

league all their own. India recently surpassed China as the fastest-growing cell phone

market in the world, although it still lags behind China in total subscribers. As of early

2010, it had 143 million subscribers, compared with Chinas 449 million (Vardy, 2010).

Market expansion of services by eager businesses explains most of the growth. The

drive was for profit, not political change. But as Sudanese-born billionaire Mo Ibrahim

9

recently observed:

The mobile industry changed Africa. I must admit we were not smart enough to foresee that.

What we saw is a real need for telecommunication in Africa, and that need had not been

fulfilled. For me that was a business project, but also a political project. (BBC, 2009)

Of greatest interest here are the efforts to expand the reach of cellular telephony to

regions where market economics do not support service, such as in zones of extreme

poverty and insecurity. NGOs and other international organizations seed mobile sys-

tems to gain the social, economic and political benefits accrued to publics by the forma-

tion of networks.

10

Figure 1. A Decade of ICT growth driven by mobile technologies.

Source: ITU World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database.

P

e

r

1

0

0

i

n

h

a

b

i

t

a

n

t

s

'98

*Estimates

'99 '00 '01 '02 '03 '04 '05 '06 '07 '08 '09*

7.1

9.5

17.8

25.9

67.0

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Mobile cellular telephone subscriptions

Fixed broadband subscribers

Mobile broadband subscriptions

Internet users

Fixed telephone lines

An estimated 4.6 bn

subscriptions globally

by the end of 2009

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Livingston 25

Mobiles are not just for making telephone calls (Ekine, 2009).

11

Data transmissions

are the more important aspect of communicating, and the focus of the networking and

collective action activities described here. For example, the objective of MobileActive is

to assist the effectiveness of NGOs around the world who recognize that the 4.5 billion

mobile phones provide unprecedented opportunities for organizing, communications,

and service and information delivery (About MobileActive.org, 2010). In the language

of the social science literature used to contextualize these developments, MobileActive

recognizes the opportunities presented by mobile telephony in the development of gov-

ernance structures and collective action. Another initiative, Movirtu, expands the use of

mobile communication by the rural poor communities in sub-Sahara Africa and South

Asia (Movirtu, 2010). Similarly, FrontlineSMS (2010) freely distributes a software pro-

gram that enables users to send and receive text messages with large groups of people

through mobile phones. Users determine the specific content. Textuality, another initia-

tive, offers several programs based on cellular telephony applications. For example,

Stop Stock-outs is an SMS program to track medicine inventories at the local level in

many African villages (Turretini, 2009). Text Messages Across Nigeria tracks the dis-

tribution of some 63 million mosquito nets. Pill Check enables members of the com-

munity to visit public hospitals to check the availability of drugs at local clinics and

hospital pharmacies (Turretini, 2010). One of Movirtus services is called MXPay.

Movirtu installs a server in a mobile operators switching center that provides access to

basic mobile banking services for those who do not own a mobile handset, a SIM card,

or do not have a bank account.

12

Users are assigned a number and a password that enables

them to log in to the system by way of any available handset. Those who lend their

phones receive an airtime top-up credit, which is calculated as a percentage of the trans-

action.

13

The system can also be used to distribute funds to recipients by aid agencies.

What these examples have in common is the use of networks. Through distributed prob-

lem solving, networks identify problems, monitor conditions, and implement solutions.

Networks and the power of networks involve more than a single technology. In 1999,

a company called Space Imaging launched the worlds first privately owned and oper-

ated high-resolution remote sensing satellite.

14

It offered customers 1-m panchromatic

satellite images and other value-added products (such as a variety of GIS layered maps

and three-dimensional perspectives). Put simply, with the fleet of remote sensing satel-

lites that have been launched since 1999, private organizations, news media, and even

individuals have access to satellite imaging capacity well under 1-m resolution.

15

As a

result, the Iranian nuclear program was revealed in 2003 by an NGO, not the US or any

other country (Aday and Livingston, 2009). The technology removed an old obstacle to

collective action. Previously, nuclear nonproliferation advocates such as the Federal of

America Scientists had to rely on trickles of information from state institutions. This is

an example of costly information. The required information for technical analyses of

potential nuclear sites is now readily available at little to no cost.

There are other examples of networked collective action in low-cost information

environments. Geographic Information Systems (GIS), the geospatial data management

software used to add value to the data collected by remote sensing satellites, has also

advanced in its sophistication and ease of use. Google Earth is probably the most com-

monly seen example of GIS. GIS and remote sensing have been paired with cellular

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

26 Media, War & Conflict 4(1)

telephony and geographical positioning satellites (GPS) to create crowdsourcing

solutions to pressing social needs, such as human rights monitoring and disaster

response.

16

Those who are involved in the use of cellular telephony and GIS are often

referred to as crisis mappers.

Ushahidi testimony in Swahili is a crisis-mapping website developed by Kenyans

to track violence following the flawed 2007 elections (BBC, 2008). Using reports sub-

mitted via the web and mobile phone 45,000 in all, a GIS map was created to visualize

patterns of violence. The service has since grown to a worldwide movement of volun-

teers and users. For example, in South Africa it was used to track xenophobic violence.

A more advanced version of the software was deployed to monitor violence in the eastern

Congo in 2009, while Al Jazeera used it during the Israeli invasion of Gaza in 2009.

Other GIS crowdsourcing services exist, including MapBox. It uses a program called

TileMill (Mapbox, 2009) to create maps using any geographic data set. As with

Ushahidi, the maps are dynamic presentation spaces that update events as often as the

reports come in from mass distributed nodes (cell phones). Voix des Kivus provides a

technology to populations in South Kivu in the eastern Congo that allows them to post

accounts of events, such as outbreaks of disease, crop conditions, and violence (Columbia

Center for the Study of Development of Strategies, 2010).

How can we think about 4.5 billion nodes, along with the other means by which mas-

sively distributed connections create a global chain of connectivity? I take that question

up in the next section.

Information environments and technology

In this section, I argue that the key variable to our analysis is not found in a specific

technology, such as global television, cellular telephony, GIS, GPS, or any other stand-

alone ICT. Rather, it involves an awareness of the characteristics of an information envi-

ronment created by the totality of technologies in a given era, as adapted to particular

economic, cultural and social needs, and in alignment with the social and political insti-

tutions present in that environment (Livingston and Klinkforth, forthcoming). When

speaking to this point, parallel research literatures in sociology, network theory and inter-

national affairs refer to information ecologies, information regimes, digital formations,

and the space of flows (respectively, Levy, 2001; Bimber, 2003; Latham and Sassen,

2005; Castells, 1996). All have to do with the obstacles and opportunities for collective

action, that is to say the nature of organizations and institutions associated with a given

array of technologies.

Castells (1996), for example, argues that information networks redefine and recast the

structure of society. By social structure, he means the social and organizational relation-

ships in production and consumption, experience, and power that provide the contours of

human experience. Put less abstractly, Castells argues that all human relationships are

now global in scale (though significant populations are left off the grid and out of the

global market of goods, services, and ideas) and facilitated by the flow of information

made possible by technology.

Similarly, Latham and Sassen (2005) argue that information and communication tech-

nologies enable new forms of political organization and action, what they call digital

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Livingston 27

formations: The distinctiveness of digital formations can contribute to the rise of social

relations and domains that would otherwise be absent (p. 6, emphases in original). The

flow of digital information and the social structures they create contribute to the rise of

new social relations.

Bimber (2003) refers to information regimes when speaking of a particular moment

of technology and information that facilitates the formation of new associations and

actions. The dominant properties of information determine the nature of an information

regime. An information regime also reflects a set of opportunities and constraints on the

management of information created by these properties; and, finally, the appearance of

characteristic political organizations and structures adapted to those opportunities and

constraints (p. 18). In short, the nature of collective action and governance changes in

accordance with the nature of the information regime.

The key independent variable is not technology, per se, but the nature of social and

political organization and qualities of collective action specific to the contours of oppor-

tunities and constraints emerging from dominant technologies. Bimber notes, for exam-

ple, that in the anti-WTO protests in Seattle in 1999, peripheral organizations and ad hoc

groups used information technology to undertake the kind of political advocacy that

traditionally has been the province of organizations with far greater resources and a more

central position in the political system (p. 2).

Fundamental shifts in available technologies alter information regimes. Bimber calls

these shifts information revolutions: An information revolution disrupts a prior infor-

mation regime by creating new opportunities for political communication and the orga-

nization of collective action (p. 18). He adds: These changes create advantages for

some forms of organization and structure and disadvantages for others, leading to adap-

tations and change in the world of political organizations and intermediaries (p. 18).

17

Bimber is interested in the evolution of information regimes in a single location the

US. From this perspective, regimes come in a linear progression, with change precipi-

tated by information revolutions. Our more comparative perspective benefits from a

change in metaphors, one that captures the interplay among different information envi-

ronments accorded different obstacles and opportunities for collective action. Different

information environments sit astride one another, influencing one another, and infiltrat-

ing one another.

18

As we saw in our review of NGO projects intended to expand the

availability and use of cellular telephony, technologically underdeveloped locations are

seeded by other more advanced information regimes, with NGOs, commercial compa-

nies, and international organizations as change agents.

Rather than regimes, Levy (1999) speaks of communications ecologies. From this

perspective, we might think of the interaction and adaptations of ecosystems as a meta-

phor for talking about change and adaptation in infosystems. An ecosystem is an area

within the natural environment in which abiotic factors, such as rocks and soil interact

with the biotic, such as plants and animals, within a habitat to create a stable system. In

a similar way, myriad factors that are analogous to abiotic elements of an ecosystem,

such as literacy rates, urbanization, availability of electricity, roads, cellular networks, to

name just a few, affect the biotic qualities of an infosystem the nature of collective

action and organizational structures. To understand tree growth one must factor in soil

type, moisture content, slope of the land, forest canopy closure, and other local

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

28 Media, War & Conflict 4(1)

site variables, as well as complex global factors such as climate change. Likewise, to

understand an infosystem requires consideration of local factors and global systems.

New technologies push or are pushed into bordering infosystems.

Technologies are expressed and adopted in different ways and put to different pur-

poses according the needs of local users. There is an indeterminate quality to technolo-

gies that challenges our attempts to offer universal declarations of cause and effect.

Possibilities are opened up with technologies, though whether those possibilities are

realized is the consequence of other factors:

Gutenbergs press did not determine the crisis of the Reformation, the development of modern

European science, or the rise of Enlightenment idealism and the growing power of public

opinion in the eighteenth century; it only conditioned them. It remained an essential element of

the global environment in which these cultural forms arose. (p. 7)

In this regard, infosystems are fluid and adapted to the needs and circumstances of com-

munities embedded in their own unique realities. Mobile telephony in the West is used to

make deals, stay in touch with loved ones, serve as a mobile access point for social

media, and as a gaming platform. In the eastern Congo, cellular networks are used for

basic banking needs, to report rapes and other forms of violence, and even establish a

basic form of identity.

19

Yet despite these alternative expressions of digital capabilities, all are a part of a

global network that looks and behaves as a complex adaptive system (Miller and Page,

2007). Adaptability sometimes comes in the form of organizational structures that reflect

opportunities for collective action, as Bimber and others have noted. Another character-

istic has been referred to by sociologist Sidney Tarrow (2005: 120140) as scale shift-

ing. Scale shifting opens up the possibility that state institutions will be bypassed

altogether in networked flows of images, words, and other symbols. As state structures

are bypassed, traditional media institutions are as well. This possibility goes beyond

consideration of the CNN effect, at least as traditionally understood. Rather, it means that

significant communicative acts with political and social effects bypass states and tradi-

tional media alike. Examples of scale shifting include the use of Facebook, YouTube and

Twitter to bypass Iranian state authorities when transmitting images and accounts of

political protests in 2009 (Livingston and Asmolov, 2010).

Even in the eastern Congo, something like scale shifts occur. There, the problem does

not relate to blocking state authorities, and the shifts do not usually come in the form of

YouTube posting. Instead, Western reporters tell of collecting hundreds, even thousands

of cell phone numbers from people living in villages found miles from the nearest road

(Fessy, 2010; Gettleman, 2010; Zajtman, 2010). Ive gotten a telephone call from a par-

ish priest out in the bush saying, Im hiding under my bed. Were under attack

(Zajtman, 2010).

Discussion

Several immediate benefits emerge when the CNN effect research agenda is recast

in this way. First, it allows us to tap into intellectual currents shared by several social

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Livingston 29

science disciplines, including sociology, political science, behavioral economics, network

theory, theories of contentious politics, geography, and international relations. Even

technical fields such as engineering, computer science, and software development come

into play.

Second, it helps us resolve complex definitional problems about media delivery sys-

tems and content that have arisen since the early stages of CNN effects research. We can

no longer speak of television as a sui generis medium, as we once did when discussing

the CNN effect. Television, YouTube, Twitter, Hulu, and Facebook, to name but a few

options, straddle the blurred borders of digital content.

Third, as with all television programming in the 1990s and before, CNN directed

content at audiences. Today, digital media are interactive and the distinction between

producer and consumer is blurred. As a result, content is often caught up in a recursive

process of saliency reinforcement by both new media, such as Twitter and YouTube, and

traditional media, such as CNN. Traditional media alert audiences to the existence of

new media content online, while new media content feeds traditional media. Recasting

research as I suggest here helps researchers account for these changes.

Fourth, a recasting of the research question also encourages consideration of the tem-

poral complexities of contemporary digital media, complexities that had not emerged

during the early years of CNN effects research. Although the immediacy of real-time

television coverage of events around the world was a key element of televisions pre-

sumed effects on policy processes, newer twists in the experience of time had not

emerged. This has changed, as Castells (2000) notes:

The mixing of times in the media, within the same channel of communication and at the choice

of the viewer/interactor, creates a temporal collage, where not only genres are mixed, but their

timing becomes synchronous in a flat horizon, with no beginning, no end, no sequence. The

timelessness of multimedias hypertext is a decisive feature of our culture, shaping the minds

and memories of children educated in the new cultural context. (p. 492)

The real-time element of global media is but one temporal phase, and perhaps not even

the most important one.

Fifth, the nature of publics is altered by global information flows and scale shifting,

or what Rosenau calls distant proximities. The shared norms, values and affective

attachments emerging from common socialization experiences in what Benedict

Anderson calls imagined communities, the nation-states that rose in the 18th century

with the development of print capitalism and the vernacular press, are no doubt still cen-

tral to identity. People are most centrally members of a public defined by the accident of

birth and geographical proximity. Identities are still mostly rooted in a common language

and shared physical place. Yet the depth of these attachments has weakened. The blend-

ing of local and global experience through global networks is that:

coherence and boundaries of cultures, like those of states, have become porous and often frayed

as other norms and practices intrude through the circulation of ideas and pictures from abroad,

the mobility upheaval, the organizational explosion, (and) the diverse products of a global

economy. (Rosenau, 2003)

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

30 Media, War & Conflict 4(1)

Bennett (2004) speaks to a similar point about the changing nature of publics when

discussing the emergence of transnational social movements:

Loose activist networks adopting self-organizing communication technologies and advocating

multiple issues, multiple goals, and flexible identities not only challenge previous organizational

forms of transnational activism. These networks also challenge social movement theories that

focus on brokered coalitions, ideological framing, and collective movement identities fashioned

around national politics. (p. 213)

Publics, in short, are constructed around shared norms and values but without the pre-

viously necessary supposition of geographical proximity. This opens new fields of

public opinion and information (media) research, though conceived of in almost

entirely new ways.

These are a few of the possible benefits to a recasting of the research questions asked

about media. Yet what about the second half of the CNN effects research agenda: policy?

What are some of the possible benefits to our consideration of policy processes?

First, redirecting the CNN effects research along the path I have suggested encour-

ages consideration of governance, a concept that, while inclusive of state policy dynam-

ics, opens up consideration of other important actors.

20

The locus of authority for global

governance is more diffuse than before. States are not going to disappear anytime soon,

if they ever do, but they are no longer alone in addressing global challenges. Tarrow

speaks of complex internationalism and OBrien of complex multilateralism (OBrien

et al., 2000). International institutions have emerged at the core of an increasingly com-

plex international society around which NGOs, social movements, religious groups,

trade unions, and business groups cluster (Tarrow, 2005: 27).

As originally conceptualized, governance was closely linked to the effectiveness of

governments. In 1992, Rosenau and Czempiel pointed to new forms of governance

without government. Global problem solving and coordination of collective action

included a greater array of non-state actors than many had previously recognized. In the

eastern region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, far from the poorly functioning

capital Kinshasa, governance, thin in places as it is, comes from UN agencies and logisti-

cal structures, and from a host of NGOs operating in the area (The International Rescue

Committee, 2010; see also http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/monuc/,

accessed May 2010). As Rosenau remarks in Distant Proximities (2003), his magisterial

treatment of politics in a networked world:

A broad conception of governance also requires breaking out of the conceptual jails in which

we have long been ensconced. To do so it is useful to start at the beginning and treat politics and

governance as social processes that transcend state and societal boundaries so thoroughly as to

necessitate the invention of new (conceptual) wheels. (p. 394)

Though rarely recognized by establishment international relations theorists, the CNN

effect research agenda concerns questions about the nature of the international system of

governance. The reformulation I offer here presents a necessary corrective to an uncriti-

cal acceptance of a single strain of international relations theory structuralism, or what

is most commonly called neorealism. Neorealists underplay human agency, values,

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Livingston 31

norms of behavior and conduct. In their view, the international system is populated by

formally equal sovereign states situated in a system of anarchy. States therefore act

according to the logic of self-help; they must not subordinate their own interest to the

interest of others (Mearsheimer, 2003; Waltz, 1979). Survival, often by military means,

is the paramount imperative of states. In this respect, the CNN effect can be understood

as a hypothesis concerning noise in a system of power balancing among nation states.

Global media create pressures that are said to skew calculations of national interest

(Miller, 2007). In short, media content was a distraction from the pursuit of national

interest that is essential for survival in a power system situated in anarchy.

Other theoretical constructs see the world and medias role in it differently.

Keohane and Nye (1989[1977]), for example, offer a complex interdependence model

of international affairs, what is more often called neoliberalism. Various, complex

transnational connections (interdependencies) between states and nonstate actors are

rooted in at least semi-cooperative relations governed by norms and regimes. Military

capabilities play a diminished role in such a system, at least insofar as states find a basis

for cooperation. Second, international relations constructivist theory places an even

greater value on the creation and propagation of norms and values (Biersteker and Weber,

1996; Finnemore, 1996; Wendt, 1992). Just as political communication research would

benefit from a greater awareness of its fit with the various streams of international rela-

tions thought, both neoliberalism and constructivism would benefit from a richer theo-

retical understanding of media (or ICT). This presents an underdeveloped opportunity

for cross-disciplinary research and collaboration.

I have argued that changes in ICT and, consequently, the nature of global governance

call for a recasting of the core research questions of CNN effects research. It seems quite

clear that one possible cost associated with the adoption of my call for a new research

paradigm is the discontinuity with past research findings. We seem not to be talking

about the same research. One might also fear a loss of parsimony. There is, to be sure,

parsimony in past theoretical constructs. Is there evidence that content X, presented as it

was, led to policy outcome Y? Speaking of infosystems and governance structures dimin-

ishes this elegance. Two responses come to mind, though neither can be explored in

depth in the space available.

First, there is nothing in what I have said that calls for a wholesale abandonment

of key elements of past research design. Scholars can still untangle discrete policy

decisions, though hopefully with an awareness that policy now is the product of com-

plex internationalism or complex multilateralism (OBrien et al., 2000). We can

still focus on television, though with an awareness that television comes in several

forms and with different temporal and spatial qualities that complicate a singular

focus on immediacy. But turning attention to information environments and gover-

nance allows scholars to embrace important questions about nonstate actors and new

technologies.

Finally, I would say that instead of thinking of my suggestions as a call to recast the

CNN effects paradigm, it might be thought of as a recognition that CNN effect research-

ers have been at the forefront of a prescient examination of the effects of ICT (early SNG

systems) on forms of global governance. Complex internationalism and the rise of net-

worked systems of governance created by ICTs conditioning of new opportunity and

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

32 Media, War & Conflict 4(1)

constraints emerged at the dawn of what Castells has called the microelectronic revolution

in the 1980s and 90s. Understood in this way, the CNN effects research agenda captured

the shift in structures of global governance. It was a move away from hierarchical insti-

tutional structure characteristic of what Bimber calls the third information regime, to the

fourth information regime. In the former, information is costly, scarce and organized and

maintained by hierarchical organized structures, such as the formal institutions of nation

states. This is the neorealist system of global governance. But in the fourth information

regime, what Bimber (2003) calls post-bureaucratic politics, information is relatively

abundant, low-cost, and distributed fluidly among horizontally organized networks

(p. 104). This is, it seems, what George Kennan and other realists residing in the halls of

institutional power sensed in 1993. A new system of global governance was emerging.

My call, therefore, is to continue the prescient, groundbreaking research that has

always characterized the field. To do anything else would be to turn our backs on our

own accomplishments.

Notes

1. For a wonderful exegesis of the literature, see Gilboa (2005).

2. Computer scientist Tim Berners Lee wrote a proposal in March 1989 for what would even-

tually become the world wide web. The web however, did not begin to grow until Mosaic

became available in early 1993.

3. In more technical and regulatory terms for which there is no space for further discussion in

this article, new instruments of newsgathering are not subject to the same regulatory encum-

brances experienced by the satellite uplinks used in the 1990s. Therefore, ease of use and lack

of regulation would also be counted among the factors altering the calculus to cover or not

cover a remote event or circumstance.

4. For much of my understanding of SNG, I am indebted to Jonathan Higgins for his personal

communication and many publications (see Higgins, 2007; see also his newsletter, http://

www.beaconseek.com/los.asp).

5. By the end of 1976, there were 120 satellite transponders available over the US. Each of these

analog transponders was capable of relaying one television channel. With digital video data

compression, several video and audio channels can now travel through a single transpon-

der. By 2010, Europes Eutelsat constellation alone offered 609 transponders in stable orbit,

mostly over Europe, Africa and Asia (see http://www.eutelsat.com/satellites/satellite-fleet.

html, accessed 13 May 2010). Starting in 2008, pioneering Intelsat offered another 2175

transponders with coverage around the globe (see http://www.intelsat.com/_files/investors/

financial/2008/2Q-2008-Fact-Sheet.pdf, accessed 13 May 2010). As of 2010, there are now

approximately 560 satellites operating in earth orbit (see http://www.wisegeek.com/how-

many-satellites-are-orbiting-the-earth.htm, accessed 15 May 2010). As important as satellites

are to the live remote data transmissions found at the heart of CNN effects research, undersea

cable is the more commonly used transmission technology. About 80 percent of global data

transmission uses undersea cables (see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v1JEuzBkOD8,

accessed 15 May 2010; see also http://image.guardian.co.uk/sys-images/Technology/Pix/pic-

tures/2008/02/01/SeaCableHi.jpg, accessed 15 May 2010).

6. In April 2001, CNN producer/correspondent Lisa Rose Weaver used a videophone to trans-

mit live images of the release of the crew members of an American surveillance plane from

Hainan Island. These images were thought to be the first unauthorized live television pictures

ever transmitted from China.

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Livingston 33

7. Perhaps the best way to appreciate this technology is to watch a video demonstration (see

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2VNDG403axQ&NR=1; http://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=Nc2FtBT6lFQ&feature=related; http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BmTM-

32WydQ&feature=related).

8. The number of rising mobile phone companies operating in Africa, the Middle East, and the

Americas is quite long and impressive (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_mobile_net-

work_operators_of_the_Americas; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_mobile_network_

operators_of_the_Middle_East_and_Africa, accessed 17 May 2010).

9. Ibrahim founded Mobile Systems International in 1989 and Celtel in 1998.

10. This section of my article reflects several weeks of field research in Senegal, Nigeria, Kenya,

the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, and South Africa. I would like to thank

the Africa Strategic Research Center for its generous support of my work. This section also

reflects experiences in Afghanistan in 2009 and 2010. That work was supported by the Cana-

dian International Development Agency.

11. This is true in the US, too. Calling is no longer the principal function of mobile devices (see

Wortham, 2010).

12. MXPay is similar to other cell phone-based banking services, except for the phone-sharing

feature. The most well-known and widely used is M-Pesa in Kenya (http://www.safaricom.

co.ke/index.php?id=745, accessed 18 May 2010). MTN Mobile Money is another example

(http://www.mtn.com/ProductsServices/MTNMobileMoney, accessed 18 May 2010).

13. See http://movirtu.com/index.html, accessed 18 May 2010. Because they have fixed resi-

dences and lines of credit with a banking service, most Westerners pay their mobile fees at the

end of a billing cycle. People in the developing world use pay-as-you-go plans that involve

the purchase of minutes preloaded on a sim card. This is sometimes referred to as topping

up. Vendors of minutes and sim cards have become ubiquitous in some African, Indian, and

Latin American cities.

14. Space Imaging is now GeoEye Inc. It was formed after Orbital Imaging Corporation (or

ORBIMAGE) acquired Space Imaging in 2006 (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IKONOS,

accessed 18 May 2010).

15. For an inventory to 2008, see Stoney (2010).

16. The word crowdsourcing was coined by Howe (2006). Howe stated that because technology

creates the ability to tap into collective intelligence, the gap between experts and amateurs,

qua elements in a collective, has been diminished (Brabham, 2008; see also Shirky, 2008).

17. Bimber (2003) emphasizes that he does not equate new technology per se with information

revolutions. One cannot simply focus on the latest gadget. His approach instead is to ask when

the properties of information and communication have changed abruptly, and then inquiring

how such changes influenced politics (p. 20).

18. Thinking of it in this way allows researchers to find inspiration in the diffusion of innovation

research literature (see Rogers, 1983).

19. People in poor indigenous communities are born and die without the official recognition

afforded most persons in developed communities. They do not possess birth certificates,

graduation diplomas, marriage certificates, or death certificates. One of the benefits associ-

ated with the Movirtu system of cloud telephony described earlier is the creation of a new

form of identity. Movirtu assigns a unique user number to each customer. In this regard it is

analogous to a passport number or a national identity number. This may be the only official

identification ever given to some customers. I wish to thank Jose Pablo Baraybar, Executive

Director of Equipo Peruano de Antropologia Forense (EPAF), for helping me understand this

aspect of life and death for the rural poor. His work as a forensic anthropologist, responsible

for identifying the remains of impoverished victims of war all over the world, is made more

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

34 Media, War & Conflict 4(1)

challenging by a common lack of official existence in the first place (interview, Lima, Peru,

12 August 2009).

20. A regime is defined by Krasner (1982) as a set of explicit or implicit principles, norms, rules,

and decision making procedures around which actor expectations converge in a given issue-

area (p. 499). This definition is intentionally broad, and covers human interaction ranging

from formal organizations, such as states and supra-state organizations, to informal groups.

As I emphasize throughout this article, regimes need not be composed of states.

References

About MobileActive.org (2010) Available at: http://mobileactive.org/about

Aday S and Livingston S (2009) NGOs as intelligence agencies: the empowerment of transnational

advocacy networks and the media by commercial remote sensing in the case of the Iranian

nuclear program. Geoforum 40(4): 514522.

Al Jazeera (2009). Available at: http://labs.aljazeera.net/warongaza/

BBC (2008) Kenyas Dubious Election. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7175694.stm

BBC (2009) Mo Ibrahims Mobile Revolution. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/8309396.

stm

Bennett WL (2004) Social movement beyond borders: organization, communication, and political

capacity in two eras of transnational activism. In: Della Porta D, Tarrow S (eds) Transnational

Protest and Global Activism. Boulder, CO: Rowman & Littlefield, 203226.

Bier J (2006) Introduction to video compression. EE Times. Available at: http://www.eetimes.

com/design/signal-processing-dsp/4013042/Introduction-to-video-compression

Biersteker TJ and Weber C (1996) State Sovereignty as Social Construct. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Bimber, B. (2003) Information and American Democracy: Technology in the Evolution of Political

Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brabham DC (2008) Crowdsourcing as a model for problem solving: an introduction and cases.

Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 14(1):

7590.

Castells M (1996) The Rise of the Network Society (The Information Age: Economy, Society and

Culture, Vol. 1), 2nd edn. Cambridge, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Castells M (2000) The Rise of the Network Society (The Information Age: Economy, Society and

Culture, Vol. 1), 2nd edn. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Columbia Center for the Study of Development of Strategies (2010) Event Mapping in Congo.

Available at: http://cu-csds.org/projects/event-mapping-in-congo/

Ekine S (ed.) (2009) SMS Uprising: Mobile Activism in Africa. Oxford: Pambazuka Press.

Engeler E (2010) Poor but networked: UN says cell phone use surging. Physorg.com, 23 February.

Available at: http://www.physorg.com/news186144656.html

Fessy T (2010) Interview, BBC, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 13 April.

Finnemore M (1996) National Interests in International Society. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University

Press.

FrontlineSMS (2010) Available at: http://www.frontlinesms.com/

Gettleman J (2010) Interview, The New York Times, Nairobi, Kenya, 23 April.

Gilboa E (2005) The CNN effect: the search for a communication theory of international relations.

Political Communication 22: 2744.

Higgins J (2007) Satellite Newsgathering. Woburn, MA: Reed Educational and Professional

Publishing.

Higgins J (2008) NAB roundup. Line of Sight 13 (Spring). Available at: http://www.swe-dish.com/

products/suitcase-systems/cct90.html

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Livingston 35

Howe J (2006) The rise of crowdsourcing. Wired. Available at http://www.wired.com/wired/

archive/14.06/crowds.html

Inmarsat (1999) Our Satellites. Available at: http://www.inmarsat.com/About/Our_satellites/

default.aspx

Inmarsat (2010). Available at: http://www.inmarsat.com/?language=EN&textonly=False

The International Rescue Committee (2010) The IRC in Democratic Republic of Congo. Available

at: http://www.theirc.org/where/congo

International Telegraphic Union (2010) The World in 2009: ICT Facts and Figures. Available at:

http://www.itu.int/net/pressoffice/backgrounders/general/pdf/3.pdf

Kelly J (2008) Analysis and mapping. Morningside Analytics. Available at: http://morningside-

analytics.com

Keohane R and Nye J (1989[1977]) Power and Interdependence: World Politics in Transition.

Boston, MA: Little-Brown.

Krasner SD (1982) Structural causes and regime consequences: regimes as intervening variables.

International Organization 36(2): 497510.

Latham R and Sassen S (2005) Digital formations: constructing an object of study. In: Latham R,

Sassen S (eds) Digital Formations: IT and New Architectures in the Global Realm. Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press.

Levy P (1999) Collective Intelligence: Mankinds Emerging World in Cyberspace. New York:

Basic Books.

Levy P (2001) Cyberculture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Livingston S (1997) Clarifying the CNN Effect (Research Paper R-18): Kennedy School of

Government, Harvard University. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Livingston S and Asmolov G (2010) Networks and the future of foreign affairs reporting.

Journalism & Mass Communication 11(5): 745760.

Livingston S and Bennett WL (2003) Gatekeeping, indexing, and live-event news: is technology

altering the construction of news? Political Communication 20(4): 363380.

Livingston S and Eachus T (1995) Humanitarian crises and U.S. foreign policy: Somalia and the

CNN effect reconsidered. Political Communication 12(4): 413429.

Livingston S and Klinkforth K (forthcoming) Narrative power shifts: exploring the role of ICTs

and informational politics in transnational advocacy. Political Communication 6.

Livingston S and Van Belle D (2005) The effects of satellite technology on newsgathering from

remote locations. Political Communication 22(1): 4562.

Mapbox (2009) TileMill. Available at: http://mapbox.com/tools/tilemill

Mearsheimer JJ (2003) The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: W.W. Norton.

Miller DB (2007) Media Pressure on Foreign Policy: The Evolving Theoretical Framework.

Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Miller JH and Page SE (2007) Complex Adaptive Systems: An Introduction to Computational

Models of Social Life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Movirtu (2010) Movirtu. Available at: http://www.movirtu.com/index-4.html

Nonor D (2009) Ghana: mobile penetration rate to hit 60 percent by end of year. AllAfrica.com.

Available at: http://allafrica.com/stories/200908110996.html

OBrien R et al. (2000) Contesting Global Governance: Multilateral Economic Institutions and

Global Social Movements. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Robinson P (2000) The policymedia interaction model: measuring media power during a humani-

tarian crisis. Journal of Peace Research 37(5): 613633.

Robinson P (2002) The CNN Effect: The Myth of News Media, Foreign Policy and Intervention.

London: Routledge.

Rogers EM (1983) Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press.

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

36 Media, War & Conflict 4(1)

Rosenau JN (2003) Distant Proximities: Dynamics beyond Globalization, illus. edn. Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rosenau JN and Czempiel E (1992) Governance without Government: Order and Change in

World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shales T (1991) On CNN, waiting for Saddam. The Washington Post, 30 January: B1.

Shirky C (2008) Here Comes Everybody. New York: Penguin.

Singh J and Rosenau J (2002) Information Technologies and Global Politics: The Changing Scope

of Power and Governance. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Stoney W (2010) American Society of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing Guide to Land Imaging

Satellites. Available at: http://www.asprs.org/news/satellites/ASPRS_DATABASE_021208.pdf

Tarrow S (2005) The New Transnational Activism, illus. edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Turretini E (2009) Pill-Check SMS the cure? Textually.org. Available at: http://www.textually.

org/textually/archives/2009/09/024456.htm

Turretini E (2010) Parsons Students Use SMS Technology to Get Medicines to African Villages.

Available at: http://www.textually.org/textually/archives/2010/04/025882.htm

Vardy N (2010) India: The worlds looming #1 cellular market. The Global Guru. Available at:

http://www.theglobalguru.com/article.php?id=88&offer=GURU

Von/Xchange (2009) Latin America Mobile Penetration Reaches 80%. Available at: http://www.

von.com/news/2009/07/latin-america-mobile-penetration-reaches-80.aspx

Waltz KN (1979) Theory of International Politics. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Pr Inc.

Wasserman, E (2001) The videophone war. American Journalism Review. Available at: http://

www.ajr.org/Article.asp?id=2780

Weiss TG (2000) Governance, good governance and global governance: conceptual and actual

challenges. Third World Quarterly 21(5): 795814.

Weiss TG and Thakur R (2010) The UN and Global Governance: An Unfinished Journey.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Wendt A (1992) Anarchy is what states make of it: the social construction of power politics.

International Organization 46(2): 391425.

Wortham J (2010) Cellphones now used more for data than for calls. The New York Times, 13

May. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/14/technology/personaltech/14talk.

html?scp=1&sq=cell%20phone%20data&st=Search

Zajtman A (2010) Interview, France 24, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 13 April.

Zakaria F (2008) The Post-American World. New York: W.W. Norton.

Biographical note

Steven Livingston is Professor of Media and International Affairs at the George

Washington University where he holds appointments in the School of Media and Public

Affairs and the Elliott School of International Affairs.

at UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek on April 21, 2013 mwc.sagepub.com Downloaded from

You might also like

- How To Keep Score For A Softball GameDocument19 pagesHow To Keep Score For A Softball GameBo100% (1)

- John Stuart Mill's Theory of Bureaucracy Within Representative Government: Balancing Competence and ParticipationDocument11 pagesJohn Stuart Mill's Theory of Bureaucracy Within Representative Government: Balancing Competence and ParticipationBoNo ratings yet

- J S Mill, Representative Govt.Document7 pagesJ S Mill, Representative Govt.Ujum Moa100% (2)

- Info Pack 2014Document27 pagesInfo Pack 2014BoNo ratings yet

- TN GodfatherDocument3 pagesTN GodfatherBoNo ratings yet

- The Libertarian Philosophy of John Stuart MillDocument17 pagesThe Libertarian Philosophy of John Stuart MillPetar MitrovicNo ratings yet

- Muller, E.R. (2010) - Policing & Accountability in The NLDocument11 pagesMuller, E.R. (2010) - Policing & Accountability in The NLBoNo ratings yet

- Boin, A., Kuipers, S. & Overdijk, W. (2013) - Leadership in Times of Crisis: A Framework For AssessmentDocument13 pagesBoin, A., Kuipers, S. & Overdijk, W. (2013) - Leadership in Times of Crisis: A Framework For AssessmentBoNo ratings yet

- Derthick, M. (2007) - Where Federalism Didn't FailDocument12 pagesDerthick, M. (2007) - Where Federalism Didn't FailBoNo ratings yet

- Turner, B. (1976) - The Organizational and Interorganizational Development of Disasters, Administrative Science Quarterly, 21 378-397Document21 pagesTurner, B. (1976) - The Organizational and Interorganizational Development of Disasters, Administrative Science Quarterly, 21 378-397BoNo ratings yet

- Derthick, M. (2007) - Where Federalism Didn't FailDocument12 pagesDerthick, M. (2007) - Where Federalism Didn't FailBoNo ratings yet

- Sullivan Review Godfather DoctrineDocument3 pagesSullivan Review Godfather DoctrineBoNo ratings yet

- Engert & Spencer IR at The Movies Teaching and Learning About International Politics Through Film Chapter4Document22 pagesEngert & Spencer IR at The Movies Teaching and Learning About International Politics Through Film Chapter4BoNo ratings yet

- Essay Smaele Access To Information As A Crucial Element in The Balance of Power Between Media & PoliticsDocument16 pagesEssay Smaele Access To Information As A Crucial Element in The Balance of Power Between Media & PoliticsBoNo ratings yet

- The More Things Change The More They Stay The SameDocument3 pagesThe More Things Change The More They Stay The SameBoNo ratings yet

- Wraith Et Al The MucopolysaccharidosesDocument9 pagesWraith Et Al The MucopolysaccharidosesBoNo ratings yet

- v39 I2 08-Bookreview Godfather DoctrineDocument2 pagesv39 I2 08-Bookreview Godfather DoctrineBoNo ratings yet

- Expert Paper Perl Terrorism, The Media, and The GovernmentDocument14 pagesExpert Paper Perl Terrorism, The Media, and The GovernmentBoNo ratings yet

- J Hist Med Allied Sci 2014 Kazanjian 351 82Document32 pagesJ Hist Med Allied Sci 2014 Kazanjian 351 82BoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 An Averted Threat To DemocracyDocument20 pagesChapter 9 An Averted Threat To DemocracyBoNo ratings yet

- Update '89: Alvin E. Friedman-Kien, MD, Symposium DirectorDocument13 pagesUpdate '89: Alvin E. Friedman-Kien, MD, Symposium DirectorBoNo ratings yet

- Expert Paper Bakker & de Graaf Lone WolvesDocument8 pagesExpert Paper Bakker & de Graaf Lone WolvesBoNo ratings yet

- "Patient Zero": The Absence of A Patient's View of The Early North American AIDS EpidemicDocument35 pages"Patient Zero": The Absence of A Patient's View of The Early North American AIDS EpidemicBo100% (1)

- Acute Airway Obstruction in Hunter Syndrome: Case ReportDocument6 pagesAcute Airway Obstruction in Hunter Syndrome: Case ReportBoNo ratings yet

- Randy M. Shilts 1952-1994 Author(s) : William W. Darrow Source: The Journal of Sex Research, Vol. 31, No. 3 (1994), Pp. 248-249 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 02/09/2014 13:37Document3 pagesRandy M. Shilts 1952-1994 Author(s) : William W. Darrow Source: The Journal of Sex Research, Vol. 31, No. 3 (1994), Pp. 248-249 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 02/09/2014 13:37BoNo ratings yet

- Tolun 2012 A Novel Fluorometric Enzyme Analysis Method For Hunter Syndrome Using Dried Blood SpotsDocument3 pagesTolun 2012 A Novel Fluorometric Enzyme Analysis Method For Hunter Syndrome Using Dried Blood SpotsBoNo ratings yet

- Health Education Journal 1988 Articles 104Document2 pagesHealth Education Journal 1988 Articles 104BoNo ratings yet

- Stem-Cell Transplantation For Inherited Metabolic Disorders - HSCT - Inherited - Metabolic - Disorders 15082013Document19 pagesStem-Cell Transplantation For Inherited Metabolic Disorders - HSCT - Inherited - Metabolic - Disorders 15082013BoNo ratings yet

- Wetenschappelijke Artikelen Over Bone Marrow Transplant HunterDocument11 pagesWetenschappelijke Artikelen Over Bone Marrow Transplant HunterBoNo ratings yet

- Sohn 2013. Phase I-II Clinical Trial of Enzym Replacement Therapy MPS IIDocument8 pagesSohn 2013. Phase I-II Clinical Trial of Enzym Replacement Therapy MPS IIBoNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Markle 1999 Shield VeriaDocument37 pagesMarkle 1999 Shield VeriaMads Sondre PrøitzNo ratings yet

- 110 TOP Survey Interview QuestionsDocument18 pages110 TOP Survey Interview QuestionsImmu100% (1)

- NBPME Part II 2008 Practice Tests 1-3Document49 pagesNBPME Part II 2008 Practice Tests 1-3Vinay Matai50% (2)

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Bread and Pastry Production NC IiDocument3 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in Bread and Pastry Production NC IiMark John Bechayda CasilagNo ratings yet

- Examination of InvitationDocument3 pagesExamination of InvitationChoi Rinna62% (13)

- Speech Writing MarkedDocument3 pagesSpeech Writing MarkedAshley KyawNo ratings yet

- Astrology - House SignificationDocument4 pagesAstrology - House SignificationsunilkumardubeyNo ratings yet

- Bandwidth and File Size - Year 8Document2 pagesBandwidth and File Size - Year 8Orlan LumanogNo ratings yet

- GASB 34 Governmental Funds vs Government-Wide StatementsDocument22 pagesGASB 34 Governmental Funds vs Government-Wide StatementsLisa Cooley100% (1)

- Contextual Teaching Learning For Improving Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Course On The Move To Prepare The Graduates To Be Teachers in Schools of International LevelDocument15 pagesContextual Teaching Learning For Improving Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Course On The Move To Prepare The Graduates To Be Teachers in Schools of International LevelHartoyoNo ratings yet

- MM-18 - Bilge Separator - OPERATION MANUALDocument24 pagesMM-18 - Bilge Separator - OPERATION MANUALKyaw Swar Latt100% (2)

- Toshiba l645 l650 l655 Dabl6dmb8f0 OkDocument43 pagesToshiba l645 l650 l655 Dabl6dmb8f0 OkJaspreet Singh0% (1)

- CH 19Document56 pagesCH 19Ahmed El KhateebNo ratings yet

- How To Use This Engine Repair Manual: General InformationDocument3 pagesHow To Use This Engine Repair Manual: General InformationHenry SilvaNo ratings yet

- IndiGo flight booking from Ahmedabad to DurgaPurDocument2 pagesIndiGo flight booking from Ahmedabad to DurgaPurVikram RajpurohitNo ratings yet

- Abbreviations (Kısaltmalar)Document4 pagesAbbreviations (Kısaltmalar)ozguncrl1No ratings yet

- Popular Restaurant Types & London's Top EateriesDocument6 pagesPopular Restaurant Types & London's Top EateriesMisic MaximNo ratings yet

- 2010 Economics Syllabus For SHSDocument133 pages2010 Economics Syllabus For SHSfrimpongbenardghNo ratings yet

- Adic PDFDocument25 pagesAdic PDFDejan DeksNo ratings yet

- FSW School of Education Lesson Plan Template: E1aa06cb3dd19a3efbc0/x73134?path JavascriptDocument7 pagesFSW School of Education Lesson Plan Template: E1aa06cb3dd19a3efbc0/x73134?path Javascriptapi-594410643No ratings yet

- Prac Research Module 2Document12 pagesPrac Research Module 2Dennis Jade Gascon NumeronNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Conflicts and PeacekeepingDocument2 pagesEthnic Conflicts and PeacekeepingAmna KhanNo ratings yet

- Kedudukan Dan Fungsi Pembukaan Undang-Undang Dasar 1945: Pembelajaran Dari Tren GlobalDocument20 pagesKedudukan Dan Fungsi Pembukaan Undang-Undang Dasar 1945: Pembelajaran Dari Tren GlobalRaissa OwenaNo ratings yet

- List of Parts For Diy Dremel CNC by Nikodem Bartnik: Part Name Quantity BanggoodDocument6 pagesList of Parts For Diy Dremel CNC by Nikodem Bartnik: Part Name Quantity Banggoodyogesh parmarNo ratings yet

- Compro Russindo Group Tahun 2018 UpdateDocument44 pagesCompro Russindo Group Tahun 2018 UpdateElyza Farah FadhillahNo ratings yet

- Business Simulation Training Opportunity - V1.0Document15 pagesBusiness Simulation Training Opportunity - V1.0Waqar Shadani100% (1)

- SLE Case Report on 15-Year-Old GirlDocument38 pagesSLE Case Report on 15-Year-Old GirlDiLa NandaRiNo ratings yet

- Tax Q and A 1Document2 pagesTax Q and A 1Marivie UyNo ratings yet

- 2 - How To Create Business ValueDocument16 pages2 - How To Create Business ValueSorin GabrielNo ratings yet

- Organisation Study of KAMCODocument62 pagesOrganisation Study of KAMCORobin Thomas100% (11)