Professional Documents

Culture Documents

9 - Reviews in Gynaecological and Perinatal Practice Volume 6 Issue 3-4 2006 (Doi 10.1016/j.rigapp.2006.04.001) Sarah Vause Stelios Christodoulou - Repeat Caesarean Section or Induction of Labour

Uploaded by

Stefani LarasatiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

9 - Reviews in Gynaecological and Perinatal Practice Volume 6 Issue 3-4 2006 (Doi 10.1016/j.rigapp.2006.04.001) Sarah Vause Stelios Christodoulou - Repeat Caesarean Section or Induction of Labour

Uploaded by

Stefani LarasatiCopyright:

Available Formats

Repeat Caesarean section or induction of labour

Sarah Vause

a,

*

, Stelios Christodoulou

b

a

Department of Obstetrics, St Marys Hospital, Hathersage Road,

Manchester M13 OJH, United Kingdom

b

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Royal Preston Hospital,

Sharoe Green Road, Preston, United Kingdom

Received 21 December 2005; accepted 3 April 2006

Available online 30 May 2006

Abstract

Obstetricians frequently need to decide whether to induce a woman who has previously been delivered by Caesarean section (LSCS).

There is very little evidence from randomised controlled trials to aid their decision making. Observational studies, with their inherent

aws, suggest a 3.6%maternal complication rate in women undergoing repeat elective LSCS, and approximately 66%vaginal delivery rate

and 1% uterine rupture rate in women who were induced. There is little evidence to guide the choice of induction agent. Various factors

have been suggested to predict a successful vaginal delivery, but a previous vaginal delivery appears to be strongly predictive of a good

outcome. Alternative strategies, such as stretching and sweeping the membranes or awaiting spontaneous labour, may reduce the need for

induction. If labour is induced in a woman with a scarred uterus we should ensure that the high risk situation is not compounded by poor

care in labour.

# 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Induction of labour; Vaginal birth after Caesarean section; Uterine rupture

1. The clinical dilemma

What should the obstetrician advise a woman whose

pregnancy has reached 41 weeks gestation? The evidence

suggests that she should be offered induction of labour as

this reduces the risk of perinatal mortality compared with

conservative management [1]. But what should that

obstetrician advise if the woman has previously had a

lower segment Caesarean section? Does the evidence still

apply, or has the balance of risk changed?

The clinician and woman have three options. They may

choose to perform a repeat Caesarean section; or they may

opt for induction by whatever method; or await spontaneous

onset of labour. What does the evidence show?

1.1. Randomised controlled trials of elective repeat

LSCS versus induction of labour

Unfortunately there are no randomised controlled

clinical trials comparing these options in women with a

previous Caesarean section and any comparative data come

from observational studies with all their inherent dis-

advantages.

1.2. Induction of labour versus awaiting spontaneous

labour

There is only one randomised trial of induction of labour

versus awaiting spontaneous labour in women with a

previous LSCS scar [2]. This trial used 200 mg mifepristone

on 2 successive days and showed a signicant increase in the

number of women who laboured within 4 days and a

reduction in oxytocin usage. The trial was too small (n = 32)

to assess maternal or fetal morbidity.

www.elsevier.com/locate/rigapp

Reviews in Gynaecological and Perinatal Practice 6 (2006) 233239

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +44 161 276 6426; fax: +44 161 276 6143.

E-mail addresses: sarah.vause@cmmc.nhs.uk (S. Vause),

stchristodoulou@hotmail.com (S. Christodoulou).

1871-2320/$ see front matter # 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.rigapp.2006.04.001

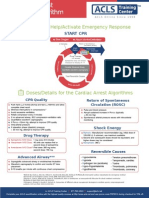

Faced with this lack of evidence from randomised

controlled trials obstetricians have to advise based on the

perceived balance of risks (Fig. 1).

2. What is the morbidity from elective repeat

Caesarean section?

The morbidity from elective repeat Caesarean section is

difcult to assess, as many of the large observational studies

include women who would not be suitable for a trial of

labour or induction of labour [3].

A large (n = 33,699) prospective multicentre observa-

tional study described a 3.6% maternal complication rate in

women undergoing a repeat elective LSCS and compared

this to women having a trial of labour [4]. Another

observational study by McMahon et al. has suggested that

8.4% of women would experience some morbidity (0.8%

major morbidityhysterectomy or operative visceral injury

and 7.6% minor morbiditypyrexia, transfusion or wound

infection) [5]. Rates of complications are detailed in Table 1

with gures for women having trials of labour after previous

LSCS as comparison (not all were induced).

None of the studies have examined the length of

convalescence, a factor likely to be of great importance to

a mother with a small baby who probably has at least one

other child at home.

As the risk of placenta previa, placenta accreta and

hysterectomy increase with the number of repeat LSCS, it

has recently been suggested that the number of future

pregnancies a woman is planning should be taken into

account when making the decision whether to repeat a LSCS

or induce labour [6].

3. What about the morbidity in women with a

previous LSCS who are induced?

The overall rate of morbidity in women with a previous

LSCS who are induced will depend on:

(i) the relative proportions which deliver vaginally or by

LSCS;

(ii) the rate of uterine rupture in the women who are

induced.

3.1. The relative proportions which deliver vaginally or

by LSCS

Obtaining accurate gures from the literature is difcult

because there may be

Reporting bias with authors more willing to report series

where there are high rates of vaginal delivery and low

rates of uterine rupture.

Majority of papers have relatively small numbers of

women.

Dosage regimes vary.

Several different methods of induction can be used in the

same study [710].

The choice of induction agent may be inuenced by

cervical status, the women with a less favourable cervix

receiving prostaglandin and those with the more favour-

able cervix being induced by amniotomy.

Failure to discriminate whether oxytocin is used as an

induction agent or to augment labour [11,12].

Failure to differentiate between women who have and

have not had previous vaginal deliveries [13].

Differences in cultural context [14].

Given above, it is hardly surprising that there is wide

variation in the vaginal delivery rates between studies

which range from 53% to 89% [3,1523]. In a large study

from Switzerland the vaginal delivery rate in a group of

2459 women with a scarred uterus who were induced was

65.6%, compared to a rate of 75.1% in women with a

scarred uterus who laboured spontaneously [3]. In a large

prospective multicentre observational study from the

United States the respective gures were 67% and 80%

[20].

3.2. The rate of uterine rupture in the women who are

induced

It is again difcult to obtain accurate gures from the

literature for the rate of uterine rupture in women who are

S. Vause, S. Christodoulou / Reviews in Gynaecological and Perinatal Practice 6 (2006) 233239 234

Fig. 1. Which carries more risk elective repeat LSCS or induction of

labour?

Table 1

Morbidity in women undergoing an elective repeat LSCS compared with

trial of labour

Elective

repeat

LSCS

Successful

trial of

labour

Failed

trial of

labour

Wound infection (%) [5] 2.2 0 3.3

Pyrexia (%) [5] 6.4 3.5 8.0

Operative visceral

injury (%) [5]

0.6 0.1 3.0

Transfusion (%) [4] 1.0 1.2 3.2

Thromboembolism (%) [4] 0.1 0.02 0.1

Hysterectomy (%) [4] 0.3 0.1 0.5

Maternal death (%) [4] 0.04 0.01 0.04

Mean hospital stay

(days) [6]

5.0 2.3 5.3

induced, for the same reasons outlined in the list above.

Some studies do not differentiate between asymptomatic

dehiscence and symptomatic rupture.

If the results of 14 observational studies [4,15,20,2226]

are pooled a total of 91 ruptures were described in 8841

women with a previous LSCS who were induced (1.0%).

This compares with 75 ruptures in 16,814 women (0.4%) in

these studies who laboured spontaneously. Some of the

studies did not include a spontaneous labour group. These

gures must therefore be interpreted extremely cautiously

bearing in mind the potential problems with the data

described above.

In the largest study (a multicentre prospective cohort

study from the United States) the uterine rupture rate in the

women who were induced was signicantly higher than in

those labouring spontaneously [4]. The uterine rupture rate

in women who were induced (n = 4708) was 1.0%, in those

augmented (n = 6009) was 0.9% and in the spontaneous

labour group (n = 6685) was 0.4%. In the previously quoted

large Swiss study the rate of uterine rupture in the 2459

women who were induced was 0.65% [3].

3.3. Perinatal mortality in women who are induced

In a retrospective population based study, there was no

signicant difference in perinatal mortality between women

with a scarred uterus induced with prostaglandin (3/2398),

and those with a scarred uterus undergoing a trial of labour

who did not have prostaglandins (17/13,120). Overall this

was approximately 11 times greater (odds ratio [OR], 11.6;

95% CI, 1.686.7) than the risk associated with planned

repeat Caesarean delivery (1/9014) [27].

4. How should we induce labour after previous

LSCS?

Many trials comparing different methods of induction of

labour have excluded women with a scarred uterus [28,29].

It may therefore be inappropriate to extrapolate ndings

from these trials to women who have previously been

delivered by LSCS.

There have only been two randomised controlled trials of

different methods of induction in women with previous

LSCS and both were extremely small [30,31].

One trial compared prostaglandin E2 with amniotomy

and oxytocin [30]. There was no signicant difference in

vaginal delivery rates (prostaglandin 17/21 81% versus

ARM and oxytocin 15/21 71%), and one uterine rupture in a

woman in the prostaglandin group who was also augmented

with oxytocin.

Another trial compared misoprostol with amniotomy and

oxytocin was terminated prematurely after only 38 women

had been recruited, when two uterine ruptures occurred in

the group of women treated with misoprostol [31]. The

authors recommended that misoprostol should not be used in

women with a scarred uterus.

As the numbers of women in both of these randomised

controlled trials was small (n = 42 and 38) it is impossible to

draw from them any conclusions as to which method of

induction to use.

No case control studies evaluating the relative risk of scar

rupture with different methods of induction have been

published, and therefore obstetricians can only base their

advice on observational studies.

Several papers describe cohorts of women induced by a

variety of methods after a previous LSCS [810]. However,

the outcomes described for the various methods of induction

could be prone to bias. For example, a woman with a soft

favourable cervix would be more likely to be induced with

amniotomy and oxytocin and go on to deliver vaginally, than

a woman with a long rm closed cervix who may be given

prostaglandin. The two treatment groups may therefore be

dissimilar and it would not be appropriate to compare

outcomes from the two groups.

One frequently cited study exemplies the need for

critical appraisal of the evidence [32]. It appeared to show

that compared with elective repeat LSCS, spontaneous

labour had a relative risk of 3 for uterine rupture, induction

without the use of prostaglandin had a relative risk of 5,

and induction with prostaglandin a relative risk of 16.

However no description was given of cervical status,

dosage regimes, augmentation or vaginal delivery rates.

The data for this study were obtained from computerised

administrative records such as the clinical coding on

hospital discharge summaries, with the authors acknowl-

edging frequent inaccuracies [32]. Unfortunately, the

gures from this paper are quoted in the current NICE

guideline, with no reference being made to the poor

methodology [33].

4.1. Amniotomy and oxytocin for induction after

previous LSCS

A vaginal delivery rate of 72% was achieved in an

observational study n = 32 which is comparable to that

found in the previously mentioned randomised controlled

trial [34]. In these studies no uterine ruptures were

reported in the groups induced with oxytocin. However

Zelop et al. reported nine uterine ruptures (2%) among 458

women in whom labour was induced with oxytocin alone

[35]. Unfortunately, they failed to report vaginal delivery

rates.

4.2. Prostaglandin for induction after previous LSCS

Eight studies have been identied where the use of

prostaglandin to induce women with a previous scar is the

main focus [3643]. In three studies there are no comparison

groups and three studies have fewer than 30 cases. The rates

of vaginal delivery in these studies ranged from 5084%,

S. Vause, S. Christodoulou / Reviews in Gynaecological and Perinatal Practice 6 (2006) 233239 235

with an overall vaginal delivery rate of 63% if the studies are

combined. The overall symptomatic rupture rate if all the

studies were combined was 0.6%.

5. Prostaglandins or poor care?

In the CESDI 5th annual report a focus group examined

the care of 42 women in whom a ruptured uterus was

associated with the death of the baby [44]. A disproportio-

nately large number of these women (18almost half) had

previous LSCSs and had been induced with prostaglandin.

Whilst this may initially raise concerns about the relation-

ship between prostaglandin and scar rupture, examination of

the antenatal and intrapartum care of these women revealed

that in most cases inappropriate decisions had been made or

inappropriate care given. Aspects of care criticised by the

CESDI panel were inadequate recognition of risk, inap-

propriate decisions regarding induction, inappropriate

settings for induction of a woman with a scarred uterus,

lack of involvement of senior staff, inadequate intrapartum

surveillance and lack or recognition of the overall picture as

a high risk situation.

When a woman with a previous LSCS is induced it is

important that there is ongoing recognition of the level of

risk by all members of the clinical team, and whilst we

should think carefully before starting the induction process,

we should also continue to think carefully about when to

stop the process.

6. Can we select women better?

6.1. Predicting vaginal delivery

If it were possible to predict accurately which women

would achieve a vaginal delivery the number of emer-

gency LSCS and their associated morbidity would be

reduced. Predictive features may assist the clinician and

the woman in reaching a decision about whether to

embark on induction.

Using a population of 23,286 women with one prior

LSCS, Smith et al. developed and validated a model for

predicting the risk of delivery by LSCS antenatally [45].

Factors associated with emergency LSCS were maternal

age, maternal height, male fetus, no previous vaginal birth,

prostaglandin induction of labour and birth at or after 41

weeks. Non prostaglandin induction was not predictive of

emergency LSCS. Unlike other studies the risk of Caesarean

section is estimated only using information available in the

antepartum period and therefore can aid counselling in

relation to induction of labour. Other papers have included

variables which are only available when the woman is

admitted in labour, such as cervical status and at this point

the opportunity for elective LSCS has passed and induction

is no longer necessary.

When Smith validated his model he found that 36% of

women had a predicted risk of Caesarean section of less than

20% and their overall Caesarean section rate was 10.9%.

Conversely 16.5% of women had a predicted risk of

Caesarean section of greater than 40% and their overall

Caesarean section rate was 47.7% [45]. However, more than

50% of those predicted to be high risk still achieved a

vaginal delivery.

In women with a previous LSCS who are induced, a

previous vaginal delivery and greater cervical effacement at

commencement of induction appear to positively predict a

successful outcome [25], whilst the need for augmentation is

associated with a poorer outcome [46]. Although the indica-

tion for the previous LSCS appears to predict outcome in

women who labour spontaneously, [47] it does not seem to

be predictive in women who are induced in a subsequent

pregnancy [46]. However, this may reect some degree of

selection bias as women who are considered to have had a

signicant degree of cephalopelvic disproportion previously

may not be considered suitable for induction, and therefore

do no feature in the published series.

In McNally and Turners series 64% of women with an

unfavourable cervix and no previous vaginal delivery were

delivered by LSCS, whilst in women with a previous vaginal

delivery the incidence of a repeat Caesarean section in labour

was only 4% [46]. In a series by Kayani and Alrevic, where

the majority of women were induced with prostaglandin, the

vaginal delivery rate was 44% in women with no previous

vaginal delivery and 83% in women who had delivered

vaginally [20]. In a series by Grinstead and Grobman, where

the majority of women had non prostaglandin inductions,

prior vaginal delivery was independently associated with an

increased chance of vaginal delivery (OR3.795%CI 1.97.1)

[15].

6.2. Predicting uterine rupture

In Smiths model described above the risk of uterine

rupture and the risk of uterine rupture with perinatal death

were associated with an increased predicted risk of

Caesarean section [45]. In women predicted to be at low

risk of LSCS the observed incidence of uterine rupture was

0.2% and in those predicted to be at high risk the incidence

of uterine rupture was 0.9%.

Ultrasonographic measurement of scar thickness has

been proposed as a method of predicting uterine rupture or

scar dehiscence [48]. Whilst it has been found that scar

thickness is inversely related to the frequency of defective

scars, the positive predictive value is low (11.8% for a cut

of value of 3.5 mm). No trials have been done where

women are randomised to either revealing or concealing

the results of scar thickness measurements, and therefore it

is difcult to assess the effect of this intervention on

outcome. One prospective open study with historical

controls showed no change in the overall repeat Caesarean

section rate, but more elective Caesarean sections were

S. Vause, S. Christodoulou / Reviews in Gynaecological and Perinatal Practice 6 (2006) 233239 236

performed with a compensatory reduction in emergency

procedures [49].

Avoidance of overstimulation of the uterine contractions

during induction or augmentation of labour by using

intrauterine pressure monitoring has been suggested as a

way of preventing uterine rupture. However, a series of 10

ruptures has been described in which intrauterine pressure

was monitored [50].

In 6 of the 10 cases scar rupture occurred when the uterine

activity was within normal limits, presumably reecting a

weak scar rather than an overstimulated uterus.

A recent observational cohort study has suggested that

there may be an increased incidence of uterine rupture in

women whose previous uterine incision was closed using a

single-layer technique rather than a double layer closure

[51]. However, other confounding factors may inuence

this, and the current Caesar study will address this issue in

the context of a randomised controlled trial.

7. Are there any alternatives?

As this is obviously a high risk situation to which there

are no easy or evidence based answers, it is worth

considering whether there are ways to reduce the numbers

of women for whom this decision arises.

The recent National Sentinel Caesarean Section Audit

study highlights the numbers of LSCS performed for fetal

distress without scalp pH being done, and the numbers of

LSCS performed for failure to progress without oxytocin

augmentation being used [52]. An active policy of external

cephalic version can reduce the number of LSCS performed

for malpresentation [53]. Minimising the incidence of

primary LSCS minimises the number of women where

decisions about induction or repeat LSCS have to be made in

subsequent pregnancies.

Postmaturity is the most common indication for induction

in women with a previous LSCS [52]. Evidence suggests

that the number of women requiring induction for

postmaturity can be reduced by using ultrasound scanning

to accurately date pregnancies [1].

Stretching and sweeping the membranes has been shown

to increase the number or women labouring spontaneously,

and hence reducing the numbers requiring formal induction

[54]. For every seven women who have a stretch and sweep

one induction is prevented. This is a cheap and easy evidence

based intervention which can be performed in any antenatal

clinic.

In women with a scarred uterus the wisdom of established

interventions should be critically questioned as the balance

of risks may have changed. For example, the evidence shows

that induction of labour beyond 41 weeks gestation reduces

perinatal mortality and has become an established inter-

vention [1]. However, the number needed to treat is large

(NNT = 476) which means that 476 women would need to

be induced to prevent one perinatal death. If 476 women

with a previous LSCS are induced then, based on the above

gures, it is likely that there would be four or ve uterine

ruptures with the possible death of a fetus. Under such

circumstances it appears that the balance is fairly evenly

poised!

8. Conclusion

Patient choice becomes more important when obstetri-

cians are unable to base their counselling on evidence and

very little evidence is available in relation to induction of

labour after previous LSCS.

Further research is needed to compare the alternatives

of elective repeat LSCS, induction of labour and

conservative management. Research is also needed to

determine the most appropriate method of induction in

women with a scarred uterus. However, as outcomes such

as uterine rupture are rare any such trial would need large

numbers.

Until such evidence becomes available we should

actively use interventions to reduce the number of women

in whom these decisions need to be made, and if we do

decide to induce labour should ensure that the high risk

situation is not compounded by poor care in labour.

Practice points

Patient choice becomes more important

when obstetricians are unable to base their

counselling on evidence. Very little evidence

is available in relation to induction of labour

after previous LSCS.

Evidence based interventions to reduce the

incidence of the rst LSCS should be

employed, for example external cephalic

version.

Evidence based interventions to reduce the

need for induction in women with a previous

LSCS should be employed, for example

sweeping the membranes.

Senior involvement and ongoing recogni-

tion of the level of risk are important to

ensure that a high risk situation is not

compounded by poor care in labour.

Research directions

Consideration of a randomised controlled

trial, or case control study of induction of

labour versus await spontaneous labour

versus elective repeat LSCS. The very large

numbers required may be prohibitive.

Consideration of a randomised controlled

trial of different methods of induction in

women with a previous LSCS scar. Again

S. Vause, S. Christodoulou / Reviews in Gynaecological and Perinatal Practice 6 (2006) 233239 237

recruitment of sufcient numbers of women

may make this impractical.

Prospective use of the model suggested by

Smith, and an observational study of how

this inuenced patient choice and outcome.

Comparative observational study of length

of convalescence in women who chose

repeat LSCS versus induction of labour.

References

[1] Crowley P. Interventions for preventing or improving the outcome of

delivery at or beyond term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev )2001;(2).

[2] Lelaidier C, Baton C, Benia JL, Fernandez H, Bourget P, Frydman R.

Mifepristone for labour induction after previous caesarean section.

BJOG 1994;101:5013.

[3] Rageth JC, Juzi C, Grossenbacher H, for the Swiss Working Group of

Obstetric and Gynecologic Institutions. Delivery after previous Cesar-

ean: A risk evaluation. Obstet Gynecol 1999;93:3327.

[4] Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, et al., for the National Institute of

Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units

Network. Maternal and Perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of

labor after prior Cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med 2004;351:25819.

[5] McMahon MJ, Luther ER, Bowes WA, Olshan AF. Comparison of a

trial of labor with an elective second cesarean section. N Engl J Med

1996;335:68995.

[6] Pare E, Quinones J, Macones G. Vaginal birth after caesarean section

versus elective repeat caesarean section: assessment of maternal

downstream health outcomes. BJOG 2006;113:758.

[7] Hibbard JU, Ismail MA, Wang Y, Te C, Karrison T, Ismail MA. Failed

vaginal birth after a cesarean section: How risky is it? 1. Maternal

morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;184:136573.

[8] Sims EJ, Newman RB, Hulsey TC. Vaginal birth after cesarean: to

induce of not to induce. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;184:11224.

[9] Lao TT, Leung FH. Labor induction for planned vaginal delivery in

patients with previous cesarean section. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand

1987;66:4136.

[10] Adair CD, Sanchez-Romos L, Gaudier FL, Kaunitz AM, McDyer DC,

Briones D. Labor induction in patients with previous cesarean section.

Am J Perinat 1995;12:4504.

[11] Ravasia DJ, Wood SL, Pollard JK. Uterine rupture during induced trial

of labor among women with previous cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2000;183:11769.

[12] Leung AS, Farmer RM, Leung EK, Medearis AL, Paul RH. Risk

factors associated with uterine rupture during trial of labor after

cesarean delivery: a case control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993;

168(5):135863.

[13] Sakala EP, Kaye S, Murray RD, Munson LJ. Oxytocin use after

previous Cesarean: Why a higher rate of failed labor trial? Obstet

Gynecol 1990;75:3569.

[14] Cunha M, Bugalho A, Bique C, Bergstrom S. Induction of labor by

vaginal misoprostol in patients with previous cesarean delivery. Acta

Obstet Gynecol Scand 1999;78:6534.

[15] Grinstead J, Grobman WA. Induction of labor after one prior Cesarean:

predictors of vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:5347.

[16] Chattopadhyay SK, Sherbeeni MM, Anokute CC. Planned vaginal

delivery after two previous caesarean sections. BJOG 1994;101:498

500.

[17] Chattopadhyay K, Senfupta BS, Edrees YB, Lambourne A. Vaginal

birth after cesarean section: Management debate. Int J Gynecol Obstet

1988;26:18996.

[18] Del Valle GO, Adair CD, Sanchez-Ramos L, Gaudier FL, McDyer DC,

Delke I. Cervical ripening in women with previous cesarean deliveries.

Int J Obstet Gynecol 1994;47:1721.

[19] Al Suleiman SA, El Yahia AR, Al Najashi S, Rahman J, Rahman MS.

Outcome of labour in patients with a lower segment Caesarean scar. J

Obstet Gynaecol 1989;9:199202.

[20] Kayani SI, Alrevic Z. Uterine rupture after induction of labour in

women with previous caesarean section. BJOG 2005;112:4515.

[21] Landon MB, Leindecker S, Spong CY, Hauth JC, et al., for the

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Mater-

nal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. The MFMU Cesarean Registry:

Factors affecting the success of trial of labor after previous cesarean

delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;193:101623.

[22] Locatelli A, Regalia AL, Ghidini A, Ciriello E, Bif A, Pezzullo JC.

Risks of induction of labour in women with a uterine scar from

previous low transverse caesarean section. BJOG 2004;111:13949.

[23] Chilaka VN, Cole MY, Habayeb OMH, Konje JC. Risk of uterine

rupture following induction of labour in women with a previous

caesarean section in a large UK teaching hospital. J Obstet Gynaecol

2004;24:2645.

[24] McDonagh MS, Osterweil P, Guise JM. The benets and risks of

inducing labour in patients with prior caesarean delivery: a systematic

review. BJOG 2005;112:100715.

[25] Bujold E, Blackwell SC, Hendler I, Berman S, Sorokin Y, Gauthier RJ.

Modied Bishops score and induction of labor in patients with a

previous caesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:16448.

[26] Lin C, Raynor BD. Risk of uterine rupture in labor induction of

patients with prior caesarean section: An inner city hospital experi-

ence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190:14768.

[27] Smith GCS, Pell JP, Cameron AD, Dobbie R. Risk of perinatal death

associated with labor after previous Cesarean delivery in uncompli-

cated term pregnancies. JAMA 2002;287:268490.

[28] Tan BP, Kelly AJ. Intravenous oxytocin alone for induction of labour.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev )2001;(3).

[29] Botha DJ, Howarth GR. Oxytocin and amniotomy for induction of

labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev )2001;(2).

[30] Taylor AVG, Sellers S, Ah-Moye M, MacKenzie IZ. A prospective

random allocation trial to compare vaginal prostaglandin E

2

with

intravenous oxytocin for labour induction in women previously deliv-

ered by caesarean section. J Obstet Gynaecol 1993;12:3336.

[31] Wing DA, Lovett K, Paul RH. Disruption of prior uterine incision

following misoprostol for labor induction in women with previous

cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 1998;91:82830.

[32] Lydon Rochelle M, Holt VL, Easterling TR, Martin DP. Risk of uterine

rupture during labor among women with a prior Cesarean delivery. N

Engl J Med 2001;345:38.

[33] National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Caesarean section. NICE

Clinical Guideline, vol. 13. London: National Institute for Clinical

Excellence; 2004.

[34] Horenstein JM, Phelan JP. Previous cesarean section: the risks and

benets of oxytocin usage in a trial of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1985;151:5649.

[35] Zelop CM, Shipp TD, Repke JT, Cohen A, Caughey AB, Lieberman E.

Uterine rupture during induced or augmented labor in gravid women

with one prior cesarean delivery. AmJ Obstet Gynecol 1999;181:8826.

[36] Yamani TY, Rouzi AA. Induction of labor with vaginal prostaglandin

E

2

in grand multiparous women with one previous cesarean section.

Int J Gyn Obstet 1999;65:2513.

[37] Flamm BL, Anton C, Goings JR, Nerman J. Prostaglandin E

2

for

cervical ripening: a multicenter study of patients with prior cesarean

delivery. Am J Perinat 1997;14:15760.

[38] Blanco JD, Collins M, Willis C, Prien S. Prostaglandin E

2

gel

induction of patients with a prior low transverse cesarean section.

Am J Perinat 1992;9:803.

[39] Goldberger SB, Rosen DJD, Michaeli G, Markow S, Ben-Nun I, Fejgin

MD. The use of PGE

2

for inductionof labor inparturients witha previous

cesarean section scar. Acta Obstet Gynaecol Scand 1989;68:5236.

S. Vause, S. Christodoulou / Reviews in Gynaecological and Perinatal Practice 6 (2006) 233239 238

[40] MacKenzie IZ, Bradley S, Embrey MP. Vaginal prostaglandins and

labour induction for patients previously delivered by Caesarean sec-

tion. BJOG 1984;91:710.

[41] Norman M, Ekman G. Preinductive cervical ripening with prosta-

glandin E

2

in women with one previous cesarean section. Acta Obstet

Gynaecol Scand 1992;71:3515.

[42] Stone JL, Lockwood CJ, Berkowitz G, Alvarez M, Lapinski R,

Valcamonico A, et al. Use of cervical prostaglandin E

2

gel in patients

with previous cesarean section. Am J Perinat 1994;11:30912.

[43] Williams MA, Luthy DA, Zingheim RW, Hickok DE. Preinduction

Prostaglandin E

2

gel prior to induction of labor in women with a

previous Cesarean section. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1995;40:8993.

[44] CESDI, 5th Annual Report, London; 1998, p. 6371

[45] Smith GCS, White IR, Pell JP, Dobbie R. Predicting caesarean section

and uterine rupture among women attempting vaginal birth after one

prior caesarean section. PLoS Med 2005;2(9):e252.

[46] McNally OM, Turner MJ. Induction of labour after one previous

Caesarean section. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 1999;39(4):4259.

[47] Lavin JP, Stephens RJ, Miodovnik M, Barden TP. Vaginal delivery in

patients with a prior Cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol 1982;59:13548.

[48] Rozenberg P, Gofnet F, Phillippe HJ, Nisand I. Ultrasonographic

measurement of lower uterine segment to assess risk of defects of

scarred uterus. Lancet 1996;347:2814.

[49] Rozenberg P, Gofnet F, Phillippe HJ, Nisand I. Thickness of the lower

uterine segment: its inuence in the management of patients with

previous cesarean sections. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol

1999;87:3945.

[50] Beckley S, Gee H, Newton JR. Scar rupture in labour after previous

lower uterine segment caesarean section: the role of uterine activity

measurement. BJOG 1991;98:2659.

[51] Bujold E, Bujold C, Hamilton EF, Harel F, Gauthier RJ. The impact of

single-layer or double-layer closure on uterine rupture. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2002;186:132630.

[52] Thomas J, Paranjothy S. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynae-

cologists Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit. National Sentinel Cae-

sarean Section Audit Report. RCOG Press; 2001

[53] Hofmeyer GJ. External cephalic version for breech presentation at

term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev )2001;(3).

[54] Boulvain M, Stan C, Irion O. Membrane sweeping for induction of

labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev )2001;(2).

S. Vause, S. Christodoulou / Reviews in Gynaecological and Perinatal Practice 6 (2006) 233239 239

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Distillation ApparatusDocument2 pagesDistillation ApparatusStefani LarasatiNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Laporan 1Document2 pagesLaporan 1Stefani LarasatiNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Supermarket CendawanDocument3 pagesSupermarket CendawanStefani LarasatiNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Molecules 18 09933 3Document16 pagesMolecules 18 09933 3Stefani LarasatiNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Supermarket CendawanDocument3 pagesSupermarket CendawanStefani LarasatiNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Absen NeuroDocument6 pagesAbsen NeuroStefani LarasatiNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- GWK / Uluwatu Pura??: (Jumpsuit Polkadot) (Tanktop Pink)Document1 pageGWK / Uluwatu Pura??: (Jumpsuit Polkadot) (Tanktop Pink)Stefani LarasatiNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Molecules 18 09933 3Document16 pagesMolecules 18 09933 3Stefani LarasatiNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shout For Help/Activate Emergency Response: CPR StartDocument2 pagesShout For Help/Activate Emergency Response: CPR StartdavpierNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- Confirm Booking Le Pirate Beach Club Gili Trawangan: Booking Reference NO:LPG1131Document1 pageConfirm Booking Le Pirate Beach Club Gili Trawangan: Booking Reference NO:LPG1131Stefani LarasatiNo ratings yet

- Dapus RKP Kitis 4Document1 pageDapus RKP Kitis 4Stefani LarasatiNo ratings yet

- Up Date in Head Injury ManagementDocument63 pagesUp Date in Head Injury ManagementStefani LarasatiNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Tamba HanDocument3 pagesTamba HanStefani LarasatiNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Journal Reading Tinea CapitisDocument22 pagesJournal Reading Tinea CapitisStefani LarasatiNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Physical Paper +1ANNUALDocument5 pagesPhysical Paper +1ANNUALprabhnoorprimeNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Bio SafetyDocument57 pagesBio SafetySatyaveer SinghNo ratings yet

- Congenital SyphilisDocument28 pagesCongenital SyphilisMeena Koushal100% (4)

- MNT For Sucrase Isomaltase DeficiencyDocument14 pagesMNT For Sucrase Isomaltase DeficiencySarah DresselNo ratings yet

- Ranula: A Review of LiteratureDocument6 pagesRanula: A Review of LiteratureNicco MarantsonNo ratings yet

- Urolithiasis PDFDocument4 pagesUrolithiasis PDFaaaNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 4446 16364 1 PBDocument8 pages4446 16364 1 PBSafira Rosyadatul AissyNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Zbornik Limes Vol 2Document354 pagesZbornik Limes Vol 2Morrigan100% (1)

- Nettle Rash Symptoms, Causes, TreatmentDocument2 pagesNettle Rash Symptoms, Causes, TreatmentArdave Laurente100% (1)

- Important Uses of Neem ExtractDocument3 pagesImportant Uses of Neem ExtractAbdurrahman MustaphaNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Sas 1# - CHNDocument16 pagesSas 1# - CHNZymer Lee Perez AbasoloNo ratings yet

- Hydrocephalus IDocument52 pagesHydrocephalus IVlad Alexandra50% (2)

- Test-11 (Current Affair-2)Document86 pagesTest-11 (Current Affair-2)Pavansaikumar DasariNo ratings yet

- Angina Pectoris: Dr. Naitik D Trivedi & Dr. Upama N. TrivediDocument15 pagesAngina Pectoris: Dr. Naitik D Trivedi & Dr. Upama N. TrivediNaveen KumarNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Pharmacology ReviewerDocument21 pagesPharmacology ReviewerCzairalene QuinzonNo ratings yet

- HSSC Paper PDF (8) - WatermarkDocument15 pagesHSSC Paper PDF (8) - WatermarkJitender TanwarNo ratings yet

- Epstein Barr VirusDocument13 pagesEpstein Barr VirusDianaLorenaNo ratings yet

- JUUL Labs, Inc. Class Action Complaint - January 30, 2019Document384 pagesJUUL Labs, Inc. Class Action Complaint - January 30, 2019Neil MakhijaNo ratings yet

- Vicente vs. Employees' Compensation CommissionDocument7 pagesVicente vs. Employees' Compensation CommissionAlexNo ratings yet

- BPJ Vol 9 No 2 P 827-828Document2 pagesBPJ Vol 9 No 2 P 827-828MayerNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument3 pagesDaftar PustakaAlmira PutriNo ratings yet

- Envis Newsletter April 2014Document16 pagesEnvis Newsletter April 2014Mikel MillerNo ratings yet

- MeningitisDocument21 pagesMeningitisSonya GodwinNo ratings yet

- 5388 Tech ManualDocument198 pages5388 Tech ManualMichal SzymanskiNo ratings yet

- Progestin-Only Injectables: Characteristics and Health BenefitsDocument11 pagesProgestin-Only Injectables: Characteristics and Health BenefitsRazaria DailyneNo ratings yet

- Basics of DentistryDocument65 pagesBasics of DentistryHiba Shah100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Information Bulletin A FMC Mbbs 2021Document27 pagesInformation Bulletin A FMC Mbbs 2021Bidyut Bikash BaruahNo ratings yet

- بنك طب نفسيDocument19 pagesبنك طب نفسيمحمد نادر100% (1)

- FCA (SA) Part I Past PapersDocument72 pagesFCA (SA) Part I Past PapersmatentenNo ratings yet

- Science Magazine, Issue 6657 (August 4, 2023)Document175 pagesScience Magazine, Issue 6657 (August 4, 2023)Kim LevrelNo ratings yet