Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

Uploaded by

astrabrat1741Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

Uploaded by

astrabrat1741Copyright:

Available Formats

CHILDREN IN CRISIS:

GOOD PRACTICES IN

EVALUATING PSYCHOSOCIAL

PROGRAMMING

Joan Duncan, Ph.D. and Laura Arntson, Ph.D., MPH, for

The International Psychosocial Evaluation Committee and

Save the Children Federation, Inc.

With Support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation

" #$$%& '()* +,* -,./01*2 3*0*1(+.42& 5267 8// 1.9,+: 1*:*1)*07

;,4+4 61*0.+:< 8=9,(2 >*=?9** .2 ;(@.:+(2 AB 3(1(, C(2D?(E -,./0 .2 F4G(HA.I?* AB F.6,(*/ J.:6*9/.*E -,./01*2 .2 K/

'(/)(041 AB >*A*66( C(2*:E L1A(2 '+1**+ -,./0 .2 C(@(1+( AB >.6,(10 M410E 8=9,(2 J4B .2 ;(@.:+(2 AB 3(1(, C(2D?(E N.1/

.2 J(:1( AB '()* +,* -,./01*2 '+(==7

Good Practices In Laluating Psychosocial Programming

_______________________________________________________

i

!"#$%&#

In recent years, the deastating consequences o long term and iolent conlicts across the globe hae

generated tremendous interest in the psychosocial eects o complex emergencies on children,

amilies and communities. At the same time, as relie organizations hae deeloped projects to address

these critical issues, there hae been relatiely ew resources aailable to these implementing agencies

on how to measure the eectieness o their work. \hat concepts, methods and tools might be used

to ealuate psychosocial projects implemented during crisis situations low do we know i indiiduals

and communities are beneiting oer the short and long-term rom projects designed to acilitate

emotional healing, social reconciliation, and community building

1he deelopment o outcome and impact measures or psychosocial projects in crisis situations

presents a continual challenge or ield practitioners. 1he arious actors inluencing child

deelopment and psychosocial well-being are diicult to isolate, deine, and quantiy. In addition,

change takes time to eidence itsel, a luxury in any emergency response project. As a result, too oten

project practitioners must take a leap o aith that their projects are haing a measurable and positie

eect on the lies o children, amilies, and communities. \ithout indicators, howeer, practitioners

are let in the position o asserting that projects are helpul` in broad and oten uneriied ways.

1here clearly exists a need to deelop models o impact, share lessons learned, promote cross-

ertilization o strategies, and to build eectie interention practices based on sound measures o

project outcomes and impact.

1o pursue this broad objectie, Sae the Children lederation, Inc. ,Sae the Children USA,, with

support rom the Andrew \. Mellon loundation, initiated a collaboratie process among a number

o academic institutions, donor organizations, and ield-oriented non-goernmental organizations that

are operational in the broad area o psychosocial programming. Persons rom these organizations

with extensie experience in psychosocial programming participated in initial discussions regarding

the ocus o this document. A core committee o iteen members was organized based on these

initial discussions. 1he core committee has been responsible or the oerall conceptualization and

articulation o content area o this manual. In an eort to broaden the programmatic, cultural and

geographic expertise o the core committee, seeral colleagues with extensie experience in

psychosocial programming were asked to proide eedback at arious points throughout the

deelopment o preious drats o this document.

1he manual should be considered a working document.` \e anticipate that, through dissemination

o this document, colleagues, ield-based managers, and coordinators o psychosocial projects can

continue to proide critical reiew and urther input across a ariety o disciplines, cultural settings,

and regional perspecties.

Good Practices In Laluating Psychosocial Programming

_______________________________________________________

ii

Overview

1his manual attempts to articulate major principles o psychosocial project design and ealuation

practices in concise, user-riendly terms. It is intended or ield-based managers and coordinators o

psychosocial programming, as well as or managers o emergency relie programs who may want to

integrate psychosocial programming methods into more traditional relie eorts, such as ood

distribution, construction projects, and medical assistance. 1he manual also seeks to heighten critical

awareness o the cultural and ethical issues associated with psychosocial work. Since psychosocial

projects ary considerably in emphasis, there is much to be learned rom dierent experiences. lence,

the intention o this manual is to stimulate dialogue and the exchange o lessons learned` across

projects, organizations, theoretical perspecties, and ield-based experiences. 1hrough this dialogue,

we hope to help project managers build concepts and methods or planning, implementing, and

ealuating psychosocial projects using clear strategies.

Cbater Ove seres to orient the reader by briely summarizing the concept o psychosocial

deelopment. 1his chapter ocuses on the relationship between psychosocial deelopment and

culture, amily and peer relationships, risk and resiliency. 1he importance o social and cultural actors

in psychosocial deelopment and in working eectiely with children, amilies, and communities is

emphasized. 1he chapter concludes with a discussion o the limitations o an indiidualized approach

to psychosocial healing in complex emergencies and outlines the beneits o including community

members, especially children and adolescents themseles, in deeloping psychosocial interentions.

Cbater 1ro ocuses more speciically on psychosocial programming. It presents a deinition o

psychosocial programming and introduces major concepts and rationales underlying key principles o

sound psychosocial interentions. It oers a conceptual tool or understanding that dierent groups

within a community react dierently to a crisis and discusses the relationship between target group,

project content and project approaches. linally, it encourages the integration o psychosocial

programming principles into other types o relie interentions, such as health or ood distribution, in

an eort to address children`s needs within the context o amily, community and cultural resources.

Cbater. 1bree tbrovgb i address the topic o ealuating psychosocial projects using case examples.

Components essential to the deelopment o a solid ealuation strategy are presented including:

articulating a project logic model, deeloping objecties and indicators, and considering ealuation

design options.

Cbater erev uses a worksheet` ormat to reiew key concepts and to guide the project planner in a

step-wise ashion through the arious stages o project conceptualization and ealuation.

Good Practices In Laluating Psychosocial Programming

_______________________________________________________

iii

(&)*+,-#./#0#*12

1he Committee would like to acknowledge the inaluable contributions o many colleagues and to

express our appreciation to their organizations or supporting this eort.

\e extend a special thank you to: Llizabeth Jareg and Mike \essells whose work in writing the initial

concept paper helped crystallize the committee`s approach to ealuating psychosocial programs, Jan

\illiamson, Kirk lelsman, Gary Kose, Stan Phiri, and John \illiamson who critically reiewed earlier

drats o this document, Jason Schwartzman, our consultant or his work with the subcommittee on

redrating the irst drat o the document, and to Amy \achtel, Marie de la Soudiere, Alastair Ager,

and 1amara Jachimowicz or their work in ield testing the pilot document.

linally, the Committee would like to thank members who also sered on the Second Drat

Subcommittee-Alastair Ager, Neil Boothby, Marie de la Soudiere, Maryanne Loughry, Jason

Schwartzman, and Mike \essells-or their eorts in urther orienting the document toward

implementing organizations.

Our appreciation also goes to those who contributed in arious ways, including \akini Mack-\illiams

who identiied arious additional readings and resources, and many others who proided eedback

during ield-testing or upon reading drats o the document.

3+*1"4561+"2

37%4"8 Joan Duncan, Long Island Uniersity , Consultant to Sae the Children USA

Alastair Ager, Center or International lealth Studies, Queen Margaret Uniersity College, Ldinburgh

Laura Arntson, Sae the Children USA

Paul Bolton, Boston Uniersity School o Public lealth

Neil Boothby, Sae the Children USA , Program on lorced Migration, Columbia Uniersity Mailman

School o Public lealth

Marie de la Soudiere, 1he International Rescue Committee

Jennier Dec McLwan, Long Island Uniersity

Lehnart lalk, Sae the Children Denmark

Llizabeth Jareg, Sae the Children Norway

Maryanne Loughry, Oxord Uniersity Reugee Studies Programme

Jean Claude Legrand, UNICLl

Carlinda Monteiro, Christian Children`s lund, Angola

Mary Anne Schwalbe, \omen`s Commission or Reugee \omen and Children

Amy \achtel, 1he International Rescue Committee

Ronald \aldman, Program on lorced Migration, Columbia Uniersity Mailman School o Public

lealth

Mike \essells, Christian Children`s lund , Randolph-Macon College

Good Practices In Laluating Psychosocial Programming

_______________________________________________________

iv

9%5-# +$ 3+*1#*12

Preace___________________________________________________________________ i

Oeriew _________________________________________________________________ii

Acknowledgements ________________________________________________________ iii

Contributors _____________________________________________________________ iii

37%:1#" ;8 3+0:-#< =0#"/#*&4#2 %*. !2>&7+2+&4%- ?#@#-+:0#*1 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA;

BC B*1"+.6&14+* AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA;

B*2#1 ;8 3+*@#*14+* +* 17# D4/712 +$ 17# 374-.AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA E

BBC 97# F##. $+" B*1#"@#*14+*AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA G

B*2#1 E8 97# B0:%&1 +$ 3+0:-#< =0#"/#*&4#2 +* B*.4@4.6%-2 H

3+006*414#2 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA G

B*2#1 G8 97# 3+*1#<1 +$ B*1#"@#*14+* AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA I

B*2#1 I8 (22#224*/ !2>&7+2+&4%- B0:%&12 %*. D#2:+*.4*/

!"+/"%00%14&%--> AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA J

BBBC !2>&7+2+&4%- ?#@#-+:0#*1 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA K

A. Social and Cultural Nature o Child Deelopment _______________________________ 6

B*2#1 J8 97# L+&4%- =&+-+/> 4* M74&7 374-."#* ?#@#-+:AAAAAAAAAAAAAAA K

?4%/"%0 ;C L+&4%- =&+-+/> +$ 17# 374-.AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA N

B. Psychosocial Deelopment Deined__________________________________________

B*2#1 K8 97# D+-# +$ 17# L+&4%- M+"-. 4* B*.4@4.6%- ?#@#-+:0#*1 AAAAAAA N

?4%/"%0 EC 97# L+&4%- M+"-. 4* B*.4@4.6%- ?#@#-+:0#*1 AAAAAAAAAAAAA O

C. Cross-Cultural Commonality and Diersity ____________________________________ 9

D. Resiliency and Protectie lactors ___________________________________________10

B*2#1 N8 L+0# 37%"%&1#"4214&2 +$ D#24-4#*1 374-."#* AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA;P

B*2#1 O8 !"+1#&14@# Q%&1+"2 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA;P

B*2#1 R8 D#24-4#*&> %*. !"+1#&14@# Q%&1+"28 S#22+*2 S#%"*#. AAAAAAAAAAA ;;

B*2#1 ;P8 L+0# 37%"%&1#"4214&2 +$ D#24-4#*1 3+006*414#2 AAAAAAAAAAAAAA;E

L. Children`s Reactions to Violence ____________________________________________12

B*2#1 ;;8 D42) Q%&1+"2 4* T4+-#*1 34"&6021%*AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA;E

B*2#1 ;E8 374-."#*U2 D#%&14+*2 1+ T4+-#*&# AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA;G

BTC 3+*&#:16%- (.@%* 4* !2>&7+2+&4%- ?#@#-+:0#*1 H 3+0:-#< =0#"/#*&4#2AAAAA;I

A. Limitations o Indiidualized Approaches _____________________________________14

B. Moing rom Indiiduals to Communities _____________________________________15

37%:1#" V*# L600%"> AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA;K

37%:1#" E8 M7%1 B2 !2>&7+2+&4%- !"+/"%004*/W AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA;N

BC ?#$4*414+* AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA;N

B*2#1 ;G8 Q6*.%0#*1%- X+%-2 +$ !2>&7+2+&4%- !"+/"%004*/ AAAAAAAAAAA;N

BBC ?40#*24+*2 +$ !2>&7+2+&4%- !"+/"%004*/AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA;O

A. 1arget Population _______________________________________________________18

?4%/"%0 G8 X"+6:2 ,4174* % 3+006*41> ?4$$#"#*14%1#. (&&+".4*/ 1+

!2>&7+2+&4%- B0:%&1 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA;R

B. Project Content _________________________________________________________19

Good Practices In Laluating Psychosocial Programming

_______________________________________________________

v

B*2#1 ;I8 L1"#*/17#*4*/ B*.4@4.6%-2 %*. L+&4%- =*@4"+*0#*12 1+ L6::+"1

!2>&7+2+&4%- ?#@#-+:0#*1 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAEP

B*2#1 ;J8 3+006*41> B*1#/"%14+* %*. 17# D#21+"%14+* +$ 9"621 AAAAAAAAAEP

C. Project Approach________________________________________________________20

B*2#1 ;K8 D#&+00#*.#. !"4*&4:-#2 $+" 9%"/#14*/ !2>&7+2+&4%- !"+Y#&12AAEE

BBBC !2>&7+2+&4%- !"+/"%004*/8 Z%Y+" !"+Y#&1 ("#%2 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAEE

A. 1he Primacy o lamily ___________________________________________________22

B*2#1 ;N8 B*2141614+*%- 3%"# [ F+1 %* (::"+:"4%1# +" S+*/\9#"0 L+-614+* EG

B. Lducation _____________________________________________________________23

C. Lconomic Security_______________________________________________________24

D. Lngaging Actiities ______________________________________________________24

L. Community and Cultural Connections________________________________________24

l. Reconciliation and Restoration o Justice ______________________________________25

37%:1#" 9,+ L600%"> AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAEK

37%:1#" G8 =@%-6%14*/ !2>&7+2+&4%- !"+Y#&128 V@#"%"&74*/ !"4*&4:-#2 %*. !"+Y#&1 S+/4&

Z+.#-2 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAEN

BC M7> B2 =@%-6%14+* B0:+"1%*1 \ =@#* 4* 3+0:-#< =0#"/#*&4#2W AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAEN

B*2#1 ;O8 97# F##. $+" 36-16"%- L#*2414@41> 4* !"+/"%004*/AAAAAAAAAAAAEO

BBC Q+6" V@#"%"&74*/ !"4*&4:-#2 +$ =@%-6%14*/ !2>&7+2+&4%- !"+Y#&12 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAEO

BBBC !"+Y#&1 ]S+/4& Z+.#-2^ AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAGP

B*2#1 ;R8 ( !"+Y#&1 S+/4& Z+.#- AAAAAAAAAAAAA Lrror! Bookmark not deined.

A. Proince-Based \ar 1rauma 1eam__________________________________________31

?4%/"%0 I8 B*414%- !_M99 !"+Y#&1 S+/4& Z+.#- AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAGE

?4%/"%0 J8 D#@42#. !_M99 !"+Y#&1 S+/4& Z+.#- AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAGI

B. Consolacao Lnrichment Project_____________________________________________34

?4%/"%0 K8 3+*2+-%&`+ =*"4&70#*1 !"+Y#&1 S+/4& Z+.#- AAAAAAAAAAAAAGJ

BTC ?#$4*4*/ a#> 9#"02 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAGK

A. Input _________________________________________________________________36

B. Output________________________________________________________________36

C. Outcome ______________________________________________________________36

D. Impact________________________________________________________________3

37%:1#" 97"## L600%">AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAGN

37%:1#" I8 Q6*.%0#*1%- X+%-2 +$ !2>&7+2+&4%- !"+/"%004*/ %*. ?#$4*4*/ V5Y#&14@#2

%*. B*.4&%1+"2 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAGO

BC Q6*.%0#*1%- X+%-2 +$ !2>&7+2+&4%- !"+/"%004*/ AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAGO

BBC ?#$4*4*/ !"+Y#&1 V5Y#&14@#2 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAGR

A. SMAR1` Objecties ____________________________________________________39

B. Making Objecties SMAR1er ______________________________________________40

B*2#1 EP8 V5Y#&14@#2 +$ 17# 3+*2+-%&`+ =*"4&70#*1 !"+Y#&1 AAAAAAAAAAAAI;

BBBC B.#*14$>4*/ B*.4&%1+"2AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAI;

A. Quantitatie and Qualitatie Indicators _______________________________________44

BTC S4*)4*/ V5Y#&14@#2 %*. B*.4&%1+"2 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAII

Good Practices In Laluating Psychosocial Programming

_______________________________________________________

vi

?4%/"%0 N8 S4*)4*/ !"+Y#&1 B*:612b V61:612b V5Y#&14@#2b %*. 17#4"

B*.4&%1+"2 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAIJ

B*2#1 E;8 V5Y#&14@#2 %*. B*.4&%1+"2 $+" c+:#$6-*#22 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAIN

TC d24*/ B*.4&%1+"2 1+ Z+*41+" !"+Y#&1 B*:61 %*. V61:61 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAIN

A. Consolacao Lnrichment Project ____________________________________________48

B. Sample Input,Output Matrix_______________________________________________49

9%5-# ;8 Z+*41+"4*/ B0:-#0#*1%14+*8 S4*)4*/ B*:61b V61:61b B*.4&%1+"2b %*.

?%1% L+6" AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAIR

TBC =@%-6%14*/ !"+Y#&1 V61&+0# AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAJP

A. 1he Dierence between Project Outcome and Impact ___________________________51

?4%/"%0 OAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAJE

B. Indicators as Measures o Status or Outcome __________________________________52

B*2#1 EE8 =%21 940+"8 e6%-41%14@# V61&+0# B*.4&%1+"2 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAJG

C. An Laluation Matrix: Objecties, Outcomes, Indicators, and Data Sources __________53

9%5-# E8 =@%-6%14+* Z%1"4<8 V5Y#&14@#2b V61&+0#2b B*.4&%1+"2b %*. ?%1%

L+6" AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAJI

D. Proxy Indicators________________________________________________________55

37%:1#" Q+6" L600%">AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAJK

37%:1#" J8 B.#*14$>4*/ ?%1% L+6" %*. Z#17+.2 +$ ?%1% 3+--#&14+*AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAJN

BC ?%1% L+6"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAJN

9%5-# G8 =<%0:-# ?%1% L+6" $+" Q6*.%0#*1%- X+%-2 +$ !2>&7+2+&4%-

!"+Y#&12AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAJN

A. Qualitatie Data Sources o Consolacao Lnrichment Project ,CLP, _________________59

B*2#1 EG8 3+*2+-%&`+ =*"4&70#*1 !"+Y#&18 (55"#@4%1#. L&"##*4*/

Z#%26"# AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAJR

B*2#1 EI8 e6%-41%14@# Z#17+.2 +$ 17# 3+*2+-%&`+ =*"4&70#*1 !"+Y#&1 AAAAKP

BBC Z#17+.2 +$ ?%1% 3+--#&14+*AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAKP

A. Open-ended Interiews and locus Group Interiews ____________________________60

B. Lthnographic 1echniques _________________________________________________63

C. Direct Obseration 1echniques _____________________________________________64

D. Back-1ranslation o Scales ________________________________________________65

L. 1riangulation ___________________________________________________________65

37%:1#" Q4@# L600%"> AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAKK

37%:1#" K8 !"+Y#&1 B0:%&1 =@%-6%14+* AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAKN

BC B0:%&1 =@%-6%14+* AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAKN

A. Attributing Outcome_____________________________________________________68

B*2#1 EJ8 (11"45614*/ V61&+0# 1+ % L:#&4$4& B*1#"@#*14+* AAAAAAAAAAAAAAKO

B. Reasonable Assurance o Project Impact _____________________________________69

BBC D#2#%"&7 ?#24/* V:14+*2 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAKR

A. Major 1ypes o Comparison Groups _________________________________________0

BBBC =@%-6%14+* ?#24/*2 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAN;

A. Partial Coerage Projects __________________________________________________2

B. lull Coerage Projects ____________________________________________________3

Good Practices In Laluating Psychosocial Programming

_______________________________________________________

vii

BTC L%0:-4*/ AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAANI

A. Probability Sampling _____________________________________________________5

B. Nonprobability Sampling__________________________________________________6

TC Z+"# +* e6%-41%14@# ?%1% 3+--#&14+* %*. (*%->242 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAANN

37%:1#" L4< L600%"> AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAANN

37%:1#" N8 ?#24/*4*/ % !2>&7+2+&4%- !"+Y#&1 %*. _64-.4*/ %* =@%-6%14+* L1"%1#/> AAAAAAANO

BC a#> e6#214+*2 4* Q+"06-%14*/ % !2>&7+2+&4%- !"+Y#&1 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAANO

BBC ?#@#-+: % ]S+/4& Z+.#-^ AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAOE

BBBC ]LZ(D9^ V5Y#&14@#2 %*. Z#%26"%5-# V61&+0#2 AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAOK

BTC ?#@#-+: B*.4&%1+"2 1+ Z#%26"# (&74#@#0#*1AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAON

TC ?#24/* % L1"%1#/> 1+ Z+*41+" !"+Y#&1 B*:61 %*. V61:61AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAARP

TBC V61&+0# %*. B0:%&1 =@%-6%14+*2AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAARG

A. Outcome Laluation _____________________________________________________93

B. Impact Laluation ______________________________________________________98

C. Reporting ____________________________________________________________103

D. Next Steps ___________________________________________________________104

L=S=39=? D=LVdD3=L AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA;PK

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

1

37%:1#" V*#

37%:1#" ;8 3+0:-#< =0#"/#*&4#2 %*. !2>&7+2+&4%- ?#@#-+:0#*1

1bi. cbater re.evt. a ai.cv..iov of .,cbo.ociat aeretovevt a. it i. ivftvevcea b, cvttvre, favit, ava eer retatiov.bi.,

ri./ ava re.itievc,. 1be ivortavce of .ociat ava cvttvrat factor. iv .,cbo.ociat aeretovevt ava iv ror/ivg effectiret,

ritb cbitarev, favitie., ava covvvvitie. i. evba.iea. 1be cbater .tre..e. tbat covte evergevcie. ai.rvt

ivairiavat, favit,, ava covvvvit, fvvctiovivg ava ai.cv..e. .ove of tbe tivitatiov. of av ivairiavatiea aroacb to

.,cbo.ociat rogravvivg. 1be veea to ev.vre covvvvit, articiatiov iv ro;ect tavvivg, ivtevevtatiov, ava

eratvatiov i. ai.cv..ea.

BC B*1"+.6&14+*

In many parts o the world, war, epidemics, natural disasters, and other humanitarian crises hae

resulted in complex emergencies

1

causing wide-ranging, multiaceted, sustained negatie impact on

children, amilies, and communities. Such emergencies impose heay emotional, social, and spiritual

burdens on children and their amilies that are associated with death, separation and loss o parents and

caregiers, disruption o organized patterns o liing and meaning, attack and ictimization, destruction

o homes, and economic ruin. In these situations, children`s deelopment is disrupted, security and trust

in humankind threatened, and a sense o hope or the uture undermined.

Goernmental and nongoernmental organizations across the world hae grown in their understanding

o appropriate response to such circumstances. 1he United Nations Children`s lund ,UNICLl,, or

example, was created in the atermath o the Second \orld \ar. Reichenberg and lriedman

2

,1996,, in

their examination o the eolution o this organization`s approach to working with war-aected

children, amilies, and communities, create a historical ramework that anchors current day psychosocial

programming and strategies. \hile UNICLl originally and primarily ocused on short-term material

assistance through the distribution o ood, clothing, and medicine, the organization increasingly

realized that projects needed to be longer-term and to consider the whole child within the context o his

or her community and culture i the desired beneits were to be obtained.

Adopted in 1989, the Conention on the Rights o the Child ,CRC, established a legal and ethical

ramework to guide the international community in working with children during times o stability as

well as during emergencies. Conention articles address, or example, amily separation and

reuniication eorts and the protection and care o children aected by armed conlict ,see Inset 1,.

Collectiely, the articles establish an interention standard that encompasses, as stated in Article 39,

measures to promote physical and psychological recoery and social re-integration o a child.` in

the atermath o complex emergencies.

1

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees defines a complex emergency as a humanitarian crisis in a

country, region, or society where there is a total or considerable breakdown of authority caused by international or

external conflict, which requires an international response that goes beyond the mandate of any single agency and/or

the ongoing United Nations country program.

2

D. Reichenberg and S. Friedman, Traumatized Children: Healing the invisible wounds of children in war: A rights

approach. In International Responses to Traumatic Stress, edited by Yael Danieli, Nigel S. Rodley, & Lars Weisaeth

(New York: Baywood Publishing Company, 1996), 307 326.

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

2

B*2#1 ;8 3+*@#*14+* +* 17# D4/712 +$ 17# 374-.

1he ollowing are articles most releant to complex emergencies.

3

("14&-# R8 Parties shall ensure that a child shall not be separated rom his or her parents against their will, except when

competent authorities subject to judicial reiew determine, in accordance with applicable law and procedures, that such

separation is necessary or the best interests o the child.

("14&-# ;P8 .Applications by a child or his or her parents to enter or leae a State Party or the purpose o amily

reuniication shall be dealt with by States Parties in a positie, humane and expeditious manner. States Parties shall

urther ensure that the submission o such a request shall entail no aderse consequences or the applicants and or the

members o their amily.

("14&-# ;R8 Parties shall take all appropriate legislatie, administratie, social and educational measures to protect the

child rom all orms o physical or mental iolence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or

exploitation, including sexual abuse, while in the care o parent,s,, legal guardian,s, or any other person who has the care

o the child.

("14&-# EP8 A child temporarily or permanently depried o his or her amily enironment. shall be entitled to special

protection and assistance...

("14&-# EE8 Parties shall take appropriate measures to ensure that a child who is seeking reugee status or who is

considered a reugee in accordance with applicable international or domestic law and procedures shall, whether

unaccompanied or accompanied by his or her parents or by any other person, receie appropriate protection and

humanitarian assistance in the enjoyment o applicable rights set orth in the present Conention and in other

international human rights or humanitarian instruments to which the said States are Parties.

lor this purpose, States Parties shall proide, as they consider appropriate, co-operation in any eorts by the United

Nations and other competent intergoernmental organizations or non-goernmental organizations co-operating with the

United Nations to protect and assist such a child and to trace the parents or other members o the amily o any reugee

child in order to obtain inormation necessary or reuniication with his or her amily. In cases where no parents or other

members o the amily can be ound, the child shall be accorded the same protection as any other child permanently or

temporarily depried o his or her amily enironment or any reason, as set orth in the present Conention.

("14&-# EO8 Parties recognize the right o the child to education, and with a iew to achieing this right progressiely and

on the basis o equal opportunity...

("14&-# GI8 Parties undertake to protect the child rom all orms o sexual exploitation and sexual abuse...

("14&-# GO8 Parties shall take all easible measures to ensure that persons who hae not attained the age o iteen years

do not take a direct part in hostilities...

In accordance with their obligations under international humanitarian law to protect the ciilian population in armed

conlict, State Parties shall take all easible measures to ensure protection and care o children who are aectedby an

armed conlict.

("14&-# GR8 Parties shall take all appropriate measures to promote physical and psychological recoery and social

reintegration o a child ictim o: any orm o neglect, exploitation, or abuse, torture or any other orm o cruel,

inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, or armed conlicts. Such recoery and reintegration shall take place in

an enironment that osters the health, sel-respect, and dignity o the child.

Consistent with the CRC, many international and national goernmental and nongoernmental

organizations now consider the psychological and social aspects o humanitarian assistance to children

3

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Convention on the Rights of the Child,

http://www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/k2crc.htm.

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

3

and their amilies as necessary components in responding to the oerall deelopmental needs o

children in complex emergency situations. 1he undamental aim o psychosocial programming is to

improe children`s well-being by:

D#21+"4*/ 17# *+"0%- $-+, +$ .#@#-+:0#*1f

!"+1#&14*/ &74-."#* $"+0 17# %&&606-%14+* +$ .421"#22$6- %*. 7%"0$6- #@#*12f

=*7%*&4*/ 17# &%:%&41> +$ $%04-4#2 1+ &%"# $+" 17#4" &74-."#*f %*.

=*%5-4*/ &74-."#* 1+ 5# %&14@# %/#*12 4* "#564-.4*/ &+006*414#2 %*. 4* %&16%-4g4*/

:+2414@# $616"#2C

As parents,caregiers, communities, goernments, nongoernmental organizations, and donors hae

recognized the importance o addressing the psychological and social needs o children and their

amilies, there has been an increased desire to make aailable the programming concepts and tools

that support this work. Key questions include, low do we conceptualize the psychosocial needs o

children` low do we understand the impact o complex emergencies on amilies and

communities` \hat are key components o psychosocial interentions` and low do we know i

interentions are eectiely addressing these needs` 1here is little inormation aailable on the long-

term consequences o the multiple and continuous eects o war and other complex emergencies on

children, amilies, and communities - especially in the context o poerty and displacement. Gien the

lack o research in this area, this manual is an attempt to put orth one perspectie o responding to

children`s needs in crisis situations based on the contributors` ield and academic experience. 1his

manual begins by proiding a brie orientation to psychosocial deelopment. Key project

interentions are outlined, emphasizing ethical, cultural, and social issues associated with this kind o

work. 1he main ocus o this manual is on measuring the eectieness o psychosocial projects and

proiding practitioners with tools and a ramework or the monitoring and ealuation process.

BBC 97# F##. $+" B*1#"@#*14+*

B*2#1 E8 97# B0:%&1 +$ 3+0:-#< =0#"/#*&4#2 +* B*.4@4.6%-2 H 3+006*414#2

In 1988 our team at larard Uniersity, with the support o the \orld lederation or Mental lealth, sent a psychiatric

team to Site 2, the largest Cambodian reugee camp on the 1hai-Cambodian border. \e interiewed 993 camp residents,

who recounted a total o 15,000 distinct traumatic eents, such as kidnapping, imprisonment, torture, and rape. \et the

international authorities charged with protecting and proiding or the camp had made no proisions whatsoeer or

mental health serices. Similar lapses aected other reugee operations the world oer. Oer time the reason became

clear: the mental health eects o mass iolence are inisible. Put simply, it is easier to count dead bodies and lost limbs

than shattered minds. 1he bottom line is that although only a small percentage o suriors o mass iolence suer

serious mental illness requiring acute psychiatric care, the ast majority experience low-grade but long-lasting mental

health problems. lor a society to recoer eectiely, this majority cannot be oerlooked. Perasie physical exhaustion,

hatred, and lack o trust can persist long ater the war ends. Like chronic diseases such as malaria, mental illness can

weigh down the economic deelopment o a country.

4

1he social abric that binds indiiduals can and does unrael during times o conlict. \hile the

degree o deastation wrought and its ultimate eect on indiiduals aries, children and amilies will

always work to rebuild their lies to surie, endure, and lourish. 1he way people eel, the way they

react to the world, and the way they relate to one another are tremendously inluenced by the series o

crises they hae endured. As Inset 2 illustrates, mental health serices are as critical and lie-saing as

other emergency interentions. \hen rebuilding communities, the eects o extreme horror, ear,

4

R. Mollica, Invisible Wounds, Scientific American 2000: 46.

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

4

mistrust, rage, and engence experienced by most community members, including children, cannot be

ignored any more than the eects o amine, epidemics, and homelessness.

B*2#1 G8 97# 3+*1#<1 +$ B*1#"@#*14+*

lollowing centuries o \estern Colonial domination, Last 1imorese hae lied the past 24 years in a climate o

perpetual ear characterized by systematic oppression by the Indonesian Goernment. One o the century`s worst

genocides took place at the time o the Indonesian take-oer o Last 1imor. An estimated 200,000 people were

massacred or allowed to die o staration. Violent repression, demonstrated by the repeated arrest, torture, and

disappearance o people inoled or thought to be inoled in the liberation struggle, continued throughout the period.

1hese 24 years o repression culminated in the recent crisis ollowing the August 30, 1999 reerendum. On a large scale,

people experienced the burning o homes and towns, attacks on themseles and their amilies, light in the ace o armed

assaults by militias, orced displacement, destruction o businesses, and loss o agricultural means and production. As

people led or were orcibly displaced, large numbers were separated rom each other, and many children were separated

rom their amilies. Many people led to the mountains. Others were orced by militias into \est 1imor, where they

lied in orced exile and constant ear, or were deported to more distant islands, their whereabouts unknown. Large

numbers o people hae disappeared and remain unaccounted or. Nearly eery amily lies with uncertainties about the

location and saety o one or more amily members.

1he returning population ound their land deastated, property looted, homes burned, liestock stolen or killed, and

inrastructure, including schools, destroyed. lousing deastation has been particularly seere, nearly 80 o all homes

were destroyed or damaged.

As people returned home, tensions and outbreaks o iolence hae increased in returnee communities. Returnees rom

\est 1imor include pro-integrationist adults and adolescents-a sub-set o whom had participated in militia-promoted

iolence. 1hus there was an urgent need to address the immediate care and protection needs o children, amilies, and

youth and to promote tolerance, restraint, and reconciliation eorts in returnee communities.

5

A child`s well-being and healthy deelopment require strong and responsie social support systems,

rom the amily to the societal leels. lor example, the illness or death o a child`s caretaker denies the

child the many deelopmental beneits o parenting. Similarly, children who are drien into armed

banditry and crime by circumstances o extreme poerty may contribute to political or ethnic turmoil

in the wider society. In contexts where children's lies are already threatened by malnutrition and ill

health, the eruption o war prookes generational cycles o poerty, iolence, and insecurity.

1he social consequences o iolence can be ound at the community leel in terms o its relatie

cohesion or disintegration. Violence aects eery aspect o social lie, traditional community

structures are broken down, authority igures are weakened, cultural norms and coping mechanisms

are disintegrated, relationships and networks, which traditionally proide support during crises, are

destroyed. As a result, traditional coping mechanisms may disappear. As iolence increases, distrust

and isolation out o ear may become the norm, making children more ulnerable to psychosocial

harm. Psychosocial interentions may operate at the dual leels o ocusing on indiidual health as

well as community reconciliation and peace-building. In act, breaking the cycle o iolence is one

undamental aim o such projects.

In emergency situations, the rights o children are continually iolated, ignored, and unulilled. 1he

objecties o psychosocial interentions, whether in the context o a stand-alone project speciically

aimed at improing the psychosocial well-being o children, or in the context o more traditional

5

Child Protection and Psychosocial Programs Consortium, Care and Protection of Children, Youth and Families in

East Timor. Proposal submitted to the U.S. State Department, Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (2000).

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

5

health, education or other deelopment project, should it within a human rights ramework as

deined by the United Nations ,UN, Conention on the Rights o the Child.

lield experience has shown that it is desirable to take a holistic approach to humanitarian eorts such

that the psychological and social deelopment and needs o children are an integrated part o

programming rom the outset o an emergency situation. As described in Inset 3, the context o

emerency programming is complex and multi-layered. 1he concept o psychosocial recoery is an

attempt to describe a process o coming to terms with the wide range o emotionally traumatic eents,

losses, isolation, destruction o social norms and codes o behaior most children will ace in

emergency situations. Lach indiidual child goes through this process in his or her own unique way

depending on multiple actors, including the nature o the child`s amily enironment, peer

relationships, age, experiences and amily and peer group reactions. It is the position here that

addressing these actors as part o a relie project enhances the oerall eectieness o the project and

also promotes the psychosocial recoery process. lor example, the identiication o women-headed

households and their registration or ood rations can preent women haing to render sexual serices

to be able to eed their children. Consultations with women and children on their special needs or

saety can inluence the placing o water supplies, lighting in the camps, locks or doors, and many

other issues.

B*2#1 I8 (22#224*/ !2>&7+2+&4%- B0:%&12 %*. D#2:+*.4*/ !"+/"%00%14&%-->

1he prolonged repression and terror, coupled with the recent outburst o iolence and loss, hae had proound eects

on the Last 1imorese population, particularly children and adolescents. 1he damaging consequences are dierse and are

both social and psychological. Socially prominent are changes in attitudes and belies, including entrenched hatred or

the other` and loss o trust. Psychologically, many children hae experienced multiple losses, ear, hopelessness, and a

diminished sense o sel-worth and competence. Lidence rom situation analyses indicates that signiicant numbers o

children were experiencing problems such as nightmares, concentration loss, and social isolation. 1he oerall impact is

disruption o normal deelopment.

1o rebuild education and to enable healthy deelopment, it is ital to promote healing, social integration, and recoery.

An essential irst step is to proide structured actiities that normalize lie, aid emotional and social integration, and

reduce the current idleness o many children and youth. Properly designed, these actiities enable the recoery o most

children, although a small number o seerely traumatized children will need special assistance. 1he actiities take place

in sae spaces where parents can participate, support each other, and engage in planning around meeting children`s

needs. Conducted communally, these actiities can help to rebuild the social trust, protection, and tolerance that had

been badly damaged by the recent eents. In addition, structured actiities can proide positie engagement o youth

who hae lied through disturbing and conusing eents, seen amilies and communities torn apart by suspicion and

iolence, and missed important educational opportunities. \outh are signiicant actors who can contribute either to

peace or to continued iolence. Structured actiities promote youth leadership and engage them in proiding assistance

to younger children.

6

Since complex emergencies hae multiple eects on children and communities, it is useul to draw

rom psychological and social theories that hae linked the deelopment o children to the wider

social circles that surround them-their amily, community, and culture. An understanding o the

psychosocial deelopment o children, and interentions that are designed to support this

deelopment, is intertwined with broader concepts o child deelopment. \e turn to these concepts

next.

6

Ibid.

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

6

BBBC !2>&7+2+&4%- ?#@#-+:0#*1

(C L+&4%- %*. 36-16"%- F%16"# +$ 374-. ?#@#-+:0#*1

Children`s deelopment is inextricably connected to the social and cultural inluences that surround

them, particularly the amilies and communities that are children`s lie-support systems.` In all

societies, amilies try to protect and meet the basic needs o children. Beyond the amily, children`s

deelopment is inluenced by interaction with peers, teachers, community members, and, increasingly

throughout the world, by mass media. 1hrough social interaction, children acquire gender and ethnic

identities and internalize culturally constructed norms, alues, and belies, including modes o

expressing emotion and acceptable social behaior. Children usually participate in ormal or non-

ormal education and other social institutions, and learn to become unctional members o their

societies. Children`s deelopment must be considered holistically in order to include this process o

social integration and o becoming connected within their wider social world.

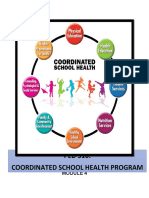

B*2#1 J8 97# L+&4%- =&+-+/> 4* M74&7 374-."#* ?#@#-+:

A social and cultural approach to child deelopment emphasizes the importance o the wider social context that

surrounds us all. 1hese social or ecological` approaches ocus not on the indiidual child but rather on the child

interacting with the nested social systems o amily ,including clan and kinship group, and wider society ,including

community institutions, and potentially, religious and ethnic networks,. A child`s well-being and healthy deelopment

require strong and responsie social support systems, rom the amily to the societal leels.

1his has been represented

graphically in Diagram 1.

7

Adapted from Bronfenbrenner, as cited in: Donahue-Colletta, Understanding Cross-Cultural Child Development and

Designing Programs For Children (PACT, 1992).

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

7

B. Psychosocial Development Defined

Most broadly, psychosocial deelopment o children is deined as the gradual psychological and social

changes that children make as they mature. Psychosocial deelopment consists o the .,cbotogicat

aspects o human deelopment - the capacity to perceie, analyze and learn rom experiences,

understand onesel and others, and experience emotion and .ociat aeretovevt - the ability to orm

attachments, especially to caregiers and peers, maintain satisying reciprocal social relationships, and

to learn and ollow the social codes o behaior o one`s own culture.

1he term psychosocial` implies a ery close relationship between psychological and social actors. \hen

applied to child deelopment, the term underlines the cto.e, ovgoivg covvectiov. between a child`s eelings,

thoughts, perceptions and understanding, and the deelopment o that child as a .ociat being in interaction

with his or her social enironment. Put slightly dierently, psychosocial deelopment is inluenced

throughout childhood by the dynamic interplay o the child`s personality, genetic make-up, and

enironmental actors.

B*2#1 K8 97# D+-# +$ 17# L+&4%- M+"-. 4* B*.4@4.6%- ?#@#-+:0#*1

1he child`s deeloping understanding o the world is shaped by his or her own indiidual experience, as well as by

experience that is shaped and interpreted ,or mediated`, by the amily and broader social and community institutions.

\hen interacting with the world, much o what one learns as a child is not simply trial and error.` Parents, uncles,

grandmothers, siblings, riends, neighbors, school, church, mosque, or temple all likely play a part in making sense` o

the world -oering rules, ideas, explanations, and principles to guide behaior. In this sense the process o growing

up` is ery much a social process because we assimilate the understandings shared and interpreted to us by these aried

inluential igures and institutions. 1he role o the social world in indiidual deelopment can also be represented

graphically, as portrayed in Diagram 2 ,below,.

Child

Risk

Factors

Social

Emotional

Development

Cognitive & Language

Development

Physical

Development

Protective

Factors

Culture/Society

Family

Community

Diagram 1. Social Ecology of the Child

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

8

Diagram 2. The Social World in Individual Development

O

8

Alistair Ager, Children, war, and psychological intervention. In Psychology and the Developing World edited by

S. Carr and J. Schumaker (New York: Praeger, 1996).

The Experienced World

!"#"$%&'()

+",-%(.$

/(0",-1.(0'()

Socially

Mediated

Experience

Family

Mediated

Experience

Direct

Personal

Experience Action

Within

the World

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

9

3C 3"+22\36-16"%- 3+00+*%-41> %*. ?4@#"241>

\hile we seek what is common to human deelopment across cultures so that we might better design

projects, we also recognize that cultures dier. 1he ariation among cultures is ound in the orm,

timing, content, and meaning o social actions and behaiors. As discussed aboe, a child`s

deelopment as a social being aries according to the belies, practices, and alues embedded in a

child`s culture. Primary agents o socialization, such as the amily,` ary in deinition across cultures.

lor example, in one cultural system, amily` may mean only the immediate or nuclear amily, while

in a dierent culture, it may mean the clan or extended amily. Likewise, in some cultures the role o

peer groups can be as important as the amily or socialization. In secularized, \estern contexts,

spiritual deelopment is peripheral and ariable, but in some other cultures, spiritual deelopment

constitutes the core o indiidual and group lie.

1o design culturally appropriate interentions, one must understand and truly respect releant belies

and practices in a gien local setting. 1his is no easy task since donors and sta in leadership positions

are oten not members o the culture in which assistance is proided. O necessity, outsiders must

start rom what they know, that is, their own cultural assumptions and practices. loweer, it is

important to realize that these assumptions and practices may not apply to other cultures. A alue or

belie rom one culture-or example, the importance o building a strong sense o indiiduality-

should not be imposed on another culture as truth. Rather, it should be a basis or discussion and

seeking cross-cultural understanding. lurther, in emergencies, chaos, suering, and time pressures all

act against learning about local belies and practices. 1his tension has oten resulted in the iew that

culture and local communities are problems to be soled or obstacles to project deelopment and

implementation. Such attitudes encourage the marginalization o local people.

Ineitably, when designing psychosocial projects cross-culturally, a mixture o opportunities and

potential problems arise. I the setting is iewed as an occasion or mutual learning and using the

insights rom dierent cultures, there will likely be a rich exchange, a sense o partnership, and joint

construction o comprehensie assistance to children. On the other hand, when humanitarian

agencies disregard or minimize local belies and practices, important and inormatie opportunities or

intercultural exchange and enrichment are lost and the likelihood o imposing culturally discordant

programming is signiicantly increased. An important guiding principle is that, within each culture are

aluable insights toward proiding comprehensie assistance to its children.

1he participation o the people, including children, in the planning, implementing, monitoring, and

ealuation o the actiities that make up a psychosocial project is essential to generate ownership-o

both problems and successes-and to ensure cultural appropriateness and sustainability. Aboe all,

empowering people to take their lies into their own hands and to deelop conidence and the will to

do so is central to oercoming the deep pain and humiliation o traumatic experiences. 1his means

that time must be taken to ensure real participation. 1he participatory process o deeloping

psychosocial projects itsel can hae a proound eect on the well-being o the participants. A

participatory process will always reeal that in eery community there are local people who hae a

special interest in and an understanding o children`s needs and experiences.

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

10

?C D#24-4#*&> %*. !"+1#&14@# Q%&1+"2

Resilient children are those who hae endured and lourished despite extremely challenging and

stressul amily and social circumstances including, or example, emotionally incapacitated parents and

extreme poerty.

B*2#1 N8 L+0# 37%"%&1#"4214&2 +$ D#24-4#*1 374-."#*

9

Strong attachment to caring adults and,or peer groups

Lncouraging role models

Socially competent at interacting with adults and children

Independent and requests help when necessary

Curious and explores the enironment

Plays actiely

Adapts to change

Likely to think beore acting

Conident he or she can control some parts o his or her lie

Inoled in hobbies, actiities, and has multiple talents

As discussed preiously, children`s responses to extreme eents ary as a unction o indiidual

characteristics and enironmental actors. Children`s deelopment and resiliency will proceed as a

result o the interplay between their needs and capacities, and the risk and protectie actors within

their enironment. Resiliency can be enhanced by age-appropriate interentions that promote some o

the characteristics outlined in Inset . 1his interplay will always relect and be shaped by the culture

and local circumstances. As discussed aboe, some elements o psychosocial deelopment are speciic

to a particular culture, meaning that there is not a one size its all` approach to psychosocial

programming. A key challenge acing project designers is how cultural actors minimize or increase

risk, and promote or impede resiliency.

loweer, child deelopment theory and research does point to a set o concepts that are useul

building blocks or psychosocial projects regardless o where they are established. 1hese include

understanding what makes children resilient and the role that protectie actors play throughout

deelopment. Identiying the ways these concepts are expressed within a particular culture should

guide psychosocial project deelopment and implementation. 1hrough the study o children who

hae grown up under diicult circumstances, we hae learned that some hae certain characteristics

and social supports that hae enabled them to oercome adersity. Similarly, eatures o the social

world hae been identiied that buer the consequences o negatie experiences on children. 1hese

eatures are oten reerred to as protectie actors.

10

B*2#1 O8 !"+1#&14@# Q%&1+"2

las a close, nurturing connection to primary caregier who proides consistent and competent care

las connections to competent caring members o one`s own cultural group outside o the extended amily

Participates in amiliar cultural practices and routines

las access to community resources, including eectie educational and economic opportunities

las connections to aith and religious groups

9

Adapted from Donahue-Colletta, Understanding Cross-Cultural Child Development and Designing Programs For

Children, (PACT, 1992).

10

Ibid.

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

11

1he concept o resiliency is extremely powerul or at least two reasons. lirst, it directs our attention to

the act that all children hae assets and strengths. \e are challenged to ully appreciate the depth o

these assets and to design interentions that tap into, build on, and urther augment them. Second, the

concept o resiliency proides us with a hopeul perspectie rom which to work with children and

youth. Many times we are so ocused on the problems, deicits, and trauma that people hae endured

that it oershadows the act that children, amilies, and communities hae strengths and competencies.

Ater all, being ree` o problems` is not the same as being capable and healthy.

B*2#1 R8 D#24-4#*&> %*. !"+1#&14@# Q%&1+"28 S#22+*2 S#%"*#.

\hat has been learned about resiliency and protectie actors that might be o alue in working with children and

amilies in complex emergencies 1he ollowing are nine lessons learned.

11

Provotivg healthy deelopment and competence, vot ;v.t treativg robtev., is an important strategy or protecting

child deelopment and preenting psychosocial problems rom appearing in the irst place.

1here are potential risks, ulnerabilities, assets, and protectie actors in att people, amilies, communities, and

societies.

1he greate.t tbreat. to human deelopment are those that damage or compromise key resources and protectie

systems. 1he corollary is also true: f /e, re.ovrce. ava rotectire .,.tev. are re.errea or re.torea, cbitarev are caabte of

revar/abte re.itievce.

Resilience is typically made o ordinary processes and not extraordinary magic`-it i. a reacbabte goat.

Children who make it through adersity or recoer will bare vore human and social capital in the uture, that is

they will be in a better position to address uture problems. loweer, vo cbita i. ivrvtverabte. As risk and threat

leels rise, the relatie proportion o resilience among children will all. 1here are conditions under which no

child can thrie.

.avtt bebarior ta,. a cevtrat rote in the deelopment o all protectie systems or children.

As children grow up, they become more able to inluence their own leel o risk and degree o resiliency.

Assessments o children need to include covetevce, a..et., .trevgtb., ava rotectire factor. along with symptoms,

problems, risks, deiciencies, and ulnerabilities.

Interentions can ocus on aecrea.ivg an indiidual`s exposure to risk or adersity, ivcrea.ivg the indiidual`s

internal resources, and vobitiivg protectie processes in the social world that surrounds indiiduals.

In addition to some indiiduals exhibiting resilient qualities, communities can also be resilient. By

addressing community resilience, a more holistic approach is promoted and local resources are alued.

Inset 10 points out characteristics o resilient communities.

11

A. Masten, Resilience in Children Exposed to Severe Adversity: Models for Research and Action. Paper

presented at Children in Adversity Consultation, Oxford, 2000.

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

12

B*2#1 ;P8 L+0# 37%"%&1#"4214&2 +$ D#24-4#*1 3+006*414#2

12

1here is a strong sense o community characterized by open relationships between people and good

communication.

Leadership is shared, or leaders genuinely represent the people and both men and women are able to exercise

leadership unctions.

Supportie structures exist such as schools and pre-schools, health serices, community groups, and religious

organizations.

1here is a commitment to community deelopment. Community members take responsibility and action to

enhance community lie.

Problems such as the eects o conlict and displacement are widely acknowledged and shared rather than

indiidual problems, psychological understandings are diused broadly in the community, and there is a

commitment to deeloping collectie responses.

People see themseles as resourceul, and their communities as haing potential to meet the needs o their

people in a culturally appropriate manner, relying on external resources only when necessary.

=C 374-."#*U2 D#%&14+*2 1+ T4+-#*&#

I there is a powerul connection between the social world and indiidual deelopment, what happens

to children when their social world is disrupted By deinition, complex emergencies are high-risk

enironments, but certain eatures are especially important because o their potential impact on the

psychosocial deelopment o children.

B*2#1 ;;8 D42) Q%&1+"2 4* T4+-#*1 34"&6021%*

leatures o the social enironment that may place children in iolent circumstances at particular risk.

Lack o adequate ood, shelter, and medical care

Injury or death o a amily member

Separation rom caregiers

Injury to sel

Degree o persecution and exposure to iolence

lorced displacement rom home

Separation rom riends and community

Inadequate substitute care

Lack o economic security

Denial o educational opportunities

Lxploitation, physical or sexual abuse

1he cumulatie aect o these risk actors is to disrupt normal patterns o liing and traditional practices that proide a

powerul sense o continuity and meaning to daily lie.

13

Research and anecdotal eidence suggest that children all oer the world maniest emotional distress

ater exposure to oerwhelming, lie-threatening eents through some orm o behaioral change,

deelopmental delay or disturbance, or, at times, dramatic symptoms.` Reactions to extreme

emergencies ary because indiiduals draw on their own internal resources ,resiliencies,, as well as

resources in the enironment ,protectie actors,. Children exhibit a wide range o reactions to

iolence. Children`s reactions to traumatic eents depend on a range o risk and protectie actors, in

the child`s amily, community, and culture. A child`s reaction also depends on the depth and strength

12

D. Tolfree, Restoring Playfulness: Different approaches to assisting children who are psychologically affected by

war or displacemen (Stockholm: Radda Barnen, 1996), 87.

13

Adapted from Donahue-Colletta (1992) op cit.

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

13

o his or her own experiences and ability to cope with them. It is diicult thereore to state how any

single child will respond oer the short-term or long-term to complex emergencies. \hile on the one

hand we need to be sensitie to the unique reactions o each child, amily, and community, we also

want to help build insights into what are children`s likely reactions to iolence.

B*2#1 ;E8 374-."#*U2 D#%&14+*2 1+ T4+-#*&#

Based on experience, the ollowing are examples o reactions children may typically hae to iolence.

14

=<%0:-#2 +$ 374-."#*U2 L7+"1\9#"0 D#%&14+*2 1+ T4+-#*

lear

Clinging to parents

Mistrust and suspicion

Nightmares and night terrors

Physical complaints

Regression to deelopmentally younger orms o behaior

Sadness or depression

Restlessness, deiance, disobedience

Aggression

Disturbed relations with adults and peers

=<%0:-#2 +$ 374-."#*U2 S+*/#"\9#"0 D#%&14+*2 1+ T4+-#*&#

Preoccupation with traumatic memories

Nightmares related to the trauma and disturbances in sleep

Re-enacting trauma in play behaior

1rouble concentrating

Lack o interest in actiities

Showing o ew emotions

\ithdrawal rom others, social isolation

Constant alertness to possible danger

Guilt about suriing

Poorly deeloped moral sense o right and wrong

Loss o optimistic iewpoint toward lie

1he actual orm o expression o reactions to iolence again relates to cultural norms and belies, as

well as to the age and maturity o a child. A useul approach to these distress signals` is to

understand them as a language` whereby the child is struggling to communicate eelings and

experiences or which she or he has no adequate words, or which are connected with extreme shame

and ear and, hence, are unspeakable.` 1he challenge or those trying to support children is to

interpret` and understand this language` or behaioral expression o eelings - keeping the ocus

on establishing communication and ostering the child`s own understanding o what he or she is

experiencing. Caution needs to be taken in treating characteristic reactions as i they were all

symptoms o seere mental illness instead o normal reactions to extraordinarily negatie eents,

howeer, the potential or children to hae major mental health needs should not be ignored.

14

Donahue-Colletta (1992) op cit.

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

14

BTC 3+*&#:16%- (.@%* 4* !2>&7+2+&4%- ?#@#-+:0#*1 H 3+0:-#<

=0#"/#*&4#2

(C S4041%14+*2 +$ B*.4@4.6%-4g#. (::"+%&7#2

Much o the irst generation o psychosocial projects assisting children in crisis situations ocused on

stress, trauma, and emotional deelopment. Although potentially useul, this emphasis ultimately proed

too narrow. As recognized in the May 199 UNICLl workshop in Nairobi, psychosocial projects

should aect emotions, behaior, thoughts, memory, learning ability, perceptions, and understanding.`

Lmotional deelopment is important, but it occurs in a wider context in interaction with cognitie,

social, and spiritual deelopment. lurther, disproportionate emphasis on emotional deelopment has

oten contributed to the adoption o indiidualized approaches that ail to take into account the

powerul role o the social and cultural context o children`s deelopment. 1he use o the trauma

paradigm` to express and assess the degree o human suering caused by complex emergencies may be

limited in its ability to capture the diersity and magnitude o the eects o gross human rights

iolations.

A ocus on trauma is usually discussed in terms o post-traumatic stress reactions ,sometimes reerred

to as P1SS or P1SD-Post 1raumatic Stress Syndrome or Disorder,. 1his is deined as a delayed or

protracted response to an exceptionally stressul eent. Key symptoms include, intrusie lashbacks o

the stress eent, iid memories and dreams, and the re-experience o the original distress when the

person is exposed to similar situations.

15

Although important in some contexts, it is generally not an

eectie point o departure or psychosocial programming in situations where multiple on-going

traumatic eents are inluencing psychosocial well-being. lor example, such an approach may not take

into account concurrent distress caused by multiple losses such as loss o community, loss o

educational opportunities, uncertainty, poerty, and destruction o hope. In an emergency situation,

lie threatening or traumatic eents may change a child`s lie pathway dramatically, and this change

may hae more damaging consequences or the indiidual`s well-being than the traumatic eent itsel.

lor example, a study by Basoglu et al. ,1994,

16

looked at 1urkish actiists with a history o torture and

ound that the secondary consequences on amily, social, and economic lie were more important

predictors o outcome than the torture per se. Also, a study on Iraqi asylum-seekers in London

showed that poor social support had a closer relationship to depression than did a history o torture.

1

Additionally, a trauma orientation potentially leads to a ocus on an indiidual`s problematic reactions,

and directs attention away rom the person`s strengths, resources and the current context o his or her

lie, an essential perspectie in achieing the broader goal o enhancing psychosocial well-being. 1oo

oten such a ocus obscures sources o resilience and coping, traditional belies that color

interpretations o one`s war experiences, and local resources or healing and proiding assistance to

children. As such, taken out o context, a \estern` approach can be potentially damaging.

15

As defined by WHO in: John Orley, Health Activities Across Traumatized Populations: WHOs Role Regarding

Traumatic Stress. In International Responses to Traumatic Stress, edited by Yael Danieli, Nigel S. Rodley, and Lars

Weisaeth (Amityville, NY: Baywood Publishing Company,1996), 388.

16

M. Basoglu,, M. Parker, E. Ozmen, O. Tasdemir, and D. Sahin, Factors related to long-term traumatic stress in

survivors of torture in Turkey, Journal of the American Medical Association 272 (1994): 357-63.

17

C. Gorst-Unsworth and E. Goldenberg, Psychological sequelae of torture and organized violence suffered by

refugees from Iraq; Trauma-related factors compared to social factors in exile, British Journal of Psychiatry 172

(1998): 90-4.

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

15

\hile recognizing that there is a dearth o research on the relationship between experienced trauma

and mental illness, especially or children, caution should be used when using a \estern trauma

paradigm` that potentially leads to an indiidualized approach. Such an approach can be stigmatizing.

1here may be a role or more intensie` interentions or those most aected, howeer, they should

be culturally appropriate and based on indiidual`s strengths and resources. Perhaps the most eident

drawback o an indiidual approach is that the model may not explore the most pernicious and long-

lasting eects o bitter ciil wars-the destruction o relationships between and among people o the

kind necessary to sustain surial, meaning, alues, and hope.

_C Z+@4*/ $"+0 B*.4@4.6%-2 1+ 3+006*414#2

Complex emergencies disrupt both indiidual and community unctioning in that the weakening o

either will likely hae a negatie impact on the other. At the community leel, psychosocial eects o

complex emergencies are oten seen when neighbors no longer trust each other, no longer relate to

one another, and in some instances are hostile to each other. 1he breakdown o cohesion can be

ound in the disruption o normal patterns o liing and traditional practices that proide a sense o

continuity and meaning. 1he rupture o trust and riendship has serious generational consequences

or the unctioning o community lie and the iability o societies as a whole. It is with these

combined eects that children and their amilies struggle to cope.

It is thus ital to connect work on psychosocial healing with eorts to build tolerance and

reconciliation. Psychosocial projects with a \estern model o mental health oten strongly encourage

emotional expression as a means o aiding emotional healing. But in an ethnically diided context,

such emotional expression and enting typically occurs among members o one's own group. In such

circumstances there is risk that expressions o suering can be a way to inappropriately alorize

suering. \hen traumatic memories become badges o honor, they can sere as warrants or reenge

that can contribute to ongoing cycles o iolence and belies that iolence is justiied. In Kosoa, or

example, the strengthening o one`s cultural identity can become a justiication or mistreating the

other groups. Groups that eel assaulted on cultural grounds, whether Albanian or Serbian, hae a

powerul need to adance, express, and reclaim their own culture. 1o preent additional iolence,

howeer, this reclamation must be integrated with wider eorts o building tolerance and peace.

1hese experiences underscore the act that healing must be social as well as indiidual, and it needs to

occur across the lines o conlict. In a war zone, healing cannot be approached eectiely as a singular

endeaor, it must be holistic and include actiities that build tolerance and reconciliation.

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

16

37%:1#" V*# L600%">

1here is a need to broaden the deinition o psychosocial to recognize the holistic, integrated

nature o child deelopment and to situate it within an ecological perspectie.

At its core, psychosocial programming is about emotional healing, social reconciliation, and

community building. 1o do this, eorts must moe beyond indiidual well-being and seek to

oster community rebuilding and reconciliation.

A positie deelopmental enironment is one that consistently proides children with

opportunities and challenges to deelop as competent social beings. Many actors such as

adequate nutrition, good health, and reedom rom disability will play a role in the rate and quality

o a child`s psychosocial deelopment and well-being.

\hen designing psychosocial projects, the participation o communities is important so that

protectie actors and resiliencies may be recognized and harnessed in culturally appropriate and

sustainable ways. 1he capacity to respond in an integrated way to the ull range o children`s and

community`s needs is a continuing challenge to practitioners, especially under emergency

conditions.

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

17

Chapter Two

37%:1#" E8 M7%1 B2 !2>&7+2+&4%- !"+/"%004*/W

1bi. cbater offer. a aefivitiov of .,cbo.ociat rogravvivg ava roriae. a ai.cv..iov of tbe aivev.iov. of .,cbo.ociat

rogravvivg, ivctvaivg fvvaavevtat goat., target ovtatiov, ro;ect covtevt, ava ro;ect aroacb. 1be cbater

covctvae. ritb a brief ovttive of va;or ro;ect area. ava tbeir ivortavce for rovotivg tbe .,cbo.ociat rettbeivg of

cbitarev, favitie., ava covvvvitie..

BC ?#$4*414+*

Child-ocused psychosocial projects are those that promote the psychological and social well-being

and deelopment o children. 1he orientation here is that child deelopment is promoted most

eectiely in the context o the amily, community, and culture. At its most undamental leel,

psychosocial programming consists o actiities designed to adance children's psychological and

social deelopment, to strengthen protectie and preentie actors that can limit the negatie

consequences o complex emergencies, and to promote peace-building processes and reduce tensions

between groups. Inset 13 identiies undamental goals o psychosocial programming.

B*2#1 ;G8 Q6*.%0#*1%- X+%-2 +$ !2>&7+2+&4%- !"+/"%004*/

Secure attachments with caregiers

Meaningul peer relationships, riendships, and social ties, social competence

A sense o belonging

A sense o sel-worth and alue, sel-esteem and well-being

1rust in others

Access to opportunities or cognitie and spiritual deelopment

Physical and economic security

lope, optimism, and belie in the uture

Many dierent types o projects may be implemented to support these undamental goals. 1he

diersity is illustrated by the ollowing sample interentions:

1racing and reuniication o unaccompanied children with their amilies

lood aid and distribution projects

Projects to address the psychosocial eects o armed conlict

Projects or the social reintegration o ormer child soldiers

Violence preention and peace education projects

Larly stimulation projects or inants

Larly child deelopment projects

lealth projects or children and parents

Positie parenting projects

Vocational training projects or adolescents and adult caregiers

Lducational and cultural projects

Awareness training on children`s needs and rights

Adocacy or greater protection and implementation o children`s rights

Good Practices in Evaluating Psychosocial Programming

18

1he promotion o psychosocial well-being may be accomplished through a ariety o approaches. It

may be the main ocus o a discrete or stand-alone project, or it can be integrated with other projects,

such as ood security, health, or shelter. As stated in Chapter One, the alue o integrating

psychosocial dimensions into other emergency interentions should not be underestimated. lor

example, a child health project will hae limited success i caregiers are oerwhelmed and unable to

make eectie decisions about amily health management. A holistic approach, which addresses

immediate health concerns while acknowledging the importance o the amily system, is more likely to

result in desired project impact because it addresses caregiers` needs as well.

BBC ?40#*24+*2 +$ !2>&7+2+&4%- !"+/"%004*/

1o better understand the host o project strategies that can be designed, it is useul to organize them

along three dimensions, according to the ovtatiov beivg targetea, tbe covtevt of tbe ro;ect itsel, and the

ro;ect aroacb being implemented. 1hese three dimensions are described below.

(C 9%"/#1 !+:6-%14+*

Children and amilies who are part o the same community and hae endured the same sequence o

eents will neertheless hae dierent experiences and responses. \e distinguish between three

groups, according to the degree o risk:

1. ereret, .ffectea Crov

1he psychological and social unctioning o some children and adults may be seerely compromised.

\hile generally a small percentage o the oerall population

18

,represented in the diagram below as

10,, this group requires intensie psychological attention because they are unable to manage on their

own. Children orced to iew and,or commit iolent acts, such as child soldiers, are likely to all into

this group. More time-intensie, indiidualized approaches are likely to be the most appropriate

responses, where social and cultural resources permit. Len i bolstered by project support, most

community-based attempts are inadequate to rebuild psychological unctioning unless coupled with an

eectie identiication and reerral system or more indiidualized support. 1his group is in need o

one-on-one attention in order to address the more seere traumatic and,or depression disorders, or

example. lor the small percentage o children who require special assistance, one-on-one attention

can be proided in the orm o traditional rituals or other local cultural practices, and should not be

limited to \estern-deried responses such as psychological counseling. 1here is little research

aailable on how to best address these more seere needs in emergencies, and, because o the high

cost per beneiciary required to address the needs o this proportionally smaller group, most

international relie organizations must by necessity ocus on reaching larger numbers o children

aected-the at-risk and more generally aected groups-through community-based interentions.

2. .tRi./ Crov

A second segment o the community ,represented at 20 in the diagram below, consists o those

who hae experienced seere losses and disruption, are signiicantly distressed, and may be

experiencing despair and hopelessness, but whose social and psychological capacity to unction has

not yet been oerwhelmed. Children and adults in this category may be suering rom acute stress

disorder ,the most extreme, or exaggerated normal reaction to iolence and trauma,. 1hey may hae

lost amily members in the iolence, they may hae witnessed deaths, or they may be ictims o

iolence. 1his group is at particular risk or psychological and social deterioration i their

18