Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Case Study of Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Policies in Rio de Janeiro-Libre

Uploaded by

CharlesLaffiteauOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Case Study of Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Policies in Rio de Janeiro-Libre

Uploaded by

CharlesLaffiteauCopyright:

Available Formats

1

What types of climate change mitigation and adaptation policies are being considered or

implemented in Rio de Janeiro?

Author: Charles Laffiteau

Introduction

As the host city for both the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics, theory

suggests that, based on the experience of Beijing and China when it hosted the 2008 Summer

Olympics, the Brazilian national government, as well as the state and municipal governments of

Rio de Janeiro, will be expending considerable capital on the sports infrastructure required to

host these major sporting events. But just as the governments of China and Beijing also made

large expenditures on improving urban transportation and reducing harmful air pollutants, so too

will the governments of Brazil and Rio de Janeiro also have to make similar investments in order

to mitigate the potential adverse impacts of urban pollution on the health and well being of both

athletes and spectators. Furthermore Rio de Janeiro will also have to beef up its disaster

preparedness planning in order to avoid the potential negative fallout on tourism that would

result from a catastrophic weather event before or during these major international sporting

events. A flooding event similar to those which have recently affected Bangkok and Mumbai

would be disastrous not only for the citys slum dwellers, but also for the general publics and

the rest of the worlds international image of Rio de Janeiro and Brazil. This leads to me to my

development case study research question which is What types of climate change mitigation

and adaptation policies and strategies are being considered or implemented in Rio de Janeiro?

The importance of this question is due to the fact that up until recently, the emphasis of

public policy in Brazil and most of the developing world has largely been on economic growth

and sustainability. But as necessary as these economic development efforts are, it is clear that

more attention needs to be given to adaptation to the climatic changes that are already underway

2

and mitigation strategies to reduce the adverse impacts of future emissions of greenhouse gases.

Reducing GHG emissions from factories, electric utilities, cars and trucks is an important

element of climate change mitigation plans, while disaster preparedness and management plans

are vital components of an adaptation strategy. But to design these, policy makers need a better

understanding of which people and systems are vulnerable to climate hazards and what makes

them vulnerable, especially the poor slum dwellers living in cities like Rio de Janeiro.

Research Methods

To answer the research question I used the key words climate change, global warming,

policies, strategies, Third World, developing countries, cities, urban, financing, prevention,

weather disasters, mitigation, adaptation, prevention, planning, risk management, sea level rise

and combinations of these key words in searches for books, academic papers and journal articles

in the WorldCat database, articles in journals such as Environment and Urbanization and Cities.

I then used these same key words and combinations of them in my searches of other sources such

as NGOs and intergovernmental organizations like the World Bank, IPPC and UNFCC that deal

with the impact of climate change on cities and urban environments in developing countries.

Finally, I also included journal articles and books that deal with climate change related disaster

preparedness in my searches for information given the fact that coastal cities like Rio de Janeiro

are especially vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

Given the relative paucity of academic articles and studies dealing with climate change

adaptation and mitigation in Rio de Janeiro, another import source of information was using my

key words and combinations of them to search the internet for newspaper articles and blogs for

interviews with Rio de Janeiro political leaders and policymakers about Rios climate change

mitigation and adaptation policies as well as weather related disaster planning strategies.

3

Rio de Janeiro Policy Makers Perspective

In his speech to the 2012 TED Conference, Rio de Janeiro Mayor Eduardo Paes said he

believed that policy makers in cities of the future like Rio de Janeiro needed to be guided by four

basic principles and then provided examples of how they are practiced in Rio de Janeiro. Paes

said that first; a city of the future has to be environmentally friendly. He explained that Every

time you think of a city, you have to think green, green, green. Every time you see concrete

jungle you must find open spaces. And when you find open spaces, make it so people can get to

them. He then went on to say that that making the city more environmentally friendly was the

principle underlying the creation of the third largest urban park in Rio, due to open by June 2012.

Paes second principle was that a city of the future has to deal with mobility and

integration of its people. He said that because cities are packed with people, high-capacity

transportation is critically important. However Paes also notes that these systems are very

expensive and then goes on to reference a project to redesign the urban plan of Curitiba Brazil so

that 63% of Rio de Janeiros population will be carried by its new BRT system by 2015.

Paes says that the third principle is that a city of the future has to be socially integrated.

Paes acknowledges the favelas that are prominent in Rio but he does not agree that they are

necessarily a problem. Paes maintains that if you deal with them properly, favelas can even be

their own solution. Over 1.4 million of Rios 6.3 million inhabitants live in favelas but Paes

claims that you can change the favelas vicious circle of poverty to a virtuous one if you bring

education, health and open spaces to the favelas. His aim is to urbanize the favelas by 2020.

Paes fourth principle is that a city of the future has to use technology to be present. As

an example of what he means, Paes notes that since February is high season in Rio de Janeiro

he shouldnt be away from the city attending the TED Conference. But, Paes says that thanks to

4

technology can leave the country because technology in the citys Operation Center allows him

to check up on the state of the city, on the weather, the traffic and even on the location of the

citys waste collection trucks while he is out of the country. Paes concludes that At the end of

the day, the city of the future is a city that cares about its citizens and integrates its citizens.

1

Climate Change Mitigation in Rio de Janeiro

The IPCCs 2007 (Fourth) Assessment concluded that creating synergies between

adaptation and mitigation can increase the cost-effectiveness of actions and make them more

attractive to stakeholders, including potential funding agencies.

2

But as Bartlett et al note; most

of this synergy between mitigation and adaptation policies is in wealthier nations; in most urban

areas in low-income nations, there is not much to mitigate because greenhouse gas emissions are

so low.

3

Therefore it isnt too surprising that there doesnt yet appear to be much synergy

between Rio de Janeiros climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies. However, in

contrast to large cities in many other developing countries that are primarily focused on adapting

to climate change and planning for extreme weather events, Rio de Janeiro has also begun to

implement some strategies and policies that are designed to mitigate climate change by reducing

the citys overall GHG emissions.

Because Brazil generates more than 75% of its electricity from hydroelectric power, there

are few opportunities for cities like Rio de Janeiro to reduce their GHG emissions other than

through activities related to their transport systems and waste management. Dubeux and La

Rovere have conducted studies which show that 60% of Rio de Janeiros GHG emissions are

1

Eduardo Paes. Mayors Voices: Mayor of Rio de Janeiro Eduardo Paes: Interview at Ted 2012 Conference C40 Cities Live

Blog (March 2, 2012)

2

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Climate Change: Impacts, Vulnerabilities and Adaptation in

Developing Countries. (Bonn Germany: Information Services of the UNFCCC Secretariat, 2007)

3

Sheridan Bartlett, David Dodman, Jorgelina Hardoy, David Satterthwaite and Cecilia Tacoli, Social Aspects of Climate

Change in Urban Areas in Low and Middle Income Nations International Institute for Environment and Development and

Instituto Internacional de Medio Ambiente y Desarrollo. Paper presented at Fifth Urban Research Symposium 2009: Cities and

Climate Change: Responding to an Urgent Agenda. (June 28-30, 2009) Marseille, France:22

5

generated by energy consumption for transportation and that the second largest source of GHG

emissions is the waste management sector which accounts for another 37%. Probably the most

visible climate change mitigation policy initiative in Brazil is the use of flex fuel vehicles that

run on either a 75/25% mixture of gasoline and ethanol or 100% pure ethanol made from

sugarcane. Flex fuel vehicles have been a commercial success and Brazils 16.3 million flex fuel

vehicles comprise the largest fleet of flex fuel vehicles in the world. Studies conducted by

UNICA, Brazils ethanol industry trade association show that thanks to these vehicles us of

cleaner burning ethanol and ethanol gasoline blends Brazil emitted 83.5 million fewer tons of

carbon than it would have emitted had those vehicles been using gasoline instead of ethanol.

As regards reducing GHG emissions through waste management, Dubeux and La Rovere

note that Brazil currently has two successful experiences in Clean Development Management

(CDM) projects based on local initiatives that involve landfill gas burning, one of which is in

Nova Iguacu, in Rio de Janeiro state.

4

The authors conclude that just as the widespread use of

ethanol provides other benefits beyond the climate change impacts of reduced GHG emissions

such as enhanced energy security, landfill gas burning in conjunction with the CDM also

provides other benefits as well. The authors claim that; additional income from GHG emissions

reduction projects can help control local pollution and achieve other types of benefits such as

lower public expenditure, traffic improvement and reductions in atmospheric pollution, among

other aspects that are important to the quality and everyday life of communities.

5

But Rio de Janeiro has also taken other steps beyond gas burning to reduce its GHG

emissions. Rio de Janeiro is also the home of the worlds largest garbage dump, Jardim-

Gramacho, and this garbage dump is the source of many waste products used in recycling. As a

4

Carolina Burle Schmidt Dubeux and Emilio Le`bre La Rovere. Local perspectives in the control of greenhouse gas emissions

The case of Rio de Janeiro. Cities (Vol. 24, No. 5, 2007): 354

5

Dubeux and La Rovere: 363

6

nation, Brazil has also long been a leader in the recycling of aluminum, steel, glass and plastics.

Brazil leads world by recycling 96.5% of its aluminum cans and ranks second to Japan in

recycling plastic bottles. Brazil also ranks third in recycling steel cans, fourth in recycling plastic

solids and fifth in recycling glass bottles. Recycling is a very practical climate change mitigation

strategy that helps reduce GHG emissions because less fossil fuel energy is used to produce new

glass, aluminum and steel containers and less oil is used to produce new plastic bottles and

solids. However, in contrast to the recycling programs used by more developed countries like

Japan and the United States (US), instead of household collection, most is of Brazils recycling is

accomplished by poor favela residents picking through rubbish piles and garbage dumps like the

one at Jardim-Gramacho.

With the assistance of funding from the World Bank, Rio de Janeiro and its main electric

utility, Light Servios de Electricidade, have attempted to incorporate recycling into its attempts

to provide safe electrical service to the favelas under the Program for Normalization of Informal

Areas. According to the World Bank, in Rios favelas, the struggle to find work and have access

to basic social services is exacerbated by the threat of fire, electrocution and power outages.

These additional risks stem from the often desperate steps residents take to bring electricity to

their meager homes, which are often connected illegally and with extreme risk to the power

network. Part of the solution is to find ways to deal with infrastructural inadequacies, to provide

essential services at a low cost, and to educate favela residents about proper power use.

Under the Program for Normalization of Informal Areas, Light is working in the city's

low-income communities to establish and upgrade power networks, install transformers and

meters, and educate local residents about safe, cost-effective power usage. Light is working

hand-in-hand with local NGOs on a program to establish and upgrade power networks, install

7

transformers & meters, to provide favela residents safe, cost-effective power. It also documents

proof of residence for favelos, necessary for getting a phone and establishing credit. But Light

goes a step further by encouraging recycling within the companys concession area with a

program that gives favela residents money off their electricity bills in exchange for paper, plastic,

aluminum, steel and glass bottles that can be used to cut GHG emissions through recycling.

6

Rio de Janeiro and other cities in developing countries suffer from the effects of urban

sprawl thanks to an explosion of new residents spawned by increased rural to urban migration.

Torres and Pinho write that Sprawl is commonly viewed as an unsustainable option although

there is no consensus among academics and planners about the notion of a right density.

Diffuse developments increase distances between trip origins and destinations and, as a

consequence, traveled distances. Such developments not only increase air pollution and energy

consumption but also increase infrastructural and public service costs. They have negative

impacts on historical city centres and as well as other physical and social costs.

7

One project designed to both address Rio de Janeiros urban sprawl transport problems

and mitigate climate change by reducing Rio de Janeiros GHG emissions is the World Banks

Additional Financing for the Upgrading and Greening of the Rio de Janeiro Urban Rail System

Project. This project is envisioned to improve the level of service provided to suburban rail

transport users in the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region (RJMR) in a safe and cost-efficient

manner; and to improve the transport management and policy framework in the RJMR.

According to the World Bank, this additional financing loan will be used to scale up a well-

performing project in order to strengthen its policy component and further enhance the level of

service provided by the urban rail system to make it more attractive to bus and automobile users

6

World Bank. Bringing Light to Slums of Brazil. Program for Normalization of Informal Areas (September 17 2002)

7

Miguel Torres and Paulo Pinho. Encouraging low carbon policies through a Local Emissions Trading Scheme (LETS). Cities

(Vol. 28 No. 3, 2011): 577

8

and to promote climate change mitigation and adaptation in the long term. The US$600 million

loan from the World Bank will create a better quality of life in Rio and a reduction of 93,700

tons of greenhouse gas emissions, equivalent to over 25,000 gasoline passenger cars. But it will

also finance the development of a sustainable transport strategy for the state of Rio de Janeiro,

including reducing the overall carbon footprint of the system, and the establishment of a climate

change natural disaster monitoring centre.

8

Rio de Janeiros Mayor, Eduardo Paes, also cites Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) as another

example of addressing the problem of urban sprawl and mitigating climate change by dealing

with the mobility and integration of Rio de Janeiro residents in an environmentally friendly way.

Paes says that BRTs four exclusive lanes for articulated buses that can carry up to 160

passengers are currently being built by the Rio de Janeiro City Hall and users will be able to

board its buses on acclimatized stations, where they will buy their tickets and connect with the

train and underground systems. Paes claims that after construction is completed, BRT will allow

Rio de Janeiro to increase the percentage of citizens who use high capacity public transport from

the current 18% to 63% in 2015.

9

Climate Change Adaptation in Rio de Janeiro

Hardoy and Pandiella acknowledge that several factors explain why extreme weather

events related to climate change fail to motivate the general public to demand that political

leaders take the actions that are needed to adapt to climate change and or mitigate some of its

most damaging effects. The negative consequences associated with floods, droughts and extreme

temperatures attract a lot of media attention and commentary by local authorities in the days and

weeks following their occurrence. However, much like other natural disasters that are not

8

World Bank. Upgrading and Greening the Rio de Janeiro Urban Rail System Additional Financing. (February 22 2012)

9

Paes interview: (March 2, 2012)

9

weather related like earthquakes and tsunamis, many of the people displaced by these disasters

are quickly forgotten when the media turns its attention elsewhere later. But these authors claim

that for the urban poor living in cities like Rio de Janeiro the lack of appropriate actions has to do

with the long-evident incapacity of governments to address risk and to integrate development

with the reduction of vulnerability.

10

In some cases governments lack the necessary data they need to develop credible disaster

plans while in other cases local officials lack the resources and or capacities needed to develop

and support disaster preparedness plans. But even if those case where they do have the necessary

resources the authors say that In practice, governments still tend to concentrate on emergency

response and recovery and have been slow to adopt an integrated disaster prevention and

preparedness approach, which needs an understanding of vulnerability and risk accumulation

processes and a capacity and willingness to work with those who are vulnerable.

11

But are cities like Rio de Janeiro also part of the problem or are they more likely part of

the solution to climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies? David Dodman points out

that detailed analyses of urban greenhouse gas emissions for individual cities suggest that per

capita urban residents tend to generate a substantially smaller volume of greenhouse gas

emissions than residents elsewhere in the same country.

12

On the basis of this information it

would appear that the acceleration in rural to urban migration that Rio de Janeiro and large cities

in other developing countries have been experiencing over the past fifty years could help

mitigate climate change by reducing per capita GHG emissions. Instead of complaining about the

pressure this places on urban infrastructure maybe we should focus on adapting to it.

10

Jorgelina Hardoy and Gustavo Pandiella. Urban poverty and vulnerability to climate change in Latin America. Environment

and Urbanization (Vol. 21 No. 1, 2009): 203

11

Hardoy and Pandiella: 220

12

David Dodman. Blaming cities for climate change? An analysis of urban greenhouse gas emissions inventories Environment

and Urbanization (Vol. 21 No. 1, 2009): 186

10

On the other hand, the accelerated migration of Brazils rural poor into large urban

metropolises like Rio de Janeiro cannot help but have a negative impact on a local environment

that isnt designed to accommodate such large densities of human inhabitants. Hamza and Zetter

note that Urban growth on such a large scale cannot avoid having a major environmental

impact. Environmental degradation increases disaster vulnerability, and every disaster has an

additional negative environmental impact.

13

While urban officials could try to slow the influx of

poor rural residents into cities like Rio de Janeiro and reduce pressure on the local environment,

it simply isnt realistic to expect that they can do anything to change these migration patterns.

Hamza and Zetter also note this writing that, Spontaneous growth has been the norm in many

developing countries, and spatial policies have a very poor record in achieving their purposes.

14

Charles Mueller observes that in the case of Rio de Janeiro The areas settled by the

urban poor are often environmentally fragile, and a concentration of population there contributes

to their degradation. Moreover, they are usually dangerous and, occasionally, the threats they

pose materialize through surges of flooding and landslides.

15

While many middle class and

wealthy residents of Rio de Janeiro also locate their homes on the same hillsides and low lying

areas that are susceptible to flooding, unlike the favela residents they can afford to reinforce their

homes and insure them as well as lobby local officials to enact policies to protect their

neighborhoods. On the other hand the most vulnerable groups, the poor, the elderly, women and

children have little or no voice in the disaster preparedness plans for the areas they live in.

Rio de Janeiros unique geography also makes it more prone to weather related disasters.

The Atlantic rainforest that once covered the hills surrounding the city has been stripped away

13

Mohamed Hamza and Roger Zetter. Structural adjustment, urban systems, and disaster vulnerability in developing countries.

Cities (Vol. 15 No. 4, 1998): 296

14

Hamza and Zetter: 293

15

Charles C. Mueller. Environmental problems inherent to a development style: degradation and poverty in Brazil.

Environment and Urbanization (Vol. 7: No. , 1995)2: 67-84

11

and its low lying over the years to create space for housing and this has caused increased erosion

of the thin soils that cover the underlying granite leading to land and mudslides. Many of the low

lying coastal marshes and lagoons have also been filled in thus reducing Rios capacity to absorb

excessive amounts of rainfall. Sherbinin et al also note that Rio has never been impacted by

tropical cyclones, although this may change. The first recorded South Atlantic hurricane reached

land in the state of Santa Catarina in March 2004, suggesting that what was once thought to be a

meteorological impossibility is no longer so, with global warming-induced increases in regional

sea surface temperatures.

16

Since there is little policy makers can do to slow the growth of cities

like Rio de Janeiro they should instead focus on managing that growth in a sustainable manner

while also addressing the needs of the most vulnerable segments of society. Rios urban sprawl

and unique geographic considerations also underscore the need for policy makers to devise

policies that account for the impact of new housing and business enterprises on the local ecology.

With respect to climate change adaptation, Obermaier et al note that Adaptation has now

become a priority on the Brazilian government agenda, as evidenced by the National Climate

Change Policy Plan (Governo Federal, 2008) recently put forward by the President to the

Congress.

17

However, the fact that climate change adaptation has become a priority for Brazils

political leaders isnt too surprising since one of the predictions of climate change is that

problems such as sea level rise and flooding are expected to become even worse in the coming

decades due to the effects of climate change and an increase in extreme weather events. Indeed

Rio de Janeiro recently experienced extreme rainfall events and extensive flooding in April 2010

that caused 292 fatalities and more disastrous rains again less than a year later in January 2011

16

Alex De Sherbinin, Andrew Schiller and Alex Pulsipher. The vulnerability of global cities to climate hazards. Environment

and Urbanization (Vol.19 No. 1, 2007):53

17

Martin Obermaier, Maria Regina Maroun, Debora Cynamon Kligerman, Emilio Lbre La Rovere, Daniele Cesano, Thais

Corral, Ulrike Wachsmann, Michaela Schaller and Benno Hain. Adaptation To Climate Change In Brazil: The Pintadas Pilot

Project And Multiplication Of Best Practice Examples Through Dissemination And Communication Networks. paper presented

at RIO 9 - World Climate & Energy Event, (17-19 March 2009), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil:189

12

that led to 903 fatalities. But with a large international news media contingent and a global TV

audience, another flooding event similar to these during the 2014 World Cup or 2016 Summer

Olympics would be disastrous not only for Rios slum dwellers, but also for tourism and the

general publics as well as the worlds international image of both Rio de Janeiro and Brazil.

In their recent assessment of Rios climate change adaptation policies and disaster

planning strategies, Young and Nobre write that Extreme events such as intense rainfalls have

shown to be a growing problem in many areas in the world, including the city of Rio de Janeiro.

But Rios risk situations are also a consequence of a social process related to structural urban

issues that are linked to political decisions.

18

Sherbinin, Schiller and Pulsipher then cite an

example of precisely how structural urban issues linked to political decisions have exacerbated

the negative consequences associated with extreme weather. Building pedestrian sidewalks in

Rios favelas is a public policy measure that has long been used by Rios political leaders to

garner political support by helping favela residents safely navigate their neighborhoods narrow

urban thoroughfares and integrating these communities into Rios transportation network.

Unfortunately paved concrete sidewalks also contribute to GHG emissions both during

the concrete production process and after they have been built by reflecting rather than absorbing

solar radiation. Furthermore, Sherbinin et al write that: Although favelas have always suffered

during rainy seasons, the paving of walkways has had the effect of increasing runoff to the point

where water is often ankle or knee deep between houses. Runoff from communities on steep

hillsides is channeled down cemented watercourses to the coastal lowlands where they join

canals whose limited flow capacity causes frequent flooding.

19

18

A. Young and C. Nobre. Climate Change Vulnerability in Rio de Janeiro: an integrated case study of sea level rise and

flooding. Paper presented at Planet Under Pressure 2012 (March 26-29, 2012) London, UK

19

Sherbinin et al : 51

13

Rio de Janeiros city planners are now aware of these unintended negative consequences

of building new sidewalks in the favelas, but favela residents continue to favor the construction

of even more sidewalks. As a result, politicians continue to push for more sidewalks while city

planners struggle to devise alternative pedestrian strategies. But Rios city planners are in a

difficult position because as Jordi Oliver-Sol et al point out; there is a lack of environmental

tools to guide urban planners through design/redesign processes and quantitative research on the

global environmental impacts of urban infrastructures is still in its early stages.

20

A key element in Rio de Janeiros plans for adapting to climate change and the extreme

weather events associated with it is the use of technology. As an example of how Rio de Janeiro

is using technology to help adapt to future climate change related weather events, Paes cites the

capabilities of Rios Operations Center. Paes describes the Operations Centre as a nerve centre

where we monitor all logistics of the city, from waste management and traffic control to weather

and climate-related incidents. Using IBM technology, a 250-km-radius radar and 560 cameras,

the Operations Centre allows us to be present when and where we are needed.

21

In addition to better development planning to account for local ecological considerations,

adapting to climate change will also require an increase in the resources Rio de Janeiro will need

to respond to future climate change related weather events. As Christoplos, Mitchell & Liljelund

observe; A central objective of disaster preparedness is to increase the efficiency, effectiveness

and impact of disaster response. But despite massive investment in relief skills training by many

agencies, the impact has been mixed, and it is clear that the same mistakes have been made again

and again due to the difficulties in sustaining capacity between disasters.

22

20

Jordi Oliver-Sol, Alejandro Josa, Alejandro Arena, Xavier Gabarrell and Joan Rieradevall The GWP-Chart: An

environmental tool for guiding urban planning processes. Application to concrete sidewalks. Cities (Vol. 28 No. 1, 2011): 247

21

Paes interview: (March 2, 2012)

22

Ian Christoplos, John Mitchell and Anna Liljelund. Re-framing Risk: The Changing Context of Disaster Mitigation and

Preparedness. Disasters (Vol. 25 No. 3, 2001):195

14

Conclusions

Although I only found a few articles that address measures that have been taken to deal

with the negative impacts of climate change and related weather events on Rio de Janeiros

residents and its governments disaster planning strategies, it would appear that Rio de Janeiros

public officials are at least beginning to take some of the steps that are necessary to both mitigate

climate change and adapt to its negative impacts. However this observation is based primarily on

a February 29, 2012 interview conducted with Rio de Janeiro Mayor Eduard Paes at the 2012

TED Conference in Long Beach CA and the programs he mentioned in this interview, rather than

the scholarly assessments of Rio de Janeiros climate change mitigation and adaption strategies

that were mentioned in the articles and scholarly literature that was reviewed for this paper.

As previously noted in the policymakers perspective section, in his speech to the 2012

TED Conference, Rio de Janeiro Mayor Eduardo Paes said that four most important attributes of

future cities would be; 1) to be environmentally friendly, 2) to deal with mobility and integration

of its people, 3) to be socially integrated, and 4) to use technology effectively. Based on this

review of Rio de Janeiros climate change mitigation and adaptation policies it would also appear

that Rios policymakers are indeed using these principles to guide them in the development of

Rios climate change policies. But political will is also an essential element in devising climate

change mitigation and adaptation strategies and policies that dont unnecessarily intrude on

economic development progress in cities like Rio de Janeiro. Christoplos, Mitchell & Liljelund

note the necessity of political will is due to the fact that for political leaders; The political costs

of redirecting priorities from visible development projects to addressing abstract long-term

threats are great. It is hard to gain votes by pointing out that a disaster did not happen.

23

23

Christoplos et al:195

15

Bibliography

Bartlett, Sheridan, David Dodman, Jorgelina Hardoy, David Satterthwaite and Cecilia Tacoli,

Social Aspects of Climate Change in Urban Areas in Low and Middle Income Nations

International Institute for Environment and Development and Instituto Internacional de

Medio Ambiente y Desarrollo. Paper presented at Fifth Urban Research Symposium

2009: Cities and Climate Change: Responding to an Urgent Agenda. (June 28-30, 2009)

Marseille, France: 1-44

Christoplos, Ian, John Mitchell and Anna Liljelund. Re-framing Risk: The Changing Context of

Disaster Mitigation and Preparedness. Disasters (Vol. 25 No. 3, 2001):185-198

Dubeux, Carolina Burle Schmidt and Emilio Le`bre La Rovere. Local perspectives in the

control of greenhouse gas emissions The case of Rio de Janeiro. Cities (Vol. 24, No. 5,

2007): 353364

Dodman, David. Blaming cities for climate change? An analysis of urban greenhouse gas

emissions inventories Environment and Urbanization (Vol. 21 No. 1, 2009): 185-201

Hamza, Mohamed and Roger Zetter. Structural adjustment, urban systems, and disaster

vulnerability in developing countries. Cities (Vol. 15 No. 4, 1998): 291-299

Hardoy, Jorgelina and Gustavo Pandiella. Urban poverty and vulnerability to climate change in

Latin America. Environment and Urbanization (Vol. 21 No. 1, 2009): 203-224

Mueller, Charles C. Environmental problems inherent to a development style: degradation and

poverty in Brazil. Environment and Urbanization (Vol. 7: No. , 1995)2: 67-84

Obermaier, Martin, Maria Regina Maroun, Debora Cynamon Kligerman, Emilio Lbre La

Rovere, Daniele Cesano, Thais Corral, Ulrike Wachsmann, Michaela Schaller and

Benno Hain. Adaptation To Climate Change In Brazil: The Pintadas Pilot Project And

16

Multiplication Of Best Practice Examples Through Dissemination And Communication

Networks. paper presented at RIO 9 - World Climate & Energy Event, (17-19 March

2009), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil:185-190

Oliver-Sol, Jordi, Alejandro Josa, Alejandro Arena, Xavier Gabarrell and Joan Rieradevall The

GWP-Chart: An environmental tool for guiding urban planning processes. Application to

concrete sidewalks. Cities (Vol. 28 No. 1, 2011): 245-250

Paes, Eduardo. Mayors Voices: Mayor of Rio de Janeiro Eduardo Paes: Interview at Ted 2012

Conference C40 Cities Live Blog (March 2, 2012) available online at:

http://live.c40cities.org/?d=c40.com¤tPage=8

Sherbinin, Alex De, Andrew Schiller and Alex Pulsipher. The vulnerability of global cities to

climate hazards. Environment and Urbanization (Vol.19 No. 1, 2007): 39-64

Torres, Miguel and Paulo Pinho. Encouraging low carbon policies through a Local Emissions

Trading Scheme (LETS). Cities (Vol. 28 No. 3, 2011): 576-682

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Climate Change: Impacts,

Vulnerabilities and Adaptation in Developing Countries. (Bonn Germany: Information

Services of the UNFCCC Secretariat, 2007)

World Bank. Bringing Light to Slums of Brazil. Program for Normalization of Informal Areas

(September 17 2002)

World Bank. Upgrading and Greening the Rio de Janeiro Urban Rail System Additional

Financing. (February 22 2012)

Young, A. and C. Nobre. Climate Change Vulnerability in Rio de Janeiro: an integrated case

study of sea level rise and flooding. Paper presented at Planet Under Pressure 2012

(March 26-29, 2012) London, UK

You might also like

- Capitol BuildingDocument1 pageCapitol BuildingCharlesLaffiteauNo ratings yet

- The Appellate Body of The WTO in The United States Ban On Shrimp and Shrimp Products-LibreDocument25 pagesThe Appellate Body of The WTO in The United States Ban On Shrimp and Shrimp Products-LibreCharlesLaffiteauNo ratings yet

- The Appellate Body of The WTO in The United States Ban On Shrimp and Shrimp Products-LibreDocument27 pagesThe Appellate Body of The WTO in The United States Ban On Shrimp and Shrimp Products-LibreCharlesLaffiteauNo ratings yet

- Why Have The Relatively Successful Attempts To Govern The World S Production of Chlorofluorocarbons Not Been Duplicated inDocument21 pagesWhy Have The Relatively Successful Attempts To Govern The World S Production of Chlorofluorocarbons Not Been Duplicated inCharlesLaffiteauNo ratings yet

- Why We Are Not Regulating CarbonDocument24 pagesWhy We Are Not Regulating CarbonCharlesLaffiteauNo ratings yet

- US Climate Change Policy OptionsDocument26 pagesUS Climate Change Policy OptionsCharlesLaffiteauNo ratings yet

- Rio de Janeiro Climate Change Case StudyDocument22 pagesRio de Janeiro Climate Change Case StudyCharlesLaffiteauNo ratings yet

- Multinational Corporations: Making Dollars (And Sense) by Showing Respect For Environmental, Human and Labor Rights IssuesDocument17 pagesMultinational Corporations: Making Dollars (And Sense) by Showing Respect For Environmental, Human and Labor Rights IssuesCharlesLaffiteauNo ratings yet

- What Counter-Terrorism Strategies Characterize A Constructive and Cost-Effective Response To Al Qaeda-Inspired Terrorism?Document26 pagesWhat Counter-Terrorism Strategies Characterize A Constructive and Cost-Effective Response To Al Qaeda-Inspired Terrorism?CharlesLaffiteauNo ratings yet

- The Balloon Effect: The Failure of Supply Side Strategies in The War On DrugsDocument18 pagesThe Balloon Effect: The Failure of Supply Side Strategies in The War On DrugsCharlesLaffiteauNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Load Lifting Certification TrainingDocument13 pagesLoad Lifting Certification TrainingThaira VargasNo ratings yet

- Cbse Class 10 Syllabus 2019 20 Social Science PDFDocument14 pagesCbse Class 10 Syllabus 2019 20 Social Science PDFAnil KumarNo ratings yet

- The Enhancement of Shore EquipmentDocument2 pagesThe Enhancement of Shore EquipmentÓranNo ratings yet

- Berry Systems Warehousing Industrial Commercial BrochureDocument17 pagesBerry Systems Warehousing Industrial Commercial BrochureNabil AttaNo ratings yet

- 002zaxis 200 - Test Kinerja & Pemecahan MasalahDocument1 page002zaxis 200 - Test Kinerja & Pemecahan MasalahfajardiniantNo ratings yet

- 8b.packaging & Material Handling-2Document16 pages8b.packaging & Material Handling-2madhuroza5169No ratings yet

- M L 1 8 0 E 2 8 R I G I D 4 X 2: Dimensions (MM)Document2 pagesM L 1 8 0 E 2 8 R I G I D 4 X 2: Dimensions (MM)abd alkaderNo ratings yet

- EMB-145-Weight and BalanceDocument45 pagesEMB-145-Weight and BalanceChamchissojuTV 참치쏘주TVNo ratings yet

- John Deere Tractor Operators Manual 2840 Tractor 3130 Tractor PDFDocument7 pagesJohn Deere Tractor Operators Manual 2840 Tractor 3130 Tractor PDFMariana ToledoNo ratings yet

- MAN Engines - Portrait - ENDocument34 pagesMAN Engines - Portrait - ENOveis DarvishiNo ratings yet

- PORT AND TERMINAL MANAGEMENTDocument59 pagesPORT AND TERMINAL MANAGEMENTMANI MARAN RK100% (1)

- 2.9a Plant Equipment - Bulldozer ChecklistDocument2 pages2.9a Plant Equipment - Bulldozer ChecklistNoel OlivarNo ratings yet

- Captiva 2.4 CajaDocument3 pagesCaptiva 2.4 CajaHERNAN DARIO ZAPATA BUSTAMANTE100% (1)

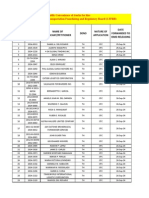

- Certificate of Public Convenience (Trucks For Hire) As of Oct - 9 - 2014Document65 pagesCertificate of Public Convenience (Trucks For Hire) As of Oct - 9 - 2014PortCallsNo ratings yet

- Facility Codes for Airport InfrastructureDocument15 pagesFacility Codes for Airport InfrastructureBilal SarhanNo ratings yet

- OEDocument1 pageOEJuse CoreNo ratings yet

- Paper 05Document21 pagesPaper 05mehul da aviatorNo ratings yet

- Magazine - Old - Cars - Weekly - 26 - March - 2020Document58 pagesMagazine - Old - Cars - Weekly - 26 - March - 2020robertoNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Introduction To EstimationDocument6 pagesUnit 1 Introduction To EstimationNidhi Mehta100% (1)

- Japan ItineraryDocument52 pagesJapan ItineraryRissa VargasNo ratings yet

- Diagrama Elétrico F-250Document153 pagesDiagrama Elétrico F-250Bruno Ayres de AbreuNo ratings yet

- 6511 FillDocument2 pages6511 FillEdward RudnevNo ratings yet

- Cat 745Document28 pagesCat 745Imam TL100% (1)

- Rail Transit Minimum Headway SimulationDocument11 pagesRail Transit Minimum Headway SimulationSidney RiveraNo ratings yet

- Tourism Research Title DefDocument17 pagesTourism Research Title DefKysha JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Abu Dhabi Transportation Impact Study GuidelinesDocument211 pagesAbu Dhabi Transportation Impact Study GuidelinesAsmaa AyadNo ratings yet

- Operational Suitability Data (OSD) Flight Crew: Cessna Aircraft Company Cessna Citation C560 XL / XLS / XLS+Document14 pagesOperational Suitability Data (OSD) Flight Crew: Cessna Aircraft Company Cessna Citation C560 XL / XLS / XLS+Vincent Lefeuvre100% (1)

- Team Game Job RiddlesDocument1 pageTeam Game Job RiddlesClases MendaviaNo ratings yet

- Grab Drive Digital Transformation JourneyDocument18 pagesGrab Drive Digital Transformation JourneyShayan ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Schedule Appointment - Firestone Complete Auto CareDocument2 pagesSchedule Appointment - Firestone Complete Auto CareSai BodduNo ratings yet