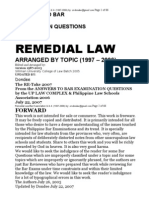

Professional Documents

Culture Documents

CD Presidency

Uploaded by

RAINBOW AVALANCHE0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

36 views47 pagesPetitioner was receiving a per diem for every board meeting he attended. COA disallowed the payment pursuant to the Supreme Court ruling. Petitioner contended that the Supreme Court modified its earlier ruling in the Civil Liberties Union case.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentPetitioner was receiving a per diem for every board meeting he attended. COA disallowed the payment pursuant to the Supreme Court ruling. Petitioner contended that the Supreme Court modified its earlier ruling in the Civil Liberties Union case.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

36 views47 pagesCD Presidency

Uploaded by

RAINBOW AVALANCHEPetitioner was receiving a per diem for every board meeting he attended. COA disallowed the payment pursuant to the Supreme Court ruling. Petitioner contended that the Supreme Court modified its earlier ruling in the Civil Liberties Union case.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 47

1

Bitonio vs. COA

Post under case digests, Political Law at Friday, March 09, 2012 Posted by Schizophrenic Mind

Facts: In 1994, petitioner Benedicto Ernesto

R. Bitonio, Jr. was appointed Director IV of

the Bureau of Labor Relations in the

Department of Labor and Employment. As

representative of the Secretary of Labor to

the PEZA Board, he was receiving a per

diem for every board meeting he attended

during the years 1995 to 1997.

After a post audit of the PEZAs

disbursement transactions, the COA

disallowed the payment of per diems to Mr.

Bitonio pursuant to the Supreme Court ruling

declaring unconstitutional the holding of

other offices by the cabinet members, their

deputies and assistants in addition to their

primary office and the receipt of

compensation therefore, and, to COA

Memorandum No. 97-038 dated September

19, 1997, implementing Senate Committee

Reports No. 509.

In his motion for reconsideration to the COA,

he contended that the Supreme Court

modified its earlier ruling in the Civil Liberties

Union case which limits the prohibition to

Cabinet Secretaries, Undersecretaries and

their Assistants. Officials given the rank

equivalent to a Secretary, Undersecretary or

Assistant Secretary and other appointive

officials below the rank of Assistant

Secretary are not covered by the prohibition.

He further stated that the PEZA Charter (RA

7916), enacted four years after the Civil

Liberties Union case became final,

authorized the payment of per diems; in

expressly authorizing per diems, Congress

should be conclusively presumed to have

been aware of the parameters of the

constitutional prohibition as interpreted in the

Civil Liberties Union case.

COA rendered the assailed decision denying

petitioners motion for reconsideration.

2

Issue: Whether COA correctly disallowed

the per diems received by the petitioner for

his attendance in the PEZA Board of

Directors meetings as representative of the

Secretary of Labor.

Held: The assailed decision of the COA is

affirmed.

The petitioner is, indeed, not entitled to

receive per diem for his board meetings

sitting as representative of the Secretary of

Labor in the Board of Directors of the PEZA.

The petitioners presence in the PEZA Board

meetings is solely by virtue of his capacity as

representative of the Secretary of Labor.

Since the Secretary of Labor is prohibited

from receiving compensation for his

additional office or employment, such

prohibition likewise applies to the petitioner

who sat in the Board only in behalf of the

Secretary of Labor. The Supreme Court

cannot allow the petitioner who sat as

representative of the Secretary of Labor in

the PEZA Board to have a better right than

his principal.

Moreover, it is a basic tenet that any

legislative enactment must not be repugnant

to the Constitution. No law can render it

nugatory because the Constitution is more

superior to a statute. The framers of R.A. No.

7916 must have realized the flaw in the law

which is the reason why the law was later

amended by R.A. No. 8748 to cure such

defect. The option of designating

representative to the Board by the different

Cabinet Secretaries was deleted. Likewise,

the paragraph as to payment of per diems to

the members of the Board of Directors was

also deleted, considering that such

stipulation was clearly in conflict with the

proscription set by the Constitution.

3

Dennis B. Funa vs. Executive Secretary

Eduardo R. Ermita, Office of the

President,G.R. No. 184740, February 11, 2010.

Post under Political Law, villarama doctrines at Monday, November 28, 2011 Posted

by Schizophrenic Mind

Judicial review; requisites. The

courts power of judicial review, like almost

all other powers conferred by the

Constitution, is subject to several limitations,

namely: (1) there must be an actual case or

controversy calling for the exercise of judicial

power; (2) the person challenging the act

must have standing to challenge; he must

have a personal and substantial interest in

the case, such that he has sustained or

will sustain, direct injury as a result of its

enforcement; (3) the question of

constitutionality must be raised at the earliest

possible opportunity; and (4) the issue of

constitutionality must be the very lis mota of

the case. Respondents assert that the

second requisite is absent in this case.

Generally, a party will be allowed

to litigate only when (1) he can

show that he has personally

suffered some actual or

threatened injury because of the

allegedly illegal conduct of the

government; (2) the injury is fairly

traceable to the challenged action;

and (3) the injury is likely to be

redressed by a favorable action.

The question on standing is

whether such parties have

alleged such a personal stake in

the outcome of the controversy

as to assure that concrete

adverseness which sharpens the

presentation of issues upon

which the court so largely

4

depends for illumination of

difficult constitutional questions.

In David v. Macapagal-Arroyo,

summarizing the rules culled from

jurisprudence, the Supreme

Court held that taxpayers, voters,

concerned citizens, and

legislators may be accorded

standing to sue, provided that the

following requirements are met:

(1) cases involve constitutional

issues;

(2) for taxpayers, there must be a

claim of illegal disbursement of

public funds or that the tax

measure is unconstitutional;

(3) for voters, there must be a

showing of obvious interest in the

validity of the election law in

question;

(4) for concerned citizens, there

must be a showing that the

issues raised are of transcendental

importance which must be settled

early; and for legislators, there

must be a claim that the official

action complained of infringes

upon their prerogatives as

legislators.

5

Petitioner having alleged a grave

violation of the constitutional

prohibition against Members of

the Cabinet, their deputies and

assistants holding two (2) or

more positions in government, the fact

that he filed this suit as a

concerned citizen sufficiently

confers him with standing to sue

for redress of such illegal act by

public officials.

Public officials; multiple

office. The prohibition against holding

dual or multiple offices or employment under

Section 13, Article VII of the 1987

Constitution was held inapplicable to posts

occupied by the Executive officials specified

therein, without additional compensation in

an ex-officio capacity as provided by law and

as required by the primary functions of said

office. The reason is that these posts do not

comprise any other office within the

contemplation of the constitutional

prohibition but are properly an imposition of

additional duties and functions on said

officials. Apart from their bare assertion that

respondent Bautista did not receive any

compensation when she was OIC of

MARINA, respondents failed to demonstrate

clearly that her designation as such OIC was

in an ex-officio capacity as required by the

primary functions of her office as DOTC

Undersecretary for Maritime Transport.

Given the vast responsibilities

and scope of administration of

the MARINA, we are hardly

persuaded by respondents

submission that respondent

Bautistas designation as OIC of

6

MARINA was merely an

imposition of additional duties

related to her primary position as

DOTC Undersecretary for

Maritime Transport. It appears

that the DOTC Undersecretary

for Maritime Transport is not even

a member of the Maritime

Industry Board, which includes

the DOTC Secretary as

Chairman, the MARINA

Administrator as Vice-Chairman,

and the following as members:

Executive Secretary (Office of the

President), Philippine Ports

Authority General Manager,

Department of National Defense

Secretary, Development Bank of

the Philippines General Manager,

and the Department of Trade and

Industry Secretary.

It must be stressed though that

while the designation was in the

nature of an acting and

temporary capacity, the words

hold the office were employed.

Such holding of office pertains to

both appointment and

designation because the

appointee or designate performs

the duties and functions of the

office. The 1987 Constitution in

prohibiting dual or multiple offices,

as well as incompatible offices,

refers to the holding of the office,

and not to the nature of the

appointment or designation,

7

words which were not even found

in Section 13, Article VII nor in

Section 7, paragraph 2, Article

IX-B. To hold an office means to

possess or occupy the same, or

to be in possession and administration,

which implies nothing less than

the actual discharge of the

functions and duties of the office.

The disqualification laid down in

Section 13, Article VII is aimed

at preventing the concentration of

powers in the Executive

Department officials, specifically

the President, Vice-President,

Members of the Cabinet and their

deputies and assistants.Civil

Liberties Union traced the history of

the times and the conditions

under which the Constitution was

framed, and construed the

Constitution consistent with the

object sought to be accomplished

by adoption of such provision,

and the evils sought to be

avoided or remedied. We recalled

the practice, during the Marcos

regime, of designating members

of the Cabinet, their deputies and

assistants as members of the

governing bodies or boards of

various government agencies

and instrumentalities, including

government-owned or controlled

corporations. This practice of

holding multiple offices

or positions in the government

8

led to abuses by unscrupulous

public officials, who took

advantage of this scheme for

purposes of self-enrichment. The

blatant betrayal of public trust

evolved into one of the serious

causes of discontent with the

Marcos regime. It was therefore

quite inevitable and in

consonance with the

overwhelming sentiment of the

people that the 1986

Constitutional Commission would

draft into the proposed

Constitution the provisions under

consideration, which were

envisioned to remedy, if not

correct, the evils that flow from

the holding of multiple

governmental offices and

employment.Dennis B. Funa vs.

Executive Secretary Eduardo R.

Ermita, Office of the

President,G.R. No. 184740,

February 11, 2010.

G. R. No. 85468, September 07, 1989

DOROMA VS. SANDIGANBAYAN, Om

budsman and Special Prosecutor

FACTS:

Quintin S. Doromal, a former Commissioner of the Presidential Commission

on Good Government (PCGG), for violation of the Anti-Graft and Corrupt

Practices Act (RA 3019), Sec. 3(h), in connection with his shareholdings and

position as president and director of the Doromal International Trading

Corporation (DITC) which submitted bids to supply P61 million worth of

electronic, electrical, automotive, mechanical and airconditioning equipment

to the Department of Education, Culture and Sports (or DECS) and the

National Manpower and Youth Council (or NMYC).

An information was then filed by the Tanodbayan against Doromal for the

said violation and a preliminary investigation was conducted.

The petitioner then filed a petition for certiorari and prohibition questioning

the jurisdiction of the Tanodbayan to file the information without the

approval of the Ombudsman.

The Supreme Court held that the incumbent Tanodbayan (called Special

Prosecutor under the 1987 Constitution and who is supposed to retain

powers and duties NOT GIVEN to the Ombudsman) is clearly without

authority to conduct preliminary investigations and to direct the filing of

criminal cases with the Sandiganbayan, except upon orders of the

9

Ombudsman. Subsequently annulling the information filed by the

Tanodbayan.

A new information, duly approved by the Ombudsman, was filed in the

Sandiganbayan, alleging that the Doromal, a public officer, being then a

Commissioner of the Presidential Commission on Good Government, did

then and there wilfully and unlawfully, participate in a business through the

Doromal International Trading Corporation, a family corporation of which he

is the President, and which company participated in the biddings conducted

by the Department of Education, Culture and Sports and the National

Manpower & Youth Council, which act or participation is prohibited by law

and the constitution.

The petitioner filed a motion to quash the information on the ground that it

was invalid since there had been no preliminary investigation for the new

information that was filed against him.

The motion was denied by Sandiganbayan claiming that another preliminary

investigation is unnecessary because both old and new informations involve

the same subject matter.

ISSUES:

Whether or not the act of Doromal would constitute a violation of the Constitution.

Whether or not preliminary investigation is necessary even if both informations

involve the same subject matter.

Whether or not the information shall be effected as invalid due to the absence of

preliminary investigation.

HELD:

Yes, as to the first and second issuses. No, as to the third issue. Petition was

granted by the Supreme Court.

RATIO:

(1) The presence of a signed document bearing the signature of Doromal as

part of the application to bid shows that he can rightfully be charged with

having participated in a business which act is absolutely prohibited by

Section 13 of Article VII of the Constitution" because "the DITC remained a

family corporation in which Doromal has at least an indirect interest."

Section 13, Article VII of the 1987 Constitution provides that "the President,

Vice-President, the members of the Cabinet and their deputies or assistants

shall not... during (their) tenure, ...directly or indirectly... participate in any

business.

(2) The right of the accused to a preliminary investigation is "a substantial

one." Its denial over his opposition is a "prejudicial error, in that it subjects

the accused to the loss of life, liberty, or property without due process of law"

provided by the Constitution.

Since the first information was annulled, the preliminary investigation

conducted at that time shall also be considered as void. Due to that fact, a

new preliminary investigation must be conducted.

(3) The absence of preliminary investigation does not affect the court's

jurisdiction over the case. Nor do they impair the validity of the information or

otherwise render it defective; but, if there were no preliminary investigations

and the defendants, before entering their plea, invite the attention of the

court to their absence, the court, instead of dismissing the information should

conduct such investigation, order the fiscal to conduct it or remand the case

to the inferior court so that the preliminary investigation may be conducted.

WHEREFORE, the petition for certiorari and prohibition is granted. The

Sandiganbayan shall immediately remand Criminal Case No. 12893 to the

Office of the Ombudsman for preliminary investigation and shall hold in

abeyance the proceedings before it pending the result of such investigation.

ARTURO M. DE CASTRO vs.

JUDICIAL AND BAR COUNCIL (JBC)

G. R. No. 191002. March 17, 2010.

FACTS:

This case is based on multiple cases field with dealt with the

controversy that has arisen from the forthcoming compulsory

requirement of Chief Justice Puno on May 17, 2010 or seven days

after the presidential election. On December 22, 2009,

Congressman Matias V. Defensor, an ex officio member of the

JBC, addressed a letter to the JBC, requesting that the process

for nominations to the office of the Chief Justice be commenced

10

immediately. In its January 18, 2010 meeting en banc, the JBC

passed a resolution which stated that they have unanimously

agreed to start the process of filling up the position of Chief

Justice to be vacated on May 17, 2010 upon the retirement of the

incumbent Chief Justice. As a result, the JBC opened the position

of Chief Justice for application or recommendation, and published

for that purpose its announcement in the Philippine Daily Inquirer

and the Philippine Star. In its meeting of February 8, 2010, the

JBC resolved to proceed to the next step of announcing the

names of the following candidates to invite to the public to file their

sworn complaint, written report, or opposition, if any, not later than

February 22, 2010. Although it has already begun the process for

the filling of the position of Chief Justice Puno in accordance with

its rules, the JBC is not yet decided on when to submit to the

President its list of nominees for the position due to the

controversy in this case being unresolved. The compiled cases

which led to this case and the petitions of intervenors called for

either the prohibition of the JBC to pass the shortlist, mandamus

for the JBC to pass the shortlist, or that the act of appointing the

next Chief Justice by GMA is a midnight appointment. A precedent

frequently cited by the parties is the In Re Appointments Dated

March 30, 1998 of Hon. Mateo A. Valenzuela and Hon. Placido B.

Vallarta as Judges of the RTC of Branch 62, Bago City and of

Branch 24, Cabanatuan City, respectively, shortly referred to here

as the Valenzuela case, by which the Court held that Section 15,

Article VII prohibited the exercise by the President of the power to

appoint to judicial positions during the period therein fixed.

ISSUES:

1. Whether or not the petitioners have legal standing.

2. Whether or not there is justiciable controversy that is ripe for

judicial determination.

3. Whether or not the incumbent President can appoint the next

Chief Justice.

4. Whether or not mandamus and prohibition will lie to compel the

submission of the shortlist of nominees by the JBC.

HELD:

1.Petitioners have legal standing because such requirement for

this case was waived by the Court. Legal standing is a peculiar

concept in constitutional law because in some cases, suits are not

brought by parties who have been personally injured by the

operation of a law or any other government act but by concerned

citizens, taxpayers or voters who actually sue in the public

interest. But even if, strictly speaking, the petitioners are not

covered by the definition, it is still within the wide discretion of the

Court to waive the requirement and so remove the impediment to

its addressing and resolving the serious constitutional questions

raised.

11

2. There is a justiciable issue. The court holds that the petitions

set forth an actual case or controversy that is ripe for judicial

determination. The reality is that the JBC already commenced the

proceedings for the selection of the nominees to be included in a

short list to be submitted to the President for consideration of

which of them will succeed Chief Justice Puno as the next Chief

Justice. Although the position is not yet vacant, the fact that the

JBC began the process of nomination pursuant to its rules and

practices, although it has yet to decide whether to submit the list

of nominees to the incumbent outgoing President or to the next

President, makes the situation ripe for judicial determination,

because the next steps are the public interview of the candidates,

the preparation of the short list of candidates, and the interview of

constitutional experts, as may be needed. The resolution of the

controversy will surely settle with finality the nagging questions

that are preventing the JBC from moving on with the process that

it already began, or that are reasons persuading the JBC to desist

from the rest of the process.

3.Prohibition under section 15, Article VII does not apply to

appointments to fill a vacancy in the Supreme Court or to other

appointments to the judiciary. The records of the deliberations of

the Constitutional Commission reveal that the framers devoted

time to meticulously drafting, styling, and arranging the

Constitution. Such meticulousness indicates that the organization

and arrangement of the provisions of the Constitution were not

arbitrarily or whimsically done by the framers, but purposely made

to reflect their intention and manifest their vision of what the

Constitution should contain. As can be seen, Article VII is devoted

to the Executive Department, and, among others, it lists the

powers vested by the Constitution in the President. The

presidential power of appointment is dealt with in Sections 14, 15

and 16 of the Article. Had the framers intended to extend the

prohibition contained in Section 15, Article VII to the appointment

of Members of the Supreme Court, they could have explicitly done

so. They could not have ignored the meticulous ordering of the

provisions. They would have easily and surely written the

prohibition made explicit in Section 15, Article VII as being equally

applicable to the appointment of Members of the Supreme Court

in Article VIII itself, most likely in Section 4 (1), Article VIII.

4.Writ of mandamus does not lie against the JBC. Mandamus

shall issue when any tribunal, corporation, board, officer or person

unlawfully neglects the performance of an act that the law

specifically enjoins as a duty resulting from an office, trust, or

station. It is proper when the act against which it is directed is one

addressed to the discretion of the tribunal or officer. Mandamus is

not available to direct the exercise of a judgment or discretion in a

particular way. For mandamus to lie, the following requisites must

be complied with: (a) the plaintiff has a clear legal right to the act

demanded; (b) it must be the duty of the defendant to perform the

act, because it is mandated by law; (c) the defendant unlawfully

neglects the performance of the duty enjoined by law; (d) the act

to be performed is ministerial, not discretionary; and (e) there is no

appeal or any other plain, speedy and adequate remedy in the

ordinary course of law.

12

Bermudez vs Torres

2 Comments

GR No. 131429, August 4, 1999

FACTS:

The vacancy in the Office of the Provincial Prosecutor of Tarlac impelled the

main contestants in this case, petitioner Oscar Bermudez and respondent Conrado

Quiaoit, to take contrasting views on the proper interpretation of a provision in

the 1987 Revised Administrative Code. Bermudez was a recommendee of then

Justice Secretary Teofisto Guingona, Jr., for the position of Provincial Prosecutor.

Quiaoit, on the other hand, had the support of then Representative Jose Yap. On

30 June 1997, President Ramos appointed Quiaoit to the coveted office. Quiaoit

received a certified xerox copy of his appointment and, on 21 July 1997, took his

oath of office before Executive Judge Angel Parazo of the Regional Trial Court

(Branch 65) of Tarlac, Tarlac. On 23 July 1997, Quiaoit assumed office and

immediately informed the President, as well as the Secretary of Justice and the

Civil Service Commission, of that assumption.

On 10 October 1997, Bermudez filed with the Regional Trial Court of Tarlac, a

petition for prohibition and/or injunction, and mandamus, with a prayer for the

issuance of a writ of injunction/temporary restraining order, against herein

respondents, challenging the appointment of Quiaoit primarily on the ground that

the appointment lacks the recommendation of the Secretary of Justice prescribed

under the Revised Administrative Code of 1987. After hearing, the trial court

considered the petition submitted for resolution and, in due time, issued its now

assailed order dismissing the petition. The subsequent move by petitioners to

have the order reconsidered met with a denial.

ISSUE:

Whether or not the absence of a recommendation of the Secretary of Justice to

the President can be held fatal to the appointment of respondent Conrado Quiaoit.

HELD:

The petition is denied. An appointment to a public office is the unequivocal act

of designating or selecting by one having the authority therefor of an individual

to discharge and perform the duties and functions of an office or trust. The

appointment is deemed complete once the last act required of the appointing

authority has been complied with and its acceptance thereafter by the appointee

in order to render it effective.

Indeed, it may rightly be said that the right of choice is the heart of the power to

appoint. In the exercise of the power of appointment, discretion is an integral part

thereof.

When the Constitution or the law clothes the President with the power to appoint

a subordinate officer, such conferment must be understood as necessarily

carrying with it an ample discretion of whom to appoint. It should be here

pertinent to state that the President is the head of government whose authority

includes the power of control over all executive departments, bureaus and

offices.

It is the considered view of the Court that the phrase upon recommendation of

the Secretary, found in Section 9, Chapter II, Title III, Book IV, of the Revised

Administrative Code, should be interpreted to be a mere advise, exhortation or

indorsement, which is essentially persuasive in character and not binding or

obligatory upon the party to whom it is made. The President, being the head of

the Executive Department, could very well disregard or do away with the action

of the departments, bureaus or offices even in the exercise of discretionary

authority, and in so opting, he cannot be said as having acted beyond the scope of

his authority.

13

Pimentel vs. Ermita

Post under case digests, Political Law at Friday, March 09, 2012 Posted by Schizophrenic Mind

Facts: This is a petition to declare

unconstitutional the appointments issued by

President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo

(President Arroyo) through Executive

Secretary Eduardo R. Ermita (Secretary

Ermita) to Florencio B. Abad, Avelino J.

Cruz, Jr., Michael T. Defensor, Joseph H.

Durano, Raul M. Gonzalez, Alberto G.

Romulo, Rene C. Villa, and Arthur C. Yap

(respondents) as acting secretaries of their

respective departments.

On August 2004, Arroyo issued

appointments to respondents as acting

secretaries of their respective departments.

Congress adjourned on 22 September 2004.

On 23 September 2004, President Arroyo

issued ad interim appointments to

respondents as secretaries of the

departments to which they were previously

appointed in an acting capacity.

Issue: Is President Arroyos appointment of

respondents as acting secretaries without

the consent of the Commission on

Appointments while Congress is in session,

constitutional?

Held: Yes. The power to appoint is

essentially executive in nature, and the

legislature may not interfere with the

exercise of this executive power except in

those instances when the Constitution

expressly allows it to interfere. Limitations on

the executive power to appoint are construed

strictly against the legislature. The scope of

the legislatures interference in the

executives power to appoint is limited to the

power to prescribe the qualifications to an

appointive office. Congress cannot appoint a

person to an office in the guise of prescribing

qualifications to that office. Neither may

Congress impose on the President the duty

to appoint any particular person to an office.

14

However, even if the Commission on

Appointments is composed of members of

Congress, the exercise of its powers is

executive and not legislative. The

Commission on Appointments does not

legislate when it exercises its power to give

or withhold consent to presidential

appointments.

Petitioners contend that President Arroyo

should not have appointed respondents as

acting secretaries because in case of a

vacancy in the Office of a Secretary, it is only

an Undersecretary who can be designated

as Acting Secretary.

The essence of an appointment in an acting

capacity is its temporary nature. It is a stop-

gap measure intended to fill an office for a

limited time until the appointment of a

permanent occupant to the office. In case of

vacancy in an office occupied by an alter ego

of the President, such as the office of a

department secretary, the President must

necessarily appoint an alter ego of her

choice as acting secretary before the

permanent appointee of her choice could

assume office.

Congress, through a law, cannot impose on

the President the obligation to appoint

automatically the undersecretary as her

temporary alter ego. An alter ego, whether

temporary or permanent, holds a position of

great trust and confidence. Congress, in the

guise of prescribing qualifications to an office,

cannot impose on the President who her

alter ego should be.

The office of a department secretary may

become vacant while Congress is in session.

Since a department secretary is the alter ego

of the President, the acting appointee to the

office must necessarily have the Presidents

confidence. Thus, by the very nature of the

office of a department secretary, the

President must appoint in an acting capacity

a person of her choice even while Congress

15

is in session. That person may or may not be

the permanent appointee, but practical

reasons may make it expedient that the

acting appointee will also be the permanent

appointee.

The law expressly allows the President to

make such acting appointment. Section 17,

Chapter 5, Title I, Book III of EO 292 states

that [t]he President may temporarily

designate an officer already in the

government service or any other competent

person to perform the functions of an office

in the executive branch. Thus, the President

may even appoint in an acting capacity a

person not yet in the government service, as

long as the President deems that person

competent.

Finally, petitioners claim that the issuance of

appointments in an acting capacity is

susceptible to abuse. Petitioners fail to

consider that acting appointments cannot

exceed one year as expressly provided in

Section 17(3), Chapter 5, Title I, Book III of

EO 292. The law has incorporated this

safeguard to prevent abuses, like the use of

acting appointments as a way to circumvent

confirmation by the Commission on

Appointments.

Ad-interim appointments must be

distinguished from appointments in an acting

capacity. Both of them are effective upon

acceptance. But ad-interim appointments are

extended only during a recess of Congress,

whereas acting appointments may be

extended any time there is a vacancy.

Moreover ad-interim appointments are

submitted to the Commission on

Appointments for confirmation or rejection;

acting appointments are not submitted to the

Commission on Appointments. Acting

appointments are a way of temporarily filling

important offices but, if abused, they can

also be a way of circumventing the need for

confirmation by the Commission on

Appointments.

16

However, we find no abuse in the present

case. The absence of abuse is readily

apparent from President Arroyos issuance

of ad interim appointments to respondents

immediately upon the recess of Congress,

way before the lapse of one year.

Flores v Drilon (223 SCRA 568)

Posted by Evelyn

FACTS:

The constitutionality of Sec. 13, par. (d), of R.A. 7227,

otherwise known as the "Bases

Conversion and Development Act of 1992," under which respondent Mayor Richard J.

Gordon of Olongapo City was appointed Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of the

Subic Bay Metropolitan Authority (SBMA), is challenged with prayer for prohibition,

preliminary injunction and temporary restraining order. Said provision provides the

President the power to appoint an administrator of the SBMA provided that in the first

year of its operation, the Olongapo mayor shall be appointed as chairman and chief of

executive of the Subic Authority. Petitioners maintain that such infringes to the

constitutional provision of Sec. 7, first par., Art. IX-B, of the Constitution, which states

that "no elective official shall be eligible for appointment or designation in any capacity

to any public officer or position during his tenure," The petitioners also contend that

Congress encroaches upon the discretionary power of the President to appoint.

ISSUE:

Whether or not said provision of the RA 7227 violates the constitutional prescription

against appointment or designation of elective officials to other government posts.

RULING:

The court held the Constitution seeks to prevent a public officer to hold multiple

functions since they are accorded with a public office that is a full time job to let them

function without the distraction of other governmental duties.

The Congress gives the President the appointing authority which it cannot limit by

providing the condition that in the first year of the operation the Mayor of Olongapo

City shall assume the Chairmanship. The court points out that the appointing authority

the congress gives to the President is no power at all as it curtails the right of the

President to exercise discretion of whom to appoint by limiting his choice.

DENR VS DENR EMPLOYEES

Posted by kaye lee on 12:43 PM

G.R. No. 149724 [Alter ego of the President, Qualified Political Agency Doctrine]

FACTS:

DENR Reg 12 Employees filed a petition for nullity of the memorandum order issued by

the Regional Exec. Director of DENR, directing the immediate transfer of the DENR 12

Regional Offices from Cotabato to Koronadal City. The memorandum was issued

pursuant to DENR Executive Order issued by the DENR Secretary.

Issue:

Whether or not DENR Secretary has the authority to reorganize the DENR Region 12

Office.

17

RULING: The qualified political agency doctrine, all executive and administrative

organizations are adjuncts of the Executive Department, and the acts of the Secretaries of

such departments, performed and promulgated in the regular course of business, are,

unless disapproved or reprobated by the Chief Executive, are presumptively the acts of

the Chief Executive. It is corollary to the control power of the President as provided for

under Art. VII Sec. 17 of the 1987 Constitution: "The President shall have control of all

the executive departments, bureaus, and offices. He shall ensure that the laws be

faithfully executed."

In the case at bar, the DENR Secretary can validly reorganize the DENR by ordering the

transfer of the DENR XII Regional Offices from Cotabato City to Koronadal, South

Cotabato. The exercise of this authority by the DENR Secretary, as an alter ego, is

presumed to be the acts of the President for the latter had not expressly repudiated the

same.

Categories: Constitutional Law 1, G.R. No. 149724

Hutchison Ports Philippines Limited (HPPL) v Subic Bay Metropolitan

Authority

Facts

Petition to suspend or hold in abeyance the conduct of SBMA of a rebidding.

SBMA advertised an invitation offering to the private sector the opportunity to

develop andoperate a modern marine container terminal within Subic Bay

Freeport Zone.

Out of 7 bidders, 3 were declared as qualified: 1) ICTSI 2) RPSI and 3) HPPL

SBMA-PBAC first awarded to HPPL. However, ICTSI filed an appeal with SBMA

and alsobefore the Office of the President.

In a memorandum, the President ordered SBMA Chairman Gordon to revaluate

thefinancial bids together with the COA.

Again, the SBMA Board issued another reso declaring that HPPL is selected as

winner,since it has a realistic business plan offering the greatest financial return

to SBMA and themost advantageous to the government.

Nothwithstanding the SBMAs board recommendations, then Exec Sec Reuben

Torressubmitted a memorandum to the Office of President recommending

another rebidding.Consequently, the Office of Pres. Issued a memorandum to

conduct a rebidding.

On July 7, 1997, HPPL filed a complaint against SBMA before the RTC and

alleged that abinding and legally enforeceable contract had been established

between HPPL and SBMAunder Article 1305 of the civil code, considering that

SBMA had repeatedly declared andconfirmed that HPPL was the winning bidder.

During the pre-trial hearing, one of the issues raised and submitted for reso was

whetheror not the Office of the President can set aside the award made by

SBMA in favor of HPPLand if so, can the Office of the President direct the SBMA

to conduct re-bidding of theproposed

project.Issue: Can the President set aside the award made by SBMA in favor of H

PPL? If so, canthe Office of the President direct SBMA to conduct rebidding of

the proposedproject?Held:

Yes

HPPL has not sufficiently shown that it a has a clear and unmistakable right to be

declaredthe winning bidder. Though SBMA Board of Directors may have

declared them as winner,said award is not final and unassailable.

The SBMA Board of Directors are subject to the control and supervision of the

President.All projects undertaken by SBMA require the approval of the President

under Letters of Instruction No. 620

Letters of Instruction No. 620 mandates that the approval of the President is

required in allcontracts of the national government offices, agencies and

instrumentalities includingGOCCS involving P2M and above, awarded through

public bidding or negotiation.

The President may, within his authority, overturn or reverse any award made by

the SBMABoard of Directors for justifiable reasons.

When the President issued the memorandum setting a side the award previously

declaredby SBMA in favor of HPPL, the same was within authority of the

President and was a validexercise of his prerogative.

18

The petition is dismissed for lack of merit.

KMU vs. NEDA GR no. 167798

April 19, 2006

KMU vs. NEDA , GR no. 167798 , April 19, 2006

FACTS:

In April 13, 2005, President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo issued Executive

Order 420 requiring all government agencies and government-owned

corporations to streamline and harmonize their Identification Systems.

The purposes of the uniform ID data collection and ID format are to

reduce costs, achieve efficiency and reliability and ensure compatibility

and provide convenience to the people served by government entities.

Petitioners allege that EO420 is unconstitutional because it constitutes

usurpation of legislative functions by the executive branch of the

government. Furthermore, they allege that EO420 infringes on the

citizens rights to privacy.

ISSUE: In issuing EO 420, did the president make, alter or repeal any

laws?

RULING:

Legislative power is the authority to make laws and to alter or repeal them.

In issuing EO 420, the President did not make, alter or repeal any law but

merely implemented and executed existing laws. EO 420 reduces costs, as

well as insures efficiency, reliability, compatibility and user-friendliness

in the implementation of current ID systems of government entities under

existing laws. Thus, EO 420 is simply an executive issuance and not an act

of legislation.

Angeles vs. Gaite

Facts

1. Petitioner was given custody of her grand niece, Maria Mercedes Vistan, to take

care and provide for as she grew up. Petitioner became attached to such child and

took care of her as her own. Petitioner also gave the same attention to the half-

brother of the grand niece. The latter would seek petitioners financial support

ranging from daily subsistence to hospitalization expenses.

2. After one incident wherein the half-brother of the grand niece, Michael Vistan,

failed to do an important task, the petitioner and the Michael Vistan had a falling

out. Since no more support was given to the latter, he took his half-sister away. He

brought her to different provinces while asked the help of certain individuals to

mislead the petitioner and the police.

3. The police was able to apprehend Michael Vistan through a dragnet operation.

4. The petitioner filed a complaint against Michael Vistan before the Office of the

Provincial Prosecutor in Malolos, Bulacan for five counts of Violation of Section 10

(a), Article VI of RA 7610, otherwise known as the Child Abuse Act, and for four

counts of Violation of Sec. 1 (e) of PD 1829. She likewise filed a complaint for Libel

against Maria Cristina Vistan, aunt of Michael and Maria Mercedes.

5. The Investigating prosecutor issued a resolution to continue with the filing of the

case. This was however denied by the provincial prosecutor who also issued a

decision to dismiss the case. Petitioner filed a petition for review with USEC.

Teehankee but was denied. Petitioner then filed a petition for review with SEC

Perez and was also denied

6. She tried appealing to the Office of the President but was dismissed by such on the

ground of Memorandum Circular No. 58 which bars an appeal or a petition for

review of decisions/orders/resolutions of the Secretary of Justice except those

involving offenses punishable by reclusion perpetua or death

7. Petitioner went to the CA which sustained the dismissal

8. Petitioner contends that such Memo Circular was unconstitutional since t

diminishes the power of control of the President and bestows upon the Secretary

of Justice, a subordinate officer, almost unfettered power.

Issue

W/N Memorandum Circular No. 58 is unconstitutional since it diminishes the power of

the President?

Ruling

NO, it does not diminish the power of the President

The President's act of delegating authority to the Secretary of Justice by virtue of said

Memorandum Circular is well within the purview of the doctrine of qualified political agency, long

been established in our jurisdiction.

Under this doctrine, which primarily recognizes the establishment of a single executive, "all

executive and administrative organizations are adjuncts of the Executive Department; the heads

of the various executive departments are assistants and agents of the Chief Executive; and, except

in cases where the Chief Executive is required by the Constitution or law to act in person or the

exigencies of the situation demand that he act personally, the multifarious executive and

administrative functions of the Chief Executive are performed by and through the executive

departments, and the acts of the secretaries of such departments, performed and promulgated in

the regular course of business, are, unless disapproved or reprobated by the Chief Executive,

presumptively the acts of the Chief Executive."The CA cannot be deemed to have committed any

error in upholding the Office of the President's reliance on the Memorandum Circular as it merely

interpreted and applied the law as it should be.

19

Memorandum Circular No. 58, promulgated by the Office of the President on June 30, 1993 reads:

In the interest of the speedy administration of justice, the guidelines

enunciated in Memorandum Circular No. 1266 (4 November 1983) on the

review by the Office of the President of resolutions/orders/decisions issued by

the Secretary of Justice concerning preliminary investigations of criminal cases

are reiterated and clarified.

No appeal from or petition for review of decisions/orders/resolutions of the

Secretary of Justice on preliminary investigations of criminal cases shall be

entertained by the Office of the President, except those involving offenses

punishable by reclusion perpetua to death x x x.

Henceforth, if an appeal or petition for review does not clearly fall within the

jurisdiction of the Office of the President, as set forth in the immediately

preceding paragraph, it shall be dismissed outright x x x.

It is quite evident from the foregoing that the President himself set the limits of his power to

review decisions/orders/resolutions of the Secretary of Justice in order to expedite the disposition

of cases. Petitioner's argument that the Memorandum Circular unduly expands the power of the

Secretary of Justice to the extent of rendering even the Chief Executive helpless to rectify

whatever errors or abuses the former may commit in the exercise of his discretion is purely

speculative to say the least. Petitioner cannot second- guess the President's power and the

President's own judgment to delegate whatever it is he deems necessary to delegate in order to

achieve proper and speedy administration of justice, especially that such delegation is upon a

cabinet secretary his own alter ego.

BUT THERE ARE LIMITATIONS:

Justice Jose P. Laurel, in his ponencia in Villena, makes this clear that

There are certain constitutional powers and prerogatives of the

Chief Executive of the Nation which must be exercised by him in person and

no amount of approval or ratification will validate the exercise of any of those

powers by any other person. Such, for instance, is his power to suspend the

writ of habeas corpus and proclaim martial law (par. 3, sec. 11, Art. VII) and

the exercise by him of the benign prerogative of mercy (par. 6, sec. 11, idem).

These restrictions hold true to this day as they remain embodied in our fundamental law.

There are certain presidential powers which arise out of exceptional circumstances, and if

exercised, would involve the suspension of fundamental freedoms, or at least call for the

supersedence of executive prerogatives over those exercised by co-equal branches of government.

The declaration of martial law, the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, and the exercise of

the pardoning power, notwithstanding the judicial determination of guilt of the accused, all fall

within this special class that demands the exclusive exercise by the President of the

constitutionally vested power. The list is by no means exclusive, but there must be a showing that

the executive power in question is of similar gravitas and exceptional import.

In the case at bar, the power of the President to review the Decision of the Secretary of

Justice dealing with the preliminary investigation of cases cannot be considered as falling within

the same exceptional class which cannot be delegated. Besides, the President has not fully

abdicated his power of control as Memorandum Circular No. 58 allows an appeal if the imposable

penalty is reclusion perpetua or higher. Certainly, it would be unreasonable to impose upon the

President the task of reviewing all preliminary investigations decided by the Secretary of Justice.

To do so will unduly hamper the other important duties of the President by having to scrutinize

each and every decision of the Secretary of Justice notwithstanding the latters expertise in said

matter.

The Constitutional interpretation of the petitioner would negate the very existence of

cabinet positions and the respective expertise which the holders thereof are accorded and

would unduly hamper the Presidents effectivity in running the government.

Boy Scouts of the Philippines vs.

Commission on Audit, G.R. No. 177131. June

7, 2011.

Post under Political Law at Sunday, October 16, 2011 Posted by Schizophrenic Mind

Commission on Audit; jurisdiction over

Boy Scouts. (J . Abad)

The issue was whether or not the Boy

Scouts of the Philippines (BSP) fall under

the jurisdiction of the Commission on Audit.

The BSP contends that it is not a

government-owned or controlled corporation;

neither is it an instrumentality, agency, or

subdivision of the government. The Supreme

Court, however, held that not all corporations,

which are not government owned or

20

controlled, are ipso facto to be considered

private corporations as there exists another

distinct class of corporations or chartered

institutions which are otherwise known as

public corporations. These corporations are

treated by law as agencies or

instrumentalities of the government which

are not subject to the tests of ownership or

control and economic viability but to a

different criteria relating to their public

purposes/interests or constitutional policies

and objectives and their administrative

relationship to the government or any of its

departments or offices. As presently

constituted, the BSP is a public corporation

created by law for a public purpose, attached

to the Department of Education Culture and

Sports pursuant to its Charter and the

Administrative Code of 1987. It is not a

private corporation which is required to be

owned or controlled by the government and

be economically viable to justify its existence

under a special law. The economic viability

test would only apply if the corporation is

engaged in some economic activity or

business function for the government, which

is not the case for BSP. Therefore, being a

public corporation, the funds of the BSP fall

under the jurisdiction of the Commission on

Audit.

Drilon vs Lim

Leave a comment

GR No. 112497, August 4, 1994

FACTS:

Pursuant to Section 187 of the Local Government Code, the Secretary of Justice

had, on appeal to him of four oil companies and a taxpayer, declared Ordinance

No. 7794, otherwise known as the Manila Revenue Code, null and void for non-

compliance with the prescribed procedure in the enactment of tax ordinances and

for containing certain provisions contrary to law and public policy.

In a petition for certiorari filed by the City of Manila, the Regional Trial Court of

Manila revoked the Secretarys resolution and sustained the ordinance, holding

inter alia that the procedural requirements had been observed. More importantly,

it declared Section 187 of the Local Government Code as unconstitutional

because of its vesture in the Secretary of Justice of the power of control over

local governments in violation of the policy of local autonomy mandated in the

Constitution and of the specific provision therein conferring on the President of

the Philippines only the power of supervision over local governments. The court

cited the familiar distinction between control and supervision, the first being the

power of an officer to alter or modify or set aside what a subordinate officer had

done in the performance of his duties and to substitute the judgment of the former

for the latter, while the second is the power of a superior officer to see to it that

lower officers perform their functions is accordance with law.

ISSUES:

The issues in this case are

21

(1) whether or not Section 187 of the Local Government Code is unconstitutional;

and

(2) whether or not the Secretary of Justice can exercise control, rather than

supervision, over the local government

HELD:

The judgment of the lower court is reversed in so far as its declaration that

Section 187 of the Local Government Code is unconstitutional but affirmed the

said lower courts finding that the procedural requirements in the enactment of

the Manila Revenue Code have been observed.

Section 187 authorizes the Secretary of Justice to review only the

constitutionality or legality of the tax ordinance and, if warranted, to revoke it on

either or both of these grounds. When he alters or modifies or sets aside a tax

ordinance, he is not also permitted to substitute his own judgment for the

judgment of the local government that enacted the measure. Secretary Drilon did

set aside the Manila Revenue Code, but he did not replace it with his own version

of what the Code should be.

An officer in control lays down the rules in the doing of an act. It they are not

followed, he may, in his discretion, order the act undone or re-done by his

subordinate or he may even decide to do it himself. Supervision does not cover

such authority. The supervisor or superintendent merely sees to it that the rules

are followed, but he himself does not lay down such rules, nor does he have the

discretion to modify or replace them. In the opinion of the Court, Secretary

Drilon did precisely this, and no more nor less than this, and so performed an act

not of control but of mere supervision.

Regarding the issue on the non-compliance with the prescribed procedure in the

enactment of the Manila Revenue Code, the Court carefully examined every

exhibit and agree with the trial court that the procedural requirements have

indeed been observed. The only exceptions are the posting of the ordinance as

approved but this omission does not affect its validity, considering that its

publication in three successive issues of a newspaper of general circulation will

satisfy due process.

Aberca vs. Ver Case Digest L-69866

April 15, 1988

FACTS:

This case stems from alleged illegal searches and seizures and other violations

of the rights and liberties of plaintiffs by various intelligence units of the Armed

Forces of the Philippines, known as Task Force Makabansa (TFM) ordered by

General Fabian Ver "to conduct pre-emptive strikes against known communist-

terrorist (CT) underground houses in view of increasing reports about CT plans to

sow disturbances in Metro Manila," Plaintiffs allege, among others, that

complying with said order, elements of the TFM raided several places, employing

in most cases defectively issued judicial search warrants; that during these raids,

certain members of the raiding party confiscated a number of purely personal

items belonging to plaintiffs; that plaintiffs were arrested without proper warrants

issued by the courts; that for some period after their arrest, they were denied

visits of relatives and lawyers; that plaintiffs were interrogated in violation of their

rights to silence and counsel; that military men who interrogated them employed

threats, tortures and other forms of violence on them in order to obtain

incriminatory information or confessions and in order to punish them; that all

violations of plaintiffs constitutional rights were part of a concerted and deliberate

plan to forcibly extract information and incriminatory statements from plaintiffs

and to terrorize, harass and punish them, said plans being previously known to

and sanctioned by defendants.

Seeking to justify the dismissal of plaintiffs' complaint, the respondents postulate

the view that as public officers they are covered by the mantle of state immunity

from suit for acts done in the performance of official duties or function

22

ISSUE:whether the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus bars

a civil action for damages for illegal searches conducted by military personnel

and other violations of rights and liberties guaranteed under the Constitution. If

such action for damages may be maintained, who can be held liable for such

violations: only the military personnel directly involved and/or their superiors as

well.

RATIO DICIDENDI:

SC: We find respondents' invocation of the doctrine of state immunity from suit

totally misplaced. The cases invoked by respondents actually involved acts done

by officers in the performance of official duties written the ambit of their powers.

It may be that the respondents, as members of the Armed Forces of the

Philippines, were merely responding to their duty, as they claim, "to prevent or

suppress lawless violence, insurrection, rebellion and subversion" in accordance

with Proclamation No. 2054 of President Marcos, despite the lifting of martial law

on January 27, 1981, and in pursuance of such objective, to launch pre- emptive

strikes against alleged communist terrorist underground houses. But this cannot

be construed as a blanket license or a roving commission untramelled by any

constitutional restraint, to disregard or transgress upon the rights and liberties of

the individual citizen enshrined in and protected by the Constitution. The

Constitution remains the supreme law of the land to which all officials, high or low,

civilian or military, owe obedience and allegiance at all times.

Article 32 of the Civil Code which renders any public officer or employee or any

private individual liable in damages for violating the Constitutional rights and

liberties of another, as enumerated therein, does not exempt the respondents

from responsibility. Only judges are excluded from liability under the said article,

provided their acts or omissions do not constitute a violation of the Penal Code or

other penal statute.

We do not agree. We find merit in petitioners' contention that the suspension of

the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus does not destroy petitioners' right and

cause of action for damages for illegal arrest and detention and other violations

of their constitutional rights. The suspension does not render valid an otherwise

illegal arrest or detention. What is suspended is merely the right of the individual

to seek release from detention through the writ of habeas corpus as a speedy

means of obtaining his liberty.

Firstly, it is wrong to at the plaintiffs' action for damages 5 Section 1, Article 19. to

'acts of alleged physical violence" which constituted delict or wrong. Article 32

clearly specifies as actionable the act of violating or in any manner impeding or

impairing any of the constitutional rights and liberties enumerated therein, among

others

The complaint in this litigation alleges facts showing with abundant clarity and

details, how plaintiffs' constitutional rights and liberties mentioned in Article 32 of

the Civil Code were violated and impaired by defendants. The complaint speaks

of, among others, searches made without search warrants or based on irregularly

issued or substantially defective warrants; seizures and confiscation, without

proper receipts, of cash and personal effects belonging to plaintiffs and other

items of property which were not subversive and illegal nor covered by the

search warrants; arrest and detention of plaintiffs without warrant or under

irregular, improper and illegal circumstances; detention of plaintiffs at several

undisclosed places of 'safehouses" where they were kept incommunicado and

subjected to physical and psychological torture and other inhuman, degrading

and brutal treatment for the purpose of extracting incriminatory statements. The

complaint contains a detailed recital of abuses perpetrated upon the plaintiffs

violative of their constitutional rights.

Secondly, neither can it be said that only those shown to have participated

"directly" should be held liable. Article 32 of the Civil Code encompasses within

the ambit of its provisions those directly, as well as indirectly, responsible for its

violation.

The responsibility of the defendants, whether direct or indirect, is amply set forth

in the complaint. It is well established in our law and jurisprudence that a motion

to dismiss on the ground that the complaint states no cause of action must be

based on what appears on the face of the complaint.

6

To determine the

sufficiency of the cause of action, only the facts alleged in the complaint, and no

others, should be considered.

7

For this purpose, the motion to dismiss

must hypothetically admit the truth of the facts alleged in the complaint.

8

IBP VS ZAMORA

Posted by kaye lee on 11:27 PM

G.R. No. 141284 August 15 2000 [Judicial Review; Civilian supremacy clause]

23

FACTS:

Invoking his powers as Commander-in-Chief under Sec 18, Art. VII of the Constitution,

President Estrada, in verbal directive, directed the AFP Chief of Staff and PNP Chief to

coordinate with each other for the proper deployment and campaign for a temporary

period only. The IBP questioned the validity of the deployment and utilization of the

Marines to assist the PNP in law enforcement.

ISSUE:

1. WoN the President's factual determination of the necessity of calling the armed forces

is subject to judicial review.

2. WoN the calling of AFP to assist the PNP in joint visibility patrols violate the

constitutional provisions on civilian supremacy over the military.

RULING:

1. The power of judicial review is set forth in Section 1, Article VIII of the Constitution,

to wit:

Section 1. The judicial power shall be vested in one Supreme Court and in such lower

courts as may be established by law.

Judicial power includes the duty of the courts of justice to settle actual controversies

involving rights which are legally demandable and enforceable, and to determine whether

or not there has been grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction

on the part of any branch or instrumentality of the Government.

When questions of constitutional significance are raised, the Court can exercise its power

of judicial review only if the following requisites are complied with, namely: (1) the

existence of an actual and appropriate case; (2) a personal and substantial interest of the

party raising the constitutional question; (3) the exercise of judicial review is pleaded at

the earliest opportunity; and (4) the constitutional question is the lis mota of the case.

2. The deployment of the Marines does not constitute a breach of the civilian supremacy

clause. The calling of the Marines in this case constitutes permissible use of military

assets for civilian law enforcement. The participation of the Marines in the conduct of

joint visibility patrols is appropriately circumscribed. It is their responsibility to direct

and manage the deployment of the Marines. It is, likewise, their duty to provide the

necessary equipment to the Marines and render logistical support to these soldiers. In

view of the foregoing, it cannot be properly argued that military authority is supreme

over civilian authority. Moreover, the deployment of the Marines to assist the PNP does

not unmake the civilian character of the police force. Neither does it amount to an

insidious incursion of the military in the task of law enforcement in violation of Section

5(4), Article XVI of the Constitution.

Lacson Vs. Perez Case Digest

Lacson Vs. Perez

357 SCRA 756 G.R. No. 147780

May 10, 2001

24

Facts: President Macapagal-Arroyo declared a State of Rebellion (Proclamation

No. 38) on May 1, 2001 as well as General Order No. 1 ordering the AFP and the

PNP to suppress the rebellion in the NCR. Warrantless arrests of several alleged

leaders and promoters of the rebellion were thereafter effected. Petitioner filed

for prohibition, injunction, mandamus and habeas corpus with an application for

the issuance of temporary restraining order and/or writ of preliminary injunction.

Petitioners assail the declaration of Proc. No. 38 and the warrantless arrests

allegedly effected by virtue thereof. Petitioners furthermore pray that the

appropriate court, wherein the information against them were filed, would desist

arraignment and trial until this instant petition is resolved. They also contend that

they are allegedly faced with impending warrantless arrests and unlawful

restraint being that hold departure orders were issued against them.

Issue: Whether or Not Proclamation No. 38 is valid, along with the warrantless

arrests and hold departure orders allegedly effected by the same.

Held: President Macapagal-Arroyo ordered the lifting of Proc. No. 38 on May 6,

2006, accordingly the instant petition has been rendered moot and academic.

Respondents have declared that the Justice Department and the police

authorities intend to obtain regular warrants of arrests from the courts for all acts

committed prior to and until May 1, 2001. Under Section 5, Rule 113 of the Rules

of Court, authorities may only resort to warrantless arrests of persons suspected

of rebellion in suppressing the rebellion if the circumstances so warrant, thus the

warrantless arrests are not based on Proc. No. 38. Petitioners prayer for

mandamus and prohibition is improper at this time because an individual

warrantlessly arrested has adequate remedies in law: Rule 112 of the Rules of

Court, providing for preliminary investigation, Article 125 of the Revised Penal

Code, providing for the period in which a warrantlessly arrested person must be

delivered to the proper judicial authorities, otherwise the officer responsible for

such may be penalized for the delay of the same. If the detention should have no

legal ground, the arresting officer can be charged with arbitrary detention, not

prejudicial to claim of damages under Article 32 of the Civil Code. Petitioners

were neither assailing the validity of the subject hold departure orders, nor were

they expressing any intention to leave the country in the near future. To declare

the hold departure orders null and void ab initio must be made in the proper

proceedings initiated for that purpose. Petitioners prayer for relief regarding their

alleged impending warrantless arrests is premature being that no complaints

have been filed against them for any crime, furthermore, the writ of habeas

corpus is uncalled for since its purpose is to relieve unlawful restraint which

Petitioners are not subjected to.

Petition is dismissed. Respondents, consistent and congruent with their

undertaking earlier adverted to, together with their agents, representatives, and

all persons acting in their behalf, are hereby enjoined from arresting Petitioners

without the required judicial warrants for all acts committed in relation to or in

connection with the May 1, 2001 siege of Malacaang.

ARTHUR D. LIM vs. HON. EXECUTIVE

SECRETARY (G.R. No. 151445) Case Digest

Facts:

Arthur D. Lim and Paulino P. Ersando filed a petition for certiorari and prohibition

attacking the constitutionality of Balikatan-02-1. They were subsequently joined

by SANLAKAS and PARTIDO NG MANGGAGAWA, both party-list organizations,

who filed a petition-in-intervention. Lim and Ersando filed suits in their capacities

as citizens, lawyers and taxpayers. SANLAKAS and PARTIDO on the other hand,

claimed that certain members of their organization are residents of Zamboanga

and Sulu, and hence will be directly affected by the operations being conducted

in Mindanao.

The petitioners alleged that Balikatan-02-1 is not covered by the Mutual

Defense Treaty (MDT) between the Philippines and the United States. Petitioners

posited that the MDT only provides for mutual military assistance in case of

armed attack by an external aggressor against the Philippines or the US.

Petitioners also claim that the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) does not

authorize American Soldiers to engage in combat operations in Philippine

Territory.

25

Issue:

Is the Balikatan-02-1 inconsistent with the Philippine Constitution?

Ruling:

The MDT is the core of the defense relationship between the Philippines and the

US and it is the VFA which gives continued relevance to it. Moreover, it is the

VFA that gave legitimacy to the current Balikatan exercise.

The constitution leaves us no doubt that US Forces are prohibited from engaging

war on Philippine territory. This limitation is explicitly provided for in the Terms of

Reference of the Balikatan exercise. The issues that were raised by the

petitioners was only based on fear of future violation of the Terms of Reference.

Based on the facts obtaining, the Supreme court find that the holding of

Balikatan-02-1 joint military exercise has not intruded into that penumbra of

error that would otherwise call for the correction on its part.

The petition and the petition-in-intervention is DISMISSED.

SANLAKAS Vs. Executive Secretary Case Digest

SANLAKAS Vs. Executive Secretary

421 SCRA 656 G.R. No. 159085

February 3, 2004

Facts: During the wee hours of July 27, 2003, some three-hundred junior officers

and enlisted men of the AFP, acting upon instigation, command and direction of

known and unknown leaders have seized the Oakwood Building in Makati.

Publicly, they complained of the corruption in the AFP and declared their

withdrawal of support for the government, demanding the resignation of the

President, Secretary of Defense and the PNP Chief. These acts constitute a

violation of Article 134 of the Revised Penal Code, and by virtue of Proclamation

No. 427 and General Order No. 4, the Philippines was declared under the State

of Rebellion. Negotiations took place and the officers went back to their barracks

in the evening of the same day. On August 1, 2003, both the Proclamation and

General Orders were lifted, and Proclamation No. 435, declaring the Cessation of

the State of Rebellion was issued.

In the interim, however, the following petitions were filed: (1) SANLAKAS AND

PARTIDO NG MANGGAGAWA VS. EXECUTIVE SECRETARY, petitioners

contending that Sec. 18 Article VII of the Constitution does not require the

declaration of a state of rebellion to call out the AFP, and that there is no factual

basis for such proclamation. (2)SJS Officers/Members v. Hon. Executive

Secretary, et al, petitioners contending that the proclamation is a circumvention

of the report requirement under the same Section 18, Article VII, commanding

the President to submit a report to Congress within 48 hours from the

proclamation of martial law. Finally, they contend that the presidential issuances

cannot be construed as an exercise of emergency powers as Congress has not

delegated any such power to the President. (3) Rep. Suplico et al. v. President

Macapagal-Arroyo and Executive Secretary Romulo, petitioners contending that

there was usurpation of the power of Congress granted by Section 23 (2), Article

VI of the Constitution. (4) Pimentel v. Romulo, et al, petitioner fears that the

declaration of a state of rebellion "opens the door to the unconstitutional

implementation of warrantless arrests" for the crime of rebellion.

26

Issue:

Whether or Not Proclamation No. 427 and General Order No. 4 are

constitutional?

Whether or Not the petitioners have a legal standing or locus standi to bring

suit?

Held: The Court rendered that the both the Proclamation No. 427 and General

Order No. 4 are constitutional. Section 18, Article VII does not expressly prohibit

declaring state or rebellion. The President in addition to its Commander-in-Chief

Powers is conferred by the Constitution executive powers. It is not disputed that

the President has full discretionary power to call out the armed forces and to

determine the necessity for the exercise of such power. While the Court may

examine whether the power was exercised within constitutional limits or in a

manner constituting grave abuse of discretion, none of the petitioners here have,

by way of proof, supported their assertion that the President acted without factual

basis. The issue of the circumvention of the report is of no merit as there was no

indication that military tribunals have replaced civil courts or that military

authorities have taken over the functions of Civil Courts. The issue of usurpation

of the legislative power of the Congress is of no moment since the President, in

declaring a state of rebellion and in calling out the armed forces, was merely

exercising a wedding of her Chief Executive and Commander-in-Chief powers.

These are purely executive powers, vested on the President by Sections 1 and

18, Article VII, as opposed to the delegated legislative powers contemplated by

Section 23 (2), Article VI. The fear on warrantless arrest is unreasonable, since

any person may be subject to this whether there is rebellion or not as this is a

crime punishable under the Revised Penal Code, and as long as a valid

warrantless arrest is present.

Legal standing or locus standi has been defined as a personal and substantial

interest in the case such that the party has sustained or will sustain direct injury

as a result of the governmental act that is being challenged. The gist of the

question of standing is whether a party alleges "such personal stake in the