Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Understanding Auditory Processing Disorders in Children

Uploaded by

Zhen JinxCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Understanding Auditory Processing Disorders in Children

Uploaded by

Zhen JinxCopyright:

Available Formats

Understanding Auditory Processing Disorders in

Children

by Teri James Bellis, PhD, CCC-A

In recent years, there has been a dramatic upsurge in professional and public awareness of

Auditory Processing Disorders (APD), also referred to as Central Auditory Processing Disorders

(CAPD). Unfortunately, this increase in awareness has resulted in a plethora of misconceptions and

misinformation, as well as confusion regarding just what is (and isn't) an APD, how APD is

diagnosed, and methods of managing and treating the disorder. The term auditory processing

often is used loosely by individuals in many different settings to mean many different things, and

the label APD has been applied (often incorrectly) to a wide variety of difficulties and disorders. As

a result, there are some who question the existence of APD as a distinct diagnostic entity and

others who assume that the term APD is applicable to any child or adult who has difficulty listening

or understanding spoken language. The purpose of this article is to clarify some of these key

issues so that readers are better able to navigate the jungle of information available on the subject

in professional and popular literature today.

Terminology and Definitions

In its very broadest sense, APD refers to how the central nervous system (CNS) uses auditory

information. However, the CNS is vast and also is responsible for functions such as memory,

attention, and language, among others. To avoid confusing APD with other disorders that can

affect a person's ability to attend, understand, and remember, it is important to emphasize that

APD is an auditory deficit that is not the result of other higher-order cognitive, language, or related

disorder.

There are many disorders that can affect a person's ability to understand auditory information. For

example, individuals with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) may well be poor

listeners and have difficulty understanding or remembering verbal information; however, their

actual neural processing of auditory input in the CNS is intact. Instead, it is the attention deficit

that is impeding their ability to access or use the auditory information that is coming in. Similarly,

children with autism may have great difficulty with spoken language comprehension. However, it is

the higher-order, global deficit known as autism that is the cause of their difficulties, not a specific

auditory dysfunction. Finally, although the terms language processing and auditory processing

sometimes are used interchangeably, it is critical to understand that they are not the same thing

at all.

For many children and adults with these disorders and others - including mental retardation and

sensory integration dysfunction - the listening and comprehension difficulties we often see are due

to the higher-order, more global or all-encompassing disorder and not to any specific deficit in the

neural processing of auditory stimuli per se. As such, it is not correct to apply the label APD to

these individuals, even if many of their behaviors appear very similar to those associated with

APD. In some cases, however, APD may co-exist with ADHD or other disorders. In those cases,

only careful and accurate diagnosis can assist in disentangling the relative effects of each.

Diagnosing APD

Children with APD may exhibit a variety of listening and related complaints. For example, they

may have difficulty understanding speech in noisy environments, following directions, and

discriminating (or telling the difference between) similar-sounding speech sounds. Sometimes they

may behave as if a hearing loss is present, often asking for repetition or clarification. In school,

children with APD may have difficulty with spelling, reading, and understanding information

presented verbally in the classroom. Often their performance in classes that don't rely heavily on

listening is much better, and they typically are able to complete a task independently once they

know what is expected of them. However, it is critical to understand that these same types of

symptoms may be apparent in children who do not exhibit APD. Therefore, we should always keep

in mind that not all language and learning problems are due to APD, and all cases of APD do not

lead to language and learning problems. APD cannot be diagnosed from a symptoms checklist. No

matter how many symptoms of APD a child may have, only careful and accurate diagnostics can

determine the underlying cause.

A multidisciplinary team approach is critical to fully assess and understand the cluster of problems

exhibited by children with APD. Thus, a teacher or educational diagnostician may shed light on

academic difficulties; a psychologist may evaluate cognitive functioning in a variety of different

areas; a speech-language pathologist may investigate written and oral language, speech, and

related capabilities; and so forth. Some of these professionals may actually use test tools that

incorporate the terms "auditory processing" or "auditory perception" in their evaluation, and may

even suggest that a child exhibits an "auditory processing disorder." Yet it is important to know

that, however valuable the information from the multidisciplinary team is in understanding the

child's overall areas of strength and weakness, none of the test tools used by these professionals

are diagnostic tools for APD, and the actual diagnosis of APD must be made by an audiologist.

To diagnose APD, the audiologist will administer a series of tests in a sound-treated room. These

tests require listeners to attend to a variety of signals and to respond to them via repetition,

pushing a button, or in some other way. Other tests that measure the auditory system's

physiologic responses to sound may also be administered. Most of the tests of APD require that a

child be at least 7 or 8 years of age because the variability in brain function is so marked in

younger children that test interpretation may not be possible.

Once a diagnosis of APD is made, the nature of the disorder is determined. There are many types

of auditory processing deficits and, because each child is an individual, APD may manifest itself in

a variety of ways. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the type of auditory deficit a given child

exhibits so that individualized management and treatment activities may be recommended that

address his or her specific areas of difficulty.

Treating APD

It is important to understand that there is not one, sure-fire, cure-all method of treating APD.

Notwithstanding anecdotal reports of "miracle cures" available in popular literature or on the

internet, treatment of APD must be highly individualized and deficit-specific. No matter how

successful a particular therapy approach may have been for another child, it does not mean that it

will be effective for your child. Therefore, the key to appropriate treatment is accurate and careful

diagnosis by an audiologist.

Treatment of APD generally focuses on three primary areas: changing the learning or

communication environment, recruiting higher-order skills to help compensate for the disorder,

and remediation of the auditory deficit itself. The primary purpose of environmental modifications

is to improve access to auditorily presented information. Suggestions may include use of electronic

devices that assist listening, teacher-oriented suggestions to improve delivery of information, and

other methods of altering the learning environment so that the child with APD can focus his or her

attention on the message.

Compensatory strategies usually consist of suggestions for assisting listeners in strengthening

central resources (language, problem-solving, memory, attention, other cognitive skills) so that

they can be used to help overcome the auditory disorder. In addition, many compensatory

strategy approaches teach children with APD to take responsibility for their own listening success

or failure and to be an active participant in daily listening activities through a variety of active

listening and problem-solving techniques.

Finally, direct treatment of APD seeks to remediate the disorder, itself. There exist a wide variety

of treatment activities to address specific auditory deficits. Some may be computer- assisted,

others may include one-on-one training with a therapist. Sometimes home-based programs are

appropriate whereas others may require children to attend therapy sessions in school or at a local

clinic. Once again, it should be emphasized that there is no one treatment approach that is

appropriate for all children with APD. The type, frequency, and intensity of therapy, like all aspects

of APD intervention, should be highly individualized and programmed for the specific type of

auditory disorder that is present.

The degree to which an individual child's auditory deficits will improve with therapy cannot be

determined in advance. Whereas some children with APD experience complete amelioration of

their difficulties or seem to "grow out of" their disorders, others may exhibit some residual degree

of deficit forever. However, with appropriate intervention, all children with APD can learn to

become active participants in their own listening, learning, and communication success rather than

hapless (and helpless) victims of an insidious impairment. Thus, when the journey is navigated

carefully, accurately, and appropriately, there can be light at the end of the tunnel for the millions

of children afflicted with APD.

Key Points:

APD is an auditory disorder that is not the result of higher-order, more global deficit such as

autism, mental retardation, attention deficits, or similar impairments.

Not all learning, language, and communication deficits are due to APD.

No matter how many symptoms of APD a child has, only careful and accurate diagnosis can

determine if APD is, indeed, present.

Although a multidisciplinary team approach is important in fully understanding the cluster of

problems associated with APD, the diagnosis of APD can only be made by an audiologist.

Treatment of APD is highly individualized. There is no one treatment approach that is

appropriate for all children with APD.

How We Hear

Parts of the Ear: Outer Ear | Middle Ear | Inner Ear

Hearing is one of the five senses. It is a complex

process of picking up sound and attaching meaning

to it. The ability to hear is critical to understanding

the world around us.

The human ear is a fully developed part of our bodies

at birth and responds to sounds that are very faint as

well as sounds that are very loud. Even before birth,

infants respond to sound.

So, how do we hear?

The ear can be divided into three parts leading up to the brain the outer ear, middle ear and

the inner ear.

The outer ear consists of the ear canal and eardrum. Sound travels down the ear canal,

striking the eardrum and causing it to move or vibrate.

The middle ear is a space behind the eardrum that contains three small bones called

ossicles. This chain of tiny bones is connected to the eardrum at one end and to an

opening to the inner ear at the other end. Vibrations from the eardrum cause the

ossicles to vibrate which, in turn, creates movement of the fluid in the inner ear.

Movement of the fluid in the inner ear, or cochlea, causes changes in tiny structures

called hair cells. This movement of the hair cells sends electric signals from the inner

ear up the auditory nerve (also known as the hearing nerve) to the brain.

The brain then interprets these electrical signals as sound

Degree of Hearing Loss

Degree of hearing loss refers to the severity of the loss. The table below shows one of the more

commonly used classification systems. The numbers are representative of the patient's hearing

loss range in decibels (dB HL).

Degree of hearing loss Hearing loss range (dB HL)

Normal 10 to 15

Slight 16 to 25

Mild 26 to 40

Moderate 41 to 55

Moderately severe 56 to 70

Severe 71 to 90

Profound 91+

Source: Clark, J. G. (1981). Uses and abuses of hearing loss classification. Asha, 23, 493500.

Hearing loss can be categorized by which part of the auditory system is damaged. There are three

basic types of hearing loss:

conductive hearing loss,

Conductive hearing loss occurs when sound is not conducted efficiently through the outer ear canal

to the eardrum and the tiny bones (ossicles) of the middle ear. Conductive hearing loss usually

involves a reduction in sound level or the ability to hear faint sounds. This type of hearing loss can

often be corrected medically or surgically.

Some possible causes of conductive hearing loss:

Fluid in the middle ear from colds

Ear infection (otitis media)

Allergies (serous otitis media)

Poor eustachian tube function

Perforated eardrum

Benign tumors

Impacted earwax (cerumen)

Infection in the ear canal (external otitis)

Presence of a foreign body

Absence or malformation of the outer ear, ear canal, or middle ear

sensorineural hearing loss,

Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) occurs when there is damage to the inner ear (cochlea), or to

the nerve pathways from the inner ear to the brain. Most of the time, SNHL cannot be medically or

surgically corrected. This is the most common type of permanent hearing loss.

SNHL reduces the ability to hear faint sounds. Even when speech is loud enough to hear, it may

still be unclear or sound muffled.

Some possible causes of SNHL:

Illnesses

Drugs that are toxic to hearing

Hearing loss that runs in the family (genetic or hereditary)

Aging

Head trauma

Malformation of the inner ear

Exposure to loud noise

and mixed hearing loss.

Sometimes a conductive hearing loss occurs in combination with a sensorineural hearing loss

(SNHL). In other words, there may be damage in the outer or middle ear and in the inner ear

(cochlea) or auditory nerve. When this occurs, the hearing loss is referred to as a mixed hearing

loss.

Classroom Acoustics

A student's ability to hear and understand what is being said in the classroom is vital for learning.

Unfortunately, this ability can be reduced in a noisy classroom. Poor classroom acoustics occur

when the background noise and/or the amount of reverberation in the classroom are so high that

they interfere with learning and teaching. We know that when classroom acoustics are poor then it

can affect

speech understanding

reading and spelling ability

behavior in the classroom

attention

concentration

academic achievement

What is background noise and reverberation?

Background noise is any unwanted sound that interferes with what you want to hear. Background

noise in a classroom can come from many sources such as traffic, lawnmowers, children on the

playground or in the hallway, heating or air conditioning units, audiovisual equipment, or other

students.

Reverberation refers to the phenomenon of sound continuing to be present in a room because of

sound reflecting off of surfaces such as desks or chairs. When sound lingers in a room there is

more interference with speech. In a classroom it is important to have a short reverberation time.

Who is affected by poor classroom acoustics?

All children are affected by poor classroom acoustics, but it can be a particular problem for children

with the following problems:

hearing loss, including children with a hearing loss in one ear (unilateral hearing loss)

temporary hearing loss in one or both ears (ear infection or build up of middle ear fluid)

learning disabilities

auditory processing disorders

speakers of another language

speech and language delay

attention problems

Poor classroom acoustics can also affect the teacher. It is estimated that teachers use their voices

for approximately 60% of their workday. The strain on the voice gets worse when the teacher has

to talk louder to overcome poor classroom acoustics. Studies have shown that teachers are 32

times more likely to have voice problems compared to similar occupations.

Creating an environment where good communication can take place should be a goal for any

classroom or learning space. Communication breaks down when the classroom acoustics are poor.

Reducing noise and reverberation in any space used for learning, such as community buildings,

home-based classrooms, and classrooms in places of worship, is important.

To learn about improving the acoustics in your classroom see Tips for Creating a Good Listening

Environment.

Tips for Creating a Good Listening Environment in the

Classroom

If your classroom is too noisy here are some simple tips to help make the environment quieter:

Place some rugs or carpet in the room if there none.

Hang window treatments such as curtains or blinds.

Hang soft materials such as felt or corkboard on the walls.

Place tables at an angle around the room to interfere with the pathways of sound.

Hang soft materials such as flags or student artwork around the room and from the ceiling.

Turn off noisy equipment when it is not in use.

Try to keep windows and doors closed when possible.

Replace noisy light fixtures.

Avoid open classrooms where many classes are taught in a large space.

Talk to the students about noise and demonstrate how it can be difficult to hear when many

children are talking at the same time.

Avoid dividing the class into groups where one group is listening to audiovisual equipment such

as the TV and the other group is listening to the teacher.

Remind visitors to the classroom that they should not be talking when the teacher is talking.

Place latex-free soft tips on the bottoms of chairs and tables. Do not use tennis balls to

dampen the sound! Tennis balls are made of latex which can cause allergic reactions in some

individuals. Also, mold can grow inside of the open tennis balls, which also poses a health risk.

Sports balls and materials free of latex are available from a variety of sources

ACUTE AND INTERMEDIATE PHASE NURSING IN TBI:

SENSORY-PERCEPTUAL, COMMUNICATION, AND

COGNITION DEFICITS

Sensory-Perceptual Deficits

1. Problems/Causes include deficits as a result of the injury in

vision, communication, and/or perception of self, body

image, illness, spatial relationships, agnosia, and apraxia

2. Nursing Diagnoses include:

o Perception of illness deficits, such as denial of

hemiplegia or other motor or sensory deficits and

anosognosia, the inability to recognize the denial or

unawareness of a deficit

o Body image disturbance, the patient's concept of the

sum of his/her body parts in relationship to the whole,

including unilateral neglect, the ignoring of the

hemiplegic side

o Sensory/perceptual alterations, such as:

Hemianopia (loss of vision in half of the

visual field) and defects in localizing objects

in space, estimating size, judging distances,

remembering arrangement of objects, finding

one's way to or back from places, telling time,

and right-hand discrimination

Agnosia, the inability to recognize familiar

objects with the senses

o Self-care deficit, such as apraxia, the inability to carry

out a learned, voluntary act in the absence of paralysis

3. Assessments include:

o Fails to use, shows a lack of concern for, lacks

awareness of or denies the part of the body involved

in hemiplegia or other motor or sensory deficits

o Draws an object and omits the side of the object that

corresponds to the affected side of the body

o Has difficulty walking through a doorway, exhibits

impaired recall of objects in a familiar environment,

has difficulty reading and computation, and is unable

to identify left or right

o Unable to identify common objects by sight or with

the eyes closed or to respond appropriately to

common sounds

o Exhibits clumsiness or an inability to carry out ADLs

correctly or to complete a task involving a sequence

of components

4. Nursing Interventions include:

o Accepting the patient's perception of, stimulating the

affected side or body part, teaching the patient to

position and care for the affected side or body part,

and positioning the affected side or part in the

patient's visual field

o Encouraging the patient to handle and use the affected

side or body part and teaching visual scanning and

other compensatory measures

o Providing verbal cues and instructions to the affected

side or body part

o Having the patient use other, intact senses to identify

stimuli or objects, teaching relearning via the drill

method, protecting the patient from injury, and

interpreting the patient's behavior for the family

o Encouraging participation in ADLs, correcting

mistakes or misuse of equipment, and reteaching

forgotten skills

Communication Deficits

1. Problems and Nursing Diagnoses - Aphasia in 1 of 3 forms:

o Nonfluent aphasia, the inability to express thoughts

verbally or in writing, can vary from mild to severe

o Fluent aphasia, the ability to hear, but not fully

comprehend speech, resulting in speech by the patient

that contains many errors and may be lengthy

o Global aphasia, a combination of expressive and

receptive aphasia in which little of the communication

system is left intact

2. Assessments

o Needs to search for words, chooses incorrect words

o Can communicate only by pointing, pantomime, etc.

3. Nursing Interventions include:

o Stimulating conversation, giving patient time to

search for words, disregarding incorrect words, and

generally supporting the patient's efforts to speak

o Accepting alternate forms of communication and

showing the patient pictures to permit communication

o Standing close so patient is aware of lip movements

o Speaking slowly and distinctly in a normal speaking

voice, using vocabulary or gestures the patient can

understand

o Anticipating the patient's needs

Cognitive Deficits

1. Problems/Nursing Diagnoses include:

o Shortened attention span and concentration, due to

diminished alertness, effort, and selection of stimuli

received

o Impaired judgment, due to decreased comprehension

and an inability to determine the consequences of

actions

o Impaired memory, both verbal and visual memory

o Initiation and sequencing problems

2. Assessments

o Inability to focus long enough to permit

understanding and appropriate response, and easily

distracted by external environmental factors

o Inability to take action in a safe and appropriate

manner

o Inability to retain information for 1 minute - 1 hour

(short-term memory) or for 1 hour or longer (long-

term memory)

o Inability to start a task and complete it from start to

finish

3. Nursing Interventions

o Attention: Reduce/minimize distractions, simply tasks

and procedures, allow ample time for task completion,

refocus attention as needed, avoid fatigue, provide

frequent verbal, visual, or tactile cues, and encourage

simple leisure activities

o Judgment: Allow patient to make simple decisions,

involve patient in other decision making processes,

and provide patient choices, ample time, and frequent

feedback

o Memory: Encourage use of memory aids, provide

clocks, calendars, radios and TVs, structure daily

exercises, post schedule/routine in a highly visible

place, and repeat and record new information as

needed for later review

o Initiate/sequence: Post daily schedule in a highly

visible place, break tasks into smaller steps, provide

cues for each step, allow patient to complete each

step, and provide supervision and support

Based on information in Hickey JV. The Clinical Practice of Neurological and Neurosurgical Nursing, 4th ed., Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1997 and in

Chin PA, et al. Rehabilitation Nursing Practice, N.Y.: McGraw-Hill, 1998, except for information where other papers are cited.

You might also like

- Waj3103 IslDocument5 pagesWaj3103 IslZhen JinxNo ratings yet

- Super ReportDocument8 pagesSuper ReportSameer GhuryeNo ratings yet

- Isl Week 11Document3 pagesIsl Week 11Zhen JinxNo ratings yet

- Isl 5Document4 pagesIsl 5Zhen JinxNo ratings yet

- Self Learning6Document4 pagesSelf Learning6Zhen JinxNo ratings yet

- Isl Week 9Document3 pagesIsl Week 9Zhen JinxNo ratings yet

- Isl 10 and 12Document5 pagesIsl 10 and 12Zhen JinxNo ratings yet

- ResourcesDocument13 pagesResourcesNajmi TajudinNo ratings yet

- Learning 2Document7 pagesLearning 2Zhen JinxNo ratings yet

- Real-Life Problem Using Theory of SetsDocument3 pagesReal-Life Problem Using Theory of SetsZhen JinxNo ratings yet

- How To Write A News Cast ScriptsDocument2 pagesHow To Write A News Cast ScriptsZhen JinxNo ratings yet

- Re FferenceDocument1 pageRe FferenceZhen JinxNo ratings yet

- WatDocument1 pageWatZhen JinxNo ratings yet

- HosannaDocument1 pageHosannaZhen JinxNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Bronfenbrenner S Ecological TheoryDocument24 pagesBronfenbrenner S Ecological TheoryJulie Anne BunaoNo ratings yet

- Edexcel GCSE Mathematics (Linear) – 1MA0 ALGEBRA: EXPAND & FACTORISEDocument8 pagesEdexcel GCSE Mathematics (Linear) – 1MA0 ALGEBRA: EXPAND & FACTORISETakayuki MimaNo ratings yet

- (AC-S05) Week 05 - Pre-Task - Quiz - Weekly Quiz - INGLES IV (11287)Document5 pages(AC-S05) Week 05 - Pre-Task - Quiz - Weekly Quiz - INGLES IV (11287)Enith AlzamoraNo ratings yet

- JDVP-TVL Program Billing StatementDocument2 pagesJDVP-TVL Program Billing StatementジナNo ratings yet

- NN Post Excursion Jacob Ballas 2014 t2Document3 pagesNN Post Excursion Jacob Ballas 2014 t2api-342873214No ratings yet

- Jesse Robredo Memorial BookDocument141 pagesJesse Robredo Memorial Bookannoying_scribd100% (1)

- Lesson Plan For Teaching WritingDocument7 pagesLesson Plan For Teaching WritingSaharudin YamatoNo ratings yet

- ReferencesDocument6 pagesReferencesPaula Jane LemoncitoNo ratings yet

- Context CLuesDocument17 pagesContext CLuesjes0009100% (1)

- Toning Revelation BookDocument35 pagesToning Revelation Bookmaicumotz100% (2)

- Cuban Visions 2011 ScribdDocument62 pagesCuban Visions 2011 ScribdCubanVisions100% (2)

- History of Nursing ProfessionDocument161 pagesHistory of Nursing ProfessionRashmi C SNo ratings yet

- VDC Final Project - Group3Document18 pagesVDC Final Project - Group3Aarav BalachandranNo ratings yet

- 2019-2020 Schola Application PDFDocument2 pages2019-2020 Schola Application PDFJane Limsan PaglinawanNo ratings yet

- Effective For The 2009-2010 School Year: School Uniform and Appearance PolicyDocument7 pagesEffective For The 2009-2010 School Year: School Uniform and Appearance Policyapi-250489050No ratings yet

- BS Artificial Intelligence Graduatoria Web Non-EU 2023-2024 Rettifica 14-06-2023 - PdfaDocument14 pagesBS Artificial Intelligence Graduatoria Web Non-EU 2023-2024 Rettifica 14-06-2023 - PdfayashbinladenNo ratings yet

- My Educational PhilosophyDocument6 pagesMy Educational PhilosophyRiza Grace Bedoy100% (1)

- 2022 IISMA Awards for Indonesian Students to Study AbroadDocument22 pages2022 IISMA Awards for Indonesian Students to Study AbroadRafli RidwanNo ratings yet

- Doing PhilosophyDocument71 pagesDoing Philosophyrheamay libo-onNo ratings yet

- Ventures3e SB Transitions3e U01Document15 pagesVentures3e SB Transitions3e U01محمد ٦No ratings yet

- Didactic Reduction: Literature Art Ancient Greek EducationDocument3 pagesDidactic Reduction: Literature Art Ancient Greek EducationEka PrastiyantoNo ratings yet

- SF Parish School 1st Grading Period ResultsDocument5 pagesSF Parish School 1st Grading Period ResultsShela may AntrajendaNo ratings yet

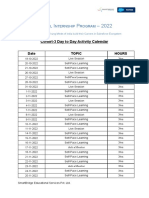

- Virtual Internship Program Activity CalendarDocument2 pagesVirtual Internship Program Activity Calendaranagha joshiNo ratings yet

- Unit Test - The Southwest Region: - /15 PointsDocument10 pagesUnit Test - The Southwest Region: - /15 Pointsapi-480186406No ratings yet

- Penulisan Rujukan Mengikut Format Apa Contoh PDFDocument16 pagesPenulisan Rujukan Mengikut Format Apa Contoh PDFzatty kimNo ratings yet

- Hoc Volume1Document46 pagesHoc Volume1nordurljosNo ratings yet

- Pembugaran EnglishDocument3 pagesPembugaran EnglishgomyraiNo ratings yet

- College Code College Name BranchDocument32 pagesCollege Code College Name BranchRaju DBANo ratings yet

- Heritage Tourism in IndiaDocument13 pagesHeritage Tourism in Indiavinay narneNo ratings yet

- Declaration: Engineering in Mechanical Engineering Under VISVESVARAYA TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY, BelgaumDocument4 pagesDeclaration: Engineering in Mechanical Engineering Under VISVESVARAYA TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY, BelgaumChandan KNo ratings yet