Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Delayed Hemothorax and Pericardial Tamponade Secondary To Stab Wounds To The Internal Mammary Artery PDF

Uploaded by

Rhenofkunair0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

35 views5 pagesMassive delayed hemothorax secondary to Stab Wounds to the internal mammary artery has been reported in only one study in the western literature. One of the patients had a combination of a delayed hemothorax and pericardial tamponade. Patients with parasternal injuries should be admitted to a telemetry unit, where thoracostomy tube outputs and vital signs can be monitored.

Original Description:

Original Title

Delayed Hemothorax and Pericardial Tamponade Secondary to Stab Wounds to the Internal Mammary Artery.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentMassive delayed hemothorax secondary to Stab Wounds to the internal mammary artery has been reported in only one study in the western literature. One of the patients had a combination of a delayed hemothorax and pericardial tamponade. Patients with parasternal injuries should be admitted to a telemetry unit, where thoracostomy tube outputs and vital signs can be monitored.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

35 views5 pagesDelayed Hemothorax and Pericardial Tamponade Secondary To Stab Wounds To The Internal Mammary Artery PDF

Uploaded by

RhenofkunairMassive delayed hemothorax secondary to Stab Wounds to the internal mammary artery has been reported in only one study in the western literature. One of the patients had a combination of a delayed hemothorax and pericardial tamponade. Patients with parasternal injuries should be admitted to a telemetry unit, where thoracostomy tube outputs and vital signs can be monitored.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

Case Study

Delayed Hemothorax and Pericardial

Tamponade Secondary to Stab Wounds

to the Internal Mammary Artery

Fausto Y. Vinces

1

274 European Journal of Trauma 2005 No. 3 Urban & Vogel

European Journal of Trauma

Ab stract

Background: Massive delayed hemothorax as a conse-

quence of stab wounds to the internal mammary artery

has been reported in only one study in the western liter-

ature.

Case Study: A review of patients who sustained injuries

to the parasternal region with internal mammary ar-

tery injuries is discussed. Three patients with injuries to

this structure that developed delayed a hemothorax

were identified. One of the patients had a combination

of a delayed hemothorax and pericardial tamponade.

All three patients were treated with emergency antero-

lateral thoracotomies.

Conclusion: Internal mammary artery injuries had a

high risk for the development of a delayed hemotho-

rax. Patients with parasternal injuries should be ad-

mitted to a telemetry unit, where thoracostomy tube

outputs and vital signs can be monitored continu-

ously. The addition of sonography to identify blood

in the pericardial sac and a lateral chest X-ray view to

rule out an extrapleural hematoma are useful and

should be considered in the management of these

patients.

Key Words

Internal mammary artery (IMA) Parasternal region

(PS) Hemothorax (HT) Thoracostomy tube (TT)

Eur J Trau ma 2005;31:2747

DOI 10.1007/s00068-005-1007-2

Introduction

Internal mammary artery injuries are usually secondary

to penetrating trauma to the precordial region. These

injuries are usually reported with other intrathoracic

vessel injuries. In the majority of patients who sustain

penetrating chest trauma, surgical intervention is per-

formed immediately after admission because of hemo-

dynamic instability or increased bloody output from a

thoracostomy tube. Delayed massive bleeding has been

described and is associated with a delayed hemothorax

that presents a few hours after placement of the thora-

costomy tube. A review of our trauma registry demon-

strated three patients who sustained stab wounds to the

parasternal area with internal mammary artery injuries

that developed a delayed hemothorax and in one case a

pericardial tamponade. These patients underwent im-

mediate exploratory thoracotomies with excellent re-

sults.

Case Study

Patient 1

A 21-year-old male sustained multiple stab wounds to

his right chest. His vital signs included a heart rate of 93

beats per minute (bpm), blood pressure of 138/73

mmHg, respirations of 20, and oxygen saturation of

98%. The patient had three stab wounds located in the

following areas: right second and fifth intercostal space

at the midclavicular line level with an open pneumotho-

rax and one to the fifth intercostal space 2 cm from the

sternum. A 36-F right chest tube was placed to relieve

1

Department of Surgery, Saint Barnabas Hospital, Bronx, NY, USA.

Received: June 9, 2004; revision accepted: November 26, 2004.

Vinces FY. Delayed Hemothorax Secondary to IMA Injuries

275 European Journal of Trauma 2005 No. 3 Urban & Vogel

his pneumothorax, and 300 cm

3

of blood drainage was

obtained after its insertion. Focused abdominal sono-

gram for trauma (FAST) was negative for pericardial

fluid. Postinsertion chest X-ray demonstrated the lung

expanded and without evidence of hemothorax. The pa-

tient was admitted to the intensive care unit, and 3 h

later the drainage of the chest tube started increasing to

175 cm

3

/h for the next 3 h with two episodes where the

systolic blood pressure decreased to 88 mmHg. Repeat

FAST was consistent with a pericardial effusion. The

patient was taken to the operating room for an emer-

gency thoracotomy that demonstrated a complete tran-

section of the right internal mammary artery with ap-

proximately 450 cm

3

of blood in the chest and 300 cm

3

of

blood in the pericardial sac causing a tamponade that

was relieved with a pericardiotomy. The right internal

mammary artery was ligated, and he was discharged on

postoperative day 7.

Patient 2

A 25-year-old male sustained a single stab wound to the

left parasternal region approximately 3 cm lateral from

the level of insertion of the fourth rib in the sternum.

His vital signs in the trauma bay were a heart rate of 102

bpm, blood pressure of 118/66 mmHg, respiratory rate

of 18, and a Glasgow Coma Score of 15. The patient un-

derwent the Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol

and a FAST exam that was negative for pericardial flu-

id. A chest X-ray demonstrated a left pneumothorax,

and a 36-F left chest tube was placed with immediate

relief from his pneumothorax. However, approximately

250 cm

3

of blood drainage was obtained after the inser-

tion. The repeat chest X-ray demonstrated a fully ex-

panded lung. In the next 3 h in the emergency depart-

ment the patient had one episode where his systolic

blood pressure decreased to 72 mmHg but responded to

1-l bolus of crystalloids. His chest tube drainage had in-

creased to 600 cm

3

for the last 3 h. It was decided to take

the patient to the operating room for a left anterolateral

thoracotomy that demonstrated 600 cm

3

of blood in the

left chest cavity with a complete transection of the left

anterior mammary artery and active bleeding into the

left thoracic cavity. The artery was ligated, and he was

discharged on postoperative day 5.

Patient 3

A 19-year-old male sustained two stab wounds to his right

parasternal region at the level of the third and fourth ribs.

On his arrival to the trauma bay his vital signs were a

heart rate of 100 bpm, blood pressure of 132/68 mmHg,

and respiratory rate of 20. The patient underwent the

Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol, FAST exam

and a chest X-ray that were negative for tamponade but

demonstrated a right pneumothorax. A 36-F thoracosto-

my tube was placed with expansion of the lung and 200

cm

3

of bloody drainage. The patient was admitted to the

telemetry unit where he had two episodes of hypotension

(systolic blood pressure of 82 mmHg). In addition, there

was an increased output from his thoracostomy tube to

approximately 750 cm

3

in 4 h. Due to these findings the

patient was taken to the operating room for a right an-

terolateral thoracotomy that demonstrated an injury to

the right internal mammary artery with 500 cm

3

of blood

on the right thoracic cavity. The artery was ligated, and

he was discharged on postoperative day 8.

Patients and Methods

A retrospective review of all stab wounds to the chest was

performed at St. Barnabas Hospital, a regional level I

trauma center in an urban setting in New York City,

USA. The trauma registry was used to identify patients

with this type of injury from June 2000 to May 2003. Their

records were reviewed, and the following data were re-

trieved: time of injury and surgical intervention, wound

location, chest tube insertion and output, chest X-ray film

reports, operative reports, structures injured, hospital

course, mortality and morbidity. Because of the anatomic

location of the internal mammary artery, stab wounds to

the parasternal region were identified. This region was

described as being below the clavicles, between the mid-

clavicular lines, and above the costal margins.

Results

94 patients with stab wounds to the chest were identi-

fied. 29 of these patients had wounds that were paraster-

nal in location. Two of these patients were noted to have

internal mammary artery injuries with delayed hemo-

thoraces and one with a combined presentation of a de-

layed hemothorax and a pericardial tamponade. De-

layed hemothorax occurred in all three patients within

8, 3 and 4 h, respectively, after placement of the thora-

costomy tube. Thoracostomy tubes were placed in all

patients with an initial output between 200 and 300 cm

3

of blood. None of the three patients had evidence of a

residual hemothorax after placement of the thoracos-

tomy tube. In addition, there was not change in vital

signs or thoracostomy tube outputs during the first hour

of admission. However, upon admission to the teleme-

Vinces FY. Delayed Hemothorax Secondary to IMA Injuries

276 European Journal of Trauma 2005 No. 3 Urban & Vogel

try unit, three patients had consistently episodes of hy-

potension that partially responded to crystalloid bolus-

es. The only remarkable finding on chest X-ray was a

right lower lobe contusion on patient 1.

Discussion

The internal mammary artery arises from the subclavian

artery directly and courses down the chest wall anterior

to the pleura and endothoracic fascia (Figure 1). The

artery distance varies from the lateral sternal margin

and usually terminates at the sixth intercostal space as

the musculophrenic and superior epigastric arteries.

The average diameter of the vessel is 2 mm, and com-

plete transection is the most common type of injury [1].

A completely transected vessel can potentially retract

and achieve hemostasis as a result of arterial spasm and

hypotension. However, this hemostasis can be disrupted

with aggressive resuscitation causing a delayed bleeding

that had been seen in three of our patients. Flow rates in

this blood vessel average 150 ml/m which can result in

massive hemothorax that can develop a few hours after

the injury [1].

Penetrating injuries to the chest are common and

usually require the placement of a thoracostomy tube to

relieve either a pneumothorax or hemothorax. Series

describing penetrating chest trauma had been published

in the literature, but most of them have not specifically

focused on injuries to the internal mammary artery and

its relationship to delayed hemothorax and in some cas-

es delayed pericardial tamponade [2]. Demetriades et

al. identified internal mammary artery injuries, but

there was not a delayed massive hemothorax that re-

quired surgical intervention [3].

The parasternal area was described as a potentially

dangerous zone by Siemens et al., and they recommend-

ed routine surgical exploration of this region [4]. How-

ever, most of their patients sustained gunshot and not

stab wounds. Ritter & Chang reported two mortalities

out of five patients, and both cases were associated with

a delayed hemothorax [1]. Their findings are consistent

with ours in that three of their patients did not have ini-

tial evidence of hemothorax but later developed signifi-

cant bleeding that required emergent intervention.

Our report confirms that stab wounds to the para-

sternal area should be treated with a high level of suspi-

cion even in hemodynamically stable patients. Internal

mammary artery injuries should be suspected, and if

there is a chest tube in place in these patients, drainage

should be monitored hourly. Our small series is unique

because all these patients were admitted to a telemetry

bed where their vital signs were closely monitored.

Therefore, the periods of hemodynamically instability

were recorded and acted upon immediately. Figure 2

demonstrates the algorithm used at our institution to

manage precordial stab wounds. The use of the FAST

exam to rule out pericardial fluid is an extremely impor-

tant part of the initial evaluation of these patients. A

positive result will require the patient to go to the oper-

ating room for exploration. A negative result will re-

Figure 1. Anatomic cross section of the internal mammary vessels and

surrounding structures, 119 79 mm (300 300 DPI).

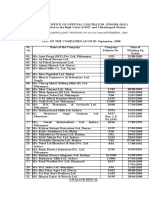

FAST positive

Operating room

Admit to telemetry unit

Record output every 1 h,

vital signs every 30 min

Admit to surgical floor

Repeat CXR in 6 h,

vital signs every 4 h

Hypotension < 90 mmHg

Refractory to fluid boluses with

tube output > 200 cm

3

blood/h 23 h

Operating room Tube removal when output

< 100 cm

3

/24 h

Discharge home after

24 h if second CXR

negative

Precordial stab wounds

FAST negative

Thoracostomy tube required

No

No

Yes

Yes

Figure 2. Management of precordial stab wounds.

Vinces FY. Delayed Hemothorax Secondary to IMA Injuries

277 European Journal of Trauma 2005 No. 3 Urban & Vogel

quire the patient to be admitted for a 24-h observation

period with a repeat two-view chest X-ray in 6 h. The

patient could be safely discharged after this period, if

the work-up is negative. However, if the patient has a

negative FAST but requires a tube thoracostomy, he/

she will be admitted to the telemetry unit where the vital

signs and thoracostomy outputs will be monitored. The

presence of hypotension (defined as a systolic blood

pressure < 90 mmHg), which is not responsive to crys-

talloid boluses, is an indicator that the patient may re-

quire immediate surgical intervention. This factor alone

or combined with increased output from the thoracos-

tomy tube (200 cm

3

of blood for 2 or 3 h) will indicate

the presence of a delayed hemothorax that will require

the patient to go to the operating room.

The exact etiology for the presence of a delayed he-

mothorax is not completely elucidated [5]. We had tried

to outline and describe three stages that explain the for-

mation of a delayed hemothorax. The first stage is the

transection of the vessel with a small laceration of the

pleura or pericardium with the creation of an extrapleu-

ral hematoma [6]. Figure 3 demonstrates the anatomic

landmarks and formation of the hematoma. This extra-

pleural hematoma can be seen as a pulmonary contu-

sion on the initial chest X-ray. The second stage is the

communication of this hematoma with the pleural cavi-

ty secondary to its increase in size and pressure. There is

evidence that small lacerations of the pleura occur dur-

ing this type of injury and that blood can leak into the

pleural cavity and pericardial sac creating a massive he-

mothorax or pericardial tamponade. In the third stage,

there will be an increase in output from the thoracosto-

my tube with hemodynamic instability. This clinical pre-

sentation will require an urgent thoracotomy to control

and ligate the bleeding vessel. Finally, in selected and

hemodynamically stable patients, embolization therapy

had been used as an alternative to thoracotomy in chest

wall trauma [7, 8].

Conclusion

As a result of these findings, our protocol includes a

FAST exam to examine the pericardium for blood. In

hemodynamically stable patients, a two-view chest

X-ray film or a computed tomography of the chest is

obtained to rule out an extrapleural hematoma. Finally,

admission to a monitored bed is recommended in order

to maintain an adequate vigilance over vital signs and

thoracostomy tube outputs.

References

1. Ritter DC, Chang FC. Delayed hemothorax resulting from stab

wound to the internal mammary artery. J Trauma 1995;39:5869.

2. Mandal AK, Oparah SS. Unusually low mortality of penetrating

wounds of the chest. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1989;97:11925.

3. Demetriades D, Rabinowitz B, Markides N. Indications for thora-

cotomy in stab injuries of the chest: a prospective study of 543

patients. Br J Surg 1986;73:88890.

4. Siemens R, Polk HC, Gray LA, et al. Indications for thoracotomy fol-

lowing penetrating thoracic injury. J Trauma 1977;17:493500.

5. Mohlala ML, Vanker EA, Ballaram RS. Internal mammary artery

haematoma. S Afr J Surg 1989;27:1368.

6. Curley SA, Demarest GB, Hauswald M. Pericardial tamponade and

hemothorax after penetrating injury to the internal mammary

artery. J Trauma 1986;27:9578.

7. Carrillo EH, Heniford BT, Senler SO, et al. Embolization therapy as

an alternative to thoracotomy in vascular injuries of the chest

wall. Am Surg 1998;64:11428.

8. Whigham CJ, Fisher RG, Goodman CJ, et al. Traumatic injury of the

internal mammary artery: embolization versus surgical and non-

operative management. Emerg Radiol 2002;9:2017.

Address for Correspondence

Fausto Y. Vinces, DO

Section of Trauma and Critical Care

Department of Surgery

Saint Barnabas Hospital

2nd Floor, Third Ave. and 183rd St.

Bronx, NY 10457

USA

Phone (+1/718) 960-6127, Fax -6132

e-mail: vincesf@optonline.net

Figure 3. Formation of

an extrapleural hema-

toma with hemothorax,

75 119 mm (300 300

DPI).

Reproducedwith permission of thecopyright owner. Further reproductionprohibited without permission.

You might also like

- Glomus TumorDocument6 pagesGlomus TumorRhenofkunairNo ratings yet

- CancerDocument8 pagesCancerRhenofkunairNo ratings yet

- Abdominal TuberculosisDocument7 pagesAbdominal TuberculosisArri KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Chest Stab Wound-Related Coronary Artery Pseudoaneurysm Sealed With A Polytetrafluoroethylene-Covered StentDocument4 pagesChest Stab Wound-Related Coronary Artery Pseudoaneurysm Sealed With A Polytetrafluoroethylene-Covered StentRhenofkunairNo ratings yet

- Florence-Sydney Breast Biopsy Study - Sensitivity of Ultrasound-Guided Versus Freehand Fine Needle Biopsy of Palpable Breast CancerDocument6 pagesFlorence-Sydney Breast Biopsy Study - Sensitivity of Ultrasound-Guided Versus Freehand Fine Needle Biopsy of Palpable Breast CancerRhenofkunairNo ratings yet

- Abdominal TBCDocument11 pagesAbdominal TBCNitin SainiNo ratings yet

- July 1991 B PDFDocument4 pagesJuly 1991 B PDFRhenofkunair0% (1)

- Abdominal TuberculosisDocument7 pagesAbdominal TuberculosisArri KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Mab200802 03 PDFDocument5 pagesMab200802 03 PDFRhenofkunairNo ratings yet

- Abdominal TuberculosisDocument7 pagesAbdominal TuberculosisArri KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Observation and Analysis Method of Human Bones (Page31-41)Document11 pagesObservation and Analysis Method of Human Bones (Page31-41)RhenofkunairNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of Gallbladder Disease Cholelithiasis and CancerDocument16 pagesEpidemiology of Gallbladder Disease Cholelithiasis and CancerRhenofkunairNo ratings yet

- Chest Stab Wound-Related Coronary Artery Pseudoaneurysm Sealed With A Polytetrafluoroethylene-Covered StentDocument4 pagesChest Stab Wound-Related Coronary Artery Pseudoaneurysm Sealed With A Polytetrafluoroethylene-Covered StentRhenofkunairNo ratings yet

- Clinical and Social Consequences of Buerger DiseaseDocument5 pagesClinical and Social Consequences of Buerger DiseaseRhenofkunairNo ratings yet

- Baseline Staging Tests in Primary Breast Cancer A Practice GuidelineDocument6 pagesBaseline Staging Tests in Primary Breast Cancer A Practice GuidelineRhenofkunairNo ratings yet

- Stab Wound Case ReportDocument3 pagesStab Wound Case ReportViesna Beby AulianaNo ratings yet

- Association of HLA-A9 and HLA-B5 With Buerger's DiseaseDocument2 pagesAssociation of HLA-A9 and HLA-B5 With Buerger's DiseaseRhenofkunairNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Paradigm Shift Essay 2Document17 pagesParadigm Shift Essay 2api-607732716No ratings yet

- Calibration Motion Control System-Part2 PDFDocument6 pagesCalibration Motion Control System-Part2 PDFnurhazwaniNo ratings yet

- The Teacher and The Community School Culture and Organizational LeadershipDocument10 pagesThe Teacher and The Community School Culture and Organizational LeadershipChefandrew FranciaNo ratings yet

- Binomial ExpansionDocument13 pagesBinomial Expansion3616609404eNo ratings yet

- Machine Learning: Bilal KhanDocument26 pagesMachine Learning: Bilal KhanBilal KhanNo ratings yet

- JD - Software Developer - Thesqua - Re GroupDocument2 pagesJD - Software Developer - Thesqua - Re GroupPrateek GahlanNo ratings yet

- Empowerment Technology Reviewer: First SemesterDocument5 pagesEmpowerment Technology Reviewer: First SemesterNinayD.MatubisNo ratings yet

- Vidura College Marketing AnalysisDocument24 pagesVidura College Marketing Analysiskingcoconut kingcoconutNo ratings yet

- ROPE TENSIONER Product-Catalog-2019Document178 pagesROPE TENSIONER Product-Catalog-2019jeedanNo ratings yet

- Statement of Compulsory Winding Up As On 30 SEPTEMBER, 2008Document4 pagesStatement of Compulsory Winding Up As On 30 SEPTEMBER, 2008abchavhan20No ratings yet

- Learning Stations Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesLearning Stations Lesson Planapi-310100553No ratings yet

- Reservoir Rock TypingDocument56 pagesReservoir Rock TypingAffan HasanNo ratings yet

- Colour Ring Labels for Wireless BTS IdentificationDocument3 pagesColour Ring Labels for Wireless BTS Identificationehab-engNo ratings yet

- THE PEOPLE OF FARSCAPEDocument29 pagesTHE PEOPLE OF FARSCAPEedemaitreNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Core Concepts of Accounting Information Systems 14th by SimkinDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Core Concepts of Accounting Information Systems 14th by Simkinpufffalcated25x9ld100% (46)

- AE-Electrical LMRC PDFDocument26 pagesAE-Electrical LMRC PDFDeepak GautamNo ratings yet

- Vehicle Registration Renewal Form DetailsDocument1 pageVehicle Registration Renewal Form Detailsabe lincolnNo ratings yet

- 2016 Mustang WiringDocument9 pages2016 Mustang WiringRuben TeixeiraNo ratings yet

- EE290 Practice 3Document4 pagesEE290 Practice 3olgaNo ratings yet

- HistoryDocument144 pagesHistoryranju.lakkidiNo ratings yet

- Variable Speed Pump Efficiency Calculation For Fluid Flow Systems With and Without Static HeadDocument10 pagesVariable Speed Pump Efficiency Calculation For Fluid Flow Systems With and Without Static HeadVũ Tuệ MinhNo ratings yet

- Master of Commerce: 1 YearDocument8 pagesMaster of Commerce: 1 YearAston Rahul PintoNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 Family PlanningDocument84 pagesLecture 1 Family PlanningAlfie Adam Ramillano100% (4)

- Florence Walking Tour MapDocument14 pagesFlorence Walking Tour MapNguyễn Tấn QuangNo ratings yet

- Positioning for competitive advantageDocument9 pagesPositioning for competitive advantageOnos Bunny BenjaminNo ratings yet

- Micropolar Fluid Flow Near The Stagnation On A Vertical Plate With Prescribed Wall Heat Flux in Presence of Magnetic FieldDocument8 pagesMicropolar Fluid Flow Near The Stagnation On A Vertical Plate With Prescribed Wall Heat Flux in Presence of Magnetic FieldIJBSS,ISSN:2319-2968No ratings yet

- Unit 1 - International Banking Meaning: Banking Transactions Crossing National Boundaries Are CalledDocument6 pagesUnit 1 - International Banking Meaning: Banking Transactions Crossing National Boundaries Are CalledGanesh medisettiNo ratings yet

- PWC Global Project Management Report SmallDocument40 pagesPWC Global Project Management Report SmallDaniel MoraNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court rules stabilization fees not trust fundsDocument8 pagesSupreme Court rules stabilization fees not trust fundsNadzlah BandilaNo ratings yet

- Amar Sonar BanglaDocument4 pagesAmar Sonar BanglaAliNo ratings yet