Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Laying Claim To Beirut - Urban Naratives and Spatial Identity in The Age of Solidere

Uploaded by

Aida BiscevicOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Laying Claim To Beirut - Urban Naratives and Spatial Identity in The Age of Solidere

Uploaded by

Aida BiscevicCopyright:

Available Formats

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Critical Inquiry.

http://www.jstor.org

Laying Claim to Beirut: Urban Narrative and Spatial Identity in the Age of Solidere

Author(s): Saree Makdisi

Source: Critical Inquiry, Vol. 23, No. 3, Front Lines/Border Posts (Spring, 1997), pp. 660-705

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1344040

Accessed: 23-08-2014 12:28 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Laying Clainl to Beirut: Urban Narrative and

Spatial Identity in the Age of Solidere

Saree Makdisi

As regards coastal towns, one must see to it that they are situated on

a height or amidst a people sufficiently numerous to come to the

support of the town when an enemy attacks it. The reason for this is

that a town which is near the sea but does not have within its area

tribes who share its group feeling, or is not situated in rugged moun-

tain territory, is in danger of being attacked at night by surprise. Its

enemies can easily attack it with a fleet. They can be sure that the

city has no one to call to its support and that the urban population,

accustomed to tranquility does not know how to fight.

IBN KHALDUN, The Muqaddamclh

When he came to the end of his journey, Abd al-Karim didnt realize

hed traveled more than all the shoe shiners in the world. Not be-

cause he had come all the way from Mashta Hasan in Akkar to Bei-

rut, but because Beirut itself travels. You stay where you are and

All translations are my own unless otherwise noted.

An earlier and much shorter version of this essay was presented at the Middle East

Studies Association (MESA) conference in Phoenix, November 1994; part of section 3 was

presented at the MESA conference in Washington, D.C., December 1995; part of section 4

was presented at the "Dislocating States" conference on globalization held at the University

of Chicago in 1996. Portions of this essay previously appeared in Saree Makdisi, "Letter

from Beirut," ANY(Architecture New York) 5 (Mar.-Apr. 1994): 56-59.

For the formation and elaboration of many of the ideas I present here, I am deeply

indebted to discussions with my parents and brothers, Ronald Abdelmoutaleb Judy, Rich-

ard Dienst, Cesare Casarino, Paul Silverstein, David Rinck, Nadya Engler, Roger Rouse,

Maha Yahya, Michael Speaks, Homi Bhabha and the other coeditors of Crttical Inquiry, Elias

CrS2cal Inquiry 23 (Spring 1997)

X) 1997 by The University of Chicago. 0093-1896/97/2303-0007$01.00. All rights reserved.

661

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

s

. : . .

;-s ,2<-tv-;; #,r'-_,---S- X <>S *;/_- ; '> s } --, - ^ ;

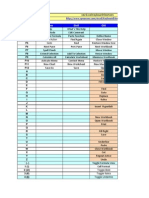

FIC. l(a). What used to be Martyrs' Square, facing south; the statue has been re-

moved for renovation. The excavation in the foreground is an archaeological dig. The re-

maining buildings in the backround mark Solidere's southern perimeter. Photo by author.

FIG. l(b). Postcard of Martyrs' Square before the war, facing north. The street lamp

in the foreground (near the buses) is visible in its postwar ruination in the photo in fig. 5.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

662 Saree Makdisi Laying Claim to Beirut

it travels. Instead of you traveling, the city travels. Look at Beirut,

transforming from the Switzerland of the East to Hong Kong, to Sai-

gon, to Calcutta, to Sri Lanka. It's as if we circled the world in ten or

twenty years. We stayed where we were and the world circled around

us. Everything around us changed, and we have changed.

ELIAS KHOURY, The Journey of Little Gandhi

The very center of Beirut is today a wasteland. For thousands of square

meters extending from Martyrs' Square little remains of the heart of this

ancient city. Several adjoining areas are made up of a patchwork of build-

ings slated for recuperation and of naked sites where buildings or souks

long since bulldozed or demolished once stood. Today a bold new

rebuilding project is underway, one that, under the aegis of a single

company (Solidere), promises to bring new life to the center of the city;

indeed, the company's slogan is Beirut An Ancient City for the

Future. Ironically, though, in the months since reconstruction officially

began in earnest (summer 1994), more buildings have been demolished

than in almost twenty years of artillery bombardment and house-to-

house combat.

As of the summer of 1994, indeed, whatever one wants to say about

the reconstruction plan currently being put into effect in central Beirut

is almost (but not quite) beside the point. For the object of discussion

the center of the city virtually does not exist any longer; there is, in its

place, a dusty sprawl of gaping lots, excavations, exposed infrastructure,

and archeological digs. Critics of the reconstruction plan mourn the loss

of the old city center; but its supporters claim that the old city center had

been left beyond salvation by the end of the war and that not only was

reconstruction on this scale inevitable but, for any number of reasons,

this particular reconstruction plan was and is the only possible option.

The debate has centered for the most part on how or why or whether the

current plan is the only option. In the meantime, we are losing sight of

Khoury, Ramiz Malouf (director of information at Solidere), Zakaria Khalil (of the Town

Planning Deparment at Solidere), Najah Wakeem, and above all Kamal Hamdan. This essay

forms only one part of a much larger project; in subsequent essays I more fully elaborate

the historical questions raised by the Solidere project, and I also try to move beyond critique

to an elaboration of alternatives to the Solidere project. What is at stake in the present essay

is merely an outline of the project and an overall assessment of some of its political and

cultural ramifications.

Saree Makdisi is an assistant professor of English and comparative

literature at the University of Chicago. He is the author of Universal Em-

pire: Romanticism and the Culture of Modernization (forthcoming). He has also

been writing a series of essays, including this one, on the politics of cul-

ture in the contemporary Arab world.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FIG. 2. The wasteland of what used to be Martyrs' Square, with one of the ubiquitous

Mercedes dumptrucks in foreground and a "recuperated" building in background. Photo

by author.

FIG. 3. Infrastructure installation. The scale of some of the work on the infrastruc-

ture can be quite overwhelming, evocative perhaps of a technological sublime. Photo by

author.

l s a

s w s

.e ss.. .. Z "w * w t < h*wo *

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

664 Saree Makdisi Laying Claim to Beirut

how it came to be the only option, how other options were foreclosed

long before the reconstruction effort officially began, how the whole pro-

cess has been presented to Lebanon and the world by Solidere and others

as an accomplished fact. Now the city center appears as a blank slate, as

an "inevitable" problem with an '4inevitable" solution, and the ''solutiorl''

itself appears as the fulfillment of its own self-fulfilling prophecy.

Blank or not, the city center is a surface that will be inscribed in the

coming years in ways that will help to determine the unfolding narrative

of Lebanon's national identity, which is now even more open to question.

For it is in this highly contested space that various competing visions of

that identity, as well as of Lebanon's relationship to the region and to the

rest of the Arab world, will be fought out. The battles this time will take

the form of narratives written in space and time on the presently cleared-

out blankness of the center of Beirut; indeed, they will determine the

extent to which this space can be regarded as a blankness or, instead, as

a haunted space: a place of memories, ghosts.

I should add at once that the relationship between these spatial nar-

ratives and Lebanon's national identity can never be reduced to a simple

equivalence and that whatever vision ultimately takes shape in central

Beirut will not finally hold all the answers to the questions surrounding

this identity. Indeed, one cannot overemphasize the extent to which this

identity, and even the very existence of an entity called Lebanon to which

it supposedly corresponds, has been disputed. Lebanon's narrative of self-

understanding began with formative sectarian struggles in the 1860s

(whose subsequent significance for Lebanon's national identity was deter-

mined largely under the aegis of the various European empires as well as

the Ottoman Empire)l and culminated in the horrors of the 1975-1990

war, which left around 150,000 dead and 300,000 wounded. The war was

in a sense fought over different constructions of the nation. For although

all nations and all nationalisms are artificial constructions, not all nations

have faced the same difficulties of trying to invent a community as has

Lebanon. Nor have many nations paid the terrible price that Lebanon

has paid for not having successfully come to terms with itself as such an

artificial entity (not that such a project of self-understanding needs to be

understood in strictly nationalist terms, nor in terms that isolate Lebanon

from the rest of the Arab world).2

1. See Ussama Makdisi, "The Modernity of Sectarianism in Lebanon," Middle East

Report 26 (Summer 1996): 23-26, 30.

2. Indeed, the question of Lebanese national identity is inseparable from the broader

question of national and communal identity in the rest of the Arab world. In another essay,

I discuss the failure of the project of nationalism in the Arab world and the relevance of the

questions of Palestine and of Lebanon for contemporary Arab reevaluations of nationalism

and national economic development. See Saree Makdisi, "'Post-Colonial' Literature in a

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Neocolonial World: Modern Arabic Culture and the End of Modernity," Boundary 2 22

(Spring 1995): 85-1 15.

Critical Inquiry

Spring 1997 665

iN;i -sBt

FIC. 4. Wartime damage to the city center. Photo by author.

During the war, territories proliferated, defined according to subna-

tional community or sectarian identities. Other spaces were abandoned,

most dramatically the so-called Green Line dividing east and west Beirut,

I. Wz N

N ! [ i q

Wi

S1tg

Xters

...... ... ..... .. w . . ... ....

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

666 Saree Makdasi Laying Claim to Beirut

and above all the very heavily damaged city center, which for more than

fifteen years remained an emptied-out site marking the graveyard of na-

tional dialogue and reconciliation.3 To be sure, the questions generated

by the war will continue to be contested at various levels and through

different modalities (in a reversal of the terms of von Clausewitz's famous

dictum). However, central Beirut must, I believe, be seen as a key site for

the development and contestation of these and other questions; and it is

for this reason that the process of reconstruction assumes a significance

that far exceeds the directly material terms in which it has already begun

to take shape. This shape takes the form of the work now being under-

taken by the newly invented joint-stock Lebanese Company for the Devel-

opment and Reconstruction of Beirut Central District, better known by

its French acronym Solidere, which now has legal or managerial control

over the land in the center of the city. But here it becomes necessary to

explain what Solidere's proposed spatial narrative looks like and what are

its origins and the origins of the company itself.

1. Berytus Delenda Est; or, 'Xn Ancient City for the Future"

Following the close of the traumatic events of 1975-76 (which

marked the beginning of the Lebanese war), the question of what to do

about the damage to the central district of Beirut was first opened for

discussion. The war seemed then to be over, and various public and pri-

vate organizations began to consider proposals for the reconstruction ef-

fort. These discussions culminated in the first official plan, in 1977,

commissioned by the Council for Development and Reconstruction

3. See Kamal Salibi, A House of Many Mansions: The Hzstory of Lebanon Reconsidered

(Berkeley, 1988). "In all but name," Salibi wrote during the war, "Lebanon today is a non-

country. Yet, paradoxically, there has not been a time when the Muslims and Christians of

Lebanon have exhibited, on the whole, a keener consciousness of common identity, albeit

with somewhat different nuances." Thus, he goes on to say,

The people of Lebanon remain as divided as ever; the differences among them have

come to be reflected geographically by the effective cantonization of their country,

and by massive population movements between the Christian and Muslim areas

which have hardened the lines of division. In the continuing national struggle, how-

ever, the central issue is no longer the question of the Lebanese national allegiance,

but the terms of the political settlement which all sides to the conflict, certainly at the

popular level, generally desire. Disgraced and abandoned by the world, it is possible

that the Lebanese are finally beginning to discover themselves. [Pp. 2-3]

Now that the war has indeed ended, it has been argued that central Beirut should

serve as a site in which the spatialized sectarianism of the war could be deconstructed and

hence as a site in which a new sense of national identity could be given spatial expression,

by, among other things, bringing together members of the different sects in a common and

collectively reinvented area.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Critical Inquiry

Spring 1997 667

(CDR), to rebuild the city center along the lines of its traditional layout, to

restore its centrality in the life of Beirut, and to improve its infrastructure.

Particular emphasis was placed, however, on the need to reintegrate the

center in both class and sectarian terms (that is, to restore the class and

communal diversity that had characterized it before the war) and on the

need to ensure the reintegration of the center into the rest of the city's

urban fabric. Before the war, the downtown had served not only as a

commercial and cultural center but also as a transport hub (all bus and

service-taxi routes originated and terminated there, for instance, so that

trips to different parts of the city or the country more often than not were

routed through the city center). As Jad Tabet points out, the 1977 plan

highlighted a desire "to remold the center of the Lebanese capital into a

meeting place for the various communities," while at the same time bear-

ing in mind the need to "modernize the center in an attempt to solve the

serious problems of functioning and access Beirut faced before the war,

while maintaining the specific image of its site, history, and Mediterra-

nean and 'oriental' character."4

In any case, the war was not yet over. In late 1977, fighting resumed,

punctuated by the first Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1978 and the sec-

ond Israeli invasion in 1982, which culminated in the siege (and tempo-

rary Israeli occupation) of west Beirut in the summer of that year. After

the massacre of Palestinian refugees at the Sabra and Shatila refugee

camps, multinational "peacekeeping" forces returned to Beirut in Sep-

tember 1982, and the Israelis were compelled to withdraw from Beirut

and to retreat to a heavily defended occupied strip of southern Lebanon.

Once again the war seemed to be over.

In 1983, OGER Liban, a private engineering firm owned by the Leb-

anese billionaire Rafiq Hariri, took over the reconstruction project and

commissioned a master plan from the Arab consultancy group Dar al-

Handasah. In late 1983, and in the absence of a new of Scial plan, demoli-

tion began in the central area on the pretext of cleaning up some of the

damage. This "cleaning up," whose perpetrators remain officially uniden-

tified (though it has been repeatedly alleged that they stand behind to-

day's reconstruction project),5 involved the destruction of some of the

district's most significant surviving buildings and structures, as well as

Souk Al-Nouriyeh and Souk Sursuq and large sections of Saifi without

recourse to official institutions, on what critics argue were false pretenses,

4. Jad Tabet, "Towards a Master Plan for Post-War Lebanon," in Recovering Beirut:

Urban Design and Post-War Reconstruction, ed. Samir Khalaf and Philip S. Khoury (Leiden,

1993), p. 91.

5. See, for example, Nabil Beyhum et al., I'amar Beirut wa'l fursa al-da'i'a [The Recon-

struction of Beirut and the Lost Opportunity] (Beirut, 1992), p. 16. See also Assem Salaam,

"Le Nouveau plan directeur du centre-ville de Beyrouth," in Beyrouth: Construire l'avenir,

reconstruire le passe 2 ed. Beyhum, Salaam, and Tabet (Beirut, 1996).

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

668 Saree Makdisi Laying Claim to Beirut

and in total disregard for the then-existing (1977) plan for reconstruc-

tion, which had specifically called for the rehabilitation of those areas of

the city center.6

In 1984, however, another round of fighting forced the cessation of

planning and reconstruction activities, and intensive shelling caused fur-

ther damage to the downtown area. When the war entered another lull

in 1986, further unofficial demolition was carried out in the downtown

area; the same parties that had been behind the 1983 demolitions alleg-

edly began implementing a plan (bearing some distant resemblance to

the current Solidere proposals) that called for the destruction of a large

proportion up to 80 percent of the remaining structures of the city

center. According to critics, this was carried out without the authorization

or approval or interference of any official or governmental insti-

tution.7

Following the final paroxysm of violence that signalled at last the end

of the war in 1990, attention once again focused on the reconstruction of

the now very heavily damaged center of Beirut. And it was in this context

that several developments took place that enabled the resumption of the

6. See Beyhum et al., I'amar Beir7lt wa'lfursa al-da'i'a, pp. 15-25, esp. pp. 15-21.

7. See ibid., p. 16.

FIG. 5.- Martyrs' Square after the war but before the Solidere demolitions, facing

south; compare with fig. l(a), which was taken from the same standpoint, to see the scale

of the demolitions. All the buildings in the photo have been removed. Photo by author.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FIG. 6. Aerial photograph of central Beirut following the war. Solidere's perimeter,

marked by the large boulevards, is clearly visible. Note the Normandie landfill at the north-

ern end of the photo; Place de l'Etoile and Martyrs' Square are clearly visible in the center.

Source: Solidere.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

670 Saree Makdisi Laying Claim to Beirut

kind of planning that had first begun with the unofficial demolitions of

1983-86 and that ultimately led to the formation of Solidere. First of all,

Fadel el-Shalaq, the head of Hariri's OGER Liban, was appointed as the

head of CDR. As Hashim Sarkis points out, "in effect what this has meant

is that the main private organization in the building industry has taken

over the ofiicial planning advisory body. The agency that the government

used to control private development has now reversed its role."8 Indeed,

this development marked only the beginning of the state's abdication of

its authority and any direct role it might have played in the reconstruc-

tion of central Beirut, and the beginning of a political-economic discourse

we might identify as Harirism, which would culminate in 1992 when

Rafiq Hariri himself became prime minister of Lebanon. It is worth

pointing out that Hariri has always regarded the reconstruction of central

Beirut as the crowning project of the economic "rebirth" that he claims

to represent.

Also in 1991, a new set of master plans for the reconstruction of

central Beirut was released by Dar al-Handasah (the consultancy firm

that had been first commissioned by OGER Liban in 1983). These plans,

which had been drawn up by the Dar al-Handasah architect Henri Edde,

called for what has been fairly unanimously denounced as an outrageous

rebuilding project to follow the virtually total demolition of whatever

structures remained in the city center. Edde's plan included such features

as the creation of an artificial island to house a "world trade center" and

an eighty-meter-wide boulevard rivalling the Champs-Elysees (which is a

mere sixty meters wide!), as well as a street layout, including overpasses,

bearing no resemblance to either what had been there before or to the

urban grain of the rest of Beirut. This plan, as Tabet argues, would have

made the city center an isolated "island of modernity,"9 all but cut oS

from the rest of the city. In the face of a huge public outcry, the CDR and

Dar al-Handasah were forced to scrap the scheme, and they set to work

on a new master plan.

The last key event of 1991 had to do with the question of property

rights in central Beirut. Given the destruction in the city center, but also

the increased fragmentation of property rights, the diffusion of property-

rights claimants and related inheritance disputes, the idea was put for-

ward to have a single private real estate firm expropriate all the land in

the city center and take over the rebuilding process.l Since the main

governmental body in charge of reconstruction (the CDR) had already

8. Hashim Sarkis, "Territorial Claims: Architecture and Post-War Attitudes Toward

the Built Environment," in Recovering Beirut, p. 114.

9. Tabet, "Towards a Master Plan for Post-War Lebanon," p. 95. See also Beyhum,

"Beyrouth au coeur des debats," Les Cahiers de l'Orient 32-33 (1994): 103.

10. Some estimates suggested that there were as many as 250,000 property-rights

claimants in the central district, since Lebanese law protects claims not only by property

owners and their descendants but by lessors and their descendants as well.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FIG. 7. Martyrs' Square, facing north toward the sea. All the buildings have been

removed to make way for a boulevard linking Fouad Chehab Avenue to the port. Photo

by author.

FIG. 8. Martyrs' Square, facing north. Note the poster in the background, presenting

what this scene is supposed to look like after the reconstruction. Photo by author.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

672 Saree Makdisi Laying Claim to Beirut

been placed under the leadership of those leaning toward the creation of

such a firm, this body (in cooperation with properly private-sector inter-

ests, notably Hariri and OGER Liban, that were also in support of the

single firm concept) commissioned another study from Dar al-Handasah,

which, unsurprisingly, called for the creation of a single firm to take over

the center of Beirut. The new plan also called for the demolition of most

of the remaining structures in the center in order to facilitate an unfet-

tered large-scale development project. But despite the growing support

for this new plan in certain public- and private-sector circles, opposition

to it also grew from both the general public and a protest group that was

formed to debate the idea and to try to generate possible alternatives to it.

Even as the plan was being widely debated, however, official sanction

for it was being consolidated, most importantly in the form of laws and

decrees calling for the institution of a single company to take over the

real-estate rights in central Beirut. The most important of these is Law

117 of 7 December 1991, which provided the legal framework for the

constitution of such a company, a law that has been repeatedly de-

nounced as unconstitutional." It should be noted, however, that this law

in no way mandated the creation of Solidere specifically or as such

that is, the collection of private interests and powerful individuals who

gathered together as Solidere's board of founders in 1992. Thus without

regard to the public or even to those whose property would be expro-

priated by the company did Solidere come into being: the ultimate ex-

pression of the dissolution of any real distinction between public and

private interests or, more accurately, the decisive colonization of the for-

mer by the latter. As the Lebanese architect and public planner Assem

Salaam argues, "entrusting Beirut's Central Business District (CBD) rede-

velopment to the CDR is a typical example of the dangers inherent in the

state's abdication of its role in orienting and controlling one of the most

sensitive reconstruction development projects in the country."'2

In the spring of 1992, further demolition was begun in the down-

town area, this time on behalf of the government, even though the recon-

struction plan as such had not yet been approved or even defined. Not only

were buildings that could have been repaired brought down with high-

explosive demolition charges, but the explosives used in each instance

were far in excess of what was needed for the job, thereby causing enough

damage to neighboring structures to require their demolition as well.'3

Thus, for each building "legitimately" demolished several other buildings

were damaged beyond repair, declared hazards, and then demolished

11. See "Al-sharika al-iqariyya fi al-itarayn al-dustouri wa al-qanouni" [The Legal and

the Constitutional Aspects of the Real Estate Company], in I'amar Beirut wa'lfursa al-da'i'a,

pp. 87-88.

12. Salaam, "Lebanon's Experience with Urban Planning: Problems and Prospects,"

in Recovering Beirut, p. 198.

1 3. See Beyhum et al., I'amar Beirut wa'lfursa al-da'i'a, pp. 15-20.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FIG. 9. A map of the proposed 1991 reconstruction plan. Source: Beyhum et al.,

Reconstruction of Beirut anJl the Lost Opportunity ( 1992).

* .4-. wXv s jEmat v a * \ f iS

FIG. 10. An artist's impression of the proposed 1991 plan. Source: Beyhum et al.,

Reconstruction of Beirut and the Lost Opportunity ( 1992).

::

* e

> . . .

* t s- P -swe ...,i

s s 1vE1 tX -; ,rs F - + .,:t:g-''j

v44a

<1gw

Asi*s

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

674 Saree Makdisi Laying Claim to Beir7lt

themselves with the same zeal for big explosions. It is estimated that, as

a result of such demolition, by the time reconstruction efforts began in

earnest following the formal release of the new Dar al-Handasah plan in

1993, approximately 80 percent of the structures in the downtown area

had been damaged beyond repair, whereas only around a third had been

reduced to such circumstances as a result of damage inflicted during the

war itself.l4 In other words, more irreparable damage has been done to the center

of Beirut by those who claim to he interested in salvag?ng and rebuilding it than had

been done during the course of the preceding fifteen years of shelling and house-to-

house combat. 15

As this demolition was being carried out, though, opposition grew.

In the spring of 1992, for instance, a group of concerned architects was

formed to formulate alternatives to the (still unofficial) reconstruction

plan. In May of that year, this group organized a conference to debate

issues of aesthetic, cultural, social, economic, and political significance

in any reconstruction effort, and to call a halt to the demolition.l6 The

conference also called for the necessity of public and governmental de-

bate before any decisions could be made and urged that appropriate con-

sideration be given to their proposals and to other issues of concern

raised in the large-scale public discussions by the holders of property

rights in the downtown area.

In spite of all these calls, however, and in spite of the increasing at-

tention and coverage being given to the national parliamentary elections

that year (electoral campaigning, begun in earnest in the summer of

1992, overshadowed the debates over downtown Beirut), the government

passed a series of laws enabling the creation of Solidere, whose articles of

incorporation were approved in July of that year. One of the last acts of

the previous government (shortly after the elections and before it re-

signed and was replaced by the Hariri cabinet), in fact, was the formal

approval of Dar al-Handasah's brand new master plan on 14 October

1992. Thus in an atmosphere of national anxiety and concern with the

outcome of the September elections, and with no public participation in

decision making the future of the heart of Beirut was decided, long

before any (official) investments had been made in it. Demolition was

14.Seeibid.,p.l9.

15. Salaam, for one, points out that more buildings were destroyed by bulldozers than

by the war. According to Salaam, "I1 y a eu plus d'immeubles detruits par les bulldozers que

par la guerre. En 1992, des constructions bordaient encore la place des Martyrs. Elles ont

ete demolies en six mois" (Le Monde, 3 June 1995). Some cynics, in fact, assert that much of

the fighting in the downtown area during the war was paid for in order to achieve as much

destruction as possible; Najah Wakeem has made this allegation publicly on several occa-

sions. Such views are certainly cynical, but given the many twists and turns of the war, they

cannot be entirely ruled out of the question; in any case, many seemingly equally improba-

ble events have been substantially documented.

16. The papers from this conference are collected in Beyrouth.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Critical Inquiry Spring 1997 675

resumed in 1994 and, by the end of that year, as I've said, much of the

center of the city had been razed.

Solidere itself makes little reference to its prehistory or to previous

plans for reconstruction in the center of Beirut. Formally established on

5 May 1994, the company says in its information booklets that it repre-

sents the largest urban redevelopment project of the l990s. Its sole refer-

ence to the recent history of the city center is as follows:

Located at the historical and geographical core of the city, the vibrant

financial, commercial and administrative hub of the country, the Bei-

rut Central District came under fire from all sides throughout most

of the sixteen years of fighting. At the end of the war, that area of the

city was afflicted with overwhelming destruction, total devastation

of the infrastructure, the presence of squatters in several areas, and

extreme fragmentation and entanglement of property rights involv-

ing owners, tenants and lease-holders. 17

Solidere thus presents itself as a healing agency, designed to help central

Beirut recover from its "afflictions." It makes no mention of the previous

history of reconstruction not only because these histories do not exist in

official terms but also because of the company's peculiar and contradic-

tory relationship to history (to which I shall return shortly).

Solidere's capital consists of two types of shares, together initially val-

ued at U.S.$1.82 billion. Type A shares, initially valued at U.S.$1.17

billion, were issued to the holders of expropriated property in the down-

town area, in "proportion" to the relative value of their property claims,

as adjudicated by the company's board of founders. A further issue of 6.5

million type B shares was released to investors, bringing in new capital at

an initial stock offer of U.S.$ 100 per share (and indeed the stock offering

was denominated in U.S. dollars, not Lebanese pounds). Within a few

weeks, until its closing in January 1994, the stock offering had been over-

subscribed by 142 percent (that is, U.S.$926 million, offered by some

twenty thousand subscribers). There is, however, an important caveat to

all this. Stocks may only be purchased or held by certain individuals in

the following order of priority: the original holders of property rights

(of all nationalities, though presumably the majority would have been

Lebanese); Lebanese citizens and companies; the Lebanese state and

public institutions; and persons of Lebanese origin, as well as the citizens

and companies of other Arab countries. Non-Arabs, unless they were

originally property holders, are thus not permitted to buy shares

(though, because of special exemptions to strict Lebanese laws regulating

the ownership of land by foreigners, they will be allowed to purchase real

estate from the company once land and buildings are placed on the mar-

17. Solidere, Information Booklet 1995, p. 5; hereafter abbreviated IB.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

676 Saree Makdisi Laying Claim to Beirut

ket by Solidere). Furthermore, there is a maximum individual sharehold-

ing limit of 10 percent.

Solidere shares are now being exchanged on the company's own pri-

vate stock exchange (not on the official Beirut Stock Exchange, which the

company has circumvented). As of December 1994, shares had already

appreciated in value by some 50 percent, though they have come down

considerably since then.l8 In addition to the expected returns and divi-

dends (which should accelerate as buildings and land are put on the mar-

ket), which the board of founders estimated at approximately 18 percent

over a twenty-five year period, the company and its investors will not be

taxed, either on income from the project or on capital gains, for the first

ten years. In fact the first sales of land are already in process, reportedly

at a price of U.S.$950 per built-up square meter (considering that the

project entails a built-up area of some 4.5 million square meters, one can

get from this some sense of the value of Solidere's property).l9

Solidere's massive advertising campaign not only plastered huge

posters all over Beirut and the rest of Lebanon but also took out ads in

foreign newspapers and magazines. "In Lebanon," reads one of Solidere's

ads in the Financial Times, "everyone knows we must rebuild Beirut's city

centre. We know how."20 Another ad, in the New York Times, proudly pro-

claims, "We've invested in the future of an ancient city.''2l Large-scale

mailings of glossy information booklets, maps, and even a miniature set

of pictures taken from oversized posters have spread throughout Leba-

non ("Le centre ville vous invite...."). All of this, incidentally, appeared

before the company itself had actually come into being (the ads were tech-

nically sponsored by Solidere's "board of founders").

In any case, what few people in Lebanon seem to realize is that Soli-

dere is not going to rebuild the downtown area: it is going to oversee

the rebuilding of the downtown area. Other than the infrastructure, the

company will limit itself to at most about a third of the construction of

actual buildings. To be more specific, Solidere will, according to its infor-

mation booklets, have four principal functions: first, to supervise the exe-

cution of the government-authorized reconstruction plan; second, to

finance and rebuild the infrastructure; third, to rehabilitate certain build-

ings and structures and the development of the rest of the real estate;

and, fourth, to manage and sell these properties, buildings, and other

facilities. One of the striking features of the development of the infra-

structure is that not only will the Lebanese state deny itself any possible

tax revenues from this development for the first ten years but it will even

18. As of February 1997, shares are traded at around U.S.$110.

19. See al-Hayat, 4 July 1995.

20. Financial Times, 9July 1993, p. 14.

21. New York Times, 22 Nov. 1993, p. C11.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

pTg f

/

l f H; .

! _

* a,,

;i'

^ A u . ... _< -4D * .......................................... . s ; ............................ :

;,^ tt +tr,kB

. 7@ #;txr". 1"''t'!" fli' >!t

<,

" '"." i--

.. .. . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . * . .................. . .. .. .: .... : t ; e;. 8 . 4 U s .. , , R . . . . ............. .. - ... A . . , . .............................. 4 El e i ,o>.ctSN8<et;

FIGS.

11-12.

Artists'

impressions

of the new Solidere

plan.

Source:

Solidere.

*e

s

- v ^ . . ....

l |

- m

-- . 4

! . .

. ...... .............. _._

_::. '.:._.

,

l

3 ..... a i .. > > 4, .,. , :: . _

-_2xd we l : t : a

'..

W S CYP:l

_b.,=..._

X

1

S. : .: :

..

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

678 Saree Makdisi Laying Claim to Beirut

go so far as to actually pay for the infrastructure repairs (estimated by

the company at U.S.$565 million in 1993 dollars), largely by allocating

the company extra space for development in an area of land to be re-

claimed from the sea.22

Solidere's rebuilding project encompasses a surface area of about 1.8

million square meters, which will include the reclamation of over 600,000

square meters from the sea. The plan will involve the development of

over 4.5 million square meters of built-up space, of which around half

will be dedicated to residential units. Approximately half of the area will

be owned, managed, and ultimately sold by Solidere. Much of the rest of

it will be ceded to the state (infrastructure, parks, open spaces), and an

additional 80,000 square meters are exempted lots (government and reli-

gious buildings, which revert to their previous owners, that is, the state

and the various religious communities). Some 260 buildings in the center

have been designated as recoverable and hence spared the bulldozer and

dynamite crews; their former owners or other interested parties may re-

develop and refurbish them. Anyone, including former owners (who are

given priority), wishing to recuperate such a building, however, would

have to pay to the company a 12 percent surcharge on the estimated value

of the lot; they must also be prepared to repair the building within a two-

year time frame and subject their plans to an architectural brief issued

by Solidere and under the company's strict supervision. Solidere's recu-

peration briefs are intended to preserve each recuperated building's orig-

inal external features and faSades so that the central district retains its

previous (surface) appearance to the greatest extent possible and so that

the central district can be woven (visually) into the rest of the urban fabric

of Beirut.

22. According to IB, "the Company shall be reimbursed by the State for all infrastruc-

ture costs incurred, in one or a combination of the following ways: in cash, in State-owned

land within the BCD [Beirut Central District], in land within the reclaimed land zone, or

in concessions for the exploitation of infrastructure services." Since the state is going to end

up paying for the project in the end, many critics of the Solidere plan argue that, at the

very least and if for no other reason than this-the state should have much more of a

direct role in the company's affairs and even that the state should simply seek financing

from multilateral lending agencies or from banks and manage the reconstruction by itself,

reaping at least some of the benefits in the form of tax and other revenues, of which it is in

considerable need, rather than passing those on to a private company and ultimately paying

for the reconstruction in any case. It should be noted that critics of the Solidere plan have

argued that the real cost for the infrastructure in the center of the city is in the range of

U.S.$50-U.S.$70 million, a figure well within the reach of the Lebanese government; see,

for example, Le Monde, 3 June 1995. Since so much of the support for the single-firm

concept has been argued in terms of the government's supposed inability to pay for the

infrastructure and hence the need for private investment as opposed to public expendi-

ture-this is a crucial issue. Critics suggest that the government, now firmly in the hands

of certain private sector interests, has abandoned its own role in the city center in favor

of these same interests.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Critical Inquiry

Spring 1997 679

Solidere's master plan calls for the creation of a lively and attractive

urban core in Beirut, featuring a balanced mixture of office space, resi-

dential areas, commercial and retail zones, parks and tree-lined prome-

nades, as well as beach facilities and two yacht clubs. In contrast with the

notorious 1991 Dar al-Handasah plan (which in a way looks like a deliber-

ate red herring), a concerted effort has been made by Solidere's architects

and urban planners led by the Harvard-educated Oussama Kabbani-

not to depart visually from the traditional appearance or street plan of

the city center or adjoining neighborhoods (except in the area to be re-

claimed from the sea, which will be based on a grid layout with wider

streets). The company's advertising booklets rely heavily on visual and

photographic contrasts between the ruined central district as it stands

today, the bustle of the district in the heady prewar days of the 1960s and

1970s, and the promise of a poised and elegantly manicured downtown

sometime in the next ten or fifteen years.

In response to the various criticisms of the previous Dar al-Handasah

plan, the current master plan highlights the intended reintegration of

the central district within the greater Beirut metropolitan area. It will

also include the planned preservation of certain buildings in the historic

core (particularly in the relatively small area from the grand Serail to

Martyrs' Square); the "reconstruction" of some of the old souks; the

planned preservation of the lower-class and lower-middle-class residen-

tial areas within the central district (though it seems fairly obvious that

these areas will not take on their previous class identities and will proba-

bly be priced beyond the reach of most Lebanese citizens);23 and as a

nod toward the more culturally and environmentally motivated critics-

the planned creation of a seaside park (on the landfill), which will include

what one of the booklets refers to as "some cultural facilities," including

a library and a center for the arts. In addition, there is a policy that limits

high-rise buildings and calls for a seafront boulevard, hotels, restaurants,

cafes, gardens, and a new highway linking the central district with Beirut

International Airport, which is barely three miles away to the south.

A major feature of the Solidere plan allows for the preservation of

various archaeological finds, some of which will remain in their present

locations, others of which will be relocated to an archaeological park near

Martyrs' Square. The archaeological richness of the central district can-

not be overestimated: the earliest settlements in Beirut date to some

65,000 years ago, and the city has been inhabited and rebuilt by virtually

every major culture in the eastern Mediterranean. Present archaeological

23. Property prices in Beirut are today not only astronomical but out of all proportion

to the local economy; it is not unusual for a new apartment to be priced in the region of

one million dollars. It should be said that Solidere claims that its residential units will be

aimed at a variety of income groups, but it remains to be seen to what extent this claim will

be realized.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

X <

Q

i =

o Q

t cs .

ct o X

m: r

E r - o

Q < u:

: X X

h = t

= o

.-.: t

=D =

N = o

X < o-h

'v - <

X 55 m

55 = t

o < X

u: X t

= = o

; = Q

o .

wz *

Q bt

C3 o -

o = oD

X f^=

u Q Q

o

w r

o Q t

r bl

X Q:

; .n

bt X *-

o f =

o X -

| Q i

- Q =

V Q F

_ ,=

X, U

^ (,

. _

G C3

=

__ . , 1

.,,. . , . _

.@ v . D

: - X

Q

o

C;

. z N s

* D Q X

. O L) r

] s_ -

, _ , . _ . .

a _ . 9 C/D U

_ a > v t

z 0 O s

U < s

* E S

_

|' | Q

* , o) <

f . - - bt

_

.- X, :

-

_ Q

._

t

. , .

k __ ,,,,, S

tK+--iI . 6.

"i't'; 'l. ': .1z3;;7i 1 t

X ti }X.*l F--

m 4 - es t

,:^t.'...s, .g ,{..,..1t, .., 6 .._1i. }M

N Z > ' $' if .

S S,,

.S

! _,

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Critical Inquiry Sprang 1997 681

.

q 2; ' <3;l 'S j !r- ;Ut s

-

2E

FIG. 15. An artist's impression of the new Solidere plan. Source: Solidere.

digs in between work on the infrastructure, which is already under-

way organized by various Lebanese universities and financed by Soli-

dere and international agencies, have uncovered medieval and Ottoman

structures, and even earlier finds (Mamluke, Crusader, Arab, Byzantine,

Persian, Roman, Greek, Phoenician) and Canaanite, as well as Bronze

and Stone Age), including the recently uncovered walls of the Phoenician

city, which date from the second millennium B.C. One of the prizes that

archaeologists still hope to locate is the Roman law school, the first in the

Roman Empire and one of the most important until its destruction in

an earthquake. Originally somewhat equivocal about the archaeological

dimensions of the reconstruction project, Solidere now seems to be taking

it very seriously. According to the archaeologists I spoke to, some of the

major infrastructure work (including underground canals and part of the

road network) will be diverted or redesigned in order to work around

the recently uncovered ancient Phoenician city walls. The redeveloped

souk area (essentially a shopping mall) will be constructed along the axes

of the ancient city, which have remained largely the same since early Hel-

lenistic times. At the same time, of course, the company is turning the

architectural and archaeological preservation of certain sites to commer-

cial advantage; one Solidere strategist was quoted recently in Le Moruie,

saying, "we have been accused of the destruction of the architectural pat-

rimony of Beirut; that's false, and, more to the point, it's not in our inter-

$V E't::

xEE|a; {:f:N

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

682 Saree Makdisi Laying Claim to Beirut

--WS:: reX-isiEa-

FIC. 16. An archaeological site in the oldest part of the city. Note the ancient city

walls and the ruins of a Crusader castle. Photo by author.

est. Like the archaeology, it forms part of the marketing [program] of

Solidere."24

In visual terms at least (or at most), Kabbani's urban design team is

trying to ensure that the new city center will not look like a foreign body

in the heart of Beirut. However, the actual details of the actual construc-

tion of actual buildings remains, so far as one can tell, a mystery. We do

know that the appearance and faSades of recuperated buildings cannot

be altered in any way (though internally they can be entirely redesigned).

But other than that we know little or nothing. There was, for instance,

no outright winner in the 1994 International Ideas Competition for the

"reconstruction" of the souks. In reality, this subproject could only

amount to a construction from scratch, since the souks were razed, either

by Solidere itself or by its various predecessors (though it is worth asking

why this project relentlessly clings to the language of the re- rather than

admitting that it is not about the resurrection, redemption, recuperation,

reinvention, remembrance of that past but rather its invention from

scratch). An international jury of architects received 357 detailed propos-

als from 51 countries, of which 3 were named winners. In effect, however,

no one, or at least no one outside of Solidere, knows in any detailed way

what the future "souk" area will look like.

In any case, Solidere's concern for (indeed we might call it an obses-

sion with) appearances should not obscure the primary emphasis of the

24. Jean-Paul Lebas, quoted in Le Moruie, 3 June 1995.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Critical Inquiry Spring 1997 683

e

FIG. 17. Archaeological excavation of ancient Roman baths in the city center. Photo

by author.

project, which lies underneath and behind the various faSades and at

the level of infrastructure its greatest concern all along. In a sense, the

infrastructure project is at the heart of the matter here; it will be covered

up by faSades that may turn out to have a "Levantine" flavor but that

could just as easily have had no flavor at all (as with the original Dar

al-Handasah plan). Flavor in this context amounts to little more than a

marketing advantage, a way to sell the underlying infrastructure; the

company strategist quoted above goes on to say that the downtown's ar-

chaeological and architectural patrimony will form an essential element

in the competition between the rebuilt center of Beirut and other re-

gional centers, such as Dubai, that offer a similar technical infrastructure

but that lack Beirut's historical richness and hence the kind of flavor that

Solidere can lay claim to. "We will play this card," he promises.

The reclaimed land, for instance, will require an impressive infra-

structure to protect it from the sea, consisting of submerged caissons and

a lagoon formed by artificial breakwaters. The new road network will

be backed up by a series of tunnels and extensive underground parking

facilities (for 40,000 cars). The central district will have its own dedicated

underground power supply system. It will also have the most advanced

telecommunications infrastructure in the world. The telecommunications

services will allow for high-speed data communications, transactional da-

tabases, and of course international communications via satellite earth

stations and international submarine fiber-optic cable links. Beirut's basic

1.'''...1..1..1,o,1 1..,1, | | .l g

{: s r { . r r jeu B s ............................ ^ y

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Laying Claim to Beirut 684 Saree Makdisi

copper phone network will be backed up in the central district by digital

fiber-optic lines capable of carrying video signals as well as audio. Finally,

the district will be covered with GSM cellular service provided by no

fewer than ten base stations (GSM represents the leading edge of digital

mobile telecommunications).25 Finally, the central district, which is al-

ready close to the city's port, will be served by Beirut's newly expanded

international airport (which is being upgraded to serve 6 million passen-

gers annually) via the new expressway. And, for those who prefer the

luxury of travelling by yacht, two marinas will be directly incorporated

into the central district.

2. Beirut? Or, a City zuithout History?

Before resuming my reading of the overall Solidere scheme, I would

like to dwell for a moment on the "reconstruction" of the souk area and

on what it might tell us about Solidere's peculiar relationship to history.

The souk project forms part of the first phase of the overall reconstruc-

tion effort. Phase one is designed to set up two major magnets to draw

life back into the central district the banking area around Riad al-Solh

Square and Place de l'Etoile, and the souk area.

I have already mentioned that, even following the release of a sketch

of a master plan, it remains unclear what the new souk will look like. The

company's most recent (1995) information booklet says that the attempt

behind the "souk" project is to "recapture a lifestyle formerly identified

with the city center and re-create a marketplace where merchants pros-

per and all enjoy spending long hours" (IB, p. 25). Elsewhere in the book-

let, we are told that "the clearing of the old souks, which accompanied

the clearing and demolition of buildings and sites in the BCD mandated

by the Master Plan, paved the way for reconstruction of that district over

an area of 60,000 square meters." This district deliberately heavily dam-

aged, we will recall, in the demolitions of 1983 and 1986 and finally pul-

verized in the summer of 1994 will, as the booklet goes on to say,

"incorporate department stores, retail outlets, supermarkets, theaters, of-

fices, exhibition areas, residences and parking facilities. The total built-

up surface area will near 130,000 square meters" (IB, p. 17). Clearly, the

most pressing question here is not the one about how a collection of Pizza

25. With an expected 1 million electronic phone lines and 750,000 cellular lines, for

a population of 3.5 million, Lebanon should soon have the greatest number of phone lines

per capita of any country in the world; it is here, though, that this statistic, used internation-

ally as a benchmark of "development," reveals its shortcomings, since these extremely ex-

pensive services will be available only to a relatively small proportion of the Lebanese

population.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

; ; t00:, t' 9 -

8 ilili f!

:::LL::XiaSiSW-l

,,., ,, ;- . ,, . |! R -::{ :' Fl(;. 19.-Photograph of the excavations in the souk area; the huge hole has been dug to

'rX . / S J; l :, - ,, creat room fbr an underground garage. Note the scale of the excavation; the fence in the back-

.,' 0 0 --- tt 5, j--Aw s - H - -. ground is eight to ten feet high. The domed structure that has been spared is an early-sixteenth-

_ -- 1 '; } t; ! century Mamiuk sanctuary. Photo by author. , t ; ;; b - . -; , . | . W - X si->i ^ 1 7 8 t !}- - i- -- --. -;- Lt >''} rs

Fle;. 18.-A map of the proposed souk redevelop-

ment plan. Source: Solidere.

.. -- t ; l ; i .

-[<% 4\ffi0l

... : ':...!

. .. ,, . l

: .:,

,

.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

686 Saree Makdisi Laying Claim to Beirut

Huts, Safeways, Walgreens, McDonald's, Body Shops, Burger Kings, Be-

nettons, Gaps, Blockbuster Videos, and Tower Records gathered together

and given the benediction of the term souk will recapture any lifestyle

other than that of the postmodern shopping mall, which is clearly what

it would inevitably look like, largely because that's what it would be. In

fact, all we know is that, while calling itself a souk, this area can amount

to nothing more than a postmodern pastiche of the concept of the souk.

For how, in any case, could one re-create something like a souk, which is

not only the product of a long historical process but is also characterized

and even defined by spontaneity and above all heterogeneity? Indeed, to

speak of planning a souk is something of a contradiction in terms. Thus,

the souk subproject may be taken not merely as symptomatic of the larger

Solidere project but as a synecdoche for it.

Solidere's publications make use of the language of memory and af-

fect to characterize what they promise will be the flavor of the new central

district. But it seems clear that the simulacral effect of the reconstruction

project is to be achieved specifically and solely in visual terms or, to be

precise, in terms of appearance and faSade. Hence the souk area will be

called a souk because it will (supposedly) somehow look like what a souk

looks like. But what does a souk look like? In particular, what did Beirut's

old souk look like?

Suddenly a particularly striking aspect of all this planning becomes

quite clear. Assuming all goes well and the souk gets "rebuilt," it will only

be a matter of years before the generation of Lebanese that remembered

the old souk, the old Beirut, will be gone. The souks and the old down-

town have been gone since 1975, after all; people of my own generation

can barely remember what they were like, and anyone born after 1970 or

so can have no idea at all what the souks were like. (I myself have only a

few sketchy memories.) Of course one could go offto Tripoli or Damascus

or Aleppo to see what other Arab souks are like, or to Istanbul or other

cities in the region to see what other Levantine souks look like; but it is

in the "nature" (if I may use that language) of souks that each one has its

distinctive identity and even that different souks in the same city have

. . . * * s * -

thelr own c .lstlnctlve ldentltles.

Then why call this area a souk? Why not just call it a shopping dis-

trict, like Baltimore's Inner Harbor or other such projects in the U.S. and

Europe (of which Disney's U.S. history theme park near Washington,

D.C., would have been another variant), in which time and history as

much as more "material" objects get commodified and effectively put up

for sale and consumption? After all, just as MTV and CNN jockey for

position on Lebanese airwaves, the streets of Beirut are already witness

to an astonishing proliferation of American global consumer-culture out-

lets. Here the logic of the simulacrum becomes almost inescapable. Guy

Debord's famous slogan from The Society of the Spectacle, "the image has

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

C"tical Inquiry Spring 1997 687

.

HW 9 f t

_

&t_,,@., 4 -, 1 N jzt l S > @y!g z

911 e15 ^z nl Q

eWl;SSg ) CLD,_- 2s Ay

v p , . , ,J_ s , , ' _ ! _ J ,sJ sN -1 J , 5 S- j-t-i v iv) | o2-- ^ - !! >; 5J # ! ! ^ LL _ i l e J * i i K . _ | ; ^ '!, S ' s S S D' c! _ j .tS 5 _ _J * IWU *<\S;*S _ s -> _ _wA, j J S;4 ,! a; L] | FX 4 ; q lEW e j a s ;i ;_1 Ai Yi =z1 _ 'eu u !4 ,Ji _1k!J__L 1 - W FJ JIYSFJS

J J ;n}- - < - - <-< | .:--; e : | >: SE ,,.,_. S . ,,

;J_>_l i= >_a _O si.-E. --A8 ] LJ h>J j _ p <S;2Nt _e;E _ 4 --a_' S i e_'. | ,.,!E . ;; <,J4u_, y ' t . ewrsr. j j D J ! a _ | _ _ l _ 4 _ i b i ^-- 5t _e L z; i -::SJ i e i: s , e ll' _._ % I i u @ v.aI O - ;-n .......... s s J i : ! ' t * | s J .1 -_ ) ; , C_ _, i, _, [ g @ ;. . t to _ !o .-_[ 5 L!z; S # fO; _# -; .#H 4_>_ I ^ ,, t t

FIG. 20.-From one of the Solidere booklets. Note how the photo has been inserted

into the margin and seems to protrude from underneath the text, an bunderneath" that

does not exist. Source: Solidere.

become the final form of commodity reification,"26 is, as Fredric Jameson

has argued, now

even more apt for the "prehistory" of a society bereft of all historicity,

one whose own putative past is little more than a set of dusty specta-

cles. In faithful conformity to poststructuralist linguistic theory, the

past as "referent" finds itself gradually bracketed, and then effaced

altogether, leaving us with nothing but texts.27

What will presumably appear in a few years as the new Beirut "souk" will

present itself as recapturing and re-creating the old souk, the lifestyle of

happy customers and ask-no-questions merchants (that is, harking back

to the myth of the Levantine entrepot, to the happy Lebanon of the good

old days, to a never-never land that has only ever existed in Solidere's

booklets), and hence it will claim to re-present the past and the historical

collective memory of the old Beirut souks in its own spatiality. It will ap-

26. Quoted in Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism

(Durham, N.C., 1992), p. 18.

27. Ibid.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

688 Saree Makdisi Laying Claim to Beirut

pear or, to be precise, it will be marketed as a re-creation of what was

there before, rather than as something that is entirely novel, something

that, properly speaking, has no historical depth because it has no past at

all, because it is part of a much broader process that has from the begin-

ning tried to strip away the past and lay bare the surface of the city as

sheer surface spectacle and as nothing more than that.

Indeed, the representation of the past in visual or iconic terms is a

recurring theme in Solidere's various information booklets. One of these

booklets, appropriately entitled Wasat al-tasaoulat (The Center of Contro-

versy), published in 1993 in response to various criticisms of the recon-

struction project, incorporates visual references to the past by including

thin slices of old photographs inserted at the inside margins of its pages.

The visual effect is to make it seem as though there is an old photograph

"underneath" each facing page, which is only partly protruding (so that

you can barely determine the content of the photograph; because it is

grainy and black and white, all that's clear is that it is of something old).

But if you try to turn the page to see the rest of the photo, you realize

that it's not there after all; it just seems to be there, as though it were

serving as the figuration of some kind of iconic or visual unconsciousness

of the book: there, but not there, an absent presence. As soon as you try

X :ffff; tt ,j ; -->

Si , i

.. w j .w)

s 4jssJ > ! t

B . - ^e ^oFr x . M A <'' ^ ........................................ ^

; <> 694/i g t;>4 1 t>*gqsf s < > r E v

::

Sj s

FIG. 21. The cover of Beirut: Do We Know itt Note how the characters are pointing

towards one of Solideres own sketches of Beirut as though it were real (see fig. 12). The

word Beirut as it appears on the cover is the company's logo. Source: Solidere.

n ..

t, . :..

\..

:.. \\

.:}'Sw

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Critical Inquiry Spring 1997 689

to get access to the full "image" of the past (for as I say the past is pre-

sented only in visual terms), you realize that it's only a fragmentary im-

age, a fragment of a larger whole that has disappeared "underneath" the

weight of the "present" text, and that there is no "underneath" from

which the print appears to protrude because the text itself is literally as

well as metaphorically depthless.

But undoubtedly the most interesting of Solidere's booklets is the

one called Beirut: Do We KnozlJ It? This colorful little booklet seems to be

aimed at a juvenile audience, given not only its cartoon format but above

all its storyline. Its premise is that a little boy called Farid wants to know

"what this city is." He asks his mother to explain. Here it is worth quoting

at some length the initial dialogue that sets up the storyline.

What is this city?

I was involved in organizing my things and had not been paying

attention to what Farid was doing. I looked up at him.

What city, Farid?

This one!

And he pointed to a photograph album that he had taken from

my table. I craned my neck to see where his finger was pointing.

That's Beirut, Farid!

Beirut>!

-le$e *

tfet, k 12 [ii - _t_j

. . z .fP >4gJ t, E r _I * _E t E X R @ S *S fts4X - " i I " E | i 9jJ rJd ;j4*@s;2 ; w F ! ' : ! ^. r, _ - j _|: - * ... St Si Cl_tl si z ,Wi waLr ......................... .. , ._

* .s =w .1 ._e - w

., . . V; i_ 4 .,,_ .

= ! L . s

", LL . _ ai _ L E 9.. i _

^ . .

z-se. . s s ; 4 >ix ii i: e - :-t J . ,.+.'.. -S z ... . . - - r 1 S

o9, ,:.:: ., ^ in < aw

;^S_ .. 2SS

si Lia fh - gE e N X * d r -i _iS t . ; W

FIG. 22. Opening pages of BeiruZ: Do We Know It? Note the postcard of Martyrs'

Square in the top left; see fig. l(b). Source: Solidere.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

690 Saree Makdisi Laying Claim to Beirut

At this point in the text we see a reproduction of a classic postcard of

Martyrs' Square from before the war. The storyline resumes:

He looked up at me in surprise. And he said:

We live in Beirut. And I've never seen these buildings in my

life!

I smiled. His life, which had begun during the war! How could

he believe that this was indeed Beirut? So I explained.

-These are pictures of Beirut from before the war. Of course

you've never seen it.

And I turned over a few of the pages.

-Especially these, Farid; these are pictures of the heart of Bei-

rut. And all you and your friends know and experience are its ex-

tremities, like the extremities of the body.

He asked:

-And is the city like a body?

-Exactly like a body. A city is born, it grows, it changes, exactly

like a body. And it's the same with Beirut, our beloved city.28

It becomes clear that the booklet's storyline involves Farid taking a tour

of the old Beirut. This is in other words not merely a narrative of the

history of Beirut as Solidere would like that history to appear but a full-

blown guidebook, complete with a map, a legend, and a route that should

be followed through the center of the city, with descriptions of the various

significant structures or ruins given along the way.

There is just one problem with this guidebook: the area which it

proposes to guide young Farid through no longer exists. Published in

1994-even as the center of Beirut was being wiped clean by Solidere

itself-this booklet amounts not merely to a children's history of the cen-

ter of Beirut but to a guidebook whose referent has disappeared and has

been replaced by the textual images that the book itself contains. It is a

guidebook to a space that can no longer be found anywhere except in the

sort of textual (and specifically visual) forms that so dazzle little Farid.

One can only imagine a real-life Farid taking the map and guidebook

downtown and trying to follow the meandering route that it charts

through a wasteland that has taken the place of the actual material build-

ings that once stood there. Or did they?

As this little guidebook gets closer to the present and starts dealing

with the war, we are presented with various dazzling examples of

computer-generated graphics. Above a photo of Allenby Street as it was

left after the street fighting, for example, there is a computer-generated

photo of the same street as it is supposed to appear after it has been

refurbished and cleaned up. The computer image is clearly based on the

same wartime photo (for example, the perspective and the borders in

28. Solidere, Beirut: Hal na'arafha? [Beirut? Do We Know It?] (Beirut, 1994), pp. 2-3.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Critwal Inquiry Spring 1997 691

, *i S; r ^ . ii ,, ';,4. *8.-,9 ' : ,r: Xr.r ;- iOJ J ti e < : r :'

' 0 i 4+ X ......................... , . ! j ., > < _ _ C I ^ ae g S 1 ) 1 t ' @ ' ; * i - z S . . . . , .................... _ ,,., ,4 . _ f T ;/s ,.! i-'4, .... :

; 0 -t -d j b St R tt - j -,; t V

_ .

FIG. 23. Guidebook and map in Beirllt: Do We Know Itt Note that the area that it

proposes to guide people through no longer exists except in such textual form. Near the

top right of the map, for example, note one of Solidere's own artist's impressions of what

that area will look like a view reproduced in fig. 11. Source: Solidere.

each of the images are identical). However, this photograph of a simu-

lated future just as easily could be of the old prewar Allenby Street (that

is, there's nothing particularly futuristic about it; it looks like the same

street as in the wartime photo only without the damage and with the

addition of a few cars, a few trees, and some tastefully interspersed pedes-

trians). Hence, once again, Solidere's slogan: Beirut An Ancient City for

the Future, in which future and past become all but indistinguishable,

the one a replication of the other, only it is not clear which is the replica-

tion and which the original or whether there was an original to begin

with.

What the Solidere project represents, in a sense, is an attempt to

spectacularize history. Thus what might have been called the flow of Bei-

rut's past or the collective memories of the city are worked into the Soli-

dere proposals and booklets solely in visual form, in a pastiche version of

the history of central Beirut and of Lebanon, one that in representing

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Sat, 23 Aug 2014 12:28:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

692 Saree Makdisi Laying Claim to Beirut

the imposition of spatial layers in corporeal terms as the "growth" of a

single "body" translates the passage of time into appearance, into spec-

tacle.29

And yet it is worth asking what alternatives there might have been to

all this or what alternatives there might still be and whether alternative

conceptions of history are still possible.30 In retrospect, it becomes quite

clear that from at least 1983 there has been a concerted effort to wipe the

surface of central Beirut clean, to purify it of all historical associations in

the form of its buildings, to render it pure space, pure commodity, pure

real estate. The most obvious and striking potential war memorial (in a

country that has all but forgotten its war), the shrapnel-scarred statue in

Martyrs' Square, will be completely repaired its bullet holes erased and

covered over just as the historical referents in the city center (and history

itself) are being erased in the reconstruction. And in one sense the demo-

lition crews and the powerful financial interests standing behind them

have produced an irreversible fait accompli. Thus, what becomes im-

portant at this stage isn't the material construction, as such, but rather

what the construction project represents and how it ties into other pro-

cesses and other discourses in Beirut, in Lebanon, and in the world. What

I want to address now is the political-discursive modes through which

this activity inscribes and makes interventions in the surface of the city.

3. "Enrichissez-vous!" Or, Let Them Eat Cellular Phones

"'Enrichissez-vous!' Tel semble bien etre le coeur de l'ideologie de la

reconstruction."3' Thus writes the economist and historian Georges Corm

in a recent issue of Les Cahiers de l'Orient. In the same issue of the journal,

the urban sociologist Nabil Beyhum argues that the Solidere project rep-

resents an embodiment of the "confusion" of public and private interests

symbolized by the arrival in power of Hariri and his cabinet.32 Indeed,

29. Here it becomes important to bear in mind the distinction that Jameson makes

between parody and postmodern pastiche. See Jameson, Postmodernism, or, the Cultural LogXc

of Late Capitalism, p. 17.

30. The latter question, the question of history, I plan to take up in a different essay,

"Remembering Beirut: The Space of Memory and the Time of War."