Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Implementing Best Practices in Online Learning

Uploaded by

ChuckiedevOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Implementing Best Practices in Online Learning

Uploaded by

ChuckiedevCopyright:

Available Formats

R E S E A R C H

I N

B R I E F

Implementing Best Practices

in Online Learning

A recent study reveals common denominators for success in

Internet-supported learning

By Rob Abel

nline learning has made great

strides in higher education in

the past ve years, with wide

adoption of course management platforms such as Blackboard, WebCT, eCollege, and Angel, as well as emerging open

source solutions. Many institutions are

still unclear about how this new technology ts with their mission, however,

and have found that achieving widespread adoption by faculty is difcult.

They have also found it challenging to

achieve faculty use that truly enhances

the learning interaction between faculty

and students as opposed to simply posting materials online. Some studies have

reported dramatic growth of online

courses, but what is really going on?

A recent study by the Alliance for

Higher Education Competitiveness,

Achieving Success in Internet-Supported

Learning in Higher Education: Case Studies

Illuminate Success Factors, Challenges, and

Future Directions, pulled from the experiences of 21 institutions across all Carnegie classications to provide insights

into best practices for achieving success

in online learning. More importantly

for higher education leaders, the study

identied some potential root causes of

success (or lack of success). These common denominators of success (see Table

1) provide a framework for understanding why some initiatives succeed while

others do notand what conditions can

be created to make improvements.

Motives and Leadership

The 21 institutions selected to participate in the research described themselves

as being successful in online learning:

ve community colleges, seven baccalaureate/masters institutions (ve private, two public), and nine research/

doctoral institutions (one private, eight

public). While success in online learning is clearly a subjective indicator, participants included institutions ranging

from Penn State, which supports some

62,000 students with online technology, to Peirce College, whichwhile

much smallergenerates 46 percent of

its revenue from online programs.

Successful institutions had compelling reasons to support online learning.

The primary motivation is a desire to

increase service to students in a way

consistent with their needs and the mission of the institution. This alignment

between student service and mission

can take many forms:

The mission component to serve

working adults coupled with the

strong need of these students to have

more exibility in receiving effective

instruction.

The mission component to serve

more students coupled with the need

to keep costs reasonable for students.

This can be achieved in a number of

ways, one of which is to use online

technology to eliminate the need

Table 1

Ingredients for Success

Ranked Most

Important

Characteristic

Executive leadership and support

15%

Faculty and academic leadership commitment

15%

Student services

12%

Technology infrastructure

12%

Course/instructional quality

9%

Financial resources and plan

9%

Training

7%

Adaptive learn-as-you-go attitude

7%

Communication

5%

Marketing

4%

Other

4%

Number 3 2005

E D U C A U S E Q U A R T E R LY

75

for additional physical classroom

space.

The mission component to provide

a more personalized learning experience for students by using online

technology to support things like

increased collaboration, ability to

replay lecture portions on demand,

or bring in subject experts virtually to

increase the breadth of the learning

experience.

The study also indicated a predominant leadership style that most likely

contributed to the success in achieving

mission alignment. The key leadership

elements were

A long-term commitment to the initiative

Investment of signicant nancial

and other resources

Prioritization of expenditures on

high-impact programs

A clear understanding by faculty of

why the institution is implementing

online learning

In particular, the involvement of key

leaders in prioritizing where to focus

online learning development activities

was critical and highly correlated with

perceived success in these institutions.

What form did prioritization take?

Study participants repeatedly said that

the best strategy was to start with your

strongest programs, ideally the ones for

which you are nationally ranked (or

have some other distinguishing characteristic) and have a proven demand. Do

not look for a market where you do not

have a track record of success. In essence,

most institutions already have the best

market researchtheir existing record.

Some did benet from national market

research to decide whether to expand

beyond the local area. A renewed focus

on a once-growing program now losing enrollments was also a strategy that

worked for some.

Study participants, when asked if a

widespread perception existed that the

institution was committed to online

education, answered that there was no

doubt. They also indicated that past

nancial support was adequate and

future nancial support was apparent.

In other words, online learning was not

a one-time event or investment.

76

E D U C A U S E Q U A R T E R LY

Number 3 2005

Focus on Programs

Probably the most signicant nding

was that institutions that focused on

putting full programs online were about

four times as likely to perceive that they

had achieved overwhelming success

as institutions that focused their efforts

at the individual course level. Putting

a full program online, when done correctly and focused on student learning,

involves teamwork within the academic

department and among several units of

the institution. For the online program

to succeed, it must be thought through

carefully and perhaps reengineered to

serve students differently and, hopefully, better.

The most common success factors of

those institutions implementing the

programmatic approach include

Support resources dedicated to the

selected program(s) (93 percent)

Development of a project plan,

including schedule and milestones

(87 percent)

Prioritization from institutional leadership to choose programs having the

most impact (86 percent)

Program redesign sessions to help faculty leaders create a better program

(74 percent)

Pedagogy defined to reflect the

uniqueness of the program(s) (73

percent)

Involvement of enrollment management in the program planning (67

percent)

Development of success measures,

such as enrollment targets (67

percent)

Looking at the factors, one could

say that much of this was just good

management, but it is also clear that

these institutions are implementing

new course and program formats to

reect the unique pedagogy of their

program and/or institution. In other

words, they are doing a lot more than

just posting course notes or syllabi

online. They are creating a more effective learning experience at the program level.

While the predominance of online

activity today is of the simple syllabiposting type, referred to in the study as

Web-supported courses, this was not

true in the study institutions. When

asked where they expect to spend more

effort in the future (Which of the

online course types do you see gaining

in relative importance at your institution in the next three years?), they

responded as shown in Table 2.

Faculty Support and

Student Services

In online learning, faculty are asked to

make the biggest changes, with unclear

rewards. The programmatic approach

provides a framework that supports

faculty working together to create a

better student experience. Today, a

quality online learning experience still

has much more to do with the faculty

member teaching the course than anything else. Its still the teaching, not the

technology.

So, how can an institution support

faculty involved in online learning

endeavors? The study elicited the following best practices:

Nurture grass-roots faculty ideas.

Make sure they are at the center as

programs move online, and ensure

that all faculty who want to venture

online have the support services they

need.

Provide frequent and clear communication on why the move to

online is important to the institutional mission.

Provide faculty with support in online

technology and pedagogy so that

Table 2

Increasing Importance by

Course Type

Course Type

Increasingly

Important

Fully online

67%

Hybrid

61%

Online or hybrid at

corporate sites

11%

Web-supported

11%

High-enrollment

introductory or

other

6%

Dont know

6%

they can focus on using the tools

to enhance their interactivity with

students.

Provide one-on-one instructionaldesign consultations along with

staff-development classes that require

faculty to experience online courses

from the student perspective and to

develop their own online courses.

Recognize the scholarship of teaching and the improved quality it

promotes.

Several study participants indicated that one of their most important lessons was to take into account

the complete set of student services

required for students to receive more

of their education online. Across all

the participants, student services tied

for third for an open-ended question

regarding the most important factors

in achieving success.

Course materials must be available

and easy to use, and students must have

someone to call when they need technical help. A new trend was to establish

a contact point for resolution of any

student issue. This individual went by

many names, such as program coordinator or advisor. Other student support

services predominant at the successful institutions are discussed in the full

study.

Goals and Measurements

Table 3

Metrics of Success

Category

Ranked

Important

Student outcomes

29%

Student satisfaction

21%

Growth in

enrollments

21%

Faculty satisfaction

10%

Return on

investment

5%

Number of courses/

sections

4%

Other

10%

2. Do you have an effective executive

review process, formal or informal,

to prioritize the program selection,

faculty selection, and support activities to move online? Are you committed to supporting these activities

over the long term?

3. Are you focusing most of your effort

at the program level? Are you redesigning programs so that they are

enhanced by fully online or hybrid

delivery?

4. Are grass-roots faculty efforts being

supported along with the programmatic priorities? Are faculty sup-

ported in learning how to transform their teaching expertise to the

online environment?

5. Are you providing highly reliable

and easy online access for students

coupled with a single point of

contact that can resolve issues or

concerns?

6. Have you established quantiable

metrics that are balanced between

quality and growth? Have you set

objectives that demonstrate consistent progress?

The study results imply that, taken in

total and roughly in order, positive

answers to these questions will result

in substantial progress and success in

online learning in higher education.

The full study is available online

at <http://www.a-hec.org/e-learning_

study.html>. It contains proles and

contact information for each of the 21

participating institutions, 60 pages of

in-depth results, and a bibliography of

25 references. A follow-on studyopen

to all institutionsthat facilitates a selfaudit is described at <http://www.a-hec

.org/IsL_2005.html>. e

Rob Abel is the president and founder of the

Alliance for Higher Education Competitiveness

(A-HEC), a nonprot organization dedicated

to research into innovation, transformation,

and effectiveness in higher education.

The majority of institutions in the

study felt they had done better than

they initially expected. Generally, they

expected growth in the range of 15 to

25 percent. Most explicitly stated the

paramount importance of balancing

quality with growth.

What measures of success did the

study institutions use? As shown in

Table 3, fully 50 percent focused on

student outcomes and satisfaction.

Key Lessons

How can you tell if your initiatives

stack up? The following questions

should give you important insights into

where you can improve:

1. What key mission objective, aligned

with a primary student need, will be

the focus of your online learning

activities?

Number 3 2005

E D U C A U S E Q U A R T E R LY

77

You might also like

- Evaluating Your College's Commitment to the Recruitment & Retention of Students of color: Self-Evaluation InstrumentFrom EverandEvaluating Your College's Commitment to the Recruitment & Retention of Students of color: Self-Evaluation InstrumentNo ratings yet

- Ehrhardt Oesis Mechanics of Online EdDocument21 pagesEhrhardt Oesis Mechanics of Online EdJonathan E. MartinNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Teaching-Learning Process in Online Education As Perceived by University Faculty and Instructional Technology ProfessionalsDocument11 pagesThe Effectiveness of Teaching-Learning Process in Online Education As Perceived by University Faculty and Instructional Technology ProfessionalsHenry James NepomucenoNo ratings yet

- Concept Testing and Prelaunch Study of Online Mba Degree ProgramDocument42 pagesConcept Testing and Prelaunch Study of Online Mba Degree ProgramNumair Imran0% (1)

- BC Funding Model 2019Document11 pagesBC Funding Model 2019Jeffrey VuongNo ratings yet

- Effective Practices Snapshot: Student Services For Online LearnersDocument8 pagesEffective Practices Snapshot: Student Services For Online LearnersBlackboardInstituteNo ratings yet

- Submitted To:: Gopal Bihari Saraswat Department of Management StudiesDocument20 pagesSubmitted To:: Gopal Bihari Saraswat Department of Management Studiesmukta sagarNo ratings yet

- Edu699 - Final Report Share FairDocument14 pagesEdu699 - Final Report Share Fairapi-310755606No ratings yet

- 04T04-Standards Online Prof DevDocument8 pages04T04-Standards Online Prof DevMoh AbdouNo ratings yet

- Accenture Digital Learning Business Case ToolDocument6 pagesAccenture Digital Learning Business Case ToolJessica MartinezNo ratings yet

- 2015 Wasc Action PlanDocument10 pages2015 Wasc Action Planapi-237056229No ratings yet

- 8462 - Wyatt - P1 Annotated BibliographyDocument21 pages8462 - Wyatt - P1 Annotated BibliographyPaula N Tommy WyattNo ratings yet

- Establishing A Quality Review For Online CoursesDocument17 pagesEstablishing A Quality Review For Online CoursesMJAR ProgrammerNo ratings yet

- Capstone Report Final Margo Tripsa!Document12 pagesCapstone Report Final Margo Tripsa!Margo TripsaNo ratings yet

- IHE FacultySurvey FinalDocument35 pagesIHE FacultySurvey FinalPedro TebergaNo ratings yet

- Report of The Remediation Working GroupDocument26 pagesReport of The Remediation Working GroupSoun SokhaNo ratings yet

- The Future of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education:: OnlineDocument9 pagesThe Future of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education:: OnlineKaiteri YehambaramNo ratings yet

- iNACOL - Blended Learning The Evolution of Online and Face To Face Education From 2008 2015 - 2 PDFDocument20 pagesiNACOL - Blended Learning The Evolution of Online and Face To Face Education From 2008 2015 - 2 PDFaswardiNo ratings yet

- Are You Ready To Teach Online SurveyDocument10 pagesAre You Ready To Teach Online SurveyParti BanNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting To Effective Elearning: Learners PerspectiveDocument7 pagesFactors Affecting To Effective Elearning: Learners Perspectiverobert0rojerNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Online Learning Platforms' Efficacy On Student'S Engagement and Learning OutcomesDocument10 pagesEvaluating Online Learning Platforms' Efficacy On Student'S Engagement and Learning OutcomesLiand TanNo ratings yet

- MI High School Online Learning RequirementsDocument20 pagesMI High School Online Learning RequirementsLaura_C100% (2)

- Cur 532 W 6 KatzDocument19 pagesCur 532 W 6 Katzapi-321391037No ratings yet

- Carol Twigg New Models For Online - LearningDocument8 pagesCarol Twigg New Models For Online - LearningformutlNo ratings yet

- Evaluationprocess Cur528 wk6 DanobriienDocument7 pagesEvaluationprocess Cur528 wk6 Danobriienapi-324079029No ratings yet

- E-Learning Benchmarking Survey: A Case Study of University Utara MalaysiaDocument8 pagesE-Learning Benchmarking Survey: A Case Study of University Utara MalaysiaMarcia PattersonNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Online Teaching and LearningDocument3 pagesIntroduction To Online Teaching and LearningZelster Zee NeriNo ratings yet

- Conlon 1997Document11 pagesConlon 1997AngelooNo ratings yet

- Research MethodologyDocument6 pagesResearch Methodologyà S ÀdhìkãríNo ratings yet

- Principles of Good Online Assessment DesignDocument6 pagesPrinciples of Good Online Assessment DesignDr.Fouzia KirmaniNo ratings yet

- Netp 17Document111 pagesNetp 17api-424461517No ratings yet

- 6 OnlinelearningproposalDocument2 pages6 OnlinelearningproposalHoorya HashmiNo ratings yet

- Huang Mapb v5 Day CareDocument15 pagesHuang Mapb v5 Day CareJosue Claudio DantasNo ratings yet

- CAA As Innovation Capable of Affecting ChangeDocument8 pagesCAA As Innovation Capable of Affecting Changern593772No ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Transformative Curriculum Design EDIT2Document50 pagesChapter 2 Transformative Curriculum Design EDIT2Noey TabangcuraNo ratings yet

- Project 1 ONE LitReview Exec SumDocument7 pagesProject 1 ONE LitReview Exec Sumgeorgian3060No ratings yet

- Kauffman (2015) - A Review of Predictive Factors of Student SuccessDocument20 pagesKauffman (2015) - A Review of Predictive Factors of Student SuccessJelicaNo ratings yet

- Pchs Sit 15-16Document7 pagesPchs Sit 15-16api-260589859No ratings yet

- Students' Perception of Online AssessmentsDocument16 pagesStudents' Perception of Online Assessmentsname lessNo ratings yet

- Ed 807 Economics of Education MODULE-14 Activity-AnswerDocument3 pagesEd 807 Economics of Education MODULE-14 Activity-Answerjustfer johnNo ratings yet

- Blended LearningDocument16 pagesBlended LearningKartik KumarNo ratings yet

- RRL 1Document4 pagesRRL 1Thricia Lou OpialaNo ratings yet

- READINESS: Re-Thinking Educational and Digital Innovation Necessary For Ensuring Student SuccessDocument5 pagesREADINESS: Re-Thinking Educational and Digital Innovation Necessary For Ensuring Student Successapi-301850548No ratings yet

- Teaching Children Well Teaching Children Well: ErrorDocument25 pagesTeaching Children Well Teaching Children Well: ErroromiNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Modular KitchenDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On Modular Kitchenfvf2j8q0100% (1)

- Guidelines For Observation of Online TeachingDocument16 pagesGuidelines For Observation of Online TeachingIriskathleen AbayNo ratings yet

- Bento, R. F., & White, L. F. (2010) - Quality Measures That Matter. IssuesDocument6 pagesBento, R. F., & White, L. F. (2010) - Quality Measures That Matter. IssuesChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Week 4 Change ProcessDocument5 pagesWeek 4 Change Processapi-223837372No ratings yet

- What's Different About Teaching Online? How Are Virtual Teachers Changing Teaching?Document3 pagesWhat's Different About Teaching Online? How Are Virtual Teachers Changing Teaching?Naty TimoNo ratings yet

- Enhancing Teachers Distance Learning Competencies and Attitudes in The Time of Pandemic Through A Capability Building ProgramDocument6 pagesEnhancing Teachers Distance Learning Competencies and Attitudes in The Time of Pandemic Through A Capability Building ProgramPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- AbstractDocument1 pageAbstractBaffour JnrNo ratings yet

- Developing Digital Literacies ProgrammeDocument41 pagesDeveloping Digital Literacies ProgrammedrovocaNo ratings yet

- Original "The Effects of Internet-Based Distance Learning in Nursing"Document5 pagesOriginal "The Effects of Internet-Based Distance Learning in Nursing"Ano NymousNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Online Learning Based On The Academic Performance of IT Students in FEU-Institute of TechnologyDocument6 pagesEffectiveness of Online Learning Based On The Academic Performance of IT Students in FEU-Institute of TechnologyMarNo ratings yet

- Teaching Class Employee Performance and Development PlanDocument19 pagesTeaching Class Employee Performance and Development Planapi-298158473No ratings yet

- CREATE Conference 2009 PowerpointDocument18 pagesCREATE Conference 2009 PowerpointPandu NovialdiNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument37 pagesUntitledMichael NcubeNo ratings yet

- Study On Consumer'S Preference and Perception Towards Online EducationDocument20 pagesStudy On Consumer'S Preference and Perception Towards Online Educationmukta sagarNo ratings yet

- Blended LearningDocument18 pagesBlended Learningaswardi100% (2)

- Ist626 Qms 1 8Document58 pagesIst626 Qms 1 8api-265092619No ratings yet

- Management of ToolsDocument5 pagesManagement of ToolsChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Harvester 722Document6 pagesHarvester 722ChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Management of ToolsDocument5 pagesManagement of ToolsChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Web2 0ToolsEffectiveorNotDocument19 pagesWeb2 0ToolsEffectiveorNotChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Devlin AssignmentDocument7 pagesDevlin AssignmentChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Internship Time SheetDocument8 pagesInternship Time SheetChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Web2 0ToolsEffectiveorNotDocument19 pagesWeb2 0ToolsEffectiveorNotChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Charles Devlin Annotated BibDocument14 pagesCharles Devlin Annotated BibChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Blended LearningDocument24 pagesBlended LearningChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Internship Time SheetDocument8 pagesInternship Time SheetChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- HRTM Course ScheduleDocument6 pagesHRTM Course ScheduleChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Charles Devlin Final ReflectionDocument4 pagesCharles Devlin Final ReflectionChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Internship Time SheetDocument8 pagesInternship Time SheetChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Charles Devlin Annotated BibDocument12 pagesCharles Devlin Annotated BibChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Charles Devlin Annotated BibDocument14 pagesCharles Devlin Annotated BibChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Online Face To FaceDocument5 pagesOnline Face To FaceChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Charles Devlin Annotated BibDocument14 pagesCharles Devlin Annotated BibChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Designing Online Courses: A Taxonomy To Guide Strategic Use of Features Available in Course Management Systems (CMS) in Distance EducationDocument15 pagesDesigning Online Courses: A Taxonomy To Guide Strategic Use of Features Available in Course Management Systems (CMS) in Distance EducationChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Student ViewsDocument15 pagesStudent ViewsChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Singleton IheDocument12 pagesSingleton IheYoyoball BallNo ratings yet

- Computers in The Schools: Interdisciplinary Journal of Practice, Theory, and Applied ResearchDocument14 pagesComputers in The Schools: Interdisciplinary Journal of Practice, Theory, and Applied ResearchChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Distance LearningDocument30 pagesDistance LearningChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- EditorialDocument10 pagesEditorialChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Bento, R. F., & White, L. F. (2010) - Quality Measures That Matter. IssuesDocument6 pagesBento, R. F., & White, L. F. (2010) - Quality Measures That Matter. IssuesChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Intervention in School and Clinic 2010 Brunvand 304 11Document9 pagesIntervention in School and Clinic 2010 Brunvand 304 11ChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Internship Time SheetsDocument3 pagesInternship Time SheetsChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Equal Access: Universal Design of Instruction: by Sheryl Burgstahler, PH.DDocument6 pagesEqual Access: Universal Design of Instruction: by Sheryl Burgstahler, PH.DChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Internship Time SheetsDocument3 pagesInternship Time SheetsChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Internship ReflectionDocument1 pageInternship ReflectionChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Virtual en Gang EmentDocument9 pagesVirtual en Gang EmentChuckiedevNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Log in Computer Systems Servicing Data CommunicationDocument5 pagesDaily Lesson Log in Computer Systems Servicing Data CommunicationJonathan CordezNo ratings yet

- Dalis SBM 2018Document22 pagesDalis SBM 2018Ismael S. Delos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Authors Purpose Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesAuthors Purpose Lesson Planapi-316375975No ratings yet

- Authentic vs. Traditional AssessmentDocument3 pagesAuthentic vs. Traditional AssessmentAbegail CachuelaNo ratings yet

- CISA Demo ClassDocument13 pagesCISA Demo ClassVirat AryaNo ratings yet

- Theory Unit 32 - 1993 Listing - Updated 2017Document12 pagesTheory Unit 32 - 1993 Listing - Updated 2017LGFNo ratings yet

- Result - GTU, AhmedabadDocument1 pageResult - GTU, AhmedabadItaliya ChintanNo ratings yet

- Grade 10 T.L.E CUR MAPDocument6 pagesGrade 10 T.L.E CUR MAPGregorio RizaldyNo ratings yet

- II. Ecoliteracy and The Different ApproachesDocument34 pagesII. Ecoliteracy and The Different Approachesgerrie anne untoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2: Activity Based Teaching Strategies: Dovie Brabante-Ponciano, MAN, RNDocument17 pagesLesson 2: Activity Based Teaching Strategies: Dovie Brabante-Ponciano, MAN, RNjoseph manansalaNo ratings yet

- Asucq Tus/Alpha Program: Class Grade Breakdowns Comments GradeDocument1 pageAsucq Tus/Alpha Program: Class Grade Breakdowns Comments GradejesusNo ratings yet

- Ma. Fe D. Opina Ed.DDocument3 pagesMa. Fe D. Opina Ed.DNerissa BumaltaoNo ratings yet

- Study Guide For Module 1: Telefax: (075) 600-8016 WebsiteDocument32 pagesStudy Guide For Module 1: Telefax: (075) 600-8016 WebsitePrincess M. De Vera100% (5)

- The Nature, Structure, and Content of The K To 12 Science CurriculumDocument23 pagesThe Nature, Structure, and Content of The K To 12 Science CurriculumJhenn Mhen Yhon0% (1)

- Generic Management NQF5 Programme or Learnership 2017Document9 pagesGeneric Management NQF5 Programme or Learnership 2017LizelleNo ratings yet

- Physical Activities Towards Health and Fitness IV, ShortlyDocument7 pagesPhysical Activities Towards Health and Fitness IV, ShortlyVanessa Mae Mabansag DagantaNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Barretto Ii Elementary SchoolDocument8 pagesDepartment of Education: Barretto Ii Elementary SchoolJaycel Obina PalangNo ratings yet

- Coding Lesson Plan TemplateDocument2 pagesCoding Lesson Plan Templateapi-444425700No ratings yet

- 7 Types of TeacherDocument14 pages7 Types of TeacherHazel Jane MalicdemNo ratings yet

- College Readiness Self Assessment 2 1 1 1Document4 pagesCollege Readiness Self Assessment 2 1 1 1api-339158337No ratings yet

- ECE Lesson Plan Template AssignmentDocument3 pagesECE Lesson Plan Template AssignmentAeisha CobbNo ratings yet

- Field Study 1: Observations of Teaching-Learning in Actual School EnvironmentDocument12 pagesField Study 1: Observations of Teaching-Learning in Actual School EnvironmentAndrea MendozaNo ratings yet

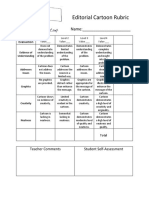

- Rubric EditorialCartoon PDFDocument1 pageRubric EditorialCartoon PDFMarilyn Claudine N. BambillaNo ratings yet

- Teaching English Through Songs and GamesDocument19 pagesTeaching English Through Songs and GamesTri Sutyoso HarumningsihNo ratings yet

- Short Story Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesShort Story Lesson Planapi-302202015No ratings yet

- Es Ol TKTDocument3 pagesEs Ol TKTNoël PereraNo ratings yet

- 4-Required Documents SunbeamDocument5 pages4-Required Documents SunbeamSanja Joshua von ZabuciNo ratings yet

- Syllabus On Elements of ResearchDocument13 pagesSyllabus On Elements of ResearchBrent LorenzNo ratings yet

- Use Propaganda TechniqueDocument2 pagesUse Propaganda TechniqueGeorma CaveroNo ratings yet

- Water Cycle JigsawDocument2 pagesWater Cycle Jigsawapi-372778638No ratings yet