Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Voss and Allen

Uploaded by

gems4emmaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Voss and Allen

Uploaded by

gems4emmaCopyright:

Available Formats

5

Barbara L. Voss

Rebecca Allen

Overseas Chinese Archaeology:

Historical Foundations, Current

Reflections, and New Directions

Abstract

As historical archaeologists increase their involvement in studies of Overseas Chinese communities, it is especially important

that this research be grounded in a solid understanding of the

history of the Chinese diaspora. A transnational framework is

instrumental in facilitating an understanding of the ways in

which Overseas Chinese communities and identities formed

through global economic, political, and cultural networks.

The archaeology of Overseas Chinese communities currently

faces many challenges, including underpublication, a tendency

towards descriptive rather than research-oriented studies, and

orientalism. These difficulties are being surmounted through

collaborative research programs that foster dialogue between

archaeologists and Chinese heritage organizations, as well

as through interdisciplinary exchanges that are forging new

connections among historical archaeology and Asian American

studies and Asian studies.

Introduction

Although a few important pioneering archaeological studies of Overseas Chinese communities

were undertaken in the late 1960s and 1970s, it

was not until the 1980s and 1990s that Overseas

Chinese archaeology emerged as a distinct topic

of inquiry in certain U.S. states and in Australia and New Zealand. The first years of the

current decade have witnessed an exponential

proliferation of archaeological investigations of

Overseas Chinese communities throughout the

world. With rare exceptions, these studies have

not yet attracted the attention of the discipline

as a whole. Many of the research topics that

figure prominently in historical archaeology

immigration, racialization, the expansion of

capitalism, labor relations, ethnic and national

identities, gender and sexuality, urbanization,

and consumer culture (to name a few)cannot

be fully investigated without considering one of

the worlds largest population movements, the

19th- and 20th-century expansion of the Chinese

diaspora. The study of Chinese immigration and

Chinese diaspora communities, and their effects

on demography, economy, and social life on

both global and local scales, can illuminate

new perspectives on well-trodden archaeological

avenues of inquiry.

The articles and resources presented here demonstrate that Overseas Chinese archaeology is

presently at a point of transformation. Paradoxically, Overseas Chinese archaeology is coming of

age at a time when archaeologists are re-examining the conceptual foundations that underpinned

archaeologies of ethnic and racialized groups.

Anthropologists and sociologists have challenged

the empirical validity of biological race since

the beginning of the 20th century (Boas 1912;

American Association of Physical Anthropologists 1996; American Anthropological Association

1998). Racialized categories are scientific fictions

that function as social facts (Durkheim 1982).

Contrary to what appears in some archaeological literature, there is no Chinese race. The term

Chinese in its broadest sense is a nationality, one

that encompasses an immense range of human

biological, linguistic, ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity.

An inheritance of past injustices, the social

facts of race and racism are reconfigured and

re-created in the present, an observation that

has led some archaeologists to reflexively query

how archaeology has participated in the social

production of race and racism (Spector 1993;

Franklin 1997; Orser 2004; Lucas 2006). Ethnicity, at times embraced by archaeologists to

sidestep the conundrum of race, has similarly

been destabilized. Since Fredrik Barths (1969)

seminal thesis on ethnic boundaries, social scientists have long recognized that there is nothing essential or stable about cultural, ethnic,

or national traditions (Sollors 1986; Anderson

1993). Instead, racial and ethnic identities are

increasingly understood as being produced

through power-laden negotiations of the tension

between sameness and difference.

Rather than investigating Chinese identity or

Chinese culture, archaeologists will be better

served to investigate how cultural practices

participate in the ongoing production of

identities and communities and, in doing so, to

understand ethnicity as historically constituted,

Historical Archaeology, 2008, 42(3):528.

Permission to reprint required.

Main Body-42(3).indd 5

2/7/08 2:35:21 PM

sustained, and transformed (Lowe 1996). Recent

social theories point archaeologists to hybridity,

ambivalence, and cultural borderlands in their

investigations of social identity, race, and

ethnicity (Hall 1989; Chin et al. 2000; Okihiro

2001; Prashad 2001, 2006; Meskell 2002;

Bhabha 2004; Lucas 2006). A polycultural

approach examines the cultural interplay within

and among ethnically and racially marked

populations, correcting against the tendency to

envision Chinese communities as bounded or

insular (Prashad 2006). As Stuart Hall (1989)

enjoins, those studying race and ethnicity

must develop methodologies that engage with

cultural difference while resisting the tendency

to perpetuate the segregation and subjugation of

peoples based on race and ethnicity.

This introductory article is intended not

only to introduce the reader to the studies and

resources presented in this volume but also to

acquaint archaeologists with the vast historical

and conceptual scholarship on the Overseas

Chinese that has been achieved in other disciplines. Although Overseas Chinese archaeology

is still developing, archaeologists are fortunate

that many of the challenges involved in such

research have already been encountered by historians of the Chinese diaspora and by scholars

in Asian studies and Asian American studies.

Their theoretical and interpretive frameworks

can guide archaeologists in their disciplines

growing involvement in scholarship on Overseas

Chinese communities.

Chinese Immigration and Settlement in the

United States: History and Historiography

Emigration from southeastern China during the

last few centuries is one of the most important

population movements of modern history. Historians trace southeast Chinese immigration to the

7th century with the beginning of Chinese trade

throughout the South China Sea and, beginning

in the 16th century, the east coast of Africa.

Large-scale immigration began in the early 1600s

with tens of thousands of Chinese relocating to

Thailand and the Philippines. Emigration accelerated during the last half of the 19th century,

with more than 2.5 million people leaving China

for destinations throughout the world (Chan et

al. 1991; Takaki 1998:32; Pan 1999; McKeown

2004). A sizeable portion of these people immi-

Main Body-42(3).indd 6

HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 42(3)

grated to the U.S. mainland (380,000) and the

Kingdom of Hawaii (46,000), with the rest

arriving in Canada, Mexico, Cuba, the West

Indies, Central and South America, New Zealand,

Australia, Southeast Asia, and Africa (Takaki

1998:32). Transnational scholarship on the history

of Overseas Chinese immigration and diaspora

reminds archaeologists to be extremely cautious

to not overgeneralize the activities and experiences of Chinese immigrants in specific locales

(Pan 1999; Peffer 1999; Hsu 2000; McKeown

2001; Lee 2003). This thematic issue, with its

focus on the present-day United States, must be

understood as a window into the specific experiences of the Chinese who immigrated into lands

dominated by the legal, economic, demographic,

and cultural environments of the United States

and U.S.-based agricultural capitalism in the

Kingdom of Hawaii. It was within this specific

environment that Chinese immigrants and Chinese

Americans came to have profound impacts on

the shape of American history and culture (also

Baxter, Table 1, this volume).

Why Immigrate? Origins,

Inducements, and Objectives

The vast majority of Chinese people who

immigrated to the U.S. and the Kingdom of

Hawaii during the 19th century came from

Guangdong (also commonly transliterated as

Kwangtung) province, specifically from the Pearl

River Delta region near the port city of Guangzhou (Canton) (Figure 1). Guangzhou was the

site of centuries of cultural and economic relations with non-Chinese, which opened pathways

for international trade, travel, and immigration

for Pearl River Delta residents. In 1844, the U.S.

acquired trading privileges with China through

the Treaty of Wang Hya. Guangzhou was designated one of the five Chinese ports in which

U.S. traders could operate, leading to the rapid

development of business partnerships and commercial relationships between U.S. and Chinese

merchants and regular ship movement between

Guangzhou and U.S. ports.

Nearly all 19th-century Chinese immigrants

to the U.S. and the Kingdom of Hawaii originated from eight counties adjacent to Guangzhou

(Figure 2). Historians estimate that 80 to 90%

came from the Siyi (Sze Yup) districts, comprised

of the Taishan (also Xinning), Xinhui, Kaiping,

2/7/08 2:35:21 PM

BARBARA L. VOSS AND REBECCA ALLENOverseas Chinese Archaeology

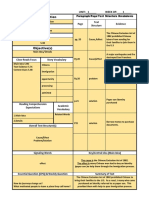

TABLE 1

KEY LEGISLATIVE, JUDICIAL, AND HISTORICAL BENCHMARKS IN CHINESE AMERICAN

AND CHINESE HAWAIIAN IMMIGRATION, 17901947

1790

Naturalization Law restricts naturalized United States citizenship to whites.

1802 Chinese entrepreneurs establish sugar works in Hawaii.

1844

United States acquires trading privileges with China through Treaty of Wang Hya.

1849 California Gold Rush begins.

1850 Royal Hawaiian Agricultural Society established by U.S.-based planters to recruit Chinese contract laborers to Kingdom

of Hawaii.

1854 California Supreme Court decision of People v. Hall determines that Chinese people are not legally white and cannot

testify against whites in courts of law.

1862 Six Chinese Companies formed through federation of district associations.

1868 Burlingame Treaty between U.S. and China grants federal recognition of Chinese to travel to U.S. as visitors, traders, or

permanent residents.

1870

Federal Civil Rights Act voids Californias Foreign Miners License Tax and Chinese Capitation Tax; extends rights of

contract law and court proceedings to Chinese and other Asian Immigrants.

1875

Federal Page Law prohibits immigration of Chinese, Japanese, and Mongolian prostitutes, felons, and contract

laborers.

1880

U.S. and China sign treaty giving U.S. right to limit Chinese immigration.

1882 Chinese Exclusion Act prohibited entry of Chinese laborers for period of 10 years, allowing only merchants and

professionals; Chinese wives and children of Chinese laborers also prohibited.

1882

Zhonghua Huiguan (Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association) formed.

1888 Scott Act limits re-entry ability of Chinese immigrants.

1892

Geary Act extends Chinese Exclusion Act for 10 additional years and requires Chinese residents of U.S. to register with

local authorities and carry certificates of lawful residence.

1898

Wong Kim Ark v. U.S. determines that U.S.-born Chinese cannot be stripped of their citizenship.

1898

U.S. annexes Kingdom of Hawaii; ends contract-system of plantation labor and applies Chinese Exclusion Act to

Territory of Hawaii.

1902 Chinese Exclusion Act renewed for 10 more years.

1904

Chinese Exclusion Act made indefinite.

1905 Transnational Chinese boycott of U.S.-made products in China, Hawaii, and the United States.

1906 San Francisco earthquake destroys municipal and immigration records, creating covert opportunities for Chinese claims

to U.S. citizenship, resulting in increased immigration.

1910

Angel Island opens as official immigration station for Asian immigrants.

1911 China Republican Revolution ends Qing Dynasty Rule.

1922 Cable Act provides that any United States female citizen who marries an alien ineligible for citizenship forfeits her own

citizenship.

1924

National Origins Act closes immigration from all Asian Countries, including family members of United States citizens of

Asian descent.

1941

Pearl Harbor Attack brings United States and China into military alliance against Japan.

1943 Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act passed; institutes quota of 105 Chinese immigrants per year, right of naturalization

citizenship granted to Chinese immigrants.

1947

War Brides Act amendment allows thousands of Chinese American U.S. servicemen to bring wives and children to U.S.

from China.

Sources: Chan (1991); Takaki (1998); Hsu (2000); Chang (2003); Lee (2005).

Note: For additional listing of California laws, court rulings, and events, see Baxter, this volume: Table 1.

and Enping counties. The majority of Siyi immigrants originated in Taishan, a county about the

size of Rhode Island, so much so that historian

Madeline Hsu (2000) suggests that most 19thcentury Chinese in the U.S. are more properly

Main Body-42(3).indd 7

referred to as Overseas Taishanese or Taishanese

Americans. Although historians estimates vary,

somewhere between 10 to 20% of 19th-century

Chinese immigrants to the U.S. and Hawaii

originated in the Sanyi (Sam Yap) districts,

2/7/08 2:35:21 PM

FIGURE 1. Map of China, showing Guangdong Province.

(Drawing by Stella DOro.)

HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 42(3)

comprised of Panyu, Nanhai, and Shunde counties. A third, smaller group of immigrants came

from Zhongshang (also Xianshan or Heungshan)

county, south of Guangzhou. People from the

Siyi, Sanyi, and Zhongshang regions spoke mutually unintelligible Cantonese dialects, so that

members of the Chinese immigrant population in

the U.S. and Hawaii were linguistically diverse.

Additionally, the region was co-occupied by several ethnic groups, the most numerous of which

were Punti and Hakka. Most of those traveling

to the U.S. mainland were members of the Punti

ethnic group, while immigrants to the Kingdom

of Hawaii were primarily Hakka (Chan 1991;

Takaki 1998:3; Dehua 1999; Pan 1999; Hsu

2000; U.S. Department of State 2004).

Mass population movements are often characterized as the product of a push-pull

dynamic: immigrants are spurred to leave their

FIGURE 2. Map of Guangzhou region showing Siyi (Sze Yup) and Sanyi (Sam Yap) districts and Zhongshan County.

(Adapted from Hsu 2000:xxii [Map 1] and Pan 1999:34 [Map 1.9]; drawing by Stella DOro.)

Main Body-42(3).indd 8

2/7/08 2:35:22 PM

BARBARA L. VOSS AND REBECCA ALLENOverseas Chinese Archaeology

homelands in response to poverty, political and

religious persecution, or other unpleasant conditions, and they are drawn to new lands by

the promise of economic opportunities and a

desire for adventure and worldliness. Nineteenthcentury Chinese immigration was no exception.

The stability of the Qing dynasty (16441911)

was challenged by both foreign intervention

and internal strife. Guangdong was a stronghold

of internal resistance to the Qing dynasty and,

as such, had been subject to punitive taxation

regimes and heightened state surveillance. The

province was also deeply affected by the British Opium Wars (18391842, 18561860) and

by civil wars, including the Taiping Rebellion

(18511864) and the Punti-Hakka Clan Wars

(18551867). These violent upheavals were

accompanied by financial crises and floods that

contributed to poverty among rural residents.

While immigration was spurred in part by

poverty and war, it was the regions relative

prosperity that allowed its residents to travel

to other lands. Nineteenth-century Guangzhou

included a thriving class of skilled craftsworkers,

merchants, and professionals whose entrepreneurial skills were honed in Cantons international

trade markets. It was their transnational connections and financial resources that enabled mass

emigration from the region (Chen 2000; Liu

2002). Emigration brokerages became important

businesses in Guangzhou, not only facilitating

the immigrants initial journeys abroad but also

transmitting mail, remittances, and news between

immigrants and their families. This connection

allowed Chinese living overseas to remain in

touch with life in China and participate in the

community from afar (Takaki 1998:3142; Hsu

2000:1718; Chang 2003:119,3033).

The pull that drew 19th-century Chinese

immigrants to new lands varied throughout the

globe and changed over time. In the U.S. mainland, the first wave of Chinese immigration was

prompted by news of the 1848 discovery of gold

at Sutters Mill in California. Prior to 1849, no

more than 50 Chinese (mostly scholars, merchants, former sailors, and performers) lived in

the continental U.S., most in urban port cities in

the North Atlantic (Chang 2003:26,103). About

30 to 40 lived in the Kingdom of Hawaii

during the same time, working primarily in

trade and sugar production (Lai 1999:261). In

the first four years of the Gold Rush, Chinese

Main Body-42(3).indd 9

immigration to the U.S. mainland shifted to the

Pacific Coast and increased exponentially: in

1849, 325 Chinese immigrants landed in San

Francisco; 450 came in 1850; 2,716 arrived in

1851; and in 1852, an astounding 20,026 Chinese passed through the Golden Gate (Takaki

1998:79). This decade also witnessed the first

major wave of Chinese immigration to the

Kingdom of Hawaii. Seeking to end their reliance on native Hawaiian labor, a consortium of

American planters founded the Royal Hawaiian

Agricultural Society in 1850 in order to recruit

Chinese laborers to the islands. The first group

of 195 contract laborers arrived in Hawaii in

1852 (Chan 1991; Takaki 1998:2426; KrausFriedberg, this volume).

In both the U.S. mainland and Kingdom of

Hawaii, Chinese immigrants arrived as part of

a large wave of immigration from European and

Asian countries. Some historical accounts have

characterized Chinese immigrants as sojourners, interested only in making money and then

returning to their home country, in contrast to

European immigrant settlers who planned to

make the United States their permanent home

(Siu 1952). Certainly, the lure of quick riches

was an inducement used by brokers and labor

recruiters in Guangzhou, promising young men

that they could quickly earn a lifetimes wages

in a few short years and return to China as

rich and powerful men. Recent scholarship on

immigration return rates in the continental U.S.

reveals the sojourner vs. settler distinction to

be false. About 48% of 19th-century Chinese

immigrants returned to China to live (Yang

1999:62); for English immigrants, the return

rate was 55%; Scotch, 46%; Irish, 42%; Polish,

40%; Italians, 50%; Greeks, 46%; Japanese,

55% (Takaki 1998:11). Clearly, many immigrants

from both European and Asian nations came to

the U.S. with the intention of returning to their

homelands. Some who had intended to settle

may have been disillusioned and decided not

to stay. Still others who might have planned

a short sojourn became permanent residents,

through either inclination or inability to return.

Both European and Asian immigrants maintained

strong cultural, political, and economic ties with

their home countries. In these respects, Chinese

immigrants were typical of the larger pattern of

19th-century U.S. immigration.

2/7/08 2:35:23 PM

10

Despite these similarities, Chinese immigrants

experienced their arrival and tenure in the U.S.

mainland very differently from European immigrants. Long before the advent of large-scale

immigration, Chinese goods and people were

marketed and displayed in the U.S. as exotic

yet dangerous curiosities (Tchen 1999). Upon

disembarking in U.S. ports, Chinese immigrants

faced racist stereotypes and discriminatory laws

and court rulings that denied them the legal

standing and economic opportunities accorded to

most European immigrants. The 1790 Naturalization Law barred non-white immigrants from

applying for U.S. citizenship. While European

immigrants were viewed as potential citizens

of the country, Chinese and other non-white

immigrants were perpetual foreigners. As

Chinese immigration accelerated in the 1850s,

some state legislatures, especially Californias,

passed new laws that disproportionately affected

Chinese immigrants. These laws levied punitive

taxes, restricted immigration of family members,

and barred Chinese from owning land and from

working in certain industries. Court decisions,

most notably the 1852 California Supreme Court

decision of People v. Hall, affirmed Chinese

legal status as non-white, so that, for example,

Chinese testimony could not be admitted in

cases against white defendants. This allowed

anti-Chinese racism to escalate into large-scale

violence. Scott Baxter (this volume) discusses

documentary and archaeological evidence of

Chinese resistance against discrimination and

racist violence. Chinese responses to persecution included not only legal measures but also

material strategies that included fortifying Chinatowns, constructing fire-fighting infrastructure,

and acquiring weapons to defend themselves and

their communities.

While there was a general and persistent pattern of racial discrimination against people of

Chinese descent in both federal and local laws,

the legal status of Chinese immigrants varied

among states and between the U.S. and Hawaii.

Pacific Coast states generally had the most

restrictive and punitive laws. In much of New

England and the South, for example, antimiscegenation laws did not target people of Asian

descent, and many Chinese immigrants in those

regions intermarried with non-Chinese (Chang

2003:110113). Even within the U.S., archaeologists must be cautious not to overgeneralize the

Main Body-42(3).indd 10

HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 42(3)

experience of one Chinese immigrant community

as representative of the Chinese immigration

experience as a whole.

Nineteenth-Century Labor, Economy,

and the Anti-Chinese Movement

Chinese participation in the U.S. economy

changed throughout the middle- and late-19th

centuries. As the economy cycled, so too did

reactions to the Chinese presence in many U.S.

communities (Figure 3). Through the 1850s, most

Overseas Chinese worked as independent prospectors or in small mining consortiums, or in service

and mercantile businesses catering to miners. In

the 1860s, as the returns from placer mining

diminished, some shifted to wage employment

in quartz (hard-rock) mines and in mining operations in other U.S. states and western territories.

Many Chinese immigrants were recruited to work

in railroad construction, where they comprised as

much as 90% of the workforce (Takaki 1998:85).

FIGURE 3. Advertisement from San Joses Daily Mercury

newspaper, 22 May 1887.

2/7/08 2:35:24 PM

BARBARA L. VOSS AND REBECCA ALLENOverseas Chinese Archaeology

It was also during the 1860s that Chinese immigrant neighborhoods (Chinatowns) began to form

in most major western cities in the U.S. and in

some North Atlantic cities, primarily Boston and

New York.

The 1870 census listed 63,199 Chinese living

in the U.S. mainland. Although most (78%)

still resided in California, increasing numbers

lived in other states (Fosha and Leatherman,

this volume:Fig. 2). Chinese workers rapidly

achieved a prominent role in agriculture as

mining and railroad employment decreased. In

1870, 1 in 10 farm workers in California were

Chinese; by 1884, they comprised 50% of the

agricultural workforce, and by 1886, almost

90% (Chan 1986; Chang 2003:72). Most Chinese were legally classified as aliens ineligible

for citizenship and consequently were barred

from owning land. As a result, most Chinese

became tenant farmers or developed agricultural

partnerships with non-Chinese farmers, although

a few U.S.-born Chinese did manage to acquire

landholdings. Chinese agricultural workers

were also recruited by planters in the South to

replace emancipated African Americans; after

fulfilling their labor contracts, most Chinese

in the South left the fields to establish retail

and grocery businesses in New Orleans and in

smaller towns and cities, where they catered

largely to an African American clientele (Chang

2003:9399,166167). Along the Pacific Coast,

Chinese entrepreneurs established ocean-side

camps to harvest and process seafood products

for markets in both the U.S. and China (Lydon

1985; Collins 1987; Greenwood and Slawson,

this volume). Others pursued mining in the U.S.

territories that became Nevada, Idaho, Montana,

and Colorado (Hardesty 1988; Valentine 2002).

Many Chinese found employment in major

urban industries in California, the Pacific Northwest, the North Atlantic states, and in major

Midwestern industrial cities such as Chicago.

They figured especially prominently in shoe

and boot manufacture, woolen mills, tobaccoprocessing and cigar manufacture, the garment

industry, cutlery manufacture, fruit and vegetable

canneries, and fish processing (Rhoads 1999;

Chang 2003:7277,100102). It was also during

the 1870s that Chinese-owned businesses began

to proliferate. While laundries were the most

visible and widespread, Chinese-owned businesses included factories, retail establishments,

Main Body-42(3).indd 11

11

restaurants, stores, and medical and law offices.

Increasing numbers of Chinese men entered

domestic service during this period (Siu 1987;

Chan 1991:3335; Okihiro 2001:7678; Chang

2003:4849).

The 1870s were simultaneously an era of

increased anti-Chinese sentiment in the U.S.

mainland. The completion of the transcontinental

railroad, which released thousands of Chinese

immigrants to work in agriculture and industry,

coincided with the end of the Civil War. More

than 3 million former Union and Confederate

soldiers were now re-entering the labor force

along with emancipated African Americans

(Chang 2003:117). The result was a nationwide

economic depression with pervasive unemployment and competition for jobs, followed by a

stock market collapse in 1877. While anti-Chinese legislation and violence had occurred since

1852, in the 1870s Chinese immigrants were

increasingly blamed for the nations economic

woes and subjected to discriminatory legislation and taxation, harassment and arson, and

pogroms (Chan 1991:4649). Contrary to their

image as passive and docile workers, Chinese

laborers organized, held strikes, and pursued

legal remedies against exploitative working conditions, at times building coalitions with white

labor unions (Chan 1991:8183; Takaki 1998;

Rhoads 1999; Chang 2003; Baxter, this volume).

With the collapse of the U.S. economy, Chinese

laborers were easy scapegoats. Political rhetoric

coalescing around The Chinese Must Go!

served to mask underlying antagonisms among

whitesbetween white capitalists and white

workers and between U.S.-born and foreign-born

whites (Saxton 1971).

In the early 1880s, intensified racial violence and anti-Chinese rhetoric culminated in

two eventsthe Chinese Exclusion Act and

the Driving Outthat profoundly shaped

the demography, economy, and geography of

Chinese America into the late-20th century. In

1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act prohibited further immigration of Chinese laborers to the U.S.

mainland and also prohibited Chinese laborers

already living in the U.S. from sponsoring the

immigration of their wives and children (Gyory

1998; Wong and Chan 1998). Subsequent

amendments and extensions restricted Chinese

immigrants travel between the U.S. and China

(Table 1). From 1892 onward, Chinese residents

2/7/08 2:35:24 PM

12

of the United States had to carry certificates of

legal residence on their persons at all times,

without which they were subject to summary

deportation (Chan 1991:5455).

Following the passage of these restrictions

on new immigrants, anti-Chinese coalitions

undertook violent campaigns to expel existing

Chinese immigrants from the nation. Known

as the Driving Out, this epoch of terror was

a period when few Chinese were safe from

racial violence. Anti-Chinese rallies frequently

escalated into pogroms, lynchings, and arson,

among the most notorious of which were the

massacres in Rock Springs, Wyoming (1885),

and Snake River, Oregon (1887) (Chan 1991:49;

Takaki 1998:92). Anti-Chinese violence continued throughout the mid-1880s and into the

early 1890s in many parts of the American

West, terrorizing dozens of Chinese communities

throughout California, Idaho, Colorado, Oregon,

and Washington. Anti-Chinese campaigns followed regular patterns, often beginning with

the maiming or murder of one or more Chinese

individuals, then pogroms and arson against Chinatowns and Chinese neighborhoods, culminating

in expulsion drives to eliminate Chinese from

the targeted region (Chan 1991:4851).

After 1882, the number of Chinese in the

United States mainland steadily declined, from

105,465 in 1880 to 89,863 in 1900 and 61,639

in 1920 (Takaki 1998:111112). Immigration

from China was now limited to a small number

of merchants and professionals. News of antiChinese violence was widely distributed in

China, and many prospective immigrants eligible

for U.S. entry chose to settle elsewhere, especially Canada or Mexico, which also became

routes for covert immigration into the U.S.

(Chang 2003:144; Lee 2005). In the face of

racist violence and economic discrimination,

many Chinese left the U.S. permanently. Those

who did remain became increasingly urbanized.

Between 1882 and 1920, once-thriving Chinese

communities in the interior West, Midwest, and

southern U.S. diminished or disappeared. Many

Chinese Americans relocated to major Pacific

Coast cities and to New York and Boston

(Takaki 1998:240; Smits, this volume). As de

jure and de facto racial segregation increased in

both housing and employment, Chinese Americans increasingly worked in what Ronald Takaki

(1998:240) has termed the Chinese ethnic

Main Body-42(3).indd 12

HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 42(3)

economy, a service-based economy dominated

by Chinese-owned laundries, restaurants, retail

stores, herbal medicine shops, fisheries, and

craft workshops.

These conditions continued until World War

II when the Chinese Exclusion Act was finally

repealed, and the War Brides Act facilitated

family reunification for thousands of U.S. servicemen of Chinese American descent (Zhao

2002). Quotas for new Chinese immigration

remained exceedingly small (105 persons per

year). It was not until 1965 that the federal

Immigration Act repealed racial restrictions on

immigration to the United States and ushered

in what is known as the second wave of Asian

immigration. As of 2002, more than 12.5 million

people of Asian descent lived in the U.S., comprising 4.4% of the population. Chinese Americans and Chinese immigrants are the largest

national group within this diverse population

and are estimated to comprise 25% to 30% of

all Asian Americans (Barnes and Bennett 2002;

Reeves and Bennett 2003).

Cohesion and Diversity

The population of 19th-century Chinese immigrants to the United States and the Kingdom

of Hawaii was multifaceted and internally

diverse. Chinese immigrants arrived from different districts, counties, and villages and

spoke a range of distinct dialects. They came

with varying degrees of education, professional

training, and economic resources. Many were

young teenagers, thrust into adult responsibilities; others in their 20s, 30s, and 40s brought

decades of professional and life experience.

Those recruited as contract laborers or under

the credit-ticket system began this new phase

of their lives under the burden of considerable

debt. Those able to finance their own journeys

had greater latitude in their employment and

place of residence. Within Chinese communities, relationships between landlords and tenants,

labor contractors and workers, lenders and debtors, and merchants and customers were shaped

by mutual necessity and antagonistic interests.

While aiding their fellow immigrants in finding

work, lodging, and goods, some Chinese business owners also gained a measure of control

and dominance within Overseas Chinese communities (Chan 1991:66).

2/7/08 2:35:25 PM

BARBARA L. VOSS AND REBECCA ALLENOverseas Chinese Archaeology

In the mainland and Hawaii, Chinese immigrants formed new associations through reference

to old-country bonds and new-world conditions.

These included business consortiums, tongs

(secret societies), fongs (family and village

clans), huiguan (district associations), occupational guilds, temple associations, musical and

artistic groups, and festival organizing committees

(Chan 1991:6367; Yu 2002; Lai 2004). Funerary

associations cared for the bodies and spirits of

the deceased (Chung and Wegars 2005; Fosha

and Leatherman, this volume; Kraus-Friedberg,

this volume; Smits, this volume). A particularly

important moment in Chinese American history

occurred in 1862, when several district associations formed a federation called the Zhonghua

Huiguan (Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association), often referred to by European Americans

as the Six Chinese Companies (Chan 1991:65;

Baxter, this volume). In addition to these formal

organizations, restaurants, stores, and gambling

halls provided venues for more informal socializing, camaraderie, and recreation (Costello et

al., this volume).

In the mainland, and to a lesser extent in

Hawaii, Chinese immigrant communities were

overwhelmingly composed of men. In the 1850s

to 1860s, this gendered immigration pattern

was typical of most immigrant groups going

to the American West: during this period, men

comprised 92% of Californias nonindigenous

population (Chang 2003:35). While this was

a temporary situation for most European and

European American men, short-term absences

from their kin became permanent separations

for Chinese immigrants. After the passage of

racially specific immigration laws, Chinese

family reunification became increasingly difficult, and for some men, impossible. As a

result, most U.S. mainland Chinese communities

had an extreme gender imbalance far into the

20th century. Nationally, in 1870, there were

14 Chinese men for every Chinese woman. By

1890, the imbalance had increased to 28 Chinese men for every Chinese woman. Throughout

the 19th- and early-20th centuries, the number

of Chinese women in the U.S. mainland never

exceeded 5,000 (Yung 1995). The situation was

less extreme in the Kingdom (and later, Territory) of Hawaii, where nearly one in eight

Chinese immigrants were women.

Main Body-42(3).indd 13

13

The initial reasons for male-dominated immigration were multifaceted. Among rural families

in southern China, women played an important

role in the agricultural economy and in care of

family elders. Their labor and expertise were

necessary to sustain their families while their

husbands, fathers, and sons established new

lives in the United States or Hawaii (Mazumdar

2003). By traveling alone, men also minimized

transportation costs and were able to seize

employment opportunities without concern for

their wives and childrens comfort and safety.

U.S. and Hawaiian employers preferred an allmale labor force, unencumbered by dependants,

and instructed labor recruiters in Guangzhou

accordingly. The 1875 Page Act and the 1882

Chinese Exclusion Act and its amendments shut

the door on family reunification for all but the

most prosperous Chinese immigrants. While

Overseas Chinese in most other countries were

increasingly sponsoring the immigration of their

wives and children, Chinese communities in the

U.S. mainland remained primarily bachelor

communities (Peffer 1999), although some

communities had many Chinese families (Yu

2001). Some Chinese men married non-Chinese

women, especially in New York City, the U.S.

Southwest, and the Kingdom of Hawaii. This

was prohibited in many other states by antimiscegenation laws. After 1922, an American

woman who married a Chinese immigrant forfeited her U.S. citizenship (Takaki 1998:3638;

Peffer 1999).

A flexible understanding of what family

meant enabled the endurance and reproduction

of Chinese families through long-term separations. From 1890 to 1940, about two-fifths of

Chinese American men were married but lived

apart from their wives and children. These bicontinental split households were common in

Taishan and other qiaoxiang (sojourners villages), with husbands and sons earning wages

in the U.S. to support their wives, children,

and parents in Guangdong (Pan 1999:27; Hsu

2000:91100). Fathers and uncles living abroad

encouraged their Chinese-born sons and nephews

to join them in the U.S., leading to multigenerational chains of immigration within families.

By the mid-20th century, some Chinese families

had lived and worked in the U.S. for three or

more generations, but all of the family members

2/7/08 2:35:25 PM

14

were still Chinese born (Keong 1999:77; Pan

1999:17; Greenwood, this volume).

The predominantly male composition of Chinese immigrant communities in the U.S. draws

attention to the importance of gender and sexuality as constitutive aspects of Chinese American

subjectivity during the late-19th and early-20th

centuries (Ting 1995; Yung 1995; Hsu 2000;

Leong 2000; Williams, this volume). Chinese

men forged new forms of households (Van

Bueren, this volume) and alternative kinship

relationships, such as those between sponsors

and their paper sons (Ting 1995:267277).

Extra-familial associations such as clan groups,

district associations, guilds, and business partnerships took on increased importance (Chan

1991:6367; Lai 2004; Voss, this volume). It

was common for an individual to belong to as

many organizations as possible: Indeed, it is

the overlapping and interlocking memberships of

so many associations that make possible what is

often called Chinatown politics, where Chinese

community leaders are typically those who hold

leadership positions in several interlocking and

leading organizations (Wickberg 1999:83).

HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 42(3)

In both historical and archaeological accounts,

Chinatown stores emerge as uniquely Chinese

American social institutions (Yu 2001; Allen et

al. 2002:8183). Merchants were able to sponsor their wives and childrens immigration, and

these family-run stores combined consumerism

with the social functions of extended kinship

(Figure 4). Besides selling Chinese goods, stores

were places to obtain an inexpensive meal,

drink tea and exchange gossip, tell folktales and

stories, and send and receive mail. Merchants

children were doted on by countless uncles

who patronized the stores with regularity. Stores

were sites of political activity, both domestic

and transnational, and places where immigrants

could connect with labor contractors, translators, lawyers, and business partners (Takaki

1998:127130; Yu 2001:22). Other Chinatown

institutions were temples, theaters, restaurants,

and living quartersthe configuration and

architecture of which varied from community

to community.

The gender imbalance had profound effects

on Chinese women, both those who immigrated

and those who remained in China. In the U.S.

FIGURE 4. Artist John Lytles interpretation of merchant scene along Dupont Street in the Woolen Mills Chinatown, San

Jose, based on archaeological findings and historic documents. Original painting on display at the Ng Shing Gung

Museum, Kelley Park, San Jose. (Courtesy of John Lytle.)

Main Body-42(3).indd 14

2/7/08 2:35:25 PM

BARBARA L. VOSS AND REBECCA ALLENOverseas Chinese Archaeology

mainland, Chinese women were stereotyped as

prostitutes (Hirata 1979; Yu 1989; Peffer 1999).

There were many Chinese women who worked

in this then-legal profession, often having been

recruited through deception and bound to years

of service through coercive labor contracts and

fear of violent reprisals (Hirata 1979; Takaki

1998:122; Chang 2003:8389). Historians are

in general agreement that census records listing

as many as 60% of Chinese immigrant women

as prostitutes are grossly inflated as a result

of stereotypes and willful misunderstandings of

Chinese immigrant residential patterns (Coolidge

1909; Yung 1995; Takaki 1998:121123; Peffer

1999:711; Shah 2001:8285; Chen 2002).

Most Chinese women immigrated as the wives

of merchants and professionals, working as

housekeepers and partners in their husbands

businesses. In Hawaii, Chinese women also

immigrated as contract agricultural laborers,

often working alongside their husbands in the

cane fields. Archival research, memoirs, and

oral histories indicate that many 19th-century

Chinese immigrant women felt their lives to be

tightly circumscribed, as women were subject

to patriarchal control at home and anti-Chinese

violence in public. Despite racism and social

constraints on womens activities, Chinese immigrant women still took an active role in the

formation of Chinese American communities.

They advocated for changes in gender relations

through participation in womens movements in

both China and the U.S. (Tsuchida et al. 1982;

Yu 1989; Yung 1995, 1999; Ling 1998; Chang

2003:8991).

The other women involved in Chinese immigration were the Gold Mountain wives who

continued to live in Guangdong. Folksongs and

memoirs from that time recall the loneliness and

frustration many women felt in being unable

to join their husbands (Mazumdar 1989:56).

Remittances from mens labor in the U.S. and

Hawaii transformed the regions economy, as

immigrants not only sent money to their families

but also sponsored charitable and public works

such as schools, orphanages, hospitals, assembly halls, roads, bridges, and railroads (Dehua

1999). Some women gained considerable power

and prestige through their control over the distribution of remittances from overseas family

members and achieved a measure of autonomy

as they undertook responsibilities for family

Main Body-42(3).indd 15

15

affairs that would have otherwise fallen to their

husbands (Hsu 2000; Chang 2003:6671).

Despite severe limitations on family reunification, a population of American-born Chinese children slowly emerged. In 1876, the

Six Chinese Companies estimated that already

perhaps 1,000 Chinese children had been born

in America (Chang 2003:92). Their place of

birth entitled them to U.S. citizenship, but this

did not guarantee the full rights accorded to

most European Americans. Even American-born

Chinese were continually perceived as perpetual foreigners in their own country (Chan

1991:187; Takaki 1998; Chang 2003:174178).

New Directions in Chinese

American Historiography

The history of Chinese immigration and Chinese American communities has come a long

way since the German geographer Friedrich

Ratzel (1876) wrote the first historical account

of Chinese immigration to the United States.

Ratzel and most other accounts in the late-19th

and early-20th centuries were written from European and European American perspectives and

were generally framed through what was commonly called the Chinese question with regard

to race, labor, and immigration policy (Gibson

1877; Coolidge 1909; Sandmeyer 1939; Barth

1964). The tenor of historiography changed

in the 1960s as the result of four key events:

(1) the advent of the Civil Rights Movement

and the concomitant 1964 passage of the Civil

Rights Act, (2) the 1963 incorporation of the

Chinese Historical Society of America, (3) the

rise of a new social history paradigm, and (4)

the formation of the first Asian American studies

programs as a result of the 19681969 student

strikes at San Francisco State and University

of California, Berkeley (Umemoto 1989; Louie

and Omatsu 2001). New scholarship during this

period continued to wrestle with conventional

topics of labor, immigration, and economy but

was generally more careful to question the

stereotypes and racialized portrayals of Chinese

in archival sources (Lee 1960; Saxton 1971;

Lyman 1974).

It was also during the 1960s and 1970s that

a new generation of Chinese American scholars and activists began to write histories that

explicitly challenged the racial caricatures that

2/7/08 2:35:26 PM

16

pervaded earlier popular accounts and historical

works. One of the first such publications was

Thomas Chinn, Him Lai, and Phillip Choys

History of the Chinese in California (1969).

Intended to be used as a syllabus, this book

was published through sponsorship of the

Chinese Historical Society of America, initiating a continuing partnership among historians,

archaeologists, and national and local Chinese

historical societies. These and other Chinese

American historians expanded traditional archival sources (newspaper, court transcripts, etc.)

to include family histories, oral histories, and

privately owned photographs and documents.

These researchers also championed the importance of Chinese-language sources in the U.S.

and China, finding that there are significant

variances between English-language portrayals of

Chinese immigrants and their self-representations

in Chinese (Lai 1986; Chan et al. 1991; Yin

2000; Chen 2002; Yung and Lai 2003; Yung

et al. 2006). The expansion of source materials has had an especially salutary effect on

the historiography of Chinese immigrant and

Chinese American women, who were systematically underrepresented and misrepresented in

most official English-language records (Asian

Women United of California 1989; Yu 1989;

Yung 1995, 1999; Kim et al. 1997; Yu 2001;

Hune and Nomura 2003).

In the past two decades, the historiography

of Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans

has diversified, with an increasing number of

works presenting in-depth treatments of specialized subjects. In particular there has been an

avalanche of books and articles on U.S.-based

Chinese communities during the exclusion era

(18821943) (Gyory 1998; Wong and Chan

1998; Hsu 2000; Lee 2003; Chan 2005). While

studies of California, the Pacific Coast, and

Hawaii still dominate the literature (and this

volume is no exception), there is an increasing

effort to expand Chinese American historiography into other regions (Sumida 1998), most

notably New York (Tchen 1999; Wang 2001),

North Atlantic industrial cities (Rhoads 1999),

Chicago (McKeown 2001), the South (Cohen

1984), and the interior West (Wegars 1993,

2000, 2003; Zhu and Fosha 2004; Fosha and

Leatherman, this volume) as well as Canada

(Lee 2005) and Latin America (Hu-DeHart

1991; McKeown 2001; Yun and Laremont 2001;

Main Body-42(3).indd 16

HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 42(3)

Lee 2005). Since the 1990s some historians

have increasingly reframed Chinese American

history within a comparative approach, one that

examines the shared experiences of Chinese

Americans and other Asian immigrant groups

(Chan 1991; Takaki 1998) and the interrelationships among Asian American and other American ethnic and racial groups (Almaguer 1994;

Prashad 2000, 2001, 2006; Wang 2001; Yun

and Laremont 2001; Aarim-Heriot 2003; Maira

and Shihade 2006). Increasingly new historical

works interrogate the interconnected relationships

among racialization and gender and sexuality

(Tsuchida et al. 1982; Asian Women United of

California 1989; Ting 1995, 1998; Yung 1995,

1999). Nayan Shahs (2001) investigation of the

interplay between medical models of hygiene

and the racialization of Chinese populations

will be of particular interest to archaeologists

because of its attention to architecture, space,

and material culture.

At present, the most prominent controversy

in Chinese American historiography concerns

the degree to which Chinese immigration to

the U.S. mainland and Hawaii is an American

story or an Overseas Chinese story (Kim

and Lowe 1997). In the first instance, a growing body of scholarship specifically highlights

Chinese Americans and people of Asian history,

in general, with the formation and the development of the U.S. This research has challenged

the presumption that the U.S. is essentially a

European country, drawing attention to the

many ways in which the U.S. economy, government institutions, foreign policy, and national

culture were forged through centuries of intercontinental flows of people, goods, and ideas

between North America and Asia (Okihiro 1994,

2001; Lowe 1996; Takaki 1998; Palumbo-Liu

1999; Chen 2000; Lee 2003). Others view the

Chinese in the U.S. as members of an Overseas

Chinese diaspora that today numbers more than

36 million strong (Pan 1990, 1999; Ong 1999;

Chang 2003).

Increasingly, historians are negotiating this

tension by working within a transnational paradigm, one that investigates the unique aspects

of Chinese history in the U.S. while simultaneously recognizing the impact of out-migration on

China itself and tracing the webs that maintain

connections among people of Chinese heritage

throughout the world (Hu-DeHart 1999, 2005;

2/7/08 2:35:26 PM

BARBARA L. VOSS AND REBECCA ALLENOverseas Chinese Archaeology

Pan 1999; Chen 2000; Hsu 2000; Chuh and

Shimakawa 2001; McKeown 2001; Lee 2003,

2005; Mazumdar 2003; Louie 2004; Lee and

Shibusawa 2005; Chan 2005). The transnational

paradigm demands multistranded, multilingual,

multisited research designs and methodologies that can interrogate the tension between

transnational flows and specific sites (Chin et

al. 2000:279). With few historical archaeologists trained in Chinese languages and history

and little or no historical archaeology being

conducted in Guangdong, the challenges in the

development of a transnational archaeology of

Overseas Chinese communities are formidable.

Nonetheless, some archaeologists are already

deploying the conceptual advantages of a transnational interpretive framework in their research

(Williams, Smits, Kraus-Friedburg, all in this

volume).

Assessing Overseas Chinese Archaeology

Archaeological Investigations

With rare exceptions, the archaeology of

Overseas Chinese communities has been largely

confined to the U.S. (including Hawaii), Australia, and New Zealand (Schulz and Allen,

this volume). The deposits and sites formed by

Chinese who immigrated to South Asia, Latin

America, Canada, the Caribbean, Africa, and

Europe have yet to be identified and excavated.

In the U.S., the archaeology of Overseas Chinese populations began in the late 1960s and

1970s, with pioneering studies that included the

excavation of Chinatowns in Ventura, California

(Greenwood 1976, 1980); Lovelock, Nevada

(Hattori et al. 1979); Idaho City, Idaho (Jones

et al. 1979); and Tucson, Arizona (Olsen 1978,

1983; Ayres 1984; Lister and Lister 1989). In

the early 1980s, two publications marked the

beginnings of a comparative perspective on the

archaeology of Overseas Chinese communities:

Robert Schuylers (1980) Archaeological Perspectives on Ethnicity in America and Randall

McGuires (1982) The Study of Ethnicity in

Historical Archaeology.

Research on Overseas Chinese sites slowly

increased through the 1980s, primarily through

cultural resource management projects that

encountered, rather than sought out, the material

remains of former Chinese communities. Two

Main Body-42(3).indd 17

17

examples of research in Sacramento, California,

during this decade illustrate departures from

this general trend. Adrian Praetzellis and Mary

Praetzelliss (M. Praetzellis and A. Praetzellis

1981, 1982, 1990; A. Praetzellis et al. 1987)

excavation and analysis work in the IJ56 Block

was guided by a research design centered on the

investigation of an historic Chinese merchant

community. David Felton and colleagues (1984)

investigation of the Woodland Opera House

site, near Sacramento, laid the foundation for

subsequent studies by identifying and defining

artifact types, usages, and chronologies. Also

in California, Clark Brotts (1982) research at

Weaverville contributed one of the first in-depth

studies of a Gold Rush era Chinese mining

community. In Nevada, Donald Hardestys

(1988) analysis of mining-related archaeological

sites and features was the first study to establish

a framework for the investigation of nonurban

Chinese communities. In addition to site reports,

many publications during this period focused

on establishing an empirical foundation for

archaeological analyses, including developing

artifact typologies and identifying chronologically diagnostic materials. The 1982 founding of

the Asian American Comparative Collection at

the University of Idaho was instrumental in the

standardization of archaeological nomenclature

(Wegars, this volume).

Beginning in the 1980s and accelerating in

the 1990s, Overseas Chinese archaeology has

grown exponentially. In the U.S. mainland, this

work has been driven primarily by urban redevelopment and other CRM programs. Robust,

multiphased research programs in California

have been conducted in five major metropolitan

areas: San Francisco (Pastron 1981); Sacramento

(Farris 1980; M. Praetzellis and A. Praetzellis

1981, 1982, 1990, 1997; Felton et al. 1984; A.

Praetzellis et al. 1987; A. Praetzellis and M.

Praetzellis 1998); Oakland (A. Praetzellis 2004;

M. Praetzellis 2004; Fong 2005; Naruta 2005);

Greater Los Angeles (Greenwood 1976, 1980,

1996; Great Basin Foundation for Anthropological Research 1987; Costello et al. 1998);

and San Jose (Allen et al. 2002; Allen and

Hylkema 2002; Baxter and Allen 2002; Voss et

al. 2003, 2005; Camp et al. 2004; Clevenger

2004; Williams 2004, this volume; Voss 2004,

2005, this volume; Michaels 2005; Baxter, this

volume). This research has enabled the emer-

2/7/08 2:35:27 PM

18

gence of broader comparative research designs

and regional perspectives that were simply not

possible only 20 years ago.

In contrast, investigations of the many small,

nonurban labor camps occupied by Chinese

laborers throughout the West are much fewer

in number. Chinese workers who were engaged

in mining, railroad construction, lumbering,

charcoal burning, and similar activities occupied

these sites. Archaeologists have used diverse

approaches in these studies. Richard Markleys

(1992) investigation of two Chinese mining sites

in Sierra County, California, focused on reconstructing past lifeways in camps and households.

A number of sites related to the construction of

the Virginia & Truckee Railroad were investigated in the Virginia Range, Nevada, and interpreted as Chinese-occupied railroad construction

camps (Wrobleski 1996; Rogers 1997). A substantial body of work has also been compiled

on the Chinese logging activities in the Tahoe

Basin area (Elston et al. 1981, 1982). Leslie

Hill (1987) has examined Chinese charcoalburner camps in the California/Nevada Carson

Range, focusing primarily on site classification

and Chinese acculturation. More notably, Susan

Lindstrm (1993) documented a Chinese cabin

site near Truckee, California, and brought into

question the sojourner model frequently applied

to Overseas Chinese. In this volume, studies by

Baxter, Roberta Greenwood and Dana Slawson,

and Thad Van Bueren expand the archaeology of

rural Chinese laborers and entrepreneurs.

Publishing Chinese Overseas Archaeology

While Overseas Chinese archaeological

research expanded widely during the last 15

years, published studies are still few in number,

with most research located in so-called gray

literature site reports, theses, dissertations, and

conference papers (Voss 2005; Schulz and Allen,

this volume). The 1980s and 1990s saw the

publication of two foundational monographs,

Down by the Station: Los Angeles Chinatown,

18801933 (Greenwood 1996) and Wong Ho

Leun: An American Chinatown (Great Basin

Foundation for Anthropological Research 1987),

and one edited volume, Hidden Heritage: Historical Archaeology of the Overseas Chinese

(Wegars 1993). Recently, two general publications in historical archaeology (Orser 2004; De

Main Body-42(3).indd 18

HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 42(3)

Cunzo and Jameson 2005) have included serious

considerations of Overseas Chinese archaeology,

the first since Schuylers and McGuires studies

in the early 1980s. Very little Overseas Chinese

research has been published in peer-reviewed

archaeological journals. In 39 years of publication, the journal Historical Archaeology has

published only 10 articles on Overseas Chinese

archaeology, 4 of which are studies of Chinese

coins. Northwest Anthropological Research Notes

has published five articles, including two bibliographies. Other journalsthe Pacific Coast

Archaeological Society Quarterly, the International Journal of Archaeology, Archaeology of

New Zealand, Archaeology, World Archaeology,

and Industrial Archeologyhave each published

only one or two articles. There have been no

articles on Overseas Chinese archaeology in

American Antiquity. The authors are aware of

only one article on Overseas Chinese archaeology published in a history journal (Maniery and

Costello 1986).

The underpublication of Overseas Chinese

archaeology is no trivial matter. It is challenging for archaeologists interested in the subject

to identify and access most archaeological studies of Overseas Chinese sites. This difficulty

is often insurmountable for historians, Asian

American studies scholars, and members of Chinese historical societies who are not accustomed

to navigating archaeologys ocean of gray literature. While no single publication can remedy

this situation, the authors and guest editors hope

that this journal issue and the included bibliography (Schulz and Allen, this volume) will serve

as an entry point for archaeologists, historians,

and others interested in the subject.

Current Challenges and Opportunities

In the U.S., Overseas Chinese archaeology faces three primary challenges that must

be surmounted if this research is to fulfill

its potential. The first challenge is that most

archaeological research on Overseas Chinese

communities, households, and businesses is still

largely descriptive and framed only within local

historical points of reference. Since standard

nomenclature and classification schemes have

been developed now for most types of Overseas

Chinese material culture, such descriptive studies

are no longer necessary, except in the case of

2/7/08 2:35:27 PM

BARBARA L. VOSS AND REBECCA ALLENOverseas Chinese Archaeology

unusual, understudied, or rare objectssuch as

the cache of Asian coins analyzed by Margie

Akin that is presented by Julia Costello and

colleagues in this volume.

Research on Overseas Chinese sites, deposits,

and assemblages needs to be conducted with

the same attention to problem-oriented research

designs that is accorded to other sites. Several

methodological issues also require attention. For

example, with rare exceptions (M. Praetzellis

2004; Greenwood and Slawson, this volume;

Van Bueren, this volume), Overseas Chinese

archaeology has tended to focus on Chinatowns,

which has reinforced the mistaken assumption

that Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans

were insular and self-segregating populations.

Most Chinese in the U.S. lived and worked in

multiethnic and multiracial settings. A pressing

need exists for research methodologies for the

archaeology of pluralistic, multiethnic sites and

settlements. Paul Mullins (this volume) particularly encourages archaeologists studying Overseas

Chinese communities to attend more directly to

issues of power and race across the color lines of

North American society. Mullins suggests that a

core methodological concern in Overseas Chinese

archaeology in North America is how to position

Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans in

relation to other Americans.

The second challenge is that, to date, the vast

majority of archaeological studies on Overseas

Chinese sites in the U.S. have adopted an acculturation research paradigm, and consequently

the objective of most archaeological studies has

been to determine the degree to which Chinese

immigrants assimilated into American culture.

The acculturation approach, critiqued elsewhere

at length by Barbara Voss (2005), is inherently

flawed because it precludes consideration of the

many ways in which Chinese immigrants and

Chinese Americans have themselves participated

in the formation of American national culture,

however conceptualized. The authors encourage

researchers studying Overseas Chinese sites to

consider other theoretical models of intercultural contact, including adaptation, creolization,

synergism, hybridity, and ethnogenesis, that can

account for complex and multifaceted interrelationships between Chinese and non-Chinese

as well as between immigrants and host communities. As discussed above, transnational

frameworks may be especially important in

Main Body-42(3).indd 19

19

tracing the complex economic, demographic, and

cultural webs that have bound Chinese and U.S.

communities together since the 1850s.

The third challenge to the continued development of Overseas Chinese archaeology is

orientalism. Broadly defined, orientalism can

be understood as a Western belief in a radical and essential difference between the East

and the West. It has deep historical roots, both

in popular culture and in academia, through

the constitution of the Orient or the East as a

distinct arena of knowledge production (Said

1979; Tchen 1999; Williams, this volume). One

danger of orientalism lies in its tendency to

use Asian and Arabic cultures as the other

through which the West is defined as rational,

civilized, advanced, and superior. For example,

Jean Phinney (1996) has observed that social

scientists generally assume that people of Asian

heritage place greater emphasis on maintaining

harmony in relationships, place group interests

over individual interests, and organize their lives

around fulfilling family obligations. In contrast,

people from Western backgrounds are assumed

to emphasize the individual over the group

and to construe the individual as independent,

autonomous, and self-contained. This oppositional binary, which is often summarized as a

contrast between tradition and modernity, has

no empirical validity: individualism and family

values are evident in both Asian-heritage and

European-heritage populations (Phinney 1996).

As Edward Said (1979:4546) explains, When

one uses categories like Oriental and Western

as both the starting and end points of analysis

the result is usually to polarize the distinctionthe Oriental becomes more Oriental, the

Westerner more Westernand limit the human

encounter between different cultures, traditions,

and societies.

In historical archaeology, the influence of orientalism can be observed along many registers.

Archaeological writing often exhibits a fascination with Chinese material culture as exotic

and describes artifacts in terms that emphasize

their aesthetic differences from Western material

culture. In practice, a Bamboo-pattern porcelain

rice bowl was as commonplace and utilitarian

an object in 19th-century Overseas Chinese

communities as a transfer-print ironstone plate

was in contemporary European American households. More seriously, archaeological reports

2/7/08 2:35:28 PM

20

and publications have disproportionately focused

on those aspects of Chinese community life

that were sensationalized in the 19th-century

media, such as opium consumption, gambling,

and prostitution (Fong 2006). In the authors

observations, it is also still far too common that

archaeological reports and publications reference and reproduce ethnic slurs and stereotyped

portrayals of Chinese immigrants and Chinese

Americans. Stereotypes need not be negative

to be damaging. Archaeologists who interpret

archaeological evidence through reference to a

set of generalized, so-called Chinese cultural

values or assert that Chinese immigrants and

Chinese Americans were universally hard working, industrious, thrifty, enterprising, or entrepreneurial dehumanize the people they study

and erase the variability in abilities, aptitudes,

personalities, and life histories within Overseas

Chinese communities.

Addressing orientalism requires not only that

archaeologists be self-reflexive about personal

beliefs and attitudes but also that archaeology

re-examine the underlying structures of research

programs. One core aspect of orientalism is

the study of the East by the West for the

Wests own purposes. Historically such scholarship arose to support the U.S. and European

governments in their management of colonial

holdings and in the expansion of industrial

capitalism (Said 1979). Today, as historical

archaeology increasingly includes the study of

Asian immigrant and Asian American communities within its purview, it is worth asking

who benefits from such research and how this

research is being used.

The greatest opportunity in Overseas Chinese

research is the potential for the development

of collaborative research structures that reach

beyond national and disciplinary boundaries.

To some extent, this work is already occurring.

Most articles in this thematic issue present

research that has developed in collaboration

among archaeologists, historians, Chinese historical societies, and present-day Chinese-descendant

and Chinese-immigrant communities. A case in

point is the authors and guest editors ongoing

relationship with Chinese Historical and Cultural

Project (CHCP), a heritage organization in San

Jose, California, that has more than 20 years

experience working with archaeologists and

museums to present and interpret Chinese heri-

Main Body-42(3).indd 20

HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 42(3)

tage (Figures 5 and 6). There is no question that

research designs, analysis methods, and interpretations of Overseas Chinese sites and collections

have been fundamentally transformed through

this sustained collaboration, which has opened

up new topics for archaeological investigation

that have rarely been addressed in past studies

(Allen et al. 2002:42,43,211212; Voss 2005).

In her commentary on the articles in this issue,

Connie Young Yu (this volume) draws careful

attention to points where a greater understanding

of Chinese history and cultural practices could

transform archaeological interpretation, and she

also notes the value of archaeological research

towards expanding the scope of historical understandings of Chinese immigrant populations.

While collaboration between archaeologists and

local heritage communities is a good beginning,

it would be an insufficient ending. Historical

archaeologists studying Overseas Chinese assemblages need to engage not only with each other

but also with their colleagues in history and in

Asian American and Asian studies; further, Overseas Chinese archaeology must embrace the transnational and regional as well as the local. The

research presented in this thematic issue is one

small step towards realizing that vision, and there

are other encouraging signs. In 1995, the Chinese

Heritage Centre was founded in Singapore to

promote the global study of Overseas Chinese

communities, and it launched the Journal of Chinese Overseas in 2005 as an international forum

for dissemination of such research. In 1999, the

Chinese Historical Society of Greater San Diego

and Baja California hosted the Sixth Chinese

American conference, resulting in the publication of an edited volume that includes historical,

biographical, and archaeological studies (Cassel

2002). In 2001, National Taiwan University and

Australian National University co-published the

proceedings of an interdisciplinary conference

on Overseas Chinese communities (Chan et al.

2001). In 2006, The Society of Historical Archaeology Annual Meeting included a symposium

on Overseas Chinese Archaeology that involved

researchers from Australia and New Zealand as

well as the United States. Increasingly, graduate

students studying Overseas Chinese archaeology are including Chinese language study and

research in China as part of their training.

The prospects for multiscalar, multisited, and

multidisciplinary research are strong. Archaeology

2/7/08 2:35:28 PM

BARBARA L. VOSS AND REBECCA ALLENOverseas Chinese Archaeology

21

FIGURE 5. Members of the Chinese Historical and Cultural Project and Stanford University meeting at the Stanford

Archaeology Centers open house: (left to right) Anita Kwock, Barb Voss, Gina Michaels, Lillian Gong-Guy, Ezra Erb, and

Ken Jue. (Photo taken 8 February 2003, reprinted courtesy of Market Street Chinatown Archaeological Project.)

FIGURE 6. Historian Connie Young Yu (front, center) regularly lectures on Chinese American history to students involved

in the Market Street Chinatown Archaeological Project. (Photo taken 23 January 2003, reprinted courtesy of Market Street

Chinatown Archaeological Project.)

has a significant role to play in investigating the

materiality of Chinese immigration and settlement

throughout the globe. Attention to the stuff

of daily life, whether architecture or ceramics,

grave markers or botanical remains, provides an

opportunity to trace the ways in which Chinese

Main Body-42(3).indd 21

immigrants and their descendants actively negotiated the material realities that conditioned their

lives. The archaeological perspective provides a

necessary partner to the historiography achieved

through analysis of archival records. The studies and resources presented here will serve as

2/7/08 2:35:29 PM

22

HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 42(3)

a springboard for the emergence of new collaborations and perspectives on Overseas Chinese

archaeology and history.

Acknowledgments

Chinese place names in this article follow those

used in The Encyclopedia of the Chinese Overseas (Pan 1999). For conversations and perspectives that greatly contributed to this article, we

thank R. Scott Baxter, Pete Schulz, Bryn Williams, Connie Young Yu, and all the participants

in the Overseas Chinese Archaeology symposium

at the 2006 Annual Meeting of The Society for

Historical Archaeology. We are also grateful to

Stella DOro for sharing her graphic talents in

producing figures 1 and 2.

References

Aarim-Heriot, Najia

2003 Chinese Immigrants, African Americans, and Racial

Anxiety in the United States 18481882. University of

Illinois Press, Urbana.

Allen, Rebecca, R. Scott Baxter, Anmarie Medin,

Julia G. Costello, and Connie Young Yu

2002 Excavation of the Woolen Mills Chinatown (CA-SCL807H), San Jose, 2 vols. Report to California

Department of Transportation, District 4, Oakland,

from Past Forward, Inc., Richmond, CA; Foothill

Resources, Ltd., Mokelumne Hill, CA; and EDAW,

Inc., San Diego, CA.

Allen, Rebecca, and Mark Hylkema

2002 Life along the Guadalupe River: An Archaeological

and Historical Journey. Friends of the Guadalupe River

Park and Gardens, San Jose, CA.

Almaguer, Tomas

1994 Racial Fault Lines: The Historical Origins of White

Supremacy in California. University of California

Press, Berkeley.

American Anthropological Association

1998 Statement on Race. American Anthropological

Association, Arlington, VA <http://www.aaanet.org/

stmts/racepp.htm.>

American Association of Physical Anthropologists

1996 Statement on Biological Aspects of Race. American

Journal of Physical Anthropology 101:569570.

Anderson, Benedict

1993 Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and

Spread of Nationalism. Verson, New York, NY.

Main Body-42(3).indd 22

Asian Women United of California (editor)

1989 Making Waves: An Anthology of Writings by and about

Asian American Women. Beacon Press, Boston, MA.

Ayres, James E.

1984 The Archaeology of Chinese Sites in Arizona. In

Origins and Destinations, Forty-One Essays on Chinese

America. Chinese Historical Society of Southern

California and UCLA Asian American Studies Center,

Los Angeles.

Barnes, Jessica S., and Claudette E. Bennett

2002 The Asian Population: 2000. Census 2000 Briefs and