Professional Documents

Culture Documents

EPI.2006.Unger - Tmih.can Malaria Be Controlled Where Basic Health Services Are Not Used

Uploaded by

derekwwillisOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

EPI.2006.Unger - Tmih.can Malaria Be Controlled Where Basic Health Services Are Not Used

Uploaded by

derekwwillisCopyright:

Available Formats

Tropical Medicine and International Health doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01576.

volume 11 no 3 pp 314–322 march 2006

Can malaria be controlled where basic health services are not

used?

Jean-Pierre Unger1, Umberto d’Alessandro2, Pierre De Paepe1 and Andrew Green3

1 Department of Public Health, Prince Leopold Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium

2 Department of Parasitology, Prince Leopold Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium

1 3 Nuffield Institute for Health, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

Summary objective To assess the potential of integrating malaria control interventions in underused health

services.

methods Using the Piot predictive model, we estimated malaria cure rates by deriving parameters

influencing treatment at home and in health facilities from the best-performing African malaria

programmes and applying them to Yanfolila district, Mali.

results Without any malaria control intervention, the population cure rate is 8.4% with home

treatment, but would be 13% if access to timely treatment were improved (as in Kenya). A further 3.2%

of malaria patients could be cured in institutional settings with more sensitive diagnosis, timely start

of treatment, better compliance (as in Uganda, Tanzania, Ghana) and 80% chloroquine efficacy.

Applied in a setting where 7.6% of malaria patients seek institutional care, these assumptions would

result in a total population cure rate of 14.5%. Increasing the health service user rate from 0.17 in

Yanfolila to 0.95 new cases/inhabitant/year (as in Namibia) would result in half of all malaria patients

attending professional services, raising the cure rate to 26.1%.

conclusion If malaria patients are to be treated and followed-up early and appropriately, basic health

services need to deliver integrated care and be attended by an adequate pool of users. Improved service

user rates and case management can increase malaria cure rates far more than isolated control inter-

ventions can. This has implications for international policies endorsing a narrow disease-based

approach.

keywords health policy, international cooperation, public sector, disease control integration

annual mortality toll of 1.8 million (WHO 1999). In the

Introduction

early 1960s, only 10% of the world’s population was at

Disease control, a focus of international aid in developing risk of contracting malaria. This figure has risen to 40% as

countries, is under severe strain. For example, despite a 10- mosquitoes developed resistance to pesticides and malaria

fold increase in external financing of tuberculosis control in parasites developed resistance to treatment drugs. Malaria

these countries over the last decade, only 27% of the is now spreading to areas previously free of the disease.

pulmonary tuberculosis cases with a positive microscopic This is partly the result of the general conditions in

test result have access to the package devised as part of the developing countries and, in particular, of falling salaries,

2 directly observed treatment short course (DOTS) strategy budget crises, low priority given to social sectors, concen-

(Mahendradhata et al. 2003). Countries such as South tration of government staff in large towns, corruption and

Africa and Zambia suffer from an AIDS prevalence rate patronage. Nevertheless, sector-specific factors cannot be

of >20%. In other countries, such as Botswana and ruled out: the 10-year-old international aid policy (World

Zimbabwe, the rate is approaching 30%. Anti-retroviral Bank 1995) could be a significant one. This policy, which

coverage is very low in regions that need it most: only 2% of admittedly is not always reflected in actual disbursements,

people living with HIV/AIDS in Africa and 7% in south-east recommends a narrow disease-based approach within the

Asia are under anti-retroviral treatment (Buvé et al. 2003). non-for-profit sector, based on disease control prioritiza-

As for malaria, in spite of large-scale control efforts, the tion (World Bank 1994; WHO 2000); the reason for this

World Health Organization (WHO) still talks about an approach is supposedly higher efficiency (Human

314 ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 11 no 3 pp 314–322 march 2006

J.-P. Unger et al. Malaria control

Development Network 1997; Commission of European et al. 2003), both in countries where chloroquine remains

Communities 2002). What the policy amounts to is temporarily the primary drug, such as Mali, and in

allocating the responsibility for disease control to non-for- countries where more complex and expensive protocols

profit facilities: non-integration of health care and disease require the availability of laboratory tests and of skilled

control become practically unavoidable, as health care and professionals.

disease control are allocated to different institutions in Theoretically, case management can be promoted and

practice. Nevertheless, many authors stress the necessity to implemented through both formal public and private

integrate programmes into local health facilities so as to health services and through the informal sector by shop-

achieve a reasonable prospect of successful disease control keepers (Brugha & Zwi 1998). Nevertheless, the latter

(Loretti 1989; Ageel & Amin 1997; Bossyns 1997; Tulloch might prove to be limitedly feasible in developing

1999) although exceptions justifying specific vertical con- countries. The shift to more complex therapeutic protocols

trol programmes are acknowledged. encompassing combined anti-malarial drugs might be more

A recent study by Berkley et al. suggests that bacterial difficult to implement through the informal sector than a

disease may be responsible for more deaths in children than chloroquine monotherapy. Furthermore, drugs of poor

malaria in an area where malaria is endemic (Berkley et al. quality are more likely to be found in the informal sector.

2005). In the same New England Journal of Medicine Within the formal sector, private professional practitioners

3 (NEJM)-issue, an editorial concludes on the necessary could provide another channel for malaria control inter-

provision of comprehensive, integrated and accessible basic ventions, but they are scarce in African rural areas, where

health services (Mulholland & Adegbola 2005). 66% of the population is currently living. In addition, they

Successful implementation of disease control pro- are frequently reluctant to implement national health

grammes may be expected to require health facilities with policy guidelines or to refer their patients to public health

patients. Intuitively, these patients, consulting for various facilities (Lonnroth et al. 1999).

symptoms, represent a pool of users that the programmes The above strongly suggests that the public-interest

need for early case-detection and sufficient follow-up. We sector (NGOs, denominational, city, community, social

assessed the potential of integrating malaria control inter- security and government services) is the appropriate outlet

ventions in basic health services with low curative care to deliver adequate case management (Human Develop-

utilization. To do so, we examined the expected malaria ment Network 1997; WHO 1999). Unfortunately, in

cure rate with a predictive model that includes parameters Africa these services and more particularly government

influencing access to anti-malarial treatment at home and health facilities are underutilized. In Mali, for example,

in health facilities. The parametric values were selected there are 0.15 new cases per inhabitant per year, in Ivory

from published African programmes with the best results. Coast 0.12, in Benin 0.24 and in Guinea 0.34 (Levy-Bruhl

They were applied to a Malian district population (Yan- et al. 1997).

folila), where the health-seeking behaviour of mothers/ The present study aims at verifying whether malaria case

guardians with feverish children had been quantified. management is bound to fail in such settings. If this

One important component of the malaria control strat- hypothesis is verified, it could reasonably apply to any

egy promoted by WHO (2003) is adequate case manage- disease control programme in which case management is

ment (early diagnosis and prompt and efficacious an important component. The recent call of the WHO

treatment). Cost-effectiveness of improvement of case Director General to strengthen health systems (Jong-wook

management has been estimated around US$ 1–8 per 2003) could then be seen as a call to increase access to

4 disease adjusted life years (DALY) averted. It compares general curative health care in the services delivering

favourably with other interventions, such as provision of disease control case management. This requires technical

insecticide-treated bed nets (US$ 19–85, US$ 4–10 for the and financial support to such basic health services.

re-impregnation of nets), residual spraying (US$ 32–58),

chemoprophylaxis for children (US$ 3–12) and intermit-

Methods

tent preventive treatment during pregnancy (US$ 4–29)

(Goodman et al. 1999). Controversy has been stirred by an We reviewed the literature on malaria case management in

increasing resistance to chloroquine and sulfadoxine/pyri- Africa with the Piot operational model which proved useful

methamine (Attaran et al. 2004), but while the introduc- in the assessment of disease control programmes for

tion of Artemesinine Combination Therapy (ACT) might tuberculosis (Piot 1967), malaria (Mumba et al. 2003),

change these cost-effectiveness ratios (Belsky et al. 2004; sleeping sickness (Robays et al. 2004) and sexually trans-

Coleman et al. 2004; Webb et al. 2004), it would not alter 5 mitted diseases (Buvé et al. 2001). This ‘operational

the importance of relying on case management (Moerman analysis’ model aims at estimating (1) treatment rates: the

ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 315

Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 11 no 3 pp 314–322 march 2006

J.-P. Unger et al. Malaria control

number of cases correctly treated over the number of Data were collected in a study conducted in November

symptomatic cases in the population; and (2) cure rates: the 1998, when no specific malaria control programme was

number of cases clinically cured over the number of being implemented. The method employed and the results

symptomatic cases in the population. have been reported elsewhere (Thera et al. 2000). First, a

It encompasses different steps between illness onset and structured questionnaire about health-seeking behaviour

completion of treatment, such as patients’ awareness and was administered to randomly selected mothers/guardians.

motivation, treatment in the home setting or in public Parasitaemia and body temperature were determined in

health facilities, correctness of diagnosis and treatment, every child whose mother thought that he/she was sick at

compliance with (Mumba et al. 2003) and sensitivity to the time of interview and the sensitivity and specificity of

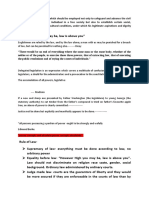

drugs. Figure 1 outlines the application of the Piot model the mothers’ diagnoses of uncomplicated malaria were

to malaria. assessed. For children who according to their mothers’

As the quality of professional decision making was not definition and perception had had malaria in the previous

known, we first re-analyzed cure rate data from Yanfolila rainy season, the optimal dose of chloroquine was calcu-

health district in Mali to determine the effectiveness of lated on the basis of age and then compared with the dose

detection and treatment in home settings, together with a given by the mother.

fictitious 100% cure rate in patients attending professional Second, we used the results derived from studies in other

health services. African countries, where malaria control programmes were

more effective and/or new interventions were tested, to

Patients with assess their potential impact on malaria cure rates where

uncomplicated clinical health service use is low. To do so, we entered data into the

malaria

model from settings where the ‘best’ results had been

published. These settings were:

• the Tanzanian first-line services (Font et al. 2001),

G: Public health A: Home

facility management where the programme aimed at increasing the pro-

portion of appropriate treatment in patients with

malaria symptoms;

• Ghana, where a (quasi-experimental design) study

H: Sensitivity of B: Sensitivity of tested the impact of a combination of improved

professional diagnosis mother’s diagnosis

information provision to patients and drug labelling

on compliance to recommended oral chloroquine

regimens, for the outpatient management of acute

C: Choose modern uncomplicated malaria (Agyepong et al. 2002);

treatment

• Uganda, where professional sensitivity was relatively

high because professionals tend to treat most feverish

D: Access modern patients with chloroquine (plus other treatment if

treatment necessary) (Lubanga et al. 1997); and

• Kenya, where shopkeepers were trained in malaria

case management (Marsh et al. 1999).

I: Start appropriate E: Start appropriate

treatment (drug and treatment (drug and Third, we looked at the impact of achieving a service use

dosage) dosage) rate of 0.95 new cases/inhabitant/year, as in Namibia in

1996 (Stryckman 1996; el Obeid et al. 2001), compared

with only 0.17 new cases per inhabitant per year in

J: Compliance

Yanfolila. In 2003, 50% of malaria patients in Namibia

were treated in health services (Oxfam 2003). We exam-

F: Sensitivity to

chloroquine ined the potential impact of higher service use rates in

Yanfolila, together with the results for the best interven-

tions targeting health professionals.

Cure rate t-Tests for proportion were calculated for each para-

metric value to determine its confidence interval, if not

Figure 1 Operational model of malaria case management to provided by the original article referred to. Maximum

determine the clinical cure rate.

316 ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 11 no 3 pp 314–322 march 2006

J.-P. Unger et al. Malaria control

J: Compliance

error rates of the model were then computed while using a

two-step procedure. First, they were computed for the

83.5 ± 6.6

home treatment and professional treatment groups using

the formula

qffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

SDðABÞ ¼ A2 SD2 ðBÞ þ B2 SD2 ðAÞ

public facility

treatment in

appropriate

Second, their sum’s standard deviation was established

65 ± 2.3

I: Start

using the formula

qffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

SDðA þ BÞ ¼ A2 SD2 ðAÞ þ B2 SD2 ðBÞ

H: Sensitivity

professional

where co-variance is equal to zero, assuming that the terms

97.8 ± 1.8

diagnosis

are independent.

of

Results

G: Attend

7.6 ± 2

Table 1 provides data derived from Yanfolila and other

facility

public

health

African settings. Table 2 provides cure rates under differ-

50

ent parametric assumptions. Both tables present results

using different parameters from A to J, as explained in

K: Sensitivity

chloroquine

Figure 1. In Yanfolila, without any specific malaria control

interventions, the cure rate in home settings was

80.00

8.4 ± 2.3% (a), corresponding with a 9.56% population

to

cure rate at 88 ± 3.2% of treatment at home (Table 2). A

64.6 ± 11.6

appropriate

further 6.1% of malaria patients could be cured through E: Start an

72.9 ± 5.1

treatment

professional settings (b) assuming a treatment rate of

at home

100% in professional settings; 7.6% of Yanfolila malaria

patients seeking care in professional services; and 80%

chloroquine efficacy (as in Mali). Adding (a) to (b), the

82.2 ± 3.6

D: Access

treatment

56.5 ± 9

total population cure rate in Yanfolila would be an

modern

unsatisfactory 14.5% under these assumptions.

As a 100% treatment rate is impossible to achieve, we

applied the following estimates to assess the likely impact

C: Choose

82.1 ± 6.4

*See Figure 1: operational model of malaria case management.

treatment

of malaria control interventions designed to improve

modern

malaria case management in a professional environment:

using Tanzanian data, 65 ± 2.3% of patients with malaria

Table 1 Parameters derived from African countries

symptoms were assumed to receive appropriate treatment.

B: Sensitivity

39.9 ± 0.49

of mother’s

As in a Ghanaian study, the maximum post-intervention

37.4 ± 5.7

diagnosis

proportion of minimum daily adherence to chloroquine

tablets (preferred to syrup) was put at 83.5 ± 6.6%

(Agyepong et al. 2002). Based on the Ugandan study,

sensitivity of professional diagnosis was put at

management

A*: Home

97.8 ± 1.8%. A combination of these best practice inter-

88 ± 3.2

ventions suggests a cure rate of 3.2 ± 0.9% in professional

services.

33

In the home treatment group, training shopkeepers in

Data

Kenya resulted in an increase in appropriate use of over-

set

the-counter chloroquine by at least 61.5%. The Kenya

1

2

3

4

5

6

experiment also resulted in a sales increase of 45% in

Parameters

Yanfolila

Tanzania

purchased anti-malarial drugs. Applying these figures to

Namibia

(% ±CI)

Uganda

Ghana

(Mali)

Kenya

the Yanfolila home case management data would increase

the access to modern treatment from 56.9% to

ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 317

Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 11 no 3 pp 314–322 march 2006

J.-P. Unger et al. Malaria control

26.1 (21.2 + 4.9)

82.2 ± 3.6%, and to 72.9 ± 5.1% of people receiving

14.5 (8.4 + 6.1)

11.6 (8.4 + 3.2)

15.2 (13 + 3.2)

appropriate drug and dosage, instead of 64.6 ± 11.6%.

Total cure

rates (%)

This approach would increase the cure rate by 18% in the

self-treatment group – from 11.7% to 13% of total

patients. Combining the Uganda/Tanzania/Ghana results

in a professional setting, patients with an intervention

similar to that in Kenya might result in a total cure rate in

cure rates (%)

the general population of 16.2%.

Professional

A hypothetical increase in the health service user rate

from to 0.95 new cases/inhabitant/year applied to the

6.1

3.2

26 Yanfolila setting could, as in Namibia in 2003, result in

50% of patients with malaria attending professional health

services, a more than sixfold increase from current values.

This service use rate, together with the interventions in the

Home cure

rates (%)

professional setting set out above, could result in a cure

9.56

rate in the total population of 26.1%, 4.9 ± 0.9% for

4.9

8.4

13

home treatment and of 21.2 ± 1.8% for professional

treatment.

(A1*B1*C1*D1*E1*F1)

(A1*B1*C1*D1*E1*F1)

(A1*B1*C1*D7*E5*F1)

(A6*B1*C1*D1*E1*F1)

Discussion

A1*B1*C1*D1*E1*F1

A1*B1*C1*D7*E5*F1

+ (G1*H4*I2*J3*F1)

+ (G1*H4*I2*J3*F1)

+ (G6*H4*I2*J3*F1)

+ (G1*100%* F1)

B1*C1*D1*E1*F1

Yanfolila is representative of other west-African countries

G1*H4*I2*J3*F1

G6*H4*I2*J3*F1

G1*100%* F1

in terms of population structure (median age is 16.3 years

in Mali, 16.4 in Benin and 17.7 in Guinea), density (15.5

Formula

inhabitants/km2 in Sikasso district, 57 in Benin and 30 in

Guinea), epidemiology (low HIV prevalence, tuberculosis

prevalence rate around 200 per 100 000 inhabitant),

health system inputs (a small part of government budget

for health and high dependency on external resources for

Total cure rate in Yanfolila, assuming 100% treatment rate through professional

Total cure rate in Yanfolila assuming that Uganda/Tanzania/Ghana interventions

Total cure rate applying Namibia services utilization rates and Tanzania/Ghana/

Cure rate in Yanfolila population through professional treatment assuming that

Cure rate in professional setting applying Namibia services utilization rates and

health), and limited access to health care, resulting in a low

Cure rate through professional management applying Uganda/Tanzania/Ghana

Total cure rate applying Kenya shopkeepers intervention in home setting and

use rate of public services.

In Yanfolila, where use of public health services was low

(0.17 new cases/inhabitant/year), the proportion of malaria

patients seeking professional treatment was only 7.6%.

Table 2 Cure rates under different parametric assumptions

Cure rate in home-setting with Kenya shopkeepers intervention

Uganda/Tanzania/Ghana interventions in professional settings

Even a hypothetical professional treatment rate of 100%

would not raise the total cure rate beyond 11.2%. In this

context, the combination of best-published programmes in

home and professional settings (including shopkeepers’

training) could only increase the total population cure rate

Population cure rate in Yanfolila home setting

to 16.2%. Instead, an adequate use rate as in Namibia,

are applied in Yanfolila professional setting

together with the interventions in the professional setting,

Tanzania/Ghana/Uganda interventions

permits a 2.2-fold increase with a 26.1 ± 2.1% cure rate in

Cure rate in Yanfolila home setting

the total population.

treatment rate is 100% treatment

For parameters A–J, see Figure 1.

Cure rates in different settings

This assumption is conservative, as health service

attendance may motivate some users of traditional medi-

cine to take professional treatment. We also assumed that,

Uganda interventions

applying Namibia’s utilization rate, 50% of malarial

patients would be treated in the health services in Yanfolila

interventions

and that an increase in symptomatic malaria patients

management

attending health services (+42.4%, concretely from 7.6%

to 50%) would result in a similar reduction in home care

frequency ()42.4%, namely from 75.8% to 33.4%).

318 ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 11 no 3 pp 314–322 march 2006

J.-P. Unger et al. Malaria control

The Ugandan approach is part of the Integrated Man- pharmaceutical companies. A fourth factor is described by

agement of Childhood Illnesses programme. It minimizes numerous studies that highlight the inadequacy of inter-

false negative cases, particularly among patients associ- ventions directed solely at enhancing provider knowledge,

ating malaria with other aetiology of fever, particularly even to professional providers (Paredes et al. 1996) who

acute lower respiratory infection among children, but leads are theoretically at least motivated by a strong ethical

to a high false positive rate. Access to laboratory equip- identity. Lastly, in other contexts such as Uganda, the

ment is poor in most developing countries and, conse- sensitivity of the mothers’ diagnosis of malaria was found

quently, high sensitivity and specificity is difficult to to be only 37% (Lubanga et al. 1997). In that setting,

achieve. Our sensitivity of diagnosis rate of 98%, with low training of shopkeepers will even have a smaller impact

specificity, achieved by malaria treatment given to all than in Yanfolila.

febrile patients, is undesirable in view of its poor efficiency Finally, the parameters used may not be independent

and contribution to drug resistance. This strategy may be from one another, although this is an assumption of the

acceptable with cheap treatment as in Mali, but not in Piot model. For instance, sensitivity of the mother’s

chloroquine-resistant countries where new high-cost treat- diagnosis, access to modern treatment or choice of modern

ment combinations are introduced. Improvement in the treatment and then the start of treatment in a public

diagnosis process is needed (through staff training and health facility may be correlated. This simplification, if

better criteria), but financial considerations will inevitably confirmed, would lead to overestimating the impact of

reduce professional sensitivity. the best African programmes in Yanfolila and strengthen

Training informal providers (shopkeepers) permits a further our hypothesis.

54.7% gain in cure rate in the self-treatment group, but Standardized malaria case management is usually integ-

would lift the total cure rate to only 16.2%. Moreover, this rated in non-for-profit, publicly oriented services. Until

hypothesis overestimates the impact of activities directed to convincing evidence shows that the private-for-profit sector

the self-treatment group because: (1) drug intake consid- can efficiently undertake disease control activities, these

erations have not been included in the model. In the publicly oriented services will need to increase their

Ghanaian study, compliance data (83%) can be considered generally low use rates to obtain more satisfactory malaria

as drug intake data. Where shopkeepers are trained, an cure rates. Complementary strategies are required and

increase in purchased drugs does not guarantee correct include the following elements:

drug intake; when symptoms disappear, people often stop

• access to essential drugs in health services;

their medication and drugs are saved for future episodes or

• in-service training and service reorganization, which

are given to family members. This intake is probably better

are needed to increase service accessibility, accepta-

in professional than in home treatment groups, as malaria

bility, and introduce patient-centred, bio-psychosocial

control programmes begin to rely on direct observation of

care (Unger et al. 2002);

treatment for single dose regimens and health education

• support of human resource policy. No health policy

advice may be more adequately given by health profes-

can succeed without skilled staff. Health professionals

sionals. (2) Treatment delay is an important factor of

need decent salaries, a merit-based selection process,

prognosis deterioration. Experience suggests that patient

an appropriate training programme and job security.

delay tends to be high when use rates are low. In Burkina

Consideration should be given to recruiting experi-

Faso, low overall effectiveness of malaria management was

enced staff and offering them posts in district health

largely because of low use of health services (Krause &

management teams, with a joint responsibility to

Sauerborn 2000). Early detection of severe cases and timely

improve health-care services, whilst implementing

hospital referral is more frequent in the professional group,

disease control programmes.

but this factor was not taken into account.

• support to district and regional hospitals. These are

Furthermore, several factors impair the scaling-up of

indispensable. They are complementary components

pilot projects focusing on shopkeepers: one factor is that

of first-line health care. Public hospitals need to be

training shopkeepers to prescribe rationally for multiple

bolstered by greater investments, a reliable operating

diseases is not realistic, although it led to positive results

budget and a management that aims to integrate

for sexually transmitted infections (Jacobs et al. 1999),

resources and structures into a system. Such a process

family planning (Agha et al. 1997) and malaria in Kenya.

can be led both by health district teams and/or

Another factor is that professional organizations may resist

networks of committed professionals.

approval of less-qualified providers, which reduces the

feasibility of this approach. Also, the practice of many Together with other components of malaria control,

private providers is determined by biased information from such as impregnated bed nets, interventions aiming at

ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 319

Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 11 no 3 pp 314–322 march 2006

J.-P. Unger et al. Malaria control

improving use rates of general health services, combined

Acknowledgements

with improvement in professional malaria case manage-

ment will have a much deeper impact on malaria cure rates We would like to thank Drs Veerle Vanlerberghe, Marleen

than malaria control interventions on their own. The Boelaert, Joris Menten and two anonymous reviewers for

number of existing vertical disease control programmes their comments. This research has been made possible

and candidate diseases for new programmes jeopardizes thanks to the support of the Belgian Cooperation.

the feasibility of their joint implementation.* These two

factors bear several consequences for international health

References

policies, which, so far, have promoted a narrow disease-

based approach – minimizing the chance of genuine Ageel AR & Amin MA (1997) Integration of schistosomiasis-

integration. control activities into the primary-health-care system in the

First, the requirement of more patients attending public- Gizan region, Saudi Arabia. Annals of Tropical Medicine and

oriented services amounts to a plea for competition for Parasitology 91, 907–915.

general health-care delivery between subsidized services Agha S, Squire C & Ahmed R (1997) Evaluation of the Green Star

Pilot Project. Population Services International, Washington

delivering disease control programmes and the others.

DC.

Second, disease control initiatives need to be embedded

Agyepong IA, Ansah E, Gyapong M, Adjei S, Barnish G & Evans

into general strategies to revitalize those services in which D (2002) Strategies to improve adherence to recommended

disease control programmes are implemented. Aid funds chloroquine treatment regimens: a quasi-experiment in the

should be directed to public-oriented services, character- context of integrated primary health care delivery in Ghana.

ized by specific management and care delivery (Unger et al. Social Science & Medicine 55, 2215–2226.

2003). Subsidized disease control programmes should not Attaran A, Barnes KI, Curtis C et al. (2004) WHO, the Global

be entitled to interfere with the standard health-care Fund, and medical malpractice in malaria treatment. Lancet

delivery in services where they are implemented. The 363, 237–240.

Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, for Belsky L, Lie R, Mattoo A, Emanuel EJ & Sreenivasan G (2004)

The general agreement on trade in services: implications for

instance, should use its resources not only to control these

health policymakers. Health Affairs (Millwood) 23, 137–145.

diseases, but also to strengthen national health services,

Berkley JA, Lowe BS, Mwangi I et al. (2005) Bacteremia among

and this should be reflected in actual disbursements to children admitted to a rural hospital in Kenya. New England

applying countries. Journal of Medicine 352, 39–47.

Which research priorities could be designed to maximize Bossyns P (1997) Big programmes, big errors? Lancet 350, 1783–

Piot model terms? Because of its resistance status, Mali is 1784.

one of the last places in the world where chloroquine can Brugha R & Zwi A (1998) Improving the quality of private sector

be used. New drugs, such as artemisinine combinations, delivery of public health services: challenges and strategies.

will be more effective than the values used in our model. Health Policy and Planning 13, 107–120.

Their cost will probably make a diagnostic test mandatory, Buvé A, Changalucha J, Mayaud P et al. (2001) How many pa-

resulting in an undetermined amount of false negatives and tients with a sexually transmitted infection are cured by health

services? A study from Mwanza region, Tanzania. Tropical

positives. Operational research will thus be needed to

Medicine and International Health 6, 971–979.

develop clinical decision trees according to local values of

Buvé A, Kalibala S & McIntyre J (2003) Stronger health systems

malaria incidence, finances and availability of diagnostic for more effective HIV/AIDS prevention and care. International

tests and treatments; evaluate home-based treatment of Journal of Health Planning and Management 18, S41–S51.

malaria with new drugs; and implement in practice Coleman PG, Morel C, Shillcutt S, Goodman C & Mills AJ (2004)

molecular markers of resistance to these new drugs. A threshold analysis of the cost-effectiveness of artemisinin-

Meanwhile, we must monitor resistance to chloroquine at based combination therapies in sub-saharan Africa. American

regional level in west African countries where chloroquine Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 71, 196–204.

is still in use. Commission of European Communities (2002) Communication

from the Commission to the Council and the European Parlia-

ment: health and poverty reduction in developing countries.

Report 129, European Commission, Brussels, Belgium.

*For instance, the so-called neglected diseases (soil transmitted Font F, Alonso GM, Nathan R et al. (2001) Diagnostic accuracy

helminths and schistosomiasis, lymphatic filariasis, leprosy, vis- and case management of clinical malaria in the primary health

ceral leishmaniasis, Guinea worm, trypanosomiasis, trachoma, services of a rural area in south-eastern Tanzania. Tropical

cholera and rabies); in other communicable pathologies as Medicine and International Health 6, 423–428.

shigellosis and salmonellosis; and in non-communicable diseases Goodman CA, Coleman PG & Mills AJ (1999) Cost-effectiveness

which increase with the demographic transition. of malaria control in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 354, 378–385.

320 ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 11 no 3 pp 314–322 march 2006

J.-P. Unger et al. Malaria control

Human Development Network (1997) Health, Nutrition and el Obeid S, Mendelsohn J, Lejars M, Forster N & Brulé G (2001)

Population. Sector Strategy Paper. World Bank, Washington, Health in Namibia: Progress and Challenges, Chapter 3: Access

USA. and Utilization. Research and information services of Namibia,

Jacobs B, Witworth J, Lwanga A & Pool R (1999) Feasibility and 9 Windhoek, Namibia. ISBN: 99916-780-0-X.

Acceptability of Marketing Pre-Packaged Treatment for Men Paredes P, de la Pena M, Flores-Guerra E, Diaz J & Trostle J

with Urethral Discharge (Clear 7): Results from a Controlled (1996) Factors influencing physicians’ prescribing behaviour in

Trial in Uganda. MRC Research programme on AIDS/Uganda the treatment of childhood diarrhoea: knowledge may not be the

Virus Research Institute, Entebbe. clue. Social Science & Medicine 42, 1141–1153.

Jong-wook L (2003) Global health improvement and WHO: Piot MA (1967) A Simulation Model of Case Finding and Treat-

shaping the future. Lancet 362, 2083–2088. ment in Tuberculosis Control Programmes. WHO, Geneva.

Krause G & Sauerborn R (2000) Comprehensive community Robays J, Bilengue C, Van Der Stuyft P et al. (2004) The effect-

effectiveness of health care. A study of malaria treatment in iveness of active population screening and treatment for sleeping

children and adults in rural Burkina Faso. Annals of Tropical sickness control in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Tropical

Paediatrics 20, 273–282. Medicine and International Health 5, 542–550.

Levy-Bruhl D, Soucat A, Osseni R et al. (1997) The Bamako Ini- Stryckman B (1996) Comparative Analysis of Cost, Resource Use,

tiative in Benin and Guinea: improving the effectiveness of pri- and Financing of District Health Services in Sub-Saharan Africa

mary health care. International Journal of Health Planning and and Asia. UNICEF, New York, pp. 37.

Management 12 (Suppl. 1), S49–S79. The Global Fund (2003) Scaling up the Fight Against HIV/AIDS,

Lonnroth K, Thuong LM, Linh PD & Diwan VK (1999) Delay and TB and Malaria in Namibia. Section IV: Detailed Information

discontinuity – a survey of TB patients’ search of a diagnosis in a on Malaria (Goal 3) Component of the Proposal. The Global

diversified health care system. International Journal of Tuber- Fund.

culosis and Lung Disease 3, 992–1000. Thera MA, D’Alessandro U, Thiero M et al. (2000) Child malaria

Loretti A (1989) Leprosy control: the rationale of integration. treatment practices among mothers in the district of Yanfolila,

Leprosy Review 60, 306–316. Sikasso region, Mali. Tropical Medicine and International

Lubanga RG, Norman S, Ewbank D & Karamagi C (1997) Ma- Health 5, 876–881.

ternal diagnosis and treatment of children’s fever in an endemic Tulloch J (1999) Integrated approach to child health in developing

malaria zone of Uganda: implications for the malaria control countries. Lancet 354 (Suppl. 2), SII16–SII20.

programme. Acta Tropica 68, 53–64. Unger JP, Van Dormael M, Criel B, Van der Vennet J & De

Mahendradhata Y, Lambert ML, Van Deun A, Matthys F, Bo- Munck P (2002) A plea for an initiative to strengthen family

elaert M & Van der Stuyft P (2003) Strong general health care medicine in public health care services of developing countries.

systems: a prerequisite to reach global tuberculosis control tar- International Journal of Health Services 32, 799–815.

gets. International Journal of Health Planning and Management Unger JP, Marchal B & Green A (2003) Quality standards for

18, S53–S65. health care delivery and management in public-oriented health

Marsh VM, Mutemi WM, Muturi J et al. (1999) Changing home services. International Journal of Health Planning and Man-

treatment of childhood fevers by training shop keepers in rural agement 18, S79–S88.

Kenya. Tropical Medicine and International Health 4, 383–389. Webb D, D’Alessandro C, Bull N & Sainz T (2004) Meeting the

Moerman F, Lengeler C, Chimumbwa J et al. (2003) The con- Challenge? A Comprehensive Review of the First Three Funding

tribution of health-care services to a sound and sustainable Rounds of the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and

malaria-control policy. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 3, Malaria. Save the Children, London.

99–102. WHO (1999) The World Health Report 1999: Making a Differ-

Mulholland EK & Adegbola RA (2005) Bacterial infections. A ence. WHO, Geneva.

major cause of death among children in Africa. New England WHO (2000) The World Health Report 2000 – Health Systems:

Journal of Medicine 352, 75–77. Improving Performance. WHO, Geneva.

Mumba M, Visschedijk J, van Cleeff M & Hausman B (2003) A WHO (2003) Roll Back Malaria Technical Strategies. http://

Piot model to analyse case management in malaria control www.rbm.who.int.

programmes. Tropical Medicine and International Health 8, World Bank (1994) Better Health in Africa. Experience and

544–551. lessons learned. A World Bank Publication, Washington, DC.

Oxfam (2003) False hope or new start? The Global Fund to fight World Bank (1995) Better Health in Africa: Experience and

6,7

6 HIV/AIDS, TB and Malaria. Oxfam briefing paper, 24. Lessons Learned. The World Bank, Washington, DC.

Corresponding Author Pierre De Paepe Department of Public Health, Prince Leopold Institute of Tropical Medicine, Nationalestraat

10 155, 2000 Antwerp, Belgium. Tel.: +32 3 247 6541; Fax: +32 3 247 6258; E-mail: pdpaepe@itg.be

ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 321

Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 11 no 3 pp 314–322 march 2006

J.-P. Unger et al. Malaria control

Peut on contrôler la malaria dans les endroits où les de services de santé de base sont sous-utilisés?

objectif Evaluer la possibilité d’intégrer les interventions pour le contrôle de la malaria dans les services de santé sous-utilisés.

méthodes Sur base du modèle prédictif de Piot, nous avons estimé les taux de guérison de la malaria à partir de paramètres influençant le traitement à

domicile et dans les services de santé, dans les meilleurs programmes africains contre la malaria, et les avons appliqué dans le district de Yanfolila

au Mali.

résultats Sans traitement de la malaria, le taux de guérison de la population est de 8,4%. Ce taux atteindrait 13% si le délais d’accès au traitement

était amélioré comme dans le cas du Kenya. Un taux supplémentaire de 3,2% de patients malariques pourraient être guéris dans les institutions

utilisant un diagnostic plus sensible, un traitement administrée à temps, une meilleure compliance (cas de l’Ouganda, de la Tanzanie et du Ghana)

et avec 80% d’efficacité de la chloroquine.

Lorsqu’elles sont appliquées dans un endroit où 7,6% des patients malariques ont recours à des service institutionnels, ces assomptions résulteraient en

un taux total de guérison de la population de 14,5%. L’augmentation de l’usage des services de santé de 0,17 (à Yanfolila) à 0,95 nouveaux cas/habitant/

année (comme en Namibie) résulterait à 50% de tous les patients malariques recourant à des services professionnels. Cela élèverait le taux de

guérison à 26,1%.

conclusion Si les patients malariques doivent être traitées et suivis tôt et de façon appropriée, les services de santé de base devraient offrir des soins

intégrés et être fréquentés par un nombre adéquat d’utilisateurs. Des taux améliorés des utilisateurs des services et de la prise en charge des cas,

peuvent augmenter les taux de guérison de la malaria beaucoup plus que ne peuvent les cas isolés d’intervention.

mots clés services de santé, coopération internationale, secteur publique, soins integreés

¿Puede controlarse la malaria en donde no se utilizan los servicios de salud básicos?

objetivo Evaluar el potencial de integrar las intervenciones para el control de la malaria en servicios de salud sub-utilizados

métodos Utilizamos el modelo predictivo de Piot para estimar las tasas de curación de la malaria. Los parámetros que influencian el tratamiento en

casa y en centros sanitarios se derivaron de los mejores programas Africanos de malaria y fueron aplicados al distrito de Yanfolila, en Mali.

resultados En ausencia de cualquier intervención de control de malaria, la tasa de curación de la población es del 8.4% con tratamiento domiciliario.

Esta tasa de curación es del 13% si el acceso a un tratamiento a tiempo es mejorado (como en Kenia). Un 3.2% adicional de pacientes con malaria,

podrı́a curarse en centros institucionales con una mayor sensibilidad en el diagnóstico, con un tratamiento adecuado desde el comienzo y con una mejora

en el cumplimiento (como en estudios realizados en Uganda, Tanzania y Ghana) y una eficacia de la cloroquina del 80%. Estas asunciones, aplicadas a

lugares en las que el 7.6% de los pacientes con malaria buscan cuidados en centros asistenciales, resulta en una tasa de curación poblacional del 14.5%.

Aumentar la tasa de uso del 0.17 (en Yanfolila) a 0.95 nuevos casos/habitante/año (como en Namibia) resultarı́a en la mitad de todos los pacientes con

malaria acudiendo a servicios profesionales, doblando ası́ la tasa de cura y aumentándola al 26.1%.

conclusión Nuestro estudio demuestra la necesidad de servicios básicos en salud, prestando una atención integrada y utilizados por un número

adecuado de usuarios, que facilite la detección temprana de casos y un seguimiento suficiente. Una mejora en las tasas de respuesta de servicios y manejo

de casos puede aumentar las tasas de cura para malaria mucho más que intervenciones de control aisladas. Esto tiene implicaciones en las polı́ticas

internacionales que apoyan una aproximación limitada al control de enfermedades.

palabras clave malaria, polı́tica en salud, cooperación internacional, sector público, control integrado de la enfermedad

322 ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

You might also like

- 2019 Article 7986Document10 pages2019 Article 7986Siti AisyahNo ratings yet

- 82681-Article Text-199018-1-10-20121029Document8 pages82681-Article Text-199018-1-10-20121029sudirman efendiNo ratings yet

- Improved Malaria Case Management in Formal Private Sector Through Public Private Partnership in Ethiopia: Retrospective Descriptive StudyDocument11 pagesImproved Malaria Case Management in Formal Private Sector Through Public Private Partnership in Ethiopia: Retrospective Descriptive StudyTesfayeNo ratings yet

- Treatment OutcomesDocument7 pagesTreatment OutcomestarisafidiaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Challenges Faced by Health Workers Managing Patients With Severe Malaria in Kanyabwanga Health Centre III Mitooma District UgandaDocument16 pagesEvaluation of The Challenges Faced by Health Workers Managing Patients With Severe Malaria in Kanyabwanga Health Centre III Mitooma District UgandaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Directly Observed TreatmentDocument9 pagesDirectly Observed TreatmentNovelia CarolinNo ratings yet

- Inhibitors To Control of Malaria Among Resident of Eleme Local Government Area of Rivers StateDocument9 pagesInhibitors To Control of Malaria Among Resident of Eleme Local Government Area of Rivers Stateemmanuelnwa943No ratings yet

- Jurnal Internasional Mikrobiologi Dan Parasitologi-Malaria Di NigeriaDocument15 pagesJurnal Internasional Mikrobiologi Dan Parasitologi-Malaria Di NigeriaVicka Fitri EnjelinaNo ratings yet

- Assessment To Compliance of Tuberculosis Treatment Among Tuberculosis PatientsDocument21 pagesAssessment To Compliance of Tuberculosis Treatment Among Tuberculosis PatientsabdulNo ratings yet

- Malaria and Health Promotion ApproachDocument20 pagesMalaria and Health Promotion ApproachSantepromoNo ratings yet

- Tuberculosis Infection Control Practices and AssocDocument12 pagesTuberculosis Infection Control Practices and AssocchalachewNo ratings yet

- Who/Unicef Joint StatementDocument8 pagesWho/Unicef Joint Statementyuni020670No ratings yet

- Global Health Paper Final DraftDocument22 pagesGlobal Health Paper Final Draftapi-285132682No ratings yet

- International Standards For Tuberculosis Care (2) 2006Document16 pagesInternational Standards For Tuberculosis Care (2) 2006Udsanee SukpimonphanNo ratings yet

- Mjhid 6 1 E2014070Document8 pagesMjhid 6 1 E2014070Khoiril AnwarNo ratings yet

- 2016 Article 1588Document12 pages2016 Article 1588ArcciPradessatamaNo ratings yet

- Zambia Study Dec 2019Document9 pagesZambia Study Dec 2019AbiodunOlaiyaPaulNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Health Information Management Professionals Towards Integrated Disease Surveillance & Response (IDSR) in Abuja, Nigeria.Document48 pagesAssessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Health Information Management Professionals Towards Integrated Disease Surveillance & Response (IDSR) in Abuja, Nigeria.Victor Chibueze IjeomaNo ratings yet

- Malaria JournalDocument11 pagesMalaria JournalEstiPramestiningtyasNo ratings yet

- Discussion:: PreventionDocument9 pagesDiscussion:: PreventionAhmed MustafaNo ratings yet

- Health System in NigeriaDocument8 pagesHealth System in NigeriaTushar BaidNo ratings yet

- Long Walk TBDocument3 pagesLong Walk TBdellanurainiNo ratings yet

- 388-Article Text-1059-1-10-20200112Document3 pages388-Article Text-1059-1-10-20200112Nurhaliza AnjliNo ratings yet

- Executive SummaryDocument1 pageExecutive SummaryFadini Rizki InawatiNo ratings yet

- Vector Borne Disease Control Programme: Department of Public Health, Ministry of HealthDocument10 pagesVector Borne Disease Control Programme: Department of Public Health, Ministry of HealthSathish KumarNo ratings yet

- 2011 - Frank Baiden - TMIH - Would Rational Use of Antibiotics Be Compromised in Era of TestingDocument3 pages2011 - Frank Baiden - TMIH - Would Rational Use of Antibiotics Be Compromised in Era of TestinggrowlfunNo ratings yet

- 2018 Article 314Document11 pages2018 Article 314marisaNo ratings yet

- Vol. 1 Issue 4 April 2008 - 1Document6 pagesVol. 1 Issue 4 April 2008 - 1Maricris RicanaNo ratings yet

- Cost Effectiveness of A Care Program For HIV AIDS Patients - 2016 - Value in HeDocument8 pagesCost Effectiveness of A Care Program For HIV AIDS Patients - 2016 - Value in HeSansa LauraNo ratings yet

- Edited-AN EVALUATION OF HEALTH PROMOTION AND INTERVENTION ON MALARIA PREVENTION THROUGH DISTRIBUTION OF INSECTICIDE-TREATED NETs (ITNs) IN OBUBRA, IKOM AND OGOJA LGAs OF CROSS-RIVER STATE NIGERIADocument22 pagesEdited-AN EVALUATION OF HEALTH PROMOTION AND INTERVENTION ON MALARIA PREVENTION THROUGH DISTRIBUTION OF INSECTICIDE-TREATED NETs (ITNs) IN OBUBRA, IKOM AND OGOJA LGAs OF CROSS-RIVER STATE NIGERIAAbiola AbrahamNo ratings yet

- The Role of a Pharmacist in the Analysis of Adherence Rates and Associated Factors in HIV-Patients Registered on Centralized Chronic Medicines Dispensing and Distribution (CCMDD) Programme in the Public Sector in South AfricaDocument11 pagesThe Role of a Pharmacist in the Analysis of Adherence Rates and Associated Factors in HIV-Patients Registered on Centralized Chronic Medicines Dispensing and Distribution (CCMDD) Programme in the Public Sector in South AfricaSabrina JonesNo ratings yet

- Reported Incidence of Fever For Under-5 Children in Zambia: A Longitudinal StudyDocument7 pagesReported Incidence of Fever For Under-5 Children in Zambia: A Longitudinal StudyBassim BirklandNo ratings yet

- Background/Situational AnalysisDocument7 pagesBackground/Situational AnalysisSimon DzokotoNo ratings yet

- Recent Developments in The Diagnosis and Management of TuberculosisDocument8 pagesRecent Developments in The Diagnosis and Management of TuberculosisRhahahaNo ratings yet

- Rural-Urban Comparison On Mothers' Media Access and Information Needs On Dengue Prevention and ControlDocument83 pagesRural-Urban Comparison On Mothers' Media Access and Information Needs On Dengue Prevention and ControlBuen Josef Cainila AndradeNo ratings yet

- Malaria Treatment-Seeking Behaviour and Its Associated FactorsDocument34 pagesMalaria Treatment-Seeking Behaviour and Its Associated FactorsDaniel BoibanNo ratings yet

- Malaria ControlDocument16 pagesMalaria ControlSutirtho Mukherji100% (1)

- NIH Public Access: Treatment As Prevention-Where Next?Document15 pagesNIH Public Access: Treatment As Prevention-Where Next?Leon L GayaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge of Malaria Prevention Among Pregnant Women and Female Caregivers of Under Five Children in Rural Southwest NigeriaDocument14 pagesKnowledge of Malaria Prevention Among Pregnant Women and Female Caregivers of Under Five Children in Rural Southwest NigeriaAngel Ellene Marcial100% (1)

- Journal of Clinical Tuberculosis and Other Mycobacterial DiseasesDocument16 pagesJournal of Clinical Tuberculosis and Other Mycobacterial DiseasesIlna RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Project WorkDocument45 pagesProject WorkFanenter EmmanuelNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With Utilization of Malaria Preventive and Control Measures Among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinic at Kisumu County Referral Hospital in Kisumu City Western KenyaDocument22 pagesFactors Associated With Utilization of Malaria Preventive and Control Measures Among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinic at Kisumu County Referral Hospital in Kisumu City Western KenyaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Factors Contributing To Poor Compliance With Anti-Tb Treatment Among Tuberculosis PatientsDocument14 pagesFactors Contributing To Poor Compliance With Anti-Tb Treatment Among Tuberculosis PatientsAnonymous QPXAgjBwNo ratings yet

- Treating Opioid Use Disorder in General Medical SettingsFrom EverandTreating Opioid Use Disorder in General Medical SettingsSarah E. WakemanNo ratings yet

- From Research To National Expansion - 20 Years'experience of Community-Based Management of Childhood Pneumonia in NepalDocument5 pagesFrom Research To National Expansion - 20 Years'experience of Community-Based Management of Childhood Pneumonia in NepalAnil MishraNo ratings yet

- BMC Medicine: Patient-Centred Tuberculosis Treatment Delivery Under Programmatic Conditions in Tanzania: A Cohort StudyDocument10 pagesBMC Medicine: Patient-Centred Tuberculosis Treatment Delivery Under Programmatic Conditions in Tanzania: A Cohort StudyNay Lin HtikeNo ratings yet

- Art 3. Fdez-Lázaro, 2019Document12 pagesArt 3. Fdez-Lázaro, 2019Centro Estudios JovellanosNo ratings yet

- Cancer Screening in the Developing World: Case Studies and Strategies from the FieldFrom EverandCancer Screening in the Developing World: Case Studies and Strategies from the FieldMadelon L. FinkelNo ratings yet

- Burden of Tuberculosis - Combating Drug Resistance: EditorialDocument3 pagesBurden of Tuberculosis - Combating Drug Resistance: EditorialmominamalikNo ratings yet

- 2 SchistoDocument3 pages2 Schistoapi-281306164No ratings yet

- Fredrick Alleni Mfinanga and Tafuteni Nicholaus Chusi and Agnes B. ChaweneDocument6 pagesFredrick Alleni Mfinanga and Tafuteni Nicholaus Chusi and Agnes B. ChaweneinventionjournalsNo ratings yet

- Lit - Jumbam - 2020 - BMC PH - KAP of Malaria Interventions in Rural ZambiaDocument15 pagesLit - Jumbam - 2020 - BMC PH - KAP of Malaria Interventions in Rural ZambianomdeplumNo ratings yet

- 206560-Article Text-514620-1-10-20210429Document10 pages206560-Article Text-514620-1-10-20210429Odessa Fernandez DysangcoNo ratings yet

- Integrating Severe Acute Malnutrition Into The Management of Childhood Diseases at Community Level in South SudanDocument36 pagesIntegrating Severe Acute Malnutrition Into The Management of Childhood Diseases at Community Level in South Sudanmalaria_consortium100% (1)

- Malaria Updatemar 2019Document4 pagesMalaria Updatemar 2019Priya SahNo ratings yet

- Malaria Measles Mental Fam PlanningDocument5 pagesMalaria Measles Mental Fam PlanningABBEYGALE JOYHN GALANNo ratings yet

- Tulloch2015 Article PatientAndCommunityExperiencesDocument9 pagesTulloch2015 Article PatientAndCommunityExperiencesNamira Firdha KNo ratings yet

- 2014 - Zurovac - POne - Major Improvements in The Quality of Case Management in KenyaDocument11 pages2014 - Zurovac - POne - Major Improvements in The Quality of Case Management in KenyanomdeplumNo ratings yet

- 8 FiqihDocument10 pages8 FiqihAhmad Khoirul RizalNo ratings yet

- Use Only: Oral Anti-Tuberculosis Drugs: An Urgent Medication Reconciliation at Hospitals in IndonesiaDocument7 pagesUse Only: Oral Anti-Tuberculosis Drugs: An Urgent Medication Reconciliation at Hospitals in IndonesiaHeryanti PusparisaNo ratings yet

- Anti-Plasmodium Falciparum Antibodies AcquiredDocument8 pagesAnti-Plasmodium Falciparum Antibodies AcquiredderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Epi.1993.Hogh - Actatropica.classification of Clinical Falciparum Malaria and Its Use For Evaluation of Chemo Suppression in Children Under 6 in LiberiaDocument11 pagesEpi.1993.Hogh - Actatropica.classification of Clinical Falciparum Malaria and Its Use For Evaluation of Chemo Suppression in Children Under 6 in LiberiaderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Falciparum Parasitemia Was Highest (48.9%) in The 6-Month-Old Infants. The Age-Specific Hematocrit ValueDocument5 pagesFalciparum Parasitemia Was Highest (48.9%) in The 6-Month-Old Infants. The Age-Specific Hematocrit ValuederekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Epi.2002.Checchi - transRoyalSocTropMedHyg.high PF Resistance To CQ and SP in Harper Liberia Results in Vivo and Analysis of Point MutationsDocument6 pagesEpi.2002.Checchi - transRoyalSocTropMedHyg.high PF Resistance To CQ and SP in Harper Liberia Results in Vivo and Analysis of Point MutationsderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Susceptibility of Plasmodium Falciparum Different of Quinine in Vivo and Quinine Quinidine Relation Chloroquine LiberiaDocument7 pagesSusceptibility of Plasmodium Falciparum Different of Quinine in Vivo and Quinine Quinidine Relation Chloroquine LiberiaderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Epi.2009.Huerga - transRoyalSocTropMedHyg.adult and Paediatric Mortality Patterns in A Referral Hospital in Liberia 1 Year After The End of The WarDocument9 pagesEpi.2009.Huerga - transRoyalSocTropMedHyg.adult and Paediatric Mortality Patterns in A Referral Hospital in Liberia 1 Year After The End of The WarderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Plasmodiumfalciparum: Characterization Immune Malaria. II. of Anti-P. FakiparumDocument8 pagesPlasmodiumfalciparum: Characterization Immune Malaria. II. of Anti-P. FakiparumderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Epi.1983.Willcox - annalsTropMedParasitology.a Case-Control Study in Northern Liberia of PF Malaria in Haemoglobin S and B-Thalassaemia TraitsDocument8 pagesEpi.1983.Willcox - annalsTropMedParasitology.a Case-Control Study in Northern Liberia of PF Malaria in Haemoglobin S and B-Thalassaemia TraitsderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Epi.1986.Bjorkman - AnnalsTropMedParasitology.Monthly Antimalarial Chemotherapy To Children in A Holoendemic Area of LiberiaDocument14 pagesEpi.1986.Bjorkman - AnnalsTropMedParasitology.Monthly Antimalarial Chemotherapy To Children in A Holoendemic Area of LiberiaderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- DATA.2009.Liberia - Dhs.report - Liberia Malaria Indicator Survey 2009Document143 pagesDATA.2009.Liberia - Dhs.report - Liberia Malaria Indicator Survey 2009derekwwillisNo ratings yet

- DATA.2009.Liberia - dhs.KeyFindings - Liberia Malaria Indicator Survey 2009Document2 pagesDATA.2009.Liberia - dhs.KeyFindings - Liberia Malaria Indicator Survey 2009derekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Malaria JournalDocument7 pagesMalaria JournalderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Epi.1985.Bjorkman - annalsTropMedParasitology.different Malaria Control Activities in An Area of Liberia - Effects On Ma La Rio Metric ParametersDocument8 pagesEpi.1985.Bjorkman - annalsTropMedParasitology.different Malaria Control Activities in An Area of Liberia - Effects On Ma La Rio Metric ParametersderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Ay - Journalparasitology.the Susceptibility of Liberians To The Car Strain of Plasmodium VivaxDocument4 pagesAy - Journalparasitology.the Susceptibility of Liberians To The Car Strain of Plasmodium VivaxderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- EPI.2004.Williams - Socscimed.a Critical Review of Behavioral Issues Related To Malaria Control in SSA What Contributions Have Social Scientists MadeDocument23 pagesEPI.2004.Williams - Socscimed.a Critical Review of Behavioral Issues Related To Malaria Control in SSA What Contributions Have Social Scientists Madederekwwillis100% (1)

- Epi.1979.Hedman - annalsTropMedParasitology.a Pocket of Controlled Malaria in A Holoendemic Region of West AfricaDocument9 pagesEpi.1979.Hedman - annalsTropMedParasitology.a Pocket of Controlled Malaria in A Holoendemic Region of West AfricaderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Epi.1985.Jackson - Socscimed.malaria in Liberian Children and Mothers Bio Cultural Perceptions of Illness Vs Clinical Evidence of DiseaseDocument7 pagesEpi.1985.Jackson - Socscimed.malaria in Liberian Children and Mothers Bio Cultural Perceptions of Illness Vs Clinical Evidence of DiseasederekwwillisNo ratings yet

- EPI.2007.Owusu-Agyei - Malariajournal.assessing Malaria Control in The Kassena-Nankana District of Northern Ghana Through Repeated Surveys Using The RBM ToolsDocument9 pagesEPI.2007.Owusu-Agyei - Malariajournal.assessing Malaria Control in The Kassena-Nankana District of Northern Ghana Through Repeated Surveys Using The RBM ToolsderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- EPI.2008.Deressa - jrnlBiosocialSci.malaria-Related Health-Seeking Behaviour and Challenges For Care Providers in Rural Ethiopia Implications For ControlDocument21 pagesEPI.2008.Deressa - jrnlBiosocialSci.malaria-Related Health-Seeking Behaviour and Challenges For Care Providers in Rural Ethiopia Implications For ControlderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- EPI.2008.Ssekabira - Ajtmh.improved Malaria Case Management After Integrated Team-Based Training of Health Care Workers in UgandaDocument8 pagesEPI.2008.Ssekabira - Ajtmh.improved Malaria Case Management After Integrated Team-Based Training of Health Care Workers in UgandaderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- EPI.2003.Mumba - Tmih.a Piot Model To Analyse Case Management in Malaria Control ProgrammesDocument8 pagesEPI.2003.Mumba - Tmih.a Piot Model To Analyse Case Management in Malaria Control ProgrammesderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- DEC.1998.Tanner - socsciMed.treatment-Seeking Behaviour For Malaria A Typology Based On Endemicity and GenderDocument10 pagesDEC.1998.Tanner - socsciMed.treatment-Seeking Behaviour For Malaria A Typology Based On Endemicity and GenderderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- EPI.2007.Hopkins - Malariajournal.impact of Home-Based Management of Malaria On Health Outcomes in Africa A Systematic Review of The EvidenceDocument10 pagesEPI.2007.Hopkins - Malariajournal.impact of Home-Based Management of Malaria On Health Outcomes in Africa A Systematic Review of The EvidencederekwwillisNo ratings yet

- EPI.2009.Noor - Malariajournal.health Service Providers in Somalia Their Readiness To Provide Malaria Case-ManagementDocument8 pagesEPI.2009.Noor - Malariajournal.health Service Providers in Somalia Their Readiness To Provide Malaria Case-ManagementderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Econ.2008.Mueller - Malariajournal.cost Effectiveness Analysis of ITN Distribution As Part of The Togo Integrated Child Health CampaignDocument7 pagesEcon.2008.Mueller - Malariajournal.cost Effectiveness Analysis of ITN Distribution As Part of The Togo Integrated Child Health CampaignderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Econ.2007.Mustafa - Economic Cost of Malaria On Households Duringa A Transmission Season in Khartoum State SudanDocument10 pagesEcon.2007.Mustafa - Economic Cost of Malaria On Households Duringa A Transmission Season in Khartoum State SudanderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Econ.2006.Goodman - healthPolicyandPlanning.the Cost Effect of Improving Malaria Home Management Shopkeeper Training in KenyaDocument14 pagesEcon.2006.Goodman - healthPolicyandPlanning.the Cost Effect of Improving Malaria Home Management Shopkeeper Training in KenyaderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Econ.2005.Masiye - Malariajournal.the Economic Value of An Improved Mal Treatment Programme in Zambia Using Contingent ValuationDocument9 pagesEcon.2005.Masiye - Malariajournal.the Economic Value of An Improved Mal Treatment Programme in Zambia Using Contingent ValuationderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Econ.2005.Sauerborn - WTP For Hypothetical Malaria Vaccines in Rural Burkina FasoDocument5 pagesEcon.2005.Sauerborn - WTP For Hypothetical Malaria Vaccines in Rural Burkina FasoderekwwillisNo ratings yet

- Project On Hospitality Industry: Customer Relationship ManagementDocument36 pagesProject On Hospitality Industry: Customer Relationship ManagementShraddha TiwariNo ratings yet

- Romantic Criticism of Shakespearen DramaDocument202 pagesRomantic Criticism of Shakespearen DramaRafael EscobarNo ratings yet

- ACCOUNT OF STEWARDSHIP AS Vice Chancellor University of IbadanDocument269 pagesACCOUNT OF STEWARDSHIP AS Vice Chancellor University of IbadanOlanrewaju AhmedNo ratings yet

- Philippine Phoenix Surety vs. WoodworksDocument1 pagePhilippine Phoenix Surety vs. WoodworksSimon James SemillaNo ratings yet

- Cagayan Capitol Valley Vs NLRCDocument7 pagesCagayan Capitol Valley Vs NLRCvanessa_3No ratings yet

- Judgments of Adminstrative LawDocument22 pagesJudgments of Adminstrative Lawpunit gaurNo ratings yet

- 205 Radicals of Chinese Characters PDFDocument7 pages205 Radicals of Chinese Characters PDFNathan2013100% (1)

- Can God Intervene$Document245 pagesCan God Intervene$cemoara100% (1)

- Soal Paket B-To Mkks Diy 2019-2020Document17 pagesSoal Paket B-To Mkks Diy 2019-2020Boku Hero-heroNo ratings yet

- Pol Parties PDFDocument67 pagesPol Parties PDFlearnmorNo ratings yet

- Grand Boulevard Hotel Vs Genuine Labor OrganizationDocument2 pagesGrand Boulevard Hotel Vs Genuine Labor OrganizationCuddlyNo ratings yet

- (Oxford Readers) Michael Rosen - Catriona McKinnon - Jonathan Wolff - Political Thought-Oxford University Press (1999) - 15-18Document4 pages(Oxford Readers) Michael Rosen - Catriona McKinnon - Jonathan Wolff - Political Thought-Oxford University Press (1999) - 15-18jyahmedNo ratings yet

- TDA922Document2 pagesTDA922YondonjamtsBaljinnyamNo ratings yet

- TA Holdings Annual Report 2013Document100 pagesTA Holdings Annual Report 2013Kristi DuranNo ratings yet

- Translation UasDocument5 pagesTranslation UasHendrik 023No ratings yet

- First Online Counselling CutoffDocument2 pagesFirst Online Counselling CutoffJaskaranNo ratings yet

- Homicide Act 1957 Section 1 - Abolition of "Constructive Malice"Document5 pagesHomicide Act 1957 Section 1 - Abolition of "Constructive Malice"Fowzia KaraniNo ratings yet

- China Bank v. City of ManilaDocument10 pagesChina Bank v. City of ManilaCharles BusilNo ratings yet

- SOW OutlineDocument3 pagesSOW Outlineapi-3697776100% (1)

- Ronaldo FilmDocument2 pagesRonaldo Filmapi-317647938No ratings yet

- Contextual and Content Analysis of Selected Primary SourcesDocument3 pagesContextual and Content Analysis of Selected Primary SourcesJuan Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- DAP-1160 A1 Manual 1.20Document71 pagesDAP-1160 A1 Manual 1.20Cecilia FerronNo ratings yet

- Snyder, Timothy. The Reconstruction of Nations. Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999 (2003)Document384 pagesSnyder, Timothy. The Reconstruction of Nations. Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999 (2003)Ivan Grishin100% (8)

- Top 7506 SE Applicants For FB PostingDocument158 pagesTop 7506 SE Applicants For FB PostingShi Yuan ZhangNo ratings yet

- Statutory and Regulatory BodyDocument4 pagesStatutory and Regulatory BodyIzzah Nadhirah ZulkarnainNo ratings yet

- Concept Note TemplateDocument2 pagesConcept Note TemplateDHYANA_1376% (17)

- Price ReferenceDocument2 pagesPrice Referencemay ann rodriguezNo ratings yet

- C.W.stoneking Lyric BookDocument7 pagesC.W.stoneking Lyric Bookbackch9011No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan - PovertyDocument4 pagesLesson Plan - Povertyapi-315995277No ratings yet

- Digi Bill 13513651340.010360825015067633Document7 pagesDigi Bill 13513651340.010360825015067633DAVENDRAN A/L KALIAPPAN MoeNo ratings yet