Professional Documents

Culture Documents

African Music Analysis

Uploaded by

Sam IamLifted0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

347 views6 pagesAfrican Music

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentAfrican Music

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

347 views6 pagesAfrican Music Analysis

Uploaded by

Sam IamLiftedAfrican Music

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

The concept of the existence of a unique African philosophy, as

discussed by many scholars, is said to underline the Africans

thinking and perception of life, and in turn permeates all aspects of

his existence and being, be it family, work, war or creativityFor

Meki Nzewi bases his discussion of inter-rhythmic realization and the

structure and analysis of African music on this concept of African

philosophy and African musical philosophy, calling onto the concept

of co-existence and interdependence in traditional African societies,

as he talks about the relationship between simultaneous musical

motifs in an ongoing drum music.1

This idea has been contrasted by several scholars who, taking

the Universalist perspective on philosophy, argue that the notion of

an African philosophy is a ploy by Westerners to perpetuate a sense

of inferiority and difference in the mind of the African. This

orientation is made abundantly clear in Imbos Universal Definitions

of African Philosophy, where he brings to light that the objects and

methods of philosophy are universal[and consequently] what

makes African philosophy African is not that it is about some unique

African truths, concepts, or problems, but rather that it is the written

literature

of

Africans

engaged

with

universal

philosophical

problems.2 He further disagrees with Western ethnophilosophical

1 Meki Nzewi. Theoretical Content, African Music: Theoretical

Content and Creative Continuum, The Culture exponents Definition.

Oldershausen, Germany: Institut fr Didaktik Populrer Music, 1997,

pp. 36.

2 Samuel Oluoch Imbo. Universal Definitions of African Philosophy,

An Introduction to African Philosophy. New York: Rowan &Littlefield

Publishers, 1998, p. 21.

representation

of

separateness,

ethnophilosophers

currency

of

Africa

European

that

in

their

are

emphasis

basically

stereotypes[as

such]

on

trading

the

African

in

the

difference

ethnophilosophers emphasize is difference from Europe. 3

This ideation of a universal philosophy in contrast with an

African philosophy extends beyond the boundaries of social

organization and thought; it also permeates discourse in musical

systems, especially the area of music analysis. The term analysis as

used here refers to the breaking down of musical aspects and

determining how they work together and the different roles that

each aspect plays in the total sonic structure. The question that

arises from this loose definition is how does one determine the

functions and reasons for the composers (be it communal or

individual) choices of musical elements even after breaking the

whole structure down? Does this determination or analytical

methodology emanate from a universal perspective or from the

composer/musical society? And if the latter, should that be given

prominence over the universal approach?

It is incontrovertible that the ideologies of a particular period

and geography are largely imbibed into its musical systems, and as

such the compositions that are made in that time will typify the

culture and general ethos of the people and their beliefs. This goes

to reason that methodologies and concepts developed for musical

analysis will, to a large extent, be developed with particular music

3 Samuel Oluoch Imbo Op. Cit. p. 22.

systems in mind to which it should remain faithful. In extending this

idea, it is likely that this culture/period specific analytical method

could be used in analyzing music from outside cultures or later

periods, at least on a purely sonic level. The problem with this is

that it has the potential to subject other music, without a prior

written analytical method, to harsh concepts of understanding,

analysis and interpretation or misinterpretation. Further, the music

is forced to adjust to the standards of this foreign analytical aid,

sometimes loosing integral nuances peculiar to it. This is the issue

with

analyzing

African

music

with

Western

or

Universal

methodologies: you stand the risk of generalization mostly due to

inadequate knowledge of the African culture (including music

making) and an appropriation of European terminologies to preexisting concepts used on different parts of the continentthis idea

stands true for the misappropriation of the term rhythm and its

derivatives such as polyrhythm, ploymetricity and cross-rhythms by

European theorists to the perception of movement of music in time. 4

On the other hand, Universalists could easily infer (and they

do) that the conception of a thinking so specific to African music and

the Africans special point knowledge of musical elements should be

abandoned. Thus, in his Representing African Music Victor Kofi

Agawu exclaims that the truth is that, beyond local inflections

deriving from culture-bound linguistics, historical and materially

inflected expressive preferences, there is ultimately no difference

4 Meki Nzewi. Op. Cit. pp. 32-41.

between European knowledge and African Knowledgeall talk of a

distinct African mode of hearing, or of knowledge organization is a

lie.5 Agawus argument in this literature suggests that African

music scholars should leave behind the notion that African music

and its making is too special to be analyzed by other methodologies

it would seem that he seeks a sameness in analytical ideology

while Meki Nzewi seeks a more differential approach to the issue.

Again, Agawus may be acceptable because after all, music is music

and sound is sound, so why should there be variation in the hammer

that breaks its structures down?

Drawing from the above perspectives of reasoning, I am more

likely to sway to the ideals of Kofi Agawu that there is obviously no

way not to analyze African music6. My concern therefor is the

aftermath of breaking down the structure of the music, after

identifying the what component, how do you proceed to the why

component of analyses? I am of the view that even if Western

analysis makes for a better approach to the what aspect, it will

certainly lack in the approach to the why in African music. This is

the part where a contextual analyses comes to play; the part where

we try to identify the composers motives and ideologies in his

choice of musical objects and elements; the part that requires an

understanding of the philosophy of interdependence in nature and

the African composers ideals of belonging in a society, a society

5 Victor Kofi Agawu. How Not to Analyze African Music,

Representing African Music: Postcolonial Notes, Queries, Positions.

New York: Routledge, 2003, p. 180.

6 Victor Kofi Agawu. Op. Cit. p. 196.

that is reflected in his musicfor the what is in the sound while

the why is in the people and culture that make the music.

Discussions on Analyzing African music: Universal and Specific

Ideologies.

Samuel Boateng

Kent State University

Seminar In Ethnomusicology: Music of Africa

Dr. Kazadi wa Mukuna

October 23, 2014

Paper 5

Bibliography

Agawu, Victor Kofi. How Not to Analyze African Music,

Representing African Music: Postcolonial Notes, Queries,

Positions. New York: Routledge, 2003, pp. 173-198.

Imbo, Samuel Oluoch. Universal Definitions of African Philosophy,

An Introduction to African Philosophy. New York: Rowan

&Littlefield Publishers, 1998, pp. 17-26.

Meki Nzewi. Theoretical Content, African Music: Theoretical

Content and Creative Continuum, The Culture exponents

Definition. Oldershausen, Germany: Institut fr Didaktik

Populrer Music, 1997, pp. 31-58.

You might also like

- African Music As TextDocument6 pagesAfrican Music As TextSam IamLiftedNo ratings yet

- African Rhythms and How They Are LearnedDocument18 pagesAfrican Rhythms and How They Are LearnedRodrigo ZúñigaNo ratings yet

- African Musicology Towards Defining and PDFDocument9 pagesAfrican Musicology Towards Defining and PDFKelvin VenturinNo ratings yet

- Highlife Jazz Music Analysis of Felá Aníkúlápò KutiDocument18 pagesHighlife Jazz Music Analysis of Felá Aníkúlápò KutiXucuru Do Vento100% (1)

- Calypso VS SocaDocument31 pagesCalypso VS SocaAntri.An100% (1)

- Centering On African Practice in Musical Arts EducationDocument276 pagesCentering On African Practice in Musical Arts EducationNadine MondestinNo ratings yet

- The Art of Mbira: Musical Inheritance and LegacyFrom EverandThe Art of Mbira: Musical Inheritance and LegacyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Jazz Transatlantic, Volume I: The African Undercurrent in Twentieth-Century Jazz CultureFrom EverandJazz Transatlantic, Volume I: The African Undercurrent in Twentieth-Century Jazz CultureNo ratings yet

- Djembe TUTORIAL - Playing On BeatsDocument2 pagesDjembe TUTORIAL - Playing On BeatsLouis Cesar EwandeNo ratings yet

- Aka Pygmy MusicDocument6 pagesAka Pygmy MusicEloy ArósioNo ratings yet

- Djembe PDFDocument7 pagesDjembe PDFmufon100% (1)

- The Radif of Persian Classical Music Studies of Structure and Cultural Context by Bruno NettlDocument258 pagesThe Radif of Persian Classical Music Studies of Structure and Cultural Context by Bruno NettlMarco AlleviNo ratings yet

- Babatunde Olatunji - African DrummingDocument1 pageBabatunde Olatunji - African DrummingElisa PortillaNo ratings yet

- West African Drumming and Dance in North American Universities: An Ethnomusicological PerspectiveFrom EverandWest African Drumming and Dance in North American Universities: An Ethnomusicological PerspectiveRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- African Rhythms Learning Annotated BibliographyDocument14 pagesAfrican Rhythms Learning Annotated BibliographyRodrigo ZúñigaNo ratings yet

- African Songs and Drum BeatsDocument4 pagesAfrican Songs and Drum BeatsPaul LauNo ratings yet

- The Importance of African Popular Music Studies For Ghanaian/African StudentsDocument18 pagesThe Importance of African Popular Music Studies For Ghanaian/African StudentsDaniel Do AmaralNo ratings yet

- Afro-Cuban Percussion, Its Roots and Role in Popular Cuban Music BrianandersonDocument88 pagesAfro-Cuban Percussion, Its Roots and Role in Popular Cuban Music Brianandersonluis fernando ortega100% (1)

- Traditional Music of AfricaDocument12 pagesTraditional Music of AfricaAlbert Ian Casuga100% (1)

- Sevish - Rhythm and Xen - Rhythm and Xen - Notes PDFDocument9 pagesSevish - Rhythm and Xen - Rhythm and Xen - Notes PDFCat ‡100% (1)

- Performing Englishness: Identity and politics in a contemporary folk resurgenceFrom EverandPerforming Englishness: Identity and politics in a contemporary folk resurgenceNo ratings yet

- Southern Cultures: 2013 Global Southern Music Issue, Enhanced Ebook: Spring 2013 Issue, includes Music tracksFrom EverandSouthern Cultures: 2013 Global Southern Music Issue, Enhanced Ebook: Spring 2013 Issue, includes Music tracksNo ratings yet

- Musicians from a Different Shore: Asians and Asian Americans in Classical MusicFrom EverandMusicians from a Different Shore: Asians and Asian Americans in Classical MusicRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- FLP10003 Zimbabwe MbiraDocument6 pagesFLP10003 Zimbabwe MbiratazzorroNo ratings yet

- Afro-Latin Fusions Study-GuideDocument11 pagesAfro-Latin Fusions Study-GuideFrancisco Figueroa100% (3)

- The Rudiments of Highlife MusicDocument18 pagesThe Rudiments of Highlife MusicRobert RobinsonNo ratings yet

- Drums and Drummers at the Heart of Afro-Brazilian Religious RitualsDocument18 pagesDrums and Drummers at the Heart of Afro-Brazilian Religious RitualsHeitor ZaghettoNo ratings yet

- Grade 10-African InstrumentsDocument23 pagesGrade 10-African InstrumentsAtriu FortezaNo ratings yet

- Rhythmic Aspects of The AvazDocument24 pagesRhythmic Aspects of The Avazhorsemouth100% (1)

- Percussion InstrumentsDocument3 pagesPercussion InstrumentsManish PatelNo ratings yet

- Ethnomusicology: A Global Gateway to Cultural Music TraditionsDocument4 pagesEthnomusicology: A Global Gateway to Cultural Music TraditionsAndreia DuarteNo ratings yet

- African Drum in Drum Circles EnsemblesDocument12 pagesAfrican Drum in Drum Circles EnsemblesFrancisco Javier Solis OropezaNo ratings yet

- Bruno Nettl - Infant Musical Development and Primitive MusicDocument6 pagesBruno Nettl - Infant Musical Development and Primitive Music22nd Century MusicNo ratings yet

- Cheo Feliciano: Vintage Photos Courtesy Izzy Sanabria Archives / Latin NY MagazineDocument25 pagesCheo Feliciano: Vintage Photos Courtesy Izzy Sanabria Archives / Latin NY MagazineDavid Mercado MoralesNo ratings yet

- MUSIC OF Sub-Saharan AFRICA: Ghana, Congo, Zimbabwe, Uganda, Senegal-Gambia & Republic of South AfricaDocument16 pagesMUSIC OF Sub-Saharan AFRICA: Ghana, Congo, Zimbabwe, Uganda, Senegal-Gambia & Republic of South Africafrkkrf100% (3)

- Music of IndiaDocument4 pagesMusic of IndiaPhilip WainNo ratings yet

- Black Music in The Circum-Caribbean - Excerpt PDFDocument19 pagesBlack Music in The Circum-Caribbean - Excerpt PDFblehmann2883No ratings yet

- African RhythmDocument23 pagesAfrican RhythmPedro Bernardes NetoNo ratings yet

- CLAVE CONCEPTS Afro Cuban RhythmsDocument2 pagesCLAVE CONCEPTS Afro Cuban RhythmsDavid Mercado Morales100% (2)

- Comparison of Western Music and African Music: Givewell Munyaradzi, Webster ZimidziDocument3 pagesComparison of Western Music and African Music: Givewell Munyaradzi, Webster Zimidzibamiteko ayomideNo ratings yet

- Clave Matrix ContentsDocument3 pagesClave Matrix ContentsunlockingclaveNo ratings yet

- Exploring Latin RhythmsDocument59 pagesExploring Latin Rhythmsuedathiago100% (2)

- TIRIBA and Other SongsDocument8 pagesTIRIBA and Other SongskaroNo ratings yet

- Music of The African Diaspora - The Development of Calypso Music in Trinidad and TobagoDocument5 pagesMusic of The African Diaspora - The Development of Calypso Music in Trinidad and TobagoDanNo ratings yet

- Azu Etd 14181 Sip1 M PDFDocument287 pagesAzu Etd 14181 Sip1 M PDFAngelDrumsRock100% (1)

- Indian MusicDocument12 pagesIndian Musicapi-283003679No ratings yet

- Plena: La Plena Is A Genre of Music and Dance NativeDocument5 pagesPlena: La Plena Is A Genre of Music and Dance NativeBNo ratings yet

- Mbira Music & Zimbabwe's Mbube ChoirDocument10 pagesMbira Music & Zimbabwe's Mbube ChoirDavid GleasonNo ratings yet

- Agawu - Polymeter Additive Rhythm and Other Enduring MythsDocument15 pagesAgawu - Polymeter Additive Rhythm and Other Enduring MythsClaudine20100% (1)

- How Do Solos Djembe - Lesson 1Document2 pagesHow Do Solos Djembe - Lesson 14gen_2100% (1)

- African MusicDocument47 pagesAfrican MusicElaine Mae Guillermo Esposo100% (2)

- Arabic Music and Its Development Healing MusicDocument10 pagesArabic Music and Its Development Healing Musicafrospain100% (1)

- Songs of Japanese Schoolchildren During PDFDocument12 pagesSongs of Japanese Schoolchildren During PDFAbdiel Enrique Sanchez RevillaNo ratings yet

- Asafo AbstractDocument3 pagesAsafo AbstractSam IamLiftedNo ratings yet

- Brahms Sinfonia 3Document10 pagesBrahms Sinfonia 3Licenia Yaneth Perea SantosNo ratings yet

- Sweetest MelancholyDocument8 pagesSweetest MelancholySam IamLiftedNo ratings yet

- A Love SupremeDocument9 pagesA Love SupremeSam IamLifted33% (3)

- Brahms Sinfonia 3Document10 pagesBrahms Sinfonia 3Licenia Yaneth Perea SantosNo ratings yet

- EthnomusicologyDocument1 pageEthnomusicologySam IamLiftedNo ratings yet

- African MusicDocument11 pagesAfrican MusicSam IamLiftedNo ratings yet

- Anthropology of MusicDocument2 pagesAnthropology of MusicSam IamLiftedNo ratings yet

- Anthropology of MusicDocument2 pagesAnthropology of MusicSam IamLiftedNo ratings yet

- Anthropology of MusicDocument2 pagesAnthropology of MusicSam IamLiftedNo ratings yet

- Styles of Music in AfricaDocument5 pagesStyles of Music in AfricaSam IamLiftedNo ratings yet

- Motivation Theories and Techniques for Improving Employee PerformanceDocument29 pagesMotivation Theories and Techniques for Improving Employee PerformanceAbhijeet Guha100% (1)

- Dual Relationships in Group TrainingDocument16 pagesDual Relationships in Group TrainingicanhazNo ratings yet

- Define Research and Characteristics of ResearchDocument15 pagesDefine Research and Characteristics of ResearchSohil Dhruv94% (17)

- Matrix-Direct Instruction ModelDocument1 pageMatrix-Direct Instruction Modelapi-313394680No ratings yet

- Civics Lesson 2 Why Do People Form GovernmentsDocument3 pagesCivics Lesson 2 Why Do People Form Governmentsapi-252532158No ratings yet

- Communication TheoryDocument7 pagesCommunication TheorySorin50% (2)

- Traditional vs Critical Approaches to TheoryDocument28 pagesTraditional vs Critical Approaches to TheoryLiviuGrumeza100% (1)

- Learn About Health Service ProvidersDocument2 pagesLearn About Health Service ProvidersHazel Sercado Dimalanta100% (1)

- The Kolb Learning Cycle in American Board of Surgery In-Training Exam Remediation: The Accelerated Clinical Education in Surgery CourseDocument53 pagesThe Kolb Learning Cycle in American Board of Surgery In-Training Exam Remediation: The Accelerated Clinical Education in Surgery Coursevaduva_ionut_2No ratings yet

- Machiavelli's Prince IdeasDocument1 pageMachiavelli's Prince Ideasboser3No ratings yet

- Guam Curriculum Map Science Grade KDocument8 pagesGuam Curriculum Map Science Grade Kapi-286549827No ratings yet

- Trends Neural NetworksDocument3 pagesTrends Neural Networksfrancine100% (3)

- Compensation System Project ReportDocument6 pagesCompensation System Project ReportShankar SharmaNo ratings yet

- Piaget's Stages of Cognitive DevelopmentDocument9 pagesPiaget's Stages of Cognitive DevelopmentJoanna Jelawai100% (2)

- Untπma C≥ Fen-Sa‚Dn Fpyp-T°-J≥: D.El.EdDocument33 pagesUntπma C≥ Fen-Sa‚Dn Fpyp-T°-J≥: D.El.EdmujeebNo ratings yet

- A New Information ModelDocument10 pagesA New Information Modelswerlg87ezNo ratings yet

- Scientific Method: Grade 7 Summative TestDocument2 pagesScientific Method: Grade 7 Summative TestDennisNo ratings yet

- What makes a great trainerDocument22 pagesWhat makes a great trainerAmanda ChinNo ratings yet

- Nature of PhilosophyDocument15 pagesNature of PhilosophycathyNo ratings yet

- Patterns Grade 1Document5 pagesPatterns Grade 1kkgreubelNo ratings yet

- Appleby Truth About History PDFDocument6 pagesAppleby Truth About History PDFCrystal PetersonNo ratings yet

- Rogan & Kock. 2005. Methodology and Methods of Narrative AnalysisDocument23 pagesRogan & Kock. 2005. Methodology and Methods of Narrative AnalysisTMonito100% (1)

- Introduction To Artificial Intelligence Expert SystemsDocument54 pagesIntroduction To Artificial Intelligence Expert SystemsKalyan DasNo ratings yet

- The ALL NEW Don't Think of An Elephant! - Preface and IntroductionDocument6 pagesThe ALL NEW Don't Think of An Elephant! - Preface and IntroductionChelsea Green Publishing0% (1)

- Animal Conciousnes Daniel DennettDocument21 pagesAnimal Conciousnes Daniel DennettPhil sufiNo ratings yet

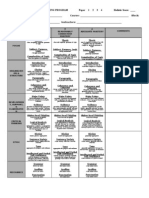

- Humanities Writing RubricDocument2 pagesHumanities Writing RubricCharles ZhaoNo ratings yet

- Service Learning ReflectionDocument6 pagesService Learning ReflectionAshley Renee JordanNo ratings yet

- Roleplaying and Motivation in TEFLDocument42 pagesRoleplaying and Motivation in TEFLGábor Szekeres100% (1)

- This Document Should Not Be Circulated Further Without Explicit Permission From The Author or ELL2 EditorsDocument8 pagesThis Document Should Not Be Circulated Further Without Explicit Permission From The Author or ELL2 EditorsSilmi Fahlatia RakhmanNo ratings yet

- IdiomsDocument2 pagesIdiomsapi-271869316No ratings yet