Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fetus Entry into Society Through Technical and Symbolic Operations

Uploaded by

bp.smith0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

69 views4 pagesExcerpt From "the Fetus and the Image War" by Luc Boltanski

Original Title

Excerpt From "the Fetus and the Image War" by Luc Boltanski

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentExcerpt From "the Fetus and the Image War" by Luc Boltanski

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

69 views4 pagesFetus Entry into Society Through Technical and Symbolic Operations

Uploaded by

bp.smithExcerpt From "the Fetus and the Image War" by Luc Boltanski

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

Luc Boltanski

"Roland Barthes" | Iconoduel | "David Freedberg"

August 23, 2005

Excerpt from "The Fetus and the Image War" by Luc Boltanski

(published in Iconoclash: Beyond the Image Wars in Science, Religion

and Art, pages 789), trans. Sarah Clift

In 1965, the photograph of an eighteen-week-old fetus enclosed in

the amniotic sac inside the womb was published on the cover of

Life magazine. Taken by Swedish phtotgrapher Lennart Nilssom,

this photograph is a milestone, and not only in the sense that it

was the product of a technological innovation. It also marks access

to the order of representation for a being who, up until then, had

evaded this order. As such, the photo prefigures the progressive

entry, some years later, of the fetus into a social order, which had

ignored it up until then, acting as if it didn't exist.

How is it then that the fetus made its entry into society? By virtue

of a series of technical, political, and symbolic operations which

imparted a weight and a presence to this practically absent being

that it had never known up until then, and through which it was

endowed with new qualities.

The work of qualification of the fetusthat conferred presence on

itwas, above all, the result of innovations which made it

accessible to the senses. With the development of medical imagery

and particularly of ultrasound, one can see the fetus in the womb,

follow its evolution, know its sex well before its birth and, in

certain cases, repair anomalies that it might be carrying. One can

also hear the beating of the heart (and record it). As well, the

development of cognitive psychology gives it capacities for

communication, capacities, which until then had not been

recognized as such. The parents are encouraged to touch it through

the abdominal wall, in a way to familiarize themselves with it and,

particularly in the case of the father, to allow him to get to know it.

The fetus has become "a someone."

However, it is not only in becoming accessible to the senses that

the fetus has entered into society in the course of the last thirty

years. Its recently acquired social presence is also the result of its

being placed at the center of two social conflicts or primary

importance, the first revolving around the conditions of its

destruction; the second around the conditions of its fabrication. In

the course of these conflicts, it acquired a new weight with regard

to practices, to techniques, to discourse, and perhaps above all, to

juridical decisions. In these conflictswhich continue up to our

timethe question of the representation of the fetus has occupied

a central place.

The first conflict was provoked by the decriminalization and then

the legalization of abortion in principle [sic] western countries.

The opponents to such measures made extensive use of the

photography of the fetus in order to support the position according

to which, to abort is to kill an unborn infant. They either used

photosthose of Nilsson or othersin order to celebrate the fetus

insofar as it represents human life in gestation, in the womb, or

they used photos of dead fetuses after abortion, often brandished

at anti-abortion demonstrations, in order to dramatize their

protest. Since from very early on, the dispute centered on the

question of knowing whether the fetus was a "person" or not, the

morphological similarity between the fetus and the infant that

would have come into the world if the fetus had survived was used

to prove that the fetus was indeed a person. Relying on the politics

of human rights, they also made the demand that the life of this

contested person be the object of protection on the part of the

State.

To counter these arguments and to reduce the emotional effects

that such photos could provoke, university academics with

affiliation to pro-choice movements (sociologists, philosophers,

jurists, historians of science, members of women's studies

departments, etc.) undertook to decode the rhetoric of the

opponents of abortion and to deconstruct the images that the latter

utilized. This endeavor led them to attempt to divest the fetus of

the presence and the status that it had recently acquired.

Academics who engaged in this undertaking made frequent use of

conceptual instruments borrowed either from the practice of

deconstruction in the literary or philisophical arena, or from the

new sociology of sciences. They took as their primary target the

realism that the users of these photos claimed as their authority

and, in so doing, adopted a constructivist position. They sought to

demonstrate that, far from being "real," these images were artifacts

and as a consequence were the instruments of an ideological

propaganda, either because they decontextualized the fetus in

isolating it from the womb (that is to say from the mother, whose

presence was excluded from the images) or because these photos

were the object of a technological coding (using electronic

microscopes and techniques of digital imagery). What is more, it

was argued that using artificial techniques in order to show that

which is normally hidden, in fact amounted to producing an

artifact.

Thus, the deconstruction of the images of the fetus triggered a

deconstruction of the fetus itself. In using elements connected to

the history of women and to the history of the sciences, these

researchers thus insisted on the "historical character" of the fetus.

Far from constituting a "natural being," eternal in its naturalness,

or a "creature of God," as affirmed, among the opponents of

abortion, who claimed religion as their authority, the fetus was,

according to these pro-choice advocates, "in fact" only "a product

of history."

More: A small index of (more or less) related textual excerpts...

"Luc Boltanski"

Posted by Dan at 01:17 AM

Comments

Referenced in this post:

Amazon: ICONOCLASH: Beyond the Image Wars in

Science, Religion and ArtBruno Latour (Editor),

Peter Weibel (Editor)

Iconoduel: Never shake thy gory locks at me (a

compendium)

You might also like

- The Dark Side of Childhood in Late Antiquity and the Middle AgesFrom EverandThe Dark Side of Childhood in Late Antiquity and the Middle AgesNo ratings yet

- From the ‘Neutral’ Body to the Postmodern Cyborg: A Critique of Gender IdeologyFrom EverandFrom the ‘Neutral’ Body to the Postmodern Cyborg: A Critique of Gender IdeologyNo ratings yet

- The Unmet Needs That Will Drive at the Progress of Civilizing The Scientific Method Applied to the Human Condition Book I: II EditionFrom EverandThe Unmet Needs That Will Drive at the Progress of Civilizing The Scientific Method Applied to the Human Condition Book I: II EditionNo ratings yet

- Gods and Monsters: The Scientific Method Applied to the Human Condition - Book IIFrom EverandGods and Monsters: The Scientific Method Applied to the Human Condition - Book IINo ratings yet

- The Efforts of Christian Religious Fundamentalists In Opposing the Teaching of Evolution In American Public SchoolsFrom EverandThe Efforts of Christian Religious Fundamentalists In Opposing the Teaching of Evolution In American Public SchoolsNo ratings yet

- Fighting for Life: Contest, Sexuality, and ConsciousnessFrom EverandFighting for Life: Contest, Sexuality, and ConsciousnessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Secret Life: Firsthand, Documented Accounts of Ufo AbductionsFrom EverandSecret Life: Firsthand, Documented Accounts of Ufo AbductionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Editorial Spring Dream Special Issue History Workshop JournalDocument7 pagesEditorial Spring Dream Special Issue History Workshop JournalfalcoboffinNo ratings yet

- The Social Direction of Evolution: An Outline of the Science of EugenicsFrom EverandThe Social Direction of Evolution: An Outline of the Science of EugenicsNo ratings yet

- From Aristotle to Darwin and Back Again: A Journey in Final Causality, Species and EvolutionFrom EverandFrom Aristotle to Darwin and Back Again: A Journey in Final Causality, Species and EvolutionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Before Head Start: The Iowa Station and America's ChildrenFrom EverandBefore Head Start: The Iowa Station and America's ChildrenNo ratings yet

- Medial Bodies between Fiction and Faction: Reinventing CorporealityFrom EverandMedial Bodies between Fiction and Faction: Reinventing CorporealityDenisa ButnaruNo ratings yet

- Neglected or Misunderstood: The Radical Feminism of Shulamith FirestoneFrom EverandNeglected or Misunderstood: The Radical Feminism of Shulamith FirestoneRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Childbirth and Authoritative Knowledge: Cross-Cultural PerspectivesFrom EverandChildbirth and Authoritative Knowledge: Cross-Cultural PerspectivesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Natal Signs: Cultural Representations of Preguancy, Birth and ParentingFrom EverandNatal Signs: Cultural Representations of Preguancy, Birth and ParentingNo ratings yet

- The Perpetual Treadmill: Encased Within the Bureaucratic Machinery of Homelessness, Mental Health, Criminal Justice and Substance Use Services Trying to Find an Exit Point.From EverandThe Perpetual Treadmill: Encased Within the Bureaucratic Machinery of Homelessness, Mental Health, Criminal Justice and Substance Use Services Trying to Find an Exit Point.No ratings yet

- Anthropology Through a Double Lens: Public and Personal Worlds in Human TheoryFrom EverandAnthropology Through a Double Lens: Public and Personal Worlds in Human TheoryNo ratings yet

- Bodily interventions and intimate labour: Understanding bioprecarityFrom EverandBodily interventions and intimate labour: Understanding bioprecarityNo ratings yet

- Human No More: Digital Subjectivities, Unhuman Subjects, and the End of AnthropologyFrom EverandHuman No More: Digital Subjectivities, Unhuman Subjects, and the End of AnthropologyRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Truth and Post-truth: Understanding the Shifting Landscape of RealityFrom EverandTruth and Post-truth: Understanding the Shifting Landscape of RealityNo ratings yet

- Biotechnology and Culture: Bodies, Anxieties, EthicsFrom EverandBiotechnology and Culture: Bodies, Anxieties, EthicsPaul E. BrodwinNo ratings yet

- Deception by Design: The Intelligent Design Movement in AmericaFrom EverandDeception by Design: The Intelligent Design Movement in AmericaNo ratings yet

- Ethical Universe: the Vectors of Evil Vs. Good: Secular Ethics for the 21St CenturyFrom EverandEthical Universe: the Vectors of Evil Vs. Good: Secular Ethics for the 21St CenturyNo ratings yet

- Neither Darwin nor Genesis: A New Paradigm for Creation and EvolutionFrom EverandNeither Darwin nor Genesis: A New Paradigm for Creation and EvolutionNo ratings yet

- Personal Reality, Volume 1: The Emergentist Concept of Science, Evolution, and CultureFrom EverandPersonal Reality, Volume 1: The Emergentist Concept of Science, Evolution, and CultureNo ratings yet

- Psychiatry and the Legacies of Eugenics: Historical Studies of Alberta and BeyondFrom EverandPsychiatry and the Legacies of Eugenics: Historical Studies of Alberta and BeyondNo ratings yet

- Leon Kass - The Wisdom of RepugnanceDocument11 pagesLeon Kass - The Wisdom of RepugnanceEvan QuenlinNo ratings yet

- The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the StateFrom EverandThe Origin of the Family, Private Property and the StateRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Laura Mulvey and Griselda Pollock discuss motherhood in feminismDocument13 pagesLaura Mulvey and Griselda Pollock discuss motherhood in feminismCarolina Del ValleNo ratings yet

- Tyrants of Matriarchy: Feminism and the Myth of Patriarchal OppressionFrom EverandTyrants of Matriarchy: Feminism and the Myth of Patriarchal OppressionRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (2)

- Transcending Scientism: Mending Broken Culture's Broken ScienceFrom EverandTranscending Scientism: Mending Broken Culture's Broken ScienceNo ratings yet

- Satyajit Ray PEP WEB ArticlesDocument23 pagesSatyajit Ray PEP WEB ArticlesheenapuNo ratings yet

- Creation or Evolution: Does It Really Matter What You BelieveFrom EverandCreation or Evolution: Does It Really Matter What You BelieveNo ratings yet

- The Social Life of SpiritsFrom EverandThe Social Life of SpiritsRuy BlanesNo ratings yet

- Who Do I Say That You Are?: Anthropology and the Theology of Theosis in the Finnish School of Tuomo MannermaaFrom EverandWho Do I Say That You Are?: Anthropology and the Theology of Theosis in the Finnish School of Tuomo MannermaaNo ratings yet

- Antebellum Posthuman: Race and Materiality in the Mid-Nineteenth CenturyFrom EverandAntebellum Posthuman: Race and Materiality in the Mid-Nineteenth CenturyNo ratings yet

- Fetal Relationality in Feminist Philosophy-An Anthropological CritiqueDocument25 pagesFetal Relationality in Feminist Philosophy-An Anthropological CritiqueanjcaicedosaNo ratings yet

- Hermann J. Muller's 1936 Letter To Stalin: University of MarylandDocument14 pagesHermann J. Muller's 1936 Letter To Stalin: University of MarylandValeri TsenkovNo ratings yet

- Deleuze and Law - Introduction PDFDocument19 pagesDeleuze and Law - Introduction PDFbp.smithNo ratings yet

- Foam CityDocument4 pagesFoam Citybp.smithNo ratings yet

- Gavin TownenDocument10 pagesGavin TownenAldoNo ratings yet

- Marneros Christos Gilles Deleuze Jurisprudence PDFDocument10 pagesMarneros Christos Gilles Deleuze Jurisprudence PDFbp.smithNo ratings yet

- Resisting PicturesDocument26 pagesResisting Picturesbp.smithNo ratings yet

- Griselda Pollock Polityka Teorii OkDocument18 pagesGriselda Pollock Polityka Teorii Okbp.smithNo ratings yet

- The Amoderns: Thoughts On An Impossible Project - AmodernDocument15 pagesThe Amoderns: Thoughts On An Impossible Project - Amodernbp.smithNo ratings yet

- Latour A Cautious Prometheus From Networks of DesignDocument27 pagesLatour A Cautious Prometheus From Networks of Designbp.smithNo ratings yet

- Regis Debray Od Medium Do MediacjiDocument7 pagesRegis Debray Od Medium Do Mediacjibp.smithNo ratings yet

- Bultmann, Rudolf - Jesus Christ and MythologyDocument34 pagesBultmann, Rudolf - Jesus Christ and MythologyFrancisco Javier B F100% (2)

- Searle Why+Should+You+Believe+It+ +John+r+SearleDocument11 pagesSearle Why+Should+You+Believe+It+ +John+r+SearleIain CowieNo ratings yet

- GLASERSFELD, Ernst Von - Key Works in Radical Constructivism PDFDocument339 pagesGLASERSFELD, Ernst Von - Key Works in Radical Constructivism PDFbp.smith100% (1)

- Bultmann, Rudolf - Jesus Christ and MythologyDocument34 pagesBultmann, Rudolf - Jesus Christ and MythologyFrancisco Javier B F100% (2)

- STENGERS Reclaiming AnimismDocument12 pagesSTENGERS Reclaiming AnimismFelipe SussekindNo ratings yet

- Review of Hybrid Thoughts in A Hybrid WorldDocument1 pageReview of Hybrid Thoughts in A Hybrid Worldbp.smithNo ratings yet

- Foam CityDocument4 pagesFoam Citybp.smithNo ratings yet

- Scientific Rationality The Sociological Turn OkDocument34 pagesScientific Rationality The Sociological Turn Okbp.smithNo ratings yet

- Interview With Bruno LatourDocument9 pagesInterview With Bruno Latourbp.smithNo ratings yet

- Editorial Observer A French Philosopher Talks Back To Hollywood and 'The Matrix' - New York TimesDocument3 pagesEditorial Observer A French Philosopher Talks Back To Hollywood and 'The Matrix' - New York Timesbp.smithNo ratings yet

- Luhmann Niklas The Reality of The Mass MediaDocument81 pagesLuhmann Niklas The Reality of The Mass MedianotizenNo ratings yet

- Scientific Rationality The Sociological Turn OkDocument34 pagesScientific Rationality The Sociological Turn Okbp.smithNo ratings yet

- Bcpc-Work-And-Financial-Plan TemplateDocument3 pagesBcpc-Work-And-Financial-Plan TemplateJeni Lagahit0% (1)

- (Advances in Political Science) David M. Olson, Michael L. Mezey - Legislatures in The Policy Process - The Dilemmas of Economic Policy - Cambridge University Press (1991)Document244 pages(Advances in Political Science) David M. Olson, Michael L. Mezey - Legislatures in The Policy Process - The Dilemmas of Economic Policy - Cambridge University Press (1991)Hendix GorrixeNo ratings yet

- America Counts On... : Scholarship Scam Spreads To Bihar, Ropes in School From Punjab TooDocument16 pagesAmerica Counts On... : Scholarship Scam Spreads To Bihar, Ropes in School From Punjab TooAnshu kumarNo ratings yet

- Using L1 in ESL Classrooms Can Benefit LearningDocument7 pagesUsing L1 in ESL Classrooms Can Benefit LearningIsabellaSabhrinaNNo ratings yet

- Safeguarding Security Gains Emphasised Ahead of ATMIS Exit From SomaliaDocument6 pagesSafeguarding Security Gains Emphasised Ahead of ATMIS Exit From SomaliaAMISOM Public Information ServicesNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2: Evolution of Urban Local Governments in IndiaDocument26 pagesChapter 2: Evolution of Urban Local Governments in IndiaNatasha GuptaNo ratings yet

- Broward Sheriffs Office Voting Trespass AgreementDocument20 pagesBroward Sheriffs Office Voting Trespass AgreementMichelle SolomonNo ratings yet

- Employee Complaint FormDocument4 pagesEmployee Complaint FormShah NidaNo ratings yet

- Philippines laws on referendum and initiativeDocument17 pagesPhilippines laws on referendum and initiativeGeorge Carmona100% (1)

- WTO PresentationDocument22 pagesWTO PresentationNaveen Kumar JvvNo ratings yet

- Mustafa Kemal Ataturk Biography: WriterDocument4 pagesMustafa Kemal Ataturk Biography: WriterGhazal KhalatbariNo ratings yet

- Jerome PPT Revamp MabiniDocument48 pagesJerome PPT Revamp Mabinijeromealteche07No ratings yet

- Jawarhalal Nehru Speeches - Vol 2Document637 pagesJawarhalal Nehru Speeches - Vol 2GautamNo ratings yet

- 154-Day Report of Registration: Political Party Registration PercentagesDocument2 pages154-Day Report of Registration: Political Party Registration PercentagesRalph CalhounNo ratings yet

- Francisco Vs Sps Gonzales Case Digest Vega-2Document2 pagesFrancisco Vs Sps Gonzales Case Digest Vega-2Iñigo Mathay Rojas100% (1)

- Mr. Asher Molk 8 Grade Social Studies Gridley Middle School: EmailDocument6 pagesMr. Asher Molk 8 Grade Social Studies Gridley Middle School: Emailapi-202529025No ratings yet

- Economics Sba UnemploymentDocument24 pagesEconomics Sba UnemploymentAndreu Lloyd67% (21)

- The Problem With Separate Toys For Girls and BoysDocument7 pagesThe Problem With Separate Toys For Girls and BoysNico DavidNo ratings yet

- Statcon - Week2 Readings 2Document142 pagesStatcon - Week2 Readings 2Kê MilanNo ratings yet

- MEA Online Appointment Receipt for Indian Passport ApplicationDocument3 pagesMEA Online Appointment Receipt for Indian Passport ApplicationGaurav PratapNo ratings yet

- Multilateralism Vs RegionalismDocument24 pagesMultilateralism Vs RegionalismRon MadrigalNo ratings yet

- Warren Harding Error - Shreyas InputsDocument2 pagesWarren Harding Error - Shreyas InputsShreyNo ratings yet

- The Forum Gazette Vol. 4 No. 20 November 1-15, 1989Document12 pagesThe Forum Gazette Vol. 4 No. 20 November 1-15, 1989SikhDigitalLibraryNo ratings yet

- 80-Madeleine HandajiDocument85 pages80-Madeleine Handajimohamed hamdanNo ratings yet

- Writing BillsDocument2 pagesWriting BillsKye GarciaNo ratings yet

- Power of US PresidentDocument3 pagesPower of US PresidentManjira KarNo ratings yet

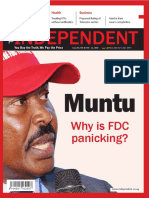

- THE INDEPENDENT Issue 541Document44 pagesTHE INDEPENDENT Issue 541The Independent MagazineNo ratings yet

- Thomas Aquinas and the Quest for the EucharistDocument17 pagesThomas Aquinas and the Quest for the EucharistGilbert KirouacNo ratings yet

- 07-17-2013 EditionDocument28 pages07-17-2013 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- The Role of The Board - Accountable Leadership ModelDocument5 pagesThe Role of The Board - Accountable Leadership Modelsagugu20004394No ratings yet