Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Uploaded by

ChicoUiobiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Uploaded by

ChicoUiobiCopyright:

Available Formats

Cost Effectiveness of Risk Management Practices

Author(s): Joan T. Schmit and Kendall Roth

Source: The Journal of Risk and Insurance, Vol. 57, No. 3 (Sep., 1990), pp. 455-470

Published by: American Risk and Insurance Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/252842 .

Accessed: 11/06/2014 17:24

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Risk and Insurance Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to The Journal of Risk and Insurance.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 200.16.5.202 on Wed, 11 Jun 2014 17:24:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

C The Journal of Risk and Insurance, 1990 Vol. LVII, No. 3, 455-470

Cost Effectiveness of Risk Management

Practices

Joan T. Schmit and Kendall Roth

Abstract

Despite the increasing importance of risk management in a successful

business organization, virtually no research has been undertaken to evaluate

the effectiveness of various risk management practices. Through analysis of

data obtained from a survey of risk management professionals, such an

evaluation has been made and is reported here. Results include the expected

effects of lower costs associated with higher levels of retention, increased size,

and less risky industries. The relationship of higher costs with the use of a

captive, and the ineffectiveness of centralization or use of analytical tools were

unexpected.

Introduction

Though how to achieve cost effectiveness of the risk management function

is an important question, it has been given relatively little attention in the

literature. The primary objective of the research presented here is to consider

that question. Specifically, the cost-effectiveness of available risk management

tools is measured while controlling for organizational risk characteristics.

Two steps are taken to meet this objective. First, the expected effectiveness

of alternate designs of the risk management function are theorized. Second,

data are analyzed to quantify how risk management functions are actualized

and to measure the relative cost effectiveness of differing risk management

designs.

Data to meet these objectives were obtained through a questionnaire sent to

risk managers of large U.S.-based corporations. No published study has.

Joan T. Schmitis AssociateProfessorat the Universityof Wisconsin-Madison.

KendallRoth

is AssistantProfessorat the Universityof South Carolina.

The authorsgratefullyacknowledgethe helpful commentsof Dan R. Anderson,NormanA.

Baglini, Anita Benedetti, Rita Epstein, and members of the Research and International

Committeesof the Risk and InsuranceManagementSociety, Inc. Executivesof CIGNA Corp.

and Johnson& Higginsalso aidedthis research.Two anonymousreviewers,the associateeditor,

and editor providedparticularlyinsightfulcomments.This researchwas funded in part by the

Internationalization

Program,Collegeof BusinessAdministration,Universityof SouthCarolina.

This content downloaded from 200.16.5.202 on Wed, 11 Jun 2014 17:24:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

456

The Journalof Risk and Insurance

attemptedto relate risk managementpracticesto cost; hence, the resultswill

contributeto the understandingof a neglectedtopic. In addition, some of the

information previouslyprovided by the Cost of Risk Survey,' is available

through this study. Thus historicalmeasuresof risk managementcosts may

help future decision-makersregardingvariouspolicy decisions.

Following a discussion of the literature,the remainderof the article is

comprised of three parts. The first is a description of the theoretical

backgroundfor the hypotheses tested with the data compiled through the

questionnaire.Next, a presentationof the resultsof the data analysisis given.

Lastly, conclusionsregardingthe resultsand discussionof futureresearchare

provided.

Literature Review

Most risk managementresearchreportedin this journal and elsewherehas

focused on whether or not the discipline should persist. Early pieces

consideredthe desirabilityof developinga specializedbusinesscurriculumfor

risk management (see, Christy, 1962; Criddle, 1963; Hammond, 1963;

Loman, 1966; Long, 1961; Mehr, 1987; and Snider, 1961). The authors

tended to agree that institutionalspecializationin risk managementgave it a

valued position in businesseducation.

Laterwork evaluatedrisk management'srole in the context of the "theory

of the firm." These efforts are exemplifiedby Mehr and Forbes (1973) who

state:

... risk managementmodels which assume away the complex and conflicting

objectivesfound withincorporationsappearto be naive.For example,whilenormative

theorymay prescribea formalmodel for makinga decisionregardingthe amountof

the insurancedeductible,such a formulationis likelyto be inapplicable,for if thereis

a conflict between internal managementand shareholderinterests (as reflected in

conflictingsolvencyand profitabilityobjectives),one can expect the interestsof the

former to call for very low deductibleswhich violate the model's rule of conduct

(p.396).

Mehr and Forbessuggest that "riskmanagementtheory needs to mergewith

traditional financial theory in order to bring added realism to the

decision-makingprocess" (p.389). Their work, in essence, foreshadowed

future finance theories, such as agency theory, and various other research

efforts such as those of Cummins(1976), Mayers and Smith (1982, 1983),

Main (1983), Doherty(1975, 1985),Smithand Buser(1987), MacMinn(1989),

Cho (1988), and others. These authors incorporate insurance and risk

'The 1985 Cost of Risk survey was a joint project conducted by the Risk and Insurance

Management Society, Inc. (RIMS) and Tillinghast Division of Towers, Perrin, Forster & Crosby

(three prior studies were sponsored by RIMS and Risk Planning Group, which has since merged

with Tillinghast). Data were gathered on insurance premiums, unreimbursed losses, risk control

costs, and administrative expenses. Because of the low response rate (13 percent in 1985), RIMS

agreed to continue the project only if at least 20 percent of the surveyed risk managers participated

in the next survey; they did not. Hence, the Cost of Risk Survey has not been continued.

This content downloaded from 200.16.5.202 on Wed, 11 Jun 2014 17:24:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Cost Effectivenessof Risk ManagementPractices

457

managementdecisionsin what Mayersand Smithterm "the moderntheoryof

finance," consideringuse of insurancealong with various debt and equity

options in making financingdecisions.

Mayers and Smith (1982) show that the corporate decision to purchase

insuranceis desirable(i.e., the risk managementfunction adds value) when

advantages in risk bearing and/or service activities accrue to insurers,

reductionsin the costs of bankruptcyare significant, contractingcosts are

minimized, and/or taxes are reduced. Meyers and Smith also show how

bondholderscan control an incentiveconflict with shareholdersby requiring

the firm to purchaseinsurance(1987). Consideringhow to maximizethe value

of the risk managementfunction, of which purchasinginsuranceis a part, is

the purposeof the presentstudy.

A numberof surveyshavebeen conductedto measurethe risk management

function.2These includeO'Connell(1975), Cerveny(1979) and Baglini(1976,

1983).3 The generalintentof surveyingrisk managersin priorstudieshas been

to measuretheir responsibilitiesand the methodsby whichthey managedrisk

under various environmentalsituations (Baglini, for example, focused on

internationalrisk management).Takinga differentapproach,the Cost of Risk

Surveysconductedby RIMS measuredrisk managementcosts attributedto

various risk managementfunctions and categorizedthem by organizational

type. The surveyused for the researchreportedhere is an amalgamationof

those types of surveys,measuringboth risk managementpracticesand costs.

TheoreticalBackgroundfor Hypotheses

Risk managementcan be describedas the performanceof activitiesdesigned

to minimizethe negativeimpact(cost) of uncertainty(risk)regardingpossible

losses. Because risk reductionis costly, minimizingthe negativeimpact will

not necessarily eliminate risk. Rather, management must decide among

alternativemethodsto balance risk and cost, and the alternativechosen will

depend upon the organization'srisk characteristics.This study measuresthe

cost-effectivenessof availablerisk managementtools whilecontrollingfor risk

characteristics.

The costs to be measured (performance)and the attributesexpected to

affect cost must now be examined.Those attributesincluderisk management

strategy regarding centralization and risk assumption; risk management

techniquesto implementthe strategychosen; and organization-specificand

general industrycharacteristicsexpected to affect strategy,implementation,

and cost.

2'ther surveyshavegenerallyfocusedon specificaspectsof risk management,such as the use

of captiveinsurers.

3Baglini'stwo surveysservedas prototypesfor the one used here. In addition, many helpful

commentswerereceivedfrom Dr. Bagliniin the preparationof the survey.

This content downloaded from 200.16.5.202 on Wed, 11 Jun 2014 17:24:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

458

The Journalof Risk and Insurance

Performance

The process of evaluatingrisk managementperformanceis complex and

difficult.4For example,decisionsto retainor transferare best evaluatedover

severalyears ratherthan annuallybecauseof the averagingeffect of random

losses. Furthermore, measurement of loss control success requires a

comparisonof expendituresfor loss control with the value of losses averted.

The value of losses not experienced,of course, is unknown.5

Defining risk management performance or "success," therefore, is a

challenge.The approachtaken hereis to defineperformanceas premiumsplus

uninsuredlosses as a percentageof total assets, hereinafterreferredto as per

unit risk managementcosts. The initial field research6pointedto this per unit

cost value as representativeof the risk manager'sresponsibilities.The risk

managercan be expectedto minimizeper unit risk managementcosts overthe

long run. Loss control and administrativeexpensesare also elementsof the

risk managementdecision-makingprocess. These expenses have not been

included here, however, because of difficulties associated with survey

responsesas discussedunderresearchmethods.

The risk managementfunction often will incorporateless tangible goals

than minimizationof explicit costs. One such goal may be maintenanceof

reputation. Furthermore,the objective of the organization's survival is

implicitin any goal undertakenby the risk manager,yieldinga tolerablelevel

of zero probabilityfor certain unsustainableevents. The authors recognize,

therefore,the potentialexistenceof organizationalobjectivesother than pure

"financialones."

Strategies

Evaluation of the cost-effectivenessof various risk managementtools is

undertakenby measuring relationshipsbetween specific risk management

strategies and risk managementperformance. Those relationshipsare the

result of two basic strategicdecisions everyrisk manageraddresses,whether

explicitly or implicitly: how much risk to assume and whether to use a

centralizedor decentralizedrisk managementprogram.

'Williams and Heins (1985) state that, "Becauserisk managersmake decisionsunderuncertainty, much of theirperformanceis difficultto evaluatein the short run."

'The problemis discussedby Mehrand Hedges(1987)on page25 as involving"intangiblecosts

and benefitswhose measureis a purelyjudgmentalmatter."

6

field researchconstituted two parts, which provided input from approximately15

insurance,brokerage,and riskmanagementexecutives.Onepartinvolvedinterviewswith brokers

and insurershavingexpertiseregardinginternationalinsuranceprograms.Theseinterviewsoffered

informationconcerningthe financingoptionsavailableto riskmanagersof international-oriented

organizations.The secondpartof the field researchwas conductedthroughRIMS'Researchand

InternationalCommittees.Membersof these committeesoffered reactionsto the surveyinstrument.

This content downloaded from 200.16.5.202 on Wed, 11 Jun 2014 17:24:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Cost Effectivenessof Risk ManagementPractices

459

Risk Retention: As a firm uses increasingamounts of retention, per unit

risk managementcosts are expectedto decline.7Becauseinsuranceincludesa

loading factor, the firm'scosts declineas the amountof coveragedeclines.Of

courseas statedearlier,in any singleyearincurredlosses may exceedexpected

losses so that insurancewould havebeen cheaperthan retention.Such a result

is assumedto be randomand ought to averageout in a cross-sectionalsample,

just as the hypothesizedrelationshipis expectedto apply overthe long run for

a single firm. Thus cross-sectionaldata addressthe preferencefor evaluating

performancein the long run, giventhat losses do not disproportionatelyaffect

a specific sample of the data. Risk assumptionmay result from retentionof

losses and/or employmentof a captiveinsurer.

Use of a Captive: Firms employingcaptive insurersare expectedto incur

lower per unit risk managementcosts than are those not using captives.

Generallythe implementationof a captiveis consideredthe most sophisticated

form of retention.A firm is expectedto use a captiveorganizationonly when

such use is cost-effective. Even when the captive's stated objective is, for

example,to obtain broadercoverageor betterterms,the ultimateresultought

to be lower overallcosts; otherwisethe broadercoveragesor improvedterms

are irrelevant.Non-riskrelatedobjectiveswere no stated by respondents.

As demonstrated by Cross, Davidson, and Thornton (1987), the

tax-deductibilityof premiumsappearsto be a significantfactor in forminga

captive. This advantagewould exist betweenpure self-insuranceand use of a

captivebut not betweencommercialinsuranceand a captive.Thus, to decide

upon formationof a captive,some cost advantagemust exist overcommercial

coverage. The captive, of course, can produce profits for the parent firm.

An assumption is made, however, that the firm can use resources more

productivelyin its chosen industrythan in investmentsof insuranceproceeds.

If not, the firm ought to switchoperationsto the investmentindustry.Hence,

despitethe omission of investmentincome and managementfees, hypothetically, the function of a captive(definedto includerisk retentiongroups)is to

reducerisk managementcosts.

Centralization: Increaseddecentralizationof the risk managementfunction

is expectedto resultin increasedper unit risk managementcosts. In addition

to deciding upon the proper level of risk assumption, risk managersmust

choose the desired degree of centralization.Business organizationsdiffer in

theirapproachesto autonomyof subsidiariesand divisions,some encouraging

significant independence,others permittinglittle individualdecision-making

authority.

From a risk managementperspective, a centralizedprogram would be

expectedto yield lowercosts. Centralizationgeneratesa varietyof advantages

includingimprovedpredictabilityof losses throughapplicationof the law of

7As noted in the literaturereview,Mayersand Smith (1982) presenta numberof benefits

attributableto the purchaseof insurance.Some of these benefitsreflectcosts not includedin the

performancemeasurediscussedhere. If included, the hypothesisrelatingperformanceto the

purchaseof insurancemay differ.

This content downloaded from 200.16.5.202 on Wed, 11 Jun 2014 17:24:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Journalof Risk and Insurance

460

dlargenumbers,availabilityof insurerpremiumcredits,and economiesof scale

for the developmentof risk managementand loss control expertise(and the

staff to supportthe expertise).In discussingthe advantagesof a centralized

program, Bradford (1988) quotes Eliot H. Pardee of Fred S. James & Co.

saying"a risk managerwho has to deal with only one brokerand one insurer

has an easier job than the buyer who must deal with several."Hence, the

administrativecosts also should be lower when managing with centralized

ratherthan decentralizedactivities.

Such advantages of centralization must be weighed against possible

disadvantages,such as inconsistencieswith the organizationalphilosophy

regardingcentralizationand possiblereductionin productivitydue to a sense

of lost autonomy.These disadvantages,however,ought not be reflectedin per

unit risk managementcosts as defined. Overall, therefore, per unit risk

managementcosts are expectedto be lowerfor centralizedthan decentralized

risk managementprograms.

Degree of Analysis

Per unit risk managementcosts are expectedto declineas the risk manager

utilizes increasingly advanced analytical techniques in making decisions.

Performancewill be affected not only by strategicdecisions,but also by the

implementationof those decisions.Risk managershaveavailablea wide range

of tools to make and executedecisions, each of which can be categorizedby

the degreeof analysisrequired.Furthermore,varioustechniquesdecidedupon

are consideredmore sophisticatedthan others.

Methods to implementrisk managementdecisions fall into a number of

categories.Decisionscan be made with little analysis,such as those based on

customor rulesof thumb. Alternatively,actions or decisionsmay be based on

extensiveanalysisconsideringexpectedloss, variance,historicaltrends,and so

on. Multiple measures are available and used in the regression analysis

discussedin the next section to assess the degreeof analysisemployedby the

firm. These include questions regardingthe firm's choice of retentionlevel

based on use of cash flow analysisand effect on earningsper shareversusthe

level of retention customarily used; the use of flow chart and financial

statementanalysis for identificationof loss exposures;and the use of risk

managementinformationsystems,loss triangles,and probablemaximumloss

estimatesfor evaluatingloss exposures.

Informationreducesthe uncertaintyof decision-making(see Tushmanand

Nadler, 1978). One would expect that the more sophisticatedthe analysis

performedby the risk manager,the more completewill be the informationon

whichdecisionsare made. Hence, a decisionbased on more advancedanalysis

would be expectedto yield betterresults.Additionally,the more advancedthe

analysis undertakenby the risk manager, the better should be his or her

position to negotiatewith insurancebrokers,and to managelocal personnel.

Because administrativeexpenses are not included in the measure of risk

management costs used here, performance will not be worsened by the

administrativeburdenof increasedanalysis.

This content downloaded from 200.16.5.202 on Wed, 11 Jun 2014 17:24:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Cost Effectivenessof Risk ManagementPractices

461

Organization-Specific and General Industry Characteristics

Risk managementcosts are expectedto be affected also by characteristicsof

the organizationand the industry.Size and risk are two such characteristics.

Size: Larger organizations are expected to have lower per unit risk

managementcosts than smallerfirms. As an organizationincreasesin size, it

can be expectedto benefitfrom advantagesof economiesof scale. Insurersare

willingto give largerorganizationsquantitydiscountsbecausetheir losses are

morepredictableand becauseadministrativecosts increaseat a decreasingrate

relativeto organizationalsize. As a result, lower per unit risk management

costs are expectedas size increases.

Risk: One of the most importantfactors likely to affect risk management

costs is the organization'srisk as definedby the industryin which it operates.

The divergence of insurance rates across industries clearly indicates this

importance. Thus organizations operating in industries with greater loss

potentialper exposureunit are expectedto havehigherrisk managementcosts

than those with smallerloss potential.

Research Methods

Questionnaire

To test the hypothesesdiscussedin the precedingpages, a questionnairewas

sent to 374 managersidentified by InstitutionalInvestor (1986) as holding

primaryresponsibilityfor risk managementfunctions in their organizations.

The companiesrepresentedby those 374 risk managersare large U.S.-based

organizations.Of the 374 risk managerssent the questionnaire,162 returned

completedsurveys,yieldinga responserate of 43 percent.

The questionnaire solicited responses regarding four topical areas:

identifyingand evaluatingexposures;decision-making;captiveinsurers;and

organizationaldata (See Appendix A for the survey questions and mean

responses).Responseswerecomprisedprimarilyof rankingsof importanceon

a scale of 1 to 5 of various risk managementactions and decisions. Data

collectedfrom the sectionsrequestingcaptiveand organizationalinformation

included premiums,losses, total assets, and retention levels. The organizational informationrepresentsaccounting,ratherthan marketdata, whichmay

have an effect on the results because of variationsin accountingrules. The

authors,however,do not perceiveany consistentbias that would influencethe

results.

A pre-test of the questionnairewas conducted with membersof RIMS'

Research and InternationalCommittees, and executivesof CIGNA Corp.,

Johnson & Higgins, and Frank B. Hall. The major modificationmade as a

result of the pre-test was to omit much of the financial data originally

requested. The reviewers cautioned that a low response rate could be

anticipatedby asking for informationconsideredproprietaryor not readily

available.Evidencefrom the 1985 Cost of Risk Survey,whereonly 50 percent

or fewerof the respondents(with an alreadylow responserate of 13 percent)

This content downloaded from 200.16.5.202 on Wed, 11 Jun 2014 17:24:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Journalof Risk and Insurance

462

answered queries regarding loss control costs and administrative expenses,

support this anticipation. Thus, questions such as the size of loss control

expenditures (a value often unavailable to the risk manager because he or she

does not have direct control of those expenditures), the amount of captive

management fees, and the extent of premiums/losses in an extended time

frame were omitted.

Research Results

Examination of Hypotheses

To test the hypotheses discussed in preceding pages, regression analysis was

performed. As previously argued, per unit risk management cost are assumed

to be a function of: the firm's retention strategy (ASSUM); the firm's

centralization strategy (CENTRL); the degree to which the firm employs

analytical tools in performing the risk management function (ANALY);

whether or not the firm uses a captive insurer (CAP); the log of the firm's size

(SIZE); and the firm's industry risk (INDCOST). Thus the regression equation

is of the following form:

FIRM COST = bo + b,ASSUM + b2CENTRL + b3ANALY +

b4CAP + b5SIZE + b6INDCOST + e

where bo represents ap intercept term, b, through b6 represent variable

coefficients, and e represents the random error term.

The dependent variable and six independent variables are defined as

follows:

FIRM COST: firm-specific ratio of premiums plus uninsured losses divided

by total assets

ASSUM:

firm-specific ratio of the summation of per occurrence

retention levels, as measured by the corporate risk manager

CENTRL: importance of local manager in choosing local retention

levels, as measured by the corporate risk manager

ANALY:

CAP:

importance of analytical tools in making risk management

decisions, as measured by the corporate risk manager (those

tools are defined in the preceding discussion of "degree of

analysis")

1 if the firm uses a captive; 0 otherwise

SIZE: log of the firm's total asset value

INDCOST: industry average of premiums plus uninsured losses divided

by total assets, as measured by the 1985 Cost of Risk Survey

(a measure of risk)

Results of the regression analysis are:

This content downloaded from 200.16.5.202 on Wed, 11 Jun 2014 17:24:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Cost Effectiveness of Risk Management Practices

463

FIRM COST = .107 - .301ASSUM + .001CENTRL - .0001ANALY

(3.39)* (-1.35)**

+ .006CAP

(1.43)**

(.093)

(-.39)

.007SIZE + .023INDCOST

(-3.56)*

(2.78)*

Valuesin parenthesesrepresentt-statistics,

* indicates significanceat the .01 level, ** indicates significanceat the .10

level.

As the t-statistics indicate, four of the six variable coefficients are

significantlydifferent from zero using a one-tailedt-test. The two variables

whose coefficientsare not significantare centralizationand degreeof analysis.

All of the coefficientsexceptthat correspondingto the captivevariableare of

the hypothesizedsign. Tolerancelevelsexceed .86 for all variables,indicating

low collinearity.Further,correlationsare .23 or lowerfor all pairedvariables,

consideredacceptablelevels. Additionally,residualplots show no consistent

pattern, supportingthe regressionassumptionsof linearityof the data and

homogeneityof variance. The adjustedR2 is .19, F = 3.792, significantat

.0026.

Interpretation of Results

From the regression analysis reported above, four of the discussed

hypothesesare supported.Two of these hypothesesconcern variablesabout

which the risk managementdepartmenthas little control: size and industry.

The other two, which relate to level of risk assumption, involve important

decisions for risk managers.

As is generallyanticipatedby risk managementprofessionals,increasesin

levels of retentionresult in lower risk managementcosts. Of course, the risk

manager must weigh the benefits of lower costs against the detrimentsof

increasedvariability.The use of captiveinsurers,in contrast,does not reduce

risk management costs, a result not anticipated by the researchers.

Centralizationand use of analyticaltools apparentlyhave no consistenteffect

on risk managementcosts.

An important aspect of these results is that advancementsin decision

making seem to have little impact on the cost effectiveness of risk

management.Severalobservationsmay help explain this phenomenon.For

example, very few organizations employ risk management information

systemsin makingdecisions. In rankingexposureevaluationmethodsfrom 1

(not important)to 5 (very important),probablemaximumloss receivedthe

highest ranking with a mean score of 4.05. Risk managementinformation

systems placed last with a mean score of 3.64. Further,cash flow analysis

(with a mean score of 3.30) is ratedlowerthan all other methodsof choosing

retentionlevelsexceptfor the levelof retentioncustomarilyused (with a mean

scoreof 2.99) and local managementdecision(witha meanscoreof 2.20). The

highestrankedmethod of choosing retentionlevelsis level of expectedlosses,

capturinga mean score of 4.42. Simple t-tests of differences among these

This content downloaded from 200.16.5.202 on Wed, 11 Jun 2014 17:24:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

464

The Journal of Risk and Insurance

meanresponsesindicatethat they are significantlydifferentas describedat the

.05 level.

These observationsprovide evidencethat risk managersgenerallyare not

using the most advancedtools as much as they are using the less advanced

tools available to them. Hence, the lack of significancein the relationship

betweencost effectivenessand degreeof analysismay stem from the absence

of any true differentiationamong risk managers.That is, degreeof analysis

may have no bearingon costs becausefew managersare using the techniques

available. A possible explanation for the relativelylow usage of advanced

techniquesis that risk managersmay be on a steep learning curve, having

advancedsignificantlyin use of analyticaltools, but not yet havingcaughtup

to the leading edge. Some evidenceof this exists in comparingthe resultsof

this researchwith that of O'Connell(1976)who found that few risk managers

wereusing quantitativetechniqueseven though they had accessto computers.

Today risk managersappearto be using quantitativetechniquesto a greater

extentthan was true in 1975;however,the availabletechniqueshave also been

elevated.

Alternativelythose who do take advantageof the advancedtechniquesmay

fall into two opposing camps. One is the high-cost group, in which risk

managersare forcedto employadvancedrisk managementtools becausetheir

firm has been hurt badly by risk management costs, perhaps especially

noticeableduringthe recent hard market (see O'Connell, 1977). The second

group is the one that uses the techniqueswell, maintaininglow costs. If the

regressionanalysisfails to account for these potentialdifferences,combining

the two groupscould yield a net effect of insignificance.

Also troublingis the non-negativesign of the captivecoefficient. Generally

a firm would be expectedto implementa captiveprogramwith the intent of

reducingcosts. Even if, as was mentionedearlier,the stated objectiveis "to

obtain broader coverage,"supposedlyobtaining that coverageis desired in

orderto reduceoverallcosts. The measureused here does omit consideration

of investmentearnings and tax effects. Furthermissing is information on

captive managementfees and risk managementdepartmentcosts. If risk

managerswere willingto providesuch data, a bettermeasureof the effect of

captiveson performancewould be available.

Resultson the impactof captivesmay be distortedsomewhatbecauseof the

sample of firms surveyed.Captivesare mainly used by the sample firms as

corporate subsidiariesrather than as industry mutuals or rent-a-captives.

These other forms of group captivesare likely to be used more frequentlyby

small and medium-sizedfirms, where economic efficiency may be more

pronounced. As pointed out by Greene (1979), a captive may meet several

organizationalobjectives. He identified four major objectives of: reducing

insurance costs, facilitating the purchase of insurance coverage, obtaining

more favorable insuranceterms and conditions, and increasingprofits on

funds held for paymentof losses (see also Baglini 1976 and 1983, and Porat

1982). Respondents of the present study also identify these objectives as

important.

This content downloaded from 200.16.5.202 on Wed, 11 Jun 2014 17:24:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Cost Effectiveness of Risk Management Practices

465

In fact, rankings of objectives for captives place "better control over

insuranceprogram"in first place and "profitpotential"in last. Perhapswith

reasoning similar to that proposed for the insignificance of analytical

techniques,those firms that choose to use a captive may be the ones with

greaterrisks and thus highercosts, such as is found in the oil and chemical

industries with regard to pollution and other difficult-to-place liability

exposures. The risk measurein this study may be insufficientlyrefined to

account for such complex differencesamong firms with regardto their loss

potential. The broad industry categories allow for wide variations among

firms in each category, thus possibly failing to account for important

idiosyncracies.

Evidencealso exists that the greaterthe extent to which captivesare used,

the better the impact on performance.The evidencederivesfrom regression

analysis of the subset of cases in which captives are used. In this smaller

sample, no dummy variable for captives is needed. Instead, the percent of

premiumspaid by the organizationwhich correspondto captive revenueis

added as an independentvariable.While not significant(perhapsbecause of

the small sample),the coefficientis negative.Whatmay be occurringis that in

some situationsthe captiveis performinga role as a statussymbol for the risk

manager, thereby causing higher risk managementcosts. In other circumstances, wherethe captiveis used extensively,the impactmay be the expected

positive effect. Alternatively,the measures used in this study to quantify

performancemay not account for the other objectives in using a captive

insurer.

Summary,Conclusions,and Areas of FutureResearch

Risk managementas a businessdisciplinehas undergoneextensivechange

over the past 25 years. New favored recognitionhas been given the field as

business executives, lawmakers,and the general public feel the effects of

volatile insurance cycles and recognize the important contribution of an

effective risk management program. Yet theoretical development and

systematic compilation of data concerning effective risk management

practiceshas been scarce.The researchreportedin this manuscriptis an effort

to fill some of that void.

A surveyof risk managementactivitiessent to risk managersof largeU.S.based organizationsprovidessome interestinginformation.For example,very

few survey respondents employ risk managementinformation systems in

makingdecisions.Further,cash flow analysisis only slightlymore important

in choosing retentionlevels than is the level of retentioncustomarilyused.

These facts may providesome insightinto the resultsof the analysisof factors

affecting risk managementcosts.

Regressionanalysiswas performedto test six hypothesesregardingvarious

factors expected to affect risk managementcosts: relative size of retention

levels, use of captive insurersor risk retentiongroups, centralizationof risk

managementactivities,degree of analysisundertakenin performingthe risk

This content downloaded from 200.16.5.202 on Wed, 11 Jun 2014 17:24:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

466

The Journalof Risk and Insurance

managementfunction, size of the organization,and industryrisk as measured

by the 1985 Cost of Risk Survey (1986). Results from the regressionanalysis

indicatethat, as expected,increasedsize, lowerindustryrisk, and higherlevels

of retention are significantly,negativelyrelated to risk managementcosts.

Captiveuse, in contrast, is associatedwith higher costs. Centralizationand

use of advanceddecision-makingtechniquesapparentlydo not haveconsistent

effects.

One possible reason for the insignificant impact of the risk manager's

analytical activities is the differing expertise of risk managers. A savvy

negotiatormay be able to obtain lowerinsurancepremiumsfor the same risk

level than a less able risk manager, regardlessof the extent of analysis

undertakenby either one. Of course, the omission of loss control data also

could be key to determiningdifferencesin effectivenessof risk management

activities.Althoughinformationis includedabout industryrisk, firms within

the same industrymay follow quite distinctloss control philosophies.

Yet anotherpossibleexplanationfor the insignificantresultsis that so little

advantageis being taken of sophisticatedrisk managementtools that none of

the firms is reapingthe benefitsavailable,i.e., no true differenceexists in the

sophisticationof the risk managers,the centralizationof the risk management

function, or the relative degree of retention. Alternatively, those risk

managers most in need of help, that is, those with relatively high risk

managementcosts, may be the managerswho are forced to use sophisticated

risk managementtechniques, including captives, as shown by O'Connell

(1977). The results may also be indicativeof the volatile insurancemarket

from 1986through 1987when data were compiled.

Whateverthe cause, results of this study provide justification for much

future research. For example, work is needed in determiningwhy risk

managershave failed to move forwardin the area of data analysis, forgoing

opportunitiesto use analyticaltechniquessuch as cash flow analysisshownto

be valuablein other settings. In conjunctionwith such information,study of

the relationship between implementation of analytical decision-making

techniquesand risk managementcosts appearswarranted.

The role of captive insurersought to be given furthercritical analysis as

well. Risk managersprovidehelpfulqualitativeinformationin explainingwhy

they use captives;yet, a criticalevaluationof the effectivenessof that decision

has not been undertaken.Whenthe riskmanagersays that captivesare used to

obtain better control over the risk managementprogram, for instance, how

does that translateinto improvedfirm performance(i.e., lower cost)? And,

how does that resultin a benefit to the organization?

In general,extendedquantitativeanalysisof the risk managementfunction

is required. Numerous texts and articles discuss the importance of risk

management. Validation of those claims through data analysis deserves

attention.

This content downloaded from 200.16.5.202 on Wed, 11 Jun 2014 17:24:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Cost Effectiveness of Risk Management Practices

467

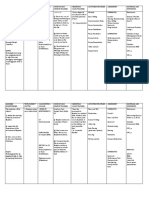

Appendix A

Survey Results

Identification

(Mean Score Rating)

How important are the following loss exposure identification techniques to your firm?

not

important

1

2

Inspection by local manager

Inspection by corporate risk mgr.

Inspection by outside expert

Risk survey or checklist

Financial statement analysis

Flow chart analysis

Internal communication, such as informal

conversation with employees

3

3.65

3.46

4.17

2.98

2.71

2.73

very

important

4

5

3.75

Evaluation

(Mean Score Rating)

How important are the following loss exposure evaluation techniques for your firm?

not

very

important

important

1

2

4

3

5

Historical loss development (loss triangles)

3.91

Frequency distributions of past losses

3.88

Probable maximum loss estimates

4.05

Maximum possible loss estimates

4.02

Expected loss analysis

3.85

Risk management information systems

3.64

Retention

(Mean Score Rating)

How important is each of the following considerations in deciding upon your firm's

level of retention?

not

very

important

important

1

2

4

3

5

Local management decision

2.20

Level of expected losses

4.42

Level of retention customarily used

2.99

Effect on earnings per share

3.73

3.39

Availability of insurer premium credit

Effect measured by cash flow analysis

3.30

This content downloaded from 200.16.5.202 on Wed, 11 Jun 2014 17:24:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

468

The Journal of Risk and Insurance

Appendix A (continued)

Captive Organizations

(Mean Score Rating)

How important are the following considerations in your firm's captive decision?

(asked only if have a captive)

not

important

2

1

Better control over insurance program

Broader (or only available coverage)

Lower expenses and/or loss costs

Profit potential

Better loss control or claims service

Improved cash flow

3

4.12

3.93

3.86

2.99

3.23

3.74

very

important

4

5

Organizational Data

Average annual premiums (captive and commercial) paid in fiscal year 1987

(in thousands of U.S. dollars)

$22,540

Average uninsured (self-insured and self-assumed) losses reported in fiscal year 1987

(in thousands of U.S. dollars)

$20.131

Average annual property and casualty premiums paid by parents to captives during

fiscal year 1987? (in thousands of U.S. dollars)

$2.701

Property

$5.705

Casualty

Number of organizations utilizing the following forms of captives

78

Corporate subsidiary

3

Rent-a-captive

30

Industry mutual (pool)

Average corporate retention (including self-insurance but excluding captives) per

occurrence in fiscal year 1987 (in thousands of U.S. dollars)

Fire & Extended Coverages

$2.313

$5.475

Earthquake

$2.564

Flood

$4.218

Premises-Operations Liability

$5,969

Products Liability

Average total assets for fiscal year 1987 (in millions of U.S. dollars).

$10.604

References

1. Baglini, Norman A., 1983, Global Risk Management: How U.S.

Corporations Manage Foreign Risk, (New York: Risk and Insurance

Management Society Publishing, Inc.).

This content downloaded from 200.16.5.202 on Wed, 11 Jun 2014 17:24:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Cost Effectivenessof Risk ManagementPractices

2.

469

1976, Risk Management in International Corporations, (New

York: Risk Studies Foundation, part of the Risk and Insurance

Management Society, Inc.).

3. Bradford, Michael, 1988, "International Market: Competition Increases

Global Plan Popularity," Business Insurance, 22:47: 3-6.

4. Cerveny, Robert P., 1979, "How Risk Managers Use Information," Risk

Management, 26:7: 10-20.

5. Cho, Dongsae, 1988, "The Impact of Risk Management Decisions on

Firm Values: Gordon's Growth Model Approach," Journal of Risk and

Insurance, 55: 118-131.

6. Christy, James, 1962, "A Risk Manager Looks at Curricular Concepts in

Risk and Insurance," Journal of Risk and Insurance, 29: 567-569.

7. Close, Darwin B., 1974, "An Organization Behavior Approach to Risk

Management," Journal of Risk and Insurance, 41: 435-450.

8. Cost of Risk Survey, 1987, (New York: Towers, Perrin, Forster & Crosby

and Risk and Insurance Management Society, Inc.).

9. Criddle, A. Hawthorne, 1963, "Risk Management," Journal of Risk and

Insurance, 30: 469-470.

10. Cross, Mark L., Wallace N. Davidson, III, and John Thornton, 1987,

"Impact of Captive Insurance Company's Formation on Firm's Value

After the Carnation Case," Journal of Business Research, 15: 329-338.

,

11.

1988, "Taxes, Stock Returns and Captive Insurance

Subsidiaries," Journal of Risk and Insurance, 55: 331-338.

12. Cummins, J. David, 1976, "Risk Management and The Theory of The

Firm," Journal of Risk and Insurance, 43: 587-609.

13. Doherty, Neil A., 1975, "Some Fundamental Theorems of Risk

Management," Journal of Risk and Insurance, 42: 447-460.

14. Doherty, Neil A., 1985, Corporate Risk Management: A Financial

Exposition, (New York: McGraw-Hill).

15. Gahin, Fikry S., 1967, "A Theory of Pure Risk Management in the

Business Firm," Journal of Risk and Insurance, 34: 121-130.

16. Greene, Mark R., 1979, "Analyzing Captives - How and What Are They

Doing?" Risk Management, 26:12: 12-20.

17. Hammond, J.D., 1963, "Risk Management," Journal of Risk and

Insurance, 30: 465-466.

18. Loman, Harry J., 1966, "The Future of Risk and Insurance as a

Collegiate Subject of Study," Journal of Risk and Insurance, 28: 55-63.

19. Long, John D., 1961, "Proposal for a New Course: Risk in the Enterprise

System," Journal of Risk and Insurance, 28: 55-63.

20. MacMinn, Richard D., 1987, "Insurance and Corporate Risk

Management," Journal of Risk and Insurance, 54: 658-677.

21. Main, Brian G., 1983, "Risk Management and The Theory of The Firm Comment," Journal of Risk and Insurance, 50: 140-144.

22. Mayers, David and Clifford W., Smith Jr., 1982, "On The Corporate

Demand for Insurance," Journal of Business, 55: 281-296.

,

This content downloaded from 200.16.5.202 on Wed, 11 Jun 2014 17:24:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

470

The Journalof Risk and Insurance

23.

, 1983, "The Independence of Individual Portfolio Decisions and

the Demand for Insurance," Journal of Political Economy, 91: 304-311.

24.

, 1987, "Corporate Insurance and The Underinvestment Problem,"

Journal of Risk and Insurance, 54: 45-54.

25. Mehr, Robert I., 1963, "Risk Management," Journal of Risk and

Insurance, 30: 466-469.

26. Mehr, Robert I., and Stephen W. Forbes, 1973, "The Risk Management

Decision in the Total Business Setting," Journal of Risk and Insurance,

40: 389-401.

27. Mehr, Robert I., and Hedges, Bob A., 1974, Risk Management Concepts

and Applications, (Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin, Inc).

28. O'Connell, John J., 1976, "Comparing Risk Management Activity in

Manufacturing Versus Service INdustries," Risk Management, 23:2:

18-25.

, 1977, "New Tools for Risk Management Research," Journal of

29.

Insurance Issues and Practices, 1: 16-20.

30. O'Connell, John J., and Jack E. Brucker, 1975, "Quantitative Techniques

and Risk Management," Risk Management, 22:5: 16-19.

31. Porat, Moshe M., 1982, "The Bermuda Captive's Organizational

Structure and Goals," Risk Management, 29:4: 32-40.

32. Skipper, Harold D., Jr., 1987, The Promotion of Risk Management in

Developing Countries, prepared for the United Nations Conference on

Trade and Development.

33. Smith, Michael, and Stephen A. Buser, 1987, "Risk Aversion, Insurance

Costs, and The Optimal Property-Liability Coverages," Journal of Risk

and Insurance, 54: 225-245.

34. Snider, H. Wayne, 1961, "Teaching Risk Management," Journal of Risk

and Insurance, 28: 41-43.

35. "The 1986 Risk Manager Directory," 1986, Institutional Investor, 20:11:

236-271.

36. Tushman, Michael L. and David A. Nadler, 1978, "Information

Processing as an Integrating Concept in Organizational Design,"

Academy of Management Review, 3: 613-624.

37. Williams, C. Arthur, and Richard M. Heins, Risk Management and

Insurance, 1989 5th ed., (New York: McGraw-Hill).

This content downloaded from 200.16.5.202 on Wed, 11 Jun 2014 17:24:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Case Study MethodologyDocument14 pagesCase Study MethodologysankofakanianNo ratings yet

- Work Employment Society-2014-Brown-112-23 PDFDocument12 pagesWork Employment Society-2014-Brown-112-23 PDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- Robert Yin Case Study ResearchDocument26 pagesRobert Yin Case Study ResearchIpshita Roy75% (16)

- 1 PB PDFDocument5 pages1 PB PDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- Chapter3 PDFDocument12 pagesChapter3 PDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of The Social Sciences-2012-Ruzzene-99-120 PDFDocument22 pagesPhilosophy of The Social Sciences-2012-Ruzzene-99-120 PDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- 00b4951e516bfa3176000000 PDFDocument19 pages00b4951e516bfa3176000000 PDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- 294 Full PDFDocument27 pages294 Full PDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- Case Studies Lecture 4-5Document13 pagesCase Studies Lecture 4-5Gricelda Berenice Armijo TorresNo ratings yet

- Turner Qualitative Interview Design 2Document7 pagesTurner Qualitative Interview Design 2Taufiq XemoNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument9 pagesPDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- StyleEase (N. D.) StyleEase For APA Style Users Guide PDFDocument83 pagesStyleEase (N. D.) StyleEase For APA Style Users Guide PDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- Software and Fieldwork Friese in Hobbs-Ch19 PDFDocument26 pagesSoftware and Fieldwork Friese in Hobbs-Ch19 PDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- Using Case Study in ResearchDocument12 pagesUsing Case Study in ResearchUsman Ali100% (1)

- PDFDocument15 pagesPDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- Martyn Hammersley - What Is Qualitative Research (2012) (A)Document136 pagesMartyn Hammersley - What Is Qualitative Research (2012) (A)KristiX1100% (2)

- 00b4952e1535012455000000 PDFDocument28 pages00b4952e1535012455000000 PDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument17 pagesPDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- Stake1995 PDFDocument20 pagesStake1995 PDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- Ejbrm Volume12 Issue1 Article335Document9 pagesEjbrm Volume12 Issue1 Article335ChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- What Is Sustainability PDFDocument13 pagesWhat Is Sustainability PDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- GP202MOOC ReservoirGeomechanics-SyllabusSpring2014Document2 pagesGP202MOOC ReservoirGeomechanics-SyllabusSpring2014doombuggyNo ratings yet

- Aerospace and Defense The Value Adding Internal Audit Function Secured PDFDocument8 pagesAerospace and Defense The Value Adding Internal Audit Function Secured PDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument24 pagesPDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument3 pagesPDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- Tariff Methodology For The Setting of Pipeline Tariffs - 5th Edition PDFDocument41 pagesTariff Methodology For The Setting of Pipeline Tariffs - 5th Edition PDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- Oil Pipeline Tariffs - 2007 - ENG PDFDocument71 pagesOil Pipeline Tariffs - 2007 - ENG PDFChicoUiobiNo ratings yet

- Arthashastra of Chanakya - EnglishDocument614 pagesArthashastra of Chanakya - EnglishHari Chandana K83% (6)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- HALPRIN Lawrence The RSVP Cycles Creative Processes in The Human EnvironmentDocument10 pagesHALPRIN Lawrence The RSVP Cycles Creative Processes in The Human EnvironmentNuno CardosoNo ratings yet

- Hetherington, Norriss - Planetary Motions A Historical Perspective (2006)Document242 pagesHetherington, Norriss - Planetary Motions A Historical Perspective (2006)rambo_style19No ratings yet

- College Graduation SpeechDocument2 pagesCollege Graduation SpeechAndre HiyungNo ratings yet

- Crisis ManagementDocument9 pagesCrisis ManagementOro PlaylistNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Children's SpiritualityDocument15 pagesInternational Journal of Children's SpiritualityМаксим КоденевNo ratings yet

- Essay For EnglishDocument3 pagesEssay For EnglishThe Darth GiraffeNo ratings yet

- Bare AnalysisDocument22 pagesBare AnalysisBrendan Egan100% (2)

- Curriculum Vitae-Col DR D S GrewalDocument13 pagesCurriculum Vitae-Col DR D S GrewalAvnish Kumar ThakurNo ratings yet

- Service BlueprintDocument10 pagesService BlueprintSam AlexanderNo ratings yet

- Future Namibia - 2nd Edition 2013 PDFDocument243 pagesFuture Namibia - 2nd Edition 2013 PDFMilton LouwNo ratings yet

- Sociological Theory: Three Sociological Perspectives: Structural FunctionalismDocument8 pagesSociological Theory: Three Sociological Perspectives: Structural FunctionalismAbdulbasit TanoliNo ratings yet

- Chinese Language Textbook Recommended AdultDocument10 pagesChinese Language Textbook Recommended Adulternids001No ratings yet

- AJaffe PPT1Document40 pagesAJaffe PPT1Thayse GuimarãesNo ratings yet

- Optimal Decision Making and The Anterior Cingulate Cortex: ArticlesDocument9 pagesOptimal Decision Making and The Anterior Cingulate Cortex: ArticlesblocheNo ratings yet

- Format of Debate: Position Paper Four Reason Why Rizal RetractedDocument3 pagesFormat of Debate: Position Paper Four Reason Why Rizal RetractedBrianPlayz100% (1)

- Chaining and Knighting TechniquesDocument3 pagesChaining and Knighting TechniquesAnaMaria100% (1)

- Ideas To Make Safety SucklessDocument12 pagesIdeas To Make Safety SucklessJose AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Chapter Ten: Organizational Culture and Ethical ValuesDocument15 pagesChapter Ten: Organizational Culture and Ethical ValuesmeekzNo ratings yet

- Letting Go of The Words: Writing E-Learning Content That Works, E-Learning Guild 2009 GatheringDocument10 pagesLetting Go of The Words: Writing E-Learning Content That Works, E-Learning Guild 2009 GatheringFernando OjamNo ratings yet

- Level 3 Health and Social Care PackDocument735 pagesLevel 3 Health and Social Care PackGeorgiana Deaconu100% (4)

- Connotative Vs Denotative Lesson Plan PDFDocument5 pagesConnotative Vs Denotative Lesson Plan PDFangiela goc-ongNo ratings yet

- Guidelines Public SpeakingDocument4 pagesGuidelines Public SpeakingRaja Letchemy Bisbanathan MalarNo ratings yet

- Avant-Garde Aesthetics and Fascist Politics Thomas Mann's Doctor Faustus and Theodor W. Adorno's Philosophy of Modern MusicDocument29 pagesAvant-Garde Aesthetics and Fascist Politics Thomas Mann's Doctor Faustus and Theodor W. Adorno's Philosophy of Modern MusicGino Canales RengifoNo ratings yet

- Patient Autonomy and RightDocument24 pagesPatient Autonomy and RightGusti Ngurah Andhika P67% (3)

- George Barna and Frank Viola Interviewed On Pagan ChristianityDocument9 pagesGeorge Barna and Frank Viola Interviewed On Pagan ChristianityFrank ViolaNo ratings yet

- Validity & RealibilityDocument13 pagesValidity & RealibilityaidilubaidillahNo ratings yet

- Jean Molino: Semiologic TripartitionDocument6 pagesJean Molino: Semiologic TripartitionRomina S. RomayNo ratings yet

- Grade 1 Syllabus 2019-2020Document15 pagesGrade 1 Syllabus 2019-2020SiiJuliusKhoNo ratings yet

- A00 Book EFSchubert Physical Foundations of Solid State DevicesDocument273 pagesA00 Book EFSchubert Physical Foundations of Solid State DevicesAhmet Emin Akosman100% (1)

- Test 16 1-10-: Vocabulary / Test 16 (60 Adet Soru) Eskişehir YesdđlDocument5 pagesTest 16 1-10-: Vocabulary / Test 16 (60 Adet Soru) Eskişehir Yesdđlonur samet özdemirNo ratings yet