Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sawmill Profile Softwood Sawmill Industry

Uploaded by

Chuck AchbergerOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sawmill Profile Softwood Sawmill Industry

Uploaded by

Chuck AchbergerCopyright:

Available Formats

SAWMILL

PRO FILE

By

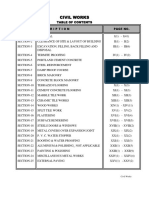

Henry Spelter & Table 1-Summary of capacity and production of U.S

Matthew Alderman

and Canadian softwood lumber sawmills, 1999 to 2005

Capacity

Mills Capacity Production utilization

New Forest Products Year (no.) (×106m3) (×106m3) (%)

Lab report defines

the makeup of North 1999 1,253 167 159 95

America's softwood 2000 1,244 172 160 93

sawmill industry. 2001 1,209 172 154 89

2002 1,154 174 161 92

2003 1,134 179 164 91

EDITOR'S NOTE: The following is

an edited version of the report, "Profile 2004 1,097 185 172 93

2005: Softwood Sawmills in the United 2005 1,067 189 - -

States and Canada,"as published by the

USDA Forest Service, Forest Products

Laboratory. Research Paper FPL-RP

630. It updates a similar "Profile 2003"

report. It will be published in three parts

Table 2-Reported capacity estimates

in Timber Processing, with the first part Capacity estimates (×106 m3)

this month on sawmill capacities, em

ployment and employee productivity. Year Profile 2001a Profile 2003b Profile 2005c

Parts two and three will cover Log Sire

and Lumber Recovery. and Economic 1995 149 149 149

Conditions and Outlook, respectively. 1996 152 152 152

The report in its entirety includes state

by-state maps with individual mill loca 1991 157 157 156

tions and capacities. 1998 162 162 161

Capacity was defined as the produc

1999 167 169 167

tion limit based on a mill's normal shift

schedule rather than a fixed number of 2000 168 173 172

shifts. Most large mills run two shifts 2001 166 173 172

daily, but many run three and others

only one. Shifts also range from the 2002 — 174 174

normal eight hours a day to nine or 10 2003 — 174 179

hours and can vary as a result of market 2004 —

conditions. Thus. the potential for phys

— 185

ical output may be higher than the num 2005 — — 189

bers reported here. This enumeration aSpelter and McKeever 2001.

also excluded small or seasonal opera

tions, as their contributions to lumber

b

Spelter and Alderman 2003.

production are mininial. c2005 data are from this report

To make data comparable, they were

30 DECEMBER 2005 TIMBER PROCEEDING

converted to common international units.

Table 3–North American softwood sawmill capacity

For lumber the researcher took board

foot volumes at face value and converted estimates, 1995 to 2005

them to cubic meters based on 424 board Capacity estimates (× 106 m3)

feet (BF) equaling I cubic meter (m3).

This ignores differences between nomi

Year United States Canada Total

nal and actual lumber sizes; thus, the

metric volumes are also nominal, not ac 1995 83 66 149

tual. Lumber recovery data presented a

bigger problem because they are reported 1996 84 67 152

in various measures of volume and 1997 87 69 156

weight in which the size of the timber af 1998 90 71 161

fects the result. Accordingly, in convert

ing the disparate units to a common 1999 92 76 167

cubic platform, the researchers had to ac 2000 94 78 172

count for the confounding effect of tim

ber size. Thus, unlike with lumber, spe 2001 92 80 172

cific rather than general conversion fac 2002 92 81 174

tors were used. 2003 96 179

83

The information in this study was

compiled from a variety of sources that 2004 99 87 185

are listed in the original report. Also 2005 101 88 189

available in the original report are the

various conversion equations and bench Annual increase (%) 2.0 2.9 2.4

marking formulas.

A

s of July 2005, the main

stream of the stofwood

lumber industry in the U.S.

Table 4–Softwood sawmill capacity by region given in

and Canada consisted of

about1,067sawmills. volume and indexed to 1999

These sawmills had a combined capacity

of 189 million m3 (80 billion BF), em

Sawmill capacity

ployed about 99,000, produced about Region 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

172 million m3 (nominal, 73 billion BF)

of lumber, and in the process consumed Volume (×106 m3)

about 280 million m3 of wood. The ca-l

pacities of these large, permanent plants U.S. South 42.7 43.9 43.8 43.9 45.0 46.4 47.0

are laid out in Table 1. Reported capacity U.S. North 5.2 5.2 4.7 4.9 4.6 4.5 4.6

estimates through the years (that are up U.S. West 43.6 45.2 43.5 43.8 46.4 48.3 49.5

dated as new information becomes avail

able) are shown in Table 2. BCa 35.9 36.6 36.8 37.7 39.2 42.1 43.5

As defined above, U.S. and Canadian Other Canada 39.7 41.1 42.8 43.8 44.1 44.5 44.3

sawmill industry capacity grew from

148.7 million m3 (63 billion BF) in Total 167.2 171.9 171.6 174.0 179.3 185.9 188.9

1995 to a projected 188.9 million m3 Indexed to 1999

(80 billion BF) in 2005 (Table 3). Ca

pacity goes where the resources is and U.S. South 1.00 1.03 1.03 1.03 1.05 1.09 1.10

grows gasted where wood is most U.S. North 1.00 1.00 0.89 0.93 0.89 0.87 0.88

abundant and wavailable. Thus, British

Columbia's capacity rose the most, in U.S. West 1.00 1.04 1.00 1.00 1.06 1.11 1.14

particular during the past two years BC 1.00 1.02 1.02 1.05 1.09 1.17 1.21

(Table 4) when large volumes of bee

Other Canada 1.00 1.03 1.08 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.11

tle-killed lodgepole pine became avail

able. Once dead, such trees have a lim Total 1.00 1.03 1.03 1.04 1.07 1.11 1.13

ited shelf life for sawing into lumber

and need to be processed within five to BC, British Columbia.

a

10 years, depending on climatic condi

tions. Several companies expanded

mills to allow greater use of this rela timber sales led many mills to close. than in nearby Oregon. Growth in the

tively short-term resource. Coastal Washington, in particular, had U.S. South was more modest but steady.

Western U.S. sawmill capacity also four big greenfield plants started with a Eastern Canadian capacity also

grew strongly within the past three fifth on the way. A major incentive for showed steady growth through 2004 but

years, recovering ground lost in the this was consistently lower timber recently plateaued. An official assess-

early 1990s when reduced government prices for the same species and grades ment of Quebec forestry determined that

TIMBER PROCESSING DECEMBER 2005 31

forests there have been overcut. New

policies will lead to a 20% cutback in

Table 5-North American softwood sawmill production harvesting over the next two years. thus

estimates by different sources dimming further growth prospects in

Eastern Canada.

Production estimates (× 106 m3) Difference Among the producing regions, only

the U.S. North showed a loss, as the

Statistics U.S. U.S. Census between U.S. closure of several large mills in Maine

Year Canada WWPAa Bureau estimates (%) was not offset by new construction.

Log shortages, intensified by competi

1995 66.1 75.0 78.0 4.0 tion for logs from mills in Canada,

1996 67.3 77.5 80.4 3.7 were reasons cited for limiting expan

sion (Table 4).

1997 69.0 81.8 83.7 2.3 Capacity data are most useful for as

1998 71.2 81.8 84.7 3.5 sessing market conditions in connection

with production figures. Production data

1999 75.6 86.4 89.8 3.9 in Canada are compiled by a govern

2000 77.8 84.9 87.7 3.3 ment statistical agency (Statistics Cana

da), whereas in the U.S. both the gov

2001 79.6 81.6 83.7 2.6 ernment (U.S. Census Bureau) and the

2002 81.3 84.6 85.8 1.5 Western Wood Products Assn.

(WWPA) gather such information.

2003 83.1 86.4 84.8 -1.8 Table 5 compares these various produc

2004 85.7 90.5 tion estimates. For most of the years,

data from the Census. which theoreti

a Western Wood Products Association. cally cover all U.S. producing sawmills,

show higher volumes than the WWPA

32 DECEMBER 2005 TIMBER PROCESSING

data. Over time, though, the differences similar movements in year-to-year initial publication, this discrepancy

have tended to decline, and in 2004 the changes, with the gap between them may disappear in the final figures.

Census estimate was lower. narrowing in recent years. Likewise, The largest systematic divergence

To investigate these production dif both estimates of Western output were occurred in the North. where WWPA

ferences, we combined them with our within capacity and showed relatively estimates relative to the Census and our

estimates of capacity to calculate ca stable relationships to each other capacity estimates have risen over

pacity utilization rates (Figures 1 to 3). through 2002. However, the prelimi time. Approximately six large mills,

For the South, both production data fit nary 2003 Census-based data fell mostly in Maine, produce most of the

within our estimates of capacity (uti abruptly. Because the Census often re lumber in the North. The reported ca

lization rates below 1) and also showed vises its estimates in the year following pacities and production volumes of

34 DECEMBER 2005 TIMBER PROCESSING

these mills have not shown the kinds of By employment

increases implied by the WWPA esti we mean only

mates. Therefore, if more production is those who are di

coming from the region, its source rectly involved in

must be smaller operations, some of procuring, pro

whose capacities we do not account cessing, adminis

for. If that is the case, however, the tering and selling

Census. which canvasses all operating wood at a site. Re

mills, should have registered these vol mote location

umes. The differences between these staffs of large

data remain to he resolved. firms, loggers and

The ratios between Statistics Canada haulers, and those

productions and our capacities are employed by other

shown in Figure 4. The production data non-lumber pro

fell below our capacity figures in each ducing facilities

year except for 1999, when production within a complex

exceeded our capacity east of the fall outside of our

Rockies definition, and we

have attempted to

EMPLOYMENT OUTPUT remove data asso

ciated with them where practical.

Our estimates of Canadian softwood

In the United States. the U.S. Bureau On that basis. we estimated employ

sawmill employment were about

of Labor Statistics (2004) tracks com ment in U.S. softwood sawmills in

49,200 in 1995 compared to 43,500 in

bined employment in sawmills, planing 2004 at 55,300 compared to 66,200 in

2004, for a decline of 12%. This com

mills (both soft- and hardwoods), and 1995. This 16% loss over the nine

pares with estimates for all sawmills

wood preservation plants. By contrast, years closely parallels the more general

from Statistics Canada of 51,900 in

the data in this report are limited to data available from the U.S. Bureau of

1995 and 45,600 in 2003, a 17% de

softwood mills only and as such com Labor Statistics, which also shows a

cline (Figure 6).

plement the U.S. Bureau of Labor 16% decline, from 119,000 to 100,000

In terms of output per employee, our

Statistics' more general data. (Figure 5)

numbers indicate about a 45% improve-

36 DECEMBER 2005 TIMBER PROCESSING

ment in the U.S. and 50% dimension mills. Howev

in Canada (Figure 7). Cana Table 6–2004 North American softwood sawmill er, studs, even though

dian labor productivity has employmentand productivity they are similar high-vol

tended to be 5% to 15% ume commodities.

higher than that of U.S. showed higher productiv

mills, and a closer look at Board Specialty & ity in the U.S. The expla

2004 productivities by type & cedar Dimension Stud Timbers unknown nation lies partly in the

of mill indicates some rea raw material, which is

sons why (Table 6). Labor U.S. smaller in boreal Canada

productivity (represented Employees 8,300 33,000 6,300 2,560 5,100 where harsh growing con

here against capacity) is ditions limit tree sizes.

(no.)

least in value-added board, Smaller logs affect

cedar, and specialty opera Capacity 3,470 29,400 6,120 1,320 1,780 throughput per log and

tions (Columns I and 5) (×106 bf/yr) labor productivity. Also,

where greater product vari many Western U.S. mills

ety and thinner pieces re Capacity per 416 891 968 516 349 sell lumber green, requir

quire more labor per unit of employee ing fewer personnel to

output. Productivity in U.S. (×106 bf/yr) handle drying. Finally,

mills was lower in both cat timber mills, which are

egories. On the other hand, Canada more prevalent in the

productivity is greatest in Employees 4,100 26,100 8,400 530 4,330 US., show about equal

dimension mills, where (no.) productivities.

production focuses on more Next month: Log Size

standardized. high-volume Capacity 2,040 25,000 6,840 250 2,520 and Lumber Recovery TP

commodities (Column 2). (×106 bf/yr)

Henry Spelter is an

Access to technology is Economist, and Matthew Al-

unhindered and spreads Capacity per 498 958 812 475 582

employee derman is an Economics As-

freely across borders, re sistant with the Forest Prod-

sulting in no statistically (×106 bf/yr) ucts Laboratory, Madison

significant differences be Wis. E-mail:

tween U.S. and Canadian hspelter@wisc.edu

38 DECEMBER 2005 TIMBER PROCESSING

Volume 30 Number 10 DECEMBER 2005

Founded in 1976 Our 31 9th Consecutive Issue

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- DIN StandardsDocument284 pagesDIN Standardsz80% (15)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Anti-Termite Measures in Buildings - Code of Practice: Indian StandardDocument26 pagesAnti-Termite Measures in Buildings - Code of Practice: Indian StandardDevesh Kumar Pandey100% (2)

- Learner Guide IRE V1Document296 pagesLearner Guide IRE V1Daniel DincaNo ratings yet

- Container ChecklistDocument1 pageContainer ChecklistMuthu Kumar100% (1)

- Engineering Materials SyllabusDocument3 pagesEngineering Materials Syllabusfaizankhan23No ratings yet

- College Forestry Natural ResourcesDocument9 pagesCollege Forestry Natural ResourcesFrancis PeritoNo ratings yet

- The Sustainment BrigadeDocument178 pagesThe Sustainment BrigadeChuck Achberger100% (2)

- Signal Soldier's GuideDocument258 pagesSignal Soldier's GuideChuck Achberger100% (3)

- A Final Report From The Special Inspector General For Iraq ReconstructionDocument184 pagesA Final Report From The Special Inspector General For Iraq ReconstructionChuck AchbergerNo ratings yet

- Long-Range Surveillance Unit OperationsDocument388 pagesLong-Range Surveillance Unit OperationsChuck Achberger100% (4)

- DOJ Kill US Citizens Justification Official 2011 NovDocument16 pagesDOJ Kill US Citizens Justification Official 2011 NovAlister William MacintyreNo ratings yet

- Special OperationsDocument34 pagesSpecial OperationsChuck Achberger100% (5)

- Field Sanitation CourseDocument238 pagesField Sanitation CourseMichael JoleschNo ratings yet

- Army - fm10 16 - General Fabric RepairDocument171 pagesArmy - fm10 16 - General Fabric RepairMeowmix100% (4)

- Warsaw Pact - Treaty of Friensdhip, Cooperation and Mutual AssistanceDocument44 pagesWarsaw Pact - Treaty of Friensdhip, Cooperation and Mutual AssistanceChuck AchbergerNo ratings yet

- The Creation of The Intelligence CommunityDocument45 pagesThe Creation of The Intelligence CommunityChuck Achberger100% (1)

- Airfield and Heliport DesignDocument539 pagesAirfield and Heliport DesignChuck Achberger100% (2)

- Underwater Ice Station ZebraDocument36 pagesUnderwater Ice Station ZebraChuck AchbergerNo ratings yet

- Wartime Statues - Instruments of Soviet ControlDocument44 pagesWartime Statues - Instruments of Soviet ControlChuck AchbergerNo ratings yet

- Soviet - Czech Invasion - Lessons Learned From The 1968 Soviet Invasion of CzechoslovakiaDocument68 pagesSoviet - Czech Invasion - Lessons Learned From The 1968 Soviet Invasion of CzechoslovakiaChuck AchbergerNo ratings yet

- Cold War Era Hard Target Analysis of Soviet and Chinese Policy and Decision Making, 1953-1973Document36 pagesCold War Era Hard Target Analysis of Soviet and Chinese Policy and Decision Making, 1953-1973Chuck AchbergerNo ratings yet

- Stories of Sacrifice and Dedication Civil Air Transport, Air AmericaDocument31 pagesStories of Sacrifice and Dedication Civil Air Transport, Air AmericaChuck Achberger100% (1)

- Intelligence in The Civil WarDocument50 pagesIntelligence in The Civil WarChuck Achberger100% (1)

- Ronald Reagan Intelligence and The Cold WarDocument39 pagesRonald Reagan Intelligence and The Cold Warkkozak99No ratings yet

- Baptism by Fire CIA Analysis of The Korean WarDocument48 pagesBaptism by Fire CIA Analysis of The Korean WarChuck AchbergerNo ratings yet

- Office of Scientific Intelligence - The Original Wizards of LangleyDocument45 pagesOffice of Scientific Intelligence - The Original Wizards of LangleyChuck Achberger100% (1)

- Impact of Water Scarcity On Egyptian National Security and On Regional Security in The Nile River BasinDocument109 pagesImpact of Water Scarcity On Egyptian National Security and On Regional Security in The Nile River BasinChuck AchbergerNo ratings yet

- CIA's Clandestine Services Histories of Civil Air TransportDocument18 pagesCIA's Clandestine Services Histories of Civil Air TransportChuck Achberger100% (2)

- OIG Report On CIA Accountability With Respect To The 9/11 AttacksDocument19 pagesOIG Report On CIA Accountability With Respect To The 9/11 AttacksTheHiddenSoldiersNo ratings yet

- CIA-Origin and EvolutionDocument24 pagesCIA-Origin and EvolutionChuck AchbergerNo ratings yet

- A City Torn Apart Building of The Berlin WallDocument52 pagesA City Torn Apart Building of The Berlin WallChuck Achberger100% (2)

- U.S. Space Programs - Civilian, Military, and CommercialDocument20 pagesU.S. Space Programs - Civilian, Military, and CommercialChuck AchbergerNo ratings yet

- A Life in Intelligence - The Richard Helms CollectionDocument48 pagesA Life in Intelligence - The Richard Helms CollectionChuck AchbergerNo ratings yet

- Air America Upholding The Airmen's BondDocument33 pagesAir America Upholding The Airmen's BondChuck Achberger100% (1)

- U.S. Use of Preemptive Military ForceDocument5 pagesU.S. Use of Preemptive Military ForceChuck AchbergerNo ratings yet

- The Praetorian StarshipDocument523 pagesThe Praetorian StarshipBob Andrepont100% (3)

- TAS 201-94 - Impact Test ProceduresDocument7 pagesTAS 201-94 - Impact Test ProceduresAndrea Nicola TurcatoNo ratings yet

- Cost Breakdown of Building A HouseDocument12 pagesCost Breakdown of Building A HouseBaguma Grace GariyoNo ratings yet

- Johnboos Commercial Price List June 2021 WebDocument96 pagesJohnboos Commercial Price List June 2021 WebDiego SánchezNo ratings yet

- Timber StructuresDocument19 pagesTimber Structuresricardo coutinhoNo ratings yet

- WoodDocument38 pagesWoodDiomar LabroNo ratings yet

- Chainsaw Milling GuideDocument15 pagesChainsaw Milling GuideBobNo ratings yet

- Esc Structural IfcDocument9 pagesEsc Structural Ifcmohamed mohsenNo ratings yet

- Technical Info PDFDocument159 pagesTechnical Info PDFEngr RakNo ratings yet

- Nisula Hakkuupäät ENG 17Document24 pagesNisula Hakkuupäät ENG 17Du McdNo ratings yet

- NATRES 2nd Set of Case DigestDocument31 pagesNATRES 2nd Set of Case DigestAnonymous yVpoM0seNo ratings yet

- Flood Resilient Architecture PDFDocument52 pagesFlood Resilient Architecture PDFanashwara.pillaiNo ratings yet

- Manufacturing Practice Lab ManualDocument59 pagesManufacturing Practice Lab ManualLeam Minz100% (1)

- Chapter 5 BT-1 (Wood)Document42 pagesChapter 5 BT-1 (Wood)Joey Guarin100% (1)

- Angle Brackets For Buildings: Complete RangeDocument6 pagesAngle Brackets For Buildings: Complete RangeKenan AvdusinovicNo ratings yet

- 2 07P01 PDFDocument28 pages2 07P01 PDFMike2322No ratings yet

- MBR - DTMR Road Furniture MRTS14Document12 pagesMBR - DTMR Road Furniture MRTS14fatherofgeorgeNo ratings yet

- Bracing Design Guide 2022Document32 pagesBracing Design Guide 2022HdhdhNo ratings yet

- 3.0 Doors and Door FramesDocument19 pages3.0 Doors and Door FramesmaxNo ratings yet

- L&T Formwork PDFDocument13 pagesL&T Formwork PDFPayel Kundu100% (1)

- Lecture 4 LawDocument29 pagesLecture 4 LawLanestosa Ernest Rey B.No ratings yet

- Twinson Composite Decking InstallationDocument17 pagesTwinson Composite Decking InstallationpbrilhanteNo ratings yet

- SHERA Board Group CatalogueDocument13 pagesSHERA Board Group CatalogueAlex GeronaNo ratings yet

- Ds07 BridgesDocument16 pagesDs07 BridgesthanguctNo ratings yet

- Khair InformationDocument18 pagesKhair InformationtinkulalNo ratings yet