Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Rasa Theory and The Darśanas

Uploaded by

K.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Rasa Theory and The Darśanas

Uploaded by

K.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiCopyright:

Available Formats

Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute

THE RASA THEORY AND THE DARANAS

Author(s): K. S. Arjunwadkar

Source: Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Vol. 65, No. 1/4 (1984), pp. 81100

Published by: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41693108 .

Accessed: 14/02/2015 16:23

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE RASA THEORY AND THE DARANAS

BY

K. S. Arjunwadkar

The Rasa-straof Bharata1has served as a fountain-headof all later

discussionson rasa. Bharata treatsof the rasa complexas a resultantof its

correlativesconsistingof some mentaland some physicalphenomena. The

mentalphenomenaare bhvas dividedintopermanent( sthyins) and visiting

( samcrins);and the physical phenomenaare the hang-onsor the objectsof

the sthyins( lambana-vibhvas), the contributories

( uddipana-vibhvas

),

and the manifestations( anubhvas) with their collaborators classed as

sttvikabhvas. They are all comradesin a joint operationoriginatingfrom

the personhousingthesthyinand extendingto theperson/objectthe sthyin

hangs on, contributed

byconditionsfavourableto thishanging-on,producing

physical,visibleeffectson rhepersonhousingthesthyinwhichmanifestthe

invisiblesthyin. The sthyins

, the vyabhicrins

, thesttvikasand theanubhvas are housed in or emanate fromthe same person; and the two types

of vibhvas are exteriorto him. This operation presentedon the stage

in the form of a drama and watched by the spectators(the rasikas)9

resultsin an experience,therasa, whichtherasikasrelishand cherish.Bharata

comparesthisprocesswiththatof the preparationof food with ingredients

of different

tastes- rasas - relishedby theeater,2which,incidentally,

indicates

the source from which the term rasa is borrowed. While detailing this

apparatusof the rasa, Bharata enumerateseight( nine, as viewedby some )

to eight( or nine) sthyins

rasas corresponding

and

, thirty-three

vyabhicrins

He

:

the

sttvikas.

also

divides

as

rasas

into

two

four

causes

eight

groups

of the remainingfour. What Bharata expounded as relatingto drama is

extended to poetryand other arts. The rasa theory,therefore,formsthe

nucleusof the aestheticdeliberationsin Sanskritthroughcenturies.

From the outlineof Bharata's rasa theory,it is evidentthatit is original in most of the concepts,theirclassificationand the metalanguagehe uses

to expound it. No work in the Sanskritliterature,

or priorto

contemporary

the Ntyasstra of Bharata, attemptstreatment

of similartopicsin a way or

1

8 t SSRI: ' 3^1?- 3WI|

I Ntyasstra,VI, betweenverse31and 32.

loc.C(.

Il [ Annals BORI ]

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

82

Annals BORI , LXV ( 1984 )

by a methodcomparableto thatof Bharata. The creditdoes not, of course,

go to Bharata alone but is sharedbyhimwithhis predecessorson the subject

whomhe has frequentlyquoted. As a probable source a referencemay be

made to workson Ayurvedawhich,while treatingof their materiamedica,

speak of the rasa, vrya, vipka and prabhva of thematerialdescribed.3

One would expect an analysis of the facultiesof mind in the Yoga System

which Bharata mighthave made use of ; but littleis foundin thatsystem

whichhas even a remoteresemblancewithwhatBharata has presented. The

Smkhyasystem,akin to the Yoga, says littledifferentfromits sister-system

on thiscount. Even Kmasutra, havingratias its special field,disappointed

me in myattemptsto finda likenessof Bharata's analysisof mentalfaculties.

Surprisingly

enough,- and it may be a pure coincidence,- thereis a striking

resemblancebetween Bharata's theory of rasa and Carvaka's theory of

caitanya- consciousness,a qualityof thebody not presentindividuallyin the

four elements- theearth, the water, the fireand the air that combine to

make thebody but evolvingfromcombinationthereof.4 The same may be

said of rasa and its correlatives.

detailedso faras its mechanismis concerned,

This theory,sufficiently

which

generationsof critics offeredto solve in theirown

presentedproblems

are

The

varied, inter-relatedand so perplexingthat, even

right.

problems

afterlong discussions,the only satisfactionone is likelyto deriveis thatfor

almost every question there is a counter-question. And above all, anjr

solution has to be reconciled with what Bharata mightor mightnot have

said hereor elsewhere. If thecriticsweregiventhe choice of pickingup the

bestradical of Bharataand keepingconsistentwithit withoutany responsi^

bilityof defendinghis stand elsewhere,one feels hopeful that something

discussionsof the

morecoherentwould have come out of the hair-splitting

commentators.

The problemsstart with the very fundamentalquestionas to where

does rasa abide - in the character,in the actor or in the spectator? Every

one of thesealternativeshas its own difficulties.This breeds the next question : What is the nature of the experiencethat is called the rasa ? Is it

inference

or'perceptionor somethingelse ? This questioninevitablyleads to

the determinationof the relationof the sthayin withthe rasa. Are they

? And how does Bharata forgetto make a referenceto

identicalor different

3 Astahga-hrdaya

Sutra.1. 14etc.

4 Cp. 3^ xRnfi;

I

^4: m

lcTWt

I

i Sarva-darsana-samgraha

, Crvka.

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RJUNWADKAR: The Rasa Theoryand theDaranas

83

thesthyyinin his famousrasa-stra? What relation does rasa have with

its correlatives? What is the outcomeof rasa experience: all pleasureand no

pain, or pleasure from some rasas and pain from others? If pain is the

outcome of some rasa, how is the connoisseur interestedin it? These are

the basic questionson which criticshave wrangled for centuries. Not all

criticshave attemptedall questions. They probably presumed,as was the

examinationsome years back, that they had

practicein a higher university

to attemptc not more thanthree/four questions' ! We have then no way

but to value theiranswers' collectively* as was also the practiceof the examinersthatwenthand in hand withthe not more than' allowance.

The earliestcandidate on record who appeared for this exam was

Lollata who preferedto seek aid from his common sense rather than from

any established dogma. For him, rasa, which is substantiallythe sthyin

createdby the vibhvas,revealedby anubhvasand nourishedby the vyabhicrinsyabided primarilyin the characterin the play like Rma, and secondarilyin the actor who enacted the character.5 His outlook will be clear

whenwe imaginea flowerwhicheventuallywithersaway givingrise to a tiny

fruitthatdevelopsand ripens underfavorable nutritiveand climatic conditions.

This explanation,simpleas it sounds, createsmoreproblems than it

solves. It is not a fact with all sthyyinsthat they are nourished as the

timeadvances. Sthyins like anger and surprisewane with the time. They

would never reach the stage of rasa if we accept Lollata's explanation.

Rama is not,then,to any reasonable degree,let alone theprimary,the receptacle of rasa. Nourishmentof a sthyinlike rati is possiblein the real Rama

at the sightof the real Sta, both of whom are no more at the time of the

stagingof a play. All talk of the production,revelationand nourishmentof

therasa as Lollata visualisesit is, like thatof the fruitof a treebeyondthe

reach of a consumer,puerile.

For ankukawho thusfindsfaultwithLollata's view,the actorhimself,

of the spectatorsand is not far removed from them

is

who contemporary

Rama

whomhe imitates,is the receptacleof rasa, which

as are characterslike

is an imitationof the sthyinin the real character like Rama. This

sthyinin the actoris a matterof inferencearrivedat from his acting. Both

the sthyinand its correlativesare thus unreal and hence are named by

8 ifa

w- 1

i

^Ner; i H

Abhinv

abfioration the Rasa-stra,Page 124 in Rasa referred

to as Kang,

bhvavicraby Prof.R. P. Kangle,Bombay,1973,hereafter

followed

bypagenumbers.

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Annals BORI , LXV ( 1984)

84

Bharata by artificialtermslike vibhva

.6 How can such an unreal apparatus

lead to a real enjoymentof a rasa ? - *As does the pictureof a horse lead to

thecognitionof a real horse,' ( citra~turaga-nyya

)7 says akuka; deems

' and

it ' samvadi-bhrama

quotes Dharmakirti,the Buddhistphilosopher,as a

support.Imaginea personwho sees raysof lightat a distance, thinksthatit

is a jewel, rushesto secureit, reachesthe spot and, to his disappointment,

finds a lamp there. Imagine also anotherpersonwho sees rays of a jewel

( and not thejewel ifself,it being too small and too farfromhim), thinks

that it is a jewel,similarlyreachesthe spot and findsa jewel. In fact, both

are mistakeninasmuchas theytake as a jewel somethingotherthan a jewel.

But thisfalseknowledge( bhrama) producesa real action in them,withthe

only differencethat one of the two is rewarded with what he sought

) whilethe otheris not ( visamvdi-bhrama

( samvadi-bhrama

).8

This is how akuka argues, conceding that the inferredsthyin in

the actor and its apparatusare unreal. Personallyhe thinksthatthe cognition of the sthyinin theactor defiesdefinition,cannot be includedin any of

the knownvarietiesof cognition,but, at the same time, cannot be denied as

it is a matterof first-hand

experienceforeveryrasi/ca.9

It is customaryto deem akuka a Naiyyika on the strengthof his

view that rasa, thatis the sthyinimitated,is inferred. I do not subscribe

to thisview; for Nyya is a systemwhich expounds in detail all the four

means of knowledge of which inferenceis one, and nothingtypicalof the

Nyya systemis involvedin this view. A farmerdoes not need to study

Nyya to inferthatit would rain beforelong when he sees heavyclouds in

is adequate to deemhima Naiyyika,

the sky.If akuka's theoryof inference

6 3C-IR...

srdtaftw:

p-rrt

xT

f:| Kaiig.129-30

7 Thisexpression,

intheAbhinavabhrati

buthinted

at bysomeotherwords

missing

of a horse) usedbyAbhinava

on( Kang.145), is first

further

found

( a cow,instead

in hisKvyapraksa( UllsaIV ), whilerepresenting

used by Mammata

SaskukaV

view. 0/>.cit.p. 134.

8

I

Pramana-varttika

, 2.57.

c

view by thewords

Thisis alludedto in Sankuka's

'

Kang.130.

9 srfnicr

H ft*

T

i

gFqi

Il Kang.130.

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

: The Rasa Theoryand theDaranas

RJUNWADKAR

85

his referenceto Dharmakirtican be regardeda sufficient

groundto deemhim

a Buddhist! I wouldconsiderthesecondclaimas more plausible,as theverse

quoted fromDharmakirtiis closelyrelatedto thetheoryof knowledgeof the

Buddhistswho denythe existenceof theobjective world. This sortof n'ive

taggingon a flimsygroundwould be of littleconsequencein a seriousstudy.

akuka is attackedforholdingthisviewby both BhattaTauta and his

'

disciple, Abhinavagupta. You call rasa an imitation; okay. But from

whose pointof view ? From thatof the spectatoror of the actor? ' interro*

gates Tauta, and bringsout the fallacy in akuka's stand fromeach of

them. To know somethingas imitation,the audience must know the imitated. (Just as to appreciatea parody,you must know the original.) Bat

none has seen a characterlike the real Rma.10 Aid even if it were not a

characterlike Rma farremovedin time fromthe spectator,cognition of

imitationis possibleonlyof thingsperceptible,and not of a sthyinwhichis

beyondthe reach of sense-organsand is onlyinferred. And even as inferred,

thesthyinis cognized as a sthyinand not as an imitationof a sthyin.It is

ridiculousto believethatan imitationof the hetu( smoke-likemist) leads to

the inferenceof an imitationof thesdhya( fire-like

flowerJ.11The imitation

theorydoes not hold good even fromthe pointof view of the actor who has

not seen the real Rma; and a sthyinin anotherperson is as imperceptible

to theactor as to the spectator. How can and would an actor imitatethe

sorrowof Rma ? Rma was sorry; the actor is not. The actor can at his

best shed tearsas did Rma when he was sorry. But shedding tears is not

the same as beingsorry. And how can sheddingtears, whichis common to

all normalpeople includingtheactor when theyare sorry,be an imitationof

Rma alone ?12 Needless to say that akuka's analogy of the horse in a

pictureis beside the point, as both the imitationand the imitatedin this

case are perceptible. Moreover, a pictureis createdby means of colours;

a sthyin,which already exists, is only revealed,never created. While

akuka's theorythatthe cognitionof thesthyinin the actor

controverting

defies definition,Tauta introducesan importantidea that what we see as

Rma in a play is Rma the general,and not Rma the particular; and this

is corroboratedwhen an actor enacting Rma is substitutedby another

withoutany problemto the spectator.13

10

^ K<KIMld*rcr:

I 1 =3RPIlt

Il Kang.135.

"

137.

I Kang.

it inq

W igsiRftffel

12 ^

i

rarfq

' ... q q*

2

^iirfq u)

?fcr

dRd'T%ft.

i Rang.142.

18

^sqfirfct

I

I Kang.140.

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ArmaisBORI, LXV ( 984 )

86

Followingin the footstepsof his preceptor,Abhinavagupta picks up

more

holes in the theory offeredby Sakuka. Imitation by its very

spme

nature,arguesAbbinava, breedslaughter ( as, forinstance,does a parody)

among thethirdpartyspectators,and angeramong those thatare imitated.14

Drama can neverbe an imitation; forimitationis a relationthat can exist:

between two particularentities. When it is clear that the actor cannot

imitatethe real Rma, the only alternativeleftis thathe makesactions that

all normalpeople do under comparable conditions. If this is imitation,we

arriveat the funnyconclusionthatthe actor is imitatinghimself! In other

words,what is generalcannot be regarded as imitation.16What is drama,

that is a repeat experience,

then? It is a kind of anuvyavasya

; re-cognition

a typicalawarenessof a cognitionin whicha spectatorrevels.

akuka thusstandsdiscredited.The nextcriticis BhattaNyaka, the

authorof Hrdaya-darpana( now lost, and knownthroughquotations), which

attemptsto refute nandavardhana's theory of dhvani. Nyaka should,

chronologically,figureafter nandavardhana whose explanationof rasa is

upheld by Abhinava. But Nyaka is usheredin by Abbinava, forhis view

is finallyto be refutedby himand the view of nanda-Abhinavaschool to be

. Nyaka startswith the denial of rasa as an

introducedas the siddhnta

of

object cognition,productionor suggestion( as Ananda-Abhinava claim ).

Is it thespectatoror thecharacterlike Rma thatis the receptacleof rasa ?

Ia thefirstalternative,the spectatorwould have to be sorrywhenhe cognizes

pathos,and would not care to have the same experienceagain; forwho would

like to be sorryifone can help it? But he is not,forhe is in no way relatedto

Sita whoseseparation mightmake himsorry. He is likelyto be sorryif he

iffina similarcondition. But, what ifhe is not, and if he has his beloved by

his side while watchingthe play? He is likely tobe sorryifhe identifies

himselfwith

himselfwithRma. But how can an ordinarypersonidentify

such superhumanpersonalitiesas Rma? In the second alternative,thatis,

if'Rrnais the receptacleof rasa, is the spectator'scognitionof rasa of the

? All theseoptionswhich

natureof memory,verbal knowledgeor inference

implyany indirectcognitionof rasa militateagainstthe spectator'sexperience

that he is having a direct experienceof rasa. If a rasa like rngrais

cognized by the spectatoras based in other persons,would he not feel

14

sfsci

... PTCFlFlt

5

^rcyTfo(4

(GaekwarSeries1936)! 107.

^ ^

SWFWHfWI

afe

sfi;

Wlffl;;

A

bhinavabhrati

I

cmTHtyasstra

I toc, cit*

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Arjunwadkar

: The Rasa Theoryand theDaranas

embarrassedto watcha man and a woman in privacy, provided,of course,

he is a gentleman?16

Nyaka would, therefore,like to explain rata as a joint outcomeof

two operations- ' bhvakatva9 and ' bhojakatva' By thefirsthe means the

'

'

process of sdhrarilkarana or generalisation,i.e. shearingrasa and its

correlativesof theirparticularspace-time-person

context and making them

a ' commonwealth* - a stateproducedbyfourfoldactingin a play and gunlamkras in poetry. Thus generalisedrasa is relishedby the spectatorby

bhojakatva, a unique processof the minddistinctfromthe commonlyrecognised meansof cognitionsuch as perception,memoryand others. Though

made up of threeprimeval qualities, the Sattva, the Rajas and the Tamas,

it is dominatedby the Sattva, as a result of which this experiencerests in

the consciousness( caitanya) full of light and happiness, - muchthe same

way as in the realization of the Supreme Brahman( Para-Brahmsvda

savidha). Nyaka conceivesbhvakatvaand bhojakatvaas processes exclusively operating in the field of poetry( and drama) and distinctfromthe

abhidhprocesswhichis commonto poetryand otherliterature,17mandatory

( Veda etc.) and advisory ( Itihsa, Purna etc.).18 The chief purpose of

poetryis, therefore,

purejoy, and, onlysecondarily,didactic.

Even a hurriedsurveyof Nayaka's view would revealthatin formulating his theoryhe has drawn substantiallyon Mmms ( as Abhinava

understandshim), Smkhya and, most of all, Vednta, and exemplifies

whatan imaginative,discriminating

man of wide knowledgecan contribute

to the expositionof a theory. For his bhvakatvaconcept, he is indebtedto

Mimmsa ( as Abhinava understandshim); for the constitutionof the rasa

experience,to Samkhya{ also absorbed in Vednta); and fortheidea of overwhelming,total absorptionin the experience,to Vednta.Nyaka is the fist

18 # *

SRfact,

I

flfspq

^

f| Tif

f|

srfi

RSwaf wraj ... qw g srltr

Kang.147.

is 5i5^5in=ri?qqri^l

TR

^Tfff

WT. | ^ ^

i

^

Kang.147.

sqrqf^qp-TFi

II Hrdaya-darpana

, as quotedinDhyanyalok

fflocana, Kavyaml

p. 27.

edition,

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

88

ArmaisBORI, LXV ( 1984 )

criticto comparepoetic experienceto thatof the BrahmanwhichtheIndian

traditionregardsas the highestgoal of life. All subsequentwriterson poetics

are indebtedto him forthis brilliantconception. Even Abhinava who has

rejectedhis contentionthat rasa is not a cognitionand that bhavakatvais a

specificprocessin poetic experience,18concedes his descriptionof the poetic

experienceas on a par withthespiritualexperience,and his bhojakatvaprocess

as identical with Ananda's vyarijan. As monistic Saivagama, of which

fromthe monistic

Abhinava is the chief exponent,is basicallynot different

Vednta, indebtednessof the rasa expositionto aivgama needs no special

reference.

whichAbhinavahas

The two salientpointsin Nayaka's interpretation

is

i

and

under

:

not

a

are

rasa

fire

( ii ) bhavakatvais a

)

cognition,

passed

(

. About the

which

sdhranlkararta

about

the

special poetic process

brings

to call rasa a bhogafirst,Abhinava remarksthat it is self-contradictory

pleasure,and at the same timeto denythat it is a pratiti - cognition. What

is pleasure if not a form of awareness or cognition? Abhinava has no

objectionto singleit out fromthecommon formsof cognitionor awareness;

but to call it no cognitionis equivalent to make it unfitforany definition,

- like a ghost!19 As forthe bhavakatva

, Abhinava takes it as anotherselffor

contradiction

has

committed; it militatesagainsthisviewthatrasa

Nyaka

is not produced. Bhavakatvais thesame as bhvan of the Mmmsakas; and

bhvanis conceived as a mental process of a person that causes a thingto

come intobeing. It operatesthroughtwo media: the word and the meaning;

:

and is accordinglynamed &abdi%and rthi, as illustratedby the statements

41 mustdo this.' Mmmsakas

this

ii

me

and

i

to

do

someone

desires

',

( )

( )

is inducedby the Veda

believethatit is throughthisprocessthata performer

to performa ritual,thena will is created in his mind to do it which,eventually,is translatedinto the actual performanceof the ritual. In matters

secular,it is some person in command who playsthe role of the Veda in the

citedexample.20

( Com.), Baaras( 1940), p. 187.

80

^

sfarvmti f

Locana on DhvanyalokawithBalapriya

I*?

, <1^1^WPEH,

188-89.

it

#.

pp.

i

op.

f^TRrra:

in the

conceiveof thebhavakatvaseparately

shouldbe notedthattheMmmsakas

of the bhvan

wordand the sense,whichfactis corroborated

bytheirdivision

intosabdtandrthi.. cf.Kvyapraksaeditedby Arjunwadk^r

aqd Mangrulkar

Poona( 1962), p,0150.

mm wwra:s^qfrm

RWflU^ ^

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Arjunwadkar

: The Rasa Theoryand theDaranas

89

With due respectto Abhinava, T beg to differfromhim in his interpretationof Nyaka on the point of bhvakatva. It is in the contextof

sdhrankarana that Nyaka ushersin thebhvakatva

, which,whenunderstood in the proper spirit,means eliminationof the elementof specificity

from the apparatus of rasa by the spectatoron the strengthof his willpower,- somethingon a par witha ' willingsuspensionof disbelief'. It is a

unique power of the human mind to infuse a lifeless matterwith life, to

associate a thing with or dissociate it fromsomething,to equate something

with agreeable or disagreeablecomplex of qualities. A lifeless pictureor

image, a book, a souvenir, a word, a flower,a smell, a colour, a piece of

furniture,an apparel, - in short, anything,howsoever insignificantfrom

pthers'pointof view,can mean a lot fora personwho infusesit withfeelings

by his will power. It is a symbol for him of somethingwhichexistsin the

worldof his mind. This power of symbolism,whichman discoveredfirstin

the formationof language and extended it subsequentlyto other countless

areas, is perhapsthe one phenomenonthat pervadesthe entire human life.

All arts,plays,games,entertainments,

religious,social or politicalconventions,

are nothingbut manifestations

and

in

notations

all

studies

of

metalanguage

the power of symbolismbacked by individualor social will power. Bereft

of thispower, man would be a poor creaturelike any other. This is man's

bhvan akti, whichI thinkNyaka implieswhenhe speaks of bhvakatva

.

Abhinava's criticismof him on thispointis, therefore,unfairor an outcome

of misunderstanding.Even if Abhinava is supposed to be rightin taking

bhvakatvaas equivalentto bhvan, it deservesto be notedthatwhatNyaka

relatesto it is not rasa but onlysdhrankarana,which,by commonconsent,

can be grantedas produced.

On a close examination of the rasa theoryas understoodby Nyaka

and by Abhinava, one cannot help feelingthatthe latteressentiallyimbibed

the former'sview and developed it to a formone can logicallyarriveat, except on thepoint of bhvakatvaon which Abhinava has misunderstood

from

him, and bhojakatvawhich,for Abhinava, is a cognitionnot different

in terminology.

vyanjan, - i.e. a matterof difference

As detailed by Abhinava, rasa is different

from sthyininasmuchas

the formercan abide onlytemporarily

and only in a connoisseur( sahrdaya),

whilethe latter exists dormantlyand permanentlyin everybeingfromthe

moment he is born. In other words, rasa exists only in drama ( or other

arts), sthyinsexistonlyin actual life. Rasa exists only as long as theact

of carvan- relishing- continues: and carvancontinuesonlyas long as the

rasa apparatus- vibhva etc. - is in view.21 That is the reason why the

21

^

flfr:

V&T 3

'2 [AnnalsBORI]

| Kang.154.

^1

I Kang.167.

TTf

snfsSTT

1 Kang.174.

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

tTf

f|

90

Annals BORI , LXV ( 1984)

correlativesof rasa cannot be regardedas havinga causal relation withthe

latter; because an effectlike a pot exists independentlyof the potterwho

makesit, once it has come into being. This leads us to the inevitableconclusionthatthe experienceof rasa has no parallel in actual life and hence

must be regardedas alaukika, uncommon.22The relationbetweenrasa and

its correlativesis explainedon the analogyof the pot and the lamp, - ghata,23and is called vyanjan. The pot is revealed,not produced,

pradpa-nyya

the

by

nearby lamp only as long as the lamp emitslight. Rasa too, which

alreadyexists in the forma sthyinin the mind of the spectator,is likewise

revealedto himby its correlativeswhenit assumestheformof a rasa. Before

: shornof its

this stage is reached,the sthyinundergoes a metamorphosis

this

is

sdhrankarana

. As a

is

it

generalised,

space-time-personcontext,

as

nor

his opponent's,

result,it is experiencedby the spectatornot as his own,

nor of a third party person, leaving thus no scope for such relations as

This experiencedoes not partakeof

embarrassment,

angeror indifference.24

not

it

is

the characterof memory(for

producedthroughthemediumof sense

organs), or inference( forit is relished),25- though,of course, the faculty

of inferencein the spectatoras he utilizesit in worldlyaffairslays thefoundation for the experienceof rasa. Hence it is a unique, pure experience#

by any othercognitionand unpollutedby any worldly motive'

uninterruped

verymuch like the experienceof the supremeBrahmanand, likewise, constitutedof purehappiness. The mostlogical concluion of this view is that,

theoretically,rasa is only one ( Brahmsvdadoes not have varieties), a

thread,not taken noticeof by othersbut taken up lateron by Bhoja and

elaboratedto its fullestextent.

22 m ^

R

rgt^mirsfq

?

Teff:,

174.

Kang.

I

q^rrq

23 T|

^

tosrti; i

sGfcraft

Pfa

^

qpj*

srtasraRl

I m? ft

I Dhvanynloka

,

^35

TOWRRfr

1 ...

Trfc

pp.421,431.

proseunder3.33,Blapriyedition

'

24 ...

m9

smsit

<TT

qt

qsf

... f?.sjr<

^ i Kang-154.^n^i^ar . . .

MsrsrfrlctTif

11 ^

i 3T

i ^ wcfiif

^ ^ astrai

I ^

*

%

I =*faCTTO&FKRRT

H^-WTRf,

I Kang. 179.

SJfR:

^

TTWJf^T

25 ?i ^ rr

^

i ^

S7lHi-au'

,T

_

N

174

Kang.

^"TI

I

^

1%

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

rJUNWADKAR: The Rasa Theoryand theDar anas

For theconceptof vyajana, also called dhvani, foundin an elaborate

formforthe firsttimein the workDhvanyloka

, nanda has acknowledged

his debt to grammarianswho firstenunciatedthis principlein the contextof

sphota, a typicalsemantic concept of thePninian school. For Pninians

the audible wordconsistingof sounds comingone afterthe other, the earlier

one disappearingbeforetheadventof the nextone, and, hence, incapableof

forminga unitedwhole,cannot conveythe meaning. They have surmounted

this difficulty

by conceiving an eternal form of the word, the sphota,

which being partless, encountersno problem in conveyingthe meaning

whichthe audible, perishableworddoes. But how come we get at theeternal

wordfromtheaudible,perishableone ? Througha processcalled vyajana'

say the grammarians. The transitorysounds leave their impressions

on the mindof the listenerbeforetheydisappear; and the last sound of the

word togetherwith the impressionsof the earlier ones reveals through

vyajanathe eternalword, sphota, whichin its turnconveysthe meaning.26

This processof vyajanaas conceivedby the grammarianshas not a very

role to play in the corpus of the formal grammar. Thanks to the

significant

acumen of nanda who realizedthatthis conceptcan contributesubstantially to the criticismof poetryand elaboratedit in a systematicmanner; and

it changedthe whole outlook of Sanskritcriticismin the yearsthatfollowed.

What Nyaka calls bhojakatva (only in the context of rasa) and

Ananda-Abhinava school vyajana( in a wider context even outside the

span of rasa ) is controverted

by JayantaBhatta summarily,and Mahima

Bhatta in detail, who have upheld the claim of inferenceas the rightful

operant in areas where vyajana is supposed to operate.27 Mahima has

done this more systematicallyand in sufficientdetails than Jayanta. For

them the apparatus of rasa ( vibhva etc. ) is as much a cognitivetool

(japaka-hetu) of the sthyinjrasaas is smoke, of fire. They see no reason

between the two and whythe former

why thereshould be a discrimination

26

^fir^Fq: 3^3^:

Pnini-darsana.

'

Sarva-darsana-saihgrahat

Vakyapadiya

, 1.85.

2T Cf. Vyakti-viveka

1909), 1.26,52, 53. Mahimacalls thisprocess

( Trivandrum

it fromthe non-poetic

( 1.25) to distinguish

Kvynumiti

inference.

For him,as

itis theinference

thatoperateseven in the area of the

expected,

maybe logically

See also ATyayci-munjcivi

sphota of the grammarians.

( KsishTSarskrta

Series,

1936), p. 45,whereJayanta

nandaas panditammanya

disparages

. Theviewthat

inferencecan dispensewithvyanjan existedeven at the time of nanda

and refuted

whohas presented

it in hisownway. See Dhvanylokaunder3. 33.

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Annals BORI , LJSTF( 1984 )

92

be givena VIP treatment.Of course,of thetwo criticsof vyajana, Jayanta

is candid enough to concede that, afterall is said and done, this is the field

of the criticsof poetryand too profoundforthe logiciansto pass a judgment

on.28 Mahima is not that liberal. He not only argues out the case of

inferenceagainst vyajana but also slashes Ananda forlack of carefulness

in the wording of his statements. In a small verse by nanda in the

earlypartof his workwhichdefinesdhavni,Mahima has picked up as many

as ten errorsand, in a sneering-cum-ridiculing

manner, presentedit in a

29

the

!

form

errors

by correcting

recomposed

Mammata, in his Kavyaprakaa,has squarelydealt withthearguments

of Mahima. Inferenceas a means of right knowledge has as its basis an

invariableconcomitance( vypti) of thehetuwiththesdhya. In theabsence

of such a vypti, any inferencedrawn is open to prove fallacious. No

such vyptican be established betweenthe vyajaka and the vyagya

; and

hencethe verbaloperation like vyajana is inevitable to account for the

poetic experience.30Mammata has also recordedviewsof otherrivalschools

opposingvyajana( suh as inclusionthereofin laksan, the drgha-abhidh

view etc.); but as the topic underdiscussionis primarilythe rasa theory in

its relationto thephilosophicalsystems,going into the detailsof Mammafa's

would be out of

argumentsin favourof vyajana,howsoeverinteresting,

place.

As statedearlier,thethreadin Abhinava's expositionof rasa thattheoreticallyit is one was latertaken up and elaborated by Bhoja. Bhoja does

not subscribeto the traditionalview that there are eightor nine rasas in

dramaor poetry. It is a myth,handed down fromgenerationto generation

and followedblindlylikea beliefthata certaintreeis inhabitedby a ghost!S1

Whatare popularlycalled rasas are no more than bhvas generatedfrom

therasa, and theyneed not be limited to the sacred number eight or nine;

! Whyshould onlya fewof thembe promoted

theyare as manyas fortynine

to the status of rasa ? We findone logical end in Rudrata's answerto this

82

question: thattherecan be as many rasas as there are bhvas,i. e. 49.

28

29

80

i

82

13: I loc. cit. This

f%

JTtgqi

of Jayanta

is generally

overlooked.

statement

1.23,25.

Vyakti-viveka,

Kavyaprakaa,Ullsa5.

itfO

i drhgara-praka,

^ mraf: rasi fsflsfq

4Bhjas rngaraPraksa' Bombay1940.

See Rghavan's

I

, 12.3,4.

Kavylankara

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ArJUNWADKAR: The asa Theoryand thearatias

$3

The otherend is foundin Bhoja's position that none of the 49 candidates,

who play alternatelythe principaland the subordinaterole*in relation to

one another,deservesto be electedas rasa, whichis above themall.33 Bhoja

names thisone rasa variouslyas abhimna, ahamkra and rgara ( which

mustnot be confusedwithits namesakein Bharata's exposition). Rasa is

what is relished,is the subject of svda. And what is it that we really

relish? Our own ego says he; and explainsit as self-love.34 Whateveris

liked, disliked, loved, hated, welcomed, avoided, is the subject of anger,

sorrowor surprise,- all thathas an invariable referenceto one's own self.

This principleof ego is so overwhelmingthatit can converteven pain into

pleasureand vice versa. A younggirlfeelspleasureat the scratchesmade by

her lover's nails on her bosom; why? Her ego is theanswer.35 It is plain

thateveryman is happyor sorryfortheprofithe makesor theloss he incurs.

Even whenhe is happyor sorryforanotherman's profitor loss, it is for himselfin an indirectway. That a man makes a sacrificeforanother is also for

himself- forthe satisfactionhe obtains therefrom.That he weepsfor anotheris also forhimself. It is the self-lovethat is the source of all a man

does or does not. Even Yajavalkya and Manu do not thinkotherwise;86

and, above all, no one can denyone's own experience.

This ego is a qualityof the soul; and, hence, whosoeverhas a soul has

also an ego. Its refinement

whichmakes the rasika is the achievementof its

cultivationduring a seriesof past lives.37 The ego, accordingto the Samkhya theory,is constitutedof sattva, rajas and tamas. It develops into

rasa whentheelementof sattva reigns. Bhoja conceivesit in three stages:

the first,pureego; the second, wherethe 49 bhvas get a scope to be enriched

33

3T?qcrq

qlfa q^qt

|

3 sqfRTfl

ifft

stsf artftsq^rf^T:,

^ qifp: | Bhoja's rhgra

Prakasa p. 517.

84 W 9

intro.

I Qrhgaraprakasa,

5.1

Sarasvati-kanthbharana

85

I

# frg spir^ ^

SFJIWT

II Bhoja'sr'ngaraPraksa p. 516;See also

527.

484,

465-66,

pp.

Brhadranyaka%

4.5.6.

Sfjfi

R3^ 3fl?R:

2. 4.

II Manusmrti,

I

^cRJcT

3fl*n

I ... iffld

ft

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

94

Annals BORU LXV ( 1984 )

by their respectivevibhva etc. when they are called rasa in a secondary

sense; the third, the fullydeveloped stage where the bhvas enrichedin

the second stage merge into one single awareness- self-love. Bhoja has

openly acknowledgedhis debt to the Smkhya system.38 But there are in

his exposition of rasa as he understandsit conceptslike karman, vsan,

punarjanmawhich are commonlyshared by almost all Indian philosophical systemsand are drawnupon tacitlyor with acknowledgementas much

by Bhoja as by otherexpoundersof rasa like Abhinava.

Jagannthais the last doyenof theSanskrittraditionof criticism. He

has enlisted as many as eleven views on rasa includingthose discussed

by Abhinava. Only the firstfourof these views are givenby him in detail,

whilethe restare coveredin a fewlines,the last five receivinghardly a line

in Jagannatha'streatmentof rasa is that he

each.39 The obvious difference

a

in

material

his

stylecultivatedby the Navya Nyaya and

mostly

presents

adopted by the post-Gagea works on Vednta. Following the ancients,

he firstpronouncesthe character of rasa as the sthyinqualified by unthe statementby saying that 4in

coveredconsciousness; and later rectifies

.'40 The diffefact,rasa is uncoveredconsciousnessengulfedby the sthyin

rence between these statementsis like that between the coloured glass

illuminatedby thesunlight and * thesunlightfilteredthroughthe coloured

*

glass. As a truescientist,he makes it categoricallyclearthattheexperience

of rasa, engulfedby objects such as vibhva, is quite distinct from the

, he has traced

experienceof the Brahmanin meditation.41As a truevedntin

the

oldest

a

ruti

to

rasa

possibleauthorityrespectedby all devout

passage,

third

the

he has ascribed to 'moderns', he

In

traditionists.

interpretation

with

the

on

a

rasa

appearance of silver on a shell shining

par

presents

caused

both

in the Sun,

by imperfectionsin cognitive conditions, and

indeterminate.42

Otherswould like to call themboth

,

equally anirvacanya

ftW*

^cfI Bhoja s rhgaraPrakasa, pp. 464,465.

88 s

3

^ 5JK:Rf.

...

^ aflffof,

p. 465,491.Cp.

I Op. cit.

9.

Il Smkhyakrik

WMHH ^

89 Rasa-gahgdhara

54-74

B.

Athavale's

edition

in

R.

I, pages

( Poona 1953). Vol.I.

feraci

'

^ h:, l

41

42 qsqrcg ...

w i ...

...

Cit.

I op.

p. 55.

icfgf:

I loc.cit.

...

| Op.cit,pp.56-57.

SgKWWS&Fte...

'

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ArJUNWADKAR: The Rasa Theoryand theDarianas

95

illusions.43 These are practicallyextentionsto rasa of various khytisin

philosophicalsystemswhich attemptto explain what happens whenX is

cognizedas Y.

From the surveyof the views on the rasa theoryfromLollata to

Jagannthamade so far,it will be clear that, althoughit is marked by some

viewsthatmay be termedpoles apart and some as of no consequence, the

main stream of thought startingwith Bhatta Nyaka and ending with

Jagannthaflowsalong a locus representedby the thoughtcomplex of what

may be called the Smkhya-Vedntagrid, I am using the term 'grid*

because, excepton a veryfewbasic concepts,the two systemshave identical

viewson a numberof philosophicalpoints. The very idea thatrasa is not

, has a

producedbut alreadyexists,it is only revealed,is one withthe sthyin

close resemblancewith the doctrineof satkryavda

which

is

shared

,

by

both the systemsand whichcontendsthatthe effectis not produced out of

nothingbut existsin its materialcause even before its productionand is alwaysone withitand thatit is nothingbut the materialcause in a new form

brought about by the efficient

cause/s. The idea of sdharanikarana first

propoundedby Nyaka has its roots partlyin the Smkhyaconceptthatthe

purusa, reallynot rela'ed to thegunas whichcause bhoga, is subjectedto the

in error,with the prakrti

worldlyexperiencesbecause of his identification,

which is reallyconstitutedof thethreegunas; and partlyin the Vedntaidea

that all is Brahman. Yet another probable source for sdhrunkaranais

thesmnyaconceptof the Nyaya-Vaiesikasystems44whichis thecommon

heritageof most of the philosophicalsystems. It is particularly

in

significant

thiscontextthatthe Smkhyas are fondof comparing the role of theprakrti

withthatof an actress who presentsthe drama of pleasureand pain on the

stageof the world, that is, the samsra, in whichthepurusagetsinvolvedso

long as he does not realize that he is in no way a partof it. As soon as he

5 We have seen

realizes it, the drama ends forhimand he attainskaivalya.*

Op,cit.p. 73.

CP-^

fit

m

2. 2. 68

| Vtsyyana's

BhsyaontheNyya-dariana

45 ^

fNiftfirtm

I

CTfJH

Tff:Il

ita

I

TT^fflfrtq;

Samkhya-krika

59, 65. The pointtobe

notedhereis thatthespectator

is viewedhereas notinvolved

inthe dramagoingon

before

him,whilethetheoryof rassvda presumes

involvement

of the specta-<

torinthedramatoa certain

extent.

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

96

Annals BORI , LXV (1984 )

how Bhatta Nyaka has contendedthat it is not possible foran ordinary

charactersas Rma,

spectatorto identifyhimselfwith such extraordinary

To this, Abhinava's reply is that this is not impossiblewhenwe consider

the wide rangeof highand low formsof lifethroughwhicha soul passes and

Carriesimpressionsthereofin the seriesof lives,markedby birthsand deaths,

to whichhe is subjected in this anadi samsara. Again, the idea of happiness as the outcomeof all rasas has its rootsin the Upanisadic conceptof the

Brahman as constitutedof sat, cit and nanda. The novel rasa theoryexpounded by Bhoja is unquestionablyfoundedon the Smkhya-Vedntagrid;

witha marked Smkhya bias, both in conceptionand terminology. It will

thusbe clear thatthe theoryof rasa as developed, apparentlyon the basis of

Bharata's Rasastra, mainlyby the Smkhya-Vedntagridwill be deprivedof

its characteristicfeaturesif shorn of its moorings in Indian philosophical

systems.

fromthe view of thetradiThis conclusion,however,is quite different

thereofare represenof the Rasa-stra that interpreters

tional commentators

tativesof various philosophicalsystems( as we have noted above in thecase

pf akuka etc. ). An attempthas recentlybeen made to revivethisview by

Dr. Sunil Subhedar of theNagpur Universitywho delivereda seriesof three

}ecturesin Bombay on the 17th-19thDecember, 1976, underthe auspices of

theMumbai Marathi Sahitya Sangh. These lectures werelatelypublished

(1981 ) under the title Njyadar&ana. Dr. Subhedarhas, in theselectures,

treatedof threeaspectsof Indian drama,viz. ( 1 ) The Indian Drama : Tradition and Philosophy; ( 2 ) The Rasa-stra ofBharata; and ( 3 ) Philosophy

$nd theWesternDrama. The scope of the present discussionis limitedto

the main argumentin the second lecture.

to defend traditionalwisdom, Dr. Sunil Subhedar

In a valiant effort

of theRasa-strais possiblebydiscardarguesthatno correctcomprehension

FollowingprimarilyJhalkikar,the learned

ing thetraditionalinterpretations.

Sanskritcommentatorof the KvyaprakSa> he introducesthe five interpretationsby Lollata, akuka, Bhatta Nyaka, Abhinava and Jaganntha

as representingthe views of Mmms, Nyya, Snkhya, Vykarana and

Vdnta on the Rasa-stras9and maintainsthat, fora properunderstanding

of theviews, a close knowledgeof the basic principlesof these systemsis

essential. He furthermaintainsthat, once this stand is taken, what is left

forus is to acquaint ourselveswiththe hypothesesof these systems,draw

PhWKiJ ...

' Locana on

Dhvanyloka2.4.

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ArJUNWADKAR: The Rasa Theoryand theDaranas

97

conclusionsa priorifromthem and not question them a posteriorion the

strengthof our personal experiencesin total ignornace of the scientific

method47

It is perfectly

legitimateto say thatone should make an earnesteffort

to understandthe view of an interpreter

and acquaintoneselfwiththesystem,

if necessary,from which he draws his material. But to denythe rightof

vis--visone's own experienceis not onlydoing

questioningthe interpretation

to

the

but

also to the spiritof the tradition. The surest

injustice

questioner

confirmation

of a hypothesisis considered to be the agreementof its results

withactual experience.eWhat AlmightyExperiencedictatesus, we will obey,*

proclaims JayantaBhatta,48the learnedauthorof the Nyya Manjar/, and

whatis it, ifnot experience,whichis held as the touchstoneby the traditional

critics of the interpretations

in refutingviews they do not subscribe to?

Could therebe a strongerdefenceof experiencethan that by amkarcrya,

the doyenof Indian philosophers,whenhe remarks: 4Even a hundred ruti

passages cannotbe accepted iftheytell us thatthe fireis cool and devoid of

light'?49 The most astoundingfactis thatthe Mmmsakas seek sanction

fortheirtenetsfromcommonworldlyexperience,50

and Subhedarshutsdoors

to the latterin favourof theformer! Subhedar's argumentsare based on the

thatthereis an uninterrupted,

uniformtraditionof the interpretapresumption

tionsof the Rasa-strareachingas faras Jhalkikar,i. e., almost to our own

times.Againstthisbackground,it is amusingto findSubhedarsurprisedat the

factthat, in a long periodof one and a half millenniasince Bharata, Jaganntha was thefirstto cite passage from the TaittiriyaUpanisadin support

of the so-calledVednticview of Rasa-stra.51 This is equivalentto saying

thattherewas no Vednta traditionas such of the interpretation

of the Rasa sutra, and thatit was Jagannthafirstto thinkof utilisingVednticconcepts

and terminologyfor the interpretation

of the stra. And what whenthere

the

two

in

tradition

itself

in

to one or the

are

opinions

relatingan interpreter

othersystem,52

or whenan interpreter

borrowsfrommorethanone systems?58

47 See Natya-darsana(Bombay1981), pp.36-54.See also Rasa-vicara ani Pracina

DarsanakrabyMM. YajesvaraSstrIKasture,

1957.

Hyderabad

4:8 p

: I Nyaya Manjar (Benares1936),

Pramna.

p. 285.

49 * |

18.66.

l Glt-bh.ya

Sprat

co Cf.Mmamsa-Nyaya-Prakasa

, Introduction

:

byMM. VasudevaShastriAbhyankar

p. 2i.

Natya-darsanap. 53.

52 BhattaNyakaregarded

as a Simkhyais blamedby Abhinavaforhavingfounded

histheory

ontheMlmmsconcept

ofbhvan. See Note20 above.

63 Bhatta Nyaka,again. Regardedas a Smkhya,

he was the firstto compare

rasasvdato Brahmasvda of theVedntins.Whatis hisidentity

? A Samkhya,

a Vedntinora Mimam

saka (cf.Note52) ?

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

98

Annals BORI , LXV ( 1984 )

This bringsus to the nextimportantpoint. The so-called Mmarsaka

etc. viewsof the Rasa-straare no more thana utilizationof some Mmms

etc. principlesforan issue outside thejurisdictionof the systemconcernedif

of the issue. What

theyare thoughtto be conduciveto a betterunderstanding

a solution to a

interestis a philosophical systemlikelyto have in offering

in

unsurmountable

?

land

an

We

may

problemit does not considerits own

ifwe wereto thinkthata systemhas a viewabout everyingunderthe

difficulty

sun. If a Mmmsaka carrieshis own theorieswhenhe turnsto Rasa-stra,

whatwould he do when he turnsto Vedntaor Vaiesika? Could therebe

anythinglike a Mmmsaka view of the Vedntaor the Vaiesika? What we

actuallyfindis thatan author havingcommandover severalsystemsor disciplines( like Vcaspati Mira ) is a Smkhya whenhe expoundsSmkhya, a

Vedntin when he expounds Vednta and so on. If Smkhyatenetsfigure;

as a criticof the

in theinterpretation

of theRasa-stra, it meansthe interpreter

rasa theoryhas borrowedsome Smkhya tenetsforhis convenience. The

advantagehe derivesby doing so is thatit is the Smkhya, and not he, who

is answerableforthetenetsreliedupon.

More discrepanciesare disclosed when we go into the details of

Subhedar'stheory. Lollata is a Mmmsaka, he maintains. Why? Because

the role the actor plays in a drama is comparableto thatof the sacrificer

in the Vedic ritual,suggestsSubhedar. There is nothingin the interpretation

of Lollata to provethathe had this in his mind when he propoundedhis

theory. Even if we ignorethis, the basic question is how can comparison

fromthe Vedic ritualbe regardeda part of the Mmms system which is

essentiallythe scienceof interpretation.That this science expoundsits tenets

withthe Vedic ritual in view is no reason whythe two should be treatedas

one, and Lollata as a Mmmsaka. If Subhedar is supposed to bs rightin

readingthe mindof Lollata, Lollata can at thebest be regardedas a ritualist,

not a Mmmsaka.

'

Equally untenable is the view that akuka is a Naiyyika on the

groundthathe regardsrasa as inferable.Nyya is a systemthatexpoundsin

detail all the four means of knowledge of whichinferenceis one. When

akuka maintiainsthat rasa is inferred,what typicallyNyya idea is involved in it which makes him a Naiyyika? Do I need to be a Naiyyika

when I inferor say that my missingshoes kept outside the house have

been stolenby someonewhileI was engagedinside? If akuka's theoryof

inferenceis adequate to deem him a Naiyyika, his referenceto Dharmaklrti

can be regardeda sufficient

groundfordeeminghim a Buddhist! In support

of his contentionthat Bhatta Nyaka was a Srkhya, Subhedar quotes

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

rjunwadkAR : he Rasa Theoryand theDaranas

99

the Smkhyaterminology

he employs,conveniently

ignoringthe comparison

of the rasa experiencehe makes with the experienceof the Brahman. I

do not know of a Smkhya systemwhich shares the Vedntic concept of

Brahman and its experience. If Bhatta Nyaka is a Smkhya because he

employssome Smkhyaconceptsin expoundingthe Rasa-siitra, whyis he not

a Vedntistbecause he employssome Vednticconcepts? And Mmamsaka,

too, because, as interpreted

by Abhinava, he impliesthe bhvanconcept

of the Mimmsakas whenhe talksof the bhvakatvaprocess?

Subhedar's stand becomes all the more unconvincingwhen he introducesalamkraview of the Rasa-sutraas the view of the grammarianson

the strengthof theclich thatpoeticsis the tail ' of thegrammar,'

' Puccham' here means, forhim, a

respectableor dignifiedsequel as

'

But unlike Marathi,

illustratedin the Vedic passage,

'

srffT

' in thissense. Pratisthin Sanskrit

Sanskrit does not use the word ' srfgT

means *position,support,basis Nowherein his exposition,Subhedarseems

to be aware of this. This is funbased on a confusion.

as one representing

Subhedarhas introducedAbhinava'sinterpretation

the view of the grammar- he means the Pninian school, and Jagannatha's

as one of the Vedntins. Elsewhere in his exposition of thistopic, he has

attemptedto show how the two schools are veryclose in theirview of the

creationof the world. What is Brahmanto the the Vedntins,the ultimate

cause and reality,is the abda-Brahmanto Grammarians,says he, and takes

the conceptas farback as Panini and Patajali. Now, thereis no evidenceto

provethatPaniniand Patajali had thisconceptin theirmind. The firstwork

that expounds this concept is the Vkyapadya of Bhartrhari( 6thc.A.D. );

and thereare reasonsto believethathe, too, meantit in a metaphorical,rather

thana metaphysical,sense. Ngoji Bhatta ( 18thcent. A.D. ), therenowned

exponentof the Pninian school, understandsthe abda-Brahmanas produc

'

ed, and hence the apara % and not the para ' Brahman.54 If, however,

Subhedar believes that the two systemsare almost identicalin theirmetaphysicalview,it is not easy to understandwhyhe treatsthemseparatelyin

theirviewsof the Rasa-stra, whichare weddedto theirmetaphysicalviews,

as Subhedarmaintains. Subhedar believes that it is the influenceof the

monisticidea of the Brahmanthat led Jagannthadefinepoetryas abda *

in preferenceto the conventional ' abdrthau' which involves dualism.

See Vaiyakarana-Siddhanta-Laghu-Manjusat

...

(Chowkharaba

edition,

p. 172)

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ioo

Annals BORI, LXV ( 19S4 )

Jagannthadoes not seemto be aware of this; forhe justifieshis definition

by

to such commomexpressionsas thepoetryis recitedaloud 'M

a reference

We have no means to guess what Subhedar thinksof Bhoja's interpretationof rasa. Is Bhoja a Smkhyaor a Vedntin? Tneitheralternative,

how is Subhedargoingto account formore thanone interpretations

fromthe

same school and reconcilethis situationwithhis beliefthatthe various interpretationsof therasa theoryhave come downto us througha uniform,unbroken tradition? We are, therefore,forcedto conclude thatthereis no such

of theRasa-sUtraby philosophicalsystemslike

thingas oficial interpretations

Mimms; thatall those who offeredto interpretthe Rasa-sra did so as

criticsof drama and/orpoery; thattheysought aid from the philosophical

systemsin varyingdegreesin the hope of solvingproblemsrelatedto the issue

at hand; and, last but not the least, theydid so with an eye on the actual

experienceof theconnoisseuras a touchstoneforthecorrectnessor otherwise

of thetheory. Abhinava has succeeded in drawingthe best fromhis predewhich is least susceptibleto inconsiscessorsto formulatean interpretation

own

limitations.

has

its

but

tency

i ' 3^5^:

ifRr+rrcft.

^(^JSR^^itRd:

Sjfl

jisqi ^ fTRT:,'

ofthekvya.

, definition

Rasa-gahgdhara

qatf,

This content downloaded from 194.95.59.195 on Sat, 14 Feb 2015 16:23:36 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Tattvabodha (Volume VII): Essays from the Lecture Series of the National Mission for ManuscriptsFrom EverandTattvabodha (Volume VII): Essays from the Lecture Series of the National Mission for ManuscriptsNo ratings yet

- Buddhacarita of Asvaghosa A Critical Study PDFDocument12 pagesBuddhacarita of Asvaghosa A Critical Study PDFManjeet Parashar0% (1)

- Ollett2016 Article RitualTextsAndLiteraryTextsInADocument15 pagesOllett2016 Article RitualTextsAndLiteraryTextsInASasha Gordeeva Restifo100% (1)

- Natya Shastra in SanskritDocument5 pagesNatya Shastra in Sanskritsathya90No ratings yet

- Religions 08 00181Document11 pagesReligions 08 00181Nenad PetrövicNo ratings yet

- Hanneder ToEditDocument239 pagesHanneder ToEditIsaac HoffmannNo ratings yet

- Shaivism and Brahmanism. Handouts 2012-LibreDocument125 pagesShaivism and Brahmanism. Handouts 2012-Libre23bhagaNo ratings yet

- उपमाDocument32 pagesउपमाmukesh8981No ratings yet

- Anagatavamsa DesanaDocument5 pagesAnagatavamsa DesanaCarlos A. Cubillos VelásquezNo ratings yet

- Abhinava Aesthetics LarsonDocument18 pagesAbhinava Aesthetics Larsondsd8g100% (2)

- 17 - chapter 8 (含部分八大瑜珈女神的Dhyana Mantra) PDFDocument33 pages17 - chapter 8 (含部分八大瑜珈女神的Dhyana Mantra) PDFNaNa BaiNo ratings yet

- Annals of The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Society Vol. 24, 1943, Parts 1-2Document391 pagesAnnals of The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Society Vol. 24, 1943, Parts 1-2mastornaNo ratings yet

- Shiva: The SupremeDocument15 pagesShiva: The SupremenotknotNo ratings yet

- The Vedas in Indian Culture and History-6 PDFDocument24 pagesThe Vedas in Indian Culture and History-6 PDFViroopaksha V JaddipalNo ratings yet

- The Carvaka Theory of PramanasDocument5 pagesThe Carvaka Theory of PramanasLucas BarbosaNo ratings yet

- Ashtami MahotSavaDocument8 pagesAshtami MahotSavadrgnarayananNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Implications of Dhvani: Experience of Symbolic Language in Indian Aesthetic by Anand Amaladass. Review By: Bimal Krishna MatilalDocument2 pagesPhilosophical Implications of Dhvani: Experience of Symbolic Language in Indian Aesthetic by Anand Amaladass. Review By: Bimal Krishna MatilalBen WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Folk Tradition of Sanskrit Theatre A Study of Kutiyattam in Medieval Kerala PDFDocument11 pagesFolk Tradition of Sanskrit Theatre A Study of Kutiyattam in Medieval Kerala PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- 30.8 Upaya Skillful Means. Piya PDFDocument53 pages30.8 Upaya Skillful Means. Piya PDFpushinluck100% (1)

- Annambha A Tarka-Sa Graha Athalye Edition2Document67 pagesAnnambha A Tarka-Sa Graha Athalye Edition2matthewdasti100% (2)

- The Agganna SuttaDocument10 pagesThe Agganna SuttaMauricio Follonier100% (1)

- Madhva’s Unknown Sources: A Review of Claims and EvidenceDocument18 pagesMadhva’s Unknown Sources: A Review of Claims and EvidenceHari-Radhacharan DasNo ratings yet

- Mimamsa Ekavaakyataa PDFDocument66 pagesMimamsa Ekavaakyataa PDFdronregmiNo ratings yet

- Brahma Sutra Part OneDocument11 pagesBrahma Sutra Part OneJovana RisticNo ratings yet

- Avikalpapraveśadhāra Ī: (626) 571-8811 Ext.321 Sanskrit@uwest - EduDocument6 pagesAvikalpapraveśadhāra Ī: (626) 571-8811 Ext.321 Sanskrit@uwest - Educ_mc2No ratings yet

- Ha Savilāsa Propounds A Metaphysical Non-Dualism That Views Correlated Male and Female Identities AsDocument19 pagesHa Savilāsa Propounds A Metaphysical Non-Dualism That Views Correlated Male and Female Identities AsDavid FarkasNo ratings yet

- The Megha DutaDocument138 pagesThe Megha DutaSivason100% (1)

- Prauda Manorama Laghu Shabda Ratan Prabha Vibha Jyotsana Kuch Mardini - Sadhashiva Shastri 1934 - Part1Document315 pagesPrauda Manorama Laghu Shabda Ratan Prabha Vibha Jyotsana Kuch Mardini - Sadhashiva Shastri 1934 - Part1vintageindicbooks100% (10)

- Veda Recitation in VarangasiDocument6 pagesVeda Recitation in VarangasiAnonymous Fby2uhj3sKNo ratings yet

- Bhasmajabala UpanishatDocument8 pagesBhasmajabala UpanishatDavid FarkasNo ratings yet

- Iṣṭis to the Lunar Mansions in Taittirīya-BrāhmaṇaDocument21 pagesIṣṭis to the Lunar Mansions in Taittirīya-BrāhmaṇaCyberterton100% (1)

- Jabal UpanishadDocument2 pagesJabal UpanishadDavid FarkasNo ratings yet

- Bisschop, Peter and Yuko Yokochi. 2021. The Skandapurana Volume - VDocument314 pagesBisschop, Peter and Yuko Yokochi. 2021. The Skandapurana Volume - VShim JaekwanNo ratings yet

- Olivelle - Life of The Buddha - IntroductionDocument23 pagesOlivelle - Life of The Buddha - Introductiondanrva0% (1)

- The Sārārthacandrikā Commentary On The Trikā Aśe A by Śīlaskandhayativara PDFDocument7 pagesThe Sārārthacandrikā Commentary On The Trikā Aśe A by Śīlaskandhayativara PDFLata DeokarNo ratings yet

- Alikakaravada RatnakarasantiDocument20 pagesAlikakaravada RatnakarasantiChungwhan SungNo ratings yet

- The Denotation of Generic Terms in Ancient Indian Philosophy Grammar, Nyāya, andDocument334 pagesThe Denotation of Generic Terms in Ancient Indian Philosophy Grammar, Nyāya, andLangravio Faustomaria Panattoni100% (1)

- Hari Vamsa On Birth of KrsnaDocument13 pagesHari Vamsa On Birth of KrsnaAnonymous 36x9DZ3KNL100% (1)

- Ahajavajras - Integration - of Tantra Into Mainstream BuddhismDocument33 pagesAhajavajras - Integration - of Tantra Into Mainstream BuddhismjdelbaereNo ratings yet

- Sanderson - Hinduism of Kashmir ArticleDocument42 pagesSanderson - Hinduism of Kashmir Articlevkas100% (1)

- (Palsule 1955) A Concordance of Sanskrit Dhātupā HasDocument211 pages(Palsule 1955) A Concordance of Sanskrit Dhātupā HaslingenberriesNo ratings yet

- Sree Yoga Vasishtha (Venkateswarulu) Vol 6 (5 of 5)Document88 pagesSree Yoga Vasishtha (Venkateswarulu) Vol 6 (5 of 5)Turquoise TortoiseNo ratings yet

- Panchapadika - Of.padmapada. English PDFDocument460 pagesPanchapadika - Of.padmapada. English PDFhoraciomon100% (1)

- Tantrayuktis-Technical Tools of Indian Research MethodologyDocument7 pagesTantrayuktis-Technical Tools of Indian Research MethodologySurendra KomatineniNo ratings yet

- Yanmandalam Gayatri Stavan Hindi Sanskrit Lyrics PDFDocument4 pagesYanmandalam Gayatri Stavan Hindi Sanskrit Lyrics PDFAbhishek JoshiNo ratings yet

- Avatāra - Brill ReferenceDocument8 pagesAvatāra - Brill ReferenceSofiaNo ratings yet

- On The Sharada Alphabet (Journal of The Royal Asiatic Society 17, 1916) - Sir George Grierson KCIE MRASDocument33 pagesOn The Sharada Alphabet (Journal of The Royal Asiatic Society 17, 1916) - Sir George Grierson KCIE MRASmalayangraviton100% (3)

- PTS - Jinacarita - Rouse W PDFDocument76 pagesPTS - Jinacarita - Rouse W PDFyolotteNo ratings yet

- Sanskrit Riddles 1: When Hanuman Killed Rama, Sita Felt Happy. The Demons Wept Crying "Alas, Rama Is Dead"Document1 pageSanskrit Riddles 1: When Hanuman Killed Rama, Sita Felt Happy. The Demons Wept Crying "Alas, Rama Is Dead"sri_indiaNo ratings yet

- Patanjali S Vyakarana Mahabhashya Samartha Ahnika P 2 1 1 Ed TR S D Joshi Poona 1968 600dpi LossyDocument282 pagesPatanjali S Vyakarana Mahabhashya Samartha Ahnika P 2 1 1 Ed TR S D Joshi Poona 1968 600dpi LossyvartanmamikonianNo ratings yet

- Indian Poetics MassonDocument14 pagesIndian Poetics MassonSri Nath100% (1)

- DhwaniDocument10 pagesDhwaniSachin KetkarNo ratings yet

- Bailey Pravrti-NivrtiDocument20 pagesBailey Pravrti-NivrtialastierNo ratings yet

- Bhagavad Gita Sankarabhashya Sridhari Anandagiri Tika Jibananda Vidyasagara 1879Document880 pagesBhagavad Gita Sankarabhashya Sridhari Anandagiri Tika Jibananda Vidyasagara 1879Harshad Ashodiya Interior Designer100% (1)

- Cuneo 2008-2009, Emotions Without Desire (PHD), Vol. IDocument462 pagesCuneo 2008-2009, Emotions Without Desire (PHD), Vol. IVedant Viplav100% (1)

- 07 - Chapter 1 PDFDocument188 pages07 - Chapter 1 PDFakshat08No ratings yet

- Damage Book on Shabara Bhashya Volume 1Document752 pagesDamage Book on Shabara Bhashya Volume 1ahnes11No ratings yet

- Hallucinations of Flying Caused by the Herb UchchaTADocument2 pagesHallucinations of Flying Caused by the Herb UchchaTASundara VeerrajuNo ratings yet

- Brhadaranyaka - Upanisad - PART 1 PDFDocument493 pagesBrhadaranyaka - Upanisad - PART 1 PDForchidocean5627No ratings yet

- Taxonomy For The Technology DomainDocument2 pagesTaxonomy For The Technology DomainK.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiNo ratings yet

- Reconstructing The Tree of LifeDocument1 pageReconstructing The Tree of LifeK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (1)

- Taxonomy Matching Using Background KnowledgeDocument3 pagesTaxonomy Matching Using Background KnowledgeK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (1)

- Primitive Classification Émile Durkheim and Marcel MaussDocument6 pagesPrimitive Classification Émile Durkheim and Marcel MaussK.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiNo ratings yet

- Evolutionary Ps Is Not EvilDocument22 pagesEvolutionary Ps Is Not EvilVíctor Julián VallejoNo ratings yet

- Terrizzi JR 2020 On The Origin of Shame Does Shame e PDFDocument13 pagesTerrizzi JR 2020 On The Origin of Shame Does Shame e PDFK.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiNo ratings yet

- (Systematics Association Special Volumes) Trevor R. Hodkinson, John A.N. Parnell-Reconstructing The Tree of Life - Taxonomy and Systematics of Species Rich Taxa-CRC Press (2006) PDFDocument374 pages(Systematics Association Special Volumes) Trevor R. Hodkinson, John A.N. Parnell-Reconstructing The Tree of Life - Taxonomy and Systematics of Species Rich Taxa-CRC Press (2006) PDFK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (2)

- Andrew Jotischky-A Hermit's Cookbook - Monks, Food and Fasting in The Middle Ages-Continuum (2011) PDFDocument224 pagesAndrew Jotischky-A Hermit's Cookbook - Monks, Food and Fasting in The Middle Ages-Continuum (2011) PDFK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (2)

- Lily Abegg, The Mind of East AsiaDocument365 pagesLily Abegg, The Mind of East AsiaK.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiNo ratings yet

- Subrahmanya Sastri An Alphabetical Index of Sanskrit Manuscripts in The GOML Madras v2 Biswas0633 1940Document357 pagesSubrahmanya Sastri An Alphabetical Index of Sanskrit Manuscripts in The GOML Madras v2 Biswas0633 1940K.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiNo ratings yet

- Tamil Nadu 9th Standard HistoryDocument148 pagesTamil Nadu 9th Standard HistoryIndia History ResourcesNo ratings yet

- TN Goml 03 PDFDocument342 pagesTN Goml 03 PDFK.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiNo ratings yet

- Indian Logic and Medieval Western LogicDocument425 pagesIndian Logic and Medieval Western LogicK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (2)

- Anxieties of Attachment, The Dynamics of Courtship in Medieval IndiaDocument38 pagesAnxieties of Attachment, The Dynamics of Courtship in Medieval IndiaK.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiNo ratings yet

- Hopkins, Meditating On Mere Absence (MMK Mangalasloka and Chapt.1.)Document23 pagesHopkins, Meditating On Mere Absence (MMK Mangalasloka and Chapt.1.)kaljanaNo ratings yet

- Phylosophy - Indian Logic and Medieval Western LogicDocument12 pagesPhylosophy - Indian Logic and Medieval Western LogichevenpapiyaNo ratings yet

- Asanga AbhidharmasamuccayaDocument180 pagesAsanga Abhidharmasamuccayaekavati100% (2)

- Abhidharmakosabhasyam, Vol 1, Vasubandhu, Poussin, Pruden, 1991Document430 pagesAbhidharmakosabhasyam, Vol 1, Vasubandhu, Poussin, Pruden, 1991Uanderer100% (7)

- A Glossary of Indian Figures of SpeechDocument128 pagesA Glossary of Indian Figures of SpeechK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (1)

- The Concept of A Concept A K WarderDocument17 pagesThe Concept of A Concept A K WarderK.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiNo ratings yet

- Dhvanyaloka 1Document13 pagesDhvanyaloka 1K.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiNo ratings yet

- Religion in Iran, The Parthian and Sasanian PeriodsDocument33 pagesReligion in Iran, The Parthian and Sasanian PeriodsK.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiNo ratings yet

- 6 - Sri Aurobindo's Perspective On The Future of ScienceDocument8 pages6 - Sri Aurobindo's Perspective On The Future of ScienceK.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiNo ratings yet

- Yajnavalkya Smrit DharamshastraDocument476 pagesYajnavalkya Smrit Dharamshastrakhalil_rehman_26100% (2)

- What The Cārvākas Originally Meant, More On The Commentators On The CārvākasūtraDocument15 pagesWhat The Cārvākas Originally Meant, More On The Commentators On The CārvākasūtraK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (1)

- Why Yoga, A Cultural History of YogaDocument572 pagesWhy Yoga, A Cultural History of YogaK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (1)

- Dhvanyaloka 2Document23 pagesDhvanyaloka 2K.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiNo ratings yet

- Dhvanyaloka 3Document43 pagesDhvanyaloka 3K.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiNo ratings yet

- Brahma Siddhi - By.mandana - Misra SanskritDocument643 pagesBrahma Siddhi - By.mandana - Misra SanskritGirirajPurohitNo ratings yet

- Semiotics of Ideology: Winfried No THDocument12 pagesSemiotics of Ideology: Winfried No THvoxpop88No ratings yet

- English For Translation Class 6 Module6Document13 pagesEnglish For Translation Class 6 Module6api-280202835No ratings yet

- Scan 0001Document5 pagesScan 0001Dogaru AlexandruNo ratings yet

- Baguio Uge1 9 10Document2 pagesBaguio Uge1 9 10Risha Mhie MatilaNo ratings yet

- Roman Life and Manners FriedlanderDocument344 pagesRoman Life and Manners FriedlanderGabrielNo ratings yet

- Goda KalyanamDocument2 pagesGoda KalyanamSudhakar V.Rao MDNo ratings yet

- God's Secret Signature, "The Hallelujah Menorah": The Timeline of The Tribulation in The PsalmsDocument7 pagesGod's Secret Signature, "The Hallelujah Menorah": The Timeline of The Tribulation in The PsalmsClassical_Gas100% (1)

- Erasing Narration Samuel Beckett - S Malone Dies and Texts For NothingDocument19 pagesErasing Narration Samuel Beckett - S Malone Dies and Texts For NothingMatheus MullerNo ratings yet

- Holy Spirit Rain On Us I Worship You Great I Am: ChorusDocument4 pagesHoly Spirit Rain On Us I Worship You Great I Am: ChorusMyMy MargalloNo ratings yet

- Unit-2. Structuralism & PoststructuralismDocument4 pagesUnit-2. Structuralism & PoststructuralismDr Prasath MNo ratings yet

- 4th MusterDocument23 pages4th MusterPraful ChikaniNo ratings yet

- Creative Writing Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesCreative Writing Lesson PlanNarsim SaddaeNo ratings yet

- Maimonides On The Regimen of Health: Gerrit Bos - 978-90-04-39419-3 Via Free AccessDocument550 pagesMaimonides On The Regimen of Health: Gerrit Bos - 978-90-04-39419-3 Via Free AccessMotasem HajjiNo ratings yet

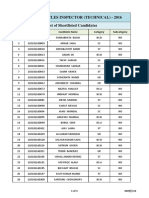

- Shortlisted Candidates for Motor Vehicles Inspector (Technical) - 2016Document3 pagesShortlisted Candidates for Motor Vehicles Inspector (Technical) - 2016Abhishek AnandNo ratings yet

- Jhuth Na Bol Pandey Sach KaheayDocument8 pagesJhuth Na Bol Pandey Sach Kaheaybanda singhNo ratings yet

- Disney's Mulan-The True Deconstructed Heroine 2000Document17 pagesDisney's Mulan-The True Deconstructed Heroine 2000Gabriel Laguna MariscalNo ratings yet

- Ncert Solutions: ClassDocument8 pagesNcert Solutions: ClassAnil Om Prakash BedwalNo ratings yet

- 4th Quarter Exam 21st CenturyDocument3 pages4th Quarter Exam 21st CenturyDonna MenesesNo ratings yet

- Epic Avatar Quiz, Bro Part IDocument11 pagesEpic Avatar Quiz, Bro Part IBecca ParsonsNo ratings yet

- Charcters, SomaDocument4 pagesCharcters, SomaCuddle BunnyNo ratings yet

- Africa Volume 44 Issue 4 1974 (Doi 10.2307 - 1159054) Bolanle Awe - Praise Poems As Historical Data - The Example of The Yoruba Oríkì PDFDocument20 pagesAfrica Volume 44 Issue 4 1974 (Doi 10.2307 - 1159054) Bolanle Awe - Praise Poems As Historical Data - The Example of The Yoruba Oríkì PDFodditrupoNo ratings yet

- KidiloDocument2 pagesKidiloNatasha MorrisNo ratings yet

- Queen Dynamis of BosporusDocument25 pagesQueen Dynamis of Bosporusruja_popova1178No ratings yet

- Fourth-Placed Video Is Undead Unluck.Document2 pagesFourth-Placed Video Is Undead Unluck.boyer klausNo ratings yet

- Mortality Vs ImmortalityDocument2 pagesMortality Vs Immortalityfarah fouadNo ratings yet

- Antigone Text - Adventures in World LitDocument32 pagesAntigone Text - Adventures in World LitRamona FlowersNo ratings yet

- Genealogy and EthnographyDocument36 pagesGenealogy and Ethnographyis taken readyNo ratings yet

- Aklat NG ProteksyonDocument54 pagesAklat NG ProteksyonJeffocks Uson100% (17)

- Notes On AbhinayadarpanamDocument6 pagesNotes On AbhinayadarpanamSkcNo ratings yet

- Purgatory P.leyshonDocument55 pagesPurgatory P.leyshonDiyei PulverizadorNo ratings yet