Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Teacher Attitudes Efl Syria

Uploaded by

ranju1978Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Teacher Attitudes Efl Syria

Uploaded by

ranju1978Copyright:

Available Formats

Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

www.elsevier.com/locate/compedu

Teachers attitudes toward information and communication

technologies: the case of Syrian EFL teachers

Abdulka Albirini

Department of Educational Policy and Leadership, Technologies of Instruction and Media Program,

203 Jennings Hall, 1735 Neil Avenue, Columbus, OH 43210, USA

Received 18 August 2004; accepted 29 October 2004

Abstract

Based on the new technology initiative in Syrian education, this study explored the attitudes of high

school English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers in Syria toward ICT. In addition, the study investigated the relationship between computer attitudes and ve independent variables: computer attributes, cultural perceptions, computer competence, computer access, and personal characteristics (including computer

training background). The ndings suggest that teachers have positive attitudes toward ICT in education.

Teachers attitudes were predicted by computer attributes, cultural perceptions and computer competence.

The results point to the importance of teachers vision of technology itself, their experiences with it, and the

cultural conditions that surround its introduction into schools in shaping their attitudes toward technology

and its subsequent diusion in their educational practice.

2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Media in education; Secondary education; Country-specic development; Pedagogical issues

1. Introduction

The last two decades have witnessed a worldwide proliferation of information and communication technologies (ICT, henceforth) into the eld of education. The global adoption of

*

Tel.: +1 614 292 9255; fax: +1 614 292 1262.

E-mail address: albirini.1@osu.edu.

0360-1315/$ - see front matter 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2004.10.013

374

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

ICT into education has often been premised on the potential of the new technological tools

to revolutionize an outmoded educational system, better prepare students for the information

age, and/or accelerate national development eorts. In developing countries in particular, the

above promises have generated a whole set of wild speculations about the necessity of educational reforms that will accommodate the new tools (Pelgrum, 2001).

Governments in most developing countries have responded to the challenge by initiating

national programs to introduce computers into education. Doing so, these governments

have added to their burden of debt even though the costs are large and the payos modest (Benzie, 1995, p. 38). Benzie indicates that national programs have been of limited success not only because they were formulated in non-educational realms, but also because

they were not based on research. In Rogers terms (1995), the initiation stage, which demands information gathering and planning, seems to be missing in this headlong process of

technology implementation. Young (1991) remarks that in many cases computers were

introduced into schools not as a means, but as an end. Computers were provided with

no supplementary measures to enable educators to develop positive attitudes toward the

new tools and to use them. This has often resulted in ad hoc approaches to implementation. In this approach, technology availability is mistaken for technology adoption and use.

However, As Baylor and Ritchie (2002) state, regardless of the amount of technology and

its sophistication, technology will not be used unless faculty members have the skills,

knowledge and attitudes necessary to infuse it into the curriculum (p. 398). That is, teachers should become eective agents to be able to make use of technology in the classroom.

Ultimately, teachers are the most important agents of change within the classroom

arena.

One developing country that is currently pursuing the technological track in education is

the Syrian Arab Republic. Recognizing the challenge of the information age, the Syrian

Ministry of Education has recently adopted a national plan to introduce computers and

informatics into pre-college education. To this end, the Ministry has inaugurated computerequipped labs within secondary schools for general, vocational and technical education. It

has also connected many schools to the Internet. In addition, the Ministry created a new specialization in computer technologies in an eort to increase the number of computer experts

in society. According to The National Report (2000), the introduction of technology into the

Syrian educational system aims to keep pace with the progress and to reach ecient levels

of education.

Unfortunately, the implementation of technology into the Syrian schools has not been guided

by research. This has often been the case in most countries across the world. In particular, the

technology implementation plans seem to be lacking consideration of teachers reaction to the

new tools. Such inattention to the end-users attitudes may engender unforeseen repercussions

for ICT diusion in Syrian schools. In his theory of Diusion of Innovations, Rogers (1995) considers adopters attitudes indispensable to the innovation-decision process. A number of studies

have shown that teachers attitudes toward computers are major factors related to both the initial

acceptance of computer technology as well as future behavior regarding computer usage (Koohang, 1989; Selwyn, 1997). This suggests that studies at the early stages of technology implementation should focus on the end-users attitudes toward technology. The current study was based on

this pressing need.

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

375

2. Review of the literature

As a recent educational innovation, the computerization of education is a complex process

where many agents play a role. Forces at the micro-level of the educational system (teachers

and students) may be inuential in facilitating or impeding changes that are outside the control

of the ministries of education (Pelgrum, 2001). Unfortunately, much of the early research on computer uses in education has ignored teachers attitudes toward the new machines (Harper, 1987).

Studies focused on the computer and its eect on students achievement, thus overlooking the psychological and contextual factors involved in the process of educational computerization (Clark,

1983; Thompson, Simonson, & Hargrave, 1992).

Recent studies have shown that the successful implementation of educational technologies depends largely on the attitudes of educators, who eventually determine how they are used in the

classroom. Bullock (2004) found that teachers attitudes are a major enabling/disabling factor

in the adoption of technology. Similarly, Kersaint, Horton, Stohl, and Garofalo (2003) found that

teachers who have positive attitudes toward technology feel more comfortable with using it and

usually incorporate it into their teaching. In fact, Woodrow (1992) asserts that any successful

transformation in educational practice requires the development of positive user attitude toward

the new technology. The development of teachers positive attitudes toward ICT is a key factor

not only for enhancing computer integration but also for avoiding teachers resistance to computer use (Watson, 1998). Watson (1998) warns against the severance of the innovation from

the classroom teacher and the idea that the teacher is an empty vessel into which this externally

dened innovation must be poured (p. 191).

According to Rogers (1995), peoples attitudes toward a new technology are a key element in its

diusion. Since Rogers uses the terms innovation and technology interchangeably (p. 12), the diffusion of innovation framework seems particularly suited for the study of the diusion of ICT.

Rogers Innovation Decision Process theory states that an innovations diusion is a process that

occurs over time through ve stages: Knowledge, Persuasion, Decision, Implementation and Conrmation. Accordingly, the innovation-decision process is the process through which an individual (or other decision-making unit) passes (1) from rst knowledge of an innovation, (2) to forming

an attitude toward the innovation, (3) to a decision to adopt or reject, (4) to implementation of the

new idea, and (5) to conrmation of this decision (Rogers, 1995, p. 161). Due to the novelty of

computers and their related technologies, studies concerning technology diusion in education

have often focused on the rst three phases of the innovation decision process. This is also because

the status of computers in education is, to a great extent, still precarious. In cases where technology

is very recently introduced into the educational system, as is the case of most developing countries,

studies have mainly focused on the rst two stages, that is, on knowledge of an innovation and attitudes about it.

Rogers premise concerning individuals shift from knowledge about technology to forming attitudes toward it and then to its adoption or rejection corroborates the general and widely accepted

belief that attitudes aect behavior directly or indirectly (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Zimbardo, Ebbesen, & Maslach, 1977). Teachers attitudes have been found to be a major predictor of the use of

new technologies in instructional settings (Abas, 1995b; Blankenship, 1998; Isleem, 2003). Christensen (1998) states that teachers attitudes toward computers aect not only their own computer

experiences, but also the experiences of the students they teach. In fact, it has been suggested that

376

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

attitudes towards computers aect teachers use of computers in the classroom and the likelihood

of their beneting from training (Kluever, Lam, Homan, Green, & Swearinges, 1994). Positive

attitudes often encourage less technologically capable teachers to learn the skills necessary for

the implementation of technology-based activities in the classroom.

Knezek and Christensens (2002) analysis of several major cross-cultural studies completed during the 1990s and related to ICT in education suggests that teachers advance in technology integration through a set of well dened stages, which sometimes require changes in attitude more so

than skills. According to Zimbardo et al. (1977), changing individuals behavior is possible once

their attitudes have been identied. Zimbardo and his associates suggest that attitudes are made

up of three components: aect, cognition, and behavior. The aective component represents an

individuals emotional response or liking to a person or object. The cognitive component consists

of a persons factual knowledge about a person or object. Finally, the behavioral component involves a person overt behavior directed toward a person or object (p. 20). Zimbardo et al. contend that even though we cannot predict the behavior of single individuals, we should be able to

predict that people (in general) will change their behavior if we can change their attitudes. . . (p.

52). The latter assertion explains to a large extent the wide interest in the study of the attitudes

toward technology.

Unfortunately, the task of pinning down teachers attitudes has not always been an easy one.

Watson (1998) considers teachers attitudes as the most misread impeding force in the integration

of computers in educational practices. As Zimbardo et al. (1977) note, the complexity of attitudes

and their interrelationship with behavior and many other variables summons a considerations for

the maze of variables and processes that could aect attitudes, beliefs, and action (p. 53). Studies have pointed to a wide range of factors aecting attitudes toward ICT. The variations in the

factors identied by dierent researchers might be attributed to dierences in context, participants, and type of research.

One of the major factors aecting peoples attitudes toward a new technology is the attributes of the technology itself (Rogers, 1995). Rogers identied ve main attributes of technology that aect its acceptance and subsequent adoption: relative advantage, compatibility,

complexity, observability, and trialibility. Thus, a new technology will be increasingly diused

if potential adopters perceive that the innovation: (1) has an advantage over previous innovations; (2) is compatible with existing practices, (3) is not complex to understand and use, (4)

shows observable results, and (5) can be experimented with on a limited basis before adoption.

In this study, computer attributes was operationally dened as the level of relative advantage,

compatibility, complexity, and observability of the computers as perceived by high school English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers in Syria. Trialibility was not examined because

the majority of Syrian teachers may not have had the chance to experiment with computers

before these were introduced into schools. Rogers and Shoemaker (1971) found that relative

advantage, compatibility and observability were positively related to adoption, whereas complexity was negatively correlated. In his study in Trinidad and Togo, Sooknanan (2002) found

that relative advantage, compatibility, and observability were signicantly related to the teachers attitudes toward computers. However, the results showed no relationship between complexity and teachers attitudes.

Rogers (1995) and Thomas (1987) emphasized the importance of the cultural/social norms of a

given country to the acceptance of technology among its people. Potential adopters may resist a

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

377

technological tool because it may not t within their micro- or macro-cultures. Thomas proposes,

How acceptable a new technology will be in a society depends on how well the proposed innovation ts the existing culture (p.15). Thomas refers to his hypothesis as the cultural suitability

factor. Both Rogers (1995) and Thomas (1987) note that few studies have considered the inuence

of peoples cultural perceptions on their adoption of technological innovations. In this study,

Cultural Perceptions was operationally delineated to mean Syrian EFL teachers perceptions

of the value, relevance, and impact of ICT as it relates to the cultural norms in Syrian society and

schools. Among the very few researchers examining cultural norms, Li (2002) explored the eects

of national culture on students use of the Internet and the dierences between Chinese and British

students in terms of use of the Internet. The researcher found that there were dierences in Internet experience, attitudes, usage, and competence between Chinese and British students. Most of

these dierences were related to students national culture.

In addition to computer attributes and cultural norms, previous research suggests that teachers

attitudes toward computer technologies are also related to teachers computer competence. In

their study of the correlation between teachers attitude and acceptance of technology, FrancisPelton and Pelton (1996) maintained, Although many teachers believe computers are an important component of a students education, their lack of knowledge and experience lead to a lack of

condence to attempt to introduce them into their instruction (p. 1). In this study, computer

competence was operationalized to mean Syrian EFL teachers perceptions about their computer

knowledge and computer skills as measured by the instrument developed for this study. A large

number of studies showed that teachers computer competence is a signicant predictor of their

attitudes toward computers (Berner, 2003; Na, 1993; Summers, 1990). Al-Oteawi (2002) found

that most teachers who showed negative or neutral attitudes toward the use of ICT in education

lacked knowledge and skill about computers that would enable them to make informed decision (p. 253).

Most studies examining computer attitudes have also reported a signicant association between

computer access and teachers attitudes toward computers (Na, 1993; Pelgrum, 2001). In his study

of Korean teachers, Na (1993) found a positive correlation between teachers attitudes toward computers and computer ownership, accessibility to school computers, the level of accessibility to

school computers, and number of computer locations in the school. Na concluded that there was

a signicant relationship between the proximity of computers and the number of access resources

(home and school) on the one hand, and, on the other, teachers attitudes toward computers.

3. The study

Given the importance of teachers attitudes and the relationship of teachers attitudes to the

above variables, the purpose of this study was therefore to determine the high school EFL teachers attitudes toward ICT in Syrian education and then to explore the relationship between teachers attitudes and factors that are thought to be inuencing them, including perceived computer

attributes, cultural perceptions, perceived computer competence, and perceived computer access.

Teachers personal characteristics (gender, age, income, teaching experience, school location, education, and teaching methods as well as computer training background) were also included in order to ensure maximum possible control of extraneous variables by building them into the design

378

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

of the study (Gay & Airasian, 2000). More specically, the study investigated the following

questions:

1. What are the attitudes of high school EFL teachers in Syria toward ICT in education?

2. What are the teachers perceptions of:

a. Computer attributes?

b. Cultural relevance of computers to Syrian society and schools?

c. Their level of computer competence?

d. Their level of access to computers?

3. What is the proportion of the variance in the attitudes of teachers toward ICT in education

that can be explained by the selected independent variables (as well as teachers personal characteristics) and the relative signicance of each independent variable in explaining the dependent variable?

The study focused mainly on EFL teachers because they were rst to experiment with computers in the Syrian context. This is partly because of their familiarity with English as the main computer language and also because much of the available software is for English language practice.

Moreover, The eld of foreign language education has always been in the forefront of the use of

technology to facilitate the language-acquisition process (Laord & Laord, 1997, p. 215).

4. Methodology

This was a descriptive study of an exploratory nature. Creswell (2003) suggests that exploratory

studies are most advantageous when not much has been written about the topic or the population

being studied (p. 30). The target population in this study was high school EFL teachers in Hims

(the largest Syrian province) during the 20032004 school year. The list of teachers was based on

EFL teachers Directory, which is maintained and updated on a quarterly basis by Hims Department of Education. The total number of high school EFL teachers in the Directory of the Department of Education was 887 (214 males, 24%; 673 females, 76%) as of the 30th of March, 2004.

A simple random sample of 326 subjects was selected to participate in the study. The specic procedure used for sample selection was a table of random numbers (Gay & Airasian, 2000, p. 124).

This procedure involved assigning each subject in the population to a number, and then selecting

326 arbitrary numbers from the population. Since each number corresponded to a subject in the

population, the selected numbers formed the sample of subjects for the study.

Due to dierences between the participants and cultural context of this study and those in previous studies, a questionnaire was developed by the researcher to obtain the information needed for

the study rather than using existing instruments. The development of questionnaire was guided by

extensive review of literature and scales used in dierent educational backgrounds (Al-Oteawi,

2002; Bannon, Marshall, & Fluegal, 1985; Bear, Richards, & Lancaster, 1987; Christensen & Knezek, 1996; Gardner, Discenza, & Dukes, 1993; Gressard & Loyd, 1986; Harrison & Rainer, 1992;

Isleem, 2003; Jones & Clarke, 1994; Meier, 1988; Na, 1993; Robertson, Calder, Fung, Jones, &

OShea, 1995; Sooknanan, 2002; Swadener & Hannan, 1987). The questionnaire consisted of

six scales that correspond to the main variables of the study (Appendix A). The instrument was

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

379

evaluated by a panel of experts for content and face validity. The panel included three content experts (Professors of educational technology and EFL), two bilingual experts, one measurement expert, and four population experts (Syrian EFL teachers). Feedback from the panel of experts was

used mainly to ensure that the six scales measure the content areas of investigation and are culturally and technically appropriate for the context of the study. The Cronbachs a reliability coecients for the rst four scales were: computer attitude = 0.90, computer attributes = 0.86,

cultural perceptions = 0.76, and computer competence = 0.94. The computer access scale consisted

of three statements that took into account possible locations where computers might be available

for use by EFL teachers: at home, in school, and other places. Demographic variables were quantied by individual scores on eight items. The responses to all eight items were treated separately as

descriptive information that was correlated with the attitudes toward ICT. The questionnaire was

translated into Arabic and then back into English to ensure its suitability for the participants.

Following Dillmans (1978) recommendations, a letter of recruitment, a letter of informed

consent, and a return envelope accompanied the questionnaire. Letters of support by the Syrian Ministry of Education and the Director of English in the Department of Education were

used for accessing the schools and teachers. A total of 326 questionnaires were distributed

over a period of three days from the 27th to the 29th of April, 2004. The questionnaires were

delivered in person to school principals of each participant or group of participants (when two

or more sample teachers were from the same school). Principals in turn distributed them to

the teachers. Three days before the deadline, school principals were asked via phone to remind

teachers to complete the questionnaire. The questionnaires and the accompanying forms were

collected in person from school principals from May 12th to May 14th. The principals of six

schools where some teachers did not complete questionnaires were asked for a three-day

extension for collecting the rest of the questionnaires from teachers. By May 17th, a total

of 320 questionnaires were collected from the participants. The response rate was 98.16%.

The rate was high enough to avoid further survey distribution. Six out of 320 were not usable

for data analysis because they were not completed. Only 314 were analyzed, representing a

valid response rate of 96.32%. The data were analyzed via SPSS. 12 statistical package.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe and summarize the properties of the mass of data

collected from the respondents (Gay & Airasian, 2000, p. 437). Multiple regression analysis

was used to determine the proportion of the variance in the attitudes of teachers toward

ICT in education that could be explained by the selected independent variables and the relative signicance of each in explaining the dependent variable. By convention, an a level of 0.05

was established a priori for determining statistical signicance. Prior to conducting the analysis, the scoring of all negatively stated items was reversed.

5. Main ndings

5.1. Research question one: teachers attitudes toward ICT in education

Participants were asked to respond to 20, Likert-type statements dealing with their attitudes

toward ICT in education (Appendix A). The items were designed to measure the aective domain

of computer attitude (items 16), cognitive domain (items 715), and behavioral domain (items

380

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

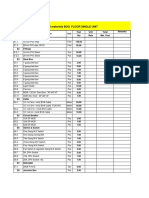

Table 1

Distribution of mean scores on the attitude toward ICT scale

Scale

Percent (%)

Mean

SD

SD

SA

Aect

Cognition

Behavior

0.3

0.0

0.3

0.6

1.0

2.9

13.7

12.4

8.3

62.4

65.9

58.3

22.9

20.7

30.3

4.00

4.05

4.13

0.5

0.4

0.5

Overall attitude

0.0

0.6

11.8

65.0

22.6

4.05

0.38

SD, strongly disagree (1); D, disagree (2); N, neutral (3); A, agree (4); SA, strongly agree (5).

1520). Computer attitudes of EFL teachers was represented by a mean score on a 5-point scale,

where 5 (Strongly Agree) represents the maximum score of the scale and 1 (Strongly Disagree)

represents the minimum score. Table 1 illustrates the distribution of mean scores on the Attitude

toward ICT scale.

As Table 1 illustrates, teachers overall attitudes toward ICT were positive with an overall

mean score of 4.05 (SD = 0.38). The respondents positive attitudes were evident within the

aective (mean = 4.00), cognitive (mean = 4.05) and behavioral (mean = 4.13) domains.

Eighty-ve point three percent (85.3%) of the respondents had positive (62.4%) or highly positive (22.9%) aect toward computers. These respondents reported that they had no apprehension of computers, were glad about the increase of computers, considered using computers

enjoyable, felt comfortable about computers, and liked to talk with others about computers

and to use them in teaching. Within the cognitive domain, most of the respondents agreed

(69.9%) and strongly agreed (20.7%) that computers save time and eort, motivate students

to do more study, enhance students learning, are fast and ecient means of getting information, must be used in all subject matters, make schools a better place, are worth the time spent

on learning them, are needed in the classroom, and generally do more good than harm. In the

behavioral domain, the majority of the respondents expressed positive (58.3%) or highly positive

(30.3%) behavioral intentions in terms of buying computers, learning about them, and using

them in the near future.

5.2. Research question two: teachers perceptions in terms of factors related to attitudes toward ICT

5.2.1. Computer attributes

Participants were asked to respond to 18, Likert-type statements dealing with their perceptions

about the relative advantage of computers (items 15), their compatibility with teachers current

practices (items 610), their simplicity/non-complexity (items 1114), and their observability

(items 1518). Overall, respondents perceptions of computers attributes were somewhat positive

with an overall mean score of 3.7 (SD = 0.38) (Table 2).

Respondents positive perceptions varied across the four computer attributes examined in

this study. Teachers responses were most positive about the relative advantage of computers

as an educational tool (mean = 4.04; SD = 0.59). Less positive were teachers perceptions of

the compatibility of computers with their current practices (mean = 3.54; SD = 0.54). While

the majority of respondents indicated that computer use suits their students learning prefer-

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

381

Table 2

Distribution of mean scores on the computer attributes scale

Scale

Percent (%)

Mean

SD

SD

SA

Advantage

Compatibility

Complexity

Observability

0.3

0.3

0.0

0.0

1.0

2.6

4.8

3.8

12.7

43.0

36.9

28.3

64.7

51.0

51.3

51.3

21.3

3.2

7.0

16.6

4.04

3.54

3.48

3.70

0.59

0.54

0.67

0.68

Overall attributes

0.0

1.3

29.0

64.4

5.4

3.70

0.38

SD, strongly disagree (1); D, disagree (2); N, neutral (3); A, agree (4); SA, strongly agree (5).

ences and level of computer knowledge and is appropriate for many language learning activities, most of them were uncertain about whether or not computer use ts well in their curriculum goals, and the majority reported that class time is too limited for computer use.

Similarly, teachers perceptions of the simplicity of computers (i.e., complexity before the

negative items were reversed) were also midway between neutral and positive (mean = 3.48;

SD = 0.67). Most of the teachers responses were split between positive and neutral about

whether it is easy to understand the basic functions of computers, operate them, and use them

in teaching. Lastly, teachers responses on the observability subscale indicate somewhat positive perceptions (3.70, SD = 0.68). Most of the respondents reported that they had seen computers at work and as educational tools in general and in the Syrian educational context in

particular.

5.2.2. Cultural perceptions

In general, participants responses to the 16 items on the Cultural Perceptions scale were somehow midway between neutral and positive (mean = 3.38, SD = 0.44) (Table 3). The majority of the

respondents had positive (64.7%) or highly positive (21.3%) perceptions about the relevance of

ICT to Syrian society and schools. Notably, most of the respondents indicated that students need

to know how to use computers for their future jobs. Moreover, most of them stated that computers will contribute to improving their standard of living and that knowing about computers earns

one the respect of others and ensures privileges not available to others. In addition, the majority

of the respondents indicated that computers do not increase their dependence on foreign countries, dehumanize society, or encourage unethical practices.

However, the fact that respondents saw ICT as culturally appropriate for Syrian schools and

society did not prevent them to indicate that there are other social issues that need to be addressed

Table 3

Distribution of mean scores on the cultural perceptions scale

Scale

Percent (%)

SD

SA

Cultural perceptions

0.3

1.0

12.7

64.6

21.3

SD, strongly disagree (1); D, disagree (2); N, neutral (3); A, agree (4); SA, strongly agree (5).

Mean

SD

3.38

0.44

382

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

Table 4

Distribution of mean scores on the computer competence scale

Scale

Computer competence

Percent (%)

No

competence

Little

competence

Moderate

competence

Much

competence

43.3

39.5

16.6

0.6

Mean

SD

1.78

0.67

before implementing computers in education, that computers are proliferating too fast, and that

alternative computers which better suit the Arabic culture and identity are needed.

5.2.3. Computer competence

Computer competence was represented by a mean score on a 4-point, scale ranging from 1 (no

competence) to 4 (much competence). Table 4 illustrates the distribution of mean scores on the 15item computer competence scale.

The majority of the respondents had no (43.3%) or little (39.5%) computer competence in handling most of the computer functions needed by educators. Sixteen point six (16.6%) of the

respondents had moderate computer competence, and less than one% (0.6%) possessed much

competence. On average, the respondents reported that they had Little Competence

(mean = 1.78; SD = 0.67) in computer uses, including software installation, printer usage, productivity software, telecommunication resources, basic troubleshooting, graphic application, grade

keeping, educational software evaluation, organization tools, and virus removal.

5.2.4. Computer access

Participants were asked to rate their level of access to potential computer places: at home,

school and other places. Computer access of EFL teachers was represented by a mean score on

a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Daily) (Table 5).

As Table 5 illustrates, Home was the respondents most frequent place of computer access

with 57 (57%; n = 179) of them having access to it either daily (30.6%; n = 96), biweekly or three

times a week (9.6%; n = 30), weekly (7.6%; n = 24), or monthly (9.2%; n = 29). Schools came second with 33.4 (33.4%; n = 105) of the respondents having access to it either daily (5.1%; n = 16),

biweekly or three times a week (4.5%; n = 14), weekly (7.3%; n = 23), or monthly (16.6%; n = 52).

Only 25.5 (25.5%; n = 80) of the respondents had access to computers in places other than home

Table 5

Distribution of mean scores on the computer access scale

Scale

Percent (%)

Never

Once a month

Home

School

Other (cafes, friends, relatives,

university, work)

43.0

66.6

74.5

9.2

16.6

11.8

Overall access level

40.8

34.7

Once a week

Mean

SD

23 Times a week

Daily

7.6

7.3

7.0

9.6

4.5

4.1

30.6

5.1

2.5

2.75

1.65

1.48

1.76

1.12

0.97

17.5

6.7

0.3

1.96

0.86

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

383

and school. These places included Internet cafes, friends, relatives, university, and private work.

The mean score on the Computer Access scale was 1.96 (SD = 0.86), which indicates that a typical

teacher had access to computers almost once a month.

5.3. Research question three: proportion of variance in teachers attitudes explained by the

independent variables

To determine the proportion of the variance in the attitudes of teachers toward ICT in education that could be explained by the selected independent variables, a multiple regression

analysis was performed. Following Gay and Airasians (2000) recommendations, simple correlations (using Pearson and Spearman analyses) were rst performed to identify independent

variables that individually correlate with the dependent variable (attitudes toward ICT). These

variables were used in the multiple regression equation to make a more accurate prediction of

the dependent variable and to show the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the selected independent variables. The independent variables that individually correlated with the dependent variable were: computer attributes (r = 0.74, p < 0.05), cultural

perceptions (r = 0.62, p < 0.05), computer competence (r = 0.30, p < 0.05), computer access

(r = 0.17, p < 0.05), and computer training (r = 0. 15, p < 0.05). Spearman rank correlations

yielded no signicant relationships between teachers attitudes and any of the demographic

variables (with the exception of computer training background). The summary of the multiple

regression results are presented in Tables 6 and 7. The results indicated that 58% of the variance in computer attitude was explained by the independent variables included in this study

(Table 6). The test statistic was signicant at the 0.05 level of signicance (F(5, 313) = 87.94;

p < 0.001).

As Table 7 illustrates, the results of multiple regression indicate that three variables aect the

teachers attitudes toward ICT at the 0.05 level of signicance. The following are the absolute

Table 6

Analysis of variance

Sources

Sum of squares

DF

Mean square

F value

R2

Adjusted R2

Model

Error

47.10

33.00

5

308

9.41

0.11

87.94

0.59

0.58

<0.001

Total

80.03

313

Table 7

Multiple regression on dependent variable (computer attitude)

Variable

Unstandardized b

Standardized b

Computer attributes

Cultural perceptions

Computer competence

Computer access

Training

0.60

0.29

0.07

0.04

0.02

0.57

0.25

0.10

0.06

0.03

11.03

5.02

2.18

1.50

0.71

<0.001

<0.001

0.030

0.14

0.481

384

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

values of the standardized estimate (b) of these factors from largest to smallest: computer attributes (b = 0.57, t = 11.03, p < 0.05), cultural perceptions (b = 0.25, t = 5.02, p < 0.05), and

computer competence (b = 0.10, t = 2.18, p < 0.05). The analysis suggests that the independent

variables explaining the greatest amount of variance in computer attitudes are in order of

predicative value: computer attributes, cultural perceptions, and computer competence

(Table 7).

6. Discussion

The study investigated the attitudes of high school EFL teachers in a large Syrian province

toward ICT and the relationship of teachers attitudes to a selected set of independent variables. Teachers attitudes toward ICT have been universally recognized as an important factor

for the success of technology integration in education (Rogers, 1995; Watson, 1998; Woodrow,

1992). Findings from this study suggest that participants had positive attitudes toward ICT in

education. The respondents positive attitudes were evident within the aective, cognitive and

behavioral domains. Such optimism cannot simply be attributed to the novelty of computers

in Syrian education (Salaberry, 2001). The participants seemed to have totally accepted the

rationale for introducing ICT into schools and were able to base their judgments on understandable reasons. Thus, the majority of respondents considered computers as a viable educational tool that has the potential to bring about dierent improvements to their schools and

classrooms.

Teachers positive attitudes exhibit their initiation into the innovation-decision process (Rogers,

1995). It seems that teachers have already gone through the Knowledge and Persuasion stages

(Rogers, 1995) and are probably proceeding to the Decision phase. As many theorists have indicated, attitudes can often foretell future decision-making behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). Having formed positive attitudes toward ICT in education, participants are expected to be using ICT

in their classrooms once computers become more available to them. In fact, the behavioral subscale of the computer attitude scale showed that the majority of teachers had the intention to learn

about computers and to use them in the near future. This symbiotic relationship between attitudes

toward ICT and its use in the classroom has been widely reported in the literature (e.g., Blankenship, 1998; Isleem, 2003).

The ndings of the study indicated a very strong positive correlation between teachers attitudes toward ICT in education and their perceptions of computer attributes. The ndings are

consistent with Rogers Innovation Attributes sub-theory. An examination of individual computer attributes shows that respondents were most positive about the relative advantage of

computers as an educational tool. However, teachers perceptions of the compatibility of

ICT with their current teaching practices were not as positive. The majority of them were

uncertain about whether or not computers t well in their curricular goals. The disparity between technological demands and the existing curricula has often been a major hindrance for

technology integration (Ojo & Awuah, 1998). As the responses of the participants indicate,

the Syrian educational landscape seems to be no exception. Besides, most of the participants

considered that the class time is too limited for computer use. This problem has also been

emphasized in the literature (Becker, 1998). Teachers concerns about the incompatibility of

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

385

computers with the existing curricula as well as the lack of time for computer use indicate

that educational change cannot simply be attained by placing computers in schools (Hodas,

1993). For a change to occur, many renovations need to be made at the structural level as

well as the pedagogic level. Otherwise, a consistent mismatch will occur between the industrial

models of schooling and the information-age teaching/learning devices. Salamon (2002) refers

to this mismatch as a Technological Paradox resulting from the consistent tendency of the

education system to preserve itself and its practices by the assimilation of new technologies

into existing instructional practices (pp. 7172). Hence, the introduction of ICT innovations

into education requires equal innovativeness in structural, pedagogical and curriculum

approaches.

Interestingly, cultural perceptions were the second most important predictor of computer attitudes in this study. This conclusion points to the need for considering cultural factors in studies

conducted in developing countries. The majority of respondents regarded computers as pertinent to both Syrian schools and society and viable means for improving education and standards of living in general. What should not go unnoticed, however, is that the majority of

the respondents felt the need for computers that better suit the Arabic culture and identity.

It has often been noted that people who have not been quite inuential in the design and development of ICT would prefer a localized version of these technologies (Damarin, 1998). In addition, many of the respondents saw that there are more important social issues to be addressed

before implementing computers in education. Therefore, it was not a surprise that almost all of

the respondents agreed that computers are proliferating too fast. The above conclusion implies

that balancing resource allocation among the competing areas of need is a critical issue in developing countries.

Previous research has pointed to teachers lack of computer competence as a main barrier to

their acceptance and adoption of ICT in developing countries (Al-Oteawi, 2002; Na, 1993; Pelgrum, 2001). The results of the current study support and extend the ndings from previous

research. The majority of respondents reported having little or no competence in handling most

of the computer functions needed by educators. This nding did not support the assumption

that teachers with low level of computer competence usually have negative attitudes toward

computers (Summers, 1990). On the other hand, the fact that computer competence was significantly related to teachers attitudes supports the theoretical and empirical arguments made for

the importance of computer competence in determining teachers attitudes toward ICT (Al-Oteawi, 2002; Berner, 2003; Bulkeley, 1993; Na, 1993). In addition, the relationship between computer attitudes and competence suggests that higher computer competence may foster the

already positive attitudes of teachers and eventually result in their use of computers within

the classroom.

Computer access has often been one of the most notorious impediments to technology adoption

and integration worldwide (Abas, 1995a; Pelgrum, 2001). Findings from the current study substantiate this globally felt barrier. While a relatively high percentage of the respondents (57%)

had computers at home, only 33.4% of the respondents had access to computers at school. The

latter percentage gives a clear indication of the insuciency of computers at schools, particularly

for teacher use. As noted above, the paucity of computer resources available for teachers has been

widely reported in the literature as a major obstacle to technology integration in education (e.g.,

Abas, 1995a; Na, 1993). Although the shortage of computers did not seem to have notable impact

386

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

on the teachers attitudes toward ICT in this study, it may theoretically have its eects on their

future uses of ICT in the classroom.

7. Conclusion

Given the recent presence of technology in their schools, developing countries have the responsibility not merely to provide computers for schools, but also to foster a culture of acceptance

amongst the end-users of these tools. Hence, the study of teachers attitudes becomes indispensable to the technology implementation plans. As Sheingold (1991, cited in North Central Regional

Educational Laboratory, 2003) notes, the challenge of technology integration into education is

more human than it is technological.

The ndings of this study may be specic to EFL teachers in Syrian education, but their implications are signicant to other educators as well. Teachers positive attitudes in the current study

have a special signicance given the limitations characterizing the current status of ICT in Syrian

schools: insucient computer resources and teachers lack of computer competence. It is therefore

essential for policy-makers to sustain and promote teachers attitudes as a prerequisite for deriving

the benets of costly technology initiatives. Since positive attitudes toward ICT usually foretell

future computer use, policy-makers can make use of teachers positive attitudes toward ICT to

better prepare them for incorporating ICT in their teaching practices.

One of the main barriers to technology implementation perceived by the teachers in this study is

the mismatch between ICT and the existing curricula and the class-time frame. It follows that

placing computers in schools is not enough for attaining educational change. The introduction

of ICT into education requires equal innovativeness in other aspects of education. Both policymakers and teachers share this responsibility. Policy-makers should provide additional planning

time for teachers to experiment with new ICT-based approaches. This may be attained by reducing the teaching load for the teachers.

Other barriers reported in this study were teachers low level of access to school computers,

which may have played a role in teachers modest computer competence so essential to future

computer use. Such conclusion points to the invariable importance of technology resources for

the success of technology initiatives across the world. This also implies that technology initiatives

should include measures for preparing teachers to use computers in their teaching practices.

Teachers preparation necessitates not merely providing additional training opportunities, but

also aiding them in experimenting with ICT before being able to use it in their classrooms. If decision-makers want to involve teachers in the process of technology integration, they have to nd

ways to overcome the barriers perceived by the teachers.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my indebtedness for the participants who gave me their time to complete

the surveys. I am also grateful for my brother Ahmad, who facilitated much of the contacts with

the Ministry of Education, the Department of Education, principals, and teachers. I am thankful

to Mr. Nibhan Addakar, the Director of English in the Department of Education, for his kind

contribution to the completion of the study.

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

Appendix A. Study instrument (Arabic version)

387

388

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

389

390

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

Appendix B. Study instrument (English version)

The Ohio State University Attitudes toward Computer Technology

General Instructions: The purpose of this questionnaire is to examine your attitudes toward the

introduction of information technology into Syrian education. The questionnaire consists of six

sections. Each section begins with some directions pertaining to that part only. As you begin each

section, please read the directions carefully and provide your responses candidly in the format

requested.

Section (1): Instructions: Please indicate your reaction to each of the following statements by

circling the number that represents your level of agreement or disagreement with it. Make sure

to respond to every statement.

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

Computers do not scare me at

all

Computers make me feel

uncomfortable

I am glad there are more

computers these days

I do not like talking with

others about computers

Using computers is enjoyable

I dislike using computers in

teaching

Computers save time and

eort

Schools would be a better

place without computers

Students must use computers

in all subject matters

Learning about computers is a

waste of time

Computers would motivate

students to do more study

Computers are a fast and

ecient means of getting

information

I do not think I would ever

need a computer in my

classroom

Computers can enhance

students learning

Computers do more harm

than good

I would rather do things by

hand than with a computer

If I had the money, I would

buy a computer

I would avoid computers as

much as possible

I would like to learn more

about computers

I have no intention to use

computers in the near future

391

Strongly

disagree

Disagree

Neutral

Agree

Strongly

agree

1

1

2

2

3

3

4

4

5

5

392

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

Section (2) Instructions: Please indicate your reaction to each of the following statements by

circling the number that represents your level of agreement or disagreement with it. Make sure

to respond to every statement

1

2

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

Computers will improve

education

Teaching with computers

oers real advantages over

traditional methods of

instruction

Computer technology cannot

improve the quality of

students learning

Using computer technology in

the classroom would make the

subject matter more

interesting

Computers are not useful for

language learning

Computers have no place in

schools

Computer use ts well

into my curriculum

goals

Class time is too limited for

computer use

Computer use suits my

students learning preferences

and their level of computer

knowledge

Computer use is appropriate

for many language learning

activities

It would be hard for me to

learn to use the computer in

teaching

I have no diculty in

understanding the basic

functions of computers

Computers complicate my

task in the classroom

Strongly

disagree

Disagree

Neutral

Agree

Strongly

agree

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

393

Appendix B (continued)

14

15

16

17

18

Everyone can easily learn to

operate a computer

I have never seen computers

at work

Computers have proved to be

eective learning tools

worldwide

I have never seen computers

being used as an educational

tool

I have seen some Syrian

teachers use computers for

educational purposes

Strongly

disagree

Disagree

Neutral

Agree

Strongly

agree

Section (3) Instructions: Please indicate your reaction to each of the following statements by

circling the number that represents your level of agreement or disagreement with it. Make sure

to respond to every statement

Strongly Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly

disagree

agree

1 Computers will not make any dierence in

our classrooms, schools, or lives

2 Students need to know how to use

computers for their future jobs

3 Students prefer learning from teachers to

learning from computers

4 Knowing about computers earns one the

respect of others

5 We need computers that suit better the

Arabic culture and identity

6 Computers will improve our standard of

living

7 Using computers would not hinder Arab

generations from learning their traditions

8 Computers are proliferating too fast

9 People who are skilled in computers have

privileges not available to others

10 Computers will increase our dependence

on foreign countries

1

1

2

2

3

3

4

4

5

5

(continued on next page)

394

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

Appendix B (continued)

11

12

13

14

15

16

There are other social issues that

need to be

addressed before implementing

computers in education

The increased proliferation of

computers will

make our lives easier

Computers dehumanize society

Working with computers does not

diminish people

relationships with one other

Computers encourage unethical

practices

Computers should be a priority

in education

Strongly

disagree

Disagree

Neutral

Agree

Strongly

agree

1

1

2

2

3

3

4

4

5

5

Section (4) Instructions: Please indicate your current computer competence level (i.e., both your

knowledge of and your skill in using computers) regarding each of the following statements. Make

sure to respond to every statement

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Install new software on a

computer

Use a printer

Use a computer keyboard

Operate a word processing

program (e.g., Word)

Operate a presentation

program (e.g., PowerPoint)

Operate a spreadsheet

program (e.g., Excel)

Operate a database program

(e.g., Access)

Use the Internet for

communication (e.g., email &

chatroom)

Use the World Wide Web to

access dierent types of

information

No

competence

Little

competence

Moderate

competence

Much

competence

1

1

1

2

2

2

3

3

3

4

4

4

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

395

Appendix B (continued)

10

11

12

13

14

15

Solve simple problems in

operating computers

Operate a graphics program

(e.g., Photoshop)

Use computers for grade

keeping

Select and evaluate

educational software

Create and organize computer

les and folders

Remove computer viruses

No

competence

Little

competence

Moderate

competence

Much

competence

Section (5) Instructions: Please identify how often you have computer access in the following

contexts:

1

2

3

In your home

At school (computer lab

or library)

Other (like Internet

cafes, etc.)

Daily

2 or 3

times a week

Once a week

Once a month

Never

1

1

2

2

3

3

4

4

5

5

Section (6) Instructions: Please indicate you response to the following questions by checking the

appropriate boxes:

1 What is your genderh Male h Female

2 What is your age? h 2029 h 3039 h 4049 h 5059 h60 and over

3 What is your monthly average household income in Syrian Liras? h 50009000 h10,000

14,000 h15,00019,000 h 20,00024,000 h 24,000 and over

4 Including the current year, how many years have you been teaching?

h 15 h 610 h 1115 h 1620 h over 20

5 In what type of school do you teach h Urban h Suburban h Rural

6 What is your highest completed academic degree?

h Teacher Certicate h Bachelors h Masters

7 Have you ever attended any training course, workshop, or seminar on using computers?

h No h Yes.

If Yes, please specify the number of hours and/or days: - - - -hours - - - -days

396

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

8 What is the teaching method you use most often?

h Active discussion

h Collaborative activities

h Demonstration

h Hands-on learning

h Lecturing

h Role playing

h Computer-assisted instruction

h Other (please specify):

References

Abas, Z. W. (1995a). Attitudes towards using computers among Malaysian teacher education students. In J. D. Tinsley,

& T. J. van Weert (Eds.), World conference on computers in education VI: WCCE 95 liberating the learner (pp.

153162). London: Chapman & Hall.

Abas, Z. W. (1995b). Implementation of computers in Malaysian schools: problems and successes. In D. Watson, & D.

Tinsley (Eds.), Integrating information technology into education (pp. 151158). London: Chapman & Hall.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Clis, NJ: PrenticeHall, Inc..

Al-Oteawi, S. M. (2002). The perceptions of Administrators and teachers in utilizing information technology in

instruction, administrative work, technology planning and sta development in Saudi Arabia. Doctoral dissertation,

Ohio University.

Bannon, S. H., Marshall, J. C., & Fluegal, S. (1985). Cognitive and aective computer attitude scales: a validation

study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 45(2), 681.

Baylor, A., & Ritchie, D. (2002). What factors facilitate teacher skill, teacher morale, and perceived student learning in

technology-using classrooms?. Computers & Education, 39(1), 395414.

Bear, G. G., Richards, H. C., & Lancaster, P. (1987). Attitudes toward computers: validation of a computer attitude

scale. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 3(2), 207218.

Becker, H. J. (1998). Running to catch a moving train. Theory into Practice, 37(1), 2030.

Benzie, D. (1995). IFIP Working group 3.5: using computers to support young learners. In J. D. Tinsley, & T. J. van

Weert (Eds.), World conference on computers in education VI: WCCE 95 liberating the learner (pp. 3542). London:

Chapman & Hall.

Berner, J. E. (2003). A study of factors that may inuence faculty in selected schools of education in the Commonwealth

of Virginia to adopt computers in the classroom. Doctoral Dissertation, George Mason University. ProQuest

Digital Dissertations (UMI No. AAT 3090718).

Blankenship, S. E. (1998). Factors related to computer use by teachers in classroom instruction. Doctoral Dissertation,

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Bulkeley, W. (1993). Computers failing as teaching aids. In T. Cannings, & L. Finkel (Eds.), The technology age

classroom (pp. 810). Wilsonville, OR: Franklin, Beedle & Associates, Inc..

Bullock, D. (2004). Moving from theory to practice: an examination of the factors that preservice teachers encounter as

they attempt to gain experience teaching with technology during eld placement experiences. Journal of Technology

and Teacher Education, 12(2), 211237.

Christensen, R. (1998). Eect of technology integration education on the attitudes of teachers and their students.

Doctoral dissertation, University of North Texas. Retrieved on 12 November, 2003, from http://www.tcet.unt.edulresearch/dissert/rhondac.

Christensen, R., & Knezek, G. (1996). Constructing the teachers attitudes toward computers (TAC) questionnaire.

ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED398244.

Clark, R. (1983). Reconsidering research on learning from media. Review of Educational Research, 53(4), 445459.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). Beverley

Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

397

Damarin, S. K. (1998). Technology and multicultural education: the question of convergence. Theory into Practice,

37(1), 1119.

Dillman, D. A. (1978). Mail and telephone surveys: The total design method. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Francis-Pelton, L. & Pelton, T. (1996). Building attitudes: how a technology course aects pre-service teachers attitudes

about technology. Retrieved on 16 April 2004 from: http://web.uvic.ca/educ/lfrancis/web/attitudesite.html.

Gardner, D. G., Discenza, R., & Dukes, R. L. (1993). The measurement of computer attitudes: an empirical

comparison of available scales. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 9(4), 487507.

Gay, L. R., & Airasian, P. (2000). Educational research: Competencies for analysis and application (6th ed.). New Jersey:

Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Gressard, C. P., & Loyd, B. H. (1986). Validation studies of a new computer attitude scale. Association for Educational

Data Systems Journal, 18, 295301.

Harper, D. O. (1987). The creation and development of educational computer technology. In R. M. Thomas, & V. N.

Kobayashi (Eds.), Educational technology its creation, development and cross-cultural transfer (pp. 3564). Oxford:

Pergamon Press.

Harrison, A. W., & Rainer, R. K. (1992). The inuence of individual dierences on skill in end-user computing. Journal

of Management Information Systems, 9(1), 93111.

Hodas, S. (1993). Technology refusal and the organizational culture of schools. Education Policy Analysis Archives,

1(10). Retrieved on 29 January, 2004 from http://epaa.asu.edu/epaa/v1n10.html.

Isleem, M. (2003). Relationships of selected factors and the level of computer use for instructional purposes by

technology education teachers in Ohio public schools: a statewide survey. Doctoral dissertation, the Ohio State

University.

Jones, T., & Clarke, V. A. (1994). A computer attitude scale for secondary students. Computers Education, 22(4),

315318.

Kersaint, G., Horton, B., Stohl, H., & Garofalo, J. (2003). Technology beliefs and practices of mathematics education

faculty. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 11(4), 549577.

Kluever, R. C., Lam, T. C., Homan, E. R., Green, K. E., & Swearinges, D. L. (1994). The computer attitude scale:

assessing changes in teachers attitudes toward computers. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 11(3),

251261.

Knezek, G., & Christensen, R. (2002). Impact of new information technologies on teachers and students. Education and

Information Technologies, 7(4), 369376.

Koohang, A. A. (1989). A study of the attitudes toward computers: anxiety, condence, liking, and perception of

usefulness. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 22(2), 137150.

Laord, P. A., & Laord, B. A. (1997). Learning language and culture with Internet technologies. In M. Bush, &

R. M. Terry (Eds.), Technology-enhanced language learning (pp. 215262). Lincolnwood, IL: National textbook

Company.

Li, N. (2002). Culture and gender aspects of students information searching behaviour using the Internet: a two-culture

study of China and the United Kingdom. Doctoral Dissertation, Open University United Kingdom. ProQuest

Digital Dissertations.

Meier, S. T. (1988). Predicting individual dierences in performance on computer-administered tests and tasks:

development of the computer aversion scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 4(1), 175187.

Na, S. I. (1993). Variables associated with attitudes of teachers toward computers in Korean vocational agriculture high

schools. Doctoral dissertation, The Ohio State University.

National Report of the Syrian Arab Republic on Education for All. (2000). Year 2000 Evaluation, Part I. EFA

FORUM, Education for All, UNESCO.

North Central Regional Educational Laboratory (NCREL). (2003). Technology connections for school improvement:

planners handbook. Retrieved on 16 April 2004 from http://www.ncrel.org/tplan/tplanB.htm.

Ojo, S., & Awuah, B. (1998). Building resource capacity for IT education and training in schools the case of

Botswana. In G. Marshall, & M. Ruohonen (Eds.), Capacity building for IT in education in developing countries (pp.

2738). London: Chapman & Hall.

Pelgrum, W. J. (2001). Obstacles to the integration of ICT in education: results from a worldwide educational

assessment. Computers & Education, 37(2001), 163178.

398

A. Albirini / Computers & Education 47 (2006) 373398

Robertson, S., Calder, J., Fung, P., Jones, A., & OShea, T. (1995). Computer attitudes in an English secondary school.

Computers & Education, 24, 7381.

Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diusion of innovations (4th ed.). New York: The Free Press.

Rogers, E. M., & Shoemaker, F. F. (1971). Communication of innovations. New York: Free Press.

Salaberry, R. (2001). The use of technology for second language learning and teaching: a retrospective. The Modern

Language Journal, 85(1), 3956.

Salamon, D. (2002). Technology and pedagogy: why dont we see the promised revolution?. Educational technology,

42(1), 7175.

Selwyn, N. (1997). Students attitudes toward computers: validation of a computer attitude scale for 1619 education.

Computers & Education, 28(1), 3541.

Sooknanan, P. (2002). Attitudes and perceptions of teachers toward computers: the implication of an educational

innovation in Trinidad and Tobago. Doctoral dissertation, Bowling Green University.

Summers, M. (1990). New student teachers and computers: an investigation of experiences and feelings. Educational

Review, 42(3), 261271.

Swadener, M., & Hannan, M. (1987). Gender similarities and dierences in sixth graders attitudes toward computers:

an exploratory study. Educational Technology, 27(1), 3742.

Thomas, R. M. (1987). Computer technology: an example of decision-making in technology transfer. In R. M. Thomas,

& V. N. Kobayashi (Eds.), Educational echnology its creation, development and cross-cultural transfer (pp. 2534).

Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Thompson, A. D., Simonson, M. R., & Hargrave, C. P. (1992). Educational technology: A review of the research.

Washington, DC: Association for Educational Communication and Technology.

Watson, D. M. (1998). Blame the technocentric artifact! What research tells us about problems inhibiting teacher use of

IT. In G. Marshall, & M. Ruohonen (Eds.), Capacity building for IT in education in developing countries (pp.

185192). London: Chapman & Hall.

Woodrow, J. E. (1992). The inuence of programming training on the computer literacy and attitudes of pre-service

teachers. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 25(2), 200219.

Young, E. B. (1991). Empowering teachers to use technology in their classrooms. Computers in the Schools, 8, 143147.

Zimbardo, P., Ebbesen, E., & Maslach, C. (1977). Inuencing attitudes and changing behavior. Reading, MA: AddisonWesley Publishing Company.

You might also like

- ADJECTIVES1describing People PDFDocument3 pagesADJECTIVES1describing People PDFranju1978No ratings yet

- Fun Quartet Game Revises Character AdjectivesDocument2 pagesFun Quartet Game Revises Character Adjectivesranju1978No ratings yet

- Adjectives Characters FlashcardsDocument3 pagesAdjectives Characters Flashcardsranju1978No ratings yet

- How Many Dancers Are Under The Dragon?Document1 pageHow Many Dancers Are Under The Dragon?ranju1978No ratings yet

- Adjectives WorksheetDocument2 pagesAdjectives Worksheetranju1978No ratings yet

- Phonics Ue & AwDocument6 pagesPhonics Ue & Awranju1978No ratings yet

- Speaking Activity For BeginnerDocument1 pageSpeaking Activity For Beginnerranju1978No ratings yet

- Practice Unit 7Document2 pagesPractice Unit 7ranju1978No ratings yet

- English Language WorksheetDocument9 pagesEnglish Language Worksheetranju1978No ratings yet

- Adjectives FlashcardsDocument4 pagesAdjectives Flashcardsranju1978No ratings yet

- Puzzle ShapeDocument1 pagePuzzle Shaperanju1978No ratings yet

- Phisical AppearanceDocument27 pagesPhisical AppearanceLuis QuanNo ratings yet

- Ucapan World Thinking DayDocument2 pagesUcapan World Thinking Dayranju1978No ratings yet

- Kemahiran Abad 21Document22 pagesKemahiran Abad 21lohchoonpengNo ratings yet

- Ucapan World Thinking DayDocument2 pagesUcapan World Thinking Dayranju1978No ratings yet

- Days of The WeekDocument27 pagesDays of The Weekranju1978No ratings yet

- Raining Cat and Dogs PDFDocument1 pageRaining Cat and Dogs PDFranju1978No ratings yet

- English The Days of The WeekDocument27 pagesEnglish The Days of The Weekranju1978No ratings yet

- PostersDocument48 pagesPostersranju1978No ratings yet

- Rules of The SchoolDocument31 pagesRules of The Schoolranju1978100% (2)

- RulesDocument3 pagesRulesranju1978No ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension - Lower LevelDocument20 pagesReading Comprehension - Lower Levelranju1978No ratings yet

- Equality of Education PDFDocument14 pagesEquality of Education PDFranju1978No ratings yet

- Primary Curriculum Framework 2018 PDFDocument44 pagesPrimary Curriculum Framework 2018 PDFYanie JamalNo ratings yet

- Rules of The SchoolDocument31 pagesRules of The Schoolranju1978No ratings yet

- Posternumberswords1 20Document1 pagePosternumberswords1 20Arijana JusufovicNo ratings yet

- Ucapan World Thinking DayDocument2 pagesUcapan World Thinking Dayranju1978No ratings yet

- Yearlyschemeofwork Year5 2015Document13 pagesYearlyschemeofwork Year5 2015ranju1978No ratings yet

- Wfun15 Cut Paste Beginning Sound 2Document1 pageWfun15 Cut Paste Beginning Sound 2ranju1978No ratings yet

- Wfun15 Cut Paste Beginning Sound 1Document1 pageWfun15 Cut Paste Beginning Sound 1ranju1978No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- An Introduction To Pascal Programming MOD 2010Document5 pagesAn Introduction To Pascal Programming MOD 2010Johnas DalusongNo ratings yet

- Catering Reserving and Ordering System with MongoDB, Express, Node.js (39Document5 pagesCatering Reserving and Ordering System with MongoDB, Express, Node.js (39radha krishnaNo ratings yet

- Veiga Et Al. 2015 - Composition, Structure and Floristic Diversity in Dense Rain Forest inDocument8 pagesVeiga Et Al. 2015 - Composition, Structure and Floristic Diversity in Dense Rain Forest inYakov Mario QuinterosNo ratings yet

- Carl Rogers, Otto Rank, and "The BeyondDocument58 pagesCarl Rogers, Otto Rank, and "The BeyondAnca ElenaNo ratings yet

- Đề Minh Họa 2020 Số 23 - GV Trang Anh - Moon.vnDocument22 pagesĐề Minh Họa 2020 Số 23 - GV Trang Anh - Moon.vnLily LeeNo ratings yet

- Calmark - Birtcher 44 5 10 LF L DatasheetDocument2 pagesCalmark - Birtcher 44 5 10 LF L DatasheetirinaNo ratings yet

- Frame Fit Specs SramDocument22 pagesFrame Fit Specs SramJanekNo ratings yet

- Innovations in Drill Stem Safety Valve TechnologyDocument22 pagesInnovations in Drill Stem Safety Valve Technologymiguel mendoza0% (1)

- GulliverDocument8 pagesGulliverCris LuNo ratings yet

- OSC - 2015 - Revised - Oct (Power Cables) PDFDocument118 pagesOSC - 2015 - Revised - Oct (Power Cables) PDFIván P. MorenoNo ratings yet

- Statistics Interview QuestionsDocument5 pagesStatistics Interview QuestionsARCHANA R100% (1)

- Presentation SkillsDocument22 pagesPresentation SkillsUmang WarudkarNo ratings yet

- Kompres Panas Dingin Dapat Mengurangi Nyeri Kala I Persalinan Di Rumah Sakit Pertamina Bintang AminDocument9 pagesKompres Panas Dingin Dapat Mengurangi Nyeri Kala I Persalinan Di Rumah Sakit Pertamina Bintang AminHendrayana RamdanNo ratings yet

- INJSO Answer Key & SolutionDocument5 pagesINJSO Answer Key & SolutionYatish Goyal100% (1)

- Journal of Travel & Tourism MarketingDocument19 pagesJournal of Travel & Tourism MarketingSilky GaurNo ratings yet

- BOQ Sample of Electrical DesignDocument2 pagesBOQ Sample of Electrical DesignAshik Rahman RifatNo ratings yet

- Assembly Transmission Volvo A40GDocument52 pagesAssembly Transmission Volvo A40GNanang SetiawanNo ratings yet

- 2. Green finance and sustainable development in EuropeDocument15 pages2. Green finance and sustainable development in Europengocanhhlee.11No ratings yet

- Chalk & TalkDocument6 pagesChalk & TalkmathspvNo ratings yet