Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Emotional Intelligence and Resilience

Uploaded by

Bogdan HadaragCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Emotional Intelligence and Resilience

Uploaded by

Bogdan HadaragCopyright:

Available Formats

Personality and Individual Differences 55 (2013) 909914

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Personality and Individual Differences

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/paid

Emotional intelligence and resilience

Tamera R. Schneider a,, Joseph B. Lyons b, Steven Khazon a

a

b

Wright State University, 3640 Col. Glenn Hwy., Dayton, OH 45435, United States

Air Force Research Laboratory, 875 N. Randolph St., Arlington, VA, United States

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 30 January 2013

Received in revised form 10 July 2013

Accepted 15 July 2013

Available online 6 August 2013

Keywords:

Emotional intelligence

Appraisal

Affect

Physiology

Positive psychology

a b s t r a c t

This study examined the relationship between emotional intelligence (EI) and the stress process. Participants (N = 126) completed an ability-based measure of EI and then engaged with two stressors. We

assessed stressor appraisals, emotions, and physiological stress responses over time. We expected that

higher EI would facilitate stress responses in the direction of challenge, rather than threat. As expected,

EI facets were related to lower threat appraisals, more modest declines in positive affect, less negative

affect and challenge physiological responses to stress. However, ndings differed for men and women.

This study provides predictive validity that EI facilitates stress resilience.

2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Emotional intelligence and resilience

Emotional intelligence (EI), ones ability to perceive, integrate,

understand, and manage emotions, has received a great deal of

attention (Zeidner, Roberts, & Matthews, 2004). Popular literature

promises benets of EI (Goleman, 1995), but these have not been

established (Landy, 2005; Zeidner et al., 2004). Debates over conceptualization and measurement have delayed research (Davies,

Stankov, & Roberts, 1998; Matthews, Zeidner, & Roberts, 2007).

Mixed (trait) models describe EI as skills, personality, and wellbeing (Bar-On, 1997; Goleman, 1995), whereas ability-based models describe EI as an intelligence comprising emotional abilities

(Mayer, Caruso, & Salovey, 1999, 2000). To be labeled intelligence

a construct must be dened as a set of abilities, related to other

measures of cognitive ability, and develop with age (Carroll,

1993). Trait-based conceptualizations do not meet these criteria

(e.g., Roberts, MacCann, Matthews, & Zeidner, 2010; Schulze, Wilhelm, & Kyllonen, 2007), but ability-based conceptualizations do

(Austin, 2010; Mayer, Caruso, & Salovey, 1999). The MSCEIT is

the most validated ability measure (Matthews et al., 2007; Roberts

et al., 2010), and its four-factor framework stems from theory (e.g.,

MacCann & Roberts, 2008). We examined the inuence of abilitybased EI on stress responses appraisals, emotions, and physiology

as the stress process unfolds over time.

Corresponding author. Address: Wright State University, Department of

Psychology, 335 Fawcett, Dayton, OH 45435, United States. Tel.: +1 (937) 775

2391; fax: +1 (937) 775 3347.

E-mail address: tamera.schneider@wright.edu (T.R. Schneider).

0191-8869/$ - see front matter 2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.07.460

Emotional intelligence comprises a set of four emotional skills

including accurately perceiving emotions, integrating emotions

with cognition, understanding emotional causes and consequences, and managing emotions for personal adjustment (Mayer

& Salovey, 1997; Salovey, Bedell, Detweiler, & Mayer, 1999; Salovey, Kokkonen, Lopes, & Mayer, 2004). These skills build hierarchically, from the ability to perceive emotions up to managing

emotions. Perceiving emotions includes the ability to accurately

identify and express emotions, which helps to discriminate between hospitable and hostile situations. The ability to generate

and use emotions to enhance thinking includes altering emotion

to redirect cognitive processes, obtain new perspectives, and enhance problem-solving or creativity. Emotional understanding includes the ability to understand emotional information, the

manner in which they combine, and their causes and consequences. Emotional management includes the ability to be open

to feelings and modulate them to facilitate growth, even during

duress. People experiencing specic and intense emotional

changes should benet from EI (Barrett, Gross, Christensen, & Benvenuto, 2001), however research on EI and stress outcomes is

lacking.

The stress process begins with evaluations, or appraisals, denoting our interpretation of an impending stressful situation (Lazarus,

1999; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Primary appraisals are evaluations about the personal relevance of the situation whether it

threatens goals, resources, or values. Secondary appraisals are beliefs about potential resources available for meeting stressor demands. Given an impending stressor, primary and secondary

appraisals interact, resulting in a continuum ranging from challenge to threat. Challenge occurs when adequate resources are

910

T.R. Schneider et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 55 (2013) 909914

deemed to meet situational demands, whereas threat results when

situational demands outweigh resources (Lazarus & Folkman,

1984). Challenge and threat appraisals are differently related to

physiological responses, performance (Schneider, 2004; Tomaka,

Blascovich, Kelsey, & Leitten, 1993), and emotions (Schneider,

2004, 2008). Physiologically, both threatened and challenged

groups are mobilized with increased heart rate (HR) and some increase in cardiac output (CO; the amount of blood pumped out of

the heart over time), however the pattern of blood ow differs

(Schneider, 2004, 2008). Challenge appraisals evoke increases in

cardiac reactivity (increased HR and CO) coupled with peripheral

vasodilation (vasculature is more accepting of blood ow) (Schneider, 2004, 2008; Tomaka et al., 1993). Threatened participants have

a smaller increase in cardiac reactivity coupled with enhanced

vasoconstriction (vasculature is less accepting of blood ow). Challenged participants outperform threatened participants on motivated performance, active coping tasks (Schneider, 2004; Tomaka

et al., 1993), and on complex skills training and transfer (Gildea,

Schneider, & Shebilske, 2007). Challenged participants also experience more positive affect and less negative affect than threatened

participants (Schneider, 2004, 2008). Most psychophysiological

stress research focuses on a single stressor, but we investigated

the role of ability-based EI on stress responses over time.

People appraise situations differently, with some more vulnerable to negative stress outcomes (Basic Behavioral Science Task

Force of the National Advisory Mental Health Council Basic Behavioral Science Task Force of the National Advisory Mental Health

Council Basic Behavioral Science Task Force of the National Advisory Mental Health Council Basic Behavioral Science Task Force

of the National Advisory Mental Health Council Basic Behavioral

Science Task Force of the National Advisory Mental Health Council

BBSTFNAMHC, 1996; Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996; Schneider, 2004;

Vollrath & Torgersen, 2000). Appraisals should be inuenced by

dispositions (Lazarus, 1999; Lyons & Schneider, 2005; Schneider

2004). Past research has found that high assertiveness predicts

challenge appraisals of a speech stressor (Tomaka et al., 1993),

and higher just world beliefs (beliefs that the world is just and fair)

predict challenge appraisals of a math stressor (Tomaka & Blascovich, 1994). Although EI has clear implications for emotional responses, it has yet to be examined with these robust stress

outcomes. Emotions play a fundamental role in shaping our reactions to external stimuli and help to focus our attention, aid in

interpreting harms or benets, and motivate us to respond to

anticipated or actual events that are personally relevant (Salovey

et al., 2004; Zajonc, 1998).

Emotional intelligence should confer benets during duress

(Brackett, Palomera, Mojsa-Kaja, Reyes, & Salovey, 2010; Ciarrochi,

Deane, & Anderson, 2002; Matthews & Zeidner, 2000; Nikolaou &

Tsaousis, 2002; Ramos, Fernandez-Berrocal, & Extremera, 2007;

Salovey et al., 1999; Stroud, Salovey, Woolery, & Epel, 2002). Most

EI-stress research has focused on self-reported, trait EI. It has been

linked to actively coping with stressors (Stroud et al., 2002), lower

subjective work stress (Nikolaou & Tsaousis, 2002), and a benecial

moderator of the link between stress and health (EP and EM; Ciarrochi et al., 2002). These studies suggest that EI may foster resilience, although self-reported EI lacks validity (Davies et al., 1998;

Schulze et al., 2007). Examining ability EI, Brackett et al. (2010)

found that emotional regulation predicts burnout and job satisfaction in secondary school teachers. Research examining ability EI

and stress responses is lacking (Salovey et al., 2004). Furthermore,

females outperform males on ability EI measures (Day & Carroll,

2004; Kafetsios, 2004; Lyons & Schneider, 2005). Little is known

about the inuence of ability EI on stress responses, and for men

and women separately.

We examined the role of ability EI on psychophysiological stress

responses. We posited that EI should promote resilient and

adaptive functioning during stressful situations for men and women. Given the paucity of research we did not offer predictions

for specic facets or different genders. Instead, we expected that

men and women who score higher in EI would appraise an

impending stressor as a challenge, experience more positive and

less negative affect, and exhibit challenge physiology (greater cardiac reactivity coupled with vasodilation), compared to those lower in EI who were expected to appraise the stressors with greater

threat, less positive and more negative affect, and threat physiology (modest increase in cardiac reactivity coupled with vasoconstriction). This hypothesis was examined by branch, for men and

women separately because of gender differences in EI (Day & Carroll, 2004; Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2000) and the primary goal of

this research was to investigate EI and stress resilience, not control

for EI to examine gender differences in stress responses.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Undergraduate psychology students (N = 126) attending a midwestern university participated in exchange for course credit. The

average age was 20 (SD = 4.6). Most were female (60%), freshman

(67%), and Caucasian (70%).

2.2. Stress manipulations

We used two motivated performances, active coping stressors,

where people actively construct responses rather than sit passively

and endure some stimulus (e.g., cold pressor, slide viewing). Both

commonly used tasks are validated psychophysiological stressors

(Kelsey et al., 2000, 1999; Saab, Matthews, Stoney, & McDonald,

1989). The rationale for the use of two stressors was to counteract

psychophysiological habituation responses (Kelsey et al., 1999).

2.2.1. Mental arithmetic task

For three minutes participants were to count backward from a

four-digit number by sevens, aloud, as quickly and accurately as

possible. They were told their responses would be evaluated.

2.2.2. Speech task

In the role of middle manager, participants delivered a videotaped speech (1 min preparation, 2 min delivery) in which they defended themselves against an employees sexual harassment

accusation.

2.3. Materials

2.3.1. Emotional intelligence

The MSCEIT V2.0 is a 141-item, ability-based measure with four

subscales (Mayer et al., 2000). Emotional perception has participants identify emotions in faces and pictures. Facilitating cognition

has participants compare emotions to sensations and discern the

usefulness of emotions in different situations. Emotional understanding has participants reduce numerous emotions down to

one and identify the result of conicting emotions. Emotional management has participants discern the emotions of different characters in stories. Test manual as are .91, .90, .77, and .87,

respectively. The publisher provided branch scores.

2.3.2. Stress appraisals

Two-items assessed appraisals: How threatening do you expect the upcoming task to be (primary)? and How able are you

to handle the burden of the task (secondary)? These were

911

T.R. Schneider et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 55 (2013) 909914

combined in a ratio (primary/secondary) where higher scores denote threat (Schneider, 2004).

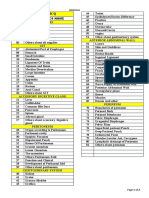

Table 2

Means (SD) for mens appraisals and affect over time, by EI branch (measured at

baseline).

Baseline

2.3.3. Positive and negative affect

The PANAS assessed positive and negative affect (Watson, Clark,

& Tellegen, 1988). Participants rated their experience of emotions,

at that moment, at baseline and after both tasks. Ten items assessed positive affect (e.g., attentive, excited, inspired; as = .83,

.87, and .91, respectively), and ten assessed negative affect (e.g.,

distressed, hostile, afraid; as = .83, .79, and .84, respectively).

2.3.4. Physiological measures

An impedance cardiograph and continuous blood pressure

monitor provided data to derive cardiac output and total peripheral resistance. Data collection was in accordance with published

standards (Sherwood et al., 1990). Data were reduced ofine with

interactive software. Baseline equivalence of groups was

established.

2.4. Procedure

After obtaining consent, participants completed the MSCEIT online. They were seated in a sound-dampened chamber and physiological sensors were attached, followed by a 10-min physiological

baseline. A baseline PANAS was completed. Random assignment

to task was followed by task instruction. After instruction, appraisals were assessed, the task commenced, and state affect was

assessed. A 2-min recovery separated tasks. Then, task 2 instructions were given, and the sequence repeated. Sensors were

detached and participants debriefed.

3. Results

This study examined stress reactions (appraisals, affect, physiology) over time. Repeated measures ANOVAs were used to test

the hypotheses pertaining to appraisals and affect. Physiological

data were analyzed using a MANOVA. The task order was counterbalanced (math rst or speech rst) and this served as an independent variable in preliminary analysis. With the exception of

descriptive analyses using gender as an IV (see Table 1), analyses

examining the inuence of EI on stress responses were conducted

for men and women separately (using two gender datasets). Lastly,

to maximize power, EI branches were examined as covariates

Appraisals

Low emotional management

High emotional management

Time 1

Time 2

.74 (.50)

.72 (.42)

.94 (.83)

.65 (.34)

Positive affect

Low emotional understanding

High emotional understanding

2.50 (.69)

3.00 (.68)

2.20 (.65)

2.86 (.80)

1.96 (.75)

2.63 (.88)

Negative affect

Low emotional perception

High emotional perception

1.77 (.63)

1.29 (.34)

1.96 (.75)

1.51 (.44)

2.02 (.76)

1.45 (.40)

rather than dichotomized (MacCallum, Zhang, Preacher, & Rucker,

2002). In summary, repeated-measures ANCOVAs or the MANCOVA were conducted with emotional perception (EP), facilitating

cognition (FC), emotional understanding (EU), and emotional management (EM) as covariates and stress reactions (appraisals, affective responses, and physiology) over time as dependent variables,

for men and for women separately.

First, preliminary analyses investigated order effects, using repeated-measures M/ANOVAs with order (math rst or speech rst)

as the independent variable and stress responses as dependent

variables, for each gender. As expected, responses to the stressors

were equivalent, order had no effect on appraisals, emotions, or

physiology for men or women, ns. Subsequent analyses are collapsed across order. Descriptive ndings are in Table 1. Women

scored higher on EI branches than men, signicantly so for EM,

as in past research (Lopes, Salovey, Cote, & Beers, 2005). Thus, we

conducted analyses for men and women separately. Table 1 also

shows that relative to men, women reported signicantly more

threat before and less positive affect after the rst task, more negative affect after both tasks, and had lower cardiac output at

baseline.

Four (EI branch) repeated-measures ANCOVAs were conducted

with EI branch as the covariate and appraisals as the repeated

DV (time 1 and 2), for men and women separately. For both datasets (men, women), there were no main effects of time, or branch

with time interactions, ns. EM had a signicant covariate effect on

appraisals, but only for men. Table 2 shows that men higher in EM

were more challenged than those lower in EM, F(1, 49) = 4.78,

Table 1

Means (SD) for EI facets, appraisals, affect, and physiology, for men and women separately.

Emotional perception

Facilitating cognition

Emotional understanding

Emotional management

Appraisals: time 1

Appraisals: time 2

Positive affect: baseline

Positive affect: time 1

Positive affect: time 2

Negative affect: baseline

Negative affect: time 1

Negative affect: time 2

Cardiac output: baseline

Cardiac output: time 1

Cardiac output: time 2

TPR: baseline

TPR: time 1

TPR: time 2

Overall mean

Females (n = 75)

Males (n = 51)

98.45 (15.46)

95.26 (15.00)

89.32 (8.71)

90.62 (10.37)

.94 (.58)

1.01 (.83)

2.57 (.71)

2.31 (.76)

2.12 (.87)

1.58 (.52)

1.95 (.69)

1.97 (.78)

42.49 (11.74)

47.47 (16.30)

46.81 (16.71)

158.97 (54.54)

146.11 (87.82)

147.73 (86.28)

100.23 (14.80)

97.20 (14.42)

90.47 (8.85)

92.59 (10.04)a

1.09 (.60)a

1.12 (.89)

2.47 (.69)

2.19 (.72)a

2.03 (.88)

1.58 (.49)

2.07 (.68)a

2.10 (.80)a

39.99 (8.96)a

45.27 (11.01)

47.20 (11.69)

161.02 (48.42)

146.84 (70.50)

136.20 (56.31)

95.83 (16.16)

92.41 (15.52)

87.63 (8.30)

87.73 (10.27)b

.73 (.48)b

.86 (.73)

2.71 (.72)

2.47 (.78)b

2.24 (.86)

1.58 (.58)

1.78 (.68)b

1.80 (.72)b

46.11 (14.28)b

52.06 (19.65)

47.72 (20.68)

156.27 (62.45)

149.65 (106.78)

168.56 (112.46)

Note. Different superscripts denote signicant differences, p < .05. TPR = Total Peripheral Resistance. Cardiac output and TPR means are from 77 participants (45 females, 32

males).

912

T.R. Schneider et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 55 (2013) 909914

60

4. Discussion

CO (liters/min)

50

High EM

Low EM

40

30

20

Baseline

Time 1

Time 2

200

b

5

TPR (dyne-sec/cm^ )

180

160

High EM

Low EM

140

120

100

Baseline

Time 1

Time 2

Fig. 1. Mean cardiac output (a) and Total Peripheral Resistance (b) over time for

females high or low in emotional management.

p < .05. No EI branches were signicantly related to appraisals for

women.

Four repeated-measures ANCOVAs were conducted with branch

as the covariate, and affective responses as the DV over time (baseline, time 1, time 2), for men and women datasets. Positive and

negative affect are separate dependent variables because they are

orthogonal (Watson et al., 1988). For each DV and dataset, there

were no main effects of time, or branch with time interactions,

ns. Table 2 shows that relative to their low EI counterparts, men

higher in EU reported more positive affect, F(1, 49) = 5.51, p < .05,

and men higher in EP reported less negative affect, F(1,

49) = 5.31, p < .05.

Four repeated-measures MANCOVAs were conducted with EI

covaried, and CO and TRP as the DV over time (baseline, time 1,

time 2), for each dataset. CO and TPR are interdependent physiological responses dictating MANOVA. For each dataset there were

no effects of time, or branch with time interactions, ns. For women

there was a signicant multivariate main effect for EM, Wilks F(2,

38) = 9.02, p < .001. Figure 1a and b shows that relative to those

lower in EM, women higher in EM had challenge physiology: greater CO, F(1, 39) = 12.99, p < .001, coupled with decreased TPR, F(1,

39) = 18.52, p < .0011.

1

Figure 1a displays inated values for cardiac output. Cardiac output is derived

from heart rate and stroke volume. Heart rate values were appropriate, but stroke

volume values were inated. Stroke volume is inuenced by several factors, and

largely by changes in the position of the person (e.g., supine versus seated). Because

all participants were seated for the duration of the experiment, these inated values

are likely consistent across participants.

We expected that the four EI abilities would facilitate resilient

stress responses including challenge appraisals, more positive

and less negative affect, and challenge physiology for men and women. We found that the inuence of EI on stress responses is not

ubiquitous, but generally that EI conferred stress resilience. We

discuss each EI branch in turn.

Emotional perception (EP) facilitated signicantly lower negative affect for men across the course of stressor exposures. Using

a cross-sectional design, EP has been related to self-reported

depression, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation (Ciarrochi et al.,

2002), suggesting that EP enhances negative affectivity during

stress. However, our research shows that men with EP ability have

reduced negative affective stress responses over time. We demonstrated that negative affect remains low during stressful transactions for those higher in EP. Perhaps the ability to recognize

emotional responses brought on by an external stressor evokes a

correction in reports of emotional experience that is sustained over

time.

The facilitating cognition (FC) facet was not related to stress responses in the present study. Negative emotions narrow attention

(Craske, 1999), but positive emotions evoke openness and creativity (Isen, Daubman, & Nowicki, 1987). The stressors in this study

were motivated performance tasks with an evaluative component

that may have made them unrelated to FC. Performance metrics

(not obtained in this study) are differently related to stressor

appraisals (Schneider, 2004, 2008; Tomaka et al., 1993), and may

have been related to FC a query for future research.

Emotional understanding (EU) facilitated resilience. Higher EU

in men was associated with more positive affect across the stressors than lower EU. EU should allow for rened identication of and

precise attributions about emotional experiences. Although we

introduced salient causes for emotional change, the higher positive

affect of men higher in EU was sustained over time. These men noticed and reported higher positive affect, and may have attributed

affective changes to the transient stressors. Maintaining mood may

be an active affect control process (Forgas & Ciarrochi, 2002).

Whether EU confers a mood maintenance effect, or reduces the effort to maintain affect is a question for future research.

We expected that higher EI ability would evoke challenge

appraisals. Men higher in EM reported challenge relative to their

low EM counterparts. High EM men had benign stressor appraisals

that remained, whereas low EM men were more threatened that

was sustained. EM is the highest EI ability (Salovey et al., 1999)

and should inuence the integration of responses for situations

involving social interactions (Lopes et al., 2005) and stress adaptation. Examining more than two stressors may have revealed significant effects on appraisals over time. Appraisals set the stress

process in motion (Schneider, 2004; Tomaka et al., 1993) and are

most open to modication. Further investigation could point to

ways in which high EM builds or low EM reduces resilience, suggested by the pattern of appraisals obtained in the present study.

Despite women having higher EM ability than men, they did not

benet from reduced stressor or benecial emotional reactions.

Descriptive analyses (Table 1) revealed that after the rst task

exposure, women were more threatened than men, and reported

lower positive affect initially and higher negative affect across both

tasks, than men. Past research shows that threat appraisals predict

lower positive and higher negative affect (Schneider, 2004). Despite experiencing the stressor more intensely (in terms of appraisals and affect), women higher in EM did experience greater

physiological challenge. It may be that their higher EM ability facilitated a more salubrious physiological response (greater CO coupled with decreased TRP), a physiological challenge response

T.R. Schneider et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 55 (2013) 909914

(Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996; Schneider, 2004, 2008; Tomaka et al.,

1993). More differentiated and intense negative affectivity is related to greater emotion regulation efforts (Barrett et al., 2001),

which may have been supported by an active coping physiology

in high EM women. In the present study, men appeared to have

greater variability in vascular resistance which may have precluded our establishing meaningful relationships.

Although our descriptive analyses suggested that women were

more negatively affected by the stressor than men, this did not result in more associations of EI and stress responses for women. The

women in this study were neither homogenous in EI levels, nor restricted in their range of stress responses. However, the type of

stressors used in the present research may be part of the issue. Social stressors evoke greater reactivity among women compared to

men (Stroud et al., 2002). Although women evidenced stress responses to the tasks in the present research, perhaps more socially-oriented stressors, such as a speed-dating type task, would

facilitate their ability to apply EI skills.

Another possible limitation of this study is that we did not control for the inuence of cognitive ability. Researchers have found

that intelligence is related to ability-based EI (e.g., Austin, 2010).

People with high cognitive ability may be better able to cope with

our stressors, thus our ndings might be partly attributed to cognitive ability rather than EI.2 This possibility is mitigated somewhat

by the modest relationship between EI and cognitive ability, but

should be explored in future research.

5.1. Implications

This is among the rst studies to expand on past research by

demonstrating ability-based EI facilitates stress resilience. We

used an ability EI measure rather than self-report, which lacks

validity (Davies et al., 1998), and we examined stress outcomes

over time. Interestingly, we found no interactions of EI branches

and time. The resilience effects of EI appear at stressor onset and

remain over time an area calling for future research. This study

examined women and men, separately because ability (Day & Carroll, 2004; Kafetsios, 2004) and self-report EI (Van Rooy, Alonso, &

Viswesvaran, 2004) consistently nd gender differences. Future research should consider how EI facets may be utilized differently by

men and women in different stressor contexts, and on adapting to

stress at work.

This study demonstrated that aspects of EI confer benets during the stress process by promoting resilient psychological and

physiological responses. The results provide some validation of EI

theory. The facets differently buffer stress responses by promoting

approach-oriented stressor appraisals, emotional experiences, and

physiological engagement. There has been popular speculation

about the promise of EI, and this research demonstrates stress-related benets of ability EI for men and women. We are optimistic

about the future of EI as the questions become more precise and

the ndings more valid.

References

Austin, E. J. (2010). Measurement of ability emotional intelligence: Results for two

new tests. British Journal of Psychology, 101, 563578.

Bar-On, R. (1997). The Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i): A test of emotional

intelligence. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems, Inc..

Barrett, L., Gross, J., Christensen, T., & Benvenuto, M. (2001). Knowing what youre

feeling and knowing what to do about it: Mapping the relation between

emotion differentiation and emotion regulation. Cognition and Emotion, 15,

713724.

Basic Behavioral Science Task Force of the National Advisory Mental Health Council

BBSTFNAMHC (1996). Basic behavioral science research for mental health:

Vulnerability and resilience. American Psychologist, 51, 2228.

2

We thank an anonymous reviewer for this comment.

913

Blascovich, J., & Tomaka, J. (1996). The biopsychosocial model of arousal regulation.

Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 28, 151.

Brackett, M. A., Palomera, R., Mojsa-Kaja, J., Reyes, M., & Salovey, P. (2010). Emotionregulation ability, burnout, and job satisfaction among British secondary-school

teachers. Psychology in the Schools, 47, 406417.

Carroll, J. B. (1993). Human cognitive abilities: A survey of factor analytic studies.

Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Ciarrochi, J., Deane, F., & Anderson, S. (2002). Emotional intelligence moderates the

relationship between stress and mental health. Personality and Individual

Differences, 32, 197209.

Craske, M. G. (1999). Anxiety disorders: Psychological approaches to theory and

treatment. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Davies, M., Stankov, L., & Roberts, R. D. (1998). Emotional intelligence: In search of

an elusive construct. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(4),

9891015.

Day, A. L., & Carroll, S. A. (2004). Using an ability-based measure of emotional

intelligence to predict individual performance, group performance, and group

citizenship behaviours. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 14431458.

Forgas, J. P., & Ciarrochi, J. V. (2002). On managing moods: Evidence for the role of

homeostatic cognitive strategies in affect regulation. Personality and Social

Psychology Bulletin, 28(3), 336345.

Gildea, K. M., Schneider, T. R., & Shebilske, W. L. (2007). Stress appraisals and

training performance on a complex laboratory task. Human Factors, 49(4),

745758.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. New York, NY England: Bantam Books,

Inc..

Isen, A. M., Daubman, K. A., & Nowicki, G. P. (1987). Positive affect facilitates

creative problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52,

11221131.

Kafetsios, K. (2004). Attachment and emotional intelligence abilities across the life

course. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 129145.

Kelsey, R. M., Blascovich, J., Leitten, C. L., Schneider, T. R., Tomaka, J., & Wiens, S.

(2000). Cardiovascular reactivity and adaptation to recurrent psychological

stress: Moderating effects of evaluative observation. Psychophysiology, 37,

748756.

Kelsey, R. M., Blascovich, J., Tomaka, J., Leitten, C. L., Schneider, T. R., & Wiens, S.

(1999). Cardiovascular reactivity and adaptation to recurrent psychological

stress: Effects of prior task exposure. Psychophysiology, 36, 818831.

Landy, F. J. (2005). Some historical and scientic issues related to research on

emotional intelligence. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 411424.

Lazarus, R. (1999). Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. New York: Springer

Publishing.

Lazarus, R., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer

Publishing.

Lopes, P. N., Salovey, P., Cote, S., & Beers, M. (2005). Emotional regulation abilities

and the quality of social interaction. Emotion, 5, 113118.

Lyons, J. B., & Schneider, T. R. (2005). The inuence of emotional intelligence on

performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 693703.

MacCallum, R. C., Zhang, S., Preacher, K. J., & Rucker, D. D. (2002). On the practice of

dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychological Methods, 7, 1940.

MacCann, C., & Roberts, R. D. (2008). New paradigms for assessing emotional

intelligence: Theory and data. Emotion, 8(4), 540551.

Matthews, G., & Zeidner, M. (2000). Emotional intelligence, adaptation to stressful

encounters, and health outcomes. In R. Bar-On & J. Parker (Eds.), The handbook of

emotional intelligence: Theory, development, assessment and application at home,

school, and in the workplace (pp. 459489). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/

Pfeiffer.

Matthews, G., Zeidner, M., & Roberts, R. D. (2007). Emotional intelligence:

Consensus, controversies, and questions. In G. Matthews, M. Zeidner, & R. D.

Roberts (Eds.), The science of emotional intelligence: Knowns and unknowns

(pp. 346). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press.

Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., & Salovey, P. (1999). Emotional intelligence meets

traditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence, 27(4), 267298.

Mayer, J., Caruso, D., & Salovey, P. (2000). Selecting a measure of emotional

intelligence: The case for ability scales. In R. Bar-On & J. Parker (Eds.), The

handbook of emotional intelligence: Theory, development, assessment and

application at home, school, and in the workplace (pp. 320342). San Francisco,

CA: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer.

Mayer, J., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. (2000). Manual for the MSCEIT (MayerSalovey

Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test). Toronto, Canada: MHS Publishers.

Mayer, J., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D.

Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational

implications (pp. 331). New York: Basic Books.

Nikolaou, I., & Tsaousis, I. (2002). Emotional intelligence in the workplace:

Exploring its effects on occupational stress and organizational commitment.

The International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 10, 327342.

Ramos, N. S., Fernandez-Berrocal, P., & Extremera, N. (2007). Perceived emotional

intelligence facilitates cognitive-emotional processes of adaptation to an acute

stressor. Cognition and Emotion, 21, 758772.

Roberts, R. D., MacCann, C., Matthews, G., & Zeidner, M. (2010). Emotional

intelligence: Toward a consensus of models and measures. Social and

Personality Psychology Compass, 4, 821840.

Saab, P. G., Matthews, K. A., Stoney, C. M., & McDonald, R. H. (1989). Premenopausal

and postmenopausal women differ in their cardiovascular and neuroendocrine

responses to behavioral stressors. Psychophysiology, 26(3), 270280.

914

T.R. Schneider et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 55 (2013) 909914

Salovey, P., Bedell, B., Detweiler, J., & Mayer, J. (1999). Coping intelligently:

Emotional intelligence and the coping process. In C. R. Snyder (Ed.), Coping: The

psychology of what works (pp. 141164). New York: Oxford University Press.

Salovey, P., Kokkonen, M., Lopes, P., & Mayer, J. D. (2004). Emotional intelligence:

What do we know? In A. S. R. Manstead, N. H. Frijda, & A. H. Fischer (Eds.),

Feelings and emotions: The Amsterdam symposium (pp. 319338). New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Schneider, T. R. (2004). The role of Neuroticism on psychological and physiological

stress responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 795804.

Schneider, T. R. (2008). Evaluations of stressful transactions: Whats in an

appraisal? Stress and Health, 24, 151158.

Schulze, R., Wilhelm, O., & Kyllonen, P. C. (2007). Approaches to the assessment of

emotional intelligence. In G. Matthews, M. Zeidner, & R. D. Roberts (Eds.), The

science of emotional intelligence: Knowns and unknowns (pp. 199229). New

York, NY, US: Oxford University Press.

Sherwood, A., Allen, M. T., Fahrenburg, J., Kelsey, R. M., Lovallo, W. R., & van

Doornen, L. J. P. (1990). Methodological guidelines for impedance cardiography.

Psychophysiology, 27, 123.

Stroud, L., Salovey, P., Woolery, A., & Epel, E. (2002). Perceived emotional

intelligence, stress reactivity, and symptom reports: Further explorations

using the trait meta-mood scale. Psychology and Health, 17, 611627.

Tomaka, J., & Blascovich, J. (1994). Effects of justice beliefs on cognitive appraisal of

and subjective, physiological, and behavioral responses to potential stress.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 440732.

Tomaka, J., Blascovich, J., Kelsey, R., & Leitten, C. (1993). Subjective, physiological,

and behavioral effects of threat and challenge appraisal. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 65, 248260.

Van Rooy, D. L., Alonso, A., & Viswesvaran, C. (2004). Group differences in emotional

intelligence scores: Theoretical and practical implications. Personality and

Individual Differences, 38, 689700.

Vollrath, M., & Torgersen, S. (2000). Personality types and coping. Personality and

Individual Differences, 29, 367378.

Watson, D., Clark, L., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief

measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 10631070.

Zajonc, R. B. (1998). Emotions. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.). The

handbook of social psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 591632). New York: McGraw-Hill. 4th

ed..

Zeidner, M., Roberts, R. D., & Matthews, G. (2004). The emotional intelligence

bandwagon: Too fast to live, too young to die? Psychological Inquiry, 15,

239248.

You might also like

- Emotional Intelligence and Resilience PDFDocument6 pagesEmotional Intelligence and Resilience PDFGODEANU FLORINNo ratings yet

- Character Strengths & Cognitive Vulnerabilities - Huta & Hawley (2010)Document23 pagesCharacter Strengths & Cognitive Vulnerabilities - Huta & Hawley (2010)Miguel Angel Alemany NaveirasNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Birth Order On Psychological Resilience Among Adolescents Exposed To Domestic ViolenceDocument14 pagesThe Effects of Birth Order On Psychological Resilience Among Adolescents Exposed To Domestic ViolencelugtutjayNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence and Psychological Resilience To Negative Life EventsDocument6 pagesEmotional Intelligence and Psychological Resilience To Negative Life EventsBogdan Hadarag100% (1)

- J Paid 2006 09 003Document13 pagesJ Paid 2006 09 003kinemasNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence and Perceived StressDocument14 pagesEmotional Intelligence and Perceived StressAnna MindovaNo ratings yet

- 2011 - How Psychosocial Resources Enhance Health and WellbeingDocument23 pages2011 - How Psychosocial Resources Enhance Health and WellbeingSadhana KrishNo ratings yet

- Negative Affect and Overconfidence: A Laboratory InvestigationDocument41 pagesNegative Affect and Overconfidence: A Laboratory InvestigationAngus SadpetNo ratings yet

- Hu 2015Document10 pagesHu 2015Havadi KrisztaNo ratings yet

- Ciarrochi Scott PID Relations Between Social Emotional Competence Mental Health 2003 PDFDocument17 pagesCiarrochi Scott PID Relations Between Social Emotional Competence Mental Health 2003 PDF5l7n5No ratings yet

- Experiencing Job Burnout: The Roles of Positive and Negative Traits and StatesDocument25 pagesExperiencing Job Burnout: The Roles of Positive and Negative Traits and StatesMonica PalaciosNo ratings yet

- 2004 Neuroticismo Extraversion y Estres PostraumaticoDocument20 pages2004 Neuroticismo Extraversion y Estres PostraumaticoGuillermo E Arias MNo ratings yet

- Tarea 33Document8 pagesTarea 33marielisNo ratings yet

- HARDBOUND Thesis 2018 1 PDFDocument65 pagesHARDBOUND Thesis 2018 1 PDFHamimah Bint AliNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence, Coping and Exam-Related Stress in Canadian Undergraduate StudentsDocument9 pagesEmotional Intelligence, Coping and Exam-Related Stress in Canadian Undergraduate StudentsezaNo ratings yet

- CrumSaloveyAchor RethinkingStress JPSP2013 PDFDocument18 pagesCrumSaloveyAchor RethinkingStress JPSP2013 PDFAbe AdanNo ratings yet

- Positive and Negative Affective Outcomes of Occupational LStressDocument7 pagesPositive and Negative Affective Outcomes of Occupational LStressAndra Corina CraiuNo ratings yet

- Stress, Social Support and Fear of DisclosureDocument15 pagesStress, Social Support and Fear of DisclosureannasescuNo ratings yet

- Emotions in Sport PDFDocument10 pagesEmotions in Sport PDFagarcia18No ratings yet

- 2013PANAS Affect Balance ScoreDocument6 pages2013PANAS Affect Balance ScoreCristina Maria BostanNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence and Psychological Resili 2011 Personality and IndividDocument6 pagesEmotional Intelligence and Psychological Resili 2011 Personality and IndividTorburam LhamNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence As A Moderator of Stressor-Mental Health Relations in Adolescence. Evidence For SpecificityDocument6 pagesEmotional Intelligence As A Moderator of Stressor-Mental Health Relations in Adolescence. Evidence For SpecificityBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- (Emotion Focused Coping and Stress Are Predictors of Well-Being) Karademas 2007Document11 pages(Emotion Focused Coping and Stress Are Predictors of Well-Being) Karademas 2007Yasmin NNo ratings yet

- Car Thy 2009Document14 pagesCar Thy 2009AoiNo ratings yet

- Emotion Beliefs in Social Anxiety Disorder: Associations With Stress, Anxiety, and Well-BeingDocument10 pagesEmotion Beliefs in Social Anxiety Disorder: Associations With Stress, Anxiety, and Well-BeingLukas Dwiputra TesanNo ratings yet

- 21 2006 The Dynamic Process of Life SatisfactionDocument30 pages21 2006 The Dynamic Process of Life SatisfactionCristina Maria BostanNo ratings yet

- Brackett... PT BiblioDocument16 pagesBrackett... PT BiblioJules IuliaNo ratings yet

- Veage Ciarrochi and Heaven 2011 Paid Importance Pressure Success Dimensio of Values and Their Links To PersonalityDocument6 pagesVeage Ciarrochi and Heaven 2011 Paid Importance Pressure Success Dimensio of Values and Their Links To PersonalityIvanNo ratings yet

- Elderly ResearchDocument20 pagesElderly ResearchgejibNo ratings yet

- Arti Seminario 3Document6 pagesArti Seminario 3Rei KonaeNo ratings yet

- Effect of Mood On Problem Solving 1Document21 pagesEffect of Mood On Problem Solving 1LolaManijaDanijaNo ratings yet

- (10-15) A Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Self EsteemDocument6 pages(10-15) A Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Self Esteemiiste100% (1)

- A Critical Evaluation of The Emotional Intelligence Construct) 2000Document23 pagesA Critical Evaluation of The Emotional Intelligence Construct) 2000danion06No ratings yet

- Feeling Good and Doing Great The RelatioDocument13 pagesFeeling Good and Doing Great The RelatioHenry WijayaNo ratings yet

- Brief History of Emotional IntelligenceDocument5 pagesBrief History of Emotional IntelligenceshubhamNo ratings yet

- Be Happy The Role of Resilience Between PDFDocument14 pagesBe Happy The Role of Resilience Between PDFyulia yasniNo ratings yet

- 33.fear Anger and RiskDocument14 pages33.fear Anger and RiskPaulo FerreiraNo ratings yet

- ED602396Document34 pagesED602396Mekhla PandeyNo ratings yet

- 10 ArticolDocument15 pages10 ArticolAnaBistriceanuNo ratings yet

- Afirmacion de ValoresDocument7 pagesAfirmacion de ValoresjuliNo ratings yet

- Tugade2004 PDFDocument14 pagesTugade2004 PDFDiego AmayaNo ratings yet

- Cann and Collette 2014Document16 pagesCann and Collette 2014Shinichi Conan HaibaraNo ratings yet

- Klmpok 2Document17 pagesKlmpok 2Alfan HabibNo ratings yet

- Dolbier Smith Steinhardt JCC (112208)Document28 pagesDolbier Smith Steinhardt JCC (112208)YogineePawanNo ratings yet

- Personalitatii ArticolDocument8 pagesPersonalitatii ArticolCojocaru Cristina IoanaNo ratings yet

- Child Abuse & Neglect: Sharon MC Elroy, David HeveyDocument11 pagesChild Abuse & Neglect: Sharon MC Elroy, David HeveyAndreea PalNo ratings yet

- Psychological Resilience, Positive Emotions, and Successful Adaptation To Stress in Later LifeDocument20 pagesPsychological Resilience, Positive Emotions, and Successful Adaptation To Stress in Later LifeEsraa EldadNo ratings yet

- I. Background/Objectives and GoalsDocument2 pagesI. Background/Objectives and GoalsJilmilyn MolenoNo ratings yet

- Role of Self-Control Strength in The Relation Between Anxiety and Cognitive PerformanceDocument13 pagesRole of Self-Control Strength in The Relation Between Anxiety and Cognitive PerformanceCatarina C.No ratings yet

- Brosur Diet HipertensiDocument31 pagesBrosur Diet HipertensiLia Rizqa Amelia MahmudNo ratings yet

- The Dimensional Structure of The Emotional Self-Efficacy Scale (ESES)Document8 pagesThe Dimensional Structure of The Emotional Self-Efficacy Scale (ESES)Andresa SouzaNo ratings yet

- Samimi Annotated Bibliography 1Document13 pagesSamimi Annotated Bibliography 1api-245462704100% (1)

- Positive ThinkingDocument11 pagesPositive ThinkingJordan BradsherNo ratings yet

- Watson (1988) - Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect The PANAS ScalesDocument8 pagesWatson (1988) - Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect The PANAS ScalesElwood BluesNo ratings yet

- Pride and Perseverance The Motivational Role of PrideDocument11 pagesPride and Perseverance The Motivational Role of PrideJimmy ReturanNo ratings yet

- Journal of Experimental Psychopathology: Justin W. Weeks, Peggy M. ZoccolaDocument23 pagesJournal of Experimental Psychopathology: Justin W. Weeks, Peggy M. Zoccolaselamet apriyantoNo ratings yet

- Profiles of Resilience and Psychosocial Outcomes Among Young Black Gay and Bisexual MenDocument17 pagesProfiles of Resilience and Psychosocial Outcomes Among Young Black Gay and Bisexual MenFirmanNo ratings yet

- Nikolaou 2002Document16 pagesNikolaou 2002patriciamouropereiraNo ratings yet

- Running Head-Emtion and TrustDocument56 pagesRunning Head-Emtion and Trustapi-3828653No ratings yet

- Measurement and Derivation of Aerps/Aefs: Omitted Stimulus Response in Long-Latency Aerp Responses, Below)Document37 pagesMeasurement and Derivation of Aerps/Aefs: Omitted Stimulus Response in Long-Latency Aerp Responses, Below)Bogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- FST LD Psy403 MSC Session 1Document26 pagesFST LD Psy403 MSC Session 1Bogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Preparing Predicts Recall. An Event-Related Potential (ERP) Study (Dissertation For MSC)Document79 pagesPreparing Predicts Recall. An Event-Related Potential (ERP) Study (Dissertation For MSC)Bogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- MSC Handbook 2020-21Document29 pagesMSC Handbook 2020-21Bogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- FST601 Report Quiz 2019 v1Document2 pagesFST601 Report Quiz 2019 v1Bogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- PSYC403 Handbook 2020Document15 pagesPSYC403 Handbook 2020Bogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Inferior Parietal Lobule Contributions To 1 PDFDocument13 pagesInferior Parietal Lobule Contributions To 1 PDFBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice-2006-Garrison-204-12 PDFDocument10 pagesYouth Violence and Juvenile Justice-2006-Garrison-204-12 PDFBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Resilience, Vulnerability and Mental HealthDocument4 pagesResilience, Vulnerability and Mental HealthBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- CWA Spot The Errors PGT Ethics Application (2017)Document15 pagesCWA Spot The Errors PGT Ethics Application (2017)Bogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- CWA Spot The Errors PGT Ethics Application (2017)Document15 pagesCWA Spot The Errors PGT Ethics Application (2017)Bogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Completed Example (2017) UG PGT Ethics Form Psychology DeptDocument12 pagesCompleted Example (2017) UG PGT Ethics Form Psychology DeptBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Inferior Parietal Lobule Contributions To 1 PDFDocument13 pagesInferior Parietal Lobule Contributions To 1 PDFBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Completed Example (2017) UG PGT Ethics Form Psychology DeptDocument12 pagesCompleted Example (2017) UG PGT Ethics Form Psychology DeptBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice-2006-Articles-215-6 PDFDocument3 pagesYouth Violence and Juvenile Justice-2006-Articles-215-6 PDFBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice-2006-Chapman-170-84 PDFDocument16 pagesYouth Violence and Juvenile Justice-2006-Chapman-170-84 PDFBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice-2006-Chapman-170-84 PDFDocument16 pagesYouth Violence and Juvenile Justice-2006-Chapman-170-84 PDFBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) - Dimensionality and Age-Related Measurement Invariance With Australian CricketersDocument11 pagesThe Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) - Dimensionality and Age-Related Measurement Invariance With Australian CricketersBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Emotional Intelligence (EI) On Coping and Mental Health in Adolescence. Divergent Roles For Trait and Ability EIDocument11 pagesThe Influence of Emotional Intelligence (EI) On Coping and Mental Health in Adolescence. Divergent Roles For Trait and Ability EIBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Resilience and Mental HealthDocument17 pagesResilience and Mental HealthMarlenxcaNo ratings yet

- Sociocultural Factors, Resilience, and Coping. Support For A Culturally Sensitive Measure of ResilienceDocument16 pagesSociocultural Factors, Resilience, and Coping. Support For A Culturally Sensitive Measure of ResilienceBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) - Testing The Invariance of A Uni-Dimensional Resilience Measure That Is Independent of Positive and Negative AffectDocument5 pagesThe Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) - Testing The Invariance of A Uni-Dimensional Resilience Measure That Is Independent of Positive and Negative AffectBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Resilience, Competence, and CopingDocument5 pagesResilience, Competence, and CopingBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence Predicts Adolescent Mental Health Beyond Personality and Cognitive AbilityDocument6 pagesEmotional Intelligence Predicts Adolescent Mental Health Beyond Personality and Cognitive AbilityBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Relationship of Resilience To Personality, Coping, and Psychiatric Symptoms in Young AdultsDocument15 pagesRelationship of Resilience To Personality, Coping, and Psychiatric Symptoms in Young AdultsBogdan Hadarag100% (1)

- Factors Associated With Resilience in Healthy AdultsDocument4 pagesFactors Associated With Resilience in Healthy AdultsBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence, Emotions, and Feelings of Support Staff Working With Clients With Intellectual Disabilities and Challenging Behavior. An Exploratory StudyDocument8 pagesEmotional Intelligence, Emotions, and Feelings of Support Staff Working With Clients With Intellectual Disabilities and Challenging Behavior. An Exploratory StudyBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence As A Moderator of Stressor-Mental Health Relations in Adolescence. Evidence For SpecificityDocument6 pagesEmotional Intelligence As A Moderator of Stressor-Mental Health Relations in Adolescence. Evidence For SpecificityBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Barge 180Ft Deck Load Capacity & Strength-Rev1Document52 pagesBarge 180Ft Deck Load Capacity & Strength-Rev1Wahyu Codyr86% (7)

- Latihan Soal Report TextDocument28 pagesLatihan Soal Report TextHidayatul HikmahNo ratings yet

- Catalogo Smartline Transmitter Family Ferrum Energy 变送器Document12 pagesCatalogo Smartline Transmitter Family Ferrum Energy 变送器peng chaowenNo ratings yet

- Angle of Elevation and Depression For Video LessonDocument35 pagesAngle of Elevation and Depression For Video LessonAlma Delos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Renal New Growth - NCM 103 - or CaseDocument19 pagesRenal New Growth - NCM 103 - or CasePat EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Sale of Property When - KP AstrologyDocument2 pagesSale of Property When - KP Astrologyprajishvet100% (1)

- Dynamic Test Report of DECR-S Excitation Devices: ExperimenterDocument14 pagesDynamic Test Report of DECR-S Excitation Devices: ExperimenterSalmanEjazNo ratings yet

- Final Cor 011 Reviewer PDFDocument104 pagesFinal Cor 011 Reviewer PDFMary JuneNo ratings yet

- Basic Pancakes Recipe - Martha StewartDocument37 pagesBasic Pancakes Recipe - Martha Stewartkrishna kumarNo ratings yet

- HorticultureDocument12 pagesHorticultureवरुण राठीNo ratings yet

- CTL Project Developer Perspective Coal - To - Liquids CoalitionDocument27 pagesCTL Project Developer Perspective Coal - To - Liquids Coalitiondwivediashish2No ratings yet

- Dave Graham Literature CatalogDocument640 pagesDave Graham Literature CatalogPierce PetersonNo ratings yet

- A MCQ: Si - No Sub Topics NameDocument2 pagesA MCQ: Si - No Sub Topics NameInzamamul Haque ShihabNo ratings yet

- Introduction To ProbabilityDocument50 pagesIntroduction To ProbabilityJohn StephensNo ratings yet

- Al Khudari Company Profile FP PDFDocument14 pagesAl Khudari Company Profile FP PDFAnonymous bgYdp4No ratings yet

- Therelek - Heat Treatment ServicesDocument8 pagesTherelek - Heat Treatment ServicesTherelek EngineersNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Food Analysis2020Document2 pagesIntroduction To Food Analysis2020Ĝĭdęŷ KîřöşNo ratings yet

- Listening DictationDocument3 pagesListening DictationThảo ĐinhNo ratings yet

- Davao Region Slogan Reflective EssayDocument4 pagesDavao Region Slogan Reflective EssayDonna Elaine OrdoñezNo ratings yet

- Tugas Topic 4 Devi PermatasariDocument8 pagesTugas Topic 4 Devi PermatasariMartinaNo ratings yet

- REM Geo&Man Comp 2016Document350 pagesREM Geo&Man Comp 2016youungNo ratings yet

- En 13757 3 2018 04Document104 pagesEn 13757 3 2018 04Hélder Vieira100% (1)

- Cbse Class 6 Science Notes Chapter 13Document4 pagesCbse Class 6 Science Notes Chapter 13rohinimr007No ratings yet

- BDSM List FixedDocument4 pagesBDSM List Fixedchamarion100% (3)

- PX 150 UsaDocument138 pagesPX 150 UsaramiroNo ratings yet

- Form 03B Heritage Bell 1Document2 pagesForm 03B Heritage Bell 1ValNo ratings yet

- 2CCC413001C0203 S800Document60 pages2CCC413001C0203 S800Sang SekNo ratings yet

- Okumas Guide To Gaijin 1Document90 pagesOkumas Guide To Gaijin 1Diogo Monteiro Costa de Oliveira SilvaNo ratings yet

- Ultrasonic Inspection of Welds in Tubes & Pipes: Educational NoteDocument13 pagesUltrasonic Inspection of Welds in Tubes & Pipes: Educational NoteleonciomavarezNo ratings yet

- Marcelo - GarciaDocument6 pagesMarcelo - GarciaNancy FernandezNo ratings yet