Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Walsh, 2009

Uploaded by

Jbl2328Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Walsh, 2009

Uploaded by

Jbl2328Copyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Nursing Practice 2009; 15: 231240

REVIEW PAPER

Interventions to reduce psychosocial disturbance

following humanitarian relief efforts involving

natural disasters: An integrative review

ijn_1766

231..240

Denise Susan Walsh MSN RN

Doctoral Candidate, University of Connecticut, Storrs, Connecticut, USA

Accepted for publication April 2009

Walsh DS. International Journal of Nursing Practice 2009; 15: 231240

Interventions to reduce psychosocial disturbance following humanitarian relief efforts involving

natural disasters: An integrative review

Because of the increased level of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) reported post disaster work, it is imperative that

governmental and non-governmental agencies consider predisaster training of volunteers in not only clinical skills, but also

communication and team building. When these concepts are combined with ongoing support post disaster, a decrease in

the frequency and severity of PTSD has been reported. A review of 12 studies examined responses of relief workers to

various disaster situations. Experiences were extracted, categorized, and a data reduction model was developed to

illustrate the characteristics of the experiences and subsequent interventions that were reported. Three interventions that

positively affected the responses of relief workers to disaster experiences emerged: debriefing, team building and

preparation.

Key words: disaster planning, post-traumatic stress disorder, relief work, rescue work.

INTRODUCTION

A thousand eyes that see the pain in all the corners of the

universe and a thousand arms to reach out to all corners of the

universe to extend help

Tibetan Iconography

On the morning of 26 December 2004, the lives of

300 000 people were forever lost. An earthquake off the

coast of Indonesia caused a tsunami to cross the Indian

Ocean from Sumatra to Africa. Three waves traversed the

ocean at a speed of 500 mph unbeknownst to the world.

The resulting damage affected 12 countries, and was

Correspondence: Denise Susan Walsh, 217 Northwood Road, Fairfield,

CT 06825, USA. Email: walshroyal@aol.com

doi:10.1111/j.1440-172X.2009.01766.x

responsible for 175 000 deaths with 125 000 people still

missing and presumed dead. One million people were

displaced from their homes, and 500 000 people were

injured. Within hours the tsunami had directly affected

the lives of 1.8 million people both physically and psychologically, and millions more indirectly as the economies of

these countries were devastated.1

The Ampara District on the east coast of Sri Lanka was

hardest hit. A poor area already suffering from many years

of civil war between the Tamils in the North, and the

Singhalese in the South, this region reported seven out of

10 family members killed that morning and 79 000 people

had their homes destroyed. When the tsunami came

ashore in Sri Lanka the three waves measured 10, 20 and

30 feet high respectfully with a force never before seen in

the world.

2009 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

232

The humanitarian response to this natural disaster was

immediate and overwhelming. On the northeast coast of

Sri Lanka, United Nation Organizations provided tents to

the thousands of persons without any means of shelter,

and Oxfam International focused on bringing clean water

and toilet facilities to the tent cities that were quickly

rising along the coastline. Volunteer medical teams from

non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in the USA,

Australia, Canada and the UK coordinated surveillance

programmes for tracking malaria, tuberculosis and

cholera in the refugee camps.

The focus of the relief effort was treatment of injuries,

both physiological and psychological, and the settlement

of the growing refugee population. When the relief

workers arrived on the scene their senses were

assaulted.2 One volunteer reported that no amount of

field experience could have prepared you for the situation

of working at the tsunami. Observing devastation and

suffering on a mass scale and trying to function to the best

of your abilities with limited resources is a unique,

demanding experience.3

Increasingly, the world is becoming interconnected

and dependent upon the global community to offer assistance from challenges posed by disasters. As health-care

professionals respond to emergency situations and care for

trauma victims, relief agencies responsible for these volunteers must focus on their preparation of, and readjustment to, life after their term of service. Medecins Sans

Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders) has been sending

volunteers since 1971 to the most dangerous localities in

the world to provide medical help to those in crisis. The

Nobel Peace Prize winning organization is criticized for

the lack of effort it expends to readjust their members to

life at home and work upon their return. The organization

does a good job preparing volunteers for a mission, but

no preparation to come home. This lack of preparation

results in the inability to relate to home life and work life

for weeks and sometimes months.4

The relief workers who answered the call to action in

Sri Lanka were not only exposed to the stress of the

disaster, but also to the stress of the role of caregiver to

the victims.5 The effects of these stressors can ultimately

lead to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).6 Current

research shows a critical need to examine the impact on

the practice of health-care volunteers returning from

disaster relief and the role of humanitarian organizations

in supporting and protecting their volunteers from developing stress-related disorders. By exploring the shared

2009 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

DS Walsh

experiences of relief workers after their return from a

humanitarian crisis, and identifying interventions, it is

hoped that organizations will incorporate these findings

into a re-entry programme to home and work.

The purpose of this review is to describe and synthesize

the research of the characteristics of the psychosocial

responses of relief workers and identify interventions that

reduce the occurrence and severity of PTSD following

these experiences. Specific aims of the review are (i) to

identify psychosocial effect of the experience of relief

work; (ii) and describe interventions that have been identified in reducing the severity of psychosocial disturbances

upon return. The implications for research are presented.

METHOD

Review methodologies proposed by Whittemore and

Knafl were used to analyse and synthesize research related

to relief work experiences and subsequent interventions.7

The framework consists of a clear identification of the

problem supported by a well-defined literature search,

data evaluation and analysis and synthesis of results. With

the assistance of a research librarian a thorough search was

undertaken using multiple medical/nursing, health and

social science journals, online sites, news sites, case

reports and unpublished manuscripts. All searches were

limited to English language publications. Exhaustive

searches of CINAHL, Ovid, Global Health Database,

PsychINFO, MEDLINE and REFWorks databases were

undertaken using the following key concepts: Tsunami,

relief workers, PTSD, humanitarian nursing, psychosocial impact of disaster care, natural disasters,

experience of disaster nursing, support after trauma.

Both an ancestral method of tracking information from

one citation to another as well as the descendency method

of gathering information based upon central topics were

used in the studies included in the review.8

Criteria for inclusion included: (i) those empirical

research studies that measured certain characteristics of

post relief work with scales or instruments; or (ii) the

qualitative research of the experiences of the workers in

their own voices. A total of 33 articles were reviewed

with 12 studies meeting the inclusion criteria. Jackson

suggests that an integrative review consist of a broad

stratum of data that can illustrate different interactions of

the characteristics of the research.9 The researcher concentrated on the humanitarian efforts of professional and

non-professional workers, and knowingly excluded military or national defence responses. A majority of the

Reducing Psychosocial Disturbances

research involved the response of survivors of disasters.

These studies were eliminated from the review.

Research reviewed included relief workers from professional and non-professional backgrounds, and both

natural and man-made disasters. Multiple research designs

and methods were represented in the twelve manuscripts.

Some of the methods were questionnaires with open and

closed question format, focus groups, case reports, interviews, thematic and content analysis, and quantitative

rating scales for specific diagnoses. A data collection tool

was designed to assist in analysing each research study.

Studies were thoroughly read and the following characteristics were identified and organized using an Excel

spreadsheet: the purpose of the study, the sample,

research methodology, procedure for data collection and

results. A table was developed with a concise description

of each of the characteristics (see Table 1). From this

table, a matrix was constructed to evaluate and synthesize

the results of the research studies using two

variablesthe quality of the methodology and the themes

that were identified. The purpose in grouping the studies

was to capture both the empirical results and the qualitative experiences of the workers, and identify shared points

of interests.

In reviewing the studies, results were extracted and

categorized, and a series of interrelated patterns emerged

describing the psychosocial responses of relief workers in

a disaster situation. Subgroups were identified and compared item by item. A one-page synopsis was constructed

of each study and commonalities were integrated into a

holistic description of the workers responses.

Validity is threatened in integrative research when

important details of the research studies are incorrectly

interpreted.8 To address this threat, the literature search

consisted of primary sources and an analysis strategy was

developed that synthesized information in an unbiased

method. A systematic, reliable coding procedure was used

to analyse and synthesize the information thereby ensuring

validity of results.7

RESULTS

Review of these 12 studies supports the value of integrating results from both qualitative and quantitative research

to synthesize a more complete understanding of the

combined research results. This review included three

quantitative studies, eight qualitative studies and one

mixed methodology study.

233

The research studies sampled were from a variety of

disciplines, disaster circumstances and sample groups.

The time frame ranged from 1984 to 2007 with diverse

locations of disasters researchedGermany, Sri Lanka,

Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, New Zealand, Iran, Israel,

Australia and the USA. The sample group was also divided

between professional and non-professional workers,

including fire fighters, physicians, nurses, mental health

personnel, rescue workers and lay volunteers.

The inclusive sample from the twelve studies consisted

of a total of 1523 persons. A total of 332 (22%) participants had no prior experience working at disaster sites,

770 (50%) participants had professional experience

(health-care workers, fire fighters, rescue workers) and

421 (28%) participants were enlisted as a comparison

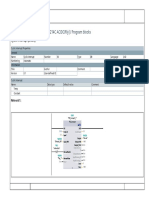

group in one research study. A data reduction model was

formatted to organize the characteristics of the experiences in the studies and integrate specific interventions

that were identified in the research (see Fig. 1). Three

interventions emerged that affected the responses of relief

workersdebriefing, team building and preparation.

Psychosocial effects

Workers who responded to the call to action in a humanitarian crisis exposed themselves to not only physical but

also psychological danger. The experience resulted in

highly reported sleep disturbances and nightmare,1012,15,18

and a marked increase in feelings of helplessness, anxiety

and increased arousal.5,14,15,18

Three studies reported a measurable range (24

63.6%) of participants exhibiting depressive symptomology. The self-rated DSM PTSD-IV Scale19 and Zung SelfRating Depression Scale20 was used by Fullerton et al.11 to

compare 207 disaster workers and a comparison group of

421 non-participating workers. The study reported 42%

of the exposed disaster workers at the crash of a commercial DC-10 airliner developed PTSD. The ClinicianAdministered PTSD Scale-I21 interview was administered

to relief workers returning from the tsunami in 2004 with

63.6% of the sample exhibiting at least one of the

reported symptoms.15 Guo et al.14 assessed relief workers

following an earthquake in Taiwan and determined that

24.6% of the volunteers (20% of professional verses 33%

non-professional) reported PTSD using the Chinese

version of the Davidson Trauma Scale22 and Startle, Physiological Arousal, Anger and Numbness Scale.23

It is important to note that one study followed workers

at high risk for developing PTSD year a 3-year period.12 A

2009 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

Purpose

Describe experience of

volunteer mental health

workers at brushfire

disasterphysical and

psychological responses

Investigate psychological

responses to thematic

stressworkers at air

show disaster

To investigate the

psychological impact of fire

fighters to traumatic stress

Investigate the

phenomenology of PTSD

Following natural disaster

To better plan for the

health of disaster

volunteers, researched

PTSD, depression in

disaster workers

Study occurrence of PTSD

in professional/

non-professional rescue

workers focusing

similarities/differences in

the groups

Author, year, place

Berah et al.,10 1984,

New Zealand

Brandt et al.,5 1995,

Germany

Fullerton et al.,11 1992,

USA

2009 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

McFarlane,12 1988,

Australia

Fullerton et al.,13 2004,

USA

Guo et al.,14 2004,

Taiwan

252 rescue workers (85

non-professional and 167

professional)

207 exposed disaster

workers and 421

unexposed comparison

group

45 firefighters from 315 at

high risk for developing

PTSD

2 groups of fire fighters

total 25 participants

252 respondents with 99

attending voluntary

debriefing sessions

19 workers from Prince

Henry Hospital,

Melbourne

Sample

Table 1 Published research articles involving the experience of relief workers

DTS-C Trauma Scale

SPAN-C

PTSD-IV and Zung

Self-rating Depression

Scale and comparison

Structured interview

GHQ, IES Scale

Debriefing groups

Descriptive studyopen

thematic analysis of case

studies

Questionnaire with open/

closed ended questions

thematic analysis

Method

On-scene workers were

offered psychological

debriefing, followed by a

questionnaire

Both groups examined at

2, 7 and 13 months after

disaster

Interview firefighters who

worked at bushfires at 8-,

11- and 29-month intervals

Case reports developed

from 8 debriefing sessions

6 weeks after the disaster

questionnaire distributed

with debriefing session held

1 week after returning

questionnaire

4 weeks after working at

disaster site, questionnaire

completed and

anonymously returned

Procedure

Rescue workers, even

those trained, experience a

higher level of stress,

leading to mental health

problems

Disaster workers increased

rate of PTSD, depression,

seek medical assistance at a

higher rate

Pattern of chronic and

disabling PTSD with

attention disturbances, or

panic symptoms in 16 of

50 firefighters

4 characteristic

responseshelplessness,

guilt, fear of unknown,

identify with the victims

Feelings of helplessness and

guilt, and camaraderie

among workers

debriefing session helped

integrate experience

Team felt shocked, tired,

helpless, stressedused

debriefing methods offered

in community

Results

234

DS Walsh

To explore the experience

of disaster relief in the

Bam earthquake as seen

from Iranian nurses

Identify beliefs, concerns

of RNs working in

hospitals designated as

receiving sites during

emergencies

Describe the perception,

reaction, feelings of RNs

who care for victims of

terrorist attacks, and

recommend policy for RN

trauma training

Nasrabadi et al., 162007,

Iran

OBoyle et al.,17 2006,

Minnesota, USA

Riba and Reches,18 2002,

Israel

60 RNs from the ED,

OR, ICU and Imaging

departments

33 hospital RNs who

work in ED or critical

care units at least 8 h

every 2 weeks, employed

6 months

13 Iranian RNs with BSN,

2 weeks experience as

RNs during Bam disaster,

and 12 years clinical

experience as RNs

33 team members

Ongoing and summative

content analysis were

used to develop and

refine themes

Qualitative study using

focus groups

Qualitative,

semi-structured serial

interview analysed by

latent content method

CAPS-1 PTSD Interview

scale

Focus groups met on 4

occasions, and staff were

asked to describe their

experiences. Responses

were recorded

Focus groups of 29 met

during coffee breaks or

lunch for 3045 min

discussing concerns, coping

mechanisms to function

during a crisis

Each nurse was

interviewed for 4590 min

and tape-recorded. An

interview guide was used

to focus the interview

Interviews performed by

after tsunami

RNs described 4 stages of

involvementcall up of

staff to the hospital,

waiting for casualties,

treating victims and

incident closure. Need to

broaden RN training and

caring for caregivers.

Frustration, guilt and

depression were described

RNs felt unready to cope

with bioterrorism, felt an

increased loss of control,

loss of freedom, decreased

safety, concern of

abandonment by hospital,

no freedom to leave,

insufficient protective

equipment

3 themes emerged: need

for prepared protocols,

teambuilding and establish

comprehensive training

programmes in disaster

relief nursing.

PTSD diagnosed in 24.2%

participants with > 3

experiences

BSN, Bachelor of Nursing; CAPS-1, Clinician Administered PTSD Scale-1; DTS-C, Chinese version of the Davidson Trauma Scale; ED, emergency department; GHQ, General Health

Questionnaire; ICU, intensive care unit; IES, Impact of Event Scales; OR, Operating Room; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; RN, registered nurse; SPAN-C, Startle, Physiological

Arousal, Anger and Numbness Scale.

Identify PTSD in relief

workers after tsunami in

Asia

Armagan et al.,15 2006,

Turkey

Reducing Psychosocial Disturbances

235

2009 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

236

DS Walsh

Data Reduction Model

Psychosocial factors

Physiological changes

Preventative measures

Attention deficit

Voluntary session

Debriefing

Seek emotional care

Social support

Cognitive integration of

the experience

Develop emotional ties

to victims

Relationship with peers

Emotional distancing

Effective communication

Bond with co-worker

Alliance among workers

Need for centralized

leadership

Coordination of workers

Importance of infrastructure

Seamless care

Team building

Utilization of volunteers

React in precise manner

Gaps in medical/nursing

education

Culturally appropriate

Formal education

Preplanned protocols

Leadership training

Preparation

Clinical/resource readiness

Institutional support

Fear of abandonment

Commitment

Clear chain of command

Figure 1. Data reduction model.

pattern of chronic and disabling PTSD emerged within the

group emphasized by attention disturbances, panic symptoms and nightmares. The fact that attention deficit was

noted at the 8-month mark and also as late as 42 months

accentuates the need for ongoing intervention if the

severity of the effects of relief work is to be reduced.

Qualitative studies included focus groups with registered nurses after terrorist attacks in Israel,18 interviews

with firefighters after two Australian brushfires10,12 and

descriptive studies following an air show crash.5

Although the psychosocial responses from the workers

were consistent in all the research studies, the circumstances surrounding each crisis were different. The

2009 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

responses by the staff in the focus groups further

described burnout and frustration, guilt and anxiety over

surviving.18 Mental health workers interviewing the individuals and families working at the bushfires reiterated

the emotional toll on workers as reported including

shock and confusion.

The act of emotional distancing is an adaptive process

that disengages workers from the experience at hand.

Distancing places the workers at risk for exhaustion as

they continue to function as an uninvolved person. Three

studies noted an increase in stress levels of workers after

instinctively divorcing themselves from the situation.5,11,18

After the patients were cared for, the staff turned their

Reducing Psychosocial Disturbances

emotions back on, and reported a need to verbalize their

experience.

Debriefing as an intervention

The need for preventative interventional measures11 was

described in the forms of voluntary sessions and meetings

offered by organizations,11,18 as well as participants

seeking emotional care and social support on their

own.10,13,24 Post-tsunami workshops in Sri Lanka utilized

the concept of support groups by focusing on training

local young adults who were indigenous to the villages to

conduct debriefing sessions.25 Although no formal measurement was obtained after the programme, there was a

positive reception of the education component of the programme, which included information related to growth

and development, substance abuse and suicide. Feedback

consisted of verbal reports and observations from the

coordinators and the project directors.

The use of support groups to cognitively integrate the

experience was also described by Fullerton et al.11 in a

study involving an airplane crash in Iowa and fire in New

York City. Social support after the situations and the

opportunity for workers to share their experiences were

seen as important. Relief workers reported developing

emotional ties to the victims.5,11 When workers felt an

emotional connection with the victims, they began to

visualize themselves or their family members as victims.

This process placed the workers at risk for exhaustion as

they continued to try to function as an uninvolved person,

and increased the stress of working at the disaster site.

A summation of the individual themes was formulated

into three subgroups: preventative measures, voluntary

sessions and social support (see Fig. 1). A higher level of

abstraction resulted in the general intervention of debriefing. Debriefing offered a venue for ventilating emotions

and reduced the impact of the stress on relief workers

lives.10

Team building as an intervention

Effective communication and coordination of workers

was underscored throughout the research for its importance in reducing the severity of psychosocial adjustment.

The relationship one held with their peers,11,14 and the

development of bonds with co-workers,5,15 were positive

experiences and fostered an alliance among the workers.

There was a dichotomy between the joy in taking care

of people and the poor teamwork among the medical

people managing the situation during an earthquake in

237

Iran.16 The lack of trained leadership made the coordination of the workers, especially from other countries, very

difficult. This resulted in ineffective outcomes for the

patients. Communication of a clear and simple plan was

paramount to the survival of victims.24 This communication entailed not only the relationship between the

workers, but also addressing the gaps in nursing education

regarding emergency response, building a relationship

between government organizations and hospital administrators to ensure seamless care after a disaster, and

improving the infrastructure within the hospital system to

address team training and responsiveness.16,18,24 Research

following the tsunami in Thailand illustrated a wellorganized procedure for handling the treatment and

evacuation of victims from a small rural area.24 The case

study suggested that the success of this relief effort was

attributed to the effective communication from the

medical director, the efficient use of volunteers as they

appeared on the scene to help, and the coordination of

scarce resources in treating the patients.

The intervention of team building was found to consist

of the relationship workers held with their peers and

leaders, and the ability to deliver care to the victims in a

coordinated fashion (see Fig. 1). Fostering alliances and

coordinating with co-workers resulted in the seamless

delivery of care, and factored into the concept of team

training as an important intervention in relief work.

Preparation as an intervention

The concept of preparing not only relief workers but also

organizations for the unplanned emergency situation was

found to positively impact the response of workers. The

commitment of the organization to assure support to staff

during a time of social unrest and panic with a clear chain

of command was considered by workers to be extremely

important in reducing stress levels.10,1618 Staff reported a

high level of anxiety in not knowing what the potential

danger could be to themselves and their families, yet they

professed a sense of commitment to care for and protect

the patients during a crisis.10,1618

Clinical skill development and the ability to function at

a high level of expertise reduced workers feelings of

anxiety, fear and anticipation.11,18 Formal education in

trauma and disaster management in nursing school

curriculums, development of preplanned protocols and

ongoing inservice training to prepare nurses for the

demands of caring for disaster victims were reported in

several studies.17,18,24,25 Miller noted the importance of

2009 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

238

DS Walsh

culturally appropriate training and support programmes

in a study post-tsunami in Sri Lanka.25 Workers were

involved in overseeing support groups for the survivors of

the tsunami. Preplanning for worker/client response is

paramount for the success of any relief activity. Communities embraced the concept of support groups, but the

impact could have been greater had the planning focused

on local cultural beliefs and less on utilizing Western

suppositions.

Workers reported a definite fear of abandonment, both

by their institution and governments.17,18 It is important to

realize that the staff who are prepared for the unplanned

emergency can be as stressed as the first responder.

Although hospitals had readiness plans in place, the staff

did not perceive the institutions as having the ability to

sustain them during a disaster, lacking the infrastructure

to support staff during any crisis situation. The role of the

charge nurse was identified as crucial to the success of the

staff. Specific leadership training should be directed to

those in the role of charge nurse.17,18

The individual themes that were found to be the framework of the intervention of preparation included the

importance of training, development of protocols and

institutional support as evidenced by staff clinical readiness. Integrating these themes resulted in the major concepts involving the importance of a functioning chain of

command, need for formal education in leadership training, and institutional support to staff to reduce the anxiety

of the work expected of them under trying conditions

(see Fig. 1).

DISCUSSION

Synthesis of results

Disaster relief poses not only physical but also psychosocial danger to participants. Empirical research has examined the effect on workers and reported a marked increase

in PTSD, depression and stress disorders. These responses

were exhibited in sleeping, eating and drinking disorders,

feelings of frustration and sadness, and inadequacy. One

cannot focus only on the detrimental effects of assisting in

relief efforts. From these experiences workers were able

to empower individuals to help themselves through teaching, feel the joy in helping others, and realize a deep

commitment and compelling need to respond. This altruism and dedication was a guiding force in keeping workers

motivated when conditions were at times difficult.

Debriefing is a mechanism that enables workers to elicit

the feelings and responses that result from the experience.

2009 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

It offers a supportive network for workers to reconstruct

their experiences and verbalize their thoughts and feelings

and reduce the impact on their lives.

Decreasing the psychosocial effects of relief work

centres around the importance of adequately training

relief workers prior to undertaking an assignment. This

should include the development of curricula for education

and training in disaster preparedness, triage systems,

teamwork and adjustment to the scope of devastation that

can result from a humanitarian crisis. Workers must form

a cohesive team that is in control of the environment and

cognizant of team skills and hierarchy of command. There

should exist a level of confidence within the organizational

infrastructure that staff will have sufficient supplies to

support their efforts. Maintaining control with open communication is key to the success of any relief project.

For workers to react effectively there should be clear

and concise disaster plans further underscoring the importance of preparing for a disaster. The development

of a documented chain of command, training and safety

protocols, exit strategies, location and procurement of

supplies and the process for mobilizing, inter-agency

agreements, volunteer and governmental relations, and a

national policy for disaster response will contribute to

providing for future safety of workers.

Based on the results of this review there is a gap in the

education of the volunteer and professional responders to

disaster situations. Trauma training and disaster management should not only be included in the curriculum of

nursing, medical school and professional responder

courses, but in volunteer organization orientation

programmes. Ongoing disaster training in hospitals and

governmental agencies should be a mandatory competency to assure that clinical skill level, as well as organizational and management skills, are maintained at a high

level of responsiveness.

The relationship between government agencies and

health-care institutions must assure a seamless plan of care

for victims, and supportive services for the staff. The

development of clear and simple disaster plans using the

tenets of team training is necessary for an organized

response to a crisis. The staff should be assured that they

will have the full support of the organization at a time of

social unrest. The availability of psychosocial support

services post disaster has been shown to decrease the

negative effects of relief work.

Communication is the commonality throughout the

process of disaster relief. It is key in preparing for a crisis,

Reducing Psychosocial Disturbances

maintaining availability of support and supplies required

to care for patients during the situation, and assuring that

relief workers are cared for physically and psychologically

post crisis.

In the wake of the terrorist attack on the Twin Towers

in New York City on 11 September 2001, there has been

an emphasis on research regarding disaster relief and the

effect on workers both physically and psychologically.

Dionne reviewed the support systems provided by the

Emergency Medical System in New York following 911,

and through the voice of the responders discovered the

inadequacy of the support systems.26 Inconsistent critical

incident debriefing, lack of counselling support systems,

and punitive responses to behavioural issues were

reported by members of an emergency system recognized

as a leader in disaster training with the availability of the

best resources in the country.26

CONCLUSION

In summary, it is suggested that because of the high level

of PTSD reported post disaster work, it is imperative that

governmental and non-governmental agencies consider

the psychological consequences and costs of rescue

work.

Predisaster training, evaluation and teaching of volunteers, as well as ongoing support post disaster might

reduce the frequency or severity of developing PTSD.

Organizations with the mission to participate during

humanitarian crises should continue to research the experiences of workers. Proper education and training regarding working with teams, multicultural immersion prior to

leaving for a humanitarian mission, combined with a

support network upon return, will optimize the performance of the workers, as well as ease re-entry into their

lives at home.

Implications for practice

Relief workers and humanitarian volunteers will continue

to face the challenge of caring for people in the most

extreme circumstances. It is the responsibility of the professions of nursing, emergency care and medicine, and

those humanitairian organizations that have taken on the

role of responding to these situations to properly prepare

and subsequently care for their members. Formal education and clinical readiness and support, specific curricula

in disaster management, training in teamwork and proper

239

utilization of volunteers and a social support framework

have been shown to have an effect on the development of

PTSD.

Further research is warranted on this topic to continue

to determine the long-term effects on workers of witnessing the devastation of a natural disaster. The integrated

review is a method that synthesizes diverse sources into a

holistic understanding of a particular event.7 Disaster

research pertains to all cultures, all circumstances and the

key concepts should continue to be identified to assist in

caring for those workers and expanding the knowledge

base to further delineate cultural differences.

It would be helpful to expand the research to include

indirect or vicarious trauma as reported by those who

support the victims of relief work. Vicarious trauma is the

result of cumulative exposure exposed to the trauma

stories from others, not experiencing the trauma oneself.

Clark and Gioro (1998) researched nurses and indirect

trauma and reported that the steps for prevention of

developing chronic and long-term PTSD included

acknowledging that it can occur, connecting and talking

with other nurses.27 These findings concur with the findings of this review. Humanitarian aid and disaster relief

organizations have recognized vicarious trauma as one of

the more serious occupation hazards experienced by their

staff, both in the field and in the home office.28 Healthcare and humanitarian organizations should take a proactive approach to providing assistance and, through further

research, analyse its effects in order to lessen its impact on

those who assist in humanitarian relief work.

REFERENCES

1 World Health Organization. Tsunami Situation Reports.

Available from URL: http://www.who.int/hac/crises/

international/asia_tsunami/sitrep/en/. Accessed 2006.

2 Mail and Guardian. Disaster Rescuers at Risk of Post-traumatic

Stress. Available from URL: http://www.mg.co.za/

articlepage.aspx?area=/insight/insight_international&

articleid=195026. Accessed 2006.

3 Drydan P. When Nothing is Left: Disaster Nursing after the

Tsunami. Available from URL: http://www.medscape.

com/viewarticle/501567. Accessed 2005.

4 Bortolotti D. Hope in Hell. Inside the World of Doctors without

Borders. Buffalo, NY, USA: Firefly Books, 2004.

5 Brandt G, Fullerton C, Saltzgaber L, Ursano R, Holloway

H. Disasters: Psychological responses in health care providers and rescue workers. Nord Journal of Psychiatry 1995; 49:

8994.

6 Norris F. Psychosocial Consequences of Natural Disasters in

Developing Countries: What Does Past Research tell us about the

2009 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

240

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

DS Walsh

Potential Effects of the 2004 Tsunami? United States Department of Veteran Affairs National Center for PTSD.

Available from URL: http://www.ncptsd.va.gov/facts/

disasters/fs_tsunami_research.html. Accessed 2006.

Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: Updated

methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2005; 52: 546

553.

Cooper H. Scientific guidelines for conducting integrative

research reviews. Review of Educational Research 1982; 52:

291302.

Jackson G. Methods for integrative reviews. Review of

Educational Research 1980; 50 (3): 438460.

Berah E, Jones H, Valent P. Experience of a mental health

team involved in the early phase of a disaster. Australian and

New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 1984; 18: 354358.

Fullerton C, McCarroll J, Ursano R, Wright K. Psychological responses of rescue workers: Fire fighters and trauma.

American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 1992; 62: 371378.

McFarlane A. Phenomenology of posttraumatic stress

disorders following a natural disaster. Journal of Nervous

and Mental Disease 1988; 176: 2229.

Fullerton C, Ursano R, Wang L. Acute stress disorder,

posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in disaster or

rescue workers. American Journal of Psychiatry 2004; 161:

13701376.

Guo Y, Chen C, Lu M, Tan H, Lee HW, Wang TN.

Posttraumatic stress disorder and non-professional rescuers

involved in an earthquake in Taiwan. Science Direct 2004;

127: 3541.

Armagan E, Engindeniz Z, Devay A, Bulent E, Ozcakir A.

Frequency of post-traumatic stress disorder among relief

force workers after the tsunami in Asia: Do rescuers

become victims? Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 2006; 21:

168172.

Nasrabadi A, Naji H, Mirzabeigi G, Dadbakhs M.

Earthquake relief: Iranian nurses responses in Bam, 2003,

and lessons learned. International Nursing Review 2007;

54: 1318.

2009 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

17 OBoyle C, Robertson C, Secor-Turner M. Nurses belief

about public health emergenciesfear of abandonment.

American Journal of Infection Control 2006; 34: 351

357.

18 Riba S, Reches H. When terror is routine: How Israeli

nurses cope with multi-casualty terror. Online Journal

of Issues in Nursing 2002; 7: Manuscript 5. Available

from URL: http://www.nursingworld.org/ojin/topic19/

tpc19_5.htm. Accessed 2006.

19 Breslau N, Peterson E, Kessler R, Schultz L. DSM PTSD

IV Scale. American Journal of Psychiatry 1999; 156: 908

911.

20 Zung W. Zung Self Rating Depression Scale. Archives of

General Psychiatry 1965; 12: 6370.

21 Blake D, Weathers F, Nagy L, Kaloupek D, Charney D,

Keane T. Development of a clinician-administered PTSD

Scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress 1995; 8: 7590.

22 Chen C, Lin S, Tang H, Shen W, Lu M. Chinese version of

the Davidson Trauma Scale. Psychiatry Clinical Neuroscience

Journal 2001; 5: 493499.

23 Meltzer-Brody S, Churchill E, Davidson J. Derivation of the

SPANa brief diagnostic screening test for post-traumatic

stress disorder. Psychiatry Research 1999; 88: 6370.

24 Ammartyothin S, Ashkensai I, Schwartz D et al. Medical

response of a physician and two nurses to the mass-casualty

event resulting in the Phi Phi Islands from the tsunami.

Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 2006; 21: 212214.

25 Miller J. Waves amidst war: Intercultural challenges while

training volunteers to respond to the psychosocial needs of

Sri Lankan tsunami survivors. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention 2006; 6: 349365.

26 Dionne L. After the fall: 911s effects on New Yorks EMS.

Journal of Emergency Medical Services 2002; Nov: 27 (11): 16.

27 Clark M, Gioro S. Nurses, indirect trauma and prevention.

Journal of Nursing Scholarship 1998; 30 (1): 8587.

28 Headington Institute. Humanitarian Aid and Disaster Relief

Personnel. Available from URL: http://www.headingtoninsititue.org. Accessed 2008.

You might also like

- Obstetrics Perfusion Issues Student-2Document30 pagesObstetrics Perfusion Issues Student-2Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Obstetrics Perfusion Issues Student-2Document30 pagesObstetrics Perfusion Issues Student-2Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Obstetrics Perfusion Issues Student-2Document30 pagesObstetrics Perfusion Issues Student-2Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Self-Assessed Emergency Readiness and Training Needs of Nurses in Rural TexasDocument9 pagesSelf-Assessed Emergency Readiness and Training Needs of Nurses in Rural TexasJbl2328No ratings yet

- Rebmann, 2010Document11 pagesRebmann, 2010Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Obstetric ComplicationsDocument36 pagesObstetric ComplicationsJbl2328100% (1)

- Neonatal Infections 2Document8 pagesNeonatal Infections 2Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Considine, 2009Document17 pagesConsidine, 2009Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Neonatal Infections 2Document8 pagesNeonatal Infections 2Jbl2328No ratings yet

- An Integrative Review: High-Fidelity Patient Simulation in Nursing EducationDocument5 pagesAn Integrative Review: High-Fidelity Patient Simulation in Nursing EducationJbl2328No ratings yet

- Nurses' Preparedness and Perceived Competence in Managing DisastersDocument8 pagesNurses' Preparedness and Perceived Competence in Managing DisastersJbl2328No ratings yet

- Lafauci, 2011Document8 pagesLafauci, 2011Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Obstetric ComplicationsDocument36 pagesObstetric ComplicationsJbl2328100% (1)

- Walsh, 2009Document11 pagesWalsh, 2009Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Israeli Nurses' Intention To Report For Work in An Emergency or DisasterDocument11 pagesIsraeli Nurses' Intention To Report For Work in An Emergency or DisasterJbl2328No ratings yet

- Neonatal Infections - PPTX 9Document10 pagesNeonatal Infections - PPTX 9Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Level of Preparedness For Disaster Response: Nursing Students'Document5 pagesLevel of Preparedness For Disaster Response: Nursing Students'francesjoyginesNo ratings yet

- An Integrative Review: High-Fidelity Patient Simulation in Nursing EducationDocument5 pagesAn Integrative Review: High-Fidelity Patient Simulation in Nursing EducationJbl2328No ratings yet

- Neonatal Infections - PPTX 9Document10 pagesNeonatal Infections - PPTX 9Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Whitty, 2009Document6 pagesWhitty, 2009Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Disaster and Emergency Nursing Learning PlanDocument1 pageDisaster and Emergency Nursing Learning PlanJbl2328No ratings yet

- An Integrative Review: High-Fidelity Patient Simulation in Nursing EducationDocument5 pagesAn Integrative Review: High-Fidelity Patient Simulation in Nursing EducationJbl2328No ratings yet

- Neonatal Infections 3Document15 pagesNeonatal Infections 3Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Neonatal Infections - PPTX 9Document10 pagesNeonatal Infections - PPTX 9Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Neonatal Infections - PPTX 9Document10 pagesNeonatal Infections - PPTX 9Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Neonatal Infections - PPTX 9Document10 pagesNeonatal Infections - PPTX 9Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Neonatal Infections - PPTX 9Document10 pagesNeonatal Infections - PPTX 9Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Neonatal Infections - PPTX 9Document10 pagesNeonatal Infections - PPTX 9Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Neonatal Infections - PPTX 9Document10 pagesNeonatal Infections - PPTX 9Jbl2328No ratings yet

- Neonatal Infections - PPTX 9Document10 pagesNeonatal Infections - PPTX 9Jbl2328No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Escalado / PLC - 1 (CPU 1214C AC/DC/Rly) / Program BlocksDocument2 pagesEscalado / PLC - 1 (CPU 1214C AC/DC/Rly) / Program BlocksSegundo Angel Vasquez HuamanNo ratings yet

- AWS S3 Interview QuestionsDocument4 pagesAWS S3 Interview QuestionsHarsha KasireddyNo ratings yet

- 3 - 6consctructing Probability Distributions CG A - 4 - 6 Lesson 2Document24 pages3 - 6consctructing Probability Distributions CG A - 4 - 6 Lesson 2CHARLYN JOY SUMALINOGNo ratings yet

- Lorain Schools CEO Finalist Lloyd MartinDocument14 pagesLorain Schools CEO Finalist Lloyd MartinThe Morning JournalNo ratings yet

- Media LiteracyDocument33 pagesMedia LiteracyDo KyungsooNo ratings yet

- Description MicroscopeDocument4 pagesDescription MicroscopeRanma SaotomeNo ratings yet

- Vsip - Info - Ga16de Ecu Pinout PDF FreeDocument4 pagesVsip - Info - Ga16de Ecu Pinout PDF FreeCameron VeldmanNo ratings yet

- Resume Android Developer Format1Document3 pagesResume Android Developer Format1Shah MizanNo ratings yet

- LAU Paleoart Workbook - 2023Document16 pagesLAU Paleoart Workbook - 2023samuelaguilar990No ratings yet

- RRR Media Kit April 2018Document12 pagesRRR Media Kit April 2018SilasNo ratings yet

- 360 PathwaysDocument4 pages360 PathwaysAlberto StrusbergNo ratings yet

- Linear Programming Models: Graphical and Computer MethodsDocument91 pagesLinear Programming Models: Graphical and Computer MethodsFaith Reyna TanNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Disciple Making PaperDocument5 pagesPhilosophy of Disciple Making Paperapi-665038631No ratings yet

- Classification of MatterDocument2 pagesClassification of Matterapi-280247238No ratings yet

- CELTA Pre-Interview Grammar, Vocabulary and Pronunciation ExercisesDocument4 pagesCELTA Pre-Interview Grammar, Vocabulary and Pronunciation ExercisesMichelJorge100% (2)

- Solution Aid-Chapter 01Document21 pagesSolution Aid-Chapter 01Vishal ChintapalliNo ratings yet

- Mitosis Quiz: Answers Each Question. Write The Answer On The Sheet ProvidedDocument5 pagesMitosis Quiz: Answers Each Question. Write The Answer On The Sheet ProvidedJohn Osborne100% (1)

- Otis Brochure Gen2life 191001-BELGIUM SmallDocument20 pagesOtis Brochure Gen2life 191001-BELGIUM SmallveersainikNo ratings yet

- MARCOMDocument35 pagesMARCOMDrei SalNo ratings yet

- Tos IcuDocument1 pageTos IcuMary Cris RombaoaNo ratings yet

- Monetary System 1Document6 pagesMonetary System 1priyankabgNo ratings yet

- Joy Difuntorum-Ramirez CVDocument2 pagesJoy Difuntorum-Ramirez CVJojoi N JecahNo ratings yet

- LP IV Lab Zdvzmanual Sem II fbsccAY 2019-20z 20-ConvxvzzertedDocument96 pagesLP IV Lab Zdvzmanual Sem II fbsccAY 2019-20z 20-ConvxvzzertedVikas GuptaNo ratings yet

- MATH Concepts PDFDocument2 pagesMATH Concepts PDFs bNo ratings yet

- All Types of Switch CommandsDocument11 pagesAll Types of Switch CommandsKunal SahooNo ratings yet

- Differentiation SS2Document88 pagesDifferentiation SS2merezemenike272No ratings yet

- Helmholtz DecompositionDocument4 pagesHelmholtz DecompositionSebastián Felipe Mantilla SerranoNo ratings yet

- Morpho Full Fix 2Document9 pagesMorpho Full Fix 2Dayu AnaNo ratings yet

- 341SAM Ethical Leadership - Alibaba FinalDocument16 pages341SAM Ethical Leadership - Alibaba FinalPhoebe CaoNo ratings yet

- MATH6113 - PPT5 - W5 - R0 - Applications of IntegralsDocument58 pagesMATH6113 - PPT5 - W5 - R0 - Applications of IntegralsYudho KusumoNo ratings yet