Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Telephonic Conversation - Arabic

Uploaded by

farshan296015Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Telephonic Conversation - Arabic

Uploaded by

farshan296015Copyright:

Available Formats

The How are you?

sequence in telephone openings in

Arabic

Eman Saadah

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

esaadah2@illinois.edu

This paper reports on one particular speech activity, viz. telephone

openings, to conduct a cross-cultural comparison of how Arabs

perform the ritual routines of the How are you? sequence. Using

conversation analysis (CA) as a methodology, this qualitative

study is based on data collected from natural interaction between

Arabs. In Arabic, the How are you? sequence is canonically

scripted to function as an inquiry about the well-being and latest

news of the recipient of the call as well as his/her other immediate

family members. However, these telephone openings are expanded

to show differences in norms of behavior from the ones reported in

the literature to mark cultural identity that is unique to this speech

community.

1. Introduction

In this study, I will focus on the behavior of Arabic speakers in telephone

conversation openings when they call relatives and family members. As a

community that is claimed to have strong social ties among its members

(Ahlawat & Zaghal 1989), Arabic speakers are expected to exhibit

differences in telephone behavioral patterns from communities that are

characterized differently. In order to check for such a difference, the How

are you? sequence is investigated to exemplify how interactants help

maintain intimacy among themselves by extending parts of the telephone

conversation as a means of showing care and love for each other.

Difference in the norms of interaction over the phone in general, and

within the How are you? sequence in particular, has been investigated in

previous studies. Since Schegloffs (1968) study on the organization of

conversation and later on telephone conversation openings (Schegloff

1979), the study of telephone openings has attracted a lot of attention in

the field (Schegloff & Sacks 1973; Schegloff 1979; Lindstrm 1994;

Houtkoop-Steenstra 1991; Taleghani-Nikazm 2002).

I hypothesize that the extended How are you? sequence occurring after

the summons-answer sequence in Arabic serves an important function

Studies in the Linguistic Sciences: Illinois Working Papers 2009: 171-186

Copyright 2009 Eman Saadah

STUDIES IN THE LINGUISTIC SCIENCES 2009

between interlocutors. It is routinely structured in telephone conversations

among close relatives and friends and seems to be obligatory in informal

interactions between such participants. The absence this sequence or the

provision of a shortened version of this sequence makes the interaction

rigid and impolite which gives the impression that the caller is not friendly

and sociable.

2. Telephone openings and literature review

Schegloff (1979) found that most U.S. telephone openings include an

identification and recognition sequence. In addition, he identified four

sequences of adjacency pairs in mundane private telephone conversation

openings:

1. a summons-answer sequence (e.g. the phone rings and the callee

answers Hello);

2. an identification and/or recognition sequence (e.g. Bill!/Hey

Sally);

3. a greeting sequence (e.g. Hi/Hi);

4. a How are you sequence (e.g. How are you?/good, how

about you?) (Schegloff, 1986).

That telephone openings are found to differ in varying cultures is a wellestablished fact. Despite the occurrence of the How are you? sequence in

telephone conversation in all targeted speech communities, it has been

shown that the extent and pattern vary from one culture to the other, e.g.

Dutch (Houtkoop-Steenstra 1991), Finnish (Halmari 1993), Swedish

(Lindstrm 1994), German (Pavlidou 1994), Greek (Sifianou 2002), and

Chinese (Sun 2004).

Halmari (1993) studies, among other things, the How are you? sequence

in business telephone conversations in two different languages: Finnish

and American English. For Finnish speakers, when the How are you?

sequence is initiated, it elicits a lengthy non-topical sequence, i.e., it is

understood as question that requires an elaborate answer. However, for

American English speakers, the How are you? sequence in business

telephone conversations is usually restricted and has the illocutionary

function of a greeting and thus requires a short answer of Im fine or

good.

In another study, Pavlidou (1994) reports on Greek and German

conversational styles, focusing on politeness in telephone calls.

Investigating the How are you? sequence, the researcher finds different

172

SAADAH: THE HOW ARE YOU? SEQUENCE IN ARABIC

norms between the two cultures. She concludes that Greeks emphasize the

relationship aspect of communication by using more phatic utterances,

while Germans tend to focus more on the content of the conversation, are

more direct, and use less phatic utterances.

Many studies claim that the How are you? sequencewhich is part of

the opening sequence of telephone conversationsis also an instance of

phatic communion. Phatic communion is a term that is attributed to

Malinowski (1923) and affiliated with anthropology, and has been

borrowed into various fields (e.g. semantics, sociolinguistics, conversation

analysis, and communication). Phatic communion, according to

Malinowski, refers to a type of speech people get involved in aimlessly to

create ties of union which merely fulfills a social function. This term has

been also used to describe responses to the inquiry How are you? in

telephone conversation. For example, Coupland, Coupland, & Robinson

(1992) identify a range of strategies elderly people use to achieve degrees

of phaticity when they respond to a scripted How are you? question in

interviews about health-related issues.

Sun (2004) discusses the common expression about well-being, How are

you?, between female participants in Chinese. The researcher focuses on

studying phatic talk in terms of deictic reference. While involved in small

talks, a Chinese speaker might choose to replace the second person deictic

pronoun you with other terms such as mother if one of the participants

in the telephone conversation is the mother of the other. This verbal

behavior between interlocutors shows deference, awareness of social

status, and politeness, especially when addressing seniors. Some

interlocutors might choose to drop the pronoun, using a pro-drop form,

and add adverbials following or preceding the main component, e.g.

doing well lately. Sun claims that in interpersonal calls, the inquiry

How are you? has dual functions: a statement of purpose when it is

preceded by comments such as Long time no see/calling and a phatic

communion.

Generally, the How are you? sequence in Arabic telephone conversation

is characterized by lengthy and detailed turns among interactants.

However, this extended and elaborate version depends on several factors.

First, it depends on the type of relationship between interactants. Unlike

distant relationships, among close relatives and friends a detailed version

of this sequence is always expected. Second, gender of the participants is

an important factor that mandates the nature of this sequence. Female

callers tend to personalize this sequence and ask mainly about ones,

partners, childrens, and other immediate family members well being.

This can be extended to inquire about recent events or latest news

173

STUDIES IN THE LINGUISTIC SCIENCES 2009

regarding this particular person or any of his immediate family members.

On the other hand, though male callers ask about the well being of the

other interactant, his/her spouse, and children, the inquiry is different in

nature. This sequence is more routinized and fulfills the function of mere

asking and not necessarily eliciting genuine responses from the other

caller. Third, the nature of this sequence depends on the reason for the

call, whether formal or informal. Formal reasons include the caller asking

about specific information or extending an invitation to the callee, while

informal reasons include situations when interactants call each other to

chat with no particular purpose. Of course, unlike in informal calls, in

which the purpose for the call is to keep in touch, formal calls are

characterized by shortened How are you? sequences in which the caller

gets to the reason behind calling the other shortly after the call starts. In

other cases, we find overlap between these factors which renders a

differently structured sequence than what is expected. For example, even

when participants call each other for a specific reason such as to extend

invitation to a party, they might get involved in an extended How are

you? sequence. This is indicative of a more polite and respectful

interaction which is not uncommon between members of the Arabic

speech community.

3. The How are you? sequence in Arabic

Based on the data collected for this study, the How are you? sequence in

telephone conversation in Arabic has a dual function: general and specific.

The sequence has a general function in that it might include several

inquiries within an interaction. The turns are normally expanded to ask

about the well-being of the callee, his/her news, and finally wishing

him/her that everything would be fine at their side. These questions in

most cases require a formulaic response, e.g. alhamudulellaah, thanks to

God. On the other hand, the How are you? sequence has also a specific

function. This sequence can be condensed in nature in that it incorporates

all these in one turn. Depending on purpose for the call and on the callees

response, this sequence can lead to the initiation of the first topic.

As the data below show, the How are you? sequence in Arabic telephone

conversations can be expressed in more than one turn. Native speakers

typically believe that the first time serves the function of breaking the ice

and sensing from the callees voice and response if this is a good time to

proceed with the call. Such an inquiry has a routinized response even if

there are recent news or events that need to be revealed. This response

which typically denotes ones well-being and thanking God for the present

state of affairs is shared by all Arab community members and is obliged

174

SAADAH: THE HOW ARE YOU? SEQUENCE IN ARABIC

by religious beliefs. Therefore, this structured reply has cultural and

religious roots which result in this conventionalized response. Normally,

the second part of the How are you? sequence is almost identical to the

previous one but with more inquiries to include, among other issues,

asking about physical well-being, latest news, and inquiries about the

addressees children. It is also routinely followed by a typical rejoinder

that expresses the callers wish for everything and everyone to be good at

the other participants side.

4. The data

The sample consists of 10 audio-taped telephone calls in Arabic that were

made by 5 native Arabic speakers and recorded by the researcher. All calls

were made by middle-class Arabs who ranged in age between 32 and 65.

They included conversations between family members. The phone calls

were all either initiated or received to the researchers residence and all

involved persons she personally knows.

In this paper, I present descriptions, analysis, and interpretations of the

How are you? sequence in informal Arabic telephone conversations

between family members. Specifically, naturally occurring telephone

conversations were analyzed to identify how the moves within the How

are you? sequence are conducted in Arabic. Selected telephone calls were

transcribed according to the transcription notation put forth by Jefferson

(1984: ix-xvi). In the following examples, the top line is the talk in the

native language while a literal translation appears in the second line. The

third line represents the translation of talk in idiomatic English.

(1)

01

02

03

04

05

06

[[Phone rings.]]

Amjad:

allo.

Hello.

Kamal:

assalaamu laykum.

peace upon you-PL.

Peace be upon you.

(0.9)

Amjad:

alaykum essalaa::m wa ramatullaah,

upon you-PL peace and mercy-god,

Peace be upon you too and gods mercy,

AHLEin abu-lbaraa=

WELCOme father-albaraa [males name]=

WELCOme father of Albaraa-

175

STUDIES IN THE LINGUISTIC SCIENCES 2009

07

Kamal:

08

09

10

Amjad:

11

Kamal:

12

13

14

15

Amjad:

16

Kamal:

=abumeid chef alash shu akhbarak

[name-diminutive] how well-being what news-your

[name-diminutive] How are you what is your news

inshaallah tamaam.

willing god fine.

Gods willing, fine

(0.4)

lamdulellaah allah ybaarik feek (0.1) tama[am,

thanks god

god bless you

(0.1) fi[ne,

Thanks to god may god bless you (0.1) Im fine

[cheef

how

Setak cheef omorak cheef zghaarak.

health-your how news-your how little ones-your.

is your health what is your news how are your

children.

inshaallah mneeen.

willing god good-they.

Gods willing they are good.

(0.9)

walla lamdulellaah tamaam allah <yb[aarik feek>

God

thanks god fine

god <bl[ess you>

Swearing By God, thanks to God fine may God

bless you

[lamdulellah

[thanks god

Thanks to God

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Amjad:

alla yeTeekel aafye inshaallah

god give you health willing god

May God give you health by Gods willing

(0.2)

>walla abbeina nsallem ala ammi neTTamman

>by god like-we say hello to uncle-my check-we

By god we like to say hello to my uncle and check

ale: inshaalla awaleik .<

on him willing god around you.<

on him gods willing is he around you

(1.7)

hayyo mawjood

here-he available

Here, he is available

(0.3)

176

SAADAH: THE HOW ARE YOU? SEQUENCE IN ARABIC

24

25

26

Kamal:

<tfaDDal>.

please.

(0.2)

alla:(h) ykhalleek.

god

bless-you.

May God bless you.

This exchange occurs between two male family members. Kamal, 42 years

old, called his younger brother-in-law, Amjad, 35 years old, to say hello

to his father-in-law. The father-in-law was visiting Kamal and left to his

son Amjads house in another city. Though Kamal and Amjad have a

close relationship, they have not called each other for some time, that is,

during all that time the father-in-law stayed at Kamals house, a few

weeks.

Example 1 starts with the typical summons-answer and greeting

sequences. As we can see, Arabs, like many other cultures, regard the

ringing of the telephone to be a summons which is answered typically by

allo, hello in line 2. This response to the summons provides the caller

with resources to identify the callee. In line 3, the first pair part of the

greeting sequence is produced. By uttering the greeting only, this first pair

part has another function, namely, is to identify the caller by providing the

recipient with his voice sample. This is an indication that there is a

preference in Arabic telephone conversation to resort to other-recognition

over self-identification. However, in other cultures, self-identification

seems to be the preferred norm in caller and recipient exchanges (cf.

Jorden and Noda, 1987, Park, 2002). The second pair part comes after a

long silence. This might be justified by the fact that both participants did

not call each other for some time, so it took the recipient some time to

recognize the identity of the caller. However, in the reply, the greeting is

uttered with more emphasis than the surrounding talk and includes

recognition of the caller, (line 6), which indicates the callee has identified

the caller through his voice. Amjad identifies the caller by a specific

address term that is widely used by Arabic community members, abulbaraa, literally father of Baraa (Baraa is a male name in Arabic). This

address term is commonly used by a younger person when addressing an

older one. Using abu + the name of eldest male son of the caller is

considered more formal and respectful than addressing with ones first

name, but not as formal as addressing with Mr. or Drcommonly used

when a member has a doctorate degree. Amjads choice of this address

term shows his awareness of the age difference and preference to use a

somewhat formal term which indicates politeness.

177

STUDIES IN THE LINGUISTIC SCIENCES 2009

As soon as Amjad identifies Kamal and greets him (lines 5 and 6), Kamal

produces the next turn in latched position. Within this very short

interaction between the two males we find two overlaps by Kamal with

Amjads turns. In line 10, there is an overlap when Amjad replies to

Kamal and just before he is about to start another topic. Kamals overlap

with Amjads turn results in the termination of Amjads turn and the start

of Kamals. Kamal assumes the role of talk organizer and initiator and this

is expected since he is the one who initiated this telephone call. The

second overlap occurs in line 15 and again results in the termination of

Amjads turn. In line 7, at the beginning of the first pair part of the How

are you? sequence, Kamal produces a diminutive address term which is

indicative of love, affection, and a strong relation between the two

participants. This is similar to nicknames people usually assign to their

children. Also, the use of this address term in this interaction also

highlights the age difference between the interlocutors.

After performing two typical sets of the How are you? sequence, Kamal

proceeds by introducing the purpose for the call, viz. checking if his

father-in-law is available to talk to him (line 19). Although Kamal

ultimately makes a switchboard request, we can see that he went through

the How are you? sequence with the person who answered the phone in

which he asks about the answerers well-being, news and family.

(2)

01

Qasem:

02

03

Kamal:

04

05

06

07

Qasem:

08

Kamal:

essalaamu alaykum,

Peace upon-you

Peace be upon you

(0.1)

^aywa ammi

yes my uncle

(0.1)

essalamu alakum cheef halak shu akhbarak.

peace upon-you how you what news-your.

Peace be upon you how are you what are your

news.

(0.5)

allahi yaeek allah ysalma[k (0.1) keGod welcome-you god bless [you(0.1) hoMay God welcome you God bless you ho-

[cheef Setak=

[how health-your.=

How is your health.

178

SAADAH: THE HOW ARE YOU? SEQUENCE IN ARABIC

09

Qasem:

10

Kamal:

=inshallah Taybeen. =

=willing god good-all.=

Gods willing you are all fine.

=shteknaalako. =

=miss-you-all.=

We miss you all.

Example 2 is taken from the same telephone conversation as Example 1

and it is a continuation of the conversation of one of the participants in

Example 1, Kamal, with a new interactant, his father-in-law, Qasem.

Kamal wants to check on his father-in-law who was visiting him and his

family and left to his sons house in a near-by city. Qasems son, Amjad,

and Kamal co-participate at the start of the telephone call, in Example 1,

before Amjad hands the telephone to his father to talk to Kamal. The fact

that Qasem is starting out with a greeting is evidence that he knows who is

on the phone. He starts by greeting Kamal with the typical Arabic Islamic

greeting in line 1, essalaamu alaykum, peace be upon you. Kamal

answers with a marked rise in pitch and stressed address term, ammi, my

uncle. Starting the turn with a markedly higher pitch level and a stressed

address term might indicate excitement and pleasure conversing with this

person. Using this address term at the beginning of a phone call serves two

purposes: it shows that identification/recognition has been achieved

through the voice sample of the recipient of the call. Secondly, this

telephone opening can be characterized as intimate especially as the

address term is suffixed by the possessive pronoun i, my which can

represent love, care, and affection towards this interlocutor. In line 5, we

expect to find the second pair part of the greeting initiated by Qasem in

line 1, but instead of replying to Qasems greeting, Kamal initiates the

greeting himself. This might imply that Kamal, the younger participant in

this interaction, thinks that he should initiate greeting his father-in-law and

not the other way around. So, Kamal provides the first pair part of the

greeting sequence where he should have responded with the second pair

part. Immediately following this, in line 5, he goes on with the How are

you? sequence within the same turn. This includes inquiry about Qasems

well-being and latest news. Qasem does not respond to Kamals inquiries,

rather he reciprocates with another inquiry, in line 9. This shows that these

turns within the How are you? sequence does not elicit a genuine

response from the other participant. Indeed, Kamal proceeds with the

conversation without showing any problem that his inquiries were not

responded to by his father-in-law. Rather, these moves are

conventionalized in turn-taking design within this particular sequence to

signify a routinely structured pattern in telephone conversations between

close friends and family members whose relationships are characterized as

intimate.

179

STUDIES IN THE LINGUISTIC SCIENCES 2009

This ritualized How are you? sequence in Arabic telephone

conversations is commonly replicated by a subsequent turn that is closely

positioned to the former one. This is evident in Kamals overlap with

Qasems turn in line 7 and rephrase of the same inquiry by asking about

the other participants health. In the next turn, Qasem does not respond to

Kamals repeated inquiry about his well-being and news, rather he

reciprocates Kamals How are you? sequence, latches it to his turn, and

asks about the well-being of Kamals family. Likewise, the lack of

response by Kamal to Qasems inquiry indicates that such a sequence is

routinized in telephone conversation and is not necessarily answered by

the other participant. Hopper and Chen (1996) show that in Taiwanese

telephone openings, greeting tokens are not always reciprocated at the

next turn. In other words, it is not topicalized. In the next turn (line 10),

Kamal states the main reason for the call; he and everyone else in his

family miss his father-in-law. It seems that Qasems responses to Kamals

inquiries were not elaborate because he knows Kamals intention behind

the call. Indeed, both participants were practical in quickly wrapping up

the How are you? sequence to proceed to more important matters.

(3)

01

02

03

04

05

06

07

08

09

Layla: >essalamu alayku-<

>peace upon-yo-<

Peace be upon yo-

(0.5)

Nora: <ahlei::n yamma>, wa alaykum essalaa:mu wa

<hello:: my mother>, and upon-you peace and

Hello my mother and peace be upon you too and

ramatullahi wa barakatu=

mercy god and blessings-his=

Gods mercy and blessings

Layla: =kei:f elaa::l.

=how the-well-being.

How are you

(0.2)

keif ento: y:amma?, keif Seetko?,

how you-PL my mother?, how health your-PL?,

How are you mother? How is your health?

(0.4)

Nora: elamdullellah rabbi elalameen keif Se[tik

thanks god god all creation how health[your

Thanks God how is your health, you?

180

SAADAH: THE HOW ARE YOU? SEQUENCE IN ARABIC

10

11

12

13

Layla:

14

15

16

17

Nora:

18

19

Layla:

20

Nora:

21

22

Layla:

23

24

25

Nora:

26

Layla:

27

Nora:

28

Layla:

ENTI?]

YOU?]

YOU?

[(alla yeTeeko) ]

[(god give you-PL) ]

May God give you all

(0.5)

walla tamaa::m. wallalamdulellahhh.

by god fine::. And thanks god

By God Im fine. And thanks to God

(0.17)

kol eshi tamaam.

Every thing fine.

Every thing is fine.

(0.2)

mm A:KEED?

mm SURE?

(0.9)

aa::h wall:a la::hh elamdu:lellaah=

O::h by God no:: thanks to God-

o keif edeike:::?

and how hands-your::?

and how are your hands?

(1.0)

^ LAA zai ma homma bes yani a:ssa akhaff eshwayya

^ NO as

them

but mean feel bit

little

No as before but I feel better a little bit

ensahalla.

willing-god.

by Gods will.

(0.5)

tabe insaalla enshaalla ensh=

alright willing-god willing-god willi=

alright Gods willing Gods willing willi=

[inshaalla

[willing-god

by Gods will-

[alla kareem=

[god generous=

God is generous

inshaalla yamma >inshaalla.<

willing-god my mother >willing-god.<

By Gods willing mother >by Gods will<

181

STUDIES IN THE LINGUISTIC SCIENCES 2009

29

30

31

32

Nora:

33

34

Layla:

35

36

Nora:

37

38

Layla:

39

40

Nora:

41

42

Nora:

43

(0.2)

^laa: asan shwayya assa aali walla.

^no: better little feel myself by god.

No I feel a little better by Gods name.

(0.4)

mmm:::.

mmm:::.

(0.2)

ento?

inshaaallah. keif awalkum

willing-god. how being-you-PL. you-PL?

Gods willing. How is everything with you all?

(0.4)

>haina<

>here-we<

Here we are

(0.2)

(eish?)

(what?)

What?

(1.5)

maashi alna <elamdulella::>.

Okay being-we <thanks go::d>.

Doing fine thanks to God.

(1.2)

E::::H ?

E::::H ?

(1.53)

Example 3 is a portion of a conversational interaction between Layla and

her daughter (Nora) that occurs within the long telephone call from which

examples 1 and 2 were extracted and analyzed. Layla has not been feeling

well lately because she is under medication for treating cancer. This

medication has side effects that affect her health in general thus making

her feel sick all the time. It also causes numbness in her hands and feet.

Kamal, Noras husband initiates this call to greet his father-in-law who

was visiting them and left two days ago. In example 1, Kamal talks to his

brother-in-law, Amjad, and in 2 to his father-in-law, Qasem before he

hands the phone to his wife, Nora, to talk to her mother, Layla.

In Line 1, it is shown that Laylas response is rushed and there is also cutoff in the final word. This can be attributed to Laylas prior knowledge of

the callers identity. Obviously, the identification / recognition sequence is

achieved smoothly. Nora immediately identifies the answerers voice and

182

SAADAH: THE HOW ARE YOU? SEQUENCE IN ARABIC

responds with two greetings and the appropriate address term. The first

greeting indicates welcoming the other participant and includes an address

term, ahlei::n yamma, welcome, my mother. However, the second

greeting is the actual response to the mothers greeting in the first pair

part. Noras response to the greeting, wa alaykum essalaa:mu wa

ramatullahi wa barakatu, and peace be upon you too and Gods mercy

and blessings represents the full and long response to the first pair part of

the greeting in the prior turn. To Muslims and Arabs, this is considered the

best way of reciprocating the greeting in line 1. By Islamic teachings, if a

person is greeted with the greeting essalamu alaykum, peace be upon

you, the other interlocutor has to respond appropriately in the second pair

part.

Responding with two greetings is not uncommon between Arabs as has

been shown in Example 2 by two other interlocutors and represented here

in this new set of data. Noras response immediate response, in line 3, is

low, the sound is stretched, and stressed. This could signal an enthusiastic

and respectful caller who identifies the other party right away and is eager

to be involved with her in this interaction. Using the address term mother

and replying with the complete version of the Islamic greeting which is

considered a relatively long reply to a greeting show that the caller is

respectful and wants to respond with a better greeting than the one she was

greeted with.

Following the greeting sequence, the callee starts with the elaborate and

expanded typical Arabic How are you? sequence. Layla inquires about

the well-being of her daughter. In order to do so, she uses the default

version of How are you? kei:f elaa::l, how is the well-being with no

suffixed pronoun. Using this general form makes the inquiry broader to

include not only the caller but everyone else. This in turn prepares for the

next portion of the turn in which Layla explicitly uses the first person

plural pronoun ento:, you all to include every one at the callees side.

She also extends the first pair part turn to inquire about the health of

everyone by suffixing the second person plural pronoun ko, your to the

noun. In line 9, Nora chooses to reciprocate her mothers inquiry with the

full version where an abbreviated shortened response is normally and

typically used. This long response is followed by a reciprocated inquiry

about the mothers health and is overlapped by the mothers next turn.

Noras inquiry about the mother is very specific in nature in which she

focuses the mothers health (lines 9 and 10). This is evident by suffixing

the noun with the second person possessive pronoun k, your and then

using the second person pronoun enti, you. This shows the callers

intention to include only the mother in her inquiry and not other family

members. By asking only about the mother and her health, the caller

183

STUDIES IN THE LINGUISTIC SCIENCES 2009

constructs a How are you? sequence that does not follow the common

elaborate pattern normally produced by other members in the Arabic

speech community. This could have resulted from the callees overlap

with the callers turn which forced the caller to shorten her turn to give a

chance to the other participant to proceed with hers. It is worth noting that

Nora consumed the normal length of such a turn with her lengthy

greetings reply.

This portion of the How are you? sequence where the caller inquires

about her mothers health is topicalized, (line 9), because of the mothers

health condition. Nora produces other turns that might be considered

rejoinders to the turn where she asks about the mothers health, viz. line

20. The specificity about the mothers health is stressed by asking about

her hands in particular (in line 20). In previous adjacency pairs, the mother

is fully cooperating and provides lengthy responses in her second pair part

turns; that is in lines (13, 15, 19, 22, 23). In these turns, Layla does not

initiate any new topic but addresses her daughters worries and ensures her

that she feels good. The daughters inquiry about the mothers health lasts

for few turnsspecifically, three turnsbefore Nora brings this topic to

an end when Layla assures Nora that she really feels better in her lengthy

turn, (lines 28 and 30), after which Nora brings this to an end.

Example 3 shows that the typical How are you? sequence in intimate

family relations is sometimes topicalized with extended question/answer

adjacency pairs about a specific issue that might be brought up as the

conversation unfolds. Usually, the How are you? sequence is resumed

after that topic has been talked about and both participants feel that it can

be satisfactorily brought to an end. In line 34, the How are you?

sequence is again resumedafter an extended interruption with the

mothers inquiry about the well-being of everyone at her daughters side.

The daughter provides a response which is not typical to such an inquiry.

Her response is rushed, compressed, and abbreviated which prompts the

mother to topicalize such an answer. However, in line 40, Nora states that

she and her family are doing fine before she becomes silent for some time

and then produces some vocalizations after which the mother changes the

subject and proceeds with the conversation. All in all, the daughter does

not contribute a lot to this interaction so far and her tone and answers

indicate worry and concern which is stated clearly in the present How are

you? sequence.

184

SAADAH: THE HOW ARE YOU? SEQUENCE IN ARABIC

5. Summary and concluding remarks

To summarize, the How are you? sequence performed by family

members from the Arabic speech community shows universal as well as

specific patterns. Universal patterns in that like telephone conversation

performed by members from other speech communities, the How are

you? sequence is one main component in the openings of Arabic

telephone conversations. For Arabs, intimate interpersonal relations shape

the nature and design of telephone openings resulting in a distinctive

signature that is considered to be unique and different from other speech

communities. Norms of behavior in telephone openings in Arabic have

also specific cultural patterns in that an expanded how are you? sequence

between Arab family members is a sign of intimacy. This sequence is not

normally topicalized unless there is a reason. In such a case, the sequence

is interrupted momentarily to inquire about that specific issue and

afterwards it is resumed. Telephone openings among family callers tend to

be condensed (in that they consist of several TCUs within a turn), fast, and

expanded (in that they stretch over several turns). Using a conversationanalytic framework, it has been shown that the organizational functions of

such interpersonal communication is undoubtedly culture-specific.

There is a trend that advocates looking for universal tendencies when

analyzing telephone openings; however, cross-cultural exemplars show

that differences in the norms of interaction of this structured activity are

well established. Each telephone conversation is shaped and marked with

a distinctive pattern that is influenced by a particular culture, sex of

interlocutors, their relationships, and the reason for the call.

By conducting this research project, I have expanded the set of languages

and contexts investigated for the purpose of attesting that differences are

in fact present in telephone behavior. By examining such differences, the

focus, next, is not on these differences per se but on the divergent

behaviors that characterize every speech community as unique in and of

itself. This in turn leads to a more inclusive picture of larger cultural

contexts and supports the comparative cultural analysis that academicians

struggle to describe. The aforementionedempirically-grounded

accounts of how the organization of telephone openings is designed in

Arabic are by all means rich resources for language teachers. By exposing

one important speech activity; namely, cultural etiquette of telephone

conversations to language learners, I argue that more details and

culturally-sensitive material are, with no doubt, far and better reaching

tools across the other language and eventually to the minds and hearts of

its users.

185

STUDIES IN THE LINGUISTIC SCIENCES 2009

REFERENCES

Ahlawat, Kapur S. & Ali S. Zaghal. 1989. Nuclear and extended family attitudes of

Jordanian Arabs. In Boh, Katja, Giovanni Sgritta & Marvin B. Sussman (eds.),

Cross-cultural perspectives on families, work, and change. New York: Haworth

Press.

Coupland, Justine., Nikolas Coupland, & Justine Robinson. 1992. How are you?:

Negotiating phatic communion. Language in Society 21, 207-230.

Halmari, Helena. 1993. Intercultural business telephone conversations: a case of Finns vs.

Anglo-Americans. Applied Linguistics 14, 408-430

Hopper, Robert & Chia-Hui Chen. 1996. Languages, cultures, relationships: telephone

openings in Taiwan. Research on Language and Social Interaction 29(4), 291-313.

Houtkoop-Steenstra, Hanneke. 1991. Opening sequences in Dutch telephone

conversations. In Boden, Deidre & Don Zimmerman (eds.), Talk and social

structure. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jefferson, Gail. 1984.Transcription notation. In: Atkinson, John Maxwell & John

Heritage (eds.), Structures of social action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jorden, Eleanor & Mari Noda. 1987. Japanese: The Spoken Language. Yale University

Press.

Lindstrm, Anna. 1994. Identification and recognition in Swedish telephone conversation

openings. Language in Society 23, 231252.

Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1923. The problem of meaning in primitive languages.

Supplement to Ogden, Charles Kay & Ivor Armstrong Richards, The Meaning of

Meaning. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. 146-152.

Park, Yong-yae. 2002. Recognition and identification in Japanese and Korean telephone

conversation openings. In Luke, Kang Kwong & Theodossia-Soula Pavlidou (eds.),

Telephone calls: Unity and diversity in conversational structure across languages and

cultures. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Pavlidou, Theodossia. 1994. Contrasting German-Greek politeness and the consequences.

Journal of Pragmatics 21, 487-511.

Schegloff, Emanuel. 1968. Sequencing in conversational openings. American

Anthropologist 70, 10751095.

Schegloff, Emanuel & Harvey Sacks. 1973. Opening up closings. Semiotica 8(4), 189327.

Schegloff, Emanuel. 1979. Identification and recognition in telephone conversation

openings. In Psathas, George (ed.), Everyday language: Studies in

ethnomethodology. Irvington, New York.

Sifianou, Maria. 2002. On the telephone again! Telephone conversation openings in

Greek. In Luke, Kang Kwong & Theodossia-Soula Pavlidou (eds.), Telephone calls:

Unity and diversity in conversational structure across languages and cultures.

Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Sun, Hao. 2004. Opening moves in informal Chinese telephone conversations. Journal of

Pragmatics 36, 1429-1465.

Taleghani-Nikazm, Carmen. 2002. A conversation analytical study of telephone

conversation openings between native and nonnative speakers. Journal of

Pragmatics 34, 1807-1832.

186

You might also like

- Jean-Felix Lalanne - Veillee 84Document7 pagesJean-Felix Lalanne - Veillee 84Алексей Коваленко100% (1)

- Wildman Dick - Pony BluesDocument3 pagesWildman Dick - Pony BlueswuyanguitarNo ratings yet

- Lili Marlene - Daniele BazzaniDocument6 pagesLili Marlene - Daniele Bazzanihrdirector100% (1)

- (Doc Watson) My Grandfathers Clock Acoustic TAB - NOT PDFDocument5 pages(Doc Watson) My Grandfathers Clock Acoustic TAB - NOT PDFmiromarko100% (1)

- 1587A0C3F8C8DD36B7419C66F6DB3BCDDocument5 pages1587A0C3F8C8DD36B7419C66F6DB3BCDSarah Bennett100% (1)

- Ponto Da Gaita - Tablaturas de GaitaDocument9 pagesPonto Da Gaita - Tablaturas de GaitadugabiNo ratings yet

- The Chrysanthemum Guitar ArrDocument8 pagesThe Chrysanthemum Guitar Arrlisten4758No ratings yet

- Scarborough Fair: PerformanceDocument3 pagesScarborough Fair: PerformancetonisNo ratings yet

- Vincent: Words & Music by Don Mclean 1971Document4 pagesVincent: Words & Music by Don Mclean 1971Eric AppollinaireNo ratings yet

- UrduDocument34 pagesUrduNeeraj_Kishori_7860No ratings yet

- Armenian PhrasesDocument6 pagesArmenian PhrasesRaven SynthxNo ratings yet

- El Padrino GodfatherDocument2 pagesEl Padrino Godfathermudhoney1212No ratings yet

- German-Russian DictionaryDocument801 pagesGerman-Russian DictionaryOktam SapayevNo ratings yet

- DADF#AD - Just A Closer Walk With TheeDocument2 pagesDADF#AD - Just A Closer Walk With TheePeter HeijnenNo ratings yet

- A Grammar of Teiwa by Marian KlamerDocument558 pagesA Grammar of Teiwa by Marian Klamerდავით იაკობიძე100% (1)

- Local Government Financial Statistics England #23-2013Document222 pagesLocal Government Financial Statistics England #23-2013Xavier Endeudado Ariztía FischerNo ratings yet

- لؤلؤة الصباح - Foulabook.com - PDFDocument23 pagesلؤلؤة الصباح - Foulabook.com - PDFalimessaoudiNo ratings yet

- Anorexia NervosaDocument15 pagesAnorexia NervosaJia MacabalangNo ratings yet

- 39 Upward Scales Workouts - Gypsy Jazz Guitar Wiki"Document3 pages39 Upward Scales Workouts - Gypsy Jazz Guitar Wiki"zdravko mureticNo ratings yet

- Mele UkuleleDocument2 pagesMele UkulelejaagoodNo ratings yet

- Tigrinya RomanizationDocument2 pagesTigrinya RomanizationygurseyNo ratings yet

- Misty Comping: Ebmaj7 Bbm7 Eb7 Abmaj7 Abm7 Db7Document3 pagesMisty Comping: Ebmaj7 Bbm7 Eb7 Abmaj7 Abm7 Db7Opherman47No ratings yet

- Colloquial Indonesian - Michael C. EwigDocument42 pagesColloquial Indonesian - Michael C. EwigunfoNo ratings yet

- 28 Diagonal Arpeggios 6 And... Gypsy Jazz Guitar Wiki"Document3 pages28 Diagonal Arpeggios 6 And... Gypsy Jazz Guitar Wiki"zdravko mureticNo ratings yet

- Yuki Matsui-Overtake PDFDocument11 pagesYuki Matsui-Overtake PDFFelipe SalazarNo ratings yet

- 2,000 Most Common Italian WordsDocument30 pages2,000 Most Common Italian WordsDanica VranićNo ratings yet

- Spokenarabicofeg 00 WilluoftDocument488 pagesSpokenarabicofeg 00 WilluoftEdson LacirNo ratings yet

- Day by DayDocument1 pageDay by DayLuis IrunurriNo ratings yet

- Vira de Frielas: Guitarra Portuguesa / Viola de FadoDocument9 pagesVira de Frielas: Guitarra Portuguesa / Viola de FadoMiguel MarquesNo ratings yet

- Bibliography of Amazigh Libyan StudiesDocument5 pagesBibliography of Amazigh Libyan StudiesMazigh BuzakharNo ratings yet

- Machine TransDocument70 pagesMachine TransAlberto Casas RodriguezNo ratings yet

- 6 Julia Florida (Barcarola) : Agustin Barrios Mangore (1885-1944)Document4 pages6 Julia Florida (Barcarola) : Agustin Barrios Mangore (1885-1944)chenchenNo ratings yet

- I Saw Three Ships SHEET MUSIC PACKAGE 2.0Document29 pagesI Saw Three Ships SHEET MUSIC PACKAGE 2.0Anthony MathiasNo ratings yet

- Adapting Traditional Kentucky Thumbpicking Repertoire For The Classical GuitarDocument107 pagesAdapting Traditional Kentucky Thumbpicking Repertoire For The Classical GuitarIggy HesherNo ratings yet

- A Time For UsDocument3 pagesA Time For UsAhmad Syahir Ismail100% (1)

- Moraito - Rocayisa (Tangos) LiveDocument5 pagesMoraito - Rocayisa (Tangos) LiveAlfonso Angel Rodríguez EscuderoNo ratings yet

- Riffle: PerformanceDocument3 pagesRiffle: Performancetonis100% (1)

- Bennett T C - ST Louis TickleDocument12 pagesBennett T C - ST Louis TickleCarlaMelenaNo ratings yet

- Gavotte Gavotte: ScarlattiDocument2 pagesGavotte Gavotte: ScarlattigsrgsdfNo ratings yet

- Active Participle in Egyptian ArabicDocument7 pagesActive Participle in Egyptian ArabicRaven SynthxNo ratings yet

- Todd Titon Jeff - The Life StoryDocument18 pagesTodd Titon Jeff - The Life StoryLazarovoNo ratings yet

- My GirlDocument2 pagesMy GirlAnonymous Y9ikfnZK2R100% (2)

- Too Tight (That Rag O'mine) Too Tight (That Rag O'mine) Too Tight (That Rag O'mine) Too Tight (That Rag O'mine)Document1 pageToo Tight (That Rag O'mine) Too Tight (That Rag O'mine) Too Tight (That Rag O'mine) Too Tight (That Rag O'mine)KeithHinchliffeNo ratings yet

- John Williams Prelude-From Suite in E, BWV 1006a (J.S. Bach)Document16 pagesJohn Williams Prelude-From Suite in E, BWV 1006a (J.S. Bach)Charles Gdn100% (1)

- Campbell, Lyle Mithun, Marianne - The Priorities and Pitfalls of Syntactic ReconstructionDocument22 pagesCampbell, Lyle Mithun, Marianne - The Priorities and Pitfalls of Syntactic ReconstructionMaxwell MirandaNo ratings yet

- Anu by Adrian LeggDocument8 pagesAnu by Adrian LeggArmando d'Esposito100% (1)

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart - Rondo KV-545-SonataDocument5 pagesWolfgang Amadeus Mozart - Rondo KV-545-SonataBahar OssarehNo ratings yet

- The Jewish Ukulele - Uke of CarlDocument17 pagesThe Jewish Ukulele - Uke of CarlNikki TuckerNo ratings yet

- Listen Up or Lose Out: How to Avoid Miscommunication, Improve Relationships, and Get More Done FasterFrom EverandListen Up or Lose Out: How to Avoid Miscommunication, Improve Relationships, and Get More Done FasterNo ratings yet

- Pragmatics 4Document2 pagesPragmatics 4Nolan BunesNo ratings yet

- Complete20content L1y22YAyiMsAJg 080708Document44 pagesComplete20content L1y22YAyiMsAJg 080708An AnNo ratings yet

- A Contrastive Study of Chinese and English Address FormsDocument5 pagesA Contrastive Study of Chinese and English Address FormsXiaojuanNo ratings yet

- Informal Speech: Alphabetic and Phonemic Text with Statistical Analyses and TablesFrom EverandInformal Speech: Alphabetic and Phonemic Text with Statistical Analyses and TablesNo ratings yet

- Tugas Sociolinguistics SurveyDocument12 pagesTugas Sociolinguistics SurveynurhadihamkaNo ratings yet

- Polite Request Strategies by Male Speakers of Yemeni Arabic in Male-Male Interaction and Male-Female InteractionDocument18 pagesPolite Request Strategies by Male Speakers of Yemeni Arabic in Male-Male Interaction and Male-Female Interactionwisam123456No ratings yet

- Attitudes and ApplicationsDocument5 pagesAttitudes and Applicationsmuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- Expectations For Natural' Ways of Talking: A Context-Dependent Perspective On Fixedness in ConversationDocument30 pagesExpectations For Natural' Ways of Talking: A Context-Dependent Perspective On Fixedness in ConversationaNo ratings yet

- Vietnamese Telephone OpeningsDocument26 pagesVietnamese Telephone OpeningsQuan nguyenNo ratings yet

- Compliments and Compliment Responses in Kunming ChineseDocument7 pagesCompliments and Compliment Responses in Kunming ChineseKatrina NacarNo ratings yet

- Style Context Register - FINALDocument3 pagesStyle Context Register - FINALakshayaNo ratings yet

- Polo KalDocument1 pagePolo Kalfarshan296015No ratings yet

- SECTION 15125 Pipe Expansion Joints 00000000 PART 1 - GENERAL 1.1 DescriptionDocument3 pagesSECTION 15125 Pipe Expansion Joints 00000000 PART 1 - GENERAL 1.1 DescriptionAnonymous yniiLtiNo ratings yet

- Janitor SinkDocument2 pagesJanitor Sinkfarshan296015No ratings yet

- 15-3-1 - Fire ProtectionDocument10 pages15-3-1 - Fire Protectionfarshan296015No ratings yet

- 13038Document2 pages13038uddinnadeemNo ratings yet

- 15-1-8 - Vibration Isolation and Noise ControlDocument5 pages15-1-8 - Vibration Isolation and Noise Controlfarshan296015No ratings yet

- Pumps: SECTION 15/1/5Document10 pagesPumps: SECTION 15/1/5farshan296015No ratings yet

- 15140Document5 pages15140uddinnadeemNo ratings yet

- 15-1-4 - Ventilation and Exhaust SystemDocument8 pages15-1-4 - Ventilation and Exhaust Systemfarshan296015No ratings yet

- Pumps: SECTION 15/1/5Document10 pagesPumps: SECTION 15/1/5farshan296015No ratings yet

- 15-1-6 - Chilled Water Piping SystemDocument10 pages15-1-6 - Chilled Water Piping Systemfarshan296015No ratings yet

- 15990Document6 pages15990uddinnadeemNo ratings yet

- 15-1-2 - Hvac DuctworkDocument15 pages15-1-2 - Hvac Ductworkfarshan296015No ratings yet

- 15 1 3 Mechanical InsulationDocument7 pages15 1 3 Mechanical Insulationfarshan296015No ratings yet

- SF-11 Roof Axial Fan - Rev 00 July 2018 PDFDocument3 pagesSF-11 Roof Axial Fan - Rev 00 July 2018 PDFfarshan296015No ratings yet

- Transfer Pumps CalculationsDocument4 pagesTransfer Pumps Calculationsfarshan296015No ratings yet

- 01 1419-Use of SiteDocument2 pages01 1419-Use of Sitefarshan296015No ratings yet

- 15-1-1 - Air Conditioning SystemDocument12 pages15-1-1 - Air Conditioning Systemfarshan296015No ratings yet

- 01 3100-Project CoordinationDocument1 page01 3100-Project Coordinationfarshan296015No ratings yet

- Turf Catalog 2016Document188 pagesTurf Catalog 2016farshan296015No ratings yet

- Reducer Fittings Decrease Pipe Size To Avoid FailureDocument7 pagesReducer Fittings Decrease Pipe Size To Avoid Failurefarshan296015100% (1)

- Compliance With Ashrae (HAP)Document7 pagesCompliance With Ashrae (HAP)farshan296015No ratings yet

- Defining Air Systems (HAP)Document42 pagesDefining Air Systems (HAP)farshan296015No ratings yet

- Inspector's Test Instructions PDFDocument1 pageInspector's Test Instructions PDFfarshan296015No ratings yet

- Ventilation Calculations Knowledge Base - Design Master SoftwareDocument3 pagesVentilation Calculations Knowledge Base - Design Master Softwarefarshan296015No ratings yet

- HAP - Hourly Analysis Program TutorialDocument58 pagesHAP - Hourly Analysis Program Tutorialfarshan296015No ratings yet

- AMCA Fan Performance PDFDocument16 pagesAMCA Fan Performance PDFthevellin154No ratings yet

- Electrical Appliance Typical Energy Consumption Table PDFDocument2 pagesElectrical Appliance Typical Energy Consumption Table PDFJavier Lemus100% (1)

- 15 5 4 Plumbing FixturesDocument1 page15 5 4 Plumbing Fixturesfarshan296015No ratings yet

- GI Sheet Kg-m2Document1 pageGI Sheet Kg-m2farshan296015No ratings yet

- Tazkira e Aulia e Karam ADocument3 pagesTazkira e Aulia e Karam ASidra ManoNo ratings yet

- Black Guerilla EconomicsDocument1 pageBlack Guerilla EconomicsManigaMotepNo ratings yet

- Fiqh For ChildrenDocument61 pagesFiqh For ChildrenSarafa Abdulazeez100% (1)

- Presentation-Tawheed 101 CompleteDocument30 pagesPresentation-Tawheed 101 Completedapper18100% (3)

- Nikah NamaDocument3 pagesNikah NamaBadsha Mia83% (12)

- Time ManagementDocument5 pagesTime ManagementChris AdaminovicNo ratings yet

- DR - Thagfan Diagnostic Center E RegisterDocument3 pagesDR - Thagfan Diagnostic Center E RegisterKh FurqanNo ratings yet

- Tuskish Basics 12Document115 pagesTuskish Basics 12Antonis HajiioannouNo ratings yet

- Kabir Saheb Shabad 1Document3 pagesKabir Saheb Shabad 1freestuff_80No ratings yet

- Workers Vanguard No 155 - 29 April 1977Document12 pagesWorkers Vanguard No 155 - 29 April 1977Workers VanguardNo ratings yet

- Forged Powr of AttorneyDocument77 pagesForged Powr of AttorneySaddy MehmoodbuttNo ratings yet

- Renaissance Traditions For Mage: Dark AgesDocument12 pagesRenaissance Traditions For Mage: Dark AgesbrotherbenkoNo ratings yet

- Persian LiteratureDocument6 pagesPersian LiteraturefeNo ratings yet

- Sheikh FaheemDocument54 pagesSheikh Faheemapi-3745637No ratings yet

- Dubai UAE InformationDocument28 pagesDubai UAE InformationsefdeniNo ratings yet

- Recitation of Sura For RizqDocument28 pagesRecitation of Sura For RizqHusain R Saeed83% (6)

- Djordjevic - Religious-Ethnic Panorama of The BalkansDocument18 pagesDjordjevic - Religious-Ethnic Panorama of The BalkansmargitajemrtvaNo ratings yet

- Campus: Cia UneaseDocument56 pagesCampus: Cia UneaseMark CNo ratings yet

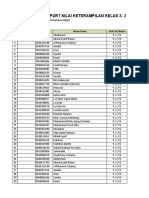

- Format Import Nilai Keterampilan Kelas X. 2 TBSMDocument8 pagesFormat Import Nilai Keterampilan Kelas X. 2 TBSMDjalimin SurNo ratings yet

- Haseeb Javed Ciit BCS 128 (6B) Pakistan Studies: Topic: Mughal Empires and Downfall of Muslim SociteyDocument20 pagesHaseeb Javed Ciit BCS 128 (6B) Pakistan Studies: Topic: Mughal Empires and Downfall of Muslim SociteyNida TocyoNo ratings yet

- Al - FarabiDocument3 pagesAl - FarabiHussainJalaluddinNo ratings yet

- The Night Prayer in Ramadaan - Al-AlbaaneeDocument30 pagesThe Night Prayer in Ramadaan - Al-AlbaaneeUponSunnahNo ratings yet

- Sajdah SahwDocument21 pagesSajdah SahwFarha FerozeNo ratings yet

- Ucc and Judicial TrendDocument10 pagesUcc and Judicial TrendabhishekNo ratings yet

- Most Blessing Dua's (Lots of Important Dua's)Document15 pagesMost Blessing Dua's (Lots of Important Dua's)Hani KazmiNo ratings yet

- English Language ScrapbookDocument7 pagesEnglish Language ScrapbookMuhd AsyrafNo ratings yet

- Ijm+3 AnswersDocument4 pagesIjm+3 Answersmasho khanNo ratings yet

- Business DirectoryDocument76 pagesBusiness Directoryaries200675% (4)

- Biodata XII IPS 2Document15 pagesBiodata XII IPS 2rezafiansyahNo ratings yet

- Kasif - Subject Verb Agreement, KKBGVDocument36 pagesKasif - Subject Verb Agreement, KKBGVAfsana KarimNo ratings yet