Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sport Sponsorhip Team Support PDF

Uploaded by

DedeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sport Sponsorhip Team Support PDF

Uploaded by

DedeCopyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [University of Bucharest ]

On: 08 March 2015, At: 11:24

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered

office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Marketing Communications

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjmc20

Sport sponsorship, team support and

purchase intentions

a

Aaron Smith , Brian Graetz & Hans Westerbeek

School of Sport, Tourism and Hospitality Management , Faculty

of Law and Management , La Trobe University , Melbourne,

Australia

b

School of Business , Faculty of Law and Management , La Trobe

University , Melbourne, Australia

Published online: 31 Oct 2008.

To cite this article: Aaron Smith , Brian Graetz & Hans Westerbeek (2008) Sport sponsorship,

team support and purchase intentions, Journal of Marketing Communications, 14:5, 387-404, DOI:

10.1080/13527260701852557

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13527260701852557

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the

Content) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,

our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to

the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions

and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,

and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content

should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources

of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,

proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or

howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising

out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/termsand-conditions

Journal of Marketing Communications

Vol. 14, No. 5, December 2008, 387404

Sport sponsorship, team support and purchase intentions

Aaron Smitha*, Brian Graetzb and Hans Westerbeeka

a

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

School of Sport, Tourism and Hospitality Management, Faculty of Law and Management,

La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia; bSchool of Business, Faculty of Law and

Management, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

This research assessed the influence of team support and perception of sponsors

on the purchase intentions of sport consumers. In a case study of a not-for-profit,

membership-based Australian professional football club, 1647 respondents

reported their perceptions of team support, sponsor integrity and purchase

intentions for the sponsors products. Results revealed that the key pathway to

purchase intention is associated with fan passion and a perception of sponsor

integrity. This implies that the best mechanism for sponsor return on investment

comes in the form of activities to bolster both passion for the team and

perceptions of sponsor integrity.

Keywords: consumer behaviour; sport sponsorship; purchase intention

Introduction

Despite its importance and the proliferation of work on sponsorship in general, the

nature of the relationship between sponsorship and consumer purchase intentions

remains unclear. Meenaghan and OSullivan (2001) lamented that the research into

sponsorship has predominantly focused either on management practices or on recall

and recognition. Furthermore, they noted that awareness and association testing

provides only superficial data about the nature of consumer reaction to, and

engagement with, sponsorship. A paucity of empirical work seeks to explain the

machinations of the relationship between sport sponsors and sport consumers. The

importance of bolstering the limited empirical work in this area is amplified as some

case study descriptions suggest that under the right conditions, sponsorship can be

more effective than traditional advertising or other promotional activities (Verity

2002). This research reports on the results from a survey of members of a

professional Australian (rules) Football League club. It aims to identify the key

variables in the sponsorship relationship and the processes that influence members

purchase intentions toward the major (naming rights) sponsors products. Members

are individuals who have paid an annual fee to belong to a not-for-profit sporting

club, comprising a suite of ticket and merchandise benefits along with the right to

vote in the annual general meeting and in elections for positions in the Board of

Management.

This research employs the conventional definition of sport sponsorship proposed

by Meenaghan (1991). Sponsorship therefore involves an investment, in cash or

kind, in a sport property in return for access to the exploitable commercial potential

associated with that property. Return on investment has proven troublesome to

sponsors associated with small sport properties (Ashill, Davis, and Joe 2000;

*Corresponding author. Email: aaron.smith@latrobe.edu.au

ISSN 1352-7266 print/ISSN 1466-4445 online

# 2008 Taylor & Francis

DOI: 10.1080/13527260701852557

http://www.informaworld.com

388 A. Smith et al.

Jackson, Barry, and Scherer 2001; Roy and Graeff 2003). However, there is

persuasive evidence suggesting that sponsors should change their focus from raw

volume of exposure to image matching or fit (Lachowetz et al. 2002), complemented

by an awareness of the dangers of invasive marketing techniques (Irwin et al. 2003).

This research aims to explore the determinants of purchase intention and

processes of decision making about the sponsors products in the membership base

of a professional sport club in Australia. It reports on the results of a 21-item

instrument comprising a beliefsattitudesintentions hierarchy of effects framework,

distributed to the membership population of a professional Australian football club.

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

Literature and conceptual background

Measures of purchase behaviour focus on the direct effect of sponsorship on sales.

The difficulty, of course, lies in isolating the effect of sponsorship from other

activities within the promotion mix or from variables in the market (Miles 2001;

Miyazaki and Morgan 2001). Just as with other major announcements, new

sponsorships have been shown to have an effect on the value of a companys share

price (Clark, Cornwell, and Pruitt 2002). Although troublesome, assessments of

purchase intention have been employed to help ascertain the impact of sponsorship

activities.

According to Pope and Voges (2000), consumers intention to purchase can be

derived from two predominant influences: first, a positive attitude towards the

brand; and second, brand familiarity, which is obtained from brand exposure and

prior use. In addition to these two factors, suggestive evidence points to the relevance

of team support, and sponsor integrity and fit. However, as Hoek, Gendall, and

Theed (1999) cautioned, the link between awareness and increased purchase

behaviour is tenuous, even though exposure is the key element in determining the

value of a sponsorship (Cornwell et al. 2000). Furthermore, the familiarity with a

sponsors brand emanating from exposure and sponsorship awareness has been

claimed to increase consumption values (Levin, Joiner, and Cameron 2001; Pope

1998).

It may be premature to conclude that brand familiarity is sufficient to stimulate

purchase behaviour. For example, the impact of perceived sponsor commitment may

also be relevant. Farrelly and Quester (2003) indicated that the sponsored sport

organizations actions do not directly influence the sponsors commitment to the

relationship. They suggested that low levels of market orientation by the property

might actually encourage the sponsor toward a deeper level of commitment to

compensate. Low exposure (and perhaps consumer awareness) can stimulate a

greater sponsor commitment to the relationship. Chadwick (2002) proposed that it is

crude to conceive of sponsor commitment to pivot around the financial transaction.

He argued that it instead demands a multi-faceted view of commitment that

emphasizes a collaborative and relational perspective. Grohs, Wagner, and Vsetecka

(2004) provided evidence that sponsor-property fit, event involvement and exposure

are the key factors predicting sponsor recall. The magnitude of image transfer

depends upon sponsorship leveraging and the sponsor-property fit (Grohs, Wagner,

and Vsetecka 2004).

Results from Speed and Thompsons (2000) data indicated that sponsor-event fit,

perceived sincerity of the sponsor, perceived ubiquity of the sponsor and attitude

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

Journal of Marketing Communications

389

toward the sponsor are central in eliciting an advantageous response from the

sponsorship association. Research considering the impact of sponsor-event fit on

cognitive and affective responses has indicated that sponsors with high brand equity

are perceived as more congruent sponsors than those with low brand equity (Roy

and Cornwell 2003). Thus, well known brands have a superior opportunity for brand

building through sponsorship. In turn, sponsor-event congruence has been shown to

be associated with favourable attitudes towards the sponsor.

The nature of team support has also been established as a precursor to

consumers purchase intentions. Gwinner and Swansons (2003) data supported the

hypothesis that highly identified sport fans are more likely to exhibit sponsor

recognition, a positive attitude toward the sponsor, sponsor patronage and

satisfaction with the sponsor. These outcomes were linked to three antecedents:

prestige, fan associations and domain involvement (the personal relevance of a

particular object, situation or action). The authors defined team identification as

spectators perceived connectedness to a team and its performance. Therefore, it is a

specific form of organizational identification, and one that gives rise to the positive

associations that may encourage purchase intentions. Positive attitudes toward a

sponsor have further been positively associated with favourable perceptions and

intentions to purchase a sponsors product (Speed and Thompson 2000). Wann et al.

(2001) observed that highly identified fans evaluate in-group members higher than

out-group members. It is unclear whether this positive association extends to

sponsors (Wann and Branscombe 1993).

Identification represents the final mechanism of fan attachment (Ferrand and

Pages 1996; Jones 2000; Wiley, Shaw, and Havitz 2000), and refers to the association

between an individuals self-concept and the sport object. Identification is achieved

when individuals are motivated toward the sport team, club or athlete for reasons of

constructing a self-concept. Self-concept motives include the desire for belonging,

group affiliation, tribal connections and vicarious achievement (Fink, Trail, and

Anderson 2002; Hughson 1999; Morris 1981; Wann 1995; Wann and Branscombe

1993). When motivated by these factors, a persons sense of self may be associated

with the team and self-esteem may be extracted from team success; the group (tribe,

club, team) may be seen as an extension of the self. In other words, the more a fan is

motivated to construct a sense of self through the sport object, the more closely they

will become emotionally attached to it. There is, in fact, evidence suggesting that of

all the mechanisms of fan attachment, it is identification which bears the greatest

influence over whether a fan will develop a psychological or emotional connection to

the team (Fink, Trail, and Anderson 2002).

Group identification is a pivotal mediator of social perception (Wann and Grieve

2005). Fans with greater identification are more likely to attend games, purchase

merchandise, spend more on tickets and products, and remain loyal (Fink, Trail, and

Anderson 2002; Madrigal 1995; Murrell and Dietz 1992; Wann and Branscombe

1993). In other words, the outcome of a strong psychological connection to a team is

loyalty, where support, including consumption behaviours, may continue regardless

of circumstances (James, Kolbe, and Trail 2002). Sponsors may have reason to

assume that they will be perceived as an ally of the high identification fan (Hoek,

Gendall, and Sanders 1993). They may even attempt to amplify the level of

identification through celebrity endorsement. A company may further choose to go

beyond celebrity endorsement and engage representative industry associations and

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

390 A. Smith et al.

groups on their behalf as an approach to influencing consumer purchase intentions

(Daneshvary and Schwer 2000).

Lafferty and Goldsmith (1999) determined that while purchase intentions do

indeed grow with corporate credibility, the growth is not significantly related to

endorser credibility. Earlier research by Ohanian (1991) concerning the relationship

of attractiveness, trustworthiness, and expertise to intention to purchase showed that

only the perceived expertise of the celebrity endorser was significant in predicting

purchase intentions. Indeed, Tripp, Jensen, and Carlson (1994) demonstrated in their

experimental study that as the number of celebrity advertisement exposures

increased, there was a corresponding deterioration in consumer intention to

purchase. Silvera and Austad (2004) determined that product attitudes could be

predicted by inferences about the endorsers liking for the product and by attitudes

toward the endorser. This relationship implies that a progression from beliefs to

attitudes is important, as crudely predicted by hierarchy of effects models.

Hierarchy of effects models describe the assumption that consumers progress

through escalating mental stages when they make buying decisions, and when they

respond to marketing or other communications about a product. One of the earliest

versions of the model is attributed to Strong (1925) in the form of awareness

interestdesireaction (AIDA). Ambler (1998) claimed that there is consensus that

decision-making structures include cognitive, affective and behavioural components,

but that there is scant evidence delineating the sequence and timing of the steps. This

cautious undertone was highlighted by Barry and Howard (1990) as well as

Vakratsan and Ambler (1999).

One of the central challenges to hierarchy of effects models revolves around the

impact of involvement, particularly as a mediating variable. Meenaghans (2001)

framework concerning the effects of commercial sponsorship on consumers revolves

around the key variables of goodwill, image, involvement and consumer response.

His models fundamental premise is that the consumers degree of involvement with,

and knowledge about, the sponsored activity along with the associated goodwill

directed to the sponsor, drive consumer response to sponsorship.

Madrigal (2001) employed a beliefsattitudeintentions hierarchy to investigate

consumers connections to sport teams and their corporate sponsors. The emotional

connection of consumers was interpreted through a social identity theory lens where

a consumers self-concept is derived from membership to a group. His study reported

on the influence of consumers beliefs about sponsorship, the perceived importance

of those beliefs, identification with the sponsored sport team and consumers

purchase intention attitudes. Madrigal counselled that consumer passion for the

sport team is the pivotal variable. In addition, he concluded that favourable beliefs

about the benefits provided to the sport property from the sponsor are positively

related to attitudes toward buying products from that sponsor. Fan identification

with the sport property and the opportunity for sponsors to influence consumers

beliefs about the benefits of association, are the key lessons.

From a theoretical standpoint, Madrigals research was pivotal in shedding light

on the manner in which the beliefattitudesintentions hierarchy unfolds in

association with a sport sponsorship. He concluded that the role of inter-attitudinal

relationships was central to the formation of social identity with the sport team; a

process preceding attitudinal development. Thus, the most important aspect of the

hierarchy related to the tendency of consumers to hold favourable attitudes towards

Journal of Marketing Communications

391

those factors reflective of their own identities. Consumers, therefore, will forge

positive associations with sponsors that support the sport properties that exemplify

and house these identities, culminating in bolstered purchase intentions.

The aim of the research reported here is to identify the key linkages between

sport fans, team support and sponsorship, together with the processes that influence

members purchase intentions toward the chief sponsors products. This research

embraces Madrigals (2001) beliefattitudesintentions hierarchy. However, the

specific objective remains to ascertain the manner in which team support and

perceptions of sponsor integrity affect fan receptiveness to sponsorship and

ultimately their intention to purchase sponsors products.

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

Data and method

The data for this analysis are taken from a survey of the membership base of a

professional Australian Football League club. The club is not-for-profit and consists

of members who elect a board of governance. A mail-out questionnaire was sent to

the population of club members. In total 1703 responses were received, of which

1647 were usable, representing a response rate of 8.5 % (N519,295). This low

response rate represents a limitation of this study as it presents the possibility of a

bias due to the self-selection of respondents.

The instrument developed for this research was informed by previous studies of

similar issues and populations (for example, Tapp 2004; Speed and Thompson 2000;

Richardson and ODwyer 2003) as well as the more general approaches of Lee,

Sandler, and Shani (1997), Daneshvary and Schwer (2000) and Madrigal (2001).

Items were measured on a seven-point Likert scale ranging between strong

agreement and strong disagreement. Some 15 of these 21 items are used in the

analyses reported below; six items that did not contribute to the measurement of

coherent constructs were discarded. Items relating to socio-demographic attributes

and club membership were also included in the questionnaire.

Respondent attributes are summarized in Table 1. Two out of three respondents

were male and most had post-secondary education (technical college or university).

They represent a range of income levels, with one in eight respondents earning less

than $AUS25,000 ($US21,000; J15,000) per annum, two in five earning between

$AUS50,000 ($US42,000; J30,000) and $AUS100,000 ($US84,000; J60,000) per

annum, and one in eight earning incomes in excess of $AUS100,000 ($US84,000;

J60,000) per annum. Respondents are also well distributed by age, with 14% aged

less than 30 years, 46% aged 3049 years, 36% aged 5064 years and 4% aged 65 and

over. Respondents had been members for an average of 13.6 years and attended up

to 30 football matches per year, with the average being nine matches. These

distributions, together with the large number of responses received, suggest that

responses are broadly representative of the clubs membership. However, although

the respondents were demographically typical, their sponsorship attitudes may not

have been because of their willingness to participate in the survey where others did

not.

A series of exploratory factor analyses was applied to the set of items relating to

team support, sponsorship and purchase intentions to identify optimal combinations

of variables for measurement purposes. Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) was used in

this analysis. The exploratory factor analysis revealed a number of key dimensions

392 A. Smith et al.

Table 1. Socio-demographic and membership profile of respondents.

N

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

Gender

Male

Female

Percent

1078

520

67

33

Age

Less than 30 years

3049 years

5064 years

65 years and older

227

752

592

73

14

46

36

4

Education

Secondary

Tertiary

University

634

386

602

39

24

37

Income

Less than AUS$25k (US$21k; J15k)

AUS$2550k (US$2142k; J1530k)

AUS$50100k (US$4284k; J3060k)

More than AUS$100k (US$84k; J60k)

189

518

639

200

12

34

41

13

Mean

Years of membership

Matches attended per season

13.62

9.07

relevant to this analysis. These were team support (passionate, positive), sponsor

integrity, sponsor receptiveness and purchase intentions. The items comprising

each dimension, the exact question wording, and the factor loadings and

reliabilities obtained are presented in Table 2. As there are causal interrelationships amongst latent factors, a single pooled analysis is not appropriate.

Hence, separate factor analyses were conducted as shown by the numbering of items

in Table 2.

Measurement

The questionnaire included several items about strength of team support.

Exploratory factor analysis revealed two separate dimensions passionate (three

items) and positive (two items). The use of oblique rotation to simplify factors is

justified in this analysis in view of the strong inter-factor correlation (r50.59)

(Tabachnick and Fidell 2001). Factor loadings exceed 0.64 and the reliability of both

measures is very high. Off-factor loadings (not shown in Table 2) are negligible, the

highest being 0.18.

Sponsor receptiveness is a summated index, which captures three separate

aspects of receptiveness to the sponsors products and services: openness to further

information, interest in learning more about the sponsor and knowledge of the

sponsors business. A high score indicates that respondents are open to learning and

becoming more knowledgeable about the sponsors products and services.

Journal of Marketing Communications

393

Table 2. Fans, sponsorship and purchase intentions: item wording and rotated factor

loadings.

Item wording

Passionate supporter (Cronbach a50.80)

1. I passionately support the club

2. I love the club

3. I passionately follow another team in the AFL

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

Positive supporter (Cronbach a50.73)

4. Win or lose, I always support my team in a positive manner

5. I always talk positively about the club

Loadinga

0.780

0.728

20.641

0.815

0.672

Sponsor receptiveness (Cronbach a5not applicable)

1. I am interested in learning more about the sponsors of the club

2. I would welcome receiving information about the products and services of

sponsors Summated index

3. I know more about the business of the sponsors since they started

sponsoring the club

Sponsor integrity (Cronbach a50.68)

1. The existing sponsors and the club fit well together

2. I automatically like all sponsors of the club because they support my team

financially

3. I feel that sponsors of the club show a genuine interest in the club and its

supporters

It is good to see a big company sponsoring a local football team

Purchase intention (Cronbach a50.80)

1. I am more likely to buy products from an organization that sponsors the

club

2. I will always consider buying the products and services of the club sponsors

before considering the products and services of non-sponsors

3. I would consider using the products or services of sponsors

0.693

0.580

0.569

0.504

0.819

0.772

0.673

Factor loadings obtained using Principal Axis Factoring and Direct Oblimin rotation.

Sponsor integrity is a composite measure of respondents views about the

relationship between the sponsor and the sponsored sporting team. It encompasses

genuineness, (sponsors show a genuine interest in the club and its supporters), fit (the

sponsors and the team fit well together), virtue (it is good to see a big company

sponsoring local football) and affection (I like sponsors because they support the

team financially).

Finally, the dependent variable, purchase intentions, comprises three items

reflecting respondents willingness to support their teams sponsor by using and

purchasing products or services. The items comprising this measure are willingness

to use the products or services of sponsors, willingness to buy products from an

organization that sponsors the team, and willingness to consider the products or

services of sponsors before considering the products or services of non-sponsors. The

items are positively correlated, have loadings in excess of 0.67 and strong reliability

(a50.80). Regression factor scores have again been used to obtain an optimal

394 A. Smith et al.

summary of responses. The scale of measurement for the five composite variables

has been adjusted so that all scores fall within a range of 010 points.

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

Analysis

The core of the analysis reported below focuses on the relationship between

supporters (fans), sponsor integrity, brand receptiveness and purchase intentions.

These relationships are examined using both bivariate Pearson correlations and

multivariate statistical techniques. Multiple regression is used to estimate the causal

model presented in Figure 1. In this model, purchase intention is dependent on team

support, sponsor integrity and sponsor receptiveness which themselves are causally

inter-related as shown by arrows in Figure 1. Team support is represented by three

variables: passionate fans, positive fans and match attendance. Sponsorship is

represented by two variables: sponsor receptiveness and sponsor integrity.

A path analysis approach with incremental regressions and reduced-form

equations is used to estimate total as well as direct causal effects (Kline 1998). Direct

effects represent the unique effect that each variable has on purchase intentions,

controlling for all exogenous and endogenous variables in the model. Total causal

effects are the sum of direct effects and indirect effects mediated through intervening

variables and are estimated here using equations that omit intervening variables, in

the manner of Alwin and Hauser (1975). As shown in Figure 1, team support and

sponsor integrity will have indirect effects on purchase intention, whereas sponsor

receptiveness has only a direct effect, so its total and direct effects will be equivalent.

Results

The distribution of scores on the five composite variables in this analysis is

summarized in Table 3. Respondents are found to be strongly passionate supporters

of their team with a mean score of nine on the 10-point scale. Not all members are

passionate supporters, however, but the distribution is none the less strongly

negatively skewed and peaked at high scores, indicated by the high positive value for

Figure 1. Explanatory model: team support, sponsorship and purchase intention.

Journal of Marketing Communications

395

Table 3. Fans, sponsorship and purchase intentions: univariate statistics.

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

Composite measure

Range

Mean

Std dev

Skewness

Kurtosis

Fans

Passionate fans

Positive fans

010

010

9.02

8.03

1.67

1.79

22.93

21.48

10.38

2.75

Sponsorship

Sponsor receptiveness

Sponsor integrity

Purchase intention

010

010

010

5.76

7.29

8.31

2.20

1.60

1.35

20.30

20.68

20.81

20.27

1.32

0.85

kurtosis. Respondents are also strongly positive in their support for their team,

although the mean score is one point lower than for passionate support. There is also

more diversity of views expressed on this measure, reflected by the considerably

lower values for skewness and kurtosis. The strongly passionate and mostly positive

support expressed for the team is consistent with expectations for respondents who

are all club members.

Table 3 also shows there is a moderate degree of receptiveness amongst fans to

the commercial appeal of the teams major sponsor. Scores are close to normally

distributed, with a mean score near to the mid-point of the scale and values for

skewness and kurtosis close to zero. The perceived level of integrity of the sponsor is

somewhat higher, with a mean score in excess of seven points. Although most fans

have a highly favourable view about the sponsors integrity, there is some variation

around this, including a small proportion of respondents who do not rate the

sponsors integrity highly at all. Finally, respondents express strong purchase

intentions in relation to the sponsors services. The mean score is eight points and

most responses fall within the upper half of the scale, with the modal response being

an unequivocal intention to consider the sponsors services. Again, however, a small

proportion of respondents are not willing to consider using or buying the sponsors

services.

Table 4. Fans, sponsorship and purchase intention: correlations with socio-demographic and

membership attributes.a

Composite variables

Gender

Age

Fans

Passionate fan

Positive fan

20.08*

20.12*

20.06

0.01

20.09*

20.06

20.14*

0.02

20.03

20.11*

0.01

20.03

Sponsorship

Sponsor receptiveness

0.07*

Sponsor integrity

20.01

Purchase intention

0.02

*Statistical significance at P,0.01.

a

Pearson correlations.

Education Income

Years of

membership

Match

attendance

20.11*

20.10*

0.08*

0.03

0.21*

0.17*

0

20.08*

0.04

0.04

0.11*

0.12*

0.05

0.07*

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

396 A. Smith et al.

Table 4 presents correlations between the socio-demographic attributes of

respondents and fans, sponsorship and purchase intention. These correlations

reveal only minor variations in responses. Passionate supporters are marginally more

likely to be female, have marginally lower education and income, have been club

members for marginally longer and attend more matches during the year. Supporters

who always remain positive about their team are also more likely to be female, with

lower income and attend more matches. Males, younger respondents and those

attending more matches are marginally more receptive to the sponsors products and

services. Sponsor integrity is weakly correlated with education, income (both

negative) and match attendance. Purchase intention is related only to match

attendance and then only very weakly. Overall, variations in team support, sponsor

impact and purchase intention are related weakly to respondent attributes. The

strongest correlations are between passionate and positive fans and match

attendance, measures that are used collectively as indicators of team support in

the explanatory models that follow.

Table 5 presents the results of the regression analysis estimating parameters for the

explanatory model for purchase intentions depicted in Figure 1. The table presents both

direct effects (depicted by the arrows in Figure 1) and total causal effects (the sum of

direct and indirect effects, estimated here using reduced-form equations). The results

shown in Table 5 indicate that socio-demographic variables have little impact on

purchase intentions. Age is the only significant effect (older people have marginally

stronger purchase intentions) but this direct effect is offset by an indirect effect in the

opposite direction, with older people less receptive to further information from the

sponsor. As a result, age has no significant effect overall on purchase intentions.

Table 5. Direct and total causal effects for purchase intentions.a

Independent variables

Direct effects

b

Control variables

Gender

Age

Education

Income

Years of membership

Total effects

b

0.012

0.046

0.063

0.054

0.001

0

0.09*

0.05

0.04

0

0.079

0.007

0.004

0.007

0.005

0.03

0.01

0

0

0.04

20.010

0.094

0.020

20.04

0.12*

0.03

0

0.210

0.123

0

0.26*

0.16*

Sponsor integrity

0.325

0.39*

0.439

0.52*

Sponsor receptiveness

R squared

Standard error of the estimate

F, significance

0.184

0.30*

0.184

0.436

0.9976

96.50, P,0.001

0.30*

Team support

Match attendance

Passionate fan

Positive fan

*Statistical significance at P,0.001.

Unstandardized (b) and standardized (b) regression coefficients.

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

Journal of Marketing Communications

397

Team support represents a more important set of explanatory variables. Passionate

supporters have significantly higher purchase intentions, both directly and in total. The

indirect effect arises primarily because passionate supporters have significantly higher

regard for sponsor integrity. Positive supporters are also more likely to use and

purchase the sponsors products, although only the total effect is statistically

significant. In this case, the indirect effect arises both because of a positive link with

sponsor integrity and through increased receptiveness to the sponsors product. In

contrast, frequent match attendance has no significant impact on purchase intentions.

In comparison with team support, sponsor integrity is an even more important

determinant of purchase intentions and the single most important effect overall. Its

direct effect is more than three times larger than the effect of passionate support and

its total effect is twice as large. The indirect effect arises from a substantial link

between sponsor integrity and sponsor receptiveness. Fans who believe the sponsor

has integrity are more receptive to information provided by the sponsor and are

more likely to use their products. Moreover, each point of sponsor integrity (as

measured on the 010 scale) enhances purchase intentions directly by one-third of a

point and by close to half a point in total. This means that a two-point upward shift

in sponsor integrity increases purchase intentions by almost 9% on average, and a

three-point upward shift by 13% on average.

Sponsor receptiveness also has a substantial impact on purchase intentions. The

impact is less than that of sponsor integrity but it remains the second most important

explanatory variable in the model. Collectively, the explanatory variables in the

model account for 44% of the variance in purchase intentions, with very little of this

explained variance attributable to socio-demographic attributes, membership

duration or match attendance.

Finally, Table 6 shows standardized and unstandardized regression coefficients

and goodness of fit statistics for the endogenous variables in the model, including

components of indirect effect referred to above. The results show that younger

people, members of longer duration, positive fans and, most importantly by far,

sponsor integrity all have statistically significant effects on sponsor receptiveness.

Perceptions of sponsor integrity, however, are not influenced by socio-demographic

attributes, membership duration or match attendance, but passionate and positive

team support both have significant effects.

In summary, socio-demographic variables, duration of club membership and

match attendance all have negligible impacts on purchase intentions. Instead, the key

determinants of purchase intention are sponsor integrity, sponsor receptiveness and

team support. The critical pathways to purchase intention amongst members of this

Australian football club are summarized in Figure 2. The key steps in the purchase

intention chain involve fans who are passionate and positive supporters of their

team. These fans rate sponsor integrity much more highly, and this in turn enhances

receptiveness to the sponsors message and purchase intention itself. These steps

provide clear evidence of ways in which sporting clubs and sport sponsorship can

work together for mutual benefit.

Discussion

The exploratory factor analysis applied here delivered a number of dimensions that

appear consistent with hierarchy of effects models. For example, five dimensions

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

Team support

Dependent

variables

Independent

variables

Control variables

Gender

Age

Education

Income

Years of

membership

Team support

Match attendance

Passionate fan

Positive fan

Sponsor integrity

R squared

Standard error of

the estimate

F, significance

Sponsor receptiveness

Sponsor integrity

Match attendance

Passionate fan

Positive fan

0.339

20.140

20.097

20.028

0.019

0.07

20.16*

20.05

20.01

0.11*

0.092

20.011

20.111

20.130

0

0.03

20.02

20.08

20.07

0

21.68

20.097

20.308

20.385

0.118

20.15*

20.05

20.07

20.07

0.29*

20.234

20.090

20.128

20.111

0.014

20.06

20.13*

20.08

20.06

0.11*

20.391

20.021

20.084

20.100

0.002

20.10*

20.03

20.05

20.05

0.02

0.031

0.123

0.247

0.07

0.09

0.20*

0.013

.285

0.178

0.620

0.04

0.30*

0.20*

0.45*

0.278

1.835

0.232

1.388

0.125

4.717

0.037

1.670

0.020

1.788

53.68, P,0.001

47.85, P,0.001

38.04, P,0.001

10.93, P,0.001

5.85, P,0.001

*Statistical significance at P,0.001.

a

Unstandardized (b) and standardized (b) regression coefficients.

398 A. Smith et al.

Table 6. Explanatory models for endogenous variables: sponsor receptiveness, sponsor integrity and team support.a

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

Journal of Marketing Communications

399

Figure 2. Key pathways to purchase intention (standardized regression coefficients, omitting

minor effects).

Note: *indicates statistical significance at P,.001.

were highlighted that align broadly with Madrigals (2001) beliefattitudes

intentions hierarchy. The presence of passionate and positive fans reflects a

constituting and central element of their identities (passionate) as well as their selfconcept (positive). Given that respondents can be described as strongly passionate

or strongly positive, it might be assumed that the respondents are strongly

identified and involved. This is further corroborated by results in Table 4; passionate

and positive supporters are more likely to attend more matches, which in turn leads

to higher levels of merchandise purchases, higher spending on tickets and products,

and higher levels of team loyalty (Fink, Trail, and Anderson 2002; Madrigal 1995;

Murrell and Dietz 1992; Wann and Branscombe 1993). A strong psychological

connection to a team leads to loyalty, and loyalty is often expressed in support

regardless of circumstances (James, Kolbe, and Trail 2002). It is clear from the

results that the underpinning passionate beliefs held by members about their club,

and their attitudes to sponsors, have an influence of the formation of purchase

intentions.

A third dimension identified as sponsor integrity expresses the views respondents

hold about the sponsor. Much like the first two dimensions, sponsor integrity is

reflective of the attitudes respondents have, in this case, about what it takes to be a

good sponsor. A high level of perceived sponsor integrity is reported in this study.

The attitude towards sponsors is expressed in sponsor receptiveness and respondents

report a moderate openness towards receiving information about sponsors, and feel

that there is a reasonable fit between the sponsors and the team. As Speed and

Thompson (2000) argue, the level to which sponsor and the sponsored entity fit

together, the degree of perceived sponsor sincerity, and hence the level of positive

attitude toward the sponsor, are critical in delivering positive consumer responses to

the sponsorship association. In turn, team support impacts upon sponsor

receptiveness and directly on purchase intentions.

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

400 A. Smith et al.

Socio-demographic variables have little effect on purchase intentions. This

finding provides support for shifting the attention from socio-demographically

targeted marketing strategies to strategies that take a more holistic view of the

sponsorship arrangement. In line with Pope and Voges (2000), respondents

intention to purchase was shown in this research to be influenced by a positive

attitude towards the brand, or more specifically, by a positive view in regard to the

integrity of the sponsor. This finding further undermines the popular assumption

that exposure is the uppermost determinant of sponsorship success, and therefore a

sound platform for its impact measurement. Rather, there is insufficient evidence to

conclude that building brand familiarity is enough to stimulate intention to purchase

perceptions. The issue of perceived sponsor commitment may be more important

than has previously been highlighted. This research provides some evidence that the

level of perceived commitment of the sponsor to the team positively impacts the

intention to purchase the sponsors products. The constituting items of sponsor

integrity support Chadwicks (2002) contention that sponsor commitment revolves

around a multi-faceted view of commitment emphasizing a collaborative and

relational perspective. That the perceived fit between sponsor and sponsored entity

is important, as evidenced by results from Speed and Thompson (2000) and Grohs,

Wagner, and Vsetecka (2004), is further supported by the outcomes of this study.

This research provides strong support for the proposition that team support and

consumers purchase intentions are intertwined (Gwinner and Swanson 2003).

Moreover, it supports the contention that the need for affiliation positively affects

team identification (Donavan, Carlson, and Zimmerman 2005). If team identification is defined as spectators perceived connectedness to a team (passionate

supporter) and its performance (positive support), in line with Gwinner and

Swanson (2003), then our results indicate that the level of team identification directly

and indirectly (through sponsor receptiveness and sponsor integrity) affects the

intention to purchase a sponsors products. This might prove an important

implication for point of sale marketing in sport clubs when considered in light of

Kwon and Armstrongs (2002) study, which revealed that team identification was the

only significant predictor of impulse merchandise purchasing.

The indirect effects are supported by data from Wann et al. (2001) who observed

that highly identified fans evaluate in-group members higher than out-group

members. Although it remains unclear if sponsors are counted towards the

membership of the in-group, this research has provided some suggestive evidence

that this may be a reasonable hypothesis. To be considered as part of the in-group is

also likely to be positively influenced by the duration of the sponsorship association;

the longer a sponsor supports the sponsored entity, the more likely it is that the

sponsor is considered to be part of the team.

Finally, sponsor integrity and sponsor receptiveness both play a substantial role in

promoting purchase intentions. As identified by Fink, Trail, and Anderson (2002),

Madrigal (2001), Murrell and Dietz (1992) and Wann and Brandscombe (1993), an

outcome of a strong psychological connection to a team is loyalty, and this

unconditional support is often expressed in consumption of team or club-related

products or services, continuing in both the good and bad times (James, Kolbe, and

Trail 2002). Receptiveness is about being listened to and if this is a well-communicated

and packaged sales message, then to listening to another loyal supporter of the team

its sincere sponsor is merely an expression of loyalty.

Journal of Marketing Communications

401

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

Conclusion

This research has examined key processes in the sponsorship relationship that influence

members purchase intentions toward the major sponsors products. Although a large

sample was employed, this study was limited by a low response rate, which suggests the

potential of a self-selection bias in regard to sponsorship opinions and attitudes. The

results also constitute a single case in a professional sporting league comprising 15 other

teams in one country. Therefore, it is reasonable to be cautious about projecting the

findings beyond the context of Australian professional football. Nevertheless, the

strength of the results is suggestive of some salient practical implications.

The argument made by Lachowetz et al. (2002) that sponsors should change their

focus from raw volume of exposure to image matching or fit has been strongly

supported by the outcomes of this research. Team support, sponsor receptiveness

and sponsor integrity are key components of the relationship that sponsors may

build with the members of the sponsored organization. All three variables contribute

significantly to higher purchase intentions.

The results reported here suggest that sponsor success can be amplified by

enhancing enthusiasm for the team. This has a positive impact on perceived integrity

and receptiveness, which are the primary factors influencing purchase intention. In

other words, in sport sponsorship it may be better for the sponsor to engage with the

club and its members, and encourage members to participate actively in club

activities. Generating passion and enthusiasm for the team may do more for

purchase intentions than targeting market segments in isolation from the broader

context of the club and its members.

Sponsors can also bolster the purchase intentions of club members by focusing on

strategies to strengthen perceived sponsor integrity. Compatibility with the sponsored

team, showing a genuine interest in the club and its supporters, supporting local

communities, and financial support for the team all contribute towards enhancing

sponsor integrity. Teams that already enjoy high levels of member support are more

likely to boast a customer base that is willing to consider sales offers from sponsors. The

level of sponsor integrity is therefore another criterion that can actively be manipulated

and managed by the sponsor. Future research might expand the approach presented

here by taking into account the level of exposure the sponsor receives and its associated

impact on purchase intentions. In addition, the introduction of behavioural measures

would be advantageous in explicating the connection between purchase intentions and

the actual consumption of sponsors products.

Notes on contributors

Aaron Smith and Hans Westerbeek are Professors in Sport Management at La Trobe

University in Melbourne, Australia.

Brian Graetz is a Professor in the School of Business at La Trobe University in Melbourne,

Australia.

References

Alwin, D., and R. Hauser. 1975. The decomposition of effects in path analysis. American

Sociological Review 40 (February): 3747.

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

402 A. Smith et al.

Ambler, T. 1998. Myths about the mind: Time to end some popular beliefs about how

advertising works. International Journal of Advertising 17, no. 4: 5019.

Ashill, N., J. Davies, and A. Joe. 2000. Consumer attitudes towards sponsorship: A study of a

national sports event in New Zealand. International Journal of Sports Marketing and

Sponsorship 2, no. 4: 291313.

Barry, T., and D. Howard. 1990. A review and critique of the hierarchy of effects in

advertising. International Journal of Advertising 9, no. 2: 12135.

Chadwick, S. 2002. The nature of commitment in sport sponsorship relations. International

Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship 4, no. 3: 25774.

Clark, J., T. Cornwell, and S.W. Pruitt. 2002. Corporate stadium sponsorships, signaling

theory, agency conflicts and shareholder wealth. Journal of Advertising Research 42,

no. 6: 1632.

Cornwell, T., G. Relyea, R. Irwin, and I. Maignan. 2000. Understanding long-term effects of

sports sponsorship: Role of experience, involvement, enthusiasm and clutter.

International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship 2, no. 2: 12743.

Daneshvary, R., and R. Schwer. 2000. The association endorsement and consumers intention

to purchase. Journal of Consumer Marketing 17, no. 3: 20313.

Donavan, D., B. Carlson, and M. Zimmerman. 2005. The influence of personality traits on

sports fan identification. Sport Marketing Quarterly 15, no. 1: 3142.

Farrelly, F., and P. Quester. 2003. The effects of market orientation on trust and commitment:

The case of the sponsorship business-to-business relationship. European Journal of

Marketing 37, nos. 34: 53053.

Ferrand, A., and M. Pages. 1996. Football supporter involvement: Explaining football match

loyalty. European Journal for Sport Management 3, no. 1: 720.

Fink, J., G. Trail, and D. Anderson. 2002. An examination of team identification: Which

motives are most salient to its existence? International Sports Journal 6, no. 2: 195207.

Grohs, R., U. Wagner, and S. Vsetecka. 2004. Assessing the effectiveness of sport

sponsorships: An empirical examination. Schmalenbach Business Review 56, no. 2:

11938.

Gwinner, K., and S. Swanson. 2003. A model of fan identification: Antecedents and

sponsorship outcomes. Journal of Services Marketing 17, no. 3: 27594.

Hoek, J., P. Gendall, and K. Theed. 1999. Sport sponsorship evaluation: A behavioural

analysis. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship 1, no. 4: 32844.

, and J. Sanders. 1993. Sponsorship management and evaluation: Are managers

assumptions justified? Journal of Promotion Management 1, no. 4: 5366.

Hughson, J. 1999. A tale of two tribes: Expressive fandom in Australias A-league. Culture,

Sport, Society 2, no. 3: 1130.

Irwin, R., T. Lachowetz, T. Cornwell, and J. Clark. 2003. Cause-related sport sponsorship: An

assessment of spectator beliefs, attitudes, and behavioral intentions. Sport Marketing

Quarterly 12, no. 3: 1319.

Jackson, S., R. Batty, and J. Scherer. 2001. Transnational sport marketing at the global/local

nexus: The adidasification of the New Zealand All Blacks. International Journal of

Sports Marketing and Sponsorship 3, no. 2: 185201.

James, J., R. Kolbe, and G. Trail. 2002. Psychological connection to a new sport team:

Building or maintaining the consumer base. Sport Marketing Quarterly 11, no. 4:

21525.

Jones, I. 2000. A model of serious leisure identification: The case of football fandom. Leisure

Studies 19: 28398.

Kline, R. 1998. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: The

Guilford Press.

Kwon, H., and K. Armstrong. 2002. Factors influencing impulse buying of sport team licensed

merchandise. Sport Marketing Quarterly 11, no. 3: 15164.

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

Journal of Marketing Communications

403

Lachowetz, T., M. McDonald, W. Sutton, and D. Hedrick. 2002. Corporate sales activities

and the retention of sponsors in the National Basketball Association (NBA). Sport

Marketing Quarterly 12, no. 1: 1826.

Lafferty, B., and R. Goldsmith. 1999. Corporate credibilitys role in consumers attitudes and

purchase intentions when a high versus a low credibility endorser is used in the ad.

Journal of Business Research 44, no. 2: 10916.

Lee, M., D. Sandler, and D. Shani. 1997. Attitudinal constructs towards sponsorship: Scale

development using three global sporting events. International Marketing Review 14, no. 3:

15969.

Levin, A., C. Joiner, and G. Cameron. 2001. The impact of sports sponsorship on consumers

brand attitudes and recall: The case of NASCAR fans. Journal of Current Issues and

Research in Advertising 23, no. 2: 2331.

Madrigal, R. 1995. Cognitive and affective determinants of fan satisfaction with sporting

event attendance. Journal of Leisure Research 27, no. 3: 20527.

. 2001. Social identity effects in a belief-attitude-intentions hierarchy: Implications for

corporate sponsorship. Psychology and Marketing 18, no. 2: 14565.

Meenaghan, T. 1991. Sponsorship legitimising the medium. European Journal of Marketing

25, no. 11: 510.

. 2001. Understanding sponsorship effects. Psychology and Marketing 18, no. 2:

95122.

, and P. OSullivan. 2001. The passionate embrace-consumer response to sponsorship.

Editorial. Psychology and Marketing 18, no. 2: 8794.

Miles, L. 2001. Successful sport sponsorship: Lessons from Association Football the role of

research. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship 2, no. 4: 35769.

Miyazaki, A., and A. Morgan. 2001. Assessing market value of event sponsoring: Corporate

Olympic sponsorships. Journal of Advertising Research 41, no. 1: 915.

Morris, D. 1981. The soccer tribe. London: Jonathan Cape.

Murrell, A., and B. Dietz. 1992. Fan support of sports teams: The effect of a common group

identity. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 14, no. 1: 2839.

Ohanian, R. 1991. The impact of celebrity spokespersons perceived image on consumers

intention to purchase. Journal of Advertising Research 3, no. 1: 4654.

Pope, N. 1998. Consumption values, sponsorship awareness, brand and product use. Journal

of Product and Brand Management 7, no. 2: 12436.

, and K. Voges. 2000. The impact of sport sponsorship activities, corporate image, and

prior use on consumer purchase intention. Sport Marketing Quarterly 9, no. 2: 96102.

Richardson, B., and E. ODwyer. 2003. Football supporters and football team brands: A

study in consumer brand loyalty. Irish Marketing Review 16, no. 1: 4353.

Roy, D., and T. Cornwell. 2003. Brand equitys influence on responses to event sponsorships.

Journal of Product and Brand Management 12, no. 6: 37793.

, and T. Graeff. 2003. Influences on consumer responses to winter Olympics

sponsorship. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship 4, no. 4: 35575.

Silvera, D., and B. Austad. 2004. Factors predicting the effectiveness of celebrity endorsement

advertisements. European Journal of Marketing 38, nos. 1112: 150926.

Speed, R., and P. Thompson. 2000. Determinants of sports sponsorship response. Journal of

the Academy of Marketing Science 28, no. 2: 22638.

Strong, E.K. 1925. The psychology of selling. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Tabachnick, B., and L. Fidell. 2001. Using multivariate statistics. 4th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Tapp, A. 2004. The loyalty of football fans well support you evermore? Journal of Database

Marketing and Customer Strategy Management 11, no. 3: 20315.

Tripp, C., T. Jensen, and L. Carlson. 1994. The effects of multiple product endorsements by

celebrities on consumers attitudes and intentions. Journal of Consumer Research 20,

no. 4: 53547.

Downloaded by [University of Bucharest ] at 11:24 08 March 2015

404 A. Smith et al.

Vakratsas, D., and T. Ambler. 1999. How advertising works: What do we really know?

Journal of Marketing 63, no. 1: 2643.

Verity, J. 2002. Maximising the marketing potential of sponsorship for global brands.

European Business Journal 4, no. 4: 16173.

Wann, D. 1995. Preliminary validation of the sport fan motivation scale. Journal of Sport and

Social Issues 19, no. 4: 37796.

, and F. Grieve. 2005. Biased evaluations of ingroup and outgroup spectator behavior

at sporting events: The importance of team identification and threats to social identity.

Journal of Social Psychology 145, no. 5: 53145.

, M. Melnick, G. Russell, and D. Pease. 2001. Sport fans: The psychology and social

impact of spectators. New York: Routledge.

, and N. Branscombe. 1993. Sports fans: Measuring degree of identification with their

team. International Journal of Sports Psychology 24, no. 1: 117.

Wiley, C., S. Shaw, and M. Havitz. 2000. Mens and womens involvement in sports: An

examination of the gendered aspects of leisure involvement. Leisure Sciences 22, no. 1:

1931.

You might also like

- Consum Behav When Eating OutDocument17 pagesConsum Behav When Eating OutDedeNo ratings yet

- Tempo Tur105d 24 5 2014Document2 pagesTempo Tur105d 24 5 2014DedeNo ratings yet

- Sosiri Ale Turistilor SUCEAVADocument2 pagesSosiri Ale Turistilor SUCEAVAalexandraaa210No ratings yet

- Articol StiintificDocument12 pagesArticol StiintificDedeNo ratings yet

- Advertising and Sales Promotion Course Book Kbs 2 DeanDocument21 pagesAdvertising and Sales Promotion Course Book Kbs 2 DeanDedeNo ratings yet

- Tsao Matthews CrittendenDocument11 pagesTsao Matthews CrittendenDedeNo ratings yet

- Recruit QuestDocument2 pagesRecruit QuestKamal Kannan GNo ratings yet

- Modele de MKDocument1 pageModele de MKDedeNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Florian1995, Mental HealthDocument9 pagesFlorian1995, Mental Healthade ubaidahNo ratings yet

- MSC StatisticsDocument36 pagesMSC StatisticsSilambu SilambarasanNo ratings yet

- Data Preparation and Analysis 3Document182 pagesData Preparation and Analysis 3Karishma AkhtarNo ratings yet

- Trustworthiness and Margins in Islamic Small Business Financing: Evidence From IndonesiaDocument12 pagesTrustworthiness and Margins in Islamic Small Business Financing: Evidence From IndonesiaAgus ArwaniNo ratings yet

- Facebook Self DisclosureDocument9 pagesFacebook Self DisclosureGianinaNo ratings yet

- Asessment BurnoutDocument10 pagesAsessment BurnoutSMA N 1 TOROHNo ratings yet

- A Sample Quantitative StudyDocument13 pagesA Sample Quantitative StudyAnonymousgirl150No ratings yet

- Comparing Shopper Typologies in Traditional Malls and Factory OutletsDocument10 pagesComparing Shopper Typologies in Traditional Malls and Factory OutletsPankaj SeekerNo ratings yet

- Factor Analysis: © Dr. Maher KhelifaDocument36 pagesFactor Analysis: © Dr. Maher KhelifaIoannis MilasNo ratings yet

- Creating and Validating An Information Quality ScaDocument28 pagesCreating and Validating An Information Quality Scazacharycorro14No ratings yet

- Statistical Data Analysis ExplainedDocument359 pagesStatistical Data Analysis Explainedmalikjunaid92% (24)

- Lab #2 - Descriptives: Statistics - Spring 2008Document16 pagesLab #2 - Descriptives: Statistics - Spring 2008Zohaib AhmedNo ratings yet

- Brand PersonalityDocument9 pagesBrand PersonalityYen Lee KuanNo ratings yet

- AvreDocument249 pagesAvreCikgu Manimaran KanayesanNo ratings yet

- How Positive Practices Impact Organizational EffectivenessDocument60 pagesHow Positive Practices Impact Organizational EffectivenessLorena BerberNo ratings yet

- 10 1108 - CG 11 2017 0271Document23 pages10 1108 - CG 11 2017 0271Ilham FajarNo ratings yet

- Frozen Food Industry in India Market StudyDocument24 pagesFrozen Food Industry in India Market StudyRishav sinhaNo ratings yet

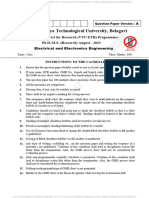

- Visvesvaraya Technological University, Belagavi: VTU-ETR Seat No.: ADocument64 pagesVisvesvaraya Technological University, Belagavi: VTU-ETR Seat No.: AMallikarjun NaregalNo ratings yet

- Business Research Methods Questions Paper PDFDocument24 pagesBusiness Research Methods Questions Paper PDFNisha pramanikNo ratings yet

- Service Quality Effects On Customer Satisfaction in Banking IndustryDocument8 pagesService Quality Effects On Customer Satisfaction in Banking Industryesmani84No ratings yet

- Antecedent of Loyalty AirlinesDocument14 pagesAntecedent of Loyalty AirlinesBeni BeneNo ratings yet

- 182911-Article Text-465782-1-10-20190201Document12 pages182911-Article Text-465782-1-10-20190201speedotNo ratings yet

- Principal Components Factor AnalysisDocument11 pagesPrincipal Components Factor AnalysisIrfan U ShahNo ratings yet

- Pertemuan 9Document34 pagesPertemuan 9Mala NingsihNo ratings yet

- 2011 Predictive Index Technical OverviewDocument21 pages2011 Predictive Index Technical OverviewSherman KasavalNo ratings yet

- Herding Pada Investor Saham Ritel Di Bursa Efek: Faktor-Faktor Yang Berkontribusi Terhadap Perilaku IndonesiaDocument23 pagesHerding Pada Investor Saham Ritel Di Bursa Efek: Faktor-Faktor Yang Berkontribusi Terhadap Perilaku Indonesiakakao pageNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behavior Toward Adoption of Mobile Payment A Case Study in Indonesia During The COVID 19 PandemicDocument10 pagesConsumer Behavior Toward Adoption of Mobile Payment A Case Study in Indonesia During The COVID 19 PandemicShowkatul IslamNo ratings yet

- TorranceDocument15 pagesTorranceGunesNo ratings yet

- Internship ReportDocument54 pagesInternship ReportMizanur RahamanNo ratings yet

- 1.phar OwnersipDocument12 pages1.phar OwnersipDesi DamayantiNo ratings yet