Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1 s2.0 0304422X81900309 Main

Uploaded by

Laura Leander WildeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1 s2.0 0304422X81900309 Main

Uploaded by

Laura Leander WildeCopyright:

Available Formats

Poetics 10 (1981) 109-126

North-Holland Publishing Company

109

INTRODUCTION

ON THE WHY, WHAT AND HOW OF GENERIC TAXONOMY *

MARIE-LAURE RYAN

The attitude toward the concept of genre which one fmds most pervasive in contemporary literary studies is a skepticism that conceals uneasiness and even discouragement. Reluctant to tackle a case that has been open since the beginnings of

their discipline, but never definitely resolved, literary critics invoke a number of

arguments to bring about its dismissal. One of the many excuses used to avoid wrestling with the problem of genre is that no consensus has ever been reached on a

definition of genre, and that, therefore, the concept is too hopelessly fuzzy to

achieve scientific respectability. The prospect for consensus does not look any

brighter on the level of individual generic categories than on the level of the family

concept: after some two thousand years of enquiry, not so much as one genre has

been completely defined (A. Dundes, quoted in Ben-Amos 1969: 175). To make

the matter worse, contemporary writers seem to be doing their best to prove the

notion obsolete. The popularity of the term text as replacement for traditional

generic labels betrays a desire among both critics and writers to deprogram the reading public by freeing the act of writing from any kind of convention. A fairly typical attitude among todays literary authors is to claim that when they write, they

do not care about genre. Why then should the critic attempt to put a label on their

works? Critics echo this objection by arguing that the truly great literary works are

those that break away from any established norm. After alI, it is said, it is common

knowledge that real genius cannot be harnessed by petty conventions. Those who

need the shelter of genre are mostly minor writers (cf: Corti 1978: 132), and why

should the critic bother with second-rate products, when he can exert his reading

skills on immortal masterpieces?

To the reader who endorses the view of poetics defended in this journal, none of

these constitutes a valid argument. Unlike the brand of criticism still prevalent in

academic circles, theoretical poetics is not primarily concerned with the masterpieces of world literature, but rather with the whole of the literary institution. It

* I am indepted to Bernard Rollin, Paul Hemadi and JOAM Schick-Baynum

upon the manuscript of this paper and offered stylistic advice.

Authors address: 5900 Birch, Bellvue, CO 80512, U.S.A.

0 304422X/8 l/0000-0000/$02.50

0 North-Holland

who commented

110

M-L. Ryan /Introduction

cannot therefore turn its back on those minor works whose production can be

traced back to a well-defiied generic recipe. The conscious struggle of avant-garde

writers against all attempts to classify their work does no more to challenge the

importance of genre in literary history than does the alleged uniqueness of the great

masterpieces. In trying to escape from the prison of genres, these writers bear

indirect witness to the power of that institution,

regardless of the success of their

attempts to break away. As to the alleged fuzziness of the individual generic categories, it only constitutes a drawback if these notions are used as analytical tools.

But if genres are an object rather than an instrument of investigation, if they are

more or less given entities themselves needing to be explained, then their fuzziness

will no longer constitute a theoretical shortcoming, but a fact to account for. That

fuzzy does not mean unworthy of rigorous investigation,

as commonly believed,

can be demonstrated by the existence of a fuzzy set theory and of a logic of fuzzy

predicates. What should not be allowed to remain fuzzy, however, is the notion of

genre as class of the individual generic classes, since, as we shall see below, genre

itself can only be an analytical notion.

Counterbalancing

the literary critics impatience with traditional generic concepts, more particularly with the too long established division of literature into the

triad epid/lyric/dramatic

is a trend in current poetics which promises to give new

life to the concept of genre: that of viewing the study of literature not as a selfenclosed discipline, but as part of a global theory of discourse. One of the postulates of discourse theory is that language is a diversified entity, a collection of rules

with varying ranges of applicability which divide discourse into distinct species.

Inasmuch as language use is always specialized, the concept of genre should not

only be used in the literary domain, but as Mary Pratt suggests in the present issue,

in all realms of discourse. This view is relatively new in English speaking countries,

but it has permeated genre studies for a number of years in Germany, for instance

in the work of Giilich and Raible (1972, 1977). Interest in textual linguistics

awakened much earlier in.Germany

than for instance in the United States, and textual linguistics cannot avoid facing the problem of text typology. Another dominant trend in literary theory, that of replacing it within a semiotic framework (i.e.

within a general theory of communication

and signification),

speaks in favor of

expanding the concept of genre even farther, so that it will also apply to forms

of deliberate human communication

relying on acoustic and visual media, or to

combinations of these with the linguistic code.

But whether the dividing lines of.genre are made to cut through the realm of

literature exclusively, or are extended toward all discourse or communication,

the

concept of genre will only receives firm theoretical basis if the investigator confronts the questions which underlie every taxonomical

enterprise: Why classify?

What is to be classified? How is one to classify? As long as these questions are

shunned, discourse about genre will not be theory, but simply criticism. What is

most urgently needed in the study of genre is not yet another way to justify traditional divisions, nor another ingenious way to divide literature, discourse, or com-

M.-L. Ryan /Introduction

111

munication, but, as B. Rollin points out in his contribution to this issue, an exploration of the logic underlying the very attempt to construct taxonomies of these

domains. In what follows I propose to give a general overview of the problems

facing genre theory, by breaking the why, what and how of generic taxonomy into

more specific and manageable questions.

1. Why classify?

Whether it seeks to establish an order among already given units, or creates these

units through the very act of drawing dividing lines across a certain field, every sig

nificant taxonomy must be supported by an explicit theory. The function of this

theory is either to account for the natural delineation of the units, or to justify the

choice of the proposed model over other possible ones. In biological classification,

the archetype of all taxonomies, the explanatory principle is genetic and historical.

Common ancestry decides which species may be grouped together on the tree of

life, and the possibility of breeding together decides which individuals may be

grouped under the same species. Inspired by the apparent success of biological

taxonomy, nineteenth century scientists attempted historical/genetic explanations

in a number of other fields. The work of Brunetiere stands as the classical attempt

to introduce evolutionary considerations into the study of genre:

Sans doute la differentiation des genres sopke-t-elle dans Ihistoire comme celle des espkes

dans la nature, progressivement, par transition de Iun au multiple . . 11sagit de savoir quel est

le rapport de ces formes entre elles, et les noms que Ion doit donner aus causes encore inconnues qui semblent les avoir dCgagCes les une des autres. (Quoted in Hempfer 1973: 202.)

For proponents of this approach, the answer to the question why is literature

divided into genres is tied to the answer to another question: where do genres

come from? One of the most recent attempts to define genres by means of a

genetic argument is Todorovs (1976) claim that genres derive historically from

speech acts such as lament, praise, or greeting. (This is not the same as saying that

genres incorporate speech acts among their ingredients!)

These evolutionary explanations appear as unsatisfactory as the recourse to

history to define the units of the linguistic code. What discredits historical/genetic

arguments in genre theory is that, as Rollin points out, literature (or discourse, or

communication) is in essence a matter of meaning, that is of signification. And

when it comes to explaining the functioning of signs, as Saussure has established,

their history becomes altogether irrelevant. Just as the speaker of English need not

be aware of the fact that th (6) is a reflex of Proto-Indo-European t, or that silZy

once meant blessed, the spectator of a greek comedy can participate in the communicative event without knowing that the genre originated (if Aristotle is right) in

phallic song and improvisation. Once we realize that genres are a matter of communication and signification, generic taxonomy becomes tied to the same type of

M-L. Ryan f Introduction

112

assumption that underlies current linguistic theories: namely that the object to

account for is the users knowledge. According to this assumption, the communicative competence. of the members of a culture includes a generic component,

through which they are able to handle a variety of linguistic artifacts such as tragedies, poems, jokes, and advertisements. The significance of generic categories thus

resides in their cognitive and cultural value, and the purpose of genre theory is to

lay out the implicit knowledge of the users of genres.

2. What classify?

The first decision to make when addressing the problem of getting at the basic units

of the proposed taxonomy, is whether these units exist independently of the taxonomical scheme, or arise as a result of the attempt to classify. These two possibilities correspond, respectively, to the philosophical stances of realism and nominalism (as discussed in Hempfer 1973), or to what B. Rollin (this issue) calls naturalism and conventionalism. Proponents of the conventionalist/nominalist position

hold that discourse, literature, or communication can be divided along a number of

different lines, and that the task facing the genre theorist is simply to find the most

useful way to draw the divisions. An example of a nominalist approach toward

literary taxonomy is the one advocated by Bennison Gray (1978: 144):

The initial question should be neither What are the kinds of literature, reully [my italics]?

Nor should it be: What do we actually mean when we talk about kinds or genres of literature. The proper question is: Can we conceive of a consistent literary taxonomy that in addition to providing a hierarchical system of either/or distinctions also provides a consistent correlation with some central feature of the subject?

The authors example of a classificatory scheme meeting these criteria is a tree

representing the various ways to present a narrative (see fig. 1). Like ail nominalist

taxonomies, this model avoids the labels in use among the readers, writers and

sellers of literature, in favor of a technical metalanguage for the exclusive use of the

literary scholar. But it leaves one wondering what central feature of the subject

can be explained by its categories. Since the nominalist denies the existence of

naturally given or predefmed units, he cannot present his model as an account of

the users awareness of already distinct discourse categories. Where then is he going

to find criteria of usefulness? Once we accept the assumption that genres have a

Literature

Unmediatnediated

A\

Monolog

Dialog

erial

Script

Fig. 1.

M-L. Ryan /Introduction

113

social and cognitive reality, we are pretty much committed to a compromise

between the conventionalist/nominalistic and the naturalistic/realistic approaches.

As divisions of verbal communication, genres are conventionally defined entities,

since they are man-made and not nature-made, and since there is more than one

way to divide the realm of verbal communication. Different cultures make indeed

use of widely differing systems of genres. But from the point of view of the investigator, genres are something given, something existing out there in the minds of

the members of a culture. The genre theorist deals with the species of culture, just

as the biologist deals with the species of nature.

One of the proponents of a compromise between the two stances is Dan BenAmos, who suggested in a pioneering article (1969) that genre theory should be

based on the generic labels in use in a given culture. He opposes the ethnic genres

yielded by native taxonomy to the analytical categories made up by the specialist

for their description and classification, and he warns against the danger of changing folk taxonomies, which are culture-bound and vary according to the speakers

cognitive system, into culture-free, analytical, unified and objective models of folk

literature (1969: 276). The discrepancy between ethnic and analytical categories may be somewhat blurred to students of Western folklore and literature,

since the analytical categories in use among specialists were presumably made up to

reflect the Western cultural reality, but it becomes obvious when the same categories are matched against the verbal tradition of a foreign culture.

Yet even if the generic system of every culture should be studied in its own

terms, there is no need to give up the possibility of describing its genres by means

of cross-culturally applicable concepts. The gap between ethnic and analytical

approaches to the problem of genre can be bridged by viewing analytical categories

as building blocks for the characterization of genres, rather than as abstract generic

concepts in themselves. The analytical categories underlying genre theory will then

be elements such as narrative, fictional, exemplary, free vs. bound in

form, etc., rather than myth, legend, riddle, efc. These cross-culturally

applicable categories may be used as the parameters of universal classificatory

schemes, such as in the model proposed by R. Champigny in the present issue [ 11.

The usefulness of these schemes resides in their ability to form the basis of crosscultural comparisons of genres, a task that would remain impossible if one dealt

exclusively with ethnic categories. Once abstract analytical features have regrouped

actual ethnic genres into broad families, however, we still need to differentiate the

[ 1] Another good example of a purely analytical classificatory model is that proposed by Longacre (1976). He divides discourse into narrative. procedural, behavioral, and expository, according to the pair of distinctive features + or - chronological sequence and + or

- agent orientation. Examples of actual ethnic genres fitting into the four divisions of this

model are novel and short story for narrative, recipes and how to books for procedureal,

eulogies and pep talks for behavioral, and news reports, scientific writing and essays for expository.

114

M-L. Ryan / Iwroduction

members of each group. It seems neither feasible, nor even desirable to perform this

task without resorting to culture-bound

categories. If one chooses to derive basic

units from native taxonomy, it would be very unreasonable to ignore the native

way of defining these units, which is likely to rely on culture-bound

concepts.

(Through etymology,

native labels often provide the key to native definitions.)

Susan Tripps analysis of Sanskrit genre theory provides a strong point in favor of

combining universal features with culture-specific

concepts in the description of

genres. Sanskrit drama, for instance, must be characterized in terms of rosa, a term

which captures the intended effect on the audience and cannot be divorced from

the social context, just as Greek tragedy must be defied by means of the highly

culture-bound

concept of catharsis.

The assumption that the elements of a genre theory can be directly derived from

native taxonomy is not itself without its own problems. First of all there is no such

thing as the native taxonomy. It would be simplistic to assume that a culture makes

use of only one set of labels, and that native taxonomy can therefore provide basic

units playing the same role as the species does in biological classification. Even if

the members of a culture agree on certain broad divisions of discourse, they will

base their taxonomy on various levels of abstraction, depending on their communicative needs. As Clark and Clark have pointed out (1978: 235) basic categories

vary with the experience of the people who name the objects. The most useful

level of distinction for a literary critic may comprise classes such as sonnet, ballad,

hymn, etc., but for the student who takes literature classes as part of the general

requirements

for a college degree, the modern version of the classical epic-lyricdramatic triad, namely novel, poem and play, is more than sufficient. If he chooses

to rely on the labels in use in a given culture, the genre theorist should therefore

give up the idea of a basic level of genre, in favor of a relativistic model of discourse taxonomy.

Another problem with native taxonomy, is that the communicative competence

of the members of a group may be more diversified than suggested by the labels

they use. For instance, Ben-Amos (1969) observes that the Limba of Sierra Leone

have only one term for their prose expression - mboro. This term seems to cover

such various prose forms as what we would call, somewhat ethnocentrically,

folktale, riddle, proverb, and historical accounts. Ben-Amos suggests, however, that the

Limba people differentiate

behaviorally, if not explicitly verbally, betweeen the

various forms of mboro. The short forms are used in the context of persuasion,

arguments, oratory, and joke, while the longer forms are told in the relaxed atmosphere of the evening before retiring. It can be argued that the complementary

distribution of the long and short mboro, and consequently

the fact that different

appropriateness

conditions relate to the two forms, constitutes sufficient ground

for viewing them as distinct genres. Under this proposal, the systematic clustering

of properties - here textual and contextual requirements - provides an elementary

discovery procedure for getting at the units of the system of genres. In the above

example, the discovery procedure refines native categories without disrupting them;

M-L. Ryan /Introduction

11.5

but there is no guarantee that the results yielded by this method will always be

compatible with the native taxonomy.

A third reason that native taxonomy fails to turn up directly the basic elements

of a genre theory, is that the metalinguistic vocabulary of a culture usually relates

to various aspects of verbal communication.

Among the 410 metalinguistic expressions found by Brian Stross (1974) in Tzeltal Maya, for instance, we find terms corresponding not only to what folklorists would call genres, but aiso dialects, registers, ways of speaking, styles, erc. (See Hymes 1974 for a review of these notions.)

Moreover, when folk taxonomy provides terms for classes of classes, these may

group together forms of discourse along lines entirely different from the above categories. For instance, according to Bauman (1978), the Chamula Indians divide discourse into ordinary speech, speech for people whose hearts are heated, and

pure speech, according to the analytically reconstrued criteria of increasing formalism, redundancy, and invariability. The first category is itself undivided (it corresponds to unmarked everyday speech), the second comprises ways of speaking

(speech for bad people, angry speech), speech situations (court speech),

verbal games, and a form we may call genre (political oratory), while the third

is mostly made up of elements classifiable as genres: Song, prayer, true

ancient narrative, jokes, proverbs, etc. But despite this approximative correspondance between genre and true speech, the Chamula system of verbal

behavior can be entirely described by means of native terms. If he resorts to the

concept of genre, the investigator introduces a foreign element in the native taxonomy. Yet the use of foreign analytical notions is indispensable,

if one wishes to

make cross-cultural comparisons and work toward a general theory of literature,

discourse, and communication.

As a cross-culturally

applicable analytical concept, genre must be disentangled

from a number of competing notions pertaining to discourse. A way of dividing

discourse can be considered theoretically

relevant if it fulfdls either one of these

two criteria: (1) more than one predictable formal, semantic or pragmatic features

is paired with the proposed category; or (2) the category must be recognized as

such for proper communication.

These two ways to justify divisions of discourse

are illustrated, respectively, by baby talk and irony. Baby talk is not only discourse

addressed to a baby (pragmatic feature), it is characterized by a number of formal

particularities

in syntax, lexicon and phonology. The pragmatic category of irony

does not pair up with any other regular features in form or content, but a failure to

recognize a statement as ironic would lead to the failure of the communicative

event. Distinctions

of these two types can be found to occur in the following

rubrics (the list is far from exhaustive!):

Register: Mens speech VS. womens speech in cultures making this formal distinction; baby talk; legal jargon; written vs. oral style, etc.

speech situarion: Informal gathering, telephone communication,

sports broadcast,

court testimony, church service, etc.

116

M.-L. Ryan /Introduction

Speech event (the actual verbal exchange occurring in the above situations): conversation, telephone dialogue, play-by-play report, testimony, sermon.

Speech acts: assertion, question, command, praise, lament, promise, confession,

description, summary, etc.

Verbal modufities (i.e. types of intent, contrasting with the unmarked case of

speaking sincerely, seriously, and literally): metaphor, symbolism, imitation, lie,

fiction, irony, etc.

Verbal games and speech play: counting rhymes, pig latin, verbal duelling, riddles,

cross-word puzzles, etc.

To distinguish genre from the above notions we need first to ask: of what is genre a

type? (It makes sense to speak of types of speech acts, speech events, verbal games,

ect., but not of types of genre since genre itself means type!) The theoretical relevance of the concept of genre thus depends on whether or not, once we have gone

through this tentative list of speech notions, there is stilI a candidate left to fill in

Conspicuously missing

the empty slot in the expression genre is a type of -.

in the above repertory, is a class pertaining to the notion of text. If text itself is of

theoretical importance,

if it needs distinguishing

from discourse in general, discourse theory will need the concept of genre to regroup its varieties.

But what, in turn, is text? Despite the considerable amount of attention

devoted in recent years to text grammar and theory, linguists and literary critics

have too often been confronted with approximative defmitions, such as this one,

proposed years ago by Weinrich (1973: 13): A text is a meaningful sequence of

linguistic signs between two breaks of communication.

Since all verbal interaction

fulfills this condition (communicative

events always begin and end with silence),

Weinrichs definition fails to answer the theoretical need for distinguishing texts as

utterances composed according to a general plan and governed by global conditions

of coherence (what T.A. van Dijk (1977) would call a macro-structure),

from direction-switching

forms of verbal expression governed only by micro-level constraints.

Unlike the more general concept of discourse, which may apply to open-ended

utterances, text is a self-contained

entity whose ending cannot be dictated by an

external event. When rain interrupts a non-textual form of discourse, such as a conversation, the already exchanged words still qualify as conversation, but when the

death of the author interrupts the writing of a text such as novel or essay, what

remains is a fragment of novel or essay, a discourse but not a text. Another condition for a sequence of linguistic signs to constitute a text, I would suggest, is that its

unity must be brought to light through some framing device. Frames can be provided by titles and blank spaces, by introductory

and concluding formulae (do

you know the one about as a way to introduce a joke, dixi as a way to conclude

a public speech in the antiquity), by non-formulaistic

introductory and concluding

remarks (to illustrate this point I will tell you a story; this story tells US

that . . .); or simply by the material object through which the text is transmitted

(book for a novel, billboard for an advertisement).

These framing devices make

M.-L. Ryan / Irrtroduction

117

texts potentially detachable from a verbal context, a phenomenon

that Weinrichs

definition would disallow, text corresponding

for him to the entire exchange,

or if change of speaker counts as break in communication,

to the entire turn of a

single speaker. Texts may thus appear in the context of a non-textual speech event

(a joke told in a conversation, a tall tale during a drinking party), or may be part of

another text (a parable in a sermon, an anecdote in a political speech). It seems in

fact that anecdotes and parables cannot be used in any way other than embedded in

a verbal context. This would make texts self-contained

and detachable, but not

necessarily independent as a discourse unit.

Once we define genre as a type of text, its relationship to the above categories

becomes much less problematic. Since speech events may or may not involve the

transmission of a textual utterance, genre and speech event will sometimes fall

together (sermon, political speech) and sometimes remain distinct (interview, chatting, telephone conversation).

The notion of speech situation pairs up with the

notion of genre whenever a type of text is used on a specific occasion, such as a sermon during church services and a toast during a banquet. Pragmatic rules are then

needed to hook up the genre with the speech situation. The relationship between

types of texts and types of verbal games is one of overlap: some verbal games make

use of texts (counting rhymes, riddles), while others consist of open-ended discourse (verbal duelling, speaking in pig latin). And finally registers, speech acts and

verbal modalities relate to genre as possible ingredients: texts of a given genre may

require a specific register (legal jargon in laws), count as a specific speech act (question/answer in riddles), or involve a specific modality (fiction in novels, imitation in

pastiches, irony in satire). These remarks on the situation of genre within discourse

theory, and on the role of other discourse notions within genre theory remain of

course very sketchy. Any advance in the investigation of these domains will require

a sharpening, not only of the concepts of genre and text, but of the whole array of

rival discourse notions.

3. How classify?

Once a decision has been made as to how to retrieve the elements of a genre theory,

the next problem to be addressed is: what to do with these units? How genres

should be described and classified depends, primarily, on what type of sets they

constitute. Three possibilities must be taken into consideration. First of all generic

labels could belong to the same semantic category as geometrical predicates such as

round or square. These predicates are either entirely true or false of an object, and

the set they define draws a clear-cut line between members and non-members. If

generic labels belong to this type of predicates, each genre will be defined by a hard

core of necessary and sufficient conditions, and there wilI be almost unanimous

agreement among the members of a culture as to which texts belong to which category.

118

M-L. Ryan / introduction

The second possibility is that generic labels are fuzzy predicates. According to

logicians, a fuzzy predicate is one whose truth or falsity is relative to some standard

and is, therefore, a matter of degree. Small, rich, heavy fit in this category.

If genre labels are fuzzy predicates, each generic category will comprise highly typical and less typical members. Unlike the first possibility this view is compatible

with disagreements among the users of generic labels. But these disagreements will

not entail a lack of consensus over the genres definition. Just as we all know what

tall means, but may disagree as to whether or not such and such can be described as

tall, so we may share a definition of the tragic, but disagree when it comes to calling

a certain play a tragedy.

A third possibility is that generic categories constitute what Wittgenstein would

call family-resemblance

notions. Under this proposal, each genre would be associated - as Mary Pratt suggests in her contribution

-with a group of characteristics, only some of which may be present in a given member of the genre. Once

again, there would be highly typical and less typical members of every genre, but

the less typical ones would differ qualitatively and in a variety of different ways

from the most typical ones, rather than quantitatively

along a single dimension.

This proposal would explain disagreements among the users of generic labels in the

same way a semantic theory might explain possible variations in the use of such

familiar terms as table or chair. You and I may roughly agree as to which set of

properties it takes for an object to qualify as table or as chair, yet upon encountering a strange object presenting only some of the required properties you may label

it table or chair, while I prefer another term. This approach invites us to think of

genres as clubs imposing a certain number of conditions for membership, but tolerating as quasi-members those individuals who can fulfill only some of the requirements, and who do not seem to fit into any other club. As these quasi-members

become more numerous, the conditions for admission may be modified, so that

they, too, will become full members. Once admitted to the club, however, a member remains a member, even if he cannot satisfy the new rules of admission.

Which one of these three proposals is the most adequate? There is no compelling

theoretical reason to give a global answer to this question, and no methodological

need to fit all genres within the same model. For practical genres such as law, advertisement or recipe, the first approach is the most satisfying. What could one do with

a quasi law or a quasi recipe? These genres fulfill a narrowly defined purpose, and

there is widespread agreement as to which texts qualify as members. In the literary

domain, such consensus is only found in the case of purely formal genres such as

sonnets or haikus. Among the genres that seem to benefit from the second approach

are those which are supposed to arouse a certain emotion on the continuum of

human feelings, such as the drama kinds classified in Hernadis contribution,

or

those which embody a specific spirit or Weltatmhauuttg. By maintaining

that

poems can be more or less lyric, novels more or less epic, and plays more or less

dramatic depending on how strongly they embody the corresponding spirit, a critic

like Emil Staiger (1963) implicitly views the genres of the classical triad as fuzzy

M-L. Ryan /Introduction

119

sets, and their labels as fuzzy predicates. But in the majority of modern literary

genres, for instance in short stories, science fiction, detective novels, or simply

novels, borderline cases differ in so many different ways from the archetypes that

the model to be preferred is that of family-resemblance

notion. This model appears

particularly well suited to deal with the fact that genres evolve in time, and that

consumers recognize as members of the same class both currently produced texts

and works of older periods which are still readable, but no longer produceable.

The next problem to be taken into consideration,

is whether a genre theory

should take the form of a systematic taxonomy or of an informal catalog. The difference between these two types of classification resides in the availability of a

spatial model of organization. In a systematic taxonomy, to describe a unit is to

assign it to a predefmed slot on a twodimensional

network of relations, a slot

which reflects the properties of this unit. In an informal catalog, on the other hand,

newly described units are simply added to a one-dimensional,

open-ended inventory

without internal structuring principles. Classical examples of systematic taxonomies

are the periodic table of elements, where contiguous units present similarities in

atomic structure, and biological classification, where the place assigned to a species

on the tree of life reveals its genetic relations with other forms of life. As an

example of an informal catalog, one can mention the first contributions

to speech

act theory, which were more concerned with the enumeration and individual definition of various kinds of speech acts, than with the elaboration of some global

scheme of classification. Since spatial patterns represent a classificatory logic, systematic taxonomies enjoy far greater theoretical prestige than simple inventories.

This prestige explains the repeated attempts, by linguists, to organize the phonological inventories of languages along axes of symmetry, or the recent efforts of

speech act theorists (ex. Searle 1973) to regroup speech acts into broad families,

and to distinguish these by means of binary features. The feeling that a spatial, and

preferably symmetrical model of classification spells the difference between purely

descriptive and theoretical discourse has been particularly influential in the study

of genre, both in its purely literary and folklore-oriented

branches. In the present

issue, the spatial/relational

approach to genre classification is illustrated by the

Sanskrit genre theories discussed by Susan Tripp, and by Paul Hernadis mapping of

dramatic literature. The oppositie view - that differences between types of texts

present too much variety to justify a symmetrical spatial model of organization is defended by Mary Pratt. She argues that symmetrical classifications, such as

those obtained by binary features, presuppose that all elements of the system are

related and differentiated from each other in always the same ways. This assumption would lead the investigator not only to construct what G. Genette (1977) has

called fake windows to restore the symmetry when no genre seems to fit in a specific slot [2], but also to ignore those questions which are not relevant to all textual

types. It is clear for instance that literary genres require a different approach, and

[ 2 J An example of a classificatory scheme requiring some rather arbitrary decisions to preserve

M-L. Ryan /Introduction

120

call for different criteria, than purely practical genres. But if, all taken together, the

genres of a culture resist classification on a tree, wheel, pyramid, or whatever figure

one may think of, there is no reason to exclude the possibility for the general catalog of genres to include self-enclosed sub-systems characterized by systematic oppositions. We may not gain anything by construing a global spatial model for the classification of such heterogenous genres as riddle, obituary, and essays in literary

criticism, and by defiiing these genres in terms of each other; but within a homogenous, well-defined sub-system such as narrative fiction or drama, relational

analysis through contrasting features has often proved an effective method. Pratts

own account of the short story in terms of its opposition with the novel demonstrates the fruitfulness of a systematic approach, once adjusted to an object of reasonable size.

Rule types

The kind of principles involved in the characterization

of genres depends on

whether this characterization

is thought of as a maximally economical definition, or

as a maximally complete description of the genre. In some areas of language studies,

most notably in phonology, the users competence is better accounted for through

the economy of definition than through the wealth of description. Since all that is

needed to use a phoneme correctly is the ability to distinguish it from the other

phonemes of the language, the characterization

of the speakers phonological competence should not go beyond those principles needed to differentiate unambiguously the various members of the phonological system. But, as Pratt and Rollin

argue, such a restriction in genre theory would reduce it to the most trivial observations. If one followed the phonological model, all that genre theory would need

to say about the short story would be something like written-narrative-iictionalshort-pleasure-oriented

(or ludic, in Champignys terminology). This characterization correctly differentiates

the short story from any other text type, but - as

Pratts article demonstrates - it leaves aside the most interesting components of the

public knowledge and public habits pertaining to that genre. What makes this sort

of characterization

insufficient

is that competence,

in textual matters, goes far

its symmetry is the discourse taxonomy proposed by Charles Morris (1971: 203):

Mode

Designative

Appreciative

Prescriptive

Formative

Usage

Informative

Evaluative

Incitative

Systematic

Scientific

Mythical

Technological

Logico-mathematical

Fictive

Poetic

Political

Rhetorical

Legal

Moral

Religious

Grammatical

Cosmological

Critical

Propagandist

Metaphysical

M-L. Ryan /Introduction

121

beyond the mere ability to distinguish a type from another. Generic competence

differs from phonological competence in that it is subject to gradations: one cannot

use the phoneme t more or less well, one just uses it (even if the pronunciation is

poor), but one can show various degrees of expertise in dealing with a certain text

type. This would be a trivial observation, without consequences for genre theory, if

generic expertise were simply a matter of private knowledge and of individual

talent. But being good at using a genre is also a matter of cultural knowledge that is of a knowledge which must be shared in order to be efficient. To be an

expert at decoding advertisements, one must for instance be familiar with the usual

tricks of the genre so as to protect oneself from false conclusions; and to be successful at joke-telling one must know how to highlight the punchline through recognizable signals. While paying due attention to strictly distinctive features, genre theory

should thus remain open to whatever expectations the members of a culture associate with a genre, and to whatever uniformities can be observed in their behavior

when dealing with that genre.

This stance commits the genre theorist to a flexible approach to what I shall call

genre-sensitive regularities. One of the areas of genre theory where the most work

remains to be done is the exploration of the variety of principles involved in the differentiation of discourse into textual types. Neither current linguistic theories, nor

the greater part of literary semiotics have much help to offer to the genre theorist

seeking to refine his conceptual tools and to make explicit the theoretical status

of his observations. While linguistics (more particularly transformational grammar)

tends to ignore the facts that cannot be accounted for by means of rigid either/or

principles drawing an absolute line between legal and illegal constructs, literary

semiotics is plagued by an indiscriminate use of the terms code and convention.

Both disciplines thus blind themselves to the variety of species to be found among

the regularities pertaining to their object. A sorely needed semiotic enterprise, from

which not only discourse studies but all scientific disciplines would greatly benefit,

would be a typology of the regularities which may form the concern of scientific

discourse, based on an analysis of the various possible sources of uniform behavior

(such as: material causality, social contract, convention, habit, and confirmism).

(See Lewis 1969 for an important contribution to this future typology.) In genre

theory, the regularities involved in the differentiation of types include not only

imperative rules, but also options, tendencies, technical advice (that is, a rhetoric),

and rather loose guidelines for appropriate use.

A useful starting point, for the investigator trying to cut his way through the

jungle of genre-sensitive regularities, is Searles (1969) distinction between constitutive and regulative rules. The former define and create a form of behavior, while

the latter merely capture the regularities presented by an independently existing

activity. The regulative department of genre theory contains room for a wealth of

observation which specialists have too often swept under the rug, finding no place

for them in their analytical models. Among such observations one can mention:

that a good way to introduce a joke in a conversation is by means of the quasi-for-

122

M.-L. Ryan / Ituroductbn

mula you know the one about; that detective novels should avoid lengthy disgressions, or that redundancies are appropriate in fairy tales but unwelcome in news

reports. (A good source of regulative principles are the how to books for prospective writers of a given genre.) The non-authoritative,

flexible character of the regulative rules of genres invites their assimilation to the type of regularity which David

Lewis defies as convention.

With proper adaptation to genre theory, this definition reads as follows [3] :

A is

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

a convention (regulative rule) of genre x if:

Almost every sender of texts belonging to genre x conforms to A ;

Almost every receiver expects every sender to conform to A;

Almost every receiver would prefer every sender to conform to A;

A is not necessary, since sender and receiver could have agreed on another principle meeting the above conditions.

This definition,

it will be noted, takes care of sender-oriented

conventions. To

account for receiver-oriented

regularities (such as the reading conventions defined

in Steinmanns contribution),

it must be rewritten as follows:

(1) Almost every receiver conforms to A;

(2) Almost every sender expects almost every receiver to conform to A; erc,

It is the above distinction between two functions of generic principles which permits apparently

unproblematic

comparative statements such as: The narrative

style of myth welcomes digressions and ornate language in the Shoshone culture,

while it advocates sobriety of expression in the Yokuts culture (observations borrowed from Shin&in and from Newman and Gayton, both in Hymes 1964). While

Yokuts and Shoshone myths differ in their regulative conventions, they are classified in the same cross-cultural category by virtue of an alleged common core of constitutive features.

In addition to regulative and constitutive

principles, the description of genres

[3] The original version reads as follows (1969: 63):

A regularity (R) in the behavior of a population (P) when they are agents in a recurring situation (S) is a convention if and only if, in any instance of(S) among members of (fl:

(1) Everyone [or almost everyone] conforms to (R)

(2) Everyone expects [almost] everyone else to conform to (R)

(3) Everyone prefers to conform to (R) on the condition that the others do, since (S) is a

coordination problem and uniform conformity to (R) is a coordination equilibrium in

(s).

The distinction between sender and receiver in linguistic matters, and the existence of both

sender and receiver-oriented conventions, makes it necessary to modify this definition.

M-L. Ryan /Introduction

123

may finally include regularities which do not derive from rules, but rather from cultural and mental habits. Many sociological and cognitive facts belong to this category. There is for instance no principle qualifying as either constitutive rule or as

convention (as defined above) that instructs prospective writers of novels to first

try their hand at the short story: the success of this practice does not depend on a

similar behavior by other writers. And there is certainly nothing in the codification

of the novel that tells readers to pay less attention to details of micro-structure (surface form), and more attention to the semantic macro-structure,

than they would

when reading a poem. Most authors of non-popular novelistic genres would like

their readers to process their works as carefully as a poem on the micro-level. The

widely attested practice of focusing on units of different levels in novels and poetry

is due mostly to a material cause: the limitations of human memory, which call for

different strategies when processing long and short texts. Yet from a length-conditioned strategy, the procedure has evolved into a genre-conditioned

one, since long

poems are processed more or less like short ones, and short novels like long works

of the same genre. Even though their status as rules or conventions remains questionable, observations of these two types have a legitimate place in genre theory, if

the ambition of the theory is to account not only for the implicit knowledge, but

also for the actual behavior of the users of genres.

***

The diversity of the contributions

gathered in this issue is meant to be taken as a

plea in favor of a flexible and truly interdisciplinary

approach to the problem of

genre. The editorial policy was not to promote a unified methodology, but rather

to give the reader an idea of the many directions in which the study of genre or discourse types may be fruitfully pursued. Among the fields represented in the collection are: philosophy of taxonomy (Rollin), philosophy of language (Champigny),

sociology of literature (Pratt), cognitive psychology (Olson, Mark and Duffy),

speech act theory (Hancher), sign theory (Steinmann),

history of literary theory

(Tripp), and model logic and ontology (Pavel). A contact with the Western tradition

of literary criticism is nevertheless maintained through Hernadis essay.

The collection opens with the contributions

of two devils advocates: first

Bernard Rollin, who stresses the lack of theoretical foundations

for most of the

available literature on the question of genre, and urges the investigator to make

more explicit what he is looking for; and second Robert Champigny, who, after

outlining a semantically based, purely analytical scheme for the classification of discourse, goes on to discuss the merging, in modern literature, of the traditional

genres of poetry, novel and essay toward an amorphous species which he calls prose

poem, but in which one may also recognize the fashionable artifact commonly

labelled as text.

The third of the papers, Mary Pratts contrastive study of the novel and short

story, demonstrates that a purely formal analysis of text-internal features cannot do

124

M.-L. Ryan /Introduction

justice to the complexity of the phenomenon of genre. By detailing the wealth of

semantic and pragmatic differences that cluster around the opposition between long

and short forms in narrative pleasure fiction, she provides evidence supporting this

observation, originally made by Ben-Amos concerning two genres of Yoruba storytelling: There is a whole gamut of distinctions between these two genres, and

although the reduction of the difference to just a single set of contrastive attributes

may be analytically convenient, it is ethnographically simplistic (1969: 292).

If Pratts account of the short story is mostly writer-oriented, Hernadi adopts

the point of view of the audience in his classification of dramatic literature. He justifies this choice by arguing that our public reaction to performed plays is more

observable and less idiosyncratic than our private reaction to written or printed

texts. Through his mapping of individual works along the continuum of emotional

responses that they elicit from the audience, he generalizes the Aristotelian

approach to tragedy as applicable to all types of drama or perhaps even to nondramatic literature. Implicit in this procedure is the view that genres are archetypes

to which individual works do not belong in the strict sense, but rather in which,

as Staiger (1963: 241) and Derrida (1980: 18s) suggest, they participate to a

greater or lesser extent. By allowing an individual work to participate in several

types, this view appears particularly well suited to deal with the phenomenon of

mixed and hybrid genres. An excursion into one of the very few non-Western

theoretical reflections of genre is provided by Susan Tripps overview of Sanskrit

literature and Sanskrit genre theory. To the reader who wonders to which extent

Western preoccupations with genres are indebted to the_ Aristotelian heritage,

her article demonstrates very similar concerns in a totally foreign scholarly tradition.

Thomas Pavels analysis of myth and tragedy in terms of their underlying world

view innovates both in method and content previous attempts to define these two

genres; in method, by resorting to model logic and possible world semantics to

describe the structure of their respective ontological foundations; and, in content,

by insisting on the non-fictional character of mythical discourse. Not only is myth

to be opposed to the false discourse of fiction (false only literally, since fiction

may present an exemplary value), but also to alI genres of informative discourse

referring tothe states of affairs of the profane layer of the actual world. While the

accuracy or exemplary value of informative and fictional discourse may be called

into question, myth is rooted in a sacred reality from which it derives an absolute

authority. Two semantic classes of discourse thus emerge from Pavels discussion:

those of debatable and of guaranteed validity. He ascribes the birth of tragedy to

the disappearance of the sacred dimension from a cultures ontology. This disappearance deprives myth of a referent, and makes its narrative content available for

fictional communicatioh.

The common concern of the last three papers is with the diversification of interpretive strategies along the lines of genres. An approach which has enjoyed considerable popularity since the rise of literary semiotics consists of viewing genres as

M-L. Ryan /Introduction

125

programs for decoding (Corti 1978) or as systems of reading conventions

(CulIer 1975). Yet the results of this approach have been so far mostly trivial.

Martin Steinmanns essay is one of the very few serious attempts to convert the

vague notion of reading convention into concrete proposals. With his superordinate genre conventions he proposes various amendments to the general interpretive principle according to which the world of a fictional text is reconstructed as

being the closest possible to the reality we know (see Lewis 1978 on this principle,

and my own adaptation of it in Ryan 1980). Steinmann shows that some communicative demands such as exposition and plot development may create a conflict with

the demands of verisimilitude. The reader adjusts to this situation by bringing into

play a number of genre-sensitive conventions which override the criteria he would

normally use in the reconstruction and evaluation of the worlds of both fictional

and non-fictional texts. If discourse falls into genres, so does the meta-discourse

that relates to these genres. A genre theory should therefore be supported by a

theory of textual interpretation. Michael Hancher takes care of this problem, first

by situating interpretation within the framework of speech act theory, and second

by distinguishing various types of interpretive discourse, as they relate to various

types of texts. Moreover, by exploring a notion that can be viewed as either a

speech act, a speech act family, a genre, or a genre family, he invites the reader to

reconsider the problematic relations between the units of speech act theory and

text taxonomy. To conclude the colIection, Olson, Mack and Duffy tackle the

problem of interpretation at its most basic level, by exploring the possibility of an

empirical verification of the claim that genres have a primary psychological reality,

and that generic distinction affect elementary cognitive processes such as information storing and retrieval They focus on two possible factors in the diversification

of cognitive processes: first the generic distinction between essays and stories; and

second the distinction between ill-formed and well-formed texts within each of

these two genres.

Taken together, it is hoped that the papers gathered in this issue will demonstrate that genre theory can very welI live with the condition diagnosed by Dundes

- namely that not so much as one genre has been [or ever will be] completely

defined. That genres are not the sort of entities that can be given an exhaustive

and definitive defmition does not mean that they cannot form the object of a systematic and rigorous branch of knowledge presenting significant implications for

our understanding of human communication.

References

Bauman, Richard. 1978. Verbal art as performance. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Ben-Amos, Dan. 1969. Analytical categories and ethnic genres. Genre 2: 275-301.

Clark, Eve V. and Herbert H. Clark. 1978. Universals, relations, and language processing. In:

J. Greenberg, ed. pp. 255-278.

126

M-L.

Ryan /Introduction

Corti, Maria. 1978. An introduction to literary semiotics. Bloomington, IN: Indiana UP.

Culler, Jonathan. 1975. Structuralist poetics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP.

Derrida, Jacques. 1980. La loi du genre. Glyph 7: 176-232.

van Dijk, Teun A. 1977. Text and context: csplorations in the semantics and pragmatics of

discourse. London: Longman.

van Dijk, Teun A. 1979. Cognitive processing of literary discourse. Poetics Today I (2): 137160.

van Dijk, Teun A. 1980. Story comprehension: an introduction. Poetics 9: l-2 1.

Dressier, Wolfgang, ed. 1978. Current trends in text linguistics. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Fowler, Roger. 1979. Preliminaries to a socioloinguistic theory of literary discourse. Poetics 8:

531-556.

Genette,GCrard. 1977. Genres, types, modes. Podtique 32.

Gossen, Gary. 1978. Chamulagenres of verbal behavior. In: R. Bauman, ed. pp. 81-l 16.

Gray, Bennison, 1978. The semiotics of taxomomy. Semiotica 22: 127-149.

Greenberg, Joseph, ed. 1978. Universals of human languages 1: method and theory. Stanford,

CA: Stanford UP.

Giilich, Elisabeth and Wolfgang Raible, eds. 1972. Testsorten: Differenzierungskriterien

aus

linguistischer Sicht. Frankfurt: Athenatim.

Giilich, Elisabeth and Wolfgang Raible. 1977. Textmodelle: Grundlagen und Moglichkeiten.

Miinchen: Fink.

Hempfer, Klaus. 1973. Gattungstheorie. Miinchen: Wilhelm Fink.

Hymes, Dell, ed. 1964. Language in culture and society. New York: Harper and Row.

Hymes, Dell. 1974. Foundations of sociolinguistics: an ethnographic approach. Philadelphia,

PA: Pennsylvania UP.

Lewis, David. 1969. Convention: a philosophical study. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP.

Lewis, David. 1978. Truth in fiction. American Philosophical Quarterly 15: 34-46.

Longacre. Robert. 1976. An anatomy of speech notions. PDR Press publications in tagmemics,

No. 3.

Morris, Charles. 1971. Writings on the general theory of signs. The Hague: Mouton.

Newman, Stanley and Ann Gayton. 1940. Yokuts narrative style. In: D. Hymes, ed. pp. 272380.

Rogers, A., B. Wall and J.P. Murphy, eds. 1977. Proceedings of the Texas conference on performatives, presuppositions, and implicatures. Arlington, VA: Center for Applied Linguistics.

Ryan, Marie-Lame. 1979. Toward a competence theory of genre. Poetics 8: 307-337.

Ryan, Marie-Laure. 1980. Fiction, non-factuals, and the principle of minimal departure. Poetics

9: 403-422.

Schmidt, Siegfried. 1978. Some problems of communicative text theories. In: W. Dressier, ed.

pp. 47 -60.

Searle, John. 1969. Speech acts. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge UP.

Searle, John. 1973. A classification of speech acts. In: A. Rogers, B. Wall and J.P. Murphy,

eds., 1977. pp. 27-46.

Sherzer, Joel and Richard Bauman, eds. 1974. Explorations in the ethnography of speaking.

Cambridge, MA: Cambridge UP.

Shimkin, Dmitri. 1947. On Wind River Shoshone literary forms: an introduction. In: D.

Hymes, ed., 1964. pp. 344-355.

Staiger, Emil. 1963. Grunbegriffe der Poetik. Zurich: Atlantis.

Stross, Brian. 1974. Speaking of speaking: Tenejapa Tzeltal meta-linguistics. In: J. Sherzer and

R. Bauman, eds. pp. 213-239.

Todorov, Tzvetan. 1976. The origin of genres. New Literary History 8: 159-170.

Weinrich, Harald. 1973. Le temps. Paris: Seuil.

You might also like

- Fictional Worlds - Thomas G. PavelDocument97 pagesFictional Worlds - Thomas G. PavelSerbanCorneliu100% (8)

- PLETT Heinrich. IntertextualityDocument139 pagesPLETT Heinrich. IntertextualityVladimirMontana100% (14)

- Lodge - Analysis and Interpretation of The Realist TextDocument19 pagesLodge - Analysis and Interpretation of The Realist TextHumano Ser0% (1)

- Stanley Rosen The Elusiveness of The Ordinary Studies in The Possibility of Philosophy 2Document336 pagesStanley Rosen The Elusiveness of The Ordinary Studies in The Possibility of Philosophy 2alexandrospatramanis100% (1)

- MundosFiccionais Pavel PDFDocument97 pagesMundosFiccionais Pavel PDFPatricia PratesNo ratings yet

- Health Problem Family Nusing Problem Goals of Care Objectives of CareDocument8 pagesHealth Problem Family Nusing Problem Goals of Care Objectives of CareMyrshaida IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Gesture and Speech Andre Leroi-GourhanDocument451 pagesGesture and Speech Andre Leroi-GourhanFerda Nur Demirci100% (2)

- Ritual 2 Turning Attraction Into LoveDocument2 pagesRitual 2 Turning Attraction Into Lovekrlup0% (1)

- Culler-Lyric History and GenreDocument22 pagesCuller-Lyric History and GenreabsentkernelNo ratings yet

- Ulf+Lvwru/Dqg Hquh: New Literary History, Volume 40, Number 4, Autumn 2009, Pp. 879-899 (Article)Document22 pagesUlf+Lvwru/Dqg Hquh: New Literary History, Volume 40, Number 4, Autumn 2009, Pp. 879-899 (Article)NatrepNo ratings yet

- Lyric History and GenreDocument23 pagesLyric History and GenrePiyush K VermaNo ratings yet

- Race, Reason, and Cultural Difference in The Work of Emmanuel EzeDocument19 pagesRace, Reason, and Cultural Difference in The Work of Emmanuel EzemantiszopiloteNo ratings yet

- Giovanni Bottiroli - Return To Literature. A Manifesto in Favour of Theory and Against Methodologically Reactionary Studies (Cultural Studies Etc.)Document37 pagesGiovanni Bottiroli - Return To Literature. A Manifesto in Favour of Theory and Against Methodologically Reactionary Studies (Cultural Studies Etc.)RodrigoNo ratings yet

- When They Read What We WriteDocument30 pagesWhen They Read What We WriteRodrgo GraçaNo ratings yet

- 3247d8 - at The Intersection of Text and InterpretationDocument12 pages3247d8 - at The Intersection of Text and InterpretationMuhammad Danish ZulfiqarNo ratings yet

- +culler Whither Comparative LiteratureDocument14 pages+culler Whither Comparative Literaturekolektor2012No ratings yet

- Lyric, History, and Genre - Jonathan CullerDocument21 pagesLyric, History, and Genre - Jonathan CullerJulietceteraNo ratings yet

- Jlin 2004 14 2 297Document2 pagesJlin 2004 14 2 297untuk sembarang dunia mayaNo ratings yet

- HYMES An Ethnographic PerspectiveDocument16 pagesHYMES An Ethnographic PerspectivelouiseianeNo ratings yet

- Boris Groys (2012) Introduction To LONDON: VERSO. ISBN 9781844677566Document6 pagesBoris Groys (2012) Introduction To LONDON: VERSO. ISBN 9781844677566maranamaxNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical Analysis - Towards A Tropology of ReadingDocument8 pagesRhetorical Analysis - Towards A Tropology of ReadingLJDLC jOALNo ratings yet

- The Framework of IdeasDocument15 pagesThe Framework of IdeasBernardus BataraNo ratings yet

- Management Research and Literary Criticism: Cite This PaperDocument9 pagesManagement Research and Literary Criticism: Cite This PaperNeil SibalNo ratings yet

- Northrop FryeDocument13 pagesNorthrop FryeANKIT KUMAR DUBEYNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Society and John G. Cawelti's Adventure, Mystery, and Romance I OfferDocument17 pagesReview Article: Society and John G. Cawelti's Adventure, Mystery, and Romance I OfferLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Context-Sensitivity and Its Feedback The Two-Sidedness of Humanistic DiscourseDocument35 pagesContext-Sensitivity and Its Feedback The Two-Sidedness of Humanistic DiscourseMatheus MullerNo ratings yet

- Whither Comparative LiteratureDocument14 pagesWhither Comparative LiteratureLucas Accastello ChNo ratings yet

- Lectura. Swales Chapter. 3Document8 pagesLectura. Swales Chapter. 3Elena Denisa CioinacNo ratings yet

- Ecocriticism and Narrative Theory An IntroductionDocument12 pagesEcocriticism and Narrative Theory An IntroductionDianaLoresNo ratings yet

- TrouillotthesavageslotDocument15 pagesTrouillotthesavageslotCompanhia SambafroNo ratings yet

- (C. K. Ogden, I. A. Richards) The Meaning of MeaningDocument387 pages(C. K. Ogden, I. A. Richards) The Meaning of MeaningAdrian Nathan West100% (6)

- The Form of Reading-Empirical Studies of LiterarinessDocument15 pagesThe Form of Reading-Empirical Studies of LiterarinessAisha RahatNo ratings yet

- Narratología Postclásica Gerald PrinceDocument10 pagesNarratología Postclásica Gerald PrinceCChantakaNo ratings yet

- Traveling Concepts in The Humanities, A Rough Guide by Mieke BalDocument12 pagesTraveling Concepts in The Humanities, A Rough Guide by Mieke BalJana NaskovaNo ratings yet

- The Epistemology of Cognitive Literary Studies: Hart, F. Elizabeth (Faith Elizabeth), 1959Document22 pagesThe Epistemology of Cognitive Literary Studies: Hart, F. Elizabeth (Faith Elizabeth), 1959Michelle MorrisonNo ratings yet

- Fredric Jameson, ValencesDocument624 pagesFredric Jameson, ValencesIsidora Vasquez LeivaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press Harvard Divinity SchoolDocument13 pagesCambridge University Press Harvard Divinity Schoolcri28No ratings yet

- Anthropological PoeticsDocument32 pagesAnthropological PoeticsRogers Tabe OrockNo ratings yet

- The MIT Press American Academy of Arts & SciencesDocument30 pagesThe MIT Press American Academy of Arts & SciencesWilliam Joseph CarringtonNo ratings yet

- Ecocriticism and Narrative Theory An IntroductionDocument12 pagesEcocriticism and Narrative Theory An IntroductionIdriss BenkacemNo ratings yet

- Duke University Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Boundary 2Document31 pagesDuke University Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Boundary 2mmaialenNo ratings yet

- FERGUSON. Reading IntersectionalityDocument9 pagesFERGUSON. Reading IntersectionalityMarco Antonio GavérioNo ratings yet

- Gans 1990Document15 pagesGans 1990twerkterNo ratings yet

- University of Wisconsin PressDocument18 pagesUniversity of Wisconsin Pressmassoliti100% (1)

- The Current Conjuncture in TheoryDocument8 pagesThe Current Conjuncture in TheorygonzalezcanosaNo ratings yet

- University of Sialkot, PakistanDocument5 pagesUniversity of Sialkot, PakistanAnum MalikNo ratings yet

- Fear of TheoryDocument19 pagesFear of TheoryGurmeet SinghNo ratings yet

- Thomas Pavel - Fictional Worlds (1986, Harvard University Press)Document85 pagesThomas Pavel - Fictional Worlds (1986, Harvard University Press)Carmen CarrascoNo ratings yet

- Valences of The Dialectic2Document625 pagesValences of The Dialectic2Eric OwensNo ratings yet

- But Is It Sci-Fi - Theory of GenreDocument28 pagesBut Is It Sci-Fi - Theory of GenreIcha SarahNo ratings yet

- File 566 PDFDocument8 pagesFile 566 PDFmikorka kalmanNo ratings yet

- Inconceivable Effects: Ethics through Twentieth-Century German Literature, Thought, and FilmFrom EverandInconceivable Effects: Ethics through Twentieth-Century German Literature, Thought, and FilmNo ratings yet

- The Prison-House of Language: A Critical Account of Structuralism and Russian FormalismFrom EverandThe Prison-House of Language: A Critical Account of Structuralism and Russian FormalismRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- The Art of Veiled Speech: Self-Censorship from Aristophanes to HobbesFrom EverandThe Art of Veiled Speech: Self-Censorship from Aristophanes to HobbesNo ratings yet

- Reflecting on Reflexivity: The Human Condition as an Ontological SurpriseFrom EverandReflecting on Reflexivity: The Human Condition as an Ontological SurpriseNo ratings yet

- History and Tropology: The Rise and Fall of MetaphorFrom EverandHistory and Tropology: The Rise and Fall of MetaphorRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- W7 Sperber and Wilson Modularity Mind ReadingDocument21 pagesW7 Sperber and Wilson Modularity Mind ReadingLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- States Parties To The Rome Statute of The International Criminal Court - Wikipedia, The Free EncycloDocument23 pagesStates Parties To The Rome Statute of The International Criminal Court - Wikipedia, The Free EncycloLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- AMC Jun Solutions 2008Document5 pagesAMC Jun Solutions 2008Laura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- Anglo-Saxon Riddle - Anonymous, c.950 A.D.Anglo-Saxon RiddleDocument1 pageAnglo-Saxon Riddle - Anonymous, c.950 A.D.Anglo-Saxon RiddleLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- 3 2 Wisnewski1Document17 pages3 2 Wisnewski1Laura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- 3623 - 15 - Uos Outline Final VersionDocument12 pages3623 - 15 - Uos Outline Final VersionLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- Speech Poetry Chair Barry SpurrDocument13 pagesSpeech Poetry Chair Barry SpurrLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- HicksDocument6 pagesHicksLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- Cynthia Ozick InterviewDocument30 pagesCynthia Ozick InterviewLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- Onym - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFDocument6 pagesOnym - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- Brinton02 HTMLDocument9 pagesBrinton02 HTMLLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- Onym - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFDocument6 pagesOnym - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- 15canale PDFDocument22 pages15canale PDFLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

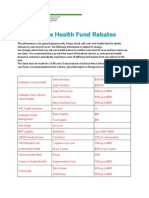

- TENs Private Health Fund RebatesDocument3 pagesTENs Private Health Fund RebatesLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- GoldDocument8 pagesGoldLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- Platinum ExtrasDocument8 pagesPlatinum ExtrasLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- Join Files Student Membership 09 RevisedDocument2 pagesJoin Files Student Membership 09 RevisedLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- Identifying Meters PracticeDocument6 pagesIdentifying Meters PracticeLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- General Product Guide-2Document17 pagesGeneral Product Guide-2Laura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- General Product Guide-2Document17 pagesGeneral Product Guide-2Laura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- GMHBA FactSheet G75 PDFDocument5 pagesGMHBA FactSheet G75 PDFLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- Beyond JokeDocument16 pagesBeyond JokeMaxwell DemonNo ratings yet

- Bupa GoldExtras NSW ACT 0415Document3 pagesBupa GoldExtras NSW ACT 0415Laura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- Summary Essential ExtrasDocument3 pagesSummary Essential ExtrasLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- Bupa GoldExtras NSW ACT 0415Document3 pagesBupa GoldExtras NSW ACT 0415Laura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- Bupa GoldExtras NSW ACT 0415Document3 pagesBupa GoldExtras NSW ACT 0415Laura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- HIFDomesticCoverPDS 2Document28 pagesHIFDomesticCoverPDS 2Laura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- PlatinumDocument8 pagesPlatinumLaura Leander WildeNo ratings yet

- Walmart Assignment1Document13 pagesWalmart Assignment1kingkammyNo ratings yet

- Consti II Case ListDocument44 pagesConsti II Case ListGeron Gabriell SisonNo ratings yet

- Disha Publication Previous Years Problems On Current Electricity For NEET. CB1198675309 PDFDocument24 pagesDisha Publication Previous Years Problems On Current Electricity For NEET. CB1198675309 PDFHarsh AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Lista Materijala WordDocument8 pagesLista Materijala WordAdis MacanovicNo ratings yet

- BreadTalk - Annual Report 2014Document86 pagesBreadTalk - Annual Report 2014Vicky NeoNo ratings yet

- Conspicuous Consumption-A Literature ReviewDocument15 pagesConspicuous Consumption-A Literature Reviewlieu_hyacinthNo ratings yet

- Caucasus University Caucasus Doctoral School SyllabusDocument8 pagesCaucasus University Caucasus Doctoral School SyllabusSimonNo ratings yet

- ContinentalDocument61 pagesContinentalSuganya RamachandranNo ratings yet

- The Passive Aggressive Disorder PDFDocument13 pagesThe Passive Aggressive Disorder PDFPhany Ezail UdudecNo ratings yet

- Scanned - National Learning CampDocument2 pagesScanned - National Learning CampJOHN JORICO JARABANo ratings yet

- Recurrent: or Reinfection Susceptible People: Adult With Low Im Munity (Especially HIV Patient) Pathologic ChangesDocument36 pagesRecurrent: or Reinfection Susceptible People: Adult With Low Im Munity (Especially HIV Patient) Pathologic ChangesOsama SaidatNo ratings yet

- High Court Judgment On Ex Party DecreeDocument2 pagesHigh Court Judgment On Ex Party Decreeprashant pathakNo ratings yet

- Past Simple Present Perfect ExercisesDocument3 pagesPast Simple Present Perfect ExercisesAmanda Trujillo100% (1)

- Lecture 7Document28 pagesLecture 7Nkugwa Mark WilliamNo ratings yet

- Virulence: Factors in Escherichia Coli Urinary Tract InfectionDocument49 pagesVirulence: Factors in Escherichia Coli Urinary Tract Infectionfajar nugrahaNo ratings yet

- Workshop BayesDocument534 pagesWorkshop Bayesapi-27836396No ratings yet

- BA BBA Law of Crimes II CRPC SEM IV - 11Document6 pagesBA BBA Law of Crimes II CRPC SEM IV - 11krish bhatia100% (1)

- Asterisk 10.0.0 Beta1 SummaryDocument113 pagesAsterisk 10.0.0 Beta1 SummaryFaynman EinsteinNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument50 pagesPDFWalaa RaslanNo ratings yet

- t10 2010 Jun QDocument10 pagest10 2010 Jun QAjay TakiarNo ratings yet

- Demo StatDocument5 pagesDemo StatCalventas Tualla Khaye JhayeNo ratings yet

- City Living: Centro de Lenguas ExtranjerasDocument2 pagesCity Living: Centro de Lenguas Extranjerascolombia RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Settling The Debate On Birth Order and PersonalityDocument2 pagesSettling The Debate On Birth Order and PersonalityAimanNo ratings yet

- Infinitives or Gerunds PDFDocument2 pagesInfinitives or Gerunds PDFRosa 06No ratings yet

- Oniom PDFDocument119 pagesOniom PDFIsaac Huidobro MeezsNo ratings yet

- Spoken KashmiriDocument120 pagesSpoken KashmiriGourav AroraNo ratings yet

- 145class 7 Integers CH 1Document2 pages145class 7 Integers CH 17A04Aditya MayankNo ratings yet