Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Research On Collaboration, Business Communication and Technology

Uploaded by

manique_abeyrat2469Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Research On Collaboration, Business Communication and Technology

Uploaded by

manique_abeyrat2469Copyright:

Available Formats

JOURNAL

10.1177/0021943604271958

Forman,

Markus

OF BUSINESS

/ COLLABORATION,

COMMUNICATION

COMMUNICATION, TECHNOLOGY

RESEARCH ON COLLABORATION,

BUSINESS COMMUNICATION,

AND TECHNOLOGY:

Reflections on an Interdisciplinary

Academic Collaboration

Janis Forman

University of California, Los Angeles

M. Lynne Markus

Bentley College

Interdisciplinary research is often recommended and occasionally studied, but little has been written

about the personal, practical, and methodological issues involved in doing it. In this article, the authors

describe one particular research collaboration between a business communication scholar and an information systems researcher. They present their observations about the political pitfalls and personal benefits of their interdisciplinary collaboration. As they attempt to generalize from their experience, the

authors conclude that politics in the broadest sense of the term is the most critical challenge to the

conduct of interdisciplinary research.

Keywords: collaboration; interdisciplinary; computer-supported writing; management communication; information systems

Following publication of the Forum in the January 2004 issue of the Journal of

Business Communication (JBC), the topic of collaborative writing again comes to

the pages of JBC. Although enough research has been done on the topic to warrant a

review (Forman, 2004; Thompson, 2001), important areas of collaborative writing

research remain relatively underexplored. One such area is interdisciplinary academic collaborations on the topic of collaborative writing.

Janis Forman (Ph.D., Rutgers University, 1980) is director of management communication and an

adjunct full professor of management in the UCLA Anderson School of Management at the University of

California, Los Angeles. M. Lynne Markus (Ph.D., Case Western Reserve University, 1979) is trustee

professor of management in the Management Department at Bentley College. The authors would like to

thank the following people for their assistance with this article: Marjorie Horton (The Center for

Machine Intelligence), Allen S. Lee (Virginia Commonwealth University School of Business), Wanda

Orlikowski (MIT Sloan School of Management), Priscilla Rogers (The University of Michigan School of

Business Adminstration), Barbara Shwom (Northwestern Universitys writing programs), and JoAnne

Yates (MIT Sloan School of Management). Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed

to Dr. Janis Forman, 110 Westwood Plaza, Suite 420, Box 951481, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1481; e-mail:

Janis.forman@anderson.ucla.edu.

Journal of Business Communication, Volume 42, Number 1, January 2005 78-102

DOI: 10.1177/0021943604271958

2005 by the Association for Business Communication

Forman, Markus / COLLABORATION, COMMUNICATION, TECHNOLOGY

79

In academia, interdisciplinary research is often recommended, both as a general

value and as an approach to understanding particular research questions, but little

has been written about the personal, practical, or methodological issues it entails

(Barton, 2001; Lowry, Curtis, & Lowry, 2004; OConnor, Rice, Peters, & Veryzer,

2003). Interdisciplinary collaborations bring an extra element of difficulty to an

already challenging task. As Larry Smeltzer (1994) notes in commenting on Kitty

Lockers (1994) thoughts about interdisciplinary research:

She states that business communication is interdisciplinary; however, I am not

sure that many of us are interdisciplinary. We simply bring our own disciplinary

training to the forum and tend to ignore valuable contributions made by those

using a different perspective. (Smeltzer, 1994, p. 158)

Similarly, in the field of organizational behavior, OConnor et al. (2003) point

out that researchers run the risk of interpreting . . . data through their own

thought worlds. . . . [T]hought worlds exist in academia . . . and work against

researchers achievement of a thorough understanding of complex phenomena

(p. 354).

Investigations of computer-supported collaborative writing qualify as a complex phenomenon to which the divergent academic disciplines of business communication and information systems can usefully be brought to bear. From 1985

through 1987, we undertook an interdisciplinary collaborative research project on

that topic, hoping to learn from the convergence of our respective fields. In 1993a

few years after the study was completedwe wrote up our observations on our collaboration. For various reasons, these observations were never published, but the

recent JBC Forum on collaborative writing recalls our project to mind. Reflecting

on those observations in 2004, we believe that they remain current todayand add

to the discussions on collaborative writing and interdisciplinary research.

DISCIPLINES AND INTERDISCIPLINARITY: BUSINESS

COMMUNICATION AND INFORMATION SYSTEMS

The core and boundaries of the academic fields of business communication and

information systems are hotly contested. (See, for example, Blyler, 1995, Forman,

1998, and Smeltzer, 1993, on business communication, and Benbasat & Zmud,

2003, and Briggs, Nunamaker, & Sprague, 1999/2000, on information systems.)

Each field issues periodic calls for diversity and openness to other points of view.

And each field has periodic crises of faith in which members wonder if the field will

ever achieve disciplinary status. (See Dulek, 1993, Graham & Thralls, 1998, Rentz,

1993, and Shaw, 1993, on business communication and Banville & Landry, 1989,

Baskerville & Myers, 2002, and Benbasat & Weber, 1996, on information systems.) It is not our intention in this article to engage these concerns, but it is important to understand that interdisciplinary conflicts can arise to some extent even in

80

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION

collaborations among the members of the same field. Indeed, across two fields the

clash of thought worlds can be much greater, even when they share the common

denominator of business.

By the discipline of business communication, we include those research questions, theoretical concerns, and methodological practices that are found in articles

published by the major journals, namely, Business Communication Quarterly, the

Journal of Business Communication, the Journal of Business and Technical Communication, Management Communication Quarterly, and Technical Communication Quarterly. By the early 1990s, some of the leading scholars in business communication strongly advocated opening research in the discipline to outside

influences. This rhetoric of interdisciplinarityexperts public statements about

the need to include other disciplines in the study of business communication, and

public acknowledgment of the goodness of inclusivenesstook center stage in

Larry Smeltzer and James Suchans introduction to the 1991 special issue of JBC

on theory in the discipline: Business communication research continues to represent a pastiche of theoretical perspectives borrowed from organizational behavior,

speech communication, rhetoric, composition, organizational communication,

marketing, international business, and a number of other areas (p. 181).

Other scholars followed suit, especially in the 1993 special issue of JBC on business communication as a discipline. (See, in particular, Gary Shaw, 1993, on business communication as a hybrid discipline based upon the fields of communication, management, and rhetoric.) Interest in the topic deepened in the late 1990s and

the first decade of the new century. For example, Margaret Baker Graham and

Charlotte Thralls (1998) discussed the interdisciplinary dimensions of the field as a

central concern in the formation of the discipline, as did Priscilla Rogers (2001) in

her Outstanding Researcher Award lecture given at the 2000 Association for Business Communication Conference and those who commented on her presentation in

a later issue of JBC. (See Bargiela-Chiappini & Nickerson, 2001; Ryan, 2001a,

2001b; Wardrope, 2001, for the commentary.)

Information systems (IS) started as an area of interest at the intersection of

computer science, management science, and organizational science (Culnan &

Swanson, 1986). Over the years, the field has also drawn in other perspectives,

notably psychology, economics, and strategy. Among the leading journals in the

field today are Management Information Systems Quarterly, Information Systems

Research, Journal of the Association for Information Systems, and Journal of Management Information Systems. As technology developed, emerging challenges

linked to the advances in technology often lead to calls for the importation of yet

more perspectives. For example, electronic commerce has led many IS researchers

to explore the marketing and supply chain literatures. Just as frequently, fears of

fragmentation stimulate calls for stronger boundaries and a more stable core

(Banville & Landry, 1989; Benbasat & Zmud, 2003).

Researchers who hope to bridge two fields as different as business communication and information systems face a double challenge. Not only must they reconcile

Forman, Markus / COLLABORATION, COMMUNICATION, TECHNOLOGY

81

the conflicting voices within one community of scholars, but they must also find a

way to understand the conflicts in another. How can a researcher who has already

studied the constituent disciplines of business communicationcomposition, rhetoric, organizational communication, among othersalso achieve competence in

the relevant constituent disciplines of information systemscomputer science,

operations research, management science, and organizational behavior, among

othersor vice versa? Is the need to bring in still other disciplines not simply too

much to ask of specialists in interdisciplinary fields who enter a new research

domain?

Clearly, interdisciplinary academic collaborations are one way to bring the perspectives of different disciplines to bear on complex, multifaceted research topics.

But despite considerable research on academic collaboration and communication

(see, for instance, Galegher, Kraut, & Egido, 1990; Latour & Woolgar, 1979;

OConnor et al., 2003), the rhetoric encouraging interdisciplinary research

(Barton, 2001) has far outstripped the study of such undertakings. Little has been

written about academic research that crosses disciplinary lines. What little there is

suggests that the challenges facing interdisciplinary research teams are great.

OConnor et al. (2003) note that academic environments have pressures that discourage and foil interdisciplinary collaborations. For example, junior faculty pursuing tenure are expected to publish a certain number of articles in the high-ranking

journals of their specific field. Interdisciplinary collaboration appears to many to be

a highly risky endeavor because the possibility of publication in the high-ranking

journals of ones home discipline may be more difficult for studies that cut across

disciplines than for those that are clearly linked to the home discipline. Should a

junior faculty member manage to achieve a sufficient number of publications in

high-ranking journals, he or she may face an additional hurdle in considering

collaborative interdisciplinary research:

There is no explicit discussion offered regarding the appropriate degrees to which

researchers acting as a team should influence one anothers thinking, when in the

process such interaction should take place . . . , or what the best mechanisms are at

different points in the process for engaging in such interaction. (OConnor et al.,

2003, pp. 353-354)

At the end of the road, the potential rewardswith an emphasis on potentialinclude a richer understanding of complex phenomena but at the cost of

time spent learning to work collaboratively across disciplinary boundaries.

One way to close the gap between the rhetoric and the practice of interdisciplinary academic collaborations is through stories. These stories, we argue, can give

substance to the rhetoric of interdisciplinary collaboration while suggesting problems in its theory and practice. (In his Outstanding Researcher Award lecture given

at the 2003 Association for Business Communication Conference, Jim Suchan,

2004, urged researchers and practitioners to begin telling their stories as an

approach to developing knowledge in the discipline.) In this article, we offer our

82

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION

own story of interdisciplinary collaboration for a multiyear research study of information technology and collaborative writing involving the collaboration of a

business communication specialist and a researcher in information systems.

One way to close the gap between the

rhetoric and the practice of interdisciplinary academic collaborations is

through stories. These stories, we

argue, can give substance to the rhetoric of interdisciplinary collaboration

while suggesting problems in its theory

and practice.

We begin with a narrative of our collaboration, written (except for minor editing) in 1993, a few years after our joint study, conducted between 1985 and 1987,

was concluded. This narrative describes the study, how we worked together, the

written products of the study, and our contemporaneous observations about the factors that spawned and shaped our collaboration and our assessment of its benefits.

Then we revisit this story from the perspective of 2004, considering the issues that

arise in interdisciplinary collaboration more generallyespecially the politics of

the academyand conclude with suggestions for additional research.

OUR INTERDISCIPLINARY COLLABORATION THEN . . .

Our collaboration involved a 2-year study of information technology use in collaborative writing. In the first year of the study (1985-1986), we closely observed

teams of master of business administration (MBA) students while they conducted

6-month consulting projects that culminated in strategic reports for real client organizations. As a result of our observations, we identified many problems in collaboration attributable to poor group dynamics, writing problems, and lack of appropriate information technologies. In the 2nd year of the study (1986-1987), we selected

a package of information technologies that addressed, we believed, many of the

technology needs identified during our initial investigation. We solicited four

teams of volunteers, had them trained in the use of information technology, and

observed how they collaborated in their consulting and writing tasks and how they

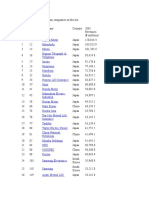

used technology while doing so. (See Figure 1 for details of the project rationale,

the groups studied, the information technology used, and the research procedures.)

Forman, Markus / COLLABORATION, COMMUNICATION, TECHNOLOGY

83

Project Rationale

This project focuses on the uses of computer-mediated group writing in the managerial problemsolving, decision-making, and communication tasks that take place in the Field Study process. Computer-mediated group writing includes electronic messaging, computer conferencing, and group writing

software. Since Field Study resembles the small group project activity that many managers perform,

Field Study research provides an ideal testbed for exploring ways the new information technology can

contribute to overall project success.

Dr. Forman will focus upon how computer-mediated technology influences the creation of two groupwritten documents for Field Study, namely the communications component and the final report.

Professor Markus will look at 1) the different material constraints and enablements of traditional versus computer-mediated group writing and 2) the influence of computer-mediated technology on the time

use and interaction patterns of Field Study teams.

The thesis of this study is that computer-mediated technology will enhance group problem-solving,

decision-making, and communication tasks, but will require new users of the technology to master a set

of new skills to use it effectively. (from a joint-authored memo requesting funding for the study, October

10, 1985)

The Groups and Their Task

As a requirement for their master of business administration (MBA) degree, 2nd-year students at

UCLA must complete a field study. The field study is a strategic consultation for a real client; it culminates in an oral and a written report (approximately 25 pages) to the management of the client company.

The report describes a strategic problem or opportunity facing the company, an analysis of it, and recommendations for client company management. In addition to this final report, several intermediate written

products are required of the field study teams. The field study is conducted over two quarters (6 months)

in teams of three to five students, during which time students take other courses, conduct job searches,

and may engage in part-time employment. Teams are supervised by two faculty advisors; a single grade,

common to all members of the team, is given for both quarters work.

The Information Technology

Each participant in our study was provided an information technology package with four key elements:

(a) the loan of an IBM personal computer (PC) Convertible with a portable dot-matrix draft printer and an

external modem, (b) a complimentary copy of Framework II, an integrated word processing, spreadsheet, database, graphics, and terminal emulation package, (c) access to an electronic communication

package called TEAMate with three key features: electronic messaging, electronic filing/bulletin board,

and electronic file transfer, and (d) extensive initial training and ongoing support. (TEAMate predated

Lotus NOTESa widely used software package with functions similar to those of TEAMate.) Access to

the telecommunications package was limited to the team members, their faculty advisors, and the study

research staff.

Research Procedures

Four field study teams (three teams of four students, one team of three students) and their faculty advisors volunteered to participate in the study during the fall and winter quarters of the 1986-1987 academic

year. In return for the loan of the equipment and training in its use, participants granted permission for

researchers to observe the teams at work; to record or collect oral, written, and computer communications; and to interview them individually 4 times over the course of the study. At the midpoint of the

project, we conducted taped group interviews evaluating each teams interpersonal process during

the creation of an early deliverable, a five-page proposal. Participants were not required to use the studysupplied technology except to demonstrate competence in its use. Our contract with participants did not

enable us to coerce them to use the technology, and we had limited reward power over them.

Figure 1. Our Collaborative Research Project

84

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION

Method of Working Together

Unlike some other interdisciplinary projects, for this one we did not work dialectically to create a set of agreed-upon, shared research questions that synthesized

our disciplinary perspectives. Instead, we pursued separate research agendas

within the context of our shared data collection and analysis. We collaborated fully

in many aspects of the project: the initial project proposal, data collection, project

administration, and final data analysis. Naturally, some division of labor occurred

for reasons both of efficiencyit made sense to split up the data-gathering tasks

and of expertiseit made more sense for Janis than Lynne to evaluate the teams

writing processes and written products and for Lynne rather than Janis to evaluate

the technology and design of the technology training.

To some extent, the data collection reflected a compromise rather than a synthesis of interests. Janis required assembly of all intermediate drafts whereas Lynne

insisted on computer monitoring of communication behavior. Nonetheless, we

jointly agreed about the best procedures for collecting, coding, and analyzing all

dataagreements that involved many hours of meeting and discussion. For

instance, we strove for, and achieved, consensus about a ranking of the teams in

terms of writing quality, interpersonal effectiveness, and use of technology.

Written Research Products

We departed from our pattern of collaboration only in the publication of our

research, whichexcept for this articlewas written separately for specialized

journals in our respective fields and reflects our concern for pursuing questions of

interest to our home disciplines and our perceptions that the key publication outlets

for each field lacked the necessary readiness to publish work in the others home

discipline. For example, merely defining the meaning of key terms in one field for

publication in another would not suffice. Such key terms themselvesfor instance,

collaborative writing in business communicationcarry a history of meanings

and research claims that could not be easily transferred to an information technology publication. Table 1 provides some details of our separate publications from

this joint research: article titles, journals where published, intended audiences,

research questions, and abstracts.

Personal Reasons for Launching the Project

Our predisposition toward interdisciplinarity was essential in creating and sustaining our collaboration. Janis initially had several practical and theoretical reasons for undertaking an interdisciplinary project on collaborative writing and computing. As her earlier interest in collaborative writing expanded to include a

concern for the relationship between technology and collaboration, she realized

that she lacked the expertise to conduct a study of collaboration involving technology. Very early in the project, she also learned that an intervention study requires

85

Article

abstract

Journal

where

published

Intended

audience

Research

questions

Article title

Table 1.

Information Technology & People (1992)

Asynchronous Tools in Small Face-to-Face Groups

Lynnes Publication

Information systems researchers with an interest in the use and effects of

information technology

When asynchronous technologies are newly introduced in management student groups that can meet face to face, will the groups adopt these technologies for communicating among team members?

For what purposes, in what manner, and how extensively will members of

face-to-face groups use asynchronous technologies if these systems are

introduced primarily to support communications within the groups rather

than with outsiders who are less accessible physically?

How do small groups with the ability to meet face-to-face adopt and use asynThis article identifies problems in the computer-supported group

chronous technologies, such as electronic mail, file transfer, and electronic

writing of MBA [master of business administration] students

bulletin boards? This paper identifies a set of expectations about technology

who are both novice strategic report writers and novice users of

adoption and usage based on prior theory and research on information techtechnology that supports group work. These problems consist of

nology and work groups. After describing a longitudinal study in which the

lack of attention to readers needs, attitudes, and expectations;

adoption and usage of asynchronous technologies were observed in small

poor conflict management; leadership problems; genre confuface-to-face groups, the paper compares actual observations with the theorysion; shaky definition of the strategic problems; poor commitment and attitudes toward use of new technology; poor computer

based expectations. Expectations about electronic messaging and bulletin

policies and practices; and conflicting hardware and software

boards were generally supported. However, some groups used electronic file

preferences. The article suggests several reasons for these probtransfer in a way that theory did not predict: synchronously, to support faceto-face interaction. The one group to use the technology asynchronously did

lems, draws implications for instruction of computer-supported

so, in part, because of poor social relations: The technology enabled group

group writing, and suggests topics for further research.

members to maintain social distance while performing group tasks. The

implications of these findings for theory and future research are discussed.

Communication professionals in academe, business, science, and

government

What kinds of problems do novice management student groups

encounter in group writing?

What kinds of problems do these groups encounter in using

computer tools to support group writing?

Novices Work on Group Reports: Problems in Group Writing

and in Computer-Supported Group Writing

Journal of Business and Technical Communication (1991b)

Janiss Publication

Our Respective Publications

86

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION

the participation of someone experienced in working with computer vendors and in

choosing intelligently among technology optionstraining that Lynne had and

Janis did not. As important, either by sensibility or habit, she was interested in questions that defy disciplinary boundaries rather than in disciplinary-based research.

(Her first publication was jointly authored with a political theorist, a critical introduction to a work by Rousseau that reflected his ideas as a dramatist and a social

thinker [Barber & Forman, 1978].) She strongly concurred with Kenneth Burkes

(1984) notion of trained incapacity, the idea of limits to our understanding of

problems that result from training in a specific discipline with its necessary restrictions, namely, its underlying propositions, theories, and methodologies. (Burke

claimed to have borrowed the idea from Thorsten Veblen, who used it to describe

the limitations of financially trained business people in their approach to decision

making.)

As the study progressed, other reasons emerged for doing work with an IS

expert. With Lynnes assistance, Janis could formulate questions about writing and

computing that she sensed to be important but as a business communication specialist could not articulate specifically. These questions concerned how the computing policies and practices of groups contribute to their use of technology for

report writing, how the social dynamics of groups influence their choice and use of

groupware, how the geographical proximity of group members may affect their

decisions about which technology to use and when to use it (Forman, 1991a, p. 68),

and, perhaps, most important, how technology ought to be regarded as a set of

options or tools that writing groups manage or mismanage rather than as a machine,

a convenient substitute for pen and paper or a typewriter. At the same time, as an

additional benefit of interdisciplinary research, Janis found that she was forced to

look critically at her own research assumptions when explaining some of the premises of business communication to Lynne (Forman, 1991a, p. 68). For instance,

through her exchanges with Lynne, Janis learned that she adheredperhaps too

uncriticallyto the notion that writing is central to management tasks, when, in

fact, writing may sometimes be peripheral, just one of several communication

options from which managers may choose.

For her part, Lynne had several reasons for wanting to do interdisciplinary

research. She had had good experience working with a business communication

specialist before and so was favorably inclined to work with Janis. From a broader

perspective, she was intellectually predisposed to choose an interdiscipinary rather

than a single-discipline approach to research; her academic career is characterized

by interdisciplinary work. She came to the field of IS as a cross-disciplinary excursion from her doctoral training in organizational behavior. In her studies of the

behavioral aspects of information technology use, she had on various occasions

read deeply in the literatures of other disciplines such as anthropology, economics,

organizational communication, and sociology. She had been working on studies of

electronic mail use in organizations and was interested in getting more deeply into

the emerging study of computer-supported cooperative work (CSCW) or group-

Forman, Markus / COLLABORATION, COMMUNICATION, TECHNOLOGY

87

ware. The study with Janis offered the opportunity to work with a subject matter

expert in group writing, and Lynne thought that the very subject matter of the study

of groupware seemed to demand a collaborative effort. Finally, from a pragmatic

point of view, she knew that if she did not collaborate, she would have had to choose

a more bounded project, such as an analysis of the uses of electronic mail in an

organization, rather than the more challenging implementation study that she conducted with Janis.

In forming a research partnership, we agreed that we represented different disciplines in several ways. We had different academic training, had read different literatures, and used different research methodologies in our earlier separate studies. We

also had different professional affiliations and, as a result, we attended different

conferences and socialized with professionals in different discourse communities.

Within the Graduate School of Management (GSM) at University of California,

Los Angeles (UCLA), we were located in different units that had different objectives, and we taught subjects that occupied different places in the curriculum.

(Today, GSM is known as UCLA Anderson School of Management.)

We also recognized a number of similar disciplinary and professional concerns

without which we would not have shared enough common ground to undertake a

joint research venture. Both of us believe that knowledge is not objective, nor completely generalizable across individual cases. (On the continuum of research

approaches that Blyler, 1995, presents as a single one of functionalist versus interpretive, both of us fall somewhere in the middle.) As researchers and instructors in a

school of business, we were both interested in our students becoming leaders in the

business world and in their development of useful skills as well as interpretive

frameworks based in specific disciplines.

Institutional Support for Our Collaboration

Despite our predisposition toward interdisciplinary collaboration, this collaboration might not have occurred without institutional support in the form of research

funding and without the institutional placement of our respective disciplines. In the

mid-1980s, GSM had received a grant from IBM to conduct applied research on IS

and the education of managers. The grant provided the opportunity for the collaboration and for the design of the specific project in question, involving a technology

implementation and intervention. Because Lynne could calculate the amount of

work necessary to design and execute an effective intervention, she would never

even have dreamed of proposing one as a faculty member in a management school

in the absence of UCLAs receiving the IBM grant, which made funds available for

computer equipment. (She might also have conducted this kind of project if she had

been working for a computer or software product development firm, where equipment resources would presumably be available, but, of course, that is a different

story.)

88

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION

For her part, Janiss role as director of management communication at GSM

gave her a unique position with respect to the field study programthe setting

within which this study was conducted. Because of her involvement with field

study as the key communications instructor for all field study teams, senior administration at the school wanted Janis to consider ways in which to integrate computing into the instruction of group writing. Thus, except for the institutional accident

of Janiss services to the field study program, the collaboration would never have

occurred.

The institutional arrangements that

made our interdisciplinary collaboration

possible also placed constraints on its

outcomes, and in particular shaped our

decision to publish the major results of

our research as single-authored publications for journals in our respective

fields.

Other institutional arrangements also supported work such as ours. Both IS and

the teaching of business writing were housed in UCLAs management school,

GSM. In all likelihood, our study of the four student teams would not have occurred

had business writing been located in a traditional English department, that is, in a

literature-centered English department with little disciplinary diversity. In such

departments, interdisciplinary problem-centered research such as ours is rarely

funded. Furthermore, as a member of an English department, Janis would not

have had occasion to meet colleagues in IS, who typically belong to management

departments, for conversations about concerns shared across the disciplines. In

this instance, the shared concern was technology and group work. Moreover, if Janis had belonged to a traditional English department, her thinking about

computers and group writing would more likely have been influenced by humanities scholarshipthe disciplinary authority of literary theory and especially of

postmodernismthan by research on small group dynamics and IS. In the mid1980s, none of the IS literature appeared in business communication journals. Similarly, had Lynne been teaching in a school of computer science, library science, or

department of industrial engineering, there would have been considerably less

opportunity for her to interact with someone of Janiss background. We surmise,

then, that departmental goals and configurations, including the literal proximity to

one another of researchers from different disciplines, can be powerful agents in the

shaping of interdisciplinary research.

Forman, Markus / COLLABORATION, COMMUNICATION, TECHNOLOGY

89

Institutional Disincentives for Our Collaboration

The institutional arrangements that made our interdisciplinary collaboration

possible also placed constraints on its outcomes, and in particular shaped our decision to publish the major results of our research as single-authored publications for

journals in our respective fields. At GSM, more reward is given for a singleauthored publication than for a collaborative work. This bias, made clear in faculty

meetings and during Lynnes brief stint on the schools personnel committee, motivated us to publish as sole authors. In addition, although the school had recently

endorsed the importance of applied interdisciplinary research, building formal

mathematical theory was more valued than was empirical research focused on finding answers to practical business problems, which by their nature usually cross disciplines. The higher value placed on mathematical theory was demonstrated by the

relative speed with which such researchers achieved tenure and accelerated promotions. Furthermore, greater value was attributed to pure research in one of the

better established disciplines such as economics, finance, or marketing than to what

the institution considered to be marginal disciplines such as both business communication and IS. (See Graham & Thralls, 1998, Dulek, 1993, and Rentz, 1993, on

the struggles of business communication to gain disciplinary status and Banville &

Landry, 1989, and Benbasat & Zmud, 2003, on this issue as it pertains to IS.) In

fact, the discursive power of the disciplines of authorityeconomics, finance,

marketingdiminished the perceived value of knowledge resulting from collaborative work between business communication and IS experts. In Foucaults (1972)

words, not just anyone, finally, may speak of just anything (p. 216). The empowered disciplines have the most say as well as the authority to exclude others from

speaking.

Had either of us been more politically motivated, we would have delayed our

joint research until we had gained the requisite promotion or tenure. Interdisciplinary research seems to be toleratedeven rewardedwhen conducted by faculty

who have institutionally recognized reputations that have been built in a single discipline. Or, if organizational enfranchisement had been our central concern, we

would have aligned our research interests to those of an empowered discipline in

order to seek status by association with that discipline. Of course, such a decision

would have been at considerable expense to the concerns of our home disciplines

because, in all likelihood, these concerns would have been subordinated to those of

the empowered discipline. (See Warren Bennis, 1956, on how status conflict affects

interdisciplinary research teams.)

Barriers to Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Created by Our Respective Disciplines

The barriers to interdisciplinary collaboration extended beyond the confines of

our employing institution into our academic disciplines as well. This claim may be

substantiated by considering how our colleagues in IS and in business communica-

90

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION

tion, respectively, would evaluate our joint research. To simulate this situation we

gave an IS expert (an experienced journal editor) Janiss published article to

review as though she were submitting it for publication in a mainstream IS journal, and we asked a business communication expert to do the same with Lynnes

article. The results of these reviews, written in 1993 and summarized in Figure 2,

speak for themselves.

In both cases, our single-authored articles were unacceptable to members of

each others field, because these papers were insensitive to a host of audience

issues, including lack of focus on topics central to the journals readership and failure to explain literature cited from the others discipline or to cite literature appropriate to the disciplinary domain of the journal. In Janiss case, the reviewer noted

that she

has done little to establish any ties between her research and the current body of IS

research. Relevant to the failure of the four teams to use technology successfully,

for example, are the literatures of IS implementation, IS development, and CSCW.

According to the reviewer of Lynnes article, it seems to assume that the adoption of technology is an end in itself. Our field [business communication] is

more concerned with ways in which people adopt and adapt technology to meet

or expand their communication objectives. Viewed from a rhetorical perspective, these fundamental differences confirm Perelman and Olbrechts-Tytecas

(1969) assertion that there are agreements that are peculiar to the members of a

particular discipline and there is a discourse characteristic of each discipline

that summarize[s] an aggregate of acquired knowledge, rules, and conventions (p. 99). In sum, each article faced rejection in the others discipline on the

basis of differences about what issues are worthy of investigation and what

constitutes appropriate evidence and its presentation.

Despite the difficulties we experienced

in our collaborative research, and

despite the constraints imposed on our

work by our institutional setting, we

both found many benefits from our collaboration, both for this study and for

subsequent projects each of us has

undertaken.

Forman, Markus / COLLABORATION, COMMUNICATION, TECHNOLOGY

91

Rejection of Janiss Article

Journal where publication sought: Management Information Systems Quarterly (MISQ)

Reviewer who rejected the article: Allen S. Lee, (in 1993) Information Systems Department, College

of Business Administration, the University of Cincinnati, and member of the editorial board of MISQ; (in

2004) professor of information systems and associate dean for research, School of Business, Virginia

Commonwealth University, and former editor-in-chief of MISQ

Reviewers reasons for rejection of the articlePertinent excerpts from the review: The manuscript

currently addresses business communication specialists, of which there are few among the MISQ readership. MISQ readers have expectations that, I believe, the manuscript would not satisfy. These expectations pertain to (1) methodology/research-designand (2) relationship or relevance to the IS literature.

With regard to methodology and research design, it seems to me that the manuscript is doing a case

study. However, the manuscript makes no use of Robert K. Yins classic book, Case Study Research:

Design and Methods, 1989, or to Allen S. Lees article, A Scientific Methodology for MIS Case Studies, in the March 1989 issue of MISQ. Because case research is a form of research that MISQ readers

today would recognize and readily consider acceptable, I therefore strongly urge the author to reframe

his or her research design as one of a case study. Of course, there are also other genres of qualitative

research that MISQ readers would recognize and accept, and which, therefore, the author might also consider in addition to that of case studies. One such genre is grounded theory, which appears in the September 1993 issue of MISQ.

With regard to the manuscripts relationship or relevance to the IS literature, the author has done little

to establish any ties between her research and the current body of IS research. Relevant to the failure of

the four teams to use technology successfully, for example, are the literatures on IS implementation, IS

development, and CSCW [computer-supported cooperative work]. As I was reading the manuscript, I

was wondering what lessons these three literatures might have for the authors case study, as well as what

lessons the authors case study might have for these three literatures. To address the current body of IS

[information systems] research would increase the manuscripts interest in the eyes of the MISQ

readership.

Because I am not at all familiar with how technology can be used to support group writing, I found

much of the manuscript to be difficult to understand, simply because I had no idea as to how information

technology could conceivably support group writing. If, instead, early in the manuscript, there had been a

thick case description (whether actual or hypothetical) about who uses what tools to support this or that

particular task, then I could have understood the manuscript better in my first reading of it. Of course, I

was eventually able to infer who used (or could have used) what tools to support this or that particular

task; however, why not just tell the reader up front?

Rejection of Lynnes Article

Journal where publication sought: Journal of Business Communication

Reviewer who rejected the article: Barbara Shwom, Northwestern Universitys writing programs

and reviewer for business communication journals (in 2002) president of the Association for Business

Communication

Reviewers reasons for rejection of the articlePertinent excerpts from the review: This article is not

appropriate for this journal for one key reason: the article focuses primarily on technology; issues of

communication, though present in the article, are submerged.

Figure 2. Rejection of Janiss and Lynnes Articles for Publication in a Journal of the Others Discipline

(continued)

92

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION

Although the article does an excellent job of contextualizing its issues within a body of current

research, most of that research is from outside the fields our journal covers: business, technical, organization, or management communication. Very few of the references are from communication journals or

books; they are weighted heavily toward information systems and information technology. This poses

two problems for the article. Readers of our journal are unlikely to be familiar with any of the theories

presented or the researchers or research studies used as evidence. In addition, readers will have to work

hard to see the relevance of the research to communication issues.

The article assumes a knowledge of certain concepts in the communication technology research that

is not appropriate for the business communication audience. For example, the article assumes that everyone will be familiar with the concept of discretionary database, a term from outside the communication

fields.

Currently the article seems to assume that the adoption of technology is an end in itself. Our field is

more concerned with the ways in which people adopt and adapt technology to meet or expand their

communication objectives. The article should highlight the communication issues in technology and perhaps, in its conclusion, address the benefits of introducing asynchronous technologies into the workplace.

Figure 2 (continued)

Benefits of Our Collaboration

Despite the difficulties we experienced in our collaborative research, and

despite the constraints imposed on our work by our institutional setting, we both

found many benefits from our collaboration, both for this study and for subsequent

projects each of us has undertaken. For Janis, her work with Lynne has allowed her

to see the role of technology as a possible agent in group writing, influencing both

writing processes and products. What technology is chosen? How is it managed?

These are central questions in any study of collaborative writing that involves technology, and they have informed her research, teaching, and consulting. Prior to her

interdisciplinary work with Lynne, Janis unwittingly adopted an add technology

and mix approach to her understanding of technology and writing. (Lynne would

call this approach treating technology like a black box.) That is, she viewed technology as not much more than a machine that writers could use to facilitate writing.

For Lynne, her work with Janis has increased her rhetorical awareness and her recognition of how important the notion of discourse community is to the development of arguments. This new knowledge has assisted her in teaching graduate students and in her work as an associate editor and a reviewer for several journals in

various fields (communication, computer science, IS, organizational studies). It

has also influenced her work on a manuscript on the topic of writing as the methodology of qualitative research. For both of us, viewing the others radically different

interpretation of the same data puts into relief our respective theoretical and methodological views of how knowledge is made and what constitutes knowledge in our

respective disciplines. (In one instance, Janis used the idea of discourse community to interpret a teams unorthodox use of groupware, whereas Lynne used the

teams use of groupware to substantiate her argument about social distance and

technology.)

Perhaps most important for both of us, our knowledge of each others discipline

is based on experiencing an insiders perspective from another discipline and

Forman, Markus / COLLABORATION, COMMUNICATION, TECHNOLOGY

93

constitutes a tacit knowledge of the other discipline that cannot be easily acquired

by other means, such as by intensive reading of the literature in the others field.

Both this kind of tacit knowledge and work with colleagues from other disciplines

may be able to mitigate the hazards of wholesale, naive borrowing from other

disciplines and the tendency to overgeneralize theories from other disciplines

beyond their original intended application (see Rose, 1988, and Forman, 1998, on

this problem). At best, in the words of a collaborator from another business communication/IS team, the specialist from the other discipline can become an invisible author (M. S. Horton, personal communication, March 31, 1992), an internalized voice that opens up new methods of inquiry, new problem-solving approaches,

in work that follows an interdisciplinary effort.

How Typical Was Our Collaboration?

Reflecting in 1993 on our interdisciplinary collaboration naturally raised the

question of how it compared to other collaborations we had participated in as well

as to those of other business communication/IS teams. Was our interdisciplinary

work limited or extensive? From one perspective, our collaboration was extensive

in that we shared many aspects of the study, including lengthy analysis of the data.

But from another perspective, unlike other collaborations we had engaged in

(Forman & Katsky, 1986; Markus & Connolly, 1990), our collaboration was limited in that each of us developed a separate set of research questions and retained

our own intellectual property in the form of separate publications. Moreover, in the

generation of these single-authored publications, each of us subordinated the

others work both in the argument and in the writing process. In addition, our reading of each others manuscripts was limited to a review for readability and for

accuracy of details drawn from our pooled data.

One explanation for our decision to publish separately lies in the immaturity of

combined research efforts in business communication and IS at the time of our

study. There were, in fact, no other studies published in the late 1980s that represented this kind of collaboration and, hence, there were no theoretical bases or practices that we could build upon. This contrasts to the state of research by the mid1990s; collaborations between researchers in the two disciplines who publish

together, in particular the work of Priscilla S. Rogers and Marjorie S. Horton and

that of JoAnne Yates and Wanda J. Orlikowski, as well as studies on technology and

writing that link written communication to other disciplines (Ferrara, Brunner, &

Whittemore, 1991), offered precedent for further interdisciplinary work.

Negotiation Between Collaborators

Of course, collaborative research even within a single discipline is characterized

by negotiation, as collaborators Lisa Ede and Andrea Lunsford (1983, 1990)

reported in the mid-1980s and early 1990s in their discussions of the differences in

each others composing processes and in their routines for conducting research.

94

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION

But negotiations between collaborators from different disciplines can compound

these challenges by introducing potential incompatibilities in the methods and

underlying assumptions of each of the disciplines involved (although members of

the same discipline may disagree vehemently if their theoretical or methodological

views differ). In our case, we debated about data interpretation, especially in our

coding of teams according to variables such as group dynamics and experience

with technology, and in our creation of case histories for each team.

In the early 1990s, intellectual debate based on the differing disciplinary

home of collaborators was also amply attested to by two other pairs of business

communication/IS researchers, Priscilla S. Rogers and Marjorie S. Horton of the

University of Michigan and JoAnne Yates and Wanda J. Orlikowski of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Horton and Rogers engaged in frequent debate

about what constitutes data, one arguing for quantitative methods and the other for

qualitative (M. S. Horton & P. S. Rogers, personal communication, March 31,

1992). Yates summed up her negotiations with Orlikowski as a protracted process in which each of them was aware of her own core beliefs and of those areas

in which they were willing to be persuaded (J. Yates, personal communication,

April 7, 1992).

Yet, despite the costs in time and effort, negotiation represents a key strength of

interdisciplinary collaboration. The Orlikowski-Yates team concurred that debate

and dialectic fostered the kind of invention that neither collaborator alone could

have achieved. In our collaboration, we bypassed the difficulties of such negotiation by agreeing early to study questions of interest in our respective disciplines.

This limitation may have been partially attenuated by our extensive debate about

data interpretation.

. . . AND NOW: SOME GENERALIZATIONS ON

INTERDISCIPLINARY COLLABORATION IN 2004

Revisiting our project in 2004, we find that the politics of such effortspolitics

in the broadest sense of the termstrikes us as the most critical challenge to the

conduct of such research. Interdisciplinary collaborators must conduct their work

within the context of the opportunities and constraints offered by institutions and

disciplines.

Institutional Enabling of and Constraints

Upon Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Interdisciplinary collaboration is embedded in and often deeply influenced by

the institutional settings in which it occurs. As discussed earlier, our placement

within a management department, even the location of our offices within close

proximity to each other, encouraged discussion between us, and eventually, a formal research project. Orlikowski and Yates view this issue similarly, although in

Forman, Markus / COLLABORATION, COMMUNICATION, TECHNOLOGY

95

their case they were and are members of a single departmentan incentive for joint

researchbut are located in different buildingsa constraint, but one they are able

to overcome (W. J. Orlikowski & J. Yates, personal communication, July 16, 2004).

Placement in an interdisciplinary program, think tank, or research center including business communication experts and experts from other disciplines would

make collaboration even easier, we believe, because the raison detre of such organizational units is facilitation of interdisciplinary work, and the reward structure in

such units favors interdisciplinary efforts. This incentive for interdisciplinary

research has been the case for the Orlikowski-Yates team over the past decade: the

Center for Coordination Science, which had funded each of us individually before

we began working together, enthusiastically supported our joint work (W. J.

Orlikowski & J. Yates, personal communication, July 16, 2004). Moreover, this

team is now 4 years into a 5-year National Science Foundation grant focused

explicitly on interdisciplinary work.

But institutions can constrain interdisciplinary collaboration as well. For example, Rogers notes that since the early 1990s at her home institution,

our two deans . . . seem to be moving faculty together again by disciplinary group

as offices become open. Meanwhile, interdisciplinary research and pedagogy is

less a topic of discussion, and faculty teams for projects have been reduced to one

primary and one secondary faculty member in the discipline directly related to the

nature of the project. (P. S. Rogers, personal communication, July 1, 2004)

(A similar movement to assign faculty office locations by disciplinary group has

also characterized GSM since moving into new facilities in the mid-1990s.)

In sum, challenges persist even in management schools that are home to several related fields (Boudreau, Hopp, McClain, & Thomas, 2003; Henderson,

Ganesh, & Chandy, 1990) and, in some instances, appear to have increased.

One of the least conducive settings for interdisciplinary work such as we have

described is the traditional English department. There, business communication

specialists who seek to work with experts in other fields need to make extra efforts

to arrange such work and to defend it, because social science research and collaboration tend to be devalued.

Opportunities and Constraints of

the Disciplines Upon Collaboration

Negotiation between collaborators from different disciplines cannot be separated from the receptivity of each discipline to borrowing from other fields. This

proved both advantageous and disadvantageous in our collaboration in the 1980s.

Although there had been no collaboration between business communication and IS

specialists prior to our research project, both disciplines espoused the value of contributions from other disciplines to further knowledgeand still do (see, e.g.,

Smeltzer & Suchan, 1991, on business communication and Benbasat & Zmud,

96

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION

2003, Fitzgerald, 2003, Paul, 2002, and Perry, 2003, on IS). In fact, by the early

1990s, cross citations had begun to appear in the major publications of each discipline. At present, IS seems a strong potential partner for business communication

researchers as the importance of electronic messaging and groupware to writing

processes and products is recognized (Lowry et al., 2004; E. M. Rogers &

Allbritton, 1995). Moreover, interdisciplinary partnerships may be able to bypass

the gatekeeping of single disciplines by publishing their work in the journals of

fields that are explicitly interdisciplinary, as is the case for the Orlikowski-Yates

team:

We chose to publish most of our work not in disciplinary journals, but in the interdisciplinary field of Organization Studies, in such outlets as ASQ, AMR, and

Organization Science. For both of us, these journals were perceived by Sloans

interdisciplinary Personnel Committee as more prestigious than the disciplinary

journals of IS and particularly of management communication. (W. J. Orlikowski

& J. Yates, personal communication, July 16, 2004)

On the other hand, interdisciplinary work may be discouraged by the lack of

publication outlets in business communication, in IS, or in some combination of

the two that create forums in which each discipline is on an equal footing. Commenting more generally about publication outlets for interdisciplinary work,

Rogers notes her recent experience in which her interdisciplinary work was

rejected by

three relevant journals before we finally got it accepted. Our first submission, to a

sister journal, was rejected outright, our second try with a different sister journal was rejected based on reviewer input, and, finally, our third submission, to a

journal directly in our field [management communication] was embraced. (P. S.

Rogers, personal communication, July 1, 2004)

Summarizing her experience, in the same communication, she concludes,

I seem to be experiencing more barriers to interdisciplinary thinking than

previously.

Where joint authorship occurs, the disciplinary focus of the publication outlet

results in an imbalance of authority over the text; the collaborator from the same

disciplinary focus as the publication outlet has a disproportionate say in the argument, organization, and voice of the text. For instance, in the case of this article,

Janis took the lead because this article has been submitted to a leading journal for

experts in business communication and because she is more familiar with discourse

conventions for communication articles and with the discussions about collaboration among these experts than is Lynne. Joint authorship representing equally

shared authority on the part of each collaborator can be very difficult, if not

impossible.

The maturity of each discipline relative to the research questions addressed by

the collaborators also influences interdisciplinary collaboration. As the abstract

Forman, Markus / COLLABORATION, COMMUNICATION, TECHNOLOGY

97

from Janiss article indicates (see Table 1), she drew upon the literatures of several

disciplines: from composition and rhetoric (references to audience analysis); from

social psychology and the management of small groups (references to leadership

and group conflict); from IS (references to computer policies and practices and to

conflicting hardware and software needs); and from composition (references to

pedagogy). On the other hand, Lynnes article (see Table 1) contains a central argument that is placed in an ongoing set of propositions about technology and group

work within IS. As she writes, the paper compares actual observations with the

theory-based expectationstheories that are widely accepted within IS. On the

basis of these abstracts, sociologist Murray Davis would say that IS is a more

mature discipline than is business communication, at least in terms of Lynnes argument as opposed to Janiss (at the time when the research was conducted): Lynnes

propositions confirm, extend, or work against accepted theories within IS, some of

which synthesized work in other disciplines. Her baseline is the taken-for-granted

assumption of the intellectual specialty itself (Davis, 1971, p. 330). By contrast,

Janiss work reflects thinking in a less mature discipline as far as computing and

group work are concerned. There are no established propositions in business

communication that her article addresses.

The relative maturity of the two disciplines partially explains why we decided to

work with some independence within the context of our collaborative project and

may suggest what motivates other collaborators to choose a similar pattern for

working together. As management theorist Warren Bennis (1956) has noted, interdisciplinary research may be discouraged by

the difficulty of sharing and combining concepts between disciplines at varying

stages of development. Interdisciplinary research infers a contemporaneity between

cultural products. . . . It may be that an attempt to cross disciplines at a conceptual

level may be destined for failure because of their lack of contemporaneity.

(p. 227).

NEW DIRECTIONS

This article has been our attempt to describe one extended interdisciplinary project and to comment on it from the perspective of 1993, the completion of our

research publications, and from the perspective of 2004more than a decade later.

In his Outstanding Researcher Award lecture given at the 2003 Association for

Business Communication Conference, Jim Suchan appealed to researchers to

begin telling their stories, arguing that stories are a legitimate and undervalued

method for advancing knowledge in the field as well as an approach that unearths

data and insights that would be otherwise overlooked. At a minimum, we hope that

our example will prompt those who conduct interdisciplinary collaborations to

begin telling their stories, especially as these stories anchor, in specific cases,

notions of what constitutes knowledge and knowledge making in business commu-

98

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION

nication and offer opportunities to test and define what is meant by interdisciplinary research in the discipline.

In his Outstanding Researcher Award

lecture given at the 2003 Association

for Business Communication Conference, Jim Suchan appealed to researchers to begin telling their stories, arguing

that stories are a legitimate and undervalued method for advancing knowledge in the field, as well as an approach

that unearths data and insights that

would be otherwise overlooked.

Increasingly, business communication specialists have claimed that knowledge

and knowledge making involve an openness to other disciplines, a turn toward

interdisciplinary work. But as even this one example shows, the idea of interdisciplinary approaches to business communication and the conduct of such work are

complex and problematic along several dimensions:

the nature of interdisciplinary work;

interdisciplinary teams;

the fortunes of the discipline;

the role of publication outlets and institutional politics.

The nature of interdisciplinary work: What is meant by interdisciplinary

work? Does it mean drawing on multiple research literatures, using a common

database for different audiences, and sharing interpretations of data? Or is it a

more global, synthetic kind of knowledge building represented by the research

of Horton and Rogers and of Orlikowski and Yates?

Interdisciplinary teams: Will a pattern emerge of business communication

experts displaying disciplinary loyalty in some of their research and moving

into interdisciplinary groups for other work, as in the case of the OrlikowskiYates partnership? If such a pattern emerges, what will it reveal about the kinds

of questions being investigated?

The fortunes of the discipline: If business communication continues to

demonstrate permeability, will it be open to all other disciplines or only to some,

Forman, Markus / COLLABORATION, COMMUNICATION, TECHNOLOGY

99

and for what reasons? Will there come a point at which openness causes the

breakdown of the field and the constitution of new ones born of collaborative

interdisciplinary effort and the recognition of a fundamental commonality

between once distinct disciplines? In other words, will business communication

experts build bridges to other disciplines or radically restructure the discipline?

(See Klein, 1990, pp. 27-28.)

The role of publication outlets and institutional politics: Because funding

agencies, educational institutions, and publication outlets can confer status and

authority, what role will they play in the fortunes of business communication?

The most long-standing and prolific of the teamsOrlikowski-Yateshas published most of their work in interdisciplinary journals. These journals are highly

respected by their home institution and also forced/enabled us to merge our

perspective and develop a more thoroughly combined one (W. J. Orlikowski &

J. Yates, personal communication, July 16, 2004).

Stories of interdisciplinary teams will help to address these issues. Analysis of

such stories, especially of the kinds of sharing that occur among researchers from

different disciplines, may help specify what is meant by saying that business communication is open to interdisciplinary approaches.

Beyond the telling of stories about interdisciplinary work as a way to address the

questions identified above, we offer two other recommendations: ethnographic

research on the work of interdisciplinary teams and cocitation studies of articles

published in business communication journals. As for the former, investigators

observations and interviews of interdisciplinary business communication and IS

teams (or of business communication researchers and researchers from any other

discipline) promise to yield insights about the nature of such research and the theoretical borrowings and transformations that characterize the growth of business

communication as a result of such collaboration. Research by sociologists of the

natural sciences may offer models for such study of collaborative interdisciplinary

research, in particular Latour and Woolgars (1979) participant-observer study of

team research in a scientific lab. As for the latter, researchers and theorists within IS

may provide business communication specialists with good examples (e.g., Culnan

& Swanson, 1986). Tracking those instances when a researcher cites any work of

any given author along with the work of any other author in a new document

(Culnan, 1987, p. 343) assists in determining the disciplines outside IS that are

influencing its growth. The same kind of tracking has begun for business communication (Reinsch & Lewis, 1993). Such analysis results in information about the various disciplines that have influenced business communication at different times and

in the work of different researchers and scholars, and might form the basis for historical analysis of business communications relationship to other disciplines.

Taken as a whole, personal stories, outside investigators ethnographic studies, and

cocitation analysis may illuminate how knowledge in business communication is

socially constructed, especially as this construction is influenced by outside experts.

100

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION

Our emphasis on the institutional context for interdisciplinary collaboration

underscores how such collaboration is a highly bounded activity that goes beyond

the dynamics between or among collaborators. The ability of business communication specialists to work with outside experts may depend upon institutional

arrangements. Institutions are not neutral; they can be gatekeepers or facilitators of

research. For this reason, business communication specialists located in traditional

English departments will have to make extra efforts to undertake interdisciplinary

work. Informal meeting places such as study groups and colloquia that bring

together experts from different disciplines may be one way to initiate such efforts.

For example, at GSM a colloquium series on the topic of groups in the workplace

attracted faculty from business communication, management, IS, public health,

psychology, and sociology. Those business communication specialists located in

professional schools or in interdisciplinary units rather than in traditional English

departments should find it easier to establish both formal and informal research

activities, and may be expected to lead attempts to apply other disciplines to

business communication.

The ability of business communication

specialists to work with outside experts

may depend upon institutional arrangements. Institutions are not neutral; they

can be gatekeepers or facilitators of

research.

If it is important to broaden the theoretical and methodological base for future

research in business communication, one avenue for such expansion is collaborative research with experts from other disciplines. Precedent is set for this kind of

work, but there is much more to be done. The conduct of such work should proceed

in tandem with the critical analysis that can clarify our understanding of business

communication as a discipline continually revitalized and redefined by the theories

and practices of other disciplines.

REFERENCES

Banville, C., & Landry, M. (1989). Can the field of MIS be disciplined? Communications of the ACM,

32(1), 48-60.

Barber, B., & Forman, J. (1978). Preface to Narcisse: Introduction. Political Theory, 4, 537-542.

Bargiela-Chiappini, F., & Nickerson, C. (2001). Partnership research: A response to Priscilla Rogers.

Journal of Business Communication, 38, 248-251.

Forman, Markus / COLLABORATION, COMMUNICATION, TECHNOLOGY

101

Barton, E. (2001). Design in observational research on the discourse of medicine: Toward disciplined

interdisciplinarity. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 15(3), 309-332.

Baskerville, R. L., & Myers, M. D. (2002). Information systems as a reference discipline. MIS Quarterly,

26(1), 1-14.

Benbasat, I., & Weber, R. (1996). Research commentary: Rethinking diversity in information systems

research. Information Systems Research, 7(4), 389-399.

Benbasat, I., & Zmud, R. W. (2003). The identity crisis within the IS discipline: Defining and communicating the disciplines core properties. MIS Quarterly, 27(2), 183-194.

Bennis, W. G. (1956). Some barriers to teamwork in social research. Social Problems, 3, 223-235.

Blyler, N. R. (1995). Research as ideology in professional communication. Technical Communication

Quarterly, 4(3), 285-313.

Boudreau, J., Hopp, W., McClain, J. O., & Thomas, L. J. (2003). On the interface between operations and

human resources management. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 5(3), 179-202.

Briggs, R. O., Nunamaker, J. F., Jr., & Sprague, R. (1999/2000). Special section: Exploring the outlands

of the MIS discipline. Journal of Management Information Systems, 16(3), 5-10.

Burke, K. (1984). Permanence and change: An anatomy of purpose (3rd ed.). Berkeley: University of

California Press.

Culnan, M. J. (1987). Mapping the intellectual status of MIS, 1980-1985: A Co-citation analysis. MIS

Quarterly, 11(3), 340-353.

Culnan, M. J., & Swanson, E. B. (1986). Research in management information systems, 1980-1984:

Points of work and reference. MIS Quarterly, 10(3), 289-302.

Davis, M. S. (1971). Thats interesting! Towards a phenomenology of sociology and a sociology of phenomenology. Philosophy of Social Science, 1, 309-344.

Dulek, R. E. (1993). Models of development: Business schools and business communication. Journal of

Business Communication, 30(3), 315-331.

Ede, L., & Lunsford, A. (1983). Why write . . . together? Rhetoric Review, 1(2), 150-157.

Ede, L., & Lunsford, A. (1990). Singular texts/Plural authors: Perspectives on collaborative writing.

Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Ferrara, K., Brunner, H., & Whittemore, G. (1991). Interactive written discourse as an emergent register.

Written Communication, 8(1), 8-34.

Fitzgerald, G. (2003). Information systems: A subject with a particular perspective, no more, no less.

European Journal of Information Systems, 12(3), 225-228.

Forman, J. (1991a). Computing and collaborative writing. In G. E. Hawisher & C. L. Selfe (Eds.), Evolving perspectives on computers and composition studies. (pp. 65-83). Urbana, IL: National Council of

Teachers of English.

Forman, J. (1991b). Novices work on group reports: Problems in group writing and in computersupported group writing. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 5(1), 48-75.

Forman, J. (1998). More than survival: The discipline of business communication and the uses of translation. Journal of Business Communication, 35, 50-68.

Forman, J. (2004). Opening the aperture: Research and theory on collaborative writing. Journal of Business Communication, 41, 27-36.

Forman, J., & Katsky, P. (1986). The group report: A problem in small group or writing processes? Journal of Business Communication, 23(4), 23-35.

Foucault, M. (1972). The discourse on language. In M. Foucault, The archaeology of knowledge & the

discourse on language (A. M. S. Smith, Trans., pp. 215-237). New York: Pantheon.

Galegher, J., Kraut, R. E., & Egido, C. (Eds.). (1990). Intellectual teamwork: Social and technological

foundations of cooperative work. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Graham, M. B., & Thralls, C. (1998). Guest editorial: Connections and fissures: Discipline formation in

business communication. Journal of Business Communication, 35, 7-13.

Henderson, G. V., Jr., Ganesh, G. K., & Chandy, P. R. (1990). Across-discipline journal awareness and

evaluation: Implications for the promotion and tenure process. Journal of Economics and Business,

42(4), 325-351.

102

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION

Klein, J. T. (1990). Interdisciplinarity: History, theory, & practice. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University

Press.

Latour, B., & Woolgar, S. (1979). Laboratory life: The social construction of scientific facts. Beverly

Hills, CA: Sage.

Locker, K. O. (1994). The challenge of interdisciplinary research. Journal of Business Communication,

31, 137-151.

Lowry, P. B., Curtis, A., & Lowry, M. R. (2004). Building a taxonomy and nomenclature of collaborative

writing to improve interdisciplinary research and practice. Journal of Business Communication,

41(1), 66-99.

Markus, M. L. (1992). Asynchronous technology in small face-to-face groups. Information Technology

& People, 6(1), 29-48.

Markus, M. L., & Connolly, T. (1990). Why CSCW applications fail: Problems in the adoption of interdependent work tools. In F. Halasz (Ed.), Proceedings of the Conference on Computer-Supported