Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Controlled Hyperventilation

Uploaded by

Anonymous Ybv0xbOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Controlled Hyperventilation

Uploaded by

Anonymous Ybv0xbCopyright:

Available Formats

WILDERNESS & ENVIRONMENTAL MEDICINE, ], ]]]]]] (2014)

Letter to the Editor

Controlled Hyperventilation After Training May

Accelerate Altitude Acclimatization

To the Editor:

On January 28, 2014, a group of 26 trekkers (aged 29 to

65 years), under the supervision of the authors, ascended

one of the worlds highest mountains (Mt. Kilimanjaro,

5895 m) in 48 hours (Figure 1). While doing so, the

group appears to have broken new medical ground,

utilizing a new method to largely prevent, and as needed,

reverse, symptoms of acute mountain sickness (AMS).

Seemingly an unlikely group of people for such a feat,

the group consisted of nonathletes with little or no prior

climbing experience, inhabitants of low altitudes, some

with typically handicapping diagnoses such as multiple

sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and metastasized cancer.

The team was predicted by mountaineering experts to

fail owing to those demographics. It was assessed at the

highest risk for exhaustion and altitude sickness due to

very rapid ascent (4500 m per day), high nal altitude

(44000 m), and unknown history of AMS (according to

a recent literature review).1

To offset these signicant disadvantages, the group

received special training, including mindset coaching,

cold exposure, and breathing technique practice, as

previously described and currently under investigation

by the authors.2 The trekkers used breathing techniques

(permanent controlled hyperventilation aimed at keeping

oxygen saturation (SpO2) greater than 90% during

the ascent both prophylactically and therapeutically.

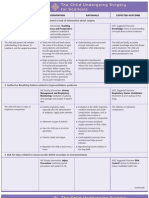

At regular intervals, all trekkers participated in 30minute breathing sessions, lled out a safety checklist

based on the Lake Louis Scoring System (LLSS

[Figure 2]) with a buddy, and were examined by the

medical doctor.3

The results were remarkable. First, the ascent is

typically completed by 61% of trekkers and takes 4 to 7

days.4 Of our group, 92% completed the ascent (2 had to

stop at 5681 m). Second, the group reached the summit

(5895 m) in only 48 hours. Third, none of the trekkers had

severe AMS following the LLSS nor reported symptoms

of hypocapnia due to the hyperventilation. None had used

any method of prevention other than the training and

techniques described above.3,4 The LLSS remained 4 or

less for 22 trekkers (mild AMS). Four had an LLSS of 5

or 6 (moderate AMS) at 1 check-up, and the LLSS

decreased to 4 or less after a 30-minute breathing session.

Two had clinical signs of physical/respiratory exhaustion

at 5681 m, which resolved after 15 minutes of oxygenation (12 L/min) and descent; of whom one had transient

Figure 1. Map of the Marangu route showing ascent versus time.

Letter to the Editor

mild hypothermia, and a third had suspected mild

high-altitude pulmonary edema (LLSS 5, pulse 97 beats/

min, SpO2 73%, respiratory rate 18 breaths/min, frothy

sputum, but absence of crepitations on auscultation of the

lungs) upon descent to a rest camp (3760 m), and it

resolved within 3 hours after oral administration of nifedipine 30 mg.

The technique used by the trekkers is named the Wim

Hof method, after the inventor who has been inspired by

Tummo meditation. First, by intense mindset coaching,

one can gain more condence in ones physical potential

and is continuously challenged to push physical boundaries and improve health control. Second, decreasing

pCO2 by controlled hyperventilation can stimulate this

Conquer Your Challenges - Safety Checklist

Name of Climber:

Time:

Al!tude (m):

Oxygen satura!on (%):

Pulse (beats/min):

Body temperature (C):

Symptoms:

1.Headache:

No headache 0

Mild headache 1

Moderate headache 2

Severe, incapacita!ng 3

2.GI:

No GI symptoms 0

Poor appe!te or nausea 1

Moderate nausea or vomi!ng 2

Severe N&V, incapacita!ng 3

3.Fa!gue/weak:

Not !red or weak 0

Mild fa!gue/weakness 1

Moderate fa!gue/weakness 2

Severe F/W, incapacita!ng 3

4.Dizzy/lightheaded:

Not dizzy 0

Mild dizziness 1

Moderate dizziness 2

Severe, incapacita!ng 3

5.Diculty sleeping:

Slept well as usual 0

Did not sleep as well as usual 1

Woke many !mes, poor night's sleep 2

Could not sleep at all 3

Clinical (Buddy) Assessment:

6.Change in mental status:

No change 0

Lethargy/lassitude 1

Disoriented/confused 2

Stupor/semiconsciousness 3

7.Ataxia(heel to toe walking):

No ataxia 0

Maneuvers to maintain balance 1

Steps o line 2

Falls down 3

Can't stand 4

8.Peripheral edema:

No edema 0

One loca!on 1

Two or more loca!ons 2

Total Lake Louise Criteria Score:

Mild AMS: score of <4

Moderate AMS: score of 5-6 (stop further ascent)

Severe AMS: score of 7 or more (descent)

Figure 2. The Acute Mountain Sickness Safety Checklist. AMS, acute mountain sickness; GI, gastrointestinal; F/W, fatigue/weakness; N&V,

nausea and vomiting.

Letter to the Editor

process as it improves endurance and enhances perceived

energy levels. Third, generation of body heat during

gradual cold exposure using breathing techniques is one

of the fundamental exercises of the method (Tummo).

The method seems to have a direct biological effect on

the autonomic nervous system, and warrants further

investigation.2

The exact pathophysiology of AMS remains unclear. In

the authors opinion, the severity and duration of hypobaric hypoxia play a key role. The remarkable results are

most likely explained by the continuous controlled

hyperventilation reducing hypoxia severity. However,

the resultant state of respiratory alkalosis may cause

symptoms such as dizziness and visual disturbances.

The fact that none of the trekkers experienced such

symptoms is most likely due to the long-term training.

In comparison with previous studies,4,5 this report

may suggest that acclimatization, as well as AMS

symptom relief, can be safely accelerated. Based on

previous data, it was expected that the majority of our

group would experience severe AMS. All 26 trekkers

had symptoms of AMS to some extent, but even without

prophylaxis, none had severe AMS. Even though we

discourage (very) rapid ascent because of potentially

lethal risks, we consider these outcomes of potentially

great relevance for the prevention and treatment of AMS,

as well as for rescue teams needing to ascend fast with

little time for acclimatization. Further research is warranted to expand or revise our understanding of the

physiology and treatment of these conditions.

Geert A. Buijze, MD, PhD

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery

Academic Medical Center Amsterdam

Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Maria T. Hopman, MD, PhD

Department of Physiology

University Medical Center Nijmegen

Nijmegen, The Netherlands

References

1. Brtsch P, Swenson ER. Clinical practice: acute highaltitude illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:22942302.

2. Kox M, van Eijk LT, Zwaag J, van den Wildenberg J,

Sweep FC, van der Hoeven JG, Pickkers P. Voluntary

activation of the sympathetic nervous system and attenuation of the innate immune response in humans. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:73797384.

3. Luks AM, McIntosh SE, Grissom CK, et al. Wilderness

Medical Society consensus guidelines for the prevention

and treatment of acute altitude illness. Wilderness Environ

Med. 2010;21:146155.

4. Davies AJ, Kalson NS, Stokes S, et al. Determinants of

summiting success and acute mountain sickness on Mt Kilimanjaro (5895 m). Wilderness Environ Med. 2009;20:311317.

5. Meyer J. Twice-daily assessment of trekkers on Kilimanjaros Machame route to evaluate the incidence and timecourse of acute mountain sickness. High Alt Med Biol.

2012;13:281284.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Pengaruh Faktor-Faktor Psikososial Dan Insomnia Terhadap Depresi Pada Lansia Di Kota YogyakartaDocument5 pagesPengaruh Faktor-Faktor Psikososial Dan Insomnia Terhadap Depresi Pada Lansia Di Kota YogyakartaKristina Puji LestariNo ratings yet

- Pe Lecture NotesDocument7 pagesPe Lecture NotesAnonymous LJrX4dzNo ratings yet

- 10th BIOLOGY PPT CH. NO. 8Document13 pages10th BIOLOGY PPT CH. NO. 8Aastha BorhadeNo ratings yet

- Auxin Controls Seed Dormacy in Arabidopsis (Liu, Et Al.)Document6 pagesAuxin Controls Seed Dormacy in Arabidopsis (Liu, Et Al.)Jet Lee OlimberioNo ratings yet

- Paragraph Development ExerciseDocument6 pagesParagraph Development ExerciseSYAFINAS SALAM100% (1)

- Hematology Analyzers, Coagulation Systems Product GuideDocument4 pagesHematology Analyzers, Coagulation Systems Product GuideElvan Dwi WidyadiNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia For The Pet Practitioner (2011 3rd Edition)Document216 pagesAnesthesia For The Pet Practitioner (2011 3rd Edition)Amela Dolittle Halilbašić100% (5)

- Fetal Circulation (For MBBS)Document50 pagesFetal Circulation (For MBBS)Tashif100% (1)

- 2018 Biology Exercises For SPM (Chapter6 & Chapter7)Document15 pages2018 Biology Exercises For SPM (Chapter6 & Chapter7)Kuen Jian LinNo ratings yet

- Wound CareDocument14 pagesWound CareKirsten Padilla Chua100% (4)

- GIT Physio D&R AgamDocument67 pagesGIT Physio D&R Agamvisweswar030406No ratings yet

- H2S Training Slides ENGLISHDocument46 pagesH2S Training Slides ENGLISHf.B100% (1)

- Body WeightDocument23 pagesBody WeightIkbal NurNo ratings yet

- Aids 2013Document404 pagesAids 2013kovaron80No ratings yet

- Lim Et Al 2017 PDFDocument37 pagesLim Et Al 2017 PDFkirshNo ratings yet

- Bulacan State University College of Nursing Final Exam ReviewDocument7 pagesBulacan State University College of Nursing Final Exam ReviewDemiar Madlansacay QuintoNo ratings yet

- BioSignature Review - Are Hormones The Key To Weight LossDocument19 pagesBioSignature Review - Are Hormones The Key To Weight LossVladimir OlefirenkoNo ratings yet

- The Management of Intra Abdominal Infections From A Global Perspective 2017 WSES Guidelines For Management of Intra Abdominal InfectionsDocument34 pagesThe Management of Intra Abdominal Infections From A Global Perspective 2017 WSES Guidelines For Management of Intra Abdominal InfectionsJuan CastroNo ratings yet

- AP PSYCHOLOGY EXAM REVIEW SHEETDocument6 pagesAP PSYCHOLOGY EXAM REVIEW SHEETNathan HudsonNo ratings yet

- Assignment Lec 4Document3 pagesAssignment Lec 4morriganNo ratings yet

- Electrolyte Imbalance 1Document3 pagesElectrolyte Imbalance 1Marius Clifford BilledoNo ratings yet

- Arthropod-Plant Interactions Novel Insights and Approaches For IPMDocument238 pagesArthropod-Plant Interactions Novel Insights and Approaches For IPMAnonymous T9uyM2No ratings yet

- Pancoast Tumour: Rare Lung Cancer FormDocument2 pagesPancoast Tumour: Rare Lung Cancer FormobligatraftelNo ratings yet

- Modul Strategik Bab 1 Ting 5Document6 pagesModul Strategik Bab 1 Ting 5SK Pos TenauNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document7 pagesChapter 4R LashNo ratings yet

- NURSING CARE PLAN The Child Undergoing Surgery For ScoliosisDocument3 pagesNURSING CARE PLAN The Child Undergoing Surgery For ScoliosisscrewdriverNo ratings yet

- Nicotrol InhalerDocument19 pagesNicotrol InhalerdebysiskaNo ratings yet

- Blood TransfusionDocument6 pagesBlood TransfusionRoxanne Quiñones GelacioNo ratings yet

- Anatomy 2ND de BachilleratoDocument24 pagesAnatomy 2ND de BachilleratoAlexander IntriagoNo ratings yet

- Abbreviation For ChartingDocument12 pagesAbbreviation For ChartingJomar De BelenNo ratings yet