Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Treatment of Claustrophobia

Uploaded by

vinodksahuCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Treatment of Claustrophobia

Uploaded by

vinodksahuCopyright:

Available Formats

CyberPsychology & Behavior

Volume 2, Number 2, 1999

Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.

Claustrophobia with Virtual Reality:

The Treatment of

Changes in Other Phobic Behaviors Not

Specifically Treated

C. BOTELLA,

Ph.D.,1

H.

BAOS, Ph.D.,2 C. PERPI, Ph.D.,2

GARCA-PALACIOS, Ph.D.1

VILLA,1

and A.

R.

ABSTRACT

This study was designed to determine the effectiveness of Virtual Reality (VR) exposure in

the case of a patient with a diagnosis of two specific phobias (claustrophobia and storms) and

panic disorder with agoraphobia. The treatment consisted of eight, individual, VR-graded ex

posure sessions designed specifically to treat claustrophobia. We obtained data at pretreat

ment, posttreatment, and 3-month follow-up on several clinical measures. Results point out

the effectiveness of the VR procedure for the treatment of claustrophobia. An important

change appeared in all measures after treatment completion. We also observed a generaliza

tion of improvement from claustrophobic situations to the other specific phobic and agora

phobic situations that were not treated. We can conclude that VR exposure was effective in

reducing fear in closed spaces, in increasing self-efficacy in claustrophobic situations, and in

improving other problems not specifically treated. Moreover, changes were maintained at 3

months after treatment.

INTRODUCTION

the treatment of choice for

has been in vivo

exposure;1'2 however, not patients can ben

efit from this treatment. Some patients are too

afraid of facing the threatening object or con

text and they reject an exposure program or

they drop out.3 Even for the patients who ac

cept the treatment, this can be difficult. Patients

with phobias do not feel safe because there is

no certainty for them that something will not

go wrong (e.g., elevator stoppage, technical

Traditionally,

treating specific phobias

all

lTJniversitat Jaume I, Department Psicologia Basica,

Psicobiologia, Castelln, Spain.

2Universidad de Valencia, Department de Personali

dad, Evaluacin y Tratamiento Psicolgicos, Valencia,

Clinica y

Spain.

In the last few

years, several studies have been published that

describe the utility of virtual reality (VR) tech

problems in the airplane, etc.).

niques for the treatment of phobias: acropho

bia,4-7 arachnophobia,8 flying phobia,9 agora

phobia,4 and claustrophobia.10

As Wiederhold11 points out, numerous pub

lications from at least 15 centers around the

world state that the treatment of specific pho

bias using VR is not only effective, but it also

has a number of advantages when compared

with traditional treatments. First, VR provides

safety to the patient because the virtual envi

ronment can be absolutely graded in regards to

the suitable degree of difficulty for the pa

tient.10 Second, VR becomes a useful tool in

cases where the feared situation is not easily

accessible (e.g., in an airplane).10 And finally,

some patients who follow an exposure pro135

BOTELLA ET AL.

136

gram continue to manifest "residual fears."3

We think that the control provided by VR en

vironments and the possibility of going beyond

what a "real" situation would allow are factors

that can promote patients' feelings of self-effi

cacy and help to eliminate the residual fears.

Although evidence exits on the utility of VR

for the treatment of specific phobias, the stud

ies carried out until now have applied VR tech

airplanes. She suffered an unexpected

panic attack while on vacation far from home

sessment.

test. It measured

and

(500 KM). (She went to an emergency room in

hospital.) Since then, she began to develop

agoraphobic avoidance, which was evident in

her inability to travel to unknown places and

shop alone.

a

Measures

niques to patients who were not very impaired

by the phobia. There are some exceptions, as in Admission interview. Through this interview,

the Carlin et al.8 study where the patient was demographic and clinical information is ob

tained. During the interview, the patient is also

severely impaired by her arachnophobia.

The purpose of the present study was to de asked some questions to determine the pres

termine the effectiveness of VR exposure de ence of different anxiety disorders. The patient

signed to treat claustrophobia in a patient who, is also asked about each criteria of DSMbesides the diagnosis of claustrophobia, also IV-specific phobia, situational type.

suffered from another specific phobia (natural

Behavioral Avoidance Test (BAT). Avoidance

type: storms) and panic disorder with agora of closed spaces was assessed using a behav

phobia. We included a 3-month follow-up as ioral avoidance test. A closet was built for this

(75

cm

The patient was asked to enter the

closet and stay there for 5 minutes with the

door locked. The patient could terminate the

Lest at any moment and could also refuse to en

ter the closet if she considered that she was go

ing to experience more anxiety than was bear

able. The test ended 5 minutes after its

initiation unless the patient had stopped the

test before this time. Before the commencement

of the test, the patient answered some ques

tions about what she thought was going to hap

pen during the test. The measures used during

this test were expected danger, expected fear,

expected self-efficacy, and subjective fear. The

patient rated these variables using 10-point

scales. The therapist also measured the degree

of avoidance in the BAT. The range of the

scores was from 0 to 13. The score was obtained

as follows: 0

refused to enter, 1 went in,

2 closed the door but did not turn the key,

3 closed the door with key. Afterwards, 0.25

points were added for each period of 30 sec

onds that the patient stayed inside the closet

with the door open, 0.50 points for each period

of 30 seconds that the patient stayed inside with

the door closed but not locked, and 1 point for

each period of 30 seconds that the patient

stayed inside with the door locked. The high

height).

METHOD

Participant

The participant was a patient who asked for

help in the Jaume I University Anxiety Disor

ders Clinic. The patient met DSM-IV criteria for

two specific phobias, situational type (claus

trophobia), and natural environment type

(storms). She also met the criteria of panic dis

agoraphobia. She had received no

prior treatment for psychological problems.

She signed a consent form. An independent as

order with

reviewed the assessment and confirmed

the presence or absence of panic disorder (with

or without agoraphobia) and other diagnoses.

The patient was a 37-year-old female laun

dress who was married with two children. She

experienced fear of closed spaces (elevators,

buses, crowds, planes). The onset of the prob

lem occurred when a crowd surged toward her

in a sales mall 12 years prior. As a consequence

of that event, she also developed a specific

phobia, natural environment type (storms), be

cause what caused the avalanche of people

was a big storm. One year after the incident

she began to fear crowds, being enclosed in an

elevator, reduced spaces, tunnels, traffic jams,

sessor

slightly less than an elevator

m in length X 2 m in

in width X 1

est

score was

13.

137

CLAUSTROPHOBIA AND VIRTUAL REALITY

Fear record: A Spanish adaptation of the Mars

and Mathews12 scales. The target behavior was

assessed according to the degree of fear, from

0 to 10, where 0 was "no fear" and 10 was "ex

treme fear."

Subjective units of discomfort scale (SUDS).13

The participant rated his maximum level of

anxiety on a 10-point scale before the BAT,

while he/she was in the closet and after the

BAT. We also used this measure during the ex

posure sessions.

Problem-related impairment questionnaire.13

This instrument evaluated the impairment that

the disorder caused in several areas of the pa

tient's life. Each area was rated on a 10-point

scale with scores ranging from 0 (Not at all) to

10 (Completely). Only global impairment was

analyzed in this study.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)14 adapted

by TEA (1988) for the Spanish population. The

Anxiety Trait is defined as a relatively stable

anxiety apprehension by which those partici

pants differ in their tendency to perceive situ

ations as threatening and to increase, conse

quently, their state of anxiety.

The Anxiety Sensitivity Index (AST).15 This is

a measure of anxiety sensitivity, which Reiss et

al.15 have defined as "an individual difference

variable consisting in the belief that the expe

rience of anxiety causes illness, embarrassment

or additional anxiety." We use a Spanish ver

sion of the ASI16 adapted by Sandin, Chorot,

and McNally.17

Apparatus

A Silicon Graphics

Indigo High Impact com

a high quality

head-mounted display (FS5 from Virtual Re

search) and an electromagnetic sensor were

used to track the head and right hand (Fastrak

system from Polhemus). Modeling was done

puter graphics workstation,

with Autocad version 13 software (Autodesk,

Ine). To obtain realistic virtual environments, a

special technique of texture-mapping genera

tion was used. The virtual environment was

rendered with radiosity techniques using

Lightscape version 3.0 software (Lightscape

Technologies). Once the visual environment ra

diosity solutions had been calculated, the Dvise

version 3.0 (Division Ine) was used to create the

virtual environment from the models. In this

model, the texture generated from radiosity so

lutions was mapped on the geometry models,

thus obtaining a highly realistic virtual envi

ronment.

Virtual environment

graduate the levels of difficulty of the

"claustrophobic" environment, two different

settings were created. The first of them was a

house (Figs. 1 and 2) and the second one was

an elevator (Fig. 3). In each setting, several dif

To

ferent environments existed that allowed for

the building of hierarchies with degrees of in

creasing difficulty. The virtual environments

are described in Botella et al.10

FIG. 1.

138

BOTELLA ET AL.

FIG. 2.

Procedure

period.

The patient attended two assessment ses

sions in which the Admission Interview, as

well as the self-report instruments described

earlier, were administered. During the second

assessment session, the patient was asked to

provide self-efficacy ratings for coping in a

closed space created especially for a BAT. She

was asked to rate how sure she was that she

would be able to stay in a closet for at least 5

minutes, and she scored herself by circling a

number from 0 to 10. At the end of the second

session, the patient was also provided with the

fear record. The patient was instructed to mon

itor her fear of a claustrophobic target behav

ior on a 10-point scale during a 15-day baseline

asked to record this informa

basis

daily

during the baseline period

and throughout the entire process. The fear

record was reviewed at the beginning of each

subsequent session, and difficulties in moni

toring were addressed. She fulfilled the self-re

port measures at the end of the treatment and

at a follow-up session 3 months after treatment.

She

was

tion on a

Treatment

A total of eight sessions of VR-graded expo

sessions were carried out over 30 days. VR

was conducted for

approximately 35^5 min

utes in each session. A video monitor allowed

the therapist to observe the virtual environ

sure

ments to which

FIG. 3.

the

patient was exposed.

The

139

CLAUSTROPHOBIA AND VIRTUAL REALITY

10

'

6-1

2

"T~"T^**f*~T**T

B-Line

Treatment

Pst

FIG. 4.

therapist's instructions in the VR sessions were

similar to those used in conventional in vivo

exposure. The therapist encouraged the patient

to interact with the environment long enough

for her anxiety to decrease. Their anxiety level

(SUDS18) was assessed every 5 minutes.

RESULTS

Results of the fear record are shown in Fig

ure 4. The treatment brought about an impor

tant decrease in the fear toward closed spaces

and in the interference of the claustrophobia in

the patient's life. These outcomes not only were

maintained but also improved 3 months later.

The results from the other measures are

shown in Table 1. The BAT scores showed an

important change in the avoidance toward

closed spaces, because the patient changed

from not being able to complete the BAT (be

fore the treatment) to completely achieving the

goals of the test after completion of treatment.

A clear improvement in alLthe measures of the

BAT was obtained. The expected danger and

Table 1.

Behavior Avoidance Test

Measures

the expected fear decreased, and the self-effi

cacy in the feared situation increased. The de

gree of fear reported also decreased. The results

regarding the self-report measures showed also

a decrease in global impairment and anxiety

sensitivity (ASI) upon completion of treatment.

In these measures, changes were maintained at

3-months follow-up. Finally, general trait anx

iety (STAI-T) also decreased, although this

decrement did not occur until 3-months fol

low-up.

DISCUSSION

Our findings support the clinical effective

ness of VR exposure for treating claustropho

bia. The treatment was effective in decreasing

the fear and avoidance to claustrophobic situ

ations and the interference of the problem, and

the achievements were maintained at 3-months

follow-up. This data support the results of our

previous case study.10 Moreover, VR was used

alone as the sole technique, and it was applied

to a patient with not only a diagnosis of spe-

(BAT)

and

Self-Report Measures

Pretreatment

Posttreatment

Follow-up

10

10

0

9

4

34

33

3

3

7

0

13

25

30

7

1

1

8

0

13

18

23

5

BAT

Expected danger

Expected fear

Expected self-efficacy

Subjective fear

Behavioral avoidance

ASI

STAI-T

Interference

140

BOTELLA ET AL.

phobia, but also with PDAG, which im agoraphobia and panic disorder with agora

plies a higher degree of severity. VR would phobia. Our team is currently addressing this

cific

therefore appear to be very useful in

thera

peutic perspective.19,20

The treatment by means of VR achieved gen

eralization to other behaviors which were not

specifically treated. The patient achieved an

important improvement in her fear of storms,

a problem which, apparently, had nothing to

do with claustrophobia. She also began to go

alone to places which she had previously

avoided because of her agoraphobia (going to

pick up the children from school, going shop

ping alone, taking the bus to work). Finally, her

fear of getting trapped in a traffic jam de

creased significantly.

Regarding self-efficacy measures, our data

also support our premise that VR may be an ex

cellent source of information in the field of per

formance outcomes10,19-21 because the patient

showed an important change in the self-efficacy

with closed spaces. This issue could be one of

the reasons why the improvement generalized

to other problems not specifically treated. The

patient reported that the treatment helped her

to feel more capable to face feared situations in

general, not only claustrophobic situations.

Another issue related with generalization are

the results from the ASI. The score of the par

ticipant before the treatment was very high. Ac

cording to data from Spanish samples,17 the pa

tient was situated in the range of scores of

people with a diagnosis of panic disorder.

These data indirectly support the current ap

proach on the construct of anxiety sensitivity

(i.e., this construct is more strongly associated

to panic disorder than to other anxiety disor

ders).22'23 On the other hand, there was an im

portant decrease in the score of the patient af

ter completion of the treatment. We think that

this finding is encouraging because the condi

tion of the patient could be considered as se

vere, and the only treatment that she received

was VR exposure to claustrophobic scenarios.

The fact of generalization of improvement to

other aspects not specifically treated and the

change observed in many agoraphobic behav

iors that the patient presented, brings us to be

lieve that the extension and enlargement of the

scenarios created by VR can be very helpful in

the treatment of such an important problem as

issue.

In summary, our data indicates that VR ex

posure is a useful procedure in the treatment

of claustrophobia. Moreover, outcomes can be

generalized to other problems with higher de

grees of severity than agoraphobia. However,

we would like to exercise caution in our state

ments regarding the effectiveness of VR be

cause most of the work in this field is still to be

done. It will be necessary to study and analyze

VR's usefulness in the treatment of other psy

chological disorders, and include larger sam

ples given the fact that most studies in this field

are case studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This paper was partially sponsored by the

Conselleria de Cultura, Educaci i Ciencia

(Generalitt Valenciana) (Ministry of Educa

tion and Science) (GV-D-ES-17-123-96), the

Instituto de la Mediana y Pequea Industria

de la Generalitt Valenciana (EMPIVA) (In

stitute of Small and Mid-sized Businesses)

(971801003556), and FEDER funds (1FD97-

0260-C02-01).

REFERENCES

Marks, I.M. (1987). Fears, phobias and rituals. New

York: Oxford University Press.

2. Ost, L.G. (1987). Age of onset in different phobias.

Journal of abnormal Psychology, 96, 223-229.

3. Marks, I.M., and O'Sullivan, G. (1992). Psicofrmacos

y tratamientos psicolgicos en la agorafobia/pnico

y en los trastornos obsesivo-compulsivos. In E.

Echebura (Ed.). Avances en el tratamiento psicolgico

de los trastornos de ansiedad. Madrid: Pirmide.

1.

4.

Rothbaum, ., Hodges, L., Kooper, R., Opdyke, D.,

Williford J., and North, M. (1995). Effectiveness of

computer generated (virtual reality) graded exposure

in the treatment of

5.

acrophobia. American Journal of

Psychiatry, 152, 626-628.

Rothbaum, V.O., Hodges, L.F., Kooper, R., Opdyke,

D., Williford, J.S., and North, M. (1995). Virtual-real

ity graded exposure in the treatment of acrophobia

case report. Behaviour Therapy, 26(3), 547-554.

North, M., and North, S. (1994). Virtual environments

and psychological disorders. Electric Journal of Virtual

Culture, 2(4), 25-34.

A

6.

CLAUSTROPHOBIA AND VIRTUAL REALITY

7.

North, M., and North, S. (1996). Virtual reality psy

chotherapy. The Journal of Medicine and Virtual Reality,

17.

Virtual reality and tactile augmentation in the treat

ment of spider phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy,

35, 153-158.

18.

Rothbaum, V.O., Hodges, L., Watson, B.A., Kessler,

G.D., and Opdyke, D. (1996). Virtual reality exposure

19.

1, 28-32.

8. Carlin, A.S., Hoffman, H.G., and Weghorst, S. (1997).

9.

141

therapy in the treatment of fear of flyingA case re

port. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34(5-6), 477-481.

10. Botella, C, Baos, R.M., Perpi, G, Villa, H., Alcaiz,

M., and Rey, . (1998). Virtual reality treatment of

claustrophobia: A case report. Behaviour Research and

Therapy, 36, 239-246.

11. Wiederhold, M.D. (1998). Preface. In G. Riva, B.K.

Wiederhold, and E. Molinari (Eds.). Virtual environ

ments in clinical psychology and neuroscience. Amster

dam: IOS Press.

12. Marks, I.M., and Mathews, A. (1979). Brief standards

self-rating for phobic patients. Behaviour Research and

Therapy, 17, 263-267.

13. Wolpe, J. (1969). The practice of behavior therapy. New

York: Pergamon.

14. Borda, M., and Echebura, E. (1991). La autoexposicin como tratamiento psiolgico en un caso de ago

rafobia. Anlisis y Modificacin de Conducta, 18,

101-103.

15. Spielberger, G, Gorsuch, R., Luschene, R., Vagg, P.,

and Jacobs, G. (1983). Manual for the state-trait anxi

ety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist

Press.

16. Reiss, S., Peterson, R., Gursky, D., and McNally, R.

(1986). Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the

prediction of fearfulness. Behaviour, Research and Ther

apy, 24, 1-8.

20.

21.

22.

Sandin, B., Chorot, P., and McNally, R.J. (1996). Val

idation of the Spanish version of the Anxiety Sensi

tivity Index in a clinical sample. Behaviour Research and

Therapy, 34, 283-290.

Peterson, R.A., and Reiss, S. (1992). Anxiety sensitivity

index manual (2nd ed.). Worthington, OH: Interna

tional Diagnostic Systems.

Botella, C, Baos, R.M., Perpi, G, and Garca-Pala

cios, . (1998). Virtual reality: A new clinical setting

lab. In G. Riva, B.K. Wiederhold, and E. Molinari

(Eds.). Virtual environments in clinical psychology and

neuroscience. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Botella, C, Baos, R.M., Perpi, C, and Ballester, R.

(1998). Realidad virtual y tratamientos psicolgicos,

Anlisis y Modificacin de Conducta, 24, 5-26.

Bandura, . (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying

theory of behavior change. Psychological Review, 84,

191-215.

McNally, R.J. (1991). Psychological approaches to

panic disorder: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 108,

403-419.

23.

McNally, R.J. (1994). Panic disorder: A critical analysis.

New York: Guilford Press.

Address reprint requests to:

Cristina Botella, Ph.D.

Universitt Jaume I

Department Psicologia Basica

Clinica y Psicobiologia

Borriol.

Ctra. Borriol s/n

Campus

12080 Castelln, Spain

E-mail: botella@psb.uji.es

This article has been cited by:

1. Helene S. Wallach, Marilyn P. Safir, Roy Samana. 2010. Personality variables and presence. Virtual Reality 14:1, 3-13.

[CrossRef]

2. Stphane Bouchard, Sophie Ct, David C.S. RichardVirtual reality applications for exposure 347-388. [CrossRef]

3. David C.S. Richard, Dean Lauterbach, Andrew T. GlosterDescription, mechanisms of action, and assessment 1-28.

[CrossRef]

4. Kate Cavanagh, David A. Shapiro. 2004. Computer treatment for common mental health problems. Journal of Clinical

Psychology 60:3, 239-251. [CrossRef]

5. Brenda K. Wiederhold , Mark D. Wiederhold . 2003. Three-Year Follow-Up for Virtual Reality Exposure for Fear of Flying.

CyberPsychology & Behavior 6:4, 441-445. [Abstract] [Full Text PDF] [Full Text PDF with Links]

6. Thomas G. Plante, Arianna Aldridge, Denise Su, Ryan Bogdan, Martha Belo, Kamran Kahn. 2003. Does Virtual Reality

Enhance the Management of Stress When Paired With Exercise? An Exploratory Study. International Journal of Stress

Management 10:3, 203-216. [CrossRef]

7. C. Botella , R. Baos , V. Guilln , C. Perpia , M. Alcaiz , A. Pons . 2000. Telepsychology: Public Speaking Fear Treatment

on the Internet. CyberPsychology & Behavior 3:6, 959-968. [Citation] [Full Text PDF] [Full Text PDF with Links]

You might also like

- Musical ObsessionsDocument61 pagesMusical ObsessionsvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy On Premature Ejaculation in An Iranian SampleDocument13 pagesEffectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy On Premature Ejaculation in An Iranian SamplevinodksahuNo ratings yet

- 2013 Draft BillDocument73 pages2013 Draft Billbluetooth191No ratings yet

- Aids ManiaDocument3 pagesAids ManiavinodksahuNo ratings yet

- CBT in DhatDocument8 pagesCBT in DhatvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- Disability Assessment in Mental Illnesses Using Indian Disability Evaluation Assessment Scale (IDEAS)Document5 pagesDisability Assessment in Mental Illnesses Using Indian Disability Evaluation Assessment Scale (IDEAS)vinodksahu100% (1)

- 1311Document6 pages1311Ahmed El AlfyNo ratings yet

- Claustrophobia VRDocument8 pagesClaustrophobia VRvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- Hormonal Correlations of Premature EjaculationDocument6 pagesHormonal Correlations of Premature EjaculationvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- Breast Cancer SurvivorsDocument30 pagesBreast Cancer Survivorsvinodksahu100% (1)

- BRCADocument7 pagesBRCAvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- Susanne Bengesser - Genetics of Bipolar DisorderDocument227 pagesSusanne Bengesser - Genetics of Bipolar Disordervinodksahu100% (1)

- Breast Cancer ActivismDocument6 pagesBreast Cancer ActivismvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Cancer Patients Engaging in Complimentary TherapiesDocument53 pagesBenefits of Cancer Patients Engaging in Complimentary TherapiesvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- The Evolving Epidemiology of HIV AIDS.9Document9 pagesThe Evolving Epidemiology of HIV AIDS.9vinodksahuNo ratings yet

- Breast Cancer TrreatmentDocument10 pagesBreast Cancer TrreatmentvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- BMJ Open-2014-Chang PDFDocument9 pagesBMJ Open-2014-Chang PDFvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- Depression and Health Related Quality of Life in Breast Cancer PatientsDocument4 pagesDepression and Health Related Quality of Life in Breast Cancer PatientsvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- Special Article: Words: Psycho-Oncology, Cancer, Multidisciplinary Treatment Approach, AttitudesDocument16 pagesSpecial Article: Words: Psycho-Oncology, Cancer, Multidisciplinary Treatment Approach, AttitudeshopebaNo ratings yet

- Crucial Conversations Book Discussion QuestionsDocument2 pagesCrucial Conversations Book Discussion Questionsvinodksahu83% (12)

- Anatomical Organization of The Eye FieldsDocument11 pagesAnatomical Organization of The Eye FieldsvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- Temperament and EvolutionDocument35 pagesTemperament and EvolutionvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- How To Confront The Workplace BullyDocument1 pageHow To Confront The Workplace BullyvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- Life-Changing Crucial Conversations SummaryDocument1 pageLife-Changing Crucial Conversations SummaryvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- Holding Slacking Coworkers Accountable SummaryDocument1 pageHolding Slacking Coworkers Accountable SummaryvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- Crucial Conversations For Women in Business SummaryDocument1 pageCrucial Conversations For Women in Business Summaryvinodksahu100% (1)

- Weighty Crucial Conversations With Your Child SummaryDocument1 pageWeighty Crucial Conversations With Your Child SummaryvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- Holding Slacking Coworkers Accountable DataDocument4 pagesHolding Slacking Coworkers Accountable DatavinodksahuNo ratings yet

- Four Crucial Conversations For Uncertain Times SummaryDocument1 pageFour Crucial Conversations For Uncertain Times SummaryvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Reading The Bible From Feminist, Dalit, Tribal and Adivasi Perspectives (Course Code: BC 107)Document8 pagesReading The Bible From Feminist, Dalit, Tribal and Adivasi Perspectives (Course Code: BC 107)Arun Stanley100% (2)

- Risk Factors of Oral CancerDocument12 pagesRisk Factors of Oral CancerNauman ArshadNo ratings yet

- CNL DivisionDocument38 pagesCNL DivisionaniketnareNo ratings yet

- Artikel 8 - (CURRICULUM EVALUATION)Document12 pagesArtikel 8 - (CURRICULUM EVALUATION)Kikit8No ratings yet

- My Initial Action Research PlanDocument3 pagesMy Initial Action Research PlanKarl Kristian Embido100% (8)

- Course: Consumer Behaviour: Relaunching of Mecca Cola in PakistanDocument10 pagesCourse: Consumer Behaviour: Relaunching of Mecca Cola in PakistanAnasAhmedNo ratings yet

- Healthy Body CompositionDocument18 pagesHealthy Body CompositionSDasdaDsadsaNo ratings yet

- ABS CBN CorporationDocument16 pagesABS CBN CorporationAlyssa BeatriceNo ratings yet

- UKAYUNIK Chapter 1 To 12Document31 pagesUKAYUNIK Chapter 1 To 12Chiesa ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Final Project Report by Himanshu Yadav Student of Fostiima Business SchoolDocument55 pagesFinal Project Report by Himanshu Yadav Student of Fostiima Business Schoolak88901No ratings yet

- History of Nursing: Nursing in The Near EastDocument7 pagesHistory of Nursing: Nursing in The Near EastCatherine PradoNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument45 pagesUntitledjemNo ratings yet

- Graphs in ChemDocument10 pagesGraphs in Chemzhaney0625No ratings yet

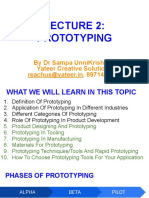

- Prototyping: by DR Sampa Unnikrishnan Yateer Creative Solutions Reachus@Yateer - In, 8971442777Document70 pagesPrototyping: by DR Sampa Unnikrishnan Yateer Creative Solutions Reachus@Yateer - In, 8971442777ShivashankarNo ratings yet

- CATL 34189-20AH Low Temperature Cell SpecificationDocument17 pagesCATL 34189-20AH Low Temperature Cell Specificationxueziying741No ratings yet

- Business Communication MCQ PDFDocument54 pagesBusiness Communication MCQ PDFHimanshu ShahNo ratings yet

- 4 Qi Imbalances and 5 Elements: A New System For Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument5 pages4 Qi Imbalances and 5 Elements: A New System For Diagnosis and Treatmentpixey55100% (1)

- Tuan Nor Akmal Imanina Binti Tuan MasorDocument2 pagesTuan Nor Akmal Imanina Binti Tuan MasorIzza RosliNo ratings yet

- Consumer Perception Towards WhatsappDocument72 pagesConsumer Perception Towards WhatsappRaj KumarNo ratings yet

- Three Moment Equation For BeamsDocument12 pagesThree Moment Equation For BeamsRico EstevaNo ratings yet

- Sheiko 13week Beginner ProgramDocument16 pagesSheiko 13week Beginner ProgramAnders DahlNo ratings yet

- The Mystery of Putins DissertationDocument16 pagesThe Mystery of Putins DissertationDoinaCebanuNo ratings yet

- Commissioning 1. Commissioning: ES200 EasyDocument4 pagesCommissioning 1. Commissioning: ES200 EasyMamdoh EshahatNo ratings yet

- Buzan, Barry - Security, The State, The 'New World Order' & BeyondDocument15 pagesBuzan, Barry - Security, The State, The 'New World Order' & Beyondyossara26100% (3)

- Al-Ahbash Evolution and BeliefsDocument4 pagesAl-Ahbash Evolution and BeliefskaptenzainalNo ratings yet

- Data Processing and Management Information System (AvtoBərpaEdilmiş)Document6 pagesData Processing and Management Information System (AvtoBərpaEdilmiş)2304 Abhishek vermaNo ratings yet

- School Earthquake Preparedness Evaluation FormDocument2 pagesSchool Earthquake Preparedness Evaluation FormAdrin Mejia75% (4)

- Research PaperDocument14 pagesResearch PaperNeil Jhon HubillaNo ratings yet

- NCS V5 1.0 Layer Name FormatDocument4 pagesNCS V5 1.0 Layer Name FormatGouhar NayabNo ratings yet

- CH 6 Answers (All) PDFDocument29 pagesCH 6 Answers (All) PDFAhmed SideegNo ratings yet