Professional Documents

Culture Documents

College Readiness

Uploaded by

MyDocumateCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

College Readiness

Uploaded by

MyDocumateCopyright:

Available Formats

College Readiness

Running Head: COLLEGE READINESS AND FIRST-GENERATION COLLEGE STUDENTS

Defining College Readiness from the Inside Out:

First-Generation College Student Perspectives

Kathleen Byrd, M. Ed.

Developmental Education Reading and English Instructor

South Puget Sound Community College

132 Plymouth St. N.W., Olympia, WA 98502

kathb@u.washington.edu. (360) 754-2889

Ginger MacDonald, Ph.D.

Director and Professor of Education

University of Washington, Tacoma

1900 Commerce Street, WCG 324, Tacoma, WA 98402

gmac@u.washington.edu. (253) 692-5690

College Readiness

Running Head: COLLEGE READINESS AND FIRST-GENERATION COLLEGE STUDENTS

Defining College Readiness from the Inside Out:

First-Generation College Student Perspectives

College Readiness

Abstract

This study provides understanding of college readiness from the perspectives of older firstgeneration college students, transferred from community college. Results indicate life

experiences contribute to academic skills, time management, goal focus, and self-advocacy.

Research is recommended to improve nontraditional student advising and placement, community

college-to-university transfer, and college reading instruction.

College Readiness

Defining College Readiness from the Inside Out:

First-Generation College Student Perspectives

College readiness is one of seven national education priorities (U. S. Department of

Education, 2000). Meanwhile, according to McCabe (2000) in a national study of community

college education, 41% percent of entering community college students and 29% of all entering

college students are underprepared in at least one of the basic skills of reading, writing, and

math. Since the 1980s, colleges have increasingly required placement testing to determine

college readiness and offered or required developmental or remedial education for students

placing below college level (Amey & Long, 1998; King, Rasool, & Judge, 1994). While the rise

in developmental programs and courses at community colleges might indicate that the problem

of underpreparedness is growing, underpreparedness for college-level work is not a new

phenomenon; rather it is a historical problem (Maxwell, as cited in Platt, 1986).

Even as a college education becomes increasingly imperative for social and economic

success (Day & McCabe, 1997; Lavin, 2000; Ntiri, 2001), access to college is problematic for

nontraditional or high-risk students. This situation is due to issues of academic, social, and

economic readiness (Hoyt, 1999; Valadez, 1993). Increasingly, decisions about college readiness

are made by standardized assessments. In the recent past, some colleges maintained open

enrollment policies that allowed nontraditional students to enter the system, but that is changing.

Standardized-test-based admissions may overlook nontraditional students historical and cultural

background that might include strengths as well as deficits related to readiness for college.

This study explored the nature of college readiness from the perspectives of firstgeneration college students. The participants of this study had transferred to a university from a

community college, were older than 25, and were of a first generation in their families to attend

College Readiness

college. From the standpoint of successful degree-seeking students who fit this definition of

nontraditional, the researchers explored these four general questions: (a) What does it mean to be

ready for college? (b) What do successful nontraditional students bring to their college

experiences that contribute to their success? (c) How can nontraditional learners be seen to have

strengths and not just deficits? and, (d) How are students prepared or not prepared for college in

ways not measured by standardized tests?

Prediction and College Readiness

College readiness involves prediction. Placement tests and other standardized measures

are often used to predict students readiness for college. Armstrong (1999) and King et al (1994)

concluded that the predictive value of standardized placement tests is questionable. In addition,

Armstrongs (1999) study showed little or no relationship between [placement] test scores and

student performance in class (p. 36). This current study attempts to explore the challenge set

forth by King et al. (1994): If scores do not predict success, then we must consider alternative

explanations for student success (p. 7).

Developmental Education Programs

Developmental education courses at community colleges help to provide underprepared

students with math, reading and English and study skills to succeed in college. Research findings

from studies conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of such programs are predominately positive

(Amey & Long, 1998; Hennessey, 1990; Hoyt, 1999; Kraska, Nadelman, Maner, & McCormick,

1990; Napoli & Hiltner, 1993). However, questions of college-readiness, even as students enter

and exit developmental education courses, remain (Hoyt, 1999). Boylan, Bliss, and Bonham,

(1997) conducted a meta-analysis of developmental programs that included consideration of

mandatory assessment and placement on the success and retention of college students. They

College Readiness

found that while mandatory assessment and placement were not found to impact overall retention

rates or grade point average, these factors did affect student success within developmental

courses.

Hoyt (1999) conducted a study to examine the influence of student need for remediation

on retention rates at a community college. Based on that study, Hoyt concluded that predicting

retention for under-prepared students is difficult because of the many factors involved. However,

the study indicated that first-term academic performance had the strongest relationship to

retention, followed by student receipt of financial aid. As a result of that study, Hoyt (1999)

emphasized the need for interventions that focus on the academic needs of students and for

strengthening financial aid programs, particularly for high-risk students.

Hennessy (1990) found that students who successfully completed a reading improvement

course were more likely to be successful in college classes. Hennessy speculated two possible

causes for their success. One possible factor was that participation in the reading course led to

student success, or the second possibility that Hennessy (1990) raises is that those who heeded

their counselors advice to enroll in a reading course may have had different goals, attitudes, or

motivation than students in other groups (p. 117). In other words, individual student

characteristics upon entry into college may have contributed to student success.

College Student Characteristics and Behaviors

Student behaviors and characteristics such as personality factors have been explored and

attributed to the success of underprepared learners (Amey & Long, 1998; Ley & Young, 1998;

Ochroch & Dugan, 1986; Smith & Commander; Valadez, 1993). Ochroch and Dugan (1986)

concluded that personality factors such as self-esteem and internal locus of control were

correlated with success for high-risk students. Amey and Long (1998) compared successful and

College Readiness

unsuccessful underprepared students and concluded that differences in outcomes for the

students in the two groups were related to actions taken by the students and/or the institution

while the student was in attendance (p. 5). Because college places responsibility for success on

the student, self-regulating behavior may help indicate student readiness for college. Smith and

Commander (1999) observed student behavior in the classroom and concluded that many

students in regular classes, as well as in developmental education classes, failed to understand

college culture. They also found that students often lacked the tacit intelligence required for

success in college; this knowledge includes things such as attending class, being prepared, using

course materials, and collaborating with classmates. These authors recommend explicit teaching

of the practical skills needed for college.

College Culture

College readiness involves understanding student characteristics and skills within the

context of college. A students ability to navigate the culture has been shown to contribute to

success. For example, Napoli and Wortmans (1996) meta-analysis determined that student

academic and social integration was positively correlated with student success. Valadez (1993)

conducted ethnographic interviews to understand the role of cultural capital on the aspirations of

nontraditional students, finding strengths in what they contribute to the culture of college.

Method

The qualitative methods of this study followed an in-depth phenomenological interview

methodology (Cresswell, 2002; McMillan, 2000). Specifically, interview protocols as pioneered

by Perry (1968), conducted by Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger, and Tarule (1986) and, more

recently Light (2001), were followed. These studies share the quest for student voices in order to

College Readiness

deepen an understanding of adult development that might improve the practice of higher

education.

Participants

Eight participants volunteered from an upper division, undergraduate liberal arts program

of a small urban university located in the Pacific Northwest. The participants (a) were of junior

or senior status, (b) had earned an Associate of Arts degree from a community college, (c) were

older than 25, and (d) were first-generation college students.

Procedures

Partially structured, 30 to60 minute interviews were conducted with individual

participants to gather data about their backgrounds and experiences as college students. Protocol

questions were designed to encourage student perspectives of college readiness. To increase

reliability, each interview followed the same structured protocol, but clarifying questions were

sometimes asked. Immediately following each interview, the interviewer wrote a reflexive

journal entry (Erlandson, Harris, Skipper, & Allen, 1993), noting emerging themes and

highlights of each interview. Consistency and accuracy of interpretation was increased by

adhering to the structured protocol and by triangulation of data, which was achieved by

comparing researcher field notes with audiotapes of the interviews. Finally, participants were

invited to review and critique field notes and tape recordings. Credibility of data analysis was

strengthened with peer debriefing as the researchers worked together to discover and refine

themes.

While the interview protocol was carefully followed, qualitative design allows for

modification of the process as themes emerge. Rennie, Phillips, and Quartaro (1988) provide

validity for this constant comparative approach. After the first two participants were

College Readiness

interviewed, a question that asked about previous community college experience was added

because, during the first two interviews, participants focused on previous community college

experience.

Data Analysis. The interviews were transcribed verbatim for data analysis. All of the

transcripts were coded in their entirety. Records of the transcriptions and the coding process

constitute an audit trail of the data analysis procedure. Eventually, 10 themes were chosen to

code all of the data with a separate code for irrelevant information.

Results

Ten themes emerged and were organized into the following categories: (a) skills and abilities

perceived as important for college readiness, (b) background factors and life experiences that

contribute to college readiness, and (c) nontraditional student self-concept. The 11th code

irrelevant information was used for information not related to the research questions. The next

three sections describe codes and definitions that emerged in the qualitative analysis of

transcripts.

College Readiness: Skills and Abilities

This first category identifies participant ideas about skills and abilities that are important

for college readiness.

Code 1. Academic skills: Participants discussed essential academic skills that included (a)

reading, (b) writing, (c) math, (d) technology, (e) communication, and (f) study skills.

Code 2. Time management: Participants discussed the importance of time management

for college readiness

Code 3. Goal focus: Participants expressed the importance of having a goal and applying

oneself for college readiness.

College Readiness

10

Code 4. Self-advocacy: Participants shared advice or stories about being able to speak up

for ones needs and toseek help when necessary.

Background Factors

This second broad category identifies factors discussed by participants as influential to a

decision to enroll or prepare for college.

Code 5. Family factors: Participants shared family experiences or expectations about

college that influenced their decision or readiness for college.

Code 6. Career influences: Participants discussed work experience related to college

readiness or career motivations that influenced the decision to go to college

Code 7. Financial concerns: Participants shared experiences and issues about finances

and attending college.

Code 8. College preparation: Participants discussed previous high school and community

college educational experiences in relation to their readiness for university studies.

Nontraditional Student Self-concept

This third category identifies participants sense of identity as a college student and ideas

related to navigating the culture of college.

Code 9. Self-concept: Participants shared ideas about their identity as a college student

and/or changes to self-concept as a result of college experiences.

Code 10. College system: Participants shared a response that pertained to understanding

the college system, college standards, and the culture of college.

Code 11. Irrelevant information: Participants shared information that was irrelevant to

understanding college readiness.

College Readiness

11

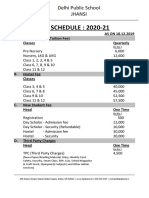

Table 1 shows data analysis according to the final 11 codes. The number of distinct instances a

response was mentioned for each code out of a total of 300 responses is indicated by responses..

The number of participants out of eight who included a response for each code is indicated by

participants..

College Readiness

12

Table 1

Codes

Category 1: College readiness skills and abilities

Code

Responses out of 300

Participants out of 8

1. Academic skills

18

2. Time management

19

3. Goal focus

24

4. Self-advocacy

16

Category 2: Background factors

Code

Responses out of 300

Participants out of 8

5. Family factors

40

6. Career influences

22

7. Financial concerns

22

8. College preparation

20

Category 3: Nontraditional student self-concept

Code

Responses out of 300

Participants out of 8

9. Self-concept

53

10. College system

39

Category 4: Irrelevant Information

Code

11. Irrelevant information

Responses out of 300

27

Participants out of 8

8

College Readiness

13

Qualitative Findings

College Readiness Skills and Abilities

In addition to recognized academic skills, participants of this study indicated that (a)

skills in time-management, (b) the ability to apply oneself and focus on a goal, and (c) skills for

advocating for oneself as a learner are essential for college readiness. Participants emphasized

these skills and abilities more than academic skills during the interviews. For example, the total

combined incidents where students mentioned any academic skills was 18; however, time

management alone generated 19 distinct responses, mentioned by all participants.

All participants discussed academic skills required for college readiness, recommending

that students preparing for college should strengthen skills in reading, writing, and math.

Reading and writing skills were discussed more often than other academic skills, with six

participants mentioning them. Four participants stressed reading as an area where they felt

underprepared academically, and this skill was often related to time management and high

university standards compared to community college and high school. Writing, on the other

hand, was often stressed as important, but only one participant mentioned feeling underprepared

in this area. Participants often reflected that students need strong writing skills for college, and

four participants claimed strong writing skills, using phrases such as: I am a writer, or a I am

a strong writer as a way to emphasize this as contributing to their readiness.

Time management is a skill that all of the participants noted as critical for college

readiness. Participants indicated the importance of this skill when discussing time needed for

studying outside class and course-load requirements while trying to manage priorities for work

and family. The theme of time management elicited a range of responses. Two participants

pointed to a lack of time and difficulty with time management as the biggest obstacles to doing

College Readiness

14

well in college, while other students related time management skills and multitasking abilities as

a strength contributing to readiness for college-level work. Six participants spoke of having

strong time management skills and related this strength to life experiences, especially work

related experiences, and to being older. Another attribute that students explicitly discussed as

essential for college readiness was goal focus. One participant said, When I think of what it

takes to be ready for college, I think its more of a mental mind setof having a goal. Like time

management, having a goal was related to student background factors, especially to career

influences and being older. Six participants explicitly compared a previous college experience

where they did not have a clear goal to their current experience of having a goal and the

importance of this goal for being ready for college.

Finally, the ability to advocate for oneself as a learner was articulated by five of the

participants as important for college readiness. While the other two attributes were explicitly

stated as essential for readiness, this theme of self-advocacy was more likely to be illustrated

through stories. Participants often attributed self-advocating skills with being older. One shared

how she felt more like a peer to faculty because of her age and that helped her approach the

instructor. For the students who participated in this study, the ability to self-advocate was critical

for an ability to navigate the college system. When participants shared stories of approaching

professors and seeking out advisors and counselors, they pointed to the importance of these

incidents for being successful in college and for the development of their own self-concept of

being a capable college student. For example, one spoke about his experience of approaching a

professor after he felt overwhelmed by the reading level on the first day: She just looked me

straight in the eye and said youre gonna do fine here because you approached me on the first

day.

College Readiness

15

Background Factors

Family factors often contributed to the participants readiness for college. Three

participants did share that family concerns had previously prevented them from continuing or

enrolling in college; however, three participants stressed that they were motivated to do better

than their parents and six participants shared positive stories of parental influence. Four

participants with children emphasized a desire to be a positive role model. One participant

shared: My daughter; shes my driving force. Shes the reason Im here right now, and she says

shes gonna go to school too. Generally, family was highlighted as important for all participants

with overlaps in themes of career influence and self-concept.

Work experiences and career motivations helped participants formulate a goal for

college. All eight participants pointed to the desire to improve career opportunities as a primary

motivation for enrolling in college. Two participants used the words dead-end job to describe

one of their main reasons for coming to college. Furthermore, five participants were motivated to

do better than their parents had done, noting that they saw their parents struggle in unsatisfying

careers. In addition to providing the motivation to attend college, four participants discussed

ways that skills and abilities learned at work transferred to college work. For instance, one

commented: I know that a lot of success in education has to deal with putting time and effort

into it, and Ive already put a lot of time into developing a career.

All participants gave testimony to the need for a college degree and seven discussed

financial concerns; however, the pattern of response for this was that a lack of finances should

not prevent someone from seeking a college degree. For example, one participant exclaimed:

People who dont have the money to pay for college themselves they shouldnt let that get in

the way. While this statement illustrates a common sentiment among the participants, there was

College Readiness

16

also a pattern of responses where participants reported not being aware of financial aid resources

when they began college, and some had delayed starting college for financial reasons or had paid

and later discovered financial aid was available. Another illustrated this theme when she said:

Its amazing; I mean I could have gone to college right after high school, but I really didnt

know that.

All eight participants discussed previous high school and community college experiences,

with seven reporting the feeling of being underprepared. For example, one participant noted:

Community college was like high school in a lot of ways. They didnt challenge you

intellectually. Your vocabulary could be a lot smaller. When I transferred over to the university, I

remember the first text I picked up and I was reading some of those words and I had this like

what does that mean. One participant did note that advanced placement classes in high school

were the only ones that helped prepare for workload requirements of university studies.

Nontraditional Student Self Concept:

Six participants emphasized that they were not ready for college when they were younger

or right after high school and that being older contributed to their readiness for college. While

two participants reported being older as an obstacle, for the most part it was perceived as a

benefit to college preparation. Participants illustrated that being older strengthened (a) selfconcept, (b) self advocacy, (c) goal focus, and (d) time-management skills. For example, I think

[having a goal] has to do with having some time not being in school and being in a job.

Specifically, one shared how being older helped students to give heartfelt responses during

class discussions, sharing how: Its actually things that youve lived through; you can apply

[what you know] and it makes learning a lot easier.

College Readiness

17

Five participants shared how they were surprised by their own success. Many of the

participants became quite animated, sharing their stories of being surprised and the continued

struggle to recognize their own work as good enough for college. One participant, when asked

what he would give as advice for nontraditional students, said: [They] need to know its

possible! This study suggests that nontraditional students may be more prepared than they think

for the demands of college and, moreover, that their life experiences may contribute to college

readiness.

Knowledge of the college system and having personal support were all mentioned as

important factors for success in college. All participants reported that they lacked sufficient

guidance and support from family or high school counselors to help prepare them for

understanding the college system. Awareness of financial aid availability was an area in which

participants felt particularly underprepared. One participant, even though she reported being

academically prepared in high school through advanced placement classes, said: I didnt know

how to get [to college] or what I needed to do, and [my parents] were not so helpful in that area

because they didnt know either, so its kind of been learn by trial and error. While six

participants spoke of having parental encouragement to go to college, four of these six also

emphasized that their parents had little to offer because of their own inexperience.

Discussion

One distinctive finding of this study is that first-generation students life experiences

contributed to the development of skills perceived as critical to success in college. In other

words, work experience and family motivations gave students the time management, goal focus

and self-advocacy skills that prepared them for the demands of college. While academic skills

are clearly important, time management, goal focus and self-advocacy emerged as more

College Readiness

18

important through stories, experiences, and reflections. These skills, it seems, are woven into or

emerge out of life experience more than do academic skills.

While the results of this study do not emphasize academic skills, one interesting finding

is that college reading was an area in which participants felt particularly underprepared. Reading

skills mentioned included vocabulary level and the amount of reading required. This discrepancy

of feeling underprepared for reading but not for writing could be because students come to

college expecting to be challenged by writing but not by reading, and then they are surprised by

their ability to write well. Also, writing and composition courses are offered at the college level

and many colleges offer the support of writing centers while reading courses are usually offered

only at the developmental level.

This study provides insight into the development of nonacademic skills that previous

researchers have recognized as important to college student success. For example, the emphasis

on goals in this study aligns with research conducted by Hoyt (1999) and Napoli and Wortman

(1996), which identified goals and commitments as fundamental to college student retention.

Likewise, time management may be an obvious factor for college readiness, but the fact that

participants of this study expressed it explicitly, emphatically and often underscores its

importance. More importantly, the theme that emerged from this study is that first-generation

students develop strengths that prepare them for college through their life experiences.

The theme of self-advocacy in this study is congruent with ideas about the relationship

between college student success and self-regulating behavior (Ley & Young, 1998). Ochroch and

Dugan (1986) suggest that successful students believe they have control over the outcome of

their lives. This belief is central to the ability to self-advocate. Furthermore, self-advocacy

emerged in this study as a particularly important skill for first-generation students who might not

College Readiness

19

have background knowledge of the college system to understand resources such as advising,

financial aid, and student-professor relationships.

Another distinctive implication of this study is that younger first-generation college

students might be particularly at risk for college readiness, given that life experience and being

older contributed to the skills of older first-generation students. This is of particular importance

because the responses for the theme of self-concept suggest that students whose parents did not

go to college may view themselves as less than adequate for college. This finding echoes K.P.

Crosss (1968) observation that we tend to view nontraditional students as less than adequate for

the demands of college. Indeed, the results of this research suggest that first-generation students

may internalize the view that they are inadequate for college.

Limitations of the Study

This study has limitations related to the design of the study and the potential for

generalization of findings due to sampling methods. An important limitation of this study is the

lack of multiple raters for data analysis. The first author collected and analyzed data and coded

transcript, and both authors interpreted the data for themes and conducted analysis of the

transcripts for each theme. No other researchers were trained in or performed data analysis, so no

inter-rater reliability was possible.

The sample used for this study also presents limitations for generalizability of the

research findings. The sample size of eight participants is a small one; furthermore, all of the

participants were students of the same program of study at the same small liberal arts college.

The study sample was limited to volunteers, which may affect the results of the study. Because

of this limited sample, it may have been more likely for students to articulate similar themes

related to college readiness than if the population had been broader. For example, this particular

College Readiness

20

population of students who are of junior or senior status in humanities studies may be stronger

writers than students who are in a different program or area of study. Also, the participants of

this study were well into their college studies, so their responses may not accurately reflect their

experiences and abilities when they began college. Perhaps some of the themes related to college

readiness reflect student development while in college.

Implications for Future Research

This study could be replicated with other samples of students for insights related to

college readiness. The patterns that emerged through these interviews suggest that there are

many factors that contribute to a students readiness for college-level work. A study like this one

could be carried out with comparative groups; for example, a study could be done to compare

nontraditional students with traditional college students (students whose parents went to college

and who are attending college right after high school). The results of this research also support

further research to understand college reading skills and college-level reading courses. Findings

from this study support further research to gain an understanding of college readiness and to add

to our understanding of nontraditional student populations in order to advance toward the goal of

helping all students be ready for college.

Implications for Practice

One of the implications of this study is that a definition of college readiness is more

complex than often acknowledged. A thorough understanding of college readiness must include

skills not measured by standardized tests. The results of this research indicate that skills in time

management, goal focus, and self-advocacy are all essential to college readiness. The researchers

recommend recognizing nonacademic skills for advising and placement decisions, especially for

first-generation students who might not be familiar with the college system. Acknowledgement

College Readiness

21

of these skills could help first-generation students recognize their strengths, especially if they are

required to take developmental coursework to prepare them for the academic demands of

college.

Another implication of this study is that younger college students may need to be taught

time-management, goal focus, and self-advocacy skills explicitly in first-year courses. In their

discussions of nontraditional students, Valadez (1993) and Hoyt (1999) both recommend

programs and support for first-generation college students to understand the college system and

college culture. The results of this study underscore their recommendation, especially for

younger first-generation students. This study also supports Lights (2001) claim that good

advising may be the single most underestimated characteristic of a successful college

experience (p. 81). Advising is likely to be even more important for first-generation college

students, especially younger ones.

The findings of this study support high standards at community colleges to prepare

students for university studies. This suggestion stems from the finding that community colleges

often did not adequately prepare students for the demands of a four-year college or university.

Perhaps community colleges could offer advising services and courses that target students who

are intending to transfer to four-year colleges. Furthermore, based on the results for academic

skills, the researchers recommend the development of and support for college-level reading skills

throughout the college experience.

While in the past some have viewed nontraditional students as inadequate for the

demands of college, this study highlighted nontraditional student strengths in connection to

college readiness. Results of this study indicate that life experiences, including work and family

College Readiness

22

experience, as well as being older contribute to the development of skills seen as essential to

college readiness.

Author notes:

Protocols and coding examples are available from the first author.

We are grateful to Professor Jose Rios who provided support and encouragement for this study.

College Readiness

23

References

Amey, J. A., & Long, P. A. (1998). Developmental coursework and early placement:

Success strategies for underprepared community college students. Community

College Journal, 22(3), 3-10.

Armstrong, W. B. (1999). The relationship between placement testing and curricular

content in the community college: Correspondence or misalignment? Journal

of Applied Research in the Community College, 7(1), 33-38.

Belenky, M. F., Clinchy, B. M., Goldberger, N. R., & Tarule, J. M. (1986). Womens ways

of knowing. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

Boylan, H. R., Bliss, L., & Bonham, B. S. (1997). The relationship between program

components and student success. Journal of Developmental Education, 20(2),

2-9.

Cresswell, J. W. (2002). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating

quantitative and qualitative research. Upper Saddle River, N J:

Merill/Prentice Hall.

Cross, K. P. (1968). The junior college student: A research description. Princeton, NJ

Educational Testing Service.

Day, P. R., & McCabe, R. H. (1997). Remedial education: A social and economic

imperative (Executive Issue Paper). American Association of Community Colleges.

Erlandson, D. A., Harris, E. L., Skipper, B. L., & Allen, S. (1993). Doing naturalistic inquiry: A

guide to methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Hennessy, J. H. (1990). At-risk community college students and a reading improvement

course: A longitudinal study. Journal of Reading, 34(2), 114-120.

College Readiness

Hoyt, J. E. (1999). Remedial education and student attrition. Community College Review,

27(2), 51-73.

King, B. W., Rasool, J. A., & Judge, J. J. (1994). The relationship between college

performance and basic skills assessment using SAT scores, the Nelson Denny

Reading test and Degrees of Reading Power. Research and Teaching in

Developmental Education, 11(1), 5-13.

Kraska, M. F., Nadelman, M. H., Maner, A. H., & McCormick, R. (1990). A comparative

analysis of developmental and nondevelopmental community college students.

Community/Junior College Quarterly of Research and Practice, 14, 13-20.

Lavin, D. E. (2000). Policy change and access to 2-and 4-year colleges: The case of the City

University of New York. The American Behavioral Scientist, 43, 1139-1158.

Ley, K., & Young, D. B. (1998). Self-regulation behaviors in underprepared

(developmental) and regular admission college students. Contemporary Educational

Psychology, 23, 42-62.

Light, R. J. (2001). Making the most of college: Students speak their minds. Cambridge,

MA. Harvard University Press.

McCabe, R. H. (2000). No one to waste: A report to public decision-makers and

community college leaders. Washington, DC: Community College Press.

McMillan, J. H. (2000). Educational research: Fundamentals for the consumer. New York:

Addison Wesley Longman.

Napoli, A. R., & Hiltner, G. J. (1993). An evaluation of developmental reading instruction.

Journal of Developmental Education, 17, 14-20.

Napoli, A. R., & Wortman, P. M. (1996). A meta-analysis of the impact of academic and

24

College Readiness

25

social integration on persistence of community college students. Journal of

Applied Research in the Community College, 4, 5-21.

Ntiri, D. W. (2001). Access to higher education for nontraditional students and minorities

in a technology focused society. Urban Education, 1, 129-144.

Ochroch, S. K., & Dugan, M. (1986). Personality factors for successful high-risk students.

Community/Junior College Quarterly of Research and Practice, 10, 95-100.

Perry, W. G. (1968). Forms of intellectual and ethical development in the college years.

New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Platt, G. M. (1986). Should colleges teach below-level-courses? Community College

Review, 14(2), 19-24.

Rennie, D. L., Phillips, J. R., & Quartaro, G. (1988). Grounded theory: A promising approach to

conceptualization in psychology? Canadian Psychology, 29(2), 139-150.

Smith, B. D., & Commander, N. E. (1997). Ideas in practice: Observing academic

behaviors for tacit intelligence. Journal of Developmental Education, 21(1), 3035.

U.S. Department of Education. (2000). Corporate involvement in education: Achieving

our national education priorities. The seven priorities of the U.S. Department of

Education. Washington, DC: (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED440307)

Valadez, J. (1993). Cultural capital and its impact on the aspirations of nontraditional

community college students. Community College Review, 21(3), 30-43.

College Readiness

26

You might also like

- College-Readiness FinalDocument101 pagesCollege-Readiness FinalJhoan Duldulao ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Analyzing Evidence of College Readiness: A Tri-Level Empirical & Conceptual FrameworkDocument66 pagesAnalyzing Evidence of College Readiness: A Tri-Level Empirical & Conceptual FrameworkJinky RegonayNo ratings yet

- Assessing Senior High Graduates Readiness for CollegeDocument33 pagesAssessing Senior High Graduates Readiness for CollegeMaria CrisalveNo ratings yet

- C S N H S: Agaytay Ity Cience Ational Igh ChoolDocument11 pagesC S N H S: Agaytay Ity Cience Ational Igh ChoolWea AguilarNo ratings yet

- Research Paper - Readiness of Senior High School Implementation of La Salle College - Final PDFDocument206 pagesResearch Paper - Readiness of Senior High School Implementation of La Salle College - Final PDFJhe Parcs88% (8)

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument9 pagesReview of Related LiteratureWea AguilarNo ratings yet

- Perceptions of Grade 10 Students in KVNHSDocument16 pagesPerceptions of Grade 10 Students in KVNHSjoey0% (1)

- Factors Affecting Grade 10 Students in CDocument57 pagesFactors Affecting Grade 10 Students in CMiyuki Nakata100% (1)

- Chapter 2 WoohDocument18 pagesChapter 2 WoohVivienne Louise BalbidoNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Study Habits On The AcademDocument13 pagesThe Impact of Study Habits On The AcademJames Fisc AndalesNo ratings yet

- Career Decision Making PDFDocument11 pagesCareer Decision Making PDFmb normilaNo ratings yet

- Factors that Influence Grade 11 Students in Choosing Their Senior High School StrandDocument36 pagesFactors that Influence Grade 11 Students in Choosing Their Senior High School StrandJiirem ArocenaNo ratings yet

- Practical ResearchDocument37 pagesPractical ResearchVinz Canoza100% (1)

- 3 IsDocument18 pages3 IsGlobe HacksNo ratings yet

- Factors That Influence Senior High Students' Career ChoicesDocument26 pagesFactors That Influence Senior High Students' Career ChoicesRosana CañonNo ratings yet

- Readiness of Senior High School Graduates For Business Education Programs in Selected Higher Education Institutions in IsabelaDocument32 pagesReadiness of Senior High School Graduates For Business Education Programs in Selected Higher Education Institutions in Isabelarhoda reynoNo ratings yet

- The Problem and The Review of Related LiteratureDocument14 pagesThe Problem and The Review of Related LiteratureCar Ro LineNo ratings yet

- Struggles Encountered by Grade 11 Students in ChoosingDocument9 pagesStruggles Encountered by Grade 11 Students in ChoosingAljoe Catchillar100% (1)

- Factors Affecting High School Students Career Preference (Group 4 - Jex)Document36 pagesFactors Affecting High School Students Career Preference (Group 4 - Jex)Mave Reyes100% (1)

- Factors Affecting Career Choices of Marketing StudentsDocument4 pagesFactors Affecting Career Choices of Marketing StudentsPrecious Vercaza Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Assessing Challenges Faced by The Grade 12 Humss Online Learning Students of Lagro High SchoolDocument3 pagesAssessing Challenges Faced by The Grade 12 Humss Online Learning Students of Lagro High Schooljose temothy ramos100% (1)

- Factors for Choosing ABM as Senior High StrandDocument3 pagesFactors for Choosing ABM as Senior High StrandMark Jason Santorce0% (1)

- Study Habit of The Grade 12 StudentsDocument46 pagesStudy Habit of The Grade 12 StudentsLORENA AMATIAGANo ratings yet

- Assessment For The Preparedness of Senio PDFDocument42 pagesAssessment For The Preparedness of Senio PDFlenard chavezNo ratings yet

- Edited Level of AwarenessDocument36 pagesEdited Level of AwarenessMaestro MertzNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Students' Career Choice: Asma Shahid Kazi, Abeeda AkhlaqDocument11 pagesFactors Affecting Students' Career Choice: Asma Shahid Kazi, Abeeda AkhlaqJeraldine DejanNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting The Study Habits of IT StudentsDocument18 pagesFactors Affecting The Study Habits of IT StudentsMahusay MagtagoNo ratings yet

- Factors That Affect COlLEge Course Selection of SeniorDocument28 pagesFactors That Affect COlLEge Course Selection of SeniorSha Margrete Cachuela100% (1)

- The Struggles of The Grade 11 Students On Their Choosen Strand 2Document13 pagesThe Struggles of The Grade 11 Students On Their Choosen Strand 2John Marvin Fabro OlaguerNo ratings yet

- The Association of The Self-Esteem of Senior High School Students Towards Their Efficacy On Academic PerformanceDocument56 pagesThe Association of The Self-Esteem of Senior High School Students Towards Their Efficacy On Academic PerformanceAllain Guanlao100% (1)

- Shs Strand Choice Vis-À-Vis Preparedness For Tertiary Education of Grade 12 Humss Students of Adzu-ShsDocument31 pagesShs Strand Choice Vis-À-Vis Preparedness For Tertiary Education of Grade 12 Humss Students of Adzu-ShsSTEPHEN EDWARD VILLANUEVA100% (1)

- CHAPTER 1 2 HumssDocument9 pagesCHAPTER 1 2 HumssRovelyn PimentelNo ratings yet

- Existence of Strand Caste SystemDocument5 pagesExistence of Strand Caste SystemLea Nexei EmilianoNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Grade 12 Students' Course ChoicesDocument12 pagesFactors Influencing Grade 12 Students' Course ChoicesRoland Dave SegoviaNo ratings yet

- Group 2 PR2Document34 pagesGroup 2 PR2Joana Marie DichosaNo ratings yet

- First City Providential CollegeDocument28 pagesFirst City Providential CollegeGiselle Grace ArandaNo ratings yet

- Career Preference Chapter 1 To 3Document12 pagesCareer Preference Chapter 1 To 3Lhaiela AmanollahNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Students Choice ForDocument46 pagesFactors Influencing Students Choice Forjudy ann naluz100% (1)

- Factors Influencing Career Choices Among High School Students in Zambales, PhilippinesDocument6 pagesFactors Influencing Career Choices Among High School Students in Zambales, PhilippinesLOPEZ, Maria Alessandra B.No ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Career Choices of Grade 12 StudentsDocument17 pagesFactors Influencing Career Choices of Grade 12 StudentsMary Peach EwicanNo ratings yet

- Peer Influence on Career Choice of Senior High StudentsDocument12 pagesPeer Influence on Career Choice of Senior High StudentsRc G Gopez100% (1)

- Perception of Senior High School Students Towards College ReadinessDocument57 pagesPerception of Senior High School Students Towards College ReadinessSarah Isabel Golo56% (9)

- Grade 12 Students' College ReadinessDocument18 pagesGrade 12 Students' College ReadinessLabo MacamosNo ratings yet

- Final OutputDocument36 pagesFinal OutputJayson PagalNo ratings yet

- An Analysis On The Choice of Grade 10 Students of MMHS Jess Ganda Ito Na Yung Ipapass Maagyos Na ToDocument14 pagesAn Analysis On The Choice of Grade 10 Students of MMHS Jess Ganda Ito Na Yung Ipapass Maagyos Na ToMDNo ratings yet

- Rogeline-ResearchDocument42 pagesRogeline-ResearchMelissa De LeonNo ratings yet

- Academic Stress On Academic Performance of StudentsDocument8 pagesAcademic Stress On Academic Performance of Studentsmae172001No ratings yet

- Group 4 (HUMSS 4) - Chapter 1-4 Compilation - RevisedDocument62 pagesGroup 4 (HUMSS 4) - Chapter 1-4 Compilation - RevisedNeil Marjunn TorresNo ratings yet

- A Study of Academic Achievement Among High School Students in Relation To Their Study HabitsDocument14 pagesA Study of Academic Achievement Among High School Students in Relation To Their Study HabitsImpact Journals100% (3)

- Chapter I-3Document10 pagesChapter I-3Wea AguilarNo ratings yet

- FACTORS AFFECTING THE DECISIONS OF GRADE 12 STUDENTS AT COLLEGE OF SUBIC MONTESSORI AstigDocument8 pagesFACTORS AFFECTING THE DECISIONS OF GRADE 12 STUDENTS AT COLLEGE OF SUBIC MONTESSORI AstigCj vacaro MendezNo ratings yet

- Checked TIME MANAGEMENT AND LEARNING STRATEGIES OF WORKING COLLEGE STUDENTSDocument98 pagesChecked TIME MANAGEMENT AND LEARNING STRATEGIES OF WORKING COLLEGE STUDENTSDiane Iris AlbertoNo ratings yet

- Choosing A College Course Latest UpdateDocument6 pagesChoosing A College Course Latest UpdateMARIA ERLINDA MATANo ratings yet

- PR Chapter1-2Document20 pagesPR Chapter1-2AnningggNo ratings yet

- A CORRELATIONAL STUDY OF PARENTING ATTITUDE PARENTAL STRESS AND ANXIETY IN MOTHERS OF CHILDREN IN GRADE 6thDocument98 pagesA CORRELATIONAL STUDY OF PARENTING ATTITUDE PARENTAL STRESS AND ANXIETY IN MOTHERS OF CHILDREN IN GRADE 6thAnupam Kalpana GuptaNo ratings yet

- Perceptions of Senior High School Academic Track Students of Jose Rizal University Towards Their Employability SkillsDocument17 pagesPerceptions of Senior High School Academic Track Students of Jose Rizal University Towards Their Employability Skillsbarrozoflorence100% (2)

- How Student and Parent Goal Orientations and ClassDocument21 pagesHow Student and Parent Goal Orientations and ClassMichad HollidayNo ratings yet

- Student Success Factors at Small Private CollegesDocument7 pagesStudent Success Factors at Small Private CollegesLisa WeathersNo ratings yet

- In Partial Fulfillment For The Inquiries, Nvestigation and MmersionDocument17 pagesIn Partial Fulfillment For The Inquiries, Nvestigation and Mmersiontaylor swiftyyy50% (2)

- 2022 9 4 10 QureshiDocument14 pages2022 9 4 10 QureshiSome445GuyNo ratings yet

- Reese ThompsonDocument4 pagesReese ThompsonAndrew DaumNo ratings yet

- The False Promise of 'Holistic' College AdmissionsDocument6 pagesThe False Promise of 'Holistic' College AdmissionsMyDocumateNo ratings yet

- Basicadaptations FulldocDocument3 pagesBasicadaptations FulldocMyDocumateNo ratings yet

- Advsopstem PDFDocument39 pagesAdvsopstem PDFjohnNo ratings yet

- Lifting The Veil On The Holistic Process at The University of California, BerkeleyDocument9 pagesLifting The Veil On The Holistic Process at The University of California, BerkeleyMyDocumateNo ratings yet

- Using TransitionsDocument2 pagesUsing TransitionsMyDocumateNo ratings yet

- What Does Columbia Look For?Document2 pagesWhat Does Columbia Look For?MyDocumateNo ratings yet

- Lifting The Veil On The Holistic Process at The University of California, BerkeleyDocument9 pagesLifting The Veil On The Holistic Process at The University of California, BerkeleyMyDocumateNo ratings yet

- Redefining College ReadinessDocument36 pagesRedefining College ReadinessMyDocumateNo ratings yet

- Twelve Common Errors Uwmadison Writingcenter Rev Sept2012 PDFDocument3 pagesTwelve Common Errors Uwmadison Writingcenter Rev Sept2012 PDFclevecNo ratings yet

- Fee Thresholds PDFDocument1 pageFee Thresholds PDFMyDocumateNo ratings yet

- SocratesDocument119 pagesSocratesLeezl Campoamor OlegarioNo ratings yet

- Silence and Omissions Essay PlanDocument2 pagesSilence and Omissions Essay PlanniamhNo ratings yet

- Hbet 4603 AssignmentsDocument13 pagesHbet 4603 Assignmentschristina lawieNo ratings yet

- JEE (Advanced) 2015 - A Detailed Analysis by Resonance Expert Team - Reso BlogDocument9 pagesJEE (Advanced) 2015 - A Detailed Analysis by Resonance Expert Team - Reso BlogGaurav YadavNo ratings yet

- Wax Paper Mono-PrintDocument3 pagesWax Paper Mono-Printapi-282926957No ratings yet

- Chief Petron: Dr. Bankim R. ThakarDocument2 pagesChief Petron: Dr. Bankim R. Thakargoswami vaishalNo ratings yet

- 08rr410307 Non Conventional Sources of EnergyDocument5 pages08rr410307 Non Conventional Sources of EnergyandhracollegesNo ratings yet

- BSC Applied Accounting OBU SpecificationsDocument8 pagesBSC Applied Accounting OBU SpecificationsArslanNo ratings yet

- Hemangioma Guide for DoctorsDocument29 pagesHemangioma Guide for DoctorshafiizhdpNo ratings yet

- Sri Ramachandra University Application-09Document5 pagesSri Ramachandra University Application-09Mohammed RaziNo ratings yet

- List of Cognitive Biases - WikipediaDocument1 pageList of Cognitive Biases - WikipediaKukuh Napaki MuttaqinNo ratings yet

- BUS 102 Fundamentals of Buiness II 2022Document4 pagesBUS 102 Fundamentals of Buiness II 2022Hafsa YusifNo ratings yet

- Module 9 - Wave Motion and SoundDocument27 pagesModule 9 - Wave Motion and SoundHanah ArzNo ratings yet

- Child and Adolescent DevelopmentDocument5 pagesChild and Adolescent Developmentandrew gauranaNo ratings yet

- Professional Interviewing Skills: Penni Foster, PHDDocument26 pagesProfessional Interviewing Skills: Penni Foster, PHDYanuar Rizal Putra Utama, S. PdNo ratings yet

- Summary 6Document5 pagesSummary 6api-640314870No ratings yet

- DLL W11 MilDocument4 pagesDLL W11 MilRICKELY BANTANo ratings yet

- Association of Dietary Fatty Acids With Coronary RiskDocument17 pagesAssociation of Dietary Fatty Acids With Coronary Riskubiktrash1492No ratings yet

- The Purpose of EducationDocument3 pagesThe Purpose of EducationbeatrixNo ratings yet

- R22 - IT - Python Programming Lab ManualDocument96 pagesR22 - IT - Python Programming Lab ManualJasmitha BompellyNo ratings yet

- What Is Exploration Reading Answers Afabb50cccDocument5 pagesWhat Is Exploration Reading Answers Afabb50cccmy computersNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Chapter 1Document10 pagesModule 1 Chapter 1MarckNo ratings yet

- Habits of The Household Audiobook PDFDocument38 pagesHabits of The Household Audiobook PDFHOPE TOOLS STORE100% (2)

- Bird personality testDocument6 pagesBird personality testMark Eugene IkalinaNo ratings yet

- Supranuclear Control Opf Eye MovementsDocument162 pagesSupranuclear Control Opf Eye Movementsknowledgeguruos179No ratings yet

- Secret Path Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesSecret Path Lesson Planapi-394112616100% (1)

- The Australian Curriculum: Science Overview for Years 1-2Document14 pagesThe Australian Curriculum: Science Overview for Years 1-2Josiel Nasc'mentoNo ratings yet

- Written Output For Title DefenseDocument6 pagesWritten Output For Title DefensebryanNo ratings yet

- 0list of School Bus Manufacturers PDFDocument4 pages0list of School Bus Manufacturers PDFMarlon AliagaNo ratings yet

- Fee Shedule 2020-21 Final DiosDocument2 pagesFee Shedule 2020-21 Final Diosapi-210356903No ratings yet

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo ratings yet

- The Silva Mind Method: for Getting Help from the Other SideFrom EverandThe Silva Mind Method: for Getting Help from the Other SideRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (51)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionFrom EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2475)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (402)

- The One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsFrom EverandThe One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (708)

- Can't Hurt Me by David Goggins - Book Summary: Master Your Mind and Defy the OddsFrom EverandCan't Hurt Me by David Goggins - Book Summary: Master Your Mind and Defy the OddsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (382)

- Summary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesFrom EverandSummary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1631)

- The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentFrom EverandThe Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4120)

- Becoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonFrom EverandBecoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1476)

- Summary of The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental IllnessFrom EverandSummary of The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental IllnessNo ratings yet

- The 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageFrom EverandThe 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (7)

- The Science of Self Discipline: How Daily Self-Discipline, Everyday Habits and an Optimised Belief System will Help You Beat Procrastination + Why Discipline Equals True FreedomFrom EverandThe Science of Self Discipline: How Daily Self-Discipline, Everyday Habits and an Optimised Belief System will Help You Beat Procrastination + Why Discipline Equals True FreedomRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (864)

- The Art of Personal Empowerment: Transforming Your LifeFrom EverandThe Art of Personal Empowerment: Transforming Your LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (51)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (327)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The 16 Undeniable Laws of Communication: Apply Them and Make the Most of Your MessageFrom EverandThe 16 Undeniable Laws of Communication: Apply Them and Make the Most of Your MessageRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (72)

- The Compound Effect by Darren Hardy - Book Summary: Jumpstart Your Income, Your Life, Your SuccessFrom EverandThe Compound Effect by Darren Hardy - Book Summary: Jumpstart Your Income, Your Life, Your SuccessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (456)

- Summary of 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to ChaosFrom EverandSummary of 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to ChaosRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (294)

- The Motive: Why So Many Leaders Abdicate Their Most Important ResponsibilitiesFrom EverandThe Motive: Why So Many Leaders Abdicate Their Most Important ResponsibilitiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (219)

- Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeFrom EverandIndistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Uptime: A Practical Guide to Personal Productivity and WellbeingFrom EverandUptime: A Practical Guide to Personal Productivity and WellbeingNo ratings yet

- Own Your Past Change Your Future: A Not-So-Complicated Approach to Relationships, Mental Health & WellnessFrom EverandOwn Your Past Change Your Future: A Not-So-Complicated Approach to Relationships, Mental Health & WellnessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (85)

- Quantum Success: 7 Essential Laws for a Thriving, Joyful, and Prosperous Relationship with Work and MoneyFrom EverandQuantum Success: 7 Essential Laws for a Thriving, Joyful, and Prosperous Relationship with Work and MoneyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (38)

- Midnight Meditations: Calm Your Thoughts, Still Your Body, and Return to SleepFrom EverandMidnight Meditations: Calm Your Thoughts, Still Your Body, and Return to SleepRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)