Professional Documents

Culture Documents

NIH Public Access

Uploaded by

Fajar Rudy QimindraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

NIH Public Access

Uploaded by

Fajar Rudy QimindraCopyright:

Available Formats

NIH Public Access

Author Manuscript

Neuropsychiatry (London). Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Published in final edited form as:

Neuropsychiatry (London). 2011 October 1; 1(5): 431440. doi:10.2217/npy.11.57.

A perspective on the proposal for neurocognitive disorder

criteria in DSM-5 as applied to HIV-associated neurocognitive

disorders

Karl Goodkin, Francisco Fernandez1, Marshall Forstein2, Eric N Miller3, James T Becker4,

Antoine Douaihy4, Luis Cubano5, Flavia H Santos6, Nelson Silva Filho7, Jorge Zirulnik8,

and Dinesh Singh9

1Department of Psychiatry & Neurosciences, Institute for Research in Psychiatry, University of

South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA

2Department

of Psychiatry, Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA

3UCLA

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Semel Institute for Neuroscience, Department of Psychology, University of California at

Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

4Department

of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

5Department

of Microbiology & Immunology, Research & Graduate Studies, School of Medicine,

Universidad Central del Caribe, Bayamn, Puerto Rico, USA

6Laboratory

of Neuropsychology, Department of Experimental Psychology, University of the State

of So Paulo, Brazil

7Department

8Infectious

of Clinical Psychology, University of the State of So Paulo, Brazil

Diseases & HIV/AIDS Unit, Hospital Juan A Fernandez, Buenos Aires, Argentina

9Department

of Psychiatry, University of Kwa-Zulu Natal, South African Research Council,

Durban, South Africa

SUMMARY

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders remain common in the current era of effective

antiretroviral therapy. However, the severity at presentation of these disorders has been reduced,

and the typical manifestations have changed. A revision of the American Academy of Neurology

(AAN) criteria has been made on this basis, and a revision of the analogous criteria by the

American Psychiatric Association will be forthcoming in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders (DSM)-5. This article compares the relevant sets of diagnostic criteria that will

be employed. It is concluded that a greater degree of integration of the revised, HIV-specific AAN

criteria for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders with the criteria proposed for the DSM-5

would prove advantageous for research, clinical, educational and administrative purposes.

The current proposal for the criteria to be used for neurocognitive disorders in the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-5 has been published in a

2011 Karl Goodkin

Author for correspondence: AIDS Healthcare Foundation, 6255 W Sunset Blvd, 21st Floor, Los Angeles, CA 90028, USA; Tel.: +1

323 860 5250; Fax: +1 323 962 8513; karl.goodkin@aidshealth.org.

Disclosure

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Institute of

Mental Health or the National Institute on Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Goodkin et al.

Page 2

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

draft form [1]. This proposal is intended to include the area of HIV-associated

neurocognitive disorders (HAND). However, the proposal is based upon an update of the

more general criteria proposed for Delirium, Dementia, and Amnestic, and Other Cognitive

Disorders published in the DSM-IV [2,3]. The DSM-IV contained no specific criteria for

HAND, and the current proposal for these disorders in the DSM-5 would have the same

result. Yet such an outcome could lead to a continued lack of utilization by psychiatrists of

diagnostic criteria with widely acknowledged specificity for HAND and a lack of integration

with the current research on HAND. HAND is not well represented by the criteria developed

for Alzheimer's disease (AD), which largely constitute the basis upon which the DSM-IV

criteria were defined in the aforementioned cognitive disorders subsection. This remains the

case when adding the consideration of the impact of minor cognitive impairment, as

defined for the general population. This article will systematically present the evidence

addressing how the lack of integration of the DSM criteria with the Frascati conferencebased revision of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) criteria for HAND over time

detracts from the future utility of the diagnoses of the neurocognitive disorders associated

with HIV infection in the DSM-5.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

If the currently proposed draft criteria for neurocognitive disorders in the DSM-5 are

successfully promulgated, not only will the criteria that will be applied to HAND be

improperly depicted in an overly generalized fashion, but it will also remain the case that

there will be no specific criteria for HAND at all. First, it should be stated that HAND is

significantly different from AD, as HAND is based upon a neuroinfectious process with a

predilection for the basal ganglia, periventricular white matter and the hippocampus. HAND

may occur at a much younger age and is more likely to be reversible. At least initially,

HAND is best represented as a subcortical dementia as opposed to AD, which is best

characterized as a cortical dementia. While it can be argued that this differentiation is not

definitive, it aids heuristically in depicting how these different types of neurocognitive

disorder present. Moreover, the lack of inclusion of any explicitly defined criteria for HAND

was not justified in the DSM-IV, just as it remains unjustified today for the DSM-5. When

the DSM-IV was published in 1994, specific criteria for HAND had already been published

by the AAN for 3 years [4]. Those criteria had explicitly defined the disorders of HIVassociated dementia (HAD) and HIV-associated minor cognitive-motor disorder

(MCMD). Yet, the DSM-IV criteria ultimately made no reference to any specific criteria for

HAND. While a relevant diagnosis was nominally included in the DSM-IV (as a subtype of

dementia due to a general medical condition [294.1]), there were no specific criteria

assigned to it. Furthermore, there was no analog for the less severe disorder of HIVassociated MCMD in the final, approved version of the DSM-IV [2,3]. Although a research

diagnosis analogous to MCMD was designated and listed in research appendix B as mild

neurocognitive disorder (MND) in the DSM-IV [2,3], the only approved diagnostic term for

this disorder was cognitive disorder not otherwise specified (294.9).

The current proposal for neurocognitive disorders in the DSM-5 makes no reference to the

criteria that have been designated for HAND in neurology. However, 4 years ago, the AAN

criteria were revised and published by an expert, international consensus panel. This

revision was based upon the need to redefine the criteria for HAND that were originally

promulgated in 1991 due to changes in the manifestations of HAND over the subsequent 16

years, particularly following the introduction of effective antiretroviral therapy (ART). It has

been reported that: the spectrum of severity of clinical symptoms has been dampened in the

era of effective ART [5]; there are neuropathological correlates for this reduced level of

clinical severity (although the prevalence remains high) [6]; and patients with HAD have a

longer survival time in the current era [7]. Thus, the DSM-IV criteria identifying HAND

only at the level of a dementia had become progressively less sensitive over time. However,

the diagnostic criteria currently proposed for the neurocognitive disorders in DSM-5 still

Neuropsychiatry (London). Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 01.

Goodkin et al.

Page 3

make no reference to the revised criteria for HAND adopted in neurology. Thus, the same

lack of cross-referencing of these disorders across related fields is likely to occur again.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

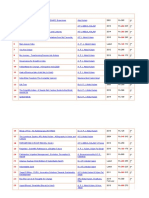

Currently, the DSM-5 work group is recommending that HAD be subsumed under a new

disorder to be termed major neurocognitive disorder (Table 1) [1]. For the purposes of

discussion, please refer to the revised, HIV-specific AAN criteria for HAD that follow:

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

There must be a marked, acquired impairment in neurocognitive performance,

involving at least two domains (or areas). In addition, the presence of neurocognitive

impairment must be ascertained by neuropsychological (NP) testing with at least two

domains demonstrating scores at 2 standard deviations (SDs) or greater below the

demographically corrected means. Typically, impairment is observed over multiple

domains, especially in the areas of information processing speed, learning of new

information, verbal memory and attention/concentration. It is noted that for resourcelimited settings where NP testing is not available, a standard neuropsychiatric

evaluation and simple bedside mental status examination testing may be substituted for

standardized NP testing. Nevertheless, this should be done with standardized

assessments of mental status. While the Mini-Mental State Examination with an index

for the presence of neurocognitive impairment taken as a score of less than 26 [8] was

referenced in the revised AAN criteria [9], this screening device should not be used due

to its lack of sensitivity for the predominantly subcortical neurocognitive processes

comprising HAND. Other standardized mental status examinations that might be used

include the HIV Dementia Scale [10] and the International HIV Dementia Scale [11]. It

is preferred that the domains selected for screening do not include the language domain,

which is typically preserved in HAND until the late stage of disease. However, a timed

test of language performance may be employed with validity.

The neurocognitive impairment observed must be associated with marked

interference in functional status of activities of daily living. It is preferred but not

required that functional status be confirmed by standardized measures with established

norms. However, standardized measures are required for documentation of impaired

neuro cognitive performance. Ideally, both self-report and objective functional status

measures should be employed, as patients frequently minimize the report of the deficits

consistent with a frontostriatal process like HAND. Of note, examples of useful selfreport functional status measures are the Sickness Impact Profile [12], the Cognitive

Difficulties Scale [13] and the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS)-HIV Cognitive

Functional Status Subscale [14,15]. Examples of objective functional status measures

are the Direct Assessment of Functional Status [16] and the University of California at

San Diego (UCSD) Performance-Based Skills Assessment [17].

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

The neurocognitive impairment should not support the diagnosis of delirium. That is,

disturbance of consciousness and a short period of evolution of the observed

impairment should not be prominent features [2,3]. If delirium is present, then the

criteria for dementia must have been met previously.

There should be no evidence of another, pre-existing cause for the dementia. There

are many potentially confounding conditions to be considered that are associated with

or are specific to the immunodeficiency associated with HIV that would not be part of a

standard work-up for dementia in an immunocompetent patient. These confounding

illnesses include neurological conditions dating back to the beginning of the epidemic

(e.g., CNS toxoplasmosis, cryptococcal meningitis, cytomegalovirus encephalopathy,

primary CNS lymphoma, neurosyphilis and tuberculous meningitis). In addition, several

conditions of recently increasing neurological awareness and concern in the HIV

infected should be assessed (e.g., cerebrovascular disease, CNS hepatitis C virus

infection and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome manifesting with CNS

Neuropsychiatry (London). Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 01.

Goodkin et al.

Page 4

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

symptoms). Moreover, psychiatric confounding conditions should be excluded (e.g.,

major depressive disorder and bipolar affective disorder [and associated mania]), as

should neuropsychiatric prescribed medication toxicities (e.g., those associated with

IFN- and efavirenz) and intoxication, withdrawal and long-term sequelae associated

with psychoactive substance use (e.g., methamphetamine, cocaine and alcohol).

The aforementioned revised criteria were developed at the Frascati conference by an

international working group charged by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and

the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) of the USA to

critically review the adequacy and utility of the prior AAN criteria. Those criteria differ

significantly from the generalized neurocognitive disorder criteria that have been suggested

by the DSM-5 Neurocognitive Disorders Work Group:

First and foremost, it must be pointed out that the DSM-5 criteria are not specific in

terms of etiology. In the case of HAND, the pathogen has been identified and should be

specified to be HIV.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Second, the proposed DSM-5 criteria indicate that the diagnosis must be based upon

report by the patient or a knowledgeable informant or by observation by a clinician,

together with deficits on standardized NP testing. However, in the revised AAN criteria

standardized NP testing is fully relied upon, and it is not required that a report of the

patient, a report of a knowledgeable informant or a confirmatory observation by a

clinician be documented.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Third, the proposed DSM-5 neurocognitive domains to be sampled differ from that

set forth in the revised AAN criteria. The DSM-5 supports the idea of six domains:

complex attention (sustained attention, divided attention, selective attention and

information processing speed); executive ability (planning, decision-making, working

memory, responding to feedback/error correction, overriding habits and mental

flexibility); learning and memory (immediate memory and recent memory [including

free recall, cued recall and recognition memory]); language (expressive language

[including naming, fluency, grammar and syntax] and receptive language);

visuoconstructionalperceptual ability (construction and visual perception); and social

cognition (recognition of emotions, theory of mind and behavioral regulation). The

revised AAN criteria denote seven domains: verbal/language, attention/working

memory, abstraction/executive functioning, memory (learning and recall), speed of

information processing, sensoryperceptual, and motor skills. The primary differences

are that the DSM-5 criteria include a domain of social cognition not included in the

revised AAN criteria, while the revised AAN criteria denote information processing

speed and motor skills as separate domains not included by the DSM-5 criteria. Little to

no data exist on the importance of social and emotional cognition in the diagnosis of

HAND, and it is likely that the inclusion of this domain would bias against the

likelihood of reaching a HAND diagnosis. The revised AAN criteria are based upon the

research on HAND demonstrating that information processing speed is considered to be

the hallmark of deficits observed in early HAND [18]. In addition, the motor domain is

well known to be affected by HIV infection of the brain, manifesting as secondary

Parkinsonism [19] related to basal ganglia infection occurring as an early-recognized

event [20] and associated with neurocognitive changes [21]. It is unclear how the

inclusion of the virtually unstudied domain of social cognition by the DSM-5 could be

expected to offset its omissions of the frequently impaired domains of information

processing speed and motor function in HAND.

Fourth, another important difference between these two criteria sets is that the revised

AAN criteria set requires that at least two NP domains be impaired, whereas the DSM-5

Neurocognitive Disorder Work Group criteria require only one NP domain to be

Neuropsychiatry (London). Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 01.

Goodkin et al.

Page 5

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

impaired. The issue with the use of a single domain-based impairment definition is that

it is not sufficient to denote the global deterioration of neurocognitive performance

required by definition with the use of the term dementia and analogously by

major neurocognitive disorder as well. In fact, it is not uncommon to find that isolated

impairment in the memory domain may particularly occur without any impairment in

other domains, and such a condition is better defined as a different syndrome.

Fifth, the quantified level of deficit required in NP performance differs between the

two criteria sets as well. The revised AAN criteria for HAD indicate that impairment

must be ascertained by NP testing with at least two domains being 2 SDs or greater

below demographically corrected means. Alternatively, the patient could score greater

than 2.5 SDs below norms (an operational definition for moderate to severe

impairment) on one domain and greater than 1 SD below norms on another. However,

the DSM-5 Work Group criteria do not impose a quantified impairment definition and

only specify that typically the deficits will be >2 SDs below the mean (or below the

2.5th percentile) of an appropriate reference population. In order to generally

standardize diagnoses of HAND, the use of a quantified NP impairment definition

would improve reliability and validity, and the revised AAN criteria present a yet more

differentiated approach to the level of HAND with respect to MND versus HAD by the

application of its differential, quantitative NP cutoffs for these diagnoses.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Sixth, the DSM-5 Neurocognitive Disorder Work Group criteria require that the

neuro-cognitive deficits be associated specifically with deficits in functional status in

activities of daily living involving independence. However, the revised AAN criteria

simply require that the neurocognitive impairment produces marked interference with

any activities of daily living (e.g., work, home life or social activities regardless of

whether they interfere with independence). The requirement of deficits in independence

would likely skew the frequency of these diagnoses toward a more severe level than

would otherwise be the case when general activities of daily living are assessed. The

rationale for prioritizing independence in HAND diagnoses or for neuro-cognitive

disorder diagnoses more generally is unclear. Another advantage of the revised AAN

criteria is that they recommend (but not require) that standardized functional status

instruments be used. Of note, the instruments chosen should have norms that are

appropriate to the patient population being examined (i.e., for that patient's culture and a

comparable sociodemographic group).

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

A seventh and final issue with the criteria promoting major neurocognitive disorder

(as defined by the DSM-5) versus those promoting HAD (as defined by the revised

AAN criteria) are the exclusionary criteria that must be met. The DSM-5 Work Group

states that the neurocognitive deficits not be wholly or primarily attributable to another

axis I psychiatric disorder (e.g., major depressive disorder or schizophrenia). By

contrast, the revised AAN criteria state that there should be no evidence of another, preexisting cause for the dementia (e.g., other CNS infection, CNS neoplasm,

cerebrovascular disease or pre-existing neurologic disease). Of note, the revised AAN

criteria for HAD include ruling out relevant psychiatric disorders as a pre-existing cause

as well (e.g., substance dependence compatible with CNS disorder and major depressive

disorder), whereas the DSM-5 Neurocognitive Disorder Work Group criteria do not

analogously specify exclusion of neurological or general medical conditions of any

kind. It would seem that the latter approach should be modified at this time in the

development of research on CNS diseases when specific etiologies are generally

becoming much more commonly focused upon and are of manifest relevance to the

definition of HAD.

Considering the less severe neurocognitive disorder subsumed by the term HAND, there

are also currently no HIV-specific criteria denoted in the DSM-IV [2,3] for either HIVNeuropsychiatry (London). Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 01.

Goodkin et al.

Page 6

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

associated MND as defined by Antinori et al. [9], or for the previously defined AAN

diagnosis of HIV-associated minor cognitive-motor disorder [4]. This diagnosis as alluded

to previously falls under the DSM-IV generic diagnosis of cognitive disorder not

otherwise specified (294.9). However, we have previously noted that the MND diagnosis

could be mapped to the non-HIV-specific research diagnosis of the same name contained in

appendix B of DSM-IV. In that research appendix, the term MND is not related to etiology

and is defined as requiring two or more of the following: memory impairment, executive

function deficits, attention and information processing speed deficits, perceptualmotor

impairment and language impairment. Of note, the functional status criterion of MND in

DSM-IV appendix B was that the neurocognitive deficits should cause marked distress or

impairment in social, occupational and other important areas..., which would seem to be

inappropriate for this mild disorder.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

The current criteria proposed for this neurocognitive disorder in the DSM-5 have changed

the DSM-IV research diagnosis nomenclature of mild neurocognitive disorder to minor

neuro cognitive disorder. As such, this is the opposite of the analogous change in

nomenclature between the prior [4] and current [9] sets of AAN neurocognitive disorder

criteria. In this case, the prior term was HIV-associated minor cognitive-motor disorder

and the current term is HIV-associated mild neurocognitive disorder. Given the DSM-5

Neurocognitive Disorder Work Group's statement about the term dementia having

acquired pejorative and stigmatizing connotations, it would seem that the work group might

be similarly concerned about the connotations for the public of the term minor

neurocognitive disorder. This term could be anticipated to be perceived as diminishing the

importance of the functional consequences of this disorder. In fact, the patients so diagnosed

may perceive this disorder as anything but minor in terms of its impact in their own lives.

Hence, it is unclear why the switch from mild neurocognitive disorder to minor neurocognitive disorder would have been made, and the change seems to be inconsistent with

that made by deleting the term dementia in favor of major neurocognitive disorder.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Beyond diagnostic labels, the comparison of the less severe neurocognitive disorder criteria

sets themselves are similar to those between major neurocognitive disorder and HAD

with two exceptions. One is that the NP deficits are now defined as mild on NP testing by

the DSM-5 Neurocognitive Disorders Work Group (i.e., typically 12 SDs below the mean

[or in the 2.516th percentile] of an appropriate reference population). The other is that the

deficits must not be sufficient to interfere with functional status related to the maintenance

of independence, although greater effort and compensatory strategies might be required to

maintain independence. In terms of the comparison between the mild and more severe

disorders as defined by the revised AAN criteria, the criteria for MND are similar to those

defined for HAD, with the exceptions that the acquired impairment in neurocognitive

performance involves performance on standardized NP tests of at least 1 SD below the mean

for appropriate norms (with the same domains defined as those for HAD), and that the

neurocognitive impairment is associated with at least mild interference in functional status

of activities of daily functioning. It is also suggested that performance-based, standardized

functional status tests should also be administered, with patient scores >1 SD below an

appropriate normative mean required for the diagnosis. In addition and of specific relevance

to MND, language function is typically preserved until late-stage HIV CNS disease. Hence,

the proposed DSM-5 Work Group criteria including language as a domain for MND are not

as well supported as those proposed for the revised AAN criteria, in which the comparable

domain is defined as verbal/language. The latter domain has a much broader purview by

including all verbal functions rather than language functioning alone. Thus, regardless of the

prior considerations of the differences between criteria sets on major neurocognitive

disorder and HAD, it may be concluded that the proposed DSM-5 Neurocognitive

Neuropsychiatry (London). Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 01.

Goodkin et al.

Page 7

Disorder Work Group nomenclature and criteria for minor neurocognitive disorder would

require additional revisions.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Finally, consider the mildest neurocognitive condition subsumed by the term HAND,

HIV-associated asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI), which has been adopted

with the revision of the AAN criteria [9]. There is no analogous diagnostic term in the DSMIV in either the approved or research criteria sets, nor in the proposed criteria for the DSM-5

currently promoted by the Neurocognitive Disorders Work Group. The revised AAN criteria

define ANI as presented earlier for MND with the exception that the acquired

neurocognitive impairment does not interfere with functional status in activities of daily

living. It is important to note that this diagnostic entity is more properly classified as a

condition rather than a disorder, as its presence is not intended to represent an illness,

which would mandate treatment in order to re-establish normal functioning. Rather, this

term represents a potential predecessor of an illness, which does not currently mandate

treatment because functional status in activities of daily living remains normal. It might be

suggested that subclinical neurocognitive impairment should be preferred to ANI, as these

patients may experience and complain of neurocognitive symptoms but still not qualify by

the results of their functional status assessment for the diagnosis of MND.

Conclusion

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

A significant set of disjunctions has been identified between the proposed DSM-5

Neurocognitive Disorder Work Group's revision of the DSM-IV criteria as applied to

HAND [2,3] and the HIV-specific criteria set forth by the Frascati conference-based revision

of the prior AAN criteria for HAND [4,9]. Of general importance, the combined prevalence

of the conditions subsumed by HAND renders HAND as the most prevalent neuro-AIDS

condition today. Within this spectrum, HAD has received more-than-adequate research

attention to demonstrate that it is sufficiently unique to warrant being described with its own

specific diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5. It is manifest that the neurocognitive disorder

diagnoses as applied to HAND should be defined as requiring demonstration of positive

HIV serostatus. Regarding other general changes, the attempt to define criteria less directly

related to those for AD represents progress in the proposed DSM-5 criteria for the

neurocognitive disorders. In addition, the indicated change to create a single categorical

heading neurocognitive disorder (differentiated as major vs minor) might be

considered to be an advantage for the proposed DSM-5 criteria over the revised AAN

criteria. Moreover, this would be true for the elimination of the term dementia in favor of

major neurocognitive disorder. However, it seems that the reverse applies regarding the

change from mild neurocognitive disorder in the DSM-IV (and in the currently revised

AAN criteria) to minor neurocognitive disorder proposed for the DSM-5. It must also be

argued that at least two domains should be required to be impaired to imply the global

deterioration of functioning implied by the term neurocognitive disorder (whether major or

minor), as is required by the revised AAN criteria for HAD, MND and ANI. Overall, the

advantages for the revised AAN criteria set are that neurocognitive deficits are explicitly

quantified and functional status deficits are not limited to the specific aspect of

independence. By contrast, any type of functional status compromise that is referable to

HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment is consistent with the diagnosis of HAND.

Finally, the exclusion criteria required for these diagnoses should span both neurologic and

psychiatric disorders and should include CNS illnesses specific to the setting of

immunodeficiency caused by HIV infection, as noted by both the original AAN criteria and

the current Frascati conference-based criteria. The integration of the foregoing

considerations into the neurocognitive disorder criteria proposed for the DSM-5 would bring

the psychiatric diagnostic criteria to be applied to HAND to the point of addressing the

Neuropsychiatry (London). Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 01.

Goodkin et al.

Page 8

established specificity of neurocognitive disorders (major and minor) in HIV infection and

to integrating published research results on the entities comprising HAND.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

The clinical implications of these changes are noteworthy, as the specification of the

diagnoses subsumed by HAND in the DSM-5 would allow psychiatrists to internationally

utilize these diagnoses more systematically for psychiatric clinical purposes, whether or not

local resources allowed for standardized NP testing. Such changes would also contribute to a

greater integration of HIV psychiatry within mainstream psychiatry. In addition, they would

allow the more ready coordination of clinical care with neurologists using the revised

criteria originated by the AAN. Moreover, use of such a coordinated diagnostic system for

HAND would allow improved communication and care coordination with the primary care

provider (most typically an infectious disease physician specializing in HIV medicine). It

should also be pointed out that HAND represents only one type of neurocognitive disorder

of a group that might be similarly considered for their own specific diagnostic criteria in the

DSM-5, most notably AD [2225]. While criteria are suggested for AD within the proposal

of the DSM-5 Neurocognitive Disorders Work Group, those criteria are presented as a

subtype of major and minor neurocognitive disorder and as an example of how specific

etiologies would be coded. No criteria for any other subtype of neurocognitive disorder are

offered.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Finally, and most importantly, the delineation of HIV-specific neurocognitive disorder

diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5 would allow reimbursement of psychiatrists for clinical

interventions aimed at the treatment of both MND and major neurocognitive disorder

associated with HIV infection. These interventions include the potential use of CNSpenetrating ART, psychostimulants and other therapies aimed at neurotransmitter

manipulation, CNS anti-inflammatory agents, antineurodegenerative agents, neurotrophic

agents, nutritional manipulation and a spectrum of cognitive rehabilitative techniques.

Future perspective

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Dementia and other cognitive disorders, due to HIV infection, were classified solely at a

nominal level by prior versions of the DSM. Therein, they have been referred to as a

dementia or a cognitive disorder due to a general medical condition. This broad rubric has

significantly limited the utility of these diagnoses to psychiatrists for both diagnostic and

treatment purposes. However, specific criteria for the HIV-associated subset of these

disorders have now been in use by neurologists for 20 years. To account for changes that

more recent research has documented in these entities since the introduction in 1996 of

highly active ART (now referred to as combination ART or simply as effective ART),

those criteria were revised based upon an international consensus conference 4 years ago.

An opportunity for integration with this diagnostic revision now presents itself with the

advent of the DSM-5.

Acknowledgments

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This work has been supported by NIH grants R01 MH58532 and R21 MH75658 to K Goodkin. The authors have

no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or

financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

Neuropsychiatry (London). Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 01.

Goodkin et al.

Page 9

of interest

of considerable interest

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

1. Jeste, D.; Blacker, D.; Blazer, D., et al. Neurocognitive Disorders. A Proposal from the DSM-5

Neurocognitive Disorders Work Group. American Psychiatric Association; VA, USA: 2010. p.

1-17. [Sets forth the proposed neurocognitive disorder criteria (subsuming HIV-associated

neurocognitive disorders [HAND]) to be incorporated into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

of Mental Disorders (DSM)-5.]

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th

Edition. American Psychiatric Association; VA, USA: 1994.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th

Edition. American Psychiatric Association; VA, USA: 2000. Text Revision

4. American Academy of Neurology. Nomenclature and research case definitions for neurological

manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1) infection. Neurology. 1991;

41:778785. [PubMed: 2046917] [Historical paper that first set forth HAND criteria.]

5. Brew BJ. Evidence for a change in AIDS dementia complex in the era of highly active antiretroviral

therapy and the possibility of new forms of AIDS dementia complex. AIDS. 2004; 18(Suppl.

1):S75S78. [PubMed: 15075501]

6. Neuenburg JK, Brodt HR, Herndier BG, et al. HIV-related neuropathology, 1985 to 1999: rising

prevalence of HIV encephalopathy in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Acquir.

Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 2002; 31:171177. [Demonstrates that

neuropathological data confirmed the reduced level of clinical severity of HAND noted in the era

of effective antiretroviral therapy (ART).]

7. Dore GJ, McDonald A, Li Y, Kaldor JM, Brew BJ. Marked improvement in survival following

AIDS dementia complex in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2003; 17(10):

15391545. [PubMed: 12824792] [Epidemiological paper that indicates a marked improvement

in survival time for patients with HIV-associated dementia in the era of effective ART,

suggesting that the prevalence of HIV-associated dementia had actually increased.]

8. Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Population-based norms for the mini-mental state

examination by age and educational level. JAMA. 1993; 269:23862391. [PubMed: 8479064]

9. Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated

neurocognitive disorders (HAND). Neurology. 2007; 69:17891799. [PubMed: 17914061] [Set

forth the revision of the historical HAND criteria [4] for the era of effective ART and added the

new condition of asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment.]

10. Power C, Selnes OA, Grim JA, McArthur JC. The HIV dementia scale: a rapid screening test. J.

Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 1995; 8:273278. [PubMed: 7859139]

11. Sacktor N, Wong M, Nakasujja N, et al. The International HIV Dementia Scale: a new rapid

screening test for HIV dementia. AIDS. 2005; 19:13671374. [PubMed: 16103767]

12. Bergner M, Bobbitt RA, Carter WB, Gilson BS. The sickness impact profile development and final

revision of a health status measure. Med. Care. 1981; 19:787805. [PubMed: 7278416]

13. McNair, DM.; Kahn, RJ. The Cognitive Difficulties Scale.. In: Crook, T.; Ferris, S.; Bartus, R.,

editors. Assessment in Geriatric Psychopharmacology. Mark Powley Associates; CN, USA: 1983.

p. 137-143.

14. Wu AW, Rubin HR, Mathews WC, et al. A health status questionnaire using 30 items from the

medical outcomes study. Med. Care. 1991; 29:786798. [PubMed: 1875745]

15. Knippels HMA, Goodkin K, Weiss JJ, Wilkie FL, Antoni MH. The importance of cognitive selfreport in early HIV-1 infection: validation of a cognitive functional status subscale. AIDS. 2002;

16:259267. [PubMed: 11807311] [Demonstrates that a brief self-report measure of

neurocognitive functioning could provide valid data similar to those provided by formal

neuropsychological testing, suggesting that the use of such self-report screening measures could

be effectively applied in resource-limited settings both nationally and internationally.]

16. Lowenstein, DA.; Bates, BC. Manual for Administration and Scoring of the Direct Assessment of

Functional Status Scale in Older Adults (DAFS). Mt Sinai Medical Center; FL, USA: 1992.

Neuropsychiatry (London). Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 01.

Goodkin et al.

Page 10

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

17. Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, Jeste DV. UCSD performance-based skills

assessment: development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill

adults. Schizophr. Bull. 2001; 27:235245. [PubMed: 11354591]

18. Law WA, Mapou RL, Roller TL, Martin A, Nannis ED, Temoshok LR. Reaction time slowing in

HIV-1-infected individuals: role of preparatory interval. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 1995;

17:122133. [PubMed: 7608294]

19. Mirsattari SM, Power C, Nath A. Parkinsonism with HIV infection. Mov. Disord. 1998; 13:684

689. [PubMed: 9686775] [Demonstrates that the domain of motor function is explicitly relevant

to the presentation of HAND and is specific for the predilection of HIV for the basal ganglia,

which supports the need for HIV-specific diagnostic criteria for neurocognitive disorders.]

20. Rottenberg D, Moeller J, Strother SC, et al. The metabolic pathway of the AIDS dementia

complex. Ann. Neurol. 1987; 22:700706. [PubMed: 3501695]

21. Arendt G, Hefter H, Hilperath F, von Giesen HJ, Strohmeyer G, Freund HJ. Motor analysis

predicts progression in HIV-associated brain disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 1994; 123:180185.

[PubMed: 8064312]

22. Jack CR, Albert MS, Knopman DS, et al. Introduction to the recommendations from the National

Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer's Association Workgroup on Diagnostic Guidelines for

Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011; 7(3):257262. [PubMed: 21514247]

23. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's

disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer's Association

Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2011; 7(3):263269. [PubMed: 21514250]

24. Sperling RA, Aisen PA, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's

disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer's Association

Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2011; 7(3):280292. [PubMed: 21514248]

25. Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to

Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging Alzheimer's

Association Workgroups on Diagnostic Guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement.

2011; 7(3):270279. [PubMed: 21514249]

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Neuropsychiatry (London). Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 01.

Goodkin et al.

Page 11

Practice points

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Use HIV-specific diagnostic terminology to complement those of the Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) for the diagnosis of HIVassociated neurocognitive disorders (HAND).

Rely upon formal neuropsychological testing, whenever possible, for

documentation of the presence of neurocognitive impairment as a criterion for the

diagnoses of HAND.

Use a quantified cut-off based on neuropsychological testing to generate a

standardized designation for the documentation of the presence of HIV-associated

neurocognitive impairment.

Use a minimum of two impaired domains to qualify for the documentation of the

presence of HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment.

Include information processing speed and motor function but exclude social

cognition as separate domains to be assessed for the documentation of the presence

of HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Use documentation of any type of changes in activities of daily living (not solely

changes involving independence) that are related to HIV-associated neurocognitive

impairment as documentation for the functional status decline required for HAND

diagnoses.

Always rule out general medical illnesses, neurological diseases and psychiatric

disorders that might confound the diagnoses of HAND prior to making the diagnoses

definitive.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Neuropsychiatry (London). Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 01.

Goodkin et al.

Page 12

Table 1

DSM-5

Frascati conference-based revision of AAN criteria

Major neurocognitive disorder

HIV-associated dementia

A.Evidence of significant cognitive decline from a previous level

of performance in one or more of the domains outlined in the text

based on:

1.Reports by the patient or a knowledgeable informant, or

observation by the clinician, of clear decline in specific abilities as

outlined for specific domains in the text; and:

2.Clear deficits in objective assessment of the relevant domain

(typically >2 SD below the mean [or below the 2.5th percentile] of

an appropriate reference population [i.e., age, gender, education,

premorbid intellect and culturally adjusted])

B.The cognitive deficits are sufficient to interfere with

independence (e.g., at a minimum requiring assistance with

instrumental activities of daily living [i.e., more complex tasks

such as finances or managing medications])

C.The cognitive deficits do not occur exclusively in the context of

a delirium

D.The cognitive deficits are not wholly or primarily attributable to

another axis I disorder (e.g., major depressive disorder or

schizophrenia)

A.Marked acquired impairment in cognitive functioning, involving at

least two ability domains; typically the impairment is in multiple

domains, especially in the learning of new information, slowed

information processing and defective attention/concentration. The

cognitive impairment must be ascertained by neuropsychological testing

with at least two domains being 2 SD or greater below that of

demographically corrected means

B.The cognitive impairment produces marked interference with day-today functioning (work, home life and social activities)

C.The pattern of cognitive impairment does not meet criteria for delirium

D.There is no evidence of another, pre-existing cause for the dementia

(e.g., other CNS infection, CNS neoplasm, cerebrovascular disease, preexisting neurologic disease or severe substance abuse compatible with

CNS disorder)

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Minor neurocognitive disorder

HIV-associated mild neurocognitive disorder

A.Evidence of minor cognitive decline from a previous level of

performance in one or more of the domains outlined in the text

based on:

1.Reports by the patient or a knowledgeable informant, or

observation by the clinician, of minor levels of decline in specific

abilities as outlined for the specific domains in the text. Typically,

these will involve greater difficulty performing these tasks or the

use of compensatory strategies;

2.Mild deficits on objective cognitive assessment (typically 12 SD

below the mean [or in the 2.516th percentile] of an appropriate

reference population [i.e., age, gender, education, premorbid

intellect and culturally adjusted]). When serial measurements are

available, a significant (e.g., 0.5 SD) decline from the patient's own

baseline would serve as more definitive evidence of decline

B.The cognitive deficits are not sufficient to interfere with

independence (Instrumental Activities of Daily Living are

preserved), but greater effort and compensatory strategies may be

required to maintain independence

C.The cognitive deficits do not occur exclusively in the context of

a delirium

D.The cognitive deficits are not wholly or primarily attributable to

another axis I disorder (e.g., major depressive disorder or

schizophrenia)

1.Acquired impairment in cognitive functioning, involving at least two

ability domains, documented by performance of at least 1 SD below the

mean for age/education-appropriate norms on standardized

neuropsychological tests. The neuropsychological assessment must

survey at least the following abilities: verbal/language, attention/working

memory, abstraction/executive, memory (learning and recall), speed of

information processing, sensoryperceptual and motor skills

2.The cognitive impairment produces at least mild interference in daily

functioning (at least one of the following):

a)Self-report of reduced mental acuity, inefficiency in work,

homemaking or social functioning;

b)Observation by knowledgeable others that the individual has

undergone at least mild decline in mental acuity with resultant

inefficiency in work, homemaking, or social functioning

3.The cognitive impairment does not meet criteria for delirium or

dementia

4.There is no evidence of another pre-existing cause for the mild

neurocognitive disorder. If the individual with suspected mild

neurocognitive disorder also satisfies criteria for a severe episode of

major depression with significant functional limitations or psychotic

features, or substance dependence, the diagnosis of mild neurocognitive

disorder should be deferred to a subsequent examination conducted at a

time when the major depression has remitted or at least 1 month after

cessation of substance use

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Criteria for neurocognitive disorders proposed for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5

and the Frascati conference-based revision of American Academy of Neurology criteria.

No equivalent criteria

HIV-associated asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment

1.Acquired impairment in cognitive functioning, involving at least two

ability domains, documented by performance of at least 1 SD below the

mean for age/education-appropriate norms on standardized

neuropsychological tests. The neuropsychological assessment must

survey at least the following abilities: verbal/language, attention/working

memory, abstraction/executive, memory (learning and recall); speed of

information processing, sensoryperceptual and motor skills

2.The cognitive impairment does not interfere with everyday functioning

3.The cognitive impairment does not meet criteria for delirium or

dementia

4.There is no evidence of another pre-existing cause for the

asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment

In DSM-IV criteria [2,3], there are currently no criteria for a diagnosis analogous to mild neurocognitive disorder of the Frascati conferencebased revision of the AAN criteria (with the exception of the research appendix).

AAN: American Academy of Neurology; DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; SD: Standard deviation.

Neuropsychiatry (London). Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 01.

You might also like

- DSM 5 DiagnosingDocument107 pagesDSM 5 DiagnosingMichel Haddad100% (1)

- DSM 5 TR What's NewDocument2 pagesDSM 5 TR What's NewRafael Gaede Carrillo100% (1)

- ADHD: Current Concepts and Treatments in Children and AdolescentsDocument21 pagesADHD: Current Concepts and Treatments in Children and AdolescentsZary GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Autism Spectrum Disorder Fact SheetDocument2 pagesAutism Spectrum Disorder Fact SheetprofjpcNo ratings yet

- 07 Clinical Assessment Diagnosis & TreatmentDocument39 pages07 Clinical Assessment Diagnosis & TreatmentSteven T.No ratings yet

- Proposed) Declaration of Factual Innocence Under Penal Code Section 851.8 and OrderDocument4 pagesProposed) Declaration of Factual Innocence Under Penal Code Section 851.8 and OrderBobby Dearfield100% (1)

- DSM 5 Mood DisorderDocument9 pagesDSM 5 Mood DisorderErlin IrawatiNo ratings yet

- Nikulin D. - Imagination and Mathematics in ProclusDocument20 pagesNikulin D. - Imagination and Mathematics in ProclusannipNo ratings yet

- 5e - Crafting - GM BinderDocument37 pages5e - Crafting - GM BinderadadaNo ratings yet

- Claim &: Change ProposalDocument45 pagesClaim &: Change ProposalInaam Ullah MughalNo ratings yet

- DSM-5 and Psychotic and Mood Disorders: George F. Parker, MDDocument9 pagesDSM-5 and Psychotic and Mood Disorders: George F. Parker, MDMonika LangngagNo ratings yet

- Aphasia TableDocument2 pagesAphasia TableFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- Grammar For TOEFLDocument23 pagesGrammar For TOEFLClaudia Alejandra B0% (1)

- Europe Landmarks Reading Comprehension Activity - Ver - 1Document12 pagesEurope Landmarks Reading Comprehension Activity - Ver - 1Plamenna Pavlova100% (1)

- (s5.h) American Bible Society Vs City of ManilaDocument2 pages(s5.h) American Bible Society Vs City of Manilamj lopez100% (1)

- Learner's Material: ScienceDocument27 pagesLearner's Material: ScienceCarlz BrianNo ratings yet

- Roberts, Donaldson. Ante-Nicene Christian Library: Translations of The Writings of The Fathers Down To A. D. 325. 1867. Volume 15.Document564 pagesRoberts, Donaldson. Ante-Nicene Christian Library: Translations of The Writings of The Fathers Down To A. D. 325. 1867. Volume 15.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNo ratings yet

- Material DisertatieDocument6 pagesMaterial DisertatievioletaNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia Trends in Diagnosis and TherapyDocument13 pagesSchizophrenia Trends in Diagnosis and TherapyDoc HadiNo ratings yet

- Journal of Psychosomatic Research: Katharina Schieber, Ines Kollei, Martina de Zwaan, Alexandra MartinDocument5 pagesJournal of Psychosomatic Research: Katharina Schieber, Ines Kollei, Martina de Zwaan, Alexandra MartinJuanNo ratings yet

- Guía de ParkinsonDocument7 pagesGuía de ParkinsonkarlunchoNo ratings yet

- Obsessive - Compulsive Personality Disorder: A Current ReviewDocument10 pagesObsessive - Compulsive Personality Disorder: A Current ReviewClaudia AranedaNo ratings yet

- B4 HAND DefinitionDocument13 pagesB4 HAND DefinitionFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- Apatia e ParkinsonDocument11 pagesApatia e ParkinsonFernanda NascimentoNo ratings yet

- Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2014 Gitlin 89 90Document3 pagesAust N Z J Psychiatry 2014 Gitlin 89 90KThreopusNo ratings yet

- Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2014 Carroll 90 1Document3 pagesAust N Z J Psychiatry 2014 Carroll 90 1KThreopusNo ratings yet

- Pressman Et Al 2021 Distinguishing Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia From Primary Psychiatric Disorders ADocument5 pagesPressman Et Al 2021 Distinguishing Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia From Primary Psychiatric Disorders AgyzuvlxsusyxdjcjtlNo ratings yet

- 996 FullDocument9 pages996 FullNovita WulandariNo ratings yet

- CAMDEX. A Standardised Instrument For The Diagnosis of MentalDocument13 pagesCAMDEX. A Standardised Instrument For The Diagnosis of MentalLeila CamilaNo ratings yet

- CIA 47367 Assessment of Cognitive Impairment in Patients With Parkinso 021214Document7 pagesCIA 47367 Assessment of Cognitive Impairment in Patients With Parkinso 021214ziropadjaNo ratings yet

- WFSBP Treatment Guidelines Dementia PDFDocument31 pagesWFSBP Treatment Guidelines Dementia PDFALLNo ratings yet

- Diedrich Voderholzer Review OCPD PrintDocument11 pagesDiedrich Voderholzer Review OCPD PrintAbid AliNo ratings yet

- DSM VDocument7 pagesDSM VPreeti ChouhanNo ratings yet

- DSM5 Clasification Diagnostic Criteria Changes PDFDocument7 pagesDSM5 Clasification Diagnostic Criteria Changes PDFlilomersNo ratings yet

- PDpsychosisDocument8 pagesPDpsychosismyosotysNo ratings yet

- Attention-De Ficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Conceptual DebateDocument7 pagesAttention-De Ficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Conceptual DebateCristinaNo ratings yet

- Review: Major Depressive Disorder in Dsm-5: Implications For Clinical Practice and Research of Changes From Dsm-IvDocument13 pagesReview: Major Depressive Disorder in Dsm-5: Implications For Clinical Practice and Research of Changes From Dsm-IvCarlos GardelNo ratings yet

- University of Nairobi Humanities and Social Sciences Faculty of Arts Department of Psychology Assignment Dsm-5 History and Development Haniel Gatumu Wilfred Kerambo C01/1018/2019 2oth August 2020Document8 pagesUniversity of Nairobi Humanities and Social Sciences Faculty of Arts Department of Psychology Assignment Dsm-5 History and Development Haniel Gatumu Wilfred Kerambo C01/1018/2019 2oth August 2020ElijahNo ratings yet

- Sensitivity and Specificity: DSM-IV Versus DSM-5 Criteria For Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument3 pagesSensitivity and Specificity: DSM-IV Versus DSM-5 Criteria For Autism Spectrum DisorderHaziq MarsNo ratings yet

- Articulo 3 Sesión 1 Visión General Reed Et Al 2018Document13 pagesArticulo 3 Sesión 1 Visión General Reed Et Al 2018manuel ñiqueNo ratings yet

- C4 Adjustment Disorder and Suicidal BehavioursDocument15 pagesC4 Adjustment Disorder and Suicidal BehavioursMilagros Saavedra RecharteNo ratings yet

- BaixadosDocument14 pagesBaixadosLanna RegoNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 13 04564Document16 pagesSustainability 13 04564daniellegarciaaaNo ratings yet

- Fpsyg 06 01108Document4 pagesFpsyg 06 01108Oana OrosNo ratings yet

- For Information Contact:: DSM-5 Is Planned For May 2013Document1 pageFor Information Contact:: DSM-5 Is Planned For May 2013Elyssa DurantNo ratings yet

- 2019 Acute and Transient Psychotic Disorders - Newer UnderstandingDocument11 pages2019 Acute and Transient Psychotic Disorders - Newer Understandingjuliana izquierdoNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Depression in Alzheimer's Disease and Validity of Research Diagnostic CriteriaDocument3 pagesPrevalence of Depression in Alzheimer's Disease and Validity of Research Diagnostic CriteriaEugenio OleaNo ratings yet

- Guidelines CIDPDocument9 pagesGuidelines CIDPTowhidulIslamNo ratings yet

- Ensefalitis Dan PsikosisDocument15 pagesEnsefalitis Dan PsikosisLhia PrisciliiaNo ratings yet

- Seminar: Jonathan Posner, Guilherme V Polanczyk, Edmund Sonuga-BarkeDocument13 pagesSeminar: Jonathan Posner, Guilherme V Polanczyk, Edmund Sonuga-BarkeCristinaNo ratings yet

- The Future Arrived: ViewpointDocument2 pagesThe Future Arrived: ViewpointDaniela Ocampo BoteroNo ratings yet

- Use of The Manual: Approach To Clinical Case FormulationDocument9 pagesUse of The Manual: Approach To Clinical Case FormulationIrma YuiNo ratings yet

- 2014 - Faraone Curr Psychiatry Rep 2014 Biomarkers in The Diagnosis ADHDDocument21 pages2014 - Faraone Curr Psychiatry Rep 2014 Biomarkers in The Diagnosis ADHDRuth GaspariniNo ratings yet

- Discuss Issues Associated With The Classification andDocument3 pagesDiscuss Issues Associated With The Classification andAkshay NayakNo ratings yet

- Feighner Et Al (1972) - Diagnostic Criteria For Use in Psychiatric ResearchDocument7 pagesFeighner Et Al (1972) - Diagnostic Criteria For Use in Psychiatric ResearchEmily RedmanNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0010440X15302169 MainDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S0010440X15302169 Mainlidia torres rosadoNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Inggris 1Document28 pagesJurnal Inggris 1ErinaTandirerungNo ratings yet

- A Study of Co-Morbidity in Mental RetardationDocument9 pagesA Study of Co-Morbidity in Mental RetardationijhrmimsNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Guideline: Assessment and Management of Psychiatric Disorders in Individuals With MSDocument9 pagesEvidence-Based Guideline: Assessment and Management of Psychiatric Disorders in Individuals With MSChon ChiNo ratings yet

- Brit.J. Psychiat. (1979), 135,438â "443Document7 pagesBrit.J. Psychiat. (1979), 135,438â "443feraresNo ratings yet

- The Neurologic Examination in Adult Psychiatry: From Soft Signs To Hard ScienceDocument10 pagesThe Neurologic Examination in Adult Psychiatry: From Soft Signs To Hard ScienceMario AndersonNo ratings yet

- (C1C2) Herpertz (2017)Document13 pages(C1C2) Herpertz (2017)sydhpzsb7dNo ratings yet

- Daum 2013Document12 pagesDaum 2013warlopNo ratings yet

- Neurocognitive Deficits in Depression Review 2021Document24 pagesNeurocognitive Deficits in Depression Review 2021bilchi.1699911No ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument9 pagesAssignmentIshita AdhikariNo ratings yet

- Ijpsym - Ijpsym 464 18Document6 pagesIjpsym - Ijpsym 464 18Roberto Alexis Molina CampuzanoNo ratings yet

- Alhadi-2017-An-arabic-translation-reliability-a PDFDocument9 pagesAlhadi-2017-An-arabic-translation-reliability-a PDFnavquaNo ratings yet

- INGLES Demencia Relacionada Con El Alcohol y Deterioro Neurocognitivo Un Estudio de RevisiónDocument9 pagesINGLES Demencia Relacionada Con El Alcohol y Deterioro Neurocognitivo Un Estudio de RevisiónandreaNo ratings yet

- Dimensional PsychopathologyFrom EverandDimensional PsychopathologyMassimo BiondiNo ratings yet

- The Burden of Adult ADHD in Comorbid Psychiatric and Neurological DisordersFrom EverandThe Burden of Adult ADHD in Comorbid Psychiatric and Neurological DisordersNo ratings yet

- Word Academician Thesis 1.1Document30 pagesWord Academician Thesis 1.1khairul_aNo ratings yet

- MRS NotesDocument9 pagesMRS NotesFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- HIV-associated Neurocognitive Disorders: Review Open AccessDocument10 pagesHIV-associated Neurocognitive Disorders: Review Open AccessFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- Ovid - Virology, Immunology and Pathology of Human Rabies During TreatmentDocument10 pagesOvid - Virology, Immunology and Pathology of Human Rabies During TreatmentFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- B4 HAND DefinitionDocument13 pagesB4 HAND DefinitionFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- Vancouver Style PDFDocument25 pagesVancouver Style PDFwewwewNo ratings yet

- Steyerberg Prediction Modeling 7 Steps Jan10Document45 pagesSteyerberg Prediction Modeling 7 Steps Jan10Fajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- S Pss Moving From ExcelDocument2 pagesS Pss Moving From ExcelAnggah KhanNo ratings yet

- Neurogenic Pulmonary EdemaDocument12 pagesNeurogenic Pulmonary EdemaFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- Penelitian DR Lilik - JoiDocument16 pagesPenelitian DR Lilik - JoiFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- Gio G Karaki 2013Document13 pagesGio G Karaki 2013Fajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- PDF Callosal Disconnection J StrokeDocument5 pagesPDF Callosal Disconnection J StrokeFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- The Neurology of Eclampsia: Some Observations: Views and ReviewsDocument8 pagesThe Neurology of Eclampsia: Some Observations: Views and ReviewsFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- Hav Steen 2014Document7 pagesHav Steen 2014Fajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- 6.3 Area Under Any Normal Curve: Normal Curves and Sampling DistributionsDocument15 pages6.3 Area Under Any Normal Curve: Normal Curves and Sampling DistributionsFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- WNL204606Document9 pagesWNL204606Fajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone HivDocument9 pagesJournal Pone HivFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- Arv HivDocument5 pagesArv HivFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- Role of Clinical and Paraclinical Manifestations of Methanol Poisoning in Outcome PredictionDocument6 pagesRole of Clinical and Paraclinical Manifestations of Methanol Poisoning in Outcome PredictionFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- Seizure Prophylaxis in TBIDocument8 pagesSeizure Prophylaxis in TBIvinodksahuNo ratings yet

- Revue Neurologique Volume 169 Issue 10 2013 (Doi 10.1016/j.neurol.2013.07.022) Debette, S. - Vascular Risk Factors and Cognitive DisordersDocument8 pagesRevue Neurologique Volume 169 Issue 10 2013 (Doi 10.1016/j.neurol.2013.07.022) Debette, S. - Vascular Risk Factors and Cognitive DisordersFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- Cognitive HivDocument14 pagesCognitive HivFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- Auto Testing PatientsDocument2 pagesAuto Testing PatientsFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- Picone 2015Document14 pagesPicone 2015Fajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- Guns Tad 2008Document6 pagesGuns Tad 2008Fajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- SDTM Qs - Mhis-Nacc v1 Public DomainDocument7 pagesSDTM Qs - Mhis-Nacc v1 Public DomainFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Risk Factors On The Duration of Cognitive ImpairmentDocument28 pagesThe Effect of Risk Factors On The Duration of Cognitive ImpairmentFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- PT - Science 5 - Q1Document4 pagesPT - Science 5 - Q1Jomelyn MaderaNo ratings yet

- Ain Tsila Development Main EPC Contract A-CNT-CON-000-00282: Visual Inspection Test Procedure B-QAC-PRO-210-39162Document14 pagesAin Tsila Development Main EPC Contract A-CNT-CON-000-00282: Visual Inspection Test Procedure B-QAC-PRO-210-39162ZaidiNo ratings yet

- K3VG Spare Parts ListDocument1 pageK3VG Spare Parts ListMohammed AlryaniNo ratings yet

- 2017 - The Science and Technology of Flexible PackagingDocument1 page2017 - The Science and Technology of Flexible PackagingDaryl ChianNo ratings yet

- Debarchana TrainingDocument45 pagesDebarchana TrainingNitin TibrewalNo ratings yet

- SANDHU - AUTOMOBILES - PRIVATE - LIMITED - 2019-20 - Financial StatementDocument108 pagesSANDHU - AUTOMOBILES - PRIVATE - LIMITED - 2019-20 - Financial StatementHarsimranSinghNo ratings yet

- Outline - Criminal Law - RamirezDocument28 pagesOutline - Criminal Law - RamirezgiannaNo ratings yet

- DMemo For Project RBBDocument28 pagesDMemo For Project RBBRiza Guste50% (8)

- 9francisco Gutierrez Et Al. v. Juan CarpioDocument4 pages9francisco Gutierrez Et Al. v. Juan Carpiosensya na pogi langNo ratings yet

- Hydraulics Experiment No 1 Specific Gravity of LiquidsDocument3 pagesHydraulics Experiment No 1 Specific Gravity of LiquidsIpan DibaynNo ratings yet

- KalamDocument8 pagesKalamRohitKumarSahuNo ratings yet

- Pon Vidyashram Group of Cbse Schools STD 8 SCIENCE NOTES (2020-2021)Document3 pagesPon Vidyashram Group of Cbse Schools STD 8 SCIENCE NOTES (2020-2021)Bharath Kumar 041No ratings yet

- Army Public School Recruitment 2017Document9 pagesArmy Public School Recruitment 2017Hiten BansalNo ratings yet

- Sarcini: Caiet de PracticaDocument3 pagesSarcini: Caiet de PracticaGeorgian CristinaNo ratings yet

- De Luyen Thi Vao Lop 10 Mon Tieng Anh Nam Hoc 2019Document106 pagesDe Luyen Thi Vao Lop 10 Mon Tieng Anh Nam Hoc 2019Mai PhanNo ratings yet

- La Fonction Compositionnelle Des Modulateurs en Anneau Dans: MantraDocument6 pagesLa Fonction Compositionnelle Des Modulateurs en Anneau Dans: MantracmescogenNo ratings yet

- 40+ Cool Good Vibes MessagesDocument10 pages40+ Cool Good Vibes MessagesRomeo Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Order of Magnitude-2017Document6 pagesOrder of Magnitude-2017anon_865386332No ratings yet

- " Thou Hast Made Me, and Shall Thy Work Decay?Document2 pages" Thou Hast Made Me, and Shall Thy Work Decay?Sbgacc SojitraNo ratings yet

- Electronic ClockDocument50 pagesElectronic Clockwill100% (1)

- CrisisDocument13 pagesCrisisAngel Gaddi LarenaNo ratings yet