Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pulmonary Metastasis 2

Uploaded by

raisamentariOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pulmonary Metastasis 2

Uploaded by

raisamentariCopyright:

Available Formats

Pulmonary Metastasis

How often is the lung the site of metastases?

What are the means by which the tumor cells reach the lung?

Is it common to see the lung as the only site of metastasis?

What are the different metastatic patterns?

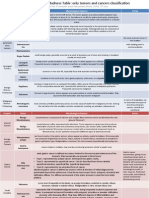

Can one predict the probable primary source from a given roentgen

pattern?

What are the modes of presentation?

What is the best way to make a diagnosis?

What is the best way to care for it?

Multiple Lesions

Multiple discrete lung lesions occur due to widely disseminated

hematogenous metastasis.

The pattern can vary from:

diffuse micronodular shadows resembling miliary disease, or

to multiple large well defined masses cannon balls.

Occasionally, cavitation or calcification can be noted.

Symptoms:

Due to the interstitial location, these lesions are often asymptomatic.

Cough and hemoptysis are the usual symptoms.

Needle aspiration or transbronchial biopsy would be the procedure of

choice for confirmation of the nature of the lesion.

Treatment:

Chemotherapy is the choice when the tumor is responsive.

Occasional surgical resection of multiple lesions were attempted with

some reported success.

In refractory hemoptysis, selective occlusion of bronchial arteries by

Teflon is a consideration.

Cannon Balls:

Neoplasms with rich vascular supply draining directly into the systemic

venous system often present in this fashion.

Miliary Pattern: This presentation is seen in patients with the following:

Thyroid carcinoma

Renal cell carcinoma

Sarcoma of the bone

Trophoblastic disease

Cavitating Lesions:

Cavitation is identified in 4% of metastatic deposits and, as with primary

bronchial carcinoma, is more likely in squamous cell lesions.

Colon, anus, cervix, breast and larynx account for 69% of such

occurrences.

Generally, small thin walled metastases usually indicate a primary site

in the head or neck, where as most large, thick walled secondaries

arise from the gastrointestinal tract.

Avascular necrosis of the lesion secondary to vascular occlusion, is the

presumed mechanism for cavitation.

Calcification:

Calcification or ossification is rarely visible in metastasis to the thorax.

Calcification of metastasis from ovarian, thyroid, breast and mucin

producing gastrointestinal neoplasms.

Calcification in lymphomatous nodes has most often occurred

following therapy.

Lung metastasis may also calcify following therapy.

Almost all calcified or ossified lung metastasis occurring prior to therapy

are due to osteosarcoma or chondrosarcoma.

Isolated cases of such metastasis have also been reported with

synovial sarcoma and giant cell tumor of the bone.

Solitary Pulmonary Nodule

Pulmonary metastases clinically present as a solitary pulmonary

nodule.

Similar to other solitary pulmonary nodular lesions, these are detected

by routine chest x-rays.

Of the solitary pulmonary nodular lesions, solitary metastases accounts

for less than 3% of cases.

Colon, chest, sarcoma, melanoma and genitourinary malignancies

account for 79% of such instances.

Solitary metastatic lesion can precede, follow or appear concomitantly

with the malignancy.

Diagnostic Strategy:

When it appears concomitantly or following definitive therapy of the

primary, thin needle aspiration of the lesion is probably the best

procedure to establish the nature of the lesion.

CT scans are superior to whole lung tomograms in evaluating the

presence of other occult metastatic lesions.

When the solitary pulmonary metastasis precedes clinical recognition of

the primary, standard management of the solitary pulmonary nodular

lesion should follow.

This clinical presentation accounts for less than 1% and routine search

for primary is not recommended.

Treatment:

Surgical resection of single metastasis should be considered:

when the primary tumor is resectable

no other organ metastasis is evident

and no effective alternate therapy is available

Surgical resection of solitary lung lesions occurring a few years

following curative resection of primary have a better prognosis than the

lesions that manifest concomitantly with the primary tumor.

Endobronchial Lesion

Endobronchial metastases are rare in comparison with parenchymal

deposits and account for 2% of patients who died from solid neoplasms.

Diagnostic challenge:

They simulate primary bronchogenic carcinoma in clinical presentation

and are often difficult to distinguish, even pathologically.

Simultaneous occurrence of two primaries is a difficult differential to

settle on many occasions.

The usual roentgen findings are bronchial obstruction and obstructive

atelectasis or pneumonia.

The endobronchial lesion may have characteristic pigment on

bronchoscopy in metastatic melanoma.

Patients may complain of persistent cough, hemoptysis, wheezing and

may have normal chest x-rays.

Kidney, colon, breast sarcoma and melanoma account for 67% of

the cases.

The metastases is located subepithelially and is due to hematogenous

metastases through the bronchial arteries.

It is unlikely to be secondary to endobronchial drop metastasis as tumor

cells often require fibrin thrombin to impact. The cough and mucociliary

reflex may efficiently clear aspirated cells.

Palliative radiation or resection becomes necessary if the patient has

hemoptysis or refractory obstructive pneumonitis.

Tracheal Metastasis

When the lesion is located in the trachea, patients will present with

severe wheezing and have normal chest x-ray findings.

Lymphadenopathy

The incidence of lymph node metastasis is high with extrathoracic

primaries, as well as bronchogenic carcinoma.

Autopsy incidence related to various primaries range from 20-60%.

However, the reported incidence and radiographically visible

lymphadenopathy vary greatly.

Radiographically visible enlargement is probably found in less than 5%

of all patients with extrathoracic primary neoplasms.

Head and neck and genitourinary tract neoplasms most often cause

visible intrathoracic enlargement followed by malignant melanoma and

breast carcinoma.

Diagnostic challenge

Lymphadenopathy may be hilar, mediastinal or both.

This opposed to sarcoidosis, which rarely causes mediastinal nodular

enlargement without hilar enlargement.

Lymph node metastasis is not always associated with lung metastasis.

The radiographic appearance may, therefore, be indistinguishable from

sarcoid, non-infectious granulomatous disease, lymphoma, leukemia or

a primary mediastinal tumor.

Diagnostic problems arise in the minority of patients who do not have

known primary neoplasms.

Asymptomatic patients with symmetric hilar enlargement usually have

sarcoidosis.

Metastatic disease may cause bilateral hilar enlargement. However,

these patients are usually symptomatic.

Anterior mediastinal node masses are common in lymphoma but rare in

sarcoid, as seen on chest radiographs.

Pleural Effusion

Pleural effusion is one of the common metastatic patterns.

The effusions often tend to be massive, recurrent and associated with

shortness of breath.

This pattern is associated with extensive underlying lung and systemic

metastases.

Most patients expire within three months.

Malignant effusions account for more than 50% of exudative pleural

effusions.

Lung, breast, stomach and ovary account for 81% of cases.

Pleural biopsy and fluid cytology establish the malignant nature of the

process.

Pleural sclerosis with tetracycline instillation is the palliative procedure

of choice in problem effusions.

Pleural Masses

Significant pleural masses can exist without recognition (as in the

adjoining CXR), even in the absence of pleural effusion.

Iatrogenic pneumothorax facilitates visualization of pleural masses.

CT scan can reveal pleural masses that are not seen on routine x-rays.

Thymoma, multiple myeloma and cystadenocarcinoma lung are

reported to give such a metastatic pattern.

Spontaneous pneumothorax

Pneumothorax occurring secondary to pulmonary metastasis is rare.

This mode of presentation occurs secondary to necrosis of subpleurally located metastas

Cavitating sarcoma is reported to present in this manner.

In some instances, the subpleural metastases are not sufficiently large enough to be reco

Chest Wall Lesion

Metastatic lesions to ribs are common.

Occasionally, these lesions expand and encroach on the lung,

masquerading as a lung lesion.

The characteristic extrapleural signs, namely the peripheral location,

indistinct outer margin with a sharp inner margin and biconcave edges

help point towards the true location of the lesion.

Recognition of such lesions focuses ones attention to the ribs and

facilitates easy biopsy by percutaneous techniques.

Alveolar Pattern

Alveolar form of metastases is relatively rare and is often an

unrecognized form of metastatic pattern.

Histologically, they are indistinguishable from primary alveolar cell lung

carcinoma.

Pancreatic carcinoma is the most common primary to present in such

a fashion.

Metastatic liposarcoma and laryngeal carcinoma have occasionally

been reported to give a similar pattern.

The metastatic lesions from choriocarcinoma also have features of

alveolar pattern.

However, this is secondary to bleeding into the lesions rather then due

to tumor, per se.

Interstitial Pattern

Less than 10% of lung metastases have a lymphangitic pattern.

Pathogenesis:

Lymphangitic metastatic disease in the lung is generally believed to be

the result of tumor spread along the perivascular lymphatic after initial

deposition of tumor embolus in a pulmonary capillary by hematogenous

route.

There is evidence that gastric carcinoma is an exception to this with

direct lymphatic extension occurring from the abdomen to chest, across

the diaphragm.

The stomach, lung and breast account for 80% of cases.

The large majority of patients with unilateral diseases have

bronchogenic carcinoma.

Most patients have dyspnea with or without cough. Initially, symptoms

can be mild.

Diagnostic challenge:

There is evidence of lung tissue disease on chest radiographs: small

linear and nodular densities, reticular nodular pattern, septal lines.

The appearance is similar to interstitial changes seen in pulmonary

edema, pneumoconiosis, usual interstitial pneumonitis or sarcoid.

There is frequent pleural effusion on hilar lymphadenopathy.

Some symptomatic patients have normal radiographs.

Transbronchial lung biopsy or needle aspiration can provide tissue for

diagnosis.

In the absence of suitable chemotherapy, only symptomatic therapy can

be provided.

Most patients become severely dyspneic and expire within a few

months.

Subacute Cor Pulmonale

This form of presentation occurs when small subliminal tumor deposits obstruct a sufficien

The spectrum of pulmonary symptoms is identically to thromboembolism.

Patients are in prolonged respiratory distress with normal chest x-ray, and with or withou

Choriocarcinoma, hepatoma, breast and stomach tumors account for most of the prim

This entity should be considered in a female with severe respiratory distress with a histor

When recognized, chemotherapy offers a favorable prognosis in patients with choriocarci

Prognosis is poor with other primary malignancies.

Conclusion

Lung metastases occur in approximately 30% of malignant disease

cases.

Frequently, it is the presenting manifestation and search for the primary

is lengthy and cumbersome.

The roentgen patterns of thoracic metastases vary. Awareness of the

common primaries presenting with a metastatic pattern facilitates the

search for the source.

The venous and lymphatic drainage of the organ and the cell type are

some variables that seem to determine the metastatic pattern.

Each metastatic pattern has a unique clinical presentation because of

its locale and extent.

Each pattern raises a distinct differential diagnosis, differs in the best

diagnostic procedure and the choice of therapeutic modality.

You might also like

- Tumores Solitarios Pulmonares InusualesDocument8 pagesTumores Solitarios Pulmonares InusualesSasha de la CruzNo ratings yet

- Pulmonary Metastasis and PneumoniaDocument22 pagesPulmonary Metastasis and PneumoniazixdiddyNo ratings yet

- Lung Tumors: Dr. Mohammed Natiq Pulmonary PathologyDocument4 pagesLung Tumors: Dr. Mohammed Natiq Pulmonary PathologyNoor AL Deen SabahNo ratings yet

- Pulmonary MetastasesDocument8 pagesPulmonary MetastasesJunlianty UnhyNo ratings yet

- Detecting Lung Cancer with Imaging TestsDocument55 pagesDetecting Lung Cancer with Imaging TestsAjengNo ratings yet

- Imaging in Bronchogenic CarcinomaDocument86 pagesImaging in Bronchogenic CarcinomaSandipan NathNo ratings yet

- SGL5 - HaemoptysisDocument73 pagesSGL5 - HaemoptysisDarawan MirzaNo ratings yet

- Carcinoma Lung and Lymhangitis Carcinomatosa 2Document43 pagesCarcinoma Lung and Lymhangitis Carcinomatosa 2Jagan MaxNo ratings yet

- Bronchogenic Malignancy and Metastatic Disease: Hilar MassesDocument4 pagesBronchogenic Malignancy and Metastatic Disease: Hilar MassesTira SariNo ratings yet

- Lung TumorsDocument29 pagesLung Tumorssamar yousif mohamedNo ratings yet

- Lung Cancer 11Document106 pagesLung Cancer 11api-19916399No ratings yet

- Lung Anatomy, Cancers and MesotheliomaDocument60 pagesLung Anatomy, Cancers and MesotheliomaKatNo ratings yet

- Bronchogenic Carcinoma Diagnosis GuideDocument55 pagesBronchogenic Carcinoma Diagnosis GuidePandu AlanNo ratings yet

- Radiology Characteristics by Cell TypeDocument11 pagesRadiology Characteristics by Cell TypeCharm MeelNo ratings yet

- Data SCC From InternetDocument3 pagesData SCC From InternetristaniatauhidNo ratings yet

- Carcinoma of Lung LectureDocument37 pagesCarcinoma of Lung Lecturesadaf12345678No ratings yet

- 27 Mediastinal and Other Neoplasms Part 2 Other Lung NeoplasmsDocument25 pages27 Mediastinal and Other Neoplasms Part 2 Other Lung NeoplasmsjimmyneumologiaNo ratings yet

- Bronchogenic Carcinoma: Dr. Vineet ChauhanDocument49 pagesBronchogenic Carcinoma: Dr. Vineet ChauhanRaviNo ratings yet

- ChoriocarcinomaDocument26 pagesChoriocarcinomaManmat Swami100% (1)

- Lung TumorDocument27 pagesLung Tumorybezi15No ratings yet

- NAL Eoplasms: Jonathan S. ViernesDocument24 pagesNAL Eoplasms: Jonathan S. ViernesironNo ratings yet

- BENIGN LUNG TUMORSDocument16 pagesBENIGN LUNG TUMORSAbdul Mubdi ArdiansarNo ratings yet

- Malignant Epithelial Non-Odontogenic Tumors 2Document11 pagesMalignant Epithelial Non-Odontogenic Tumors 2samamustafa.2003No ratings yet

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma-Well DifferentiatedDocument4 pagesSquamous Cell Carcinoma-Well DifferentiatedYukankolmi OyoNo ratings yet

- Metastatic TumorsDocument43 pagesMetastatic TumorsRadio ResidentNo ratings yet

- Practice Essentials: View Media GalleryDocument8 pagesPractice Essentials: View Media GallerywzlNo ratings yet

- ملخص د. سامر رستم - الجهاز التنفسي - تشريح مرضي خاصDocument3 pagesملخص د. سامر رستم - الجهاز التنفسي - تشريح مرضي خاصd-khaldounNo ratings yet

- Hoffman 2000Document7 pagesHoffman 2000jenny12No ratings yet

- Background: Bladder Cancer Colon Cancer Breast Cancer Prostate Cancer Wilms Tumor NeuroblastomaDocument4 pagesBackground: Bladder Cancer Colon Cancer Breast Cancer Prostate Cancer Wilms Tumor Neuroblastomafitri ramadhan hasbiNo ratings yet

- Review For The 2° Semester Exam Alessandro Mo6a, UVVG, 3 YearDocument9 pagesReview For The 2° Semester Exam Alessandro Mo6a, UVVG, 3 Yeardjxela89No ratings yet

- Case Analysis DR RinaDocument30 pagesCase Analysis DR RinaCindy PrayogoNo ratings yet

- Normal Mediastinal Anatomy, Pathologies and Diagnostic MethodsDocument9 pagesNormal Mediastinal Anatomy, Pathologies and Diagnostic MethodsJuma AwarNo ratings yet

- TopoDocument15 pagesTopoabha upmanyuNo ratings yet

- MR CXR CoarseDocument4 pagesMR CXR CoarseMia AndikaNo ratings yet

- Thyroid TumoursDocument106 pagesThyroid TumoursJodene Rose RojasNo ratings yet

- Neoplasms Ear CanalDocument12 pagesNeoplasms Ear CanalannaNo ratings yet

- 5 Tumor Sistem PernafasanDocument66 pages5 Tumor Sistem PernafasanFaerusNo ratings yet

- Soft Tissue TumorDocument67 pagesSoft Tissue TumorVincentius Michael WilliantoNo ratings yet

- High Resolution Computed Tomography of The LungsDocument26 pagesHigh Resolution Computed Tomography of The LungsTessa AcostaNo ratings yet

- Lung Cancer: Understanding the PathophysiologyDocument70 pagesLung Cancer: Understanding the PathophysiologyLisa KurniaNo ratings yet

- Tumor Suzne Zlijezde AAODocument4 pagesTumor Suzne Zlijezde AAOJovan PopovićNo ratings yet

- Conway Lien, MD Mahesh R Patel, MDDocument8 pagesConway Lien, MD Mahesh R Patel, MDBoby SuryawanNo ratings yet

- Q Banks Notes GUDocument30 pagesQ Banks Notes GURazan AlayedNo ratings yet

- Tumor MediastinumDocument12 pagesTumor MediastinumTheodore LiwonganNo ratings yet

- Neoplasms of Nose & para Nasal SinusesDocument171 pagesNeoplasms of Nose & para Nasal SinusesJulian HobbsNo ratings yet

- Topic: Reporters: LN1, LN2, LN3 - Date of ReportDocument4 pagesTopic: Reporters: LN1, LN2, LN3 - Date of ReportDesa RefuerzoNo ratings yet

- Oral SCCDocument10 pagesOral SCCيونس حسينNo ratings yet

- Aruns PL - Ade FinalDocument9 pagesAruns PL - Ade FinaldrarunsinghNo ratings yet

- Current Controversies in The Management of Malignant Parotid TumorsDocument8 pagesCurrent Controversies in The Management of Malignant Parotid TumorsDirga Rasyidin LNo ratings yet

- MeningiomaDocument7 pagesMeningiomaLili HapverNo ratings yet

- 2.lung NeoplasmDocument50 pages2.lung Neoplasmtesfayegermame95.tgNo ratings yet

- Lower Respirasi: DR - Dyah Marianingrum, Mkes, SP - PADocument34 pagesLower Respirasi: DR - Dyah Marianingrum, Mkes, SP - PAsarah rajaNo ratings yet

- Chest Imaging PT 2Document70 pagesChest Imaging PT 2Andrei RomanNo ratings yet

- Oropharyngeal TumoursDocument8 pagesOropharyngeal Tumourseldoc13No ratings yet

- TCVSDocument10 pagesTCVSDianne GalangNo ratings yet

- HEAD AND NECK 1.robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease ReviewerDocument14 pagesHEAD AND NECK 1.robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease ReviewerSeff Causapin100% (1)

- PAROTID GLAND NEOPLASM IMAGINGDocument107 pagesPAROTID GLAND NEOPLASM IMAGINGigorNo ratings yet

- Fast Facts: Advanced Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma for Patients and their Supporters: Information + Taking Control = Best OutcomeFrom EverandFast Facts: Advanced Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma for Patients and their Supporters: Information + Taking Control = Best OutcomeNo ratings yet

- Anal Cancer, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandAnal Cancer, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- 2006 89 Canine and Feline Nasal NeoplasiaDocument6 pages2006 89 Canine and Feline Nasal NeoplasiaFelipe Guajardo HeitzerNo ratings yet

- Ijphrd Journal July-Sep 2013 - 06-06-213 PDFDocument307 pagesIjphrd Journal July-Sep 2013 - 06-06-213 PDFp1843dNo ratings yet

- The Use of Artificial Dermis in The Reconstruction.9Document9 pagesThe Use of Artificial Dermis in The Reconstruction.9Resurg ClinicNo ratings yet

- Cancer and Oncology Nursing NCLEX Practice Quiz #1 (56 Questions)Document1 pageCancer and Oncology Nursing NCLEX Practice Quiz #1 (56 Questions)loren fuentesNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Imaging Pathways ArticleDocument5 pagesDiagnostic Imaging Pathways Articlemashuri muhammad bijuriNo ratings yet

- Clinical Ophthalmic Oncology Eyelid and Conjunctival Tumors - Jacob Pe'Er Arun D. Singh 3ed 2019Document314 pagesClinical Ophthalmic Oncology Eyelid and Conjunctival Tumors - Jacob Pe'Er Arun D. Singh 3ed 2019Barbara MarcussoNo ratings yet

- Case Study-Lung EsophagusDocument38 pagesCase Study-Lung Esophagusapi-543077883No ratings yet

- Types of CancerDocument3 pagesTypes of CancerStudent FemNo ratings yet

- Everything You Need to Know About Breast CancerDocument27 pagesEverything You Need to Know About Breast Cancerrikshya k c100% (3)

- Endometrial Cancer Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument9 pagesEndometrial Cancer Diagnosis and TreatmentAhmed Butt100% (1)

- Reading TestDocument196 pagesReading TestKrisselle Ann TanNo ratings yet

- Ck7 Negative, Ck20 Positive Gastric Cancer: More Common Than You Might ThinkDocument2 pagesCk7 Negative, Ck20 Positive Gastric Cancer: More Common Than You Might ThinkAustin Publishing GroupNo ratings yet

- AJCC Cancer Staging Manual Stomach 7theditionDocument3 pagesAJCC Cancer Staging Manual Stomach 7theditionCamelia CalugariciNo ratings yet

- Malignant Disease of The JawsDocument26 pagesMalignant Disease of The JawsRawda NajjarNo ratings yet

- Soft Tissue CarcinomaDocument75 pagesSoft Tissue CarcinomaEfren Catimbang Jr.No ratings yet

- Causes of Death and Cancer TypesDocument22 pagesCauses of Death and Cancer TypesstevencongressNo ratings yet

- RhinologyDocument146 pagesRhinologydrsalasgNo ratings yet

- 3.1.5.3 Patologi Anatomi Sistem Urogenital Dan PayudaraDocument70 pages3.1.5.3 Patologi Anatomi Sistem Urogenital Dan PayudaraaiysahmirzaNo ratings yet

- 2016 EdBookDocument931 pages2016 EdBookvarun7189100% (1)

- AJCC Breast Cancer Staging SystemDocument50 pagesAJCC Breast Cancer Staging SystemLucan MihaelaNo ratings yet

- The Diversity of Gastric Carcinoma PDFDocument352 pagesThe Diversity of Gastric Carcinoma PDFFrozinschi Eduarth PaulNo ratings yet

- Eva M. Wojcik, Daniel F.I. Kurtycz, Dorothy L. Rosenthal - The Paris System For Reporting Urinary Cytology-Springer (2022)Document340 pagesEva M. Wojcik, Daniel F.I. Kurtycz, Dorothy L. Rosenthal - The Paris System For Reporting Urinary Cytology-Springer (2022)learta100% (2)

- Blue Book PDFDocument126 pagesBlue Book PDFgojo_11No ratings yet

- EAU Pocket Guidelines 2019Document438 pagesEAU Pocket Guidelines 2019Gourab kundu100% (1)

- Cellular AberrationDocument53 pagesCellular AberrationJmBautistaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Lecture RespiratoryDocument13 pagesNursing Lecture RespiratoryAedge010100% (1)

- Breast Cancer 1Document49 pagesBreast Cancer 1rahmatia alimunNo ratings yet

- Imaging Breast Ca Nipple DischargeDocument1 pageImaging Breast Ca Nipple DischargesjulurisNo ratings yet

- Updates in The Eighth Edition of The Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging Classification For Urologic CancersDocument10 pagesUpdates in The Eighth Edition of The Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging Classification For Urologic CancersAbhishek PandeyNo ratings yet

- Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma of Salivary GlandsDocument16 pagesAdenoid Cystic Carcinoma of Salivary GlandsVinoster ProductionNo ratings yet